Abstract

Objectives. We systematically reviewed the literature on the impact of returning to work on health among working-aged adults.

Methods. We searched 6 electronic databases in 2005. We selected longitudinal studies that documented a transition from unemployment to employment and included a comparison group. Two reviewers independently appraised the retrieved literature for potential relevance and methodological quality.

Results. Eighteen studies met our inclusion criteria, including 1 randomized controlled trial. Fifteen studies revealed a beneficial effect of returning to work on health, either demonstrating a significant improvement in health after reemployment or a significant decline in health attributed to continued unemployment. We also found evidence for health selection, suggesting that poor health interferes with people’s ability to go back to work. Some evidence suggested that earlier reemployment may be associated with better health.

Conclusions. Beneficial health effects of returning to work have been documented in a variety of populations, times, and settings. Return-to-work programs may improve not only financial situations but also health.

The negative effects of unemployment on health have been well documented.1–5 Several longitudinal studies have shown a relationship between unemployment and mortality.6–11 The population health consequences arising from periods of economic decline have engendered some controversy,12 but the evidence on the association between unemployment and poor health is sufficiently robust to suggest causality.13,14 However, most studies examine the detrimental effects of negative social experiences rather than the constructive effects of positive events. As a result, research into the relationship between employment status and health has predominantly focused on the effects of job loss and unemployment rather than on the health impact of returning to work.

The question of whether social factors are a cause or consequence of disease and illness is often framed in the context of the debate over social selection versus social causation and remains a source of controversy.15–19 The social causation hypothesis suggests that employment leads to health benefits, and the social selection hypothesis proposes that health is a necessary condition for employment. Research suggests that the causation effect may be of greater importance than the selection effect, but both mechanisms may interact and reinforce each other.15,18 We conducted a systematic review of the research literature on the impact of returning to work on physical and mental health in working-aged adults.

METHODS

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, EBM Reviews, CINAHL, and HEALTHSTAR for publications through 2005. We developed our search strategy through consultation with a librarian (detailed search strategy is provided in Appendix A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). We did not impose any restrictions on earliest date of publication or language in the search strategy.

Inclusion Criteria

Participants.

Study participants were working-aged adult men, women, or both (aged ≥ 25 years). We excluded studies that reported the employment transitions of younger adults or recent graduates (e.g., school leavers) because we were interested in documenting the experiences of those who were returning to work after a period of unemployment. The realities of those who return to work are sufficiently different from those who are entering the labor market for the first time to warrant distinct attention.20

Assessments.

The studies evaluated participants’ movement from unemployment to employment, including (but not limited to) reporting on any program or policy designed to promote or support the process of returning to work for individuals or groups. We defined returning to work as the transition from unemployment to employment, whether full-time, part-time, sheltered, unstable, or contract work.

Outcome measures.

Studies provided measures for how employment affected the physical or mental health of the study population, whether self-reported or more objective measures of health. Studies also had to measure health outcomes for the return-to-work group and the comparison group(s). Finally, we included studies that reported health outcomes at all measurement times or only at the last measurement time.

Study designs.

We considered for inclusion controlled studies (e.g., randomized controlled trials and quasi-experimental studies), cohort studies, and case–control studies that documented a transition from unemployment to employment and included a comparison group. We excluded ecological studies (where the unit of analysis was not the individual) and cross-sectional studies (which lacked several data collection points over time). Studies measured employment status at least twice for all participants and incorporated a group of participants who underwent a change in employment status from unemployed at baseline to employed at a subsequent time (the return-to-work group) and a comparison group with participants who remained unemployed (the continuously unemployed group), employed (the continuously employed group), or experienced job loss (the job loss group) during the course of the study.

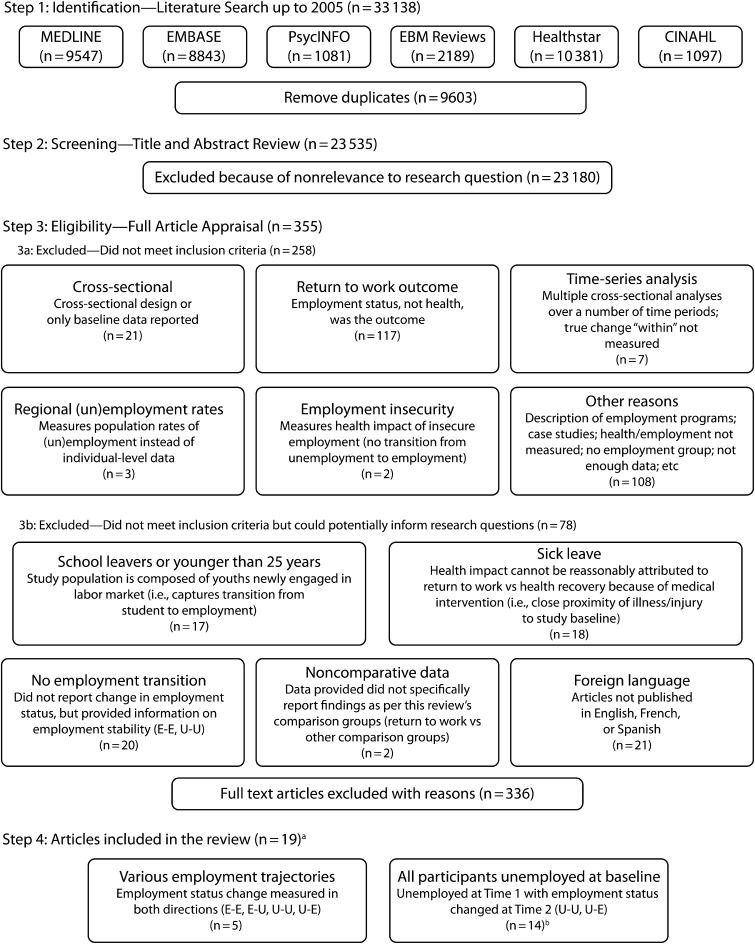

Two reviewers independently assessed the title and abstracts identified from the searches for potential relevance according to the selection criteria. We then retrieved the full text for all potentially relevant studies, which were again assessed independently by 2 reviewers, who used a standardized form that outlined the specific selection criteria (Appendix B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). All disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by consensus. During each of these reviewing stages, we did not exclude studies because of language of publication until the data extraction or full article appraisal phase, at which time we were only able to fully review studies that were written in English, French, or Spanish (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Search strategy for literature review on association between returning to work and health among working-aged adults.

aThe 19 articles represent 18 studies.

bThe 14 articles represent 13 studies.

Methodological Quality

Two independent reviewers appraised methodological quality with a modified version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies (Appendix C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).21 The purpose of this appraisal was not to exclude studies according to a predetermined cutoff, but to discuss the overall quality of the available studies and to help inform the analysis, conclusions, and recommendations of the review.

The quality criteria were (1) sample selection—representativeness of the exposed cohort (e.g., random selection), representativeness of the nonexposed cohort (i.e., drawn from the same community as the exposed cohort), and independent confirmation of exposure; (2) comparability—study controlled for age, gender, and baseline health; and (3) outcomes—assessment (e.g., blind assessment, record linkage), length of follow-up of at least 1 year, and adequacy of follow-up (≥ 80% of participants responding at the end of the study).

