Abstract

The largest mucosal surface in the body is in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, a location that is heavily colonized by normally harmless microbes. A key mechanism required for maintaining a homeostatic balance between this microbial burden and the lymphocytes that densely populate the GI tract is the production and trans-epithelial transport of poly-reactive IgA1. Within the mucosal tissues, B cells respond to cytokines, sometimes in the absence of T cell help, undergo class switch recombination (CSR) of their Immunoglobulin (Ig) receptor to IgA, and differentiate to become plasma cells (PC)2. However, IgA-secreting PC likely have additional attributes that are needed for coping with the tremendous bacterial load in the GI tract. Here we report that IgA+ PC also produce the anti-microbial mediators TNFα and iNOS, and express many molecules that are commonly associated with monocyte/granulocytic cell types. The development of iNOS-producing IgA+ PC can be recapitulated in vitro in the presence of gut stroma, and the acquisition of this multi-functional phenotype in vivo and in vitro relies on microbial co-stimulation. Deletion of TNFα and iNOS in B-lineage cells resulted in a reduction in IgA production, altered diversification of the gut microbiota and poor clearance of a gut-tropic pathogen. These findings reveal a novel adaptation to maintaining homeostasis in the gut, and extend the repertoire of protective responses exhibited by some B lineage cells.

The majority of class switch recombination (CSR) to IgA takes place in the Peyer’s Patches (PP), and requires encounters between B cells and cytokine-secreting T cells within germinal centers. However, IgA CSR can also take place outside of PP within isolated lymphoid follicles (ILF) of the lamina propria (LP)2. Local production of nitric oxide (NO) via the inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2 or iNOS) has been shown to be a critical mediator of CSR to IgA within the small intestinal LP of mice3,4. Since Lymphotoxin (LT)-deficient mice have a significant, unexplained IgA defect5, we hypothesized that this could be due to a lack of iNOS in the gut. Indeed, we identified a population of CD11clowiNOS+ cells by flow cytometric analysis of intestinal LP cell preparations, and these CD11cloiNOS+ cells were decreased in both LTβ−/− and LTβR−/− mice (Fig. 1a and Table I), confirming a relationship between iNOS and the generation/maintenance of IgA+ PC4.

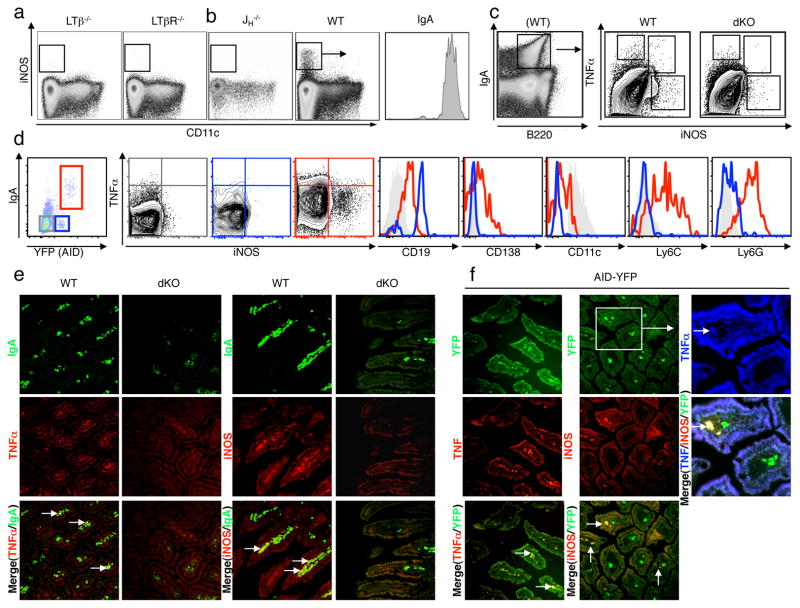

Figure 1. IgA+ plasma cells in the small intestinal lamina propria can produce iNOS and TNFα.