We removed question 4 from the original scale (demonstration that the outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study) because the question was intended to assess the quality of studies that incorporate binary outcomes (e.g., disease incidence). The need to determine that the outcome of interest was absent at the start of the study is an important consideration of quality if the aim of the study is to determine whether the outcome developed over time. However, most of the studies in our review measured subjective health by continuous variables, so it was expected that some degree of the outcome of interest was measured, and thus present, at the start of the study.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted by 1 reviewer and checked independently for accuracy by 2 additional reviewers. When we identified missing data, we attempted to contact authors to obtain the information. Reviewers discussed disagreements until we reached consensus.

We also examined several study features to identify any recurring characteristics that might be associated with better health outcomes. This semiqualitative approach has been used to identify the relationship between study characteristics and outcomes.22 We examined whether the outcomes could be related to various study characteristics, such as whether the study evaluated an employment intervention or not, the type of health outcome (physical versus mental health), the population targeted (general versus specific subset), and the type of market economy associated with the country where the study took place (liberal versus coordinated). Our aim was to find out whether a positive association between returning to work and health was more likely to take place, for example, in countries with different types of market economies.23 We also examined whether the studies explicitly evaluated the relative contribution of causation and selection.

RESULTS

We identified 33 138 citations in our database searches; 355 articles met the criteria for full appraisal. We excluded 336 articles after full review because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). From these, we identified 78 articles as potentially informative to the background and context of our review despite not being eligible for analysis: 17 articles were excluded because all participants were youths entering the labor market for the first time (i.e., recent graduates or younger than 25 years), thus capturing the transition from school to employment24–40; 18 articles were excluded because they reported the health consequences of returning to work after sick leave, so that the health effects evaluated could not reasonably be attributed to returning to work as opposed to a medical intervention41–58; 20 articles were excluded because they did not report change in employment status but might provide information on employment stability4,9,59–76; 2 articles were excluded because the data reported did not compare return to work to other comparison groups as required by our inclusion criteria77,78; and 21 articles were excluded because they were written in languages other than English, French, or Spanish (references available on request).

Study Characteristics

Eighteen studies reported in 19 articles met the criteria for inclusion8,20,79–95 (Table 1; Appendix D, a longer version of this table, is available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Two articles were included as 1 study because both articles reported data from the same sample of participants (1 article presented additional follow-up data to the previous article).83,84 Studies were heterogeneous in populations, interventions, comparison groups, outcomes, and length of follow-up. Accordingly, we did not attempt to pool the results in a meta-analysis.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of Studies in Literature Review on Association Between Returning to Work and Health Among Working-Aged Adults

| Study | Research Focus | Study Design (Location) | Sample | Intervention | Comparison Groups |

| Beiser et al.79 | Employment status and depression | Prospective cohort (Vancouver, BC, Canada) | Probability sample of adult refugees (≥ 18 y) from Southeast Asia | NA | Unemployed–employedUnemployed–unemployedEmployed–employedEmployed–unemployed |

| Bond et al.80 | Work experiences, nonvocational outcomes, and severe mental illness | Prospective cohort (Southwest Washington, DC) | Convenience sample of unemployed individuals who were clients from case management agency serving people with severe mental illness | Individual employment placement and support (control group received traditional vocational rehab services) | Unemployed–unemployedUnemployed–minimal workaUnemployed–sheltered workbUnemployed–competitive workc |

| Breslin and Mustard20 | Unemployment and mental health | Retrospective cohort (Canada) | Multistaged, stratified, random sampling of respondents to the National Population Health Survey from the general population aged 31–55 y to select a representative sample of households across Canada | NA | Employed–unemployedUnemployed–unemployedUnemployed–employed |

| Bromberger and Matthews81 | Changes in employment status and depressive symptomatology in middle-aged women | Prospective cohort (Allegheny County, PA) | Random sample by zip code and driver’s license registry of middle-aged women. | NA | Employed–employedUnemployed–unemployedEmployed–unemployedUnemployed–employed |

| Caplan et al.82 | Inability to obtain reemployment and depression/other negative affective states | Prospective cohort. Data from vocational rehabilitation randomized controlled trial. (Southeastern Michigan) | Convenience sample of a broad spectrum of unemployed persons registering at 4 state employment compensation offices | Eight 3-h sessions over 2 wk in job seeking with problem-solving, inoculation against setbacks, and positive social reinforcement(control group received 2.5-page booklet of job-seeking tips) | Unemployed–unemployedUnemployed–employeddeUnemployed–unemployed–unemployedUnemployed–employed–unemployeddeUnemployed–unemployed–employedUnemployed–employed–employedde |

| Claussen83,84,f | Selection and causation among healthy and sick unemployed | Prospective cohort (4 municipalities in Grenland, Norway) | Random sample of registered unemployed persons who were unemployed > 12 wk | NA | Unemployed–unemployedUnemployed–employedUnemployed–< 12 mo workUnemployed–1–4 y workUnemployed–> 4 y work |

| Claussen85,g | Alcohol abuse and unemployment | Prospective cohort (4 municipalities in Grenland, Norway) | Random sample of registered unemployed persons aged 16–63 y who were unemployed > 12 wk | NA | Unemployed–unemployedUnemployed–employed |

| DiClementi et al.86 | Successful vs unsuccessful reemployment among equivalent health statuses | Retrospective double cohort (United States) | Convenience sample of unemployed patients at an HIV/AIDS primary care clinic in a large university-affiliated hospital | Unspecified return-to-work program | Unemployed–employedUnemployed–unemployed |

| Ginexi et al.87 | Reemployment and depressive symptoms/control beliefs | Prospective cohort (Southern Maryland) | Convenience sample of White and African American newly unemployed individuals recruited from 5 state employment agencies | NA | Unemployed–unknownUnemployed–unemployedUnemployed–temporary employment or unemployed–part-timeemployment Unemployed–full-time employment |

| Martikainen and Valkonen8 | Unemployment, reemployment, and mortality during increasing unemployment | Retrospective cohort (Finland) | Census records for all adults aged 25–59 y | NA | Employed–employedUnemployed–unemployedEmployed–unemployedUnemployed–employed |

| Mueser et al.88 | Competitive employment and nonvocational functioning among those with severe mental illness | Prospective cohort. Data from vocational rehabilitation randomized controlled trial (2 New Hampshire cities). | Unemployed persons with severe mental illness aged 20–65 y Sampling strategy not reported | Participants randomly assigned to supported employment or prevocational skills training vocational rehabilitation group | Unemployed–unemployedUnemployed–employed |

| Payne and Jones89 | Reemployment, mental and physical health, and social class | Prospective cohort (United Kingdom) | White, married, unemployed men aged 25–39 y and unemployed 6–11 moSampling strategy not reported | NA) | Unemployed–employedUnemployed–unemployed |

| Schaufeli and VanYperen90 | Negative employment changes and psychological distress | Prospective cohort with external control (Netherlands) | Convenience sample of graduates registered at labor offices who were unemployed ≥ 1 y | NA | Unemployed–employedUnemployed–unemployed |

| Soumerai and Avorn91 | Part-time employment and mental/physical health among aged retirees | Randomized controlled trialParticipants were randomized to work and no-work conditions (Revere, MA) | Convenience sample of applicants to a municipal park maintenance work program, aged ≥ 60 y | Senior Citizen Park Maintenance Corps, a 25-wk half-time park maintenance work/training program | Unemployed–employedUnemployed–unemployed |

| Studnicka et al.92 | Physical health and long-term unemployment | Retrospective cohort (Northeastern Austria) | Convenience sample of former employees of a furniture factory in a small rural town | NA | Unemployed–employedUnemployed–unemployed |

| Thomas et al.93 | Changes in employment status and mental health | Retrospective cohort (United Kingdom) | Participants in household panel survey, aged 16–75 ySampling strategy not reported | NA | Employed–employedUnemployed–unemployedEmployed–unemployedUnemployed–employed |

| Vuori and Vesalainen94 | Labor market intervention affects on unemployed job-seekers | Prospective cohort (Finland) | Convenience sample of job seekers unemployed < 1 y | Participants could take part in ≥ 1 labor market interventions (84.3% participation): a guidance course, 60–100 h in 2 wk; vocational training for 6 mo; and subsidized employment for 6 mo | Unemployed–employedUnemployed–unemployed |

| Warr and Jackson95 | Psychological impact of prolonged unemployment and reemployment | Prospective cohort (Unemployment benefit offices across United Kingdom) | Men registered as unemployed who had held a previous job for 3 mo in semiskilled or unskilled workSampling strategy not clearly defined | NA | Unemployed–unemployedUnemployed–employed |

Note. NA = not applicable.

Paid work in sheltered or competitive employment, but with earnings lower than respective medians.

Paid work licensed by Department of Labor.

Regular community jobs.

Groups combined for analyses.

Reemployed included participants who worked > 20 h and reported working enough.

These 2 articles reported data from the same participants, the 1994 article83 at baseline and the 1999 article84 at follow-up.

Same participants as Clausen's other articles,83,84 but reported separately because outcome and sample attrition rates were different.

Seven studies were conducted in the United States; 3 in the United Kingdom; 2 each in Canada, Norway, and Finland; and 1 each in the Netherlands and Austria. The review samples totaled 2 516 440 participants, with study sample sizes ranging from 54 participants to 2.5 million. Although all studies had adult participants, some focused exclusively on women,81 men,89,95 people living with HIV,86 people diagnosed with mental illness,88 refugees,79 elderly individuals,91 or unemployed adults.80,82–85,87,90,92 The rest studied a sample of the general population.8,20,93,94 Of the 14 studies that reported their sampling strategies, 8 used convenience sampling,80,82,86,87,90–92,94 4 used random sampling,20,81,83–85 and 2 used probability sampling.8,79 Length of follow-up ranged from 4 months to 8 years. The number of data collection points ranged from 2 to 8.

Six studies provided health data in the context of an employment intervention.80,82,86,88,91,94 Various interventions were studied: supportive employment, job-seeking support, return-to-work programs, vocational rehabilitation, and subsidized employment. Although some of these studies evaluated the effects of employment interventions with randomized controlled trial methods, we aggregated the health data according to the employment groups we defined for our review (i.e., return-to-work versus continuously unemployed, continuously employed, or job loss groups) and not according to the groups that were the object of the original randomization (e.g., employment program versus control group). Thus, the randomization schemes of the original studies do not apply to our results because in intervention studies some participants randomized to the employment program may not obtain employment, and some participants assigned to the control group may successfully go back to work. The only exception to this general observation was a study that evaluated the health effects of returning to work directly by randomizing participants to work and no work conditions.91 To our knowledge, this is the only randomized controlled trial to directly evaluate returning to work as an active intervention for achieving better health. Thus, for the purposes of our review, all included studies used a longitudinal cohort design (12 prospective and 5 retrospective cohort studies), and 1 study was a randomized controlled trial.91

For comparison groups, 13 studies presented data from inception cohorts of unemployed participants, providing comparative data on participants who remained unemployed and those who returned to work,80,82–92,94,95 and 5 studies reported data for a variety of employment trajectories (returning to work, job loss, continuously unemployed, or continuously employed).8,20,79,81,93

Eight of the studies met the criterion for the representativeness of the exposed cohort because they used random selection rather than convenience sampling in their selection of participants for the return-to-work group (Table 2). Only 2 studies met the criterion for ascertainment of exposure by ensuring an independent confirmation of exposure (e.g., employment records from government agencies). Fourteen studies compared their cohorts by baseline health; only 10 studies compared cohorts by age and gender. Four of the studies met the criterion for objective assessment of outcome, by using either physician diagnoses or mortality data from a record linkage. Fourteen studies sustained follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur (≥ 1 year); only 7 studies retained more than 80% of participants at follow-up, offering limited assurance that the attrition rate was unlikely to introduce bias.

TABLE 2—

Quality Appraisal Studies Included in Literature Review on Association Between Returning to Work and Health Among Working-Aged Adults

| Selection |

Comparison |

Outcome |

||||||

| Study | Random Selection of Exposed Cohort; No Convenience Sample | Nonexposed Cohort Drawn From Same Community | Independent Confirmation of Exposure | Age and Gender | Baseline Health | Blind assessment or record linkage | Follow-Up ³ 1 y | End of Follow-Up Had ³ 80% Participant Rate |

| Beiser et al.79 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Bond et al.80 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Not Specified |

| Breslin and Mustard20 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Bromberger and Matthews81 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Caplan et al.82 | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Claussen83,84,a | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Claussen85,b | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| DiClementi et al.86 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not Specified |

| Ginexi et al.87 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Martikainen and Valkonen8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mueser et al.88 | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Payne and Jones89 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Schaufeli and VanYperen90 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Soumerai and Avorn91 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Studnicka et al.92 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Thomas et al.93 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Not Specified |

| Vuori and Vesalainen94 | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Warr and Jackson95 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

Note. We used a modified version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Assessment Scale for Cohort Studies.

These 2 articles reported data from the same participants, the 1994 article83 at 2-year follow-up and the 1999 article84 at 5-year follow-up.

Same participants as Clausen's other articles,83,84 but reported separately because outcome and sample attrition rates were different.

Health Outcomes

Fifteen studies observed a beneficial effect of returning to work on health, shown by either a significant improvement in health after reemployment or a significant decline in health attributed to unemployment8,79–85,87–89,91–95 (Table 3; Appendix E, a longer version of this table, is available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Only 3 studies failed to find a beneficial health effect of returning to work,20,86,90 and none found a harmful effect associated with returning to work.