a,b, Small intestinal lamina propria cells (LPC) from LTβ−/− and LTβR−/−, JH−/− and WT mice were isolated and viable cells were analyzed for CD11c and iNOS expression by flow cytometry. Please see quantification in Supplemental Table I. iNOS+ cells were gated and analysed for IgA expression. c, Small intestinal LPC cells were isolated from WT and TNFα−/−iNOS−/− double-deficient (dKO) mice and analysed for IgA, TNFα and iNOS expression (note a WT example here for IgA/B220 staining is shown. Although IgA-expressing cells are reduced in dKO mice as per Fig. 3c, it is possible to still gate on IgA-expressing cells within the LP of dKO mice). Frequencies of TNFα+ and iNOS+ populations can be found in Suppl. Table II. d, Intestinal LPC from AID-YFP animals were isolated and viable cells were analyzed for their expression of IgA and YFP. Specifically, YFP−IgA− = grey rectangle, YFP+IgA− = blue rectangle and YFP+IgA+ = red rectangle, please see Suppl. Table III for relative frequency of each population. These gated populations were further analyzed for their expression of iNOS and TNFα (note that cross-hairs were added based on isotype control staining; see Suppl. Table IV for average frequencies of each population). Expression of other lineage-specific markers for each of the three populations are denoted as histograms (YFP−IgA− = grey trace, YFP+IgA− = blue trace, YFP+IgA+ = red trace). Note that for CD11c expression, YFP−IgA− dendritic cells were used as a positive control (grey trace). Representative plots are shown from n=9 mice. Sections of small intestines from WT versus dKO mice (e) and AID+YFP+ mice (f) were stained with specific fluorochrome-tagged antibodies for iNOS, TNFα and IgA (or visualized for YFP) as indicated. Stained sections were then analyzed by fluorescence microscopy at 200x. Representative pictures are shown from at least 3 separate experiments. Arrows denote areas of co-localization and the rectangle indicates a villus that was enlarged to visualize simultaneous expression of each iNOS, TNFα and YFP.

Table I.

| Frequency of iNOS+ CD11clo cells | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| WT (n=20) | LTβ−/− (n=6) | LTβR−/− (n=6) | JH−/− (n=6) | dKO (n=5) | |

| % iNOS+CD11clo Mean (SEM)& | 0.50** (0.05) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.008 (0.00) | 0.03 (0.03) |

All values indicate Mean and (SEM) and represent at least 3 different experiments. Frequency of iNOS+CD11clo from total live lymphocytes.

Significant difference when WT is compared with the other four groups, p<0.005.

The absence of iNOS-expressing cells in LT-deficient mice prompted us to ask whether B-lineage cells could influence the expression of iNOS within the gut, since LT-deficient mice lack some B cell subsets in the small intestinal lamina propria5. Accordingly, we examined B-cell deficient mice for evidence of iNOS expression in the gut and found that CD11cloiNOS+ cells were completely absent in JH−/− mice, Rag2−/− mice, and strongly reduced in μMt mice (Fig. 1b, Suppl. Table I and Suppl. Fig. 1a). Since LT-deficient mice also lack IgA+ PC, and iNOS-expressing cells are strongly reduced in B-cell deficient and LT-deficient mice, we examined the possibility that IgA+ PC may have the capacity to produce iNOS. Indeed, when we gated on iNOS+ cells, we found that they expressed IgA (Fig. 1a) and low levels of B220 (not shown), suggesting that IgA-producing cells may account for significant iNOS-expression within the gut in the steady state. In agreement with this data, we found that purified CD11cloiNOS+ cells exhibited evidence of a rearranged V-D-JH4 product (Suppl. Fig. 1b).

We next asked what proportion of IgA+ cells express iNOS. Compared to knock-out controls, a subset of IgA+ PC express iNOS and Tumor Necrosis Factor α (TNFα), the expression of which has also been described in monocyte-derived cells6 (see Fig. 1c, Suppl. Table II for relative frequencies of each population and Fig. 1e for immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy). We further confirmed these observations by performing cytospins on small intestinal LP-derived cells (Suppl. Fig. 2–3). Collectively, these data suggest that gut-resident B-lineage cells contribute towards iNOS and TNFα expression within the small intestinal LP.