TABLE 3—

Study Outcomes in Literature Review on Association Between Returning to Work and Health Among Working-Aged Adults

| Study | Sample Size at Each Data Collection Point, No. (% completed) | Follow-up (Data Collection Points, No.). | Health Outcomes (Confounders) | Main Findings |

| Beiser et al.79,a | Baseline: 1348Follow-up: 1169 (87) | 2 y (2) | Depressive affect (Baseline depression score, education, gender, age, baseline and follow-up marital status) | With all other factors controlled, the consistently employed had significantly lower depression scores at follow-up than the consistently unemployed or people who lost their jobs between baseline and follow-up, but not lower than the previously unemployed who found jobs by follow-up |

| Starting a job between baseline and follow-up was accompanied by lowered depression scores | ||||

| Refugees employed at baseline who went on to lose their job had higher initial depression levels than the initially employed who kept on working | ||||

| Bond et al.80,a | Baseline: 149Follow-up 1: 149 (100)Final follow-up: 149 (100) | 1.5 y (4) | Psychiatric symptoms [BPRS score total] (Group assignment [IPS versus control], months of paid employment in past 5 y, Global Assessment Scale days in hospital in past year) | Clients with severe mental illness who worked in competitive employment for an extended period showed a greater rate of improvement in several nonvocational outcomes (including overall BPRS); statistical differences partially attributable to deterioration in minimal work and nonworking groups |

| Competitive group unchanged on the BPRS total from baseline to 18 mo; nonworking group deteriorated substantially | ||||

| Breslin and Mustard20,b | Baseline: 6096Final follow-up: 6096 (100) | 2 y (2) | Distress, depression (Gender, marital status, education, unusual life events, chronic medical condition) | Adults aged 31–55 y who became unemployed more likely to report elevated distress at follow-up 1 than those who remained employed; review analyses of cases of clinical depression showed similar but somewhat weaker association (causation for job loss, not return-to-work effect) |

| High distress increased risk of not finding work; review analysis found that unemployment predicted distress and distress predicted employment status, supporting selection hypothesis | ||||

| Review analyses did not show increased distress at follow-up among those unemployed at both time points, suggesting adaptation to unemployment | ||||

| Bromberger and Matthews81,a | Baseline: 541Final follow-up: 524 (97) | 3 y (2) | Depression [BDI] (Education, marital status) | Depressive symptoms decreased among newly employed and increased for others |

| New employment appeared to have acute positive effect on mood | ||||

| Caplan et al.82,a | Baseline: 928Follow-up 1: 693 (75)Final follow-up: 628 (68) | 4 mo (3) | Depression, anxiety, quality of life (Baseline scores for dependent variables) | People who found reemployment scored significantly lower on anxiety, depression, and anger and higher on self-esteem and quality of life than persons who remained unemployed |

| Claussen83,84,ac | Baseline: 310Follow-up 1: 291 (94)Final follow-up: 210 (68) | 2 y835 y84 (3) | Somatic symptoms, anxiety, depression, psychiatric syndrome personality disorder, hormones [cortisol, testosterone, prolactine], immunoglobins (Education, years in paid work, duration of longest-lasting job, gender, socioeconomic status, social network, health measures at baseline) | At 5-y follow-up, considerable recovery after reemployment, supporting causation hypothesis84Results differed from 2-y follow-up, when selection was remarkable and recovery after reemployment was fairly small83Psychiatric syndrome diagnosis at baseline (1988) reduced odds of having job in 1993; 43% of changes occurred in participants without a diagnosis |

| Claussen85,ad | Baseline: 310Follow-up 1: 291 (93.9)Final follow-up: 228 (73.5) | 5 y (3) | Alcohol dependency (Gender, age, education, socioeconomic status, social network, employment, commitment, AUDIT case for alcohol dependency at baseline) | Obtaining job significantly reduced chances of scoring positive on AUDIT questionnaire from 1988 to 1993 to 34% of odds for still-unemployed persons; calculating continuous AUDIT scores in linear regression with continuous covariates gave same result (P = .02); recovery likely same as deterioration after job loss |

| Selection mechanism probably not major cause of high prevalence of alcohol problems in unemployed populations | ||||

| DiClementi et al.86,b | Unemployed–employed:baseline: 135Final follow-up: 135 (100)Unemployed–unemployed:Baseline: 135Final follow-up: 135 (100) | 5 y (2) | Mental illness [other than substance abuse, psychiatric diagnoses, injection drug use] | Return-to-work group had significantly more psychiatric diagnoses other than substance abuse than matched control group; control group had significantly more diagnoses related to injection and other drug use, possibly because accessing mental health services was entry point into the return-to-work program, and substance abuse may be associated with avoidance or inability to access mental health treatmente |

| Ginexi et al.87,a | Baseline: 254Follow-up 1: 228 (90)Final follow-up: 214 (84) | 11 mo (3) | Depression (Gender, minority status, age, SES) | Reemployed job seekers showed significantly steeper linear reduction in symptoms (dropping an average of 4.55 points faster over the year). |

| Reemployment within 6 mo predicted declines in average and individual levels of depressive symptoms, implying that early reemployment was related to resolution of depressive symptoms | ||||

| Pattern did not hold for reemployment obtained after 6 mo; job seekers who still unemployed at follow-up 1 had higher, stable level of depressive symptoms throughout study | ||||

| Depressive symptoms failed to predict time to any reemployment or time to permanent full-time reemployment | ||||

| Martikainen and Valkonen8,a | Baseline: 2.5 millionFinal follow-up: 2.5 million (100) | 5 y (3) | Mortality (Age, education, occupational class, marital status) | Jobless persons who were reemployed had higher mortality than those who were continuously employed, lower than those who remained unemployed, after controls for confounders |

| Excess mortality of unemployed persons during times of low national unemployment greater than during recession | ||||

| Association between unemployment and mortality weakened as general unemployment rate increased | ||||

| Mueser et al.88,a | Baseline: 143Final follow-up: 133 (93) | 1.5 y (4) | Psychiatric symptoms (Gender, diagnosis, vocational group) | Persons working at follow-up tended to have fewer symptoms (particularly thought disorder and affect on the BPRS), higher Global Assessment scores, better self-esteem, and more satisfaction with finances and vocational services than did unemployed persons. Employment was associated with better functioning in a range of nonvocational domains, even after control for baseline functioning, suggesting benefit of rehabilitation program |

| Results may reflect combined effects of less symptomatic patients finding jobs more easily and benefits of work for functioning, although neither hypothesis alone was directly supported by data | ||||

| Payne and Jones89,a | Baseline: 399Follow-up 1: 286 (71.7)Final follow-up: 144 (36.1)f | 2 y (3) | General psychological distress, anxiety, depression (Not reported) | Perceived psychological symptoms improved, regardless of occupational status, after reemployment |

| Schaufeli and VanYperen90,b | Baseline: 467Final follow-up: 317 (64.1) | 2 y (4) | Psychological distress (Gender) | General tendency toward better psychological health observed in both reemployed and continuously long-term unemployed groups; long-term unemployed reached plateau health, then adapted |

| Less distressed long-term unemployed technical college graduates were more likely than more distressed to become reemployed, supporting selection hypothesis | ||||

| Soumerai and Avorn91,a | Baseline: 54Final follow-up: 47 (87%)g | 6 mo (2) | Perceived health status (Not reported) | Strongest effect of employment program at completion was on perceived health: 8% of intervention participants reported health as fair, 36% as excellent; 45% of control participants had fair and 14% had excellent health |

| Results similar for perceived changes in health over the previous 6 mo | ||||

| Although most respondents in both groups perceived no change health, improvements in health were far more common in intervention participants, and health declines more common in control participants; differences were statistically highly significant | ||||

| Studnicka et al.92,a | Baseline: 172Final follow-up: 172 (100)Unemployed–employed: 106Unemployed–unemployed: 66 | 1 y (2) | Psychological health, physical health in past year (Age, gender, previous level of employment, physical health, previous unemployment) | Persons unemployed 12 mo were 8 times as likely as the reemployed to report poor psychological health (OR = 8.5; 95% CI = 4.2, 17.0)Self-reported physical ill health likely attributable largely to former work (56% of all disorders were related by respondents to former work history) and to be associated with current employment status (OR = 5.6; 95% CI = 2.7, 11.5) |

| Unemployed overused health services (OR = 2.2;95% CI = 1.2, 4.1); this differential was greater for older and sicker persons | ||||

| Thomas et al.93,a | Baseline: 5092Final follow-up: 5092 (100) | 8 y (8) | Psychological distress [GHQ score ³ ≥ 3] (Age, gender, long-term sickness, previous GHQ case) | For both men and women, transitions from paid employment to either unemployment or long term illness were associated with poor mental health |

| Transitions from unemployment into paid employment were associated with good mental health | ||||

| Effects of transitions on mental health strongest in first 6 mo | ||||

| People with considerable psychological distress during unemployment were less likely to become employed, supporting selection hypothesis | ||||

| Vuori and Vesalainen94,a | Baseline: 559Final follow-up: 401 (71.7) | 1 y (2) | Psychological distress [GHQ] (Baseline job seeking activity, baseline psychological distress, baseline financial situation, follow-up 1 financial situation, type of intervention) | Participants who were unemployed at both measurement times reported no change in amount of distress symptoms over timeReemployed and unemployed persons at follow-up 1 did not differ in baseline distress symptoms (t(374) = 0.01; NS), failing to support selection hypothesis |

| At follow-up 1, reemployed persons reported significantly fewer symptoms than did unemployed (t(375) = 3.83; P < .001) | ||||

| Warr and Jackson95,a | Baseline: 954Follow-up 1: 629 (66) | 9 mo (2) | Psychological ill health [GHQ], general Health change, physical health change, psychological health change (None) | Gaining (and maintaining) a job significantly improved psychological health and reported health and reduced financial strain |

Note. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Ratings Scale; CI = confidence interval GHQ = General Health Questionnaire; NS = not signficant; OR = odds ratio; SES = socioeconomic status.

Study showed a beneficial health effect of returning to work.

Study showed no health effect of returning to work.

Articles reported data from the same participants, the 1994 article83 at 2-year follow-up and the 1999 article84 at 5-year follow-up.

Same participants as Clausen's other articles,83,84 but reported separately because outcome and sample attrition rates were different.

Return-to-work group received diagnoses from mental health team; matched control participants received substance use disorder diagnoses during medical examinations, emergency room visits, and incarceration, not from study mental health team.

Only participants who were unemployed at baseline and follow-up 1 were reinterviewed at final follow-up.

For experimental group, attrition = 100%; for control group, attrition = 76%.

Eleven studies explicitly examined the relative contributions of selection and causation by looking at the direction of the relationship between employment and health. Even though by definition all studies in our review examined the causation hypothesis (i.e., they all evaluated the impact of returning to work on health), these studies tried to elucidate within the same study whether poor health interfered with the prospect of reemployment (selection) or returning to work resulted in improved health status (causation). Four studies found support for the causation hypothesis exclusively85,87,94,95; 5 studies found support for both hypotheses, with a predominant role for the causation hypothesis8,79,83,84,88,93; and 2 studies found support for the selection hypothesis exclusively (Table 4).20,90 Because most studies reported a beneficial effect associated with returning to work, we were unable to determine whether going back to work was associated with better health according to population (general versus specific), health outcome (physical versus mental health), market economy (liberal versus coordinated), or employment intervention (evaluated or not).

TABLE 4—

Study Features in Literature Review on Association Between Returning to Work and Health Among Working-Aged Adults

| Support for Hypothesesa |

Outcomes |

Population |

Market Economy |

||||||

| Study Finding | Selection | Causation | Vocational Intervention | Physical Health | Mental Health | General | Specific | Liberal | Coordinated |

| Positive effect | |||||||||

| Beiser et al.79 | Yes | Yes | No | Depressive symtoms | Refugees | Canada | |||

| Bond et al.80 | Yes | Psychiatric symptoms | Severely mentally ill persons | United States | |||||

| Bromberger and Matthews81 | No | Depression | Women | United States | |||||

| Caplan et al.82 | Yes | Depression, anxiety | Yes | United States | |||||

| Claussen83,84,b | Yes | Yes | No | Somatic symptoms | Depression, anxiety | Yes | Norway | ||

| Claussen85,c | No | Yes | No | Alcohol | Yes | Norway | |||

| Ginexi et al.87 | No | Yes | No | Depression | Yes | United States | |||

| Martikainen and Valkonen8 | Yes | Yes | No | Mortality | Yes | Finland | |||

| Mueser et al.88 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Psychiatric symptoms | Severely mentally ill persons | United States | |||

| Payne and Jones89 | No | Depression, anxiety | Yes | United Kingdom | |||||

| Soumerai and Avorn91 | Yesd | Health status | Elderly | United States | |||||

| Studnicka et al.92 | Yes | Physical health | Psychological health | Yes | Austria | ||||

| Thomas et al.93 | Yes | Yes | No | Psychological distress | Yes | United Kingdom | |||

| Vuori and Vesalainen94 | No | Yes | Yes | Psychological distress | Yes | Finland | |||

| Warr and Jackson95 | No | Yes | No | General health | Psychological health | Yes | United Kingdom | ||

| No effect | |||||||||

| Breslin and Mustard20 | Yes | Noe | No | Distress, depression | Yes | Canada | |||

| DiClementi et al.86 | Yes | Substance use, psychiatric diagnosis | HIV-positive persons | United States | |||||

| Schaufeli and VanYperen90 | Yes | No | No | Psychological distress | Yes | Netherlands | |||

| Feature prevalence, no./total (%) | 7/18 (39) | 9/18 (50) | 7/18 (39) | 5/18 (28) | 16/18 (89) | 12/18 (67) | 6/18 (33) | 12/18 (67) | 6/18 (33) |

| Success rate with feature, no./total (%) | 5/7 (71) | 9/9 (100) | 6/7 (86) | 5/5 (100) | 13/16 (81) | 10/12 (83) | 5/6 (83) | 10/12 (83) | 5/6 (83) |

| Success rate without feature, no./total (%) | 10/11 (91) | 6/9 (67) | 9/11 (82) | 10//13 (77) | 2/2 (100) | 5/6 (83) | 10/12 (83) | 5/6 (83) | 10/12 (83) |

| Rate difference, % | –20 | 33 | 4 | 23 | –19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

From studies that explicitly examined the contribution of both causation and selection hypotheses.

Results differed from 2-y follow-up, when selection was remarkable and recovery after reemployment was fairly small.83

Same participants as Clausen's other articles,83,84 but reported separately because outcome and sample attrition rates were different.

Work itself.

Causation supported for job loss but not for returning to work.

DISCUSSION

Our systematic review found support for a beneficial health effect of returning to work. Most of the longitudinal studies we reviewed found a positive association between returning to work and health outcomes in a variety of populations, at different times, and in different settings. We also found evidence to support health selection, although to a lesser extent, suggesting that poor health also interferes with people’s prospects of returning to work. Taken together, these studies suggest that selection and causation mechanisms are mutually reinforcing processes that work synergistically to shape people’s employment and health trajectories over time.

Explanatory Hypotheses

Causation.

Of the studies that exclusively found support for the hypothesis that returning to work results in better health, one found that reemployment reversed the negative effect of unemployment on mental health and, conversely, that depressive symptoms failed to predict reemployment status later.87 Another study suggested that the high prevalence of heavy drinking among the unemployed was mostly explained by unemployment preceding heavy drinking rather than alcohol abuse causing unemployment.85 In a third study, participants who returned to work reported less psychological distress than did those who remained unemployed, and participants who were unable to find employment reported no change in distress over time.94

Another study likewise found no changes in psychological distress for participants who remained unemployed, but the distress scores for those who returned to work were reduced almost by half at follow-up.95 This study found that the constraints of a difficult job market, lengthier unemployment, and older age were more important predictors of reemployment status than poor health. Authors of some of these studies, however, acknowledged that it was difficult to rule out the possibility that poor health may have delayed reemployment.

Selection.

Two studies found exclusive support for the hypothesis that healthy job seekers are more attractive to employers or more likely to survive the challenges of job hunts than are unhealthy unemployed persons.20,90 One study showed no increase in psychological distress at follow-up for participants who were continuously unemployed,20 and the other found that the continuously unemployed exhibited a tendency toward improved psychological health over time.90 These findings suggest that adaptation to unemployment may be a reason for the predominant role of the selection effect in these studies. Findings from one study suggested that adaptation to unemployment sets in after 2 years of unemployment.90

Relative contribution of causation and selection.

The other studies that examined both the selection and causation hypotheses generally found that these processes were mutually reinforcing, although causation appeared to play a more prominent role. Interestingly, authors of one study suggested that their findings supporting the beneficial effect of returning to work on health may reflect a worsening of psychiatric symptoms in the continuously unemployed group rather than an improvement in successful job hunters.80 This was interpreted to be a partially reassuring finding, however, because of concerns raised in the mental health literature about the potential negative effects of increased levels of stress related to work in people with severe mental illness. In this case, even though returning to work was not associated with improved symptoms, at least it was not harmful to health, unlike continuous unemployment. Another study found that participants who lost their jobs were more depressed than those who kept them, but suggested that rather than impeding the chances of finding a job, poor mental health may make it more difficult to stay employed.79

Other Influences of Unemployment and Reemployment

Possible reversal of the negative health effects of unemployment.

Related to the causation–selection debate is the practical question of whether returning to work completely reverses the negative effect of job loss on health. After the job loss experience, going back to work may provide workers with complete or partial recovery to baseline health. Longitudinal studies would need to follow the same people over consecutive employment transitions to address this question directly. Although we were unable to find such a study, 4 studies cast some indirect light on this issue.8,79,81,93 These studies compared different employment groups reflecting different employment trajectories (returning to work, job loss, continuously unemployed); typically the continuously employed group was the reference category. A study that used census data to examine the effects of employment transitions on mortality found that mortality rates among participants who returned to work were higher than among those who remained employed but lower than for those who lost their jobs or remained unemployed.8 This suggests that going back to work may provide only a partial recovery from the job loss experience. Another study found a similar pattern, reporting that the return-to-work group had more psychological distress than the continuously employed group but less than both the job loss and the continuously unemployed groups.93

Another study, however, found that depression scores were similar among the continuously employed and the reemployed, but the continuously employed had lower scores than those who lost their jobs or remained unemployed. This suggests that returning to work may provide a complete recovery from the job loss experience.79 In a different study, only the return-to-work group experienced reductions in depression scores resulting in follow-up scores similar to the continuously employed group81; however, this study was of lesser quality than the other 3 studies that allowed the examination of this question.8,79,93

Time to reemployment.

Another practical question is whether time to reemployment matters to health. Ginexi et al. found that those who returned to work within 6 months of becoming unemployed had more pronounced declines in depressive symptoms than those who went back to work after a longer period.87 This suggests that early reemployment is more conducive than a later return to work to resolving depressive symptoms resulting from job loss and raises the possibility that there may be a window of time during which returning to work has a positive effect on health. This same study also observed that the longer it took to find a job, the more difficult it became to find one.87 More than half the sample had still not found a full-time job a year after becoming unemployed. This high incidence of unemployment after an extended period was also reported by other studies.83,84

Another study also found that the health effects of any employment transition were stronger within 6 months of the change in employment status (including the return-to-work transition, but not exclusively).93 If these findings can be replicated in other studies, it suggests that employment programs should be offered to unemployed people as soon as possible after job loss, not only to preserve the capacity for reemployment but also for health reasons.

Potential mechanisms for the health benefits of returning to work.

Potential mechanisms of action were investigated by only a few studies; this limited our ability to reach conclusions about the underlying reasons for the health benefits of returning to work. One study found that the association between unemployment and health tends to weaken as the general unemployment rate increases, suggesting that the experience of unemployment during a recession is less harmful to health than during less uncertain times.8 This may be attributable to the reduced stigma or stress associated with unemployment when others are in the same situation. Complementing this finding, another study suggested that selection effects may be more pronounced in times of economic uncertainty because an increase in unemployment rates may force people to go back to insecure jobs, and thus the health benefits of returning to work may be attenuated.84 Other studies examined the potential mediating role of financial strain79 and psychosocial stress.81

Limitations

The end date in our search for articles was 2005, and we were unable to analyze articles published in languages other than English, French, or Spanish. Although our search strategy captured many articles, we may have missed relevant studies because we did not conduct hand searches of specific journals or perform searches of the gray literature. As is the case with many systematic reviews, we were unable to pool the data for meta-analysis because of significant heterogeneity in many study features.

We were unable to evaluate the relative contribution of various study features to the relationship between returning to work and health because most of the included studies reported beneficial effects associated with returning to work. We did not ascertain the underlying reasons for the beneficial effects of returning to work on health because few studies examined potential mechanisms of action.

We did not find any studies that examined the effectiveness of policy interventions or system-level improvements to the provision of disability income or benefits. We found only a few studies that evaluated interventions intended to improve reemployment rates that also took health outcomes into account. However, Audhoe et al. recently reviewed studies that report on the effect of vocational rehabilitation on reemployment and mental distress.96

Conclusions

Our systematic review found evidence to support the health benefits of returning to work in a variety of populations, times, and settings, suggesting that a portion of the relationship is causal. We also found support for selection effects, with poor health interfering with people’s prospects of returning to work or remaining employed. In addition, we found some evidence to suggest that earlier reemployment (< 6 months since job loss) may be associated with better health outcomes than is delayed reemployment. We were unable to determine whether returning to work provided partial or complete reversal of the negative health effects associated with job loss.

We detected a moderate association between returning to work and health, at least to the extent that the associations reported in these longitudinal studies remained significant after adjustment for potential confounders. A majority of the studies controlled for baseline health, which suggests that reasonable attempts were made at minimizing the potential effect of health selection. However, fewer than half of the studies controlled for age and gender at the same time; these essential variables may act as confounders in the relationship between employment and health. This highlights the inconsistency in controls for important confounders in the literature.

It is still unclear from current research whether the health effects of returning to work are moderated or mediated by gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or other sociobehavioral factors, such as workplace discrimination in the case of stigmatizing disease conditions (e.g., depression or HIV/AIDS). In addition, the circumstances surrounding the job loss experience have not yet been properly described. Future research should take into account whether the spell of unemployment preceding the return to work was voluntary or was caused by illness, layoff, redundancy, or termination with cause. The reasons for separation from the labor market may confer different psychological or physical effects, and thus they may also have a differential impact on health associated with going back to work. Conversely, the type of job and location associated with returning to work (whether people return to the same job or a different one) may moderate the association between returning to work and health.

We found only 1 experimental study, conducted almost 20 years ago, that demonstrated the beneficial effect of returning to work on health. Randomized intervention studies are needed to explore the effects of paid employment on health. Further studies should also focus on elucidating the mechanisms behind the reported positive relationship between returning to work and health.

Acknowledgments

In-kind administrative support was provided by the Ontario HIV Treatment Network.

We acknowledge David Lightfoot for his assistance in developing the search strategy, and Sarah Tumaliuan, Rachael Walisser, Indira Fernando, Oliver Sun, Sarah Carrie, Jesmin Antony, and Peter Lugomirsky for assisting with screening and data extraction.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review approval was not required because the data were obtained from secondary sources.

References

- 1.Gallo WT, Teng HM, Falba TA, Kasl SV, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH. The impact of late career job loss on myocardial infarction and stroke: a 10 year follow up using the health and retirement survey. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63(10):683–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strully KW. Job loss and health in the US labor market. Demography. 2009;46(2):221–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasl SV, Rodriguez E, Lasch KE. The impact of unemployment on health and well-being. : Dohrenwend BPE, Adversity, Stress, and Psychopathology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998:111–131 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallo WT, Bradley EH, Siegel M, Kasl SV. Health effects of involuntary job loss among older workers: findings from the Health and Retirement Survey. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55(3):S131–S140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartley M. Unemployment and ill health: understanding the relationship. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1994;48(4):333–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sullivan D, von Wachter T. Job displacement and mortality: an analysis using administrative data. Q J Econ. 2009;124(3):1265–1306 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martikainen PT. Unemployment and mortality among Finnish men, 1981–5. BMJ. 1990;301(6749):407–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martikainen PT, Valkonen T. Excess mortality of unemployed men and women during a period of rapidly increasing unemployment. Lancet. 1996;348(9032):909–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris JK, Cook DG, Shaper AG. Loss of employment and mortality. BMJ. 1994;308(6937):1135–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sorlie PD, Rogot E. Mortality by employment status in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):983–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stefansson CG. Long-term unemployment and mortality in Sweden, 1980–1986. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(4):419–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catalano R, Goldman-Mellor S, Saxton Ket al. The health effects of economic decline. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:431–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin RL, Shah CP, Svoboda TJ. The impact of unemployment on health: a review of the evidence. J Public Health Policy. 1997;18(3):275–301 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58(5):295–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blane D, Smith GD, Bartley M. Social selection: What does it contribute to social class differences in health? Sociol Health Illn. 1993;15(1):1–15 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartley M. Unemployment and health: selection or causation—a false antithesis? Sociol Health Illn. 1988;10(1):41–67 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adda J, Chandola T, Marmot M. Socio-economic status and health: causality and pathways. J Econom. 2003;112(1):57–63 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Does employment affect health? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(3):230–243 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wade TJ, Pevalin DJ. Marital transitions and mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45(2):155–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breslin FC, Mustard C. Factors influencing the impact of unemployment on mental health among young and older adults in a longitudinal, population-based survey. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2003;29(1):5–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell Det al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. 2008. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm. Accessed June 1, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330(7494):765–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall P, Soskice D. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banks MH, Jackson PR. Unemployment and risk of minor psychiatric disorder in young people: cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence. Psychol Med. 1982;12(4):789–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feather NT, O’Brien GE. A longitudinal analysis of the effects of different patterns of employment and unemployment on school-leavers. Br J Psychol. 1986;77(4):459–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. The effects of unemployment on psychiatric illness during young adulthood. Psychol Med. 1997;27(2):371–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graetz B. Health consequences of employment and unemployment: longitudinal evidence for young men and women. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(6):715–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammarström A. Health consequences of youth unemployment. Public Health. 1994;108(6):403–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammarström A, Janlert U. Early unemployment can contribute to adult health problems: results from a longitudinal study of school leavers. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(8):624–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammarström A, Janlert U, Theorell T. Youth unemployment and ill health: results from a 2-year follow-up study. Soc Sci Med. 1988;26(10):1025–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hammer T. Unemployment and mental health among young people: a longitudinal study. J Adolesc. 1993;16(4):407–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morrell S, Taylor R, Quine S, Kerr C, Western J. A cohort study of unemployment as a cause of psychological disturbance in Australian youth. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(11):1553–1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrell S, Taylor R, Quine S, Kerr C, Western J. A case–control study of employment status and mortality in a cohort of Australian youth. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(3):383–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meân Patterson LJ. Long-term unemployment amongst adolescents: a longitudinal study. J Adolesc. 1997;20(3):261–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prause JA, Dooley D. Effect of underemployment on school-leavers’ self-esteem. J Adolesc. 1997;20(3):243–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaufeli WB. Youth unemployment and mental health: some Dutch findings. J Adolesc. 1997;20(3):281–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winefield AH, Tiggemann M. Affective reactions to employment and unemployment as a function of prior expectations and motivation. Psychol Rep. 1994;75(1 Pt 1):243–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winefield AH, Tiggemann M, Goldney RD. Psychological concomitants of satisfactory employment and unemployment in young people. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1988;23(3):149–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winefield AH, Tiggemann M, Winefield HR. The psychological impact of unemployment and unsatisfactory employment in young men and women: longitudinal and cross-sectional data. Br J Psychol. 1991;82(4):473–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winefield HR, Winefield AH, Tiggemann M, Smith S. Unemployment, drug use, and health in late adolescence. Psychother Psychosom. 1987;47(3–4):204–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abbas AE, Brodie B, Stone Get al. Frequency of returning to work one and six months following percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94(11):1403–1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boudrez H, De Backer G. Recent findings on return to work after an acute myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass grafting. Acta Cardiol. 2000;55(6):341–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dawson DR, Levine B, Schwartz ML, Stuss DT. Acute predictors of real-world outcomes following traumatic brain injury: a prospective study. Brain Inj. 2004;18(3):221–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gard G, Gille KA, Grahn B. Functional activities and psychosocial factors in the rehabilitation of patients with low back pain. Scand J Caring Sci. 2000;14(2):75–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joy JM, Lowy J, Mansoor JK. Increased pain tolerance as an indicator of return to work in low-back injuries after work hardening. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55(2):200–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lötters F, Hogg-Johnson S, Burdorf A. Health status, its perceptions, and effect on return to work and recurrent sick leave. Spine. 2005;30(9):1086–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McLain RF. Functional outcomes after surgery for spinal fractures: return to work and activity. Spine. 2004;29(4):470–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moeri R, Balague F, Carron R, van Melle G. Lombalgies chroniques et reinsertion professionnelle: facteurs pronostiques [Chronic back pain and professional rehabilitation: prognostic factors]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1991;121(50):1897–1899 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nandi A, Galea S, Tracy Met al. Job loss, unemployment, work stress, job satisfaction, and the persistence of posttraumatic stress disorder one year after the September 11 attacks. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46(10):1057–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rao N, Rosenthal M, Cronin-Stubbs D, Lambert R, Barnes P, Swanson B. Return to work after rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 1990;4(1):49–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roquebrune JP, Cottez JL, Baudouy M. Reprise du travail apres infarctus du myocarde [Return to work after myocardial infarction]. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris). 1981;30(2):121–124 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Romito P, Ancel PY, Lelong N. Unemployment and psychological distress one year after childbirth in France. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54(3):185–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schönherr MC, Groothoff JW, Mulder GA, Eisma WH. Participation and satisfaction after spinal cord injury: results of a vocational and leisure outcome study. Spinal Cord. 2005;43(4):241–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stansfeld SA, Fuhrer R, Head J, Ferrie J, Shipley M. Work and psychiatric disorder in the Whitehall II study. J Psychosom Res. 1997;43(1):73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strand LI, Ljunggren AE, Haldorsen EM, Espehaug B. The impact of physical function and pain on work status at 1-year follow-up in patients with back pain. Spine. 2001;26(7):800–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sykes DH, Hanley M, Boyle DM, Higginson JDS. Work strain and the post-discharge adjustment of patients following a heart attack. Psychol Health. 2000;15(5):609–623 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vestling M, Tufvesson B, Iwarsson S. Indicators for return to work after stroke and the importance of work for subjective well-being and life satisfaction. J Rehabil Med. 2003;35(3):127–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kauderer-Hubel M, Buchwalsky R. Aspekte der beruflichen Wiedereingliederung nach Herzinfarkt in Abhangigkeit vom Schweregrad der Erkrankung—Nachbefragung von Patienten mit Anschlussheilbehandlung.[Aspects of vocational reintegration following myocardial infarct in relation to disease severity–follow-up of patients with after-care treatment]. Rehabilitation. 1986;25(1):9–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alexander CS, Markowitz R. Maternal employment and use of pediatric clinic services. Med Care. 1986;24(2):134–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brenner SO, Levi L. Long-term unemployment among women in Sweden. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25(2):153–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clingerman E, Stuifbergen A, Becker H. The influence of resources on perceived functional limitations among women with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2004;36(6):312–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Daltroy LH, Iversen MD, Larson MGet al. A controlled trial of an educational program to prevent low back injuries. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(5):322–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dooley D, Catalano R, Wilson G. Depression and unemployment: panel findings from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Am J Community Psychol. 1994;22(6):745–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dunham MD, Multon KD, Koller JR. A comparison of adult learning disability subtypes in the vocational rehabilitation system. Rehabil Psychol. 1999;44(3):248–265 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ferrie JE, Martikainen P, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG, Stansfeld SA, Smith GD. Employment status and health after privatisation in white collar civil servants: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2001;322(7287):647–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Montgomery SM, Cook DG, Bartley MJ, Wadsworth MEJ. Unemployment, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and body weight in young British men. Eur J Public Health. 1998;8(1):21–27 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Montgomery SM, Cook DG, Bartley MJ, Wadsworth MEJ. Unemployment pre-dates symptoms of depression and anxiety resulting in medical consultation in young men. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(1):95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morris JK, Cook DG, Shaper AG. Non-employment and changes in smoking, drinking, and body weight. BMJ. 1992;304(6826):536–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pelicier Y. Psychopathologic problems related to unemployment. [Problèmes psychopathologiques liés au chômage.] Presse Therm Clim. 1984;121(4):193–195 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Philippe A. Suicide et chômage. [Suicide and unemployment.] Psychol Med (Paris). 1988;20(3):380–382 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reine I, Novo M, Hammarström A. Does the association between ill health and unemployment differ between young people and adults? Results from a 14-year follow-up study with a focus on psychological health and smoking. Public Health. 2004;118(5):337–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sacker A, Wiggins RD, Bartley M, McDonough P. Self-rated health trajectories in the United States and the United Kingdom: a comparative study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(5):812–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Samele C, van Os J, McKenzie Ket al. Does socioeconomic status predict course and outcome in patients with psychosis? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36(12):573–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sasseville M, Grunberg F. Chômage et santé mentale. [Unemployment and mental health.] Can J Psychiatry. 1987; 32(9):798–802 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wehman PH, Revell WG, Kregel J, Kreutzer JS, Callahan M, Banks PD. Supported employment: an alternative model for vocational rehabilitation of persons with severe neurologic, psychiatric, or physical disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72(2):101–105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Whyte AS, Carroll LJ. A preliminary examination of the relationship between employment, pain and disability in an amputee population. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(9):462–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Frese M, Mohr G. Prolonged unemployment and depression in older workers: a longitudinal study of intervening variables. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25(2):173–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hamilton VL, Hoffman WS, Broman CL, Rauma D. Unemployment, distress, and coping: a panel study of autoworkers. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65(2):234–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Beiser M, Johnson PJ, Turner RJ. Unemployment, underemployment and depressive affect among Southeast Asian refugees. Psychol Med. 1993;23(3):731–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bond GR, Resnick SG, Drake RE, Xie H, McHugo GJ, Bebout RR. Does competitive employment improve nonvocational outcomes for people with severe mental illness? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(3):489–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bromberger JT, Matthews KA. Employment status and depressive symptoms in middle-aged women: a longitudinal investigation. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(2):202–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Caplan RD, Vinokur AD, Price RH, van Ryn M. Job seeking, reemployment, and mental health: a randomized field experiment in coping with job loss. J Appl Psychol. 1989;74(5):759–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Claussen B. Psychologically and biochemically assessed stress in a follow-up study of long-term unemployed. Work Stress. 1994;8(1):4–18 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Claussen B. Health and re-employment in a five-year follow-up of long-term unemployed. Scand J Public Health. 1999;27(2):94–100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Claussen B. Alcohol disorders and re-employment in a 5-year follow-up of long-term unemployed. Addiction. 1999;94(1):133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.DiClementi JD, Ross MK, Mallo C, Johnson SC. Predictors of successful return to work from HIV-related disability. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2004;3(3):89–96 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ginexi EM, Howe GW, Caplan RD. Depression and control beliefs in relation to reemployment: what are the directions of effect? J Occup Health Psychol. 2000;5(3):323–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mueser KT, Becker DR, Torrey WCet al. Work and nonvocational domains of functioning in persons with severe mental illness: a longitudinal analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185(7):419–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Payne R, Jones JG. Social class and re-employment: changes in health and perceived financial circumstances. J Occup Behav. 1987;8(2):175–184 [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schaufeli WB, VanYperen NW. Unemployment and psychological distress among graduates: a longitudinal study. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1992;65(4):291–305 [Google Scholar]

- 91.Soumerai SB, Avorn J. Perceived health, life satisfaction, and activity in urban elderly: a controlled study of the impact of part-time work. J Gerontol. 1983;38(3):356–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Studnicka M, Studnicka-Benke A, Wogerbauer Get al. Psychological health, self-reported physical health and health service use. Risk differential observed after one year of unemployment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1991;26(2):86–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Thomas C, Benzeval M, Stansfeld SA. Employment transitions and mental health: an analysis from the British household panel survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(3):243–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vuori J, Vesalainen J. Labour market interventions as predictors of re-employment, job seeking activity and psychological distress among the unemployed. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1999;72(4):523–538 [Google Scholar]

- 95.Warr P, Jackson P. Factors influencing the psychological impact of prolonged unemployment and of re-employment. Psychol Med. 1985;15(4):795–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Audhoe SS, Hoving JL, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH. Vocational interventions for unemployed: effects on work participation and mental distress. A systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(1):1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]