To better determine which B-lineage cells were expressing TNFα/iNOS, we examined whether prior expression of Activation Induced cytidine Deaminase (AID), an enzyme that is required for both CSR and somatic hypermutation (SHM) in B cells7, correlated with iNOS and TNFα expression. Using AID-cre x YFP mice8, we observed three populations of cells in the small intestinal LP: (1) YFP−IgA− cells = any LP derived cell that have not undergone CSR nor SHM, such as a DC or a naïve B cells, (2) YFP+IgA− cells = B cells that have undertaken SHM or have undergone CSR to a class of Ig other than IgA and (3) YFP+IgA+ cells = B cells that have undergone CSR to IgA (Fig. 1d and Suppl. Table III for relative frequencies of each population). Confirming that YFP+IgA+ cells likely represent IgA+ PC, YFP+IgA+ cells also expressed low levels of the plasma cell marker Syndecan-1 (CD138) and were CD19low (compare YFP+IgA+ (red trace) with YFP+IgA− B cells (blue trace) which are CD138−CD19hi, Fig. 1d). Using this approach, we found that some YFP+IgA+ cells (red box) expressed iNOS as well as TNFα (Fig. 1d and Suppl. Table IV for the relative expression of TNFα/iNOS for each population). Furthermore, YFP+IgA+ cells also expressed leukocyte surface markers commonly associated with monocytic and granulocytic cells, including Ly6C and Ly6G9 and low levels of CD11c (Fig. 1d, for CD11c, DC (grey trace) were used as a comparator). By IF microscopy, we found that YFP expression co-localizes with IgA expression as expected (Suppl. Fig. 4), and using these AID-YFP tissues we detected the expression of iNOS and TNFα in some, but not all YFP+ cells in the small intestinal LP tissue (Fig. 1f), and occasional co-expression of both iNOS and TNFα was observed in YFP+ cells, consistent with our flow cytometry data (Fig. 1f- see boxed insert). Taken together, we have found that a proportion of IgA+ cells within the small intestinal LP express anti-microbial mediators TNFα and iNOS. While we do not detect significant expression of these molecules in other LP cells (YFP+IgA− B cells, YFP− populations), it is possible that our detection methods are not sufficiently sensitive to pick-up low-levels of protein expression of TNFα and iNOS in these cell types, or that expression of TNFα and iNOS in these cells is induced during particular microbial encounters as has been observed in non-mucosal tissues6.

Interestingly, not all IgA+ cells expressed iNOS or TNFα, or co-expressed both iNOS and TNFα simultaneously (Fig. 1c,d and Suppl. Tables II and IV), which would make sense given the pro-inflammatory nature of these molecules. Indeed, cytospin analysis of IgA+ cells that express iNOS and/or TNFα revealed a different morphology and cellular IgA localization than IgA+iNOS−TNFα− cells, suggesting that acquisition of iNOS and TNFα expression may be accompanied by additional activation steps beyond IgA CSR (Suppl. Fig. 2–3). To further understand the necessary signals required for the induction of these two anti-microbial mediators in IgA+ PC, we assessed the expression of iNOS by IgA+ PC in germ-free (GF) mice. Although greatly reduced in number, IgA+ cells in the LP of GF mice did not express iNOS, however the expression of iNOS could be recovered if GF mice were reconstituted with a limited microbiota (Fig. 2a). Even “reversible colonization” of GF mice with a single species of E. coli (HA107)10 was sufficient to restore iNOS expression in IgA+ cells. Therefore, microbial colonization of the gut is necessary for the expression of iNOS by IgA+ PC, and a single species of bacteria is sufficient.

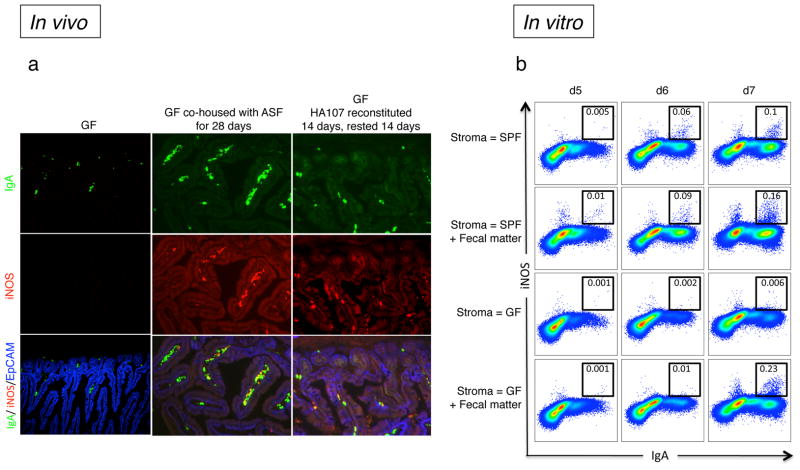

Figure 2. TNFα and iNOS-expression in IgA+ plasma cells requires microbial exposure.

a, Sections of small intestines of germ-free (GF) and GF mice that were re-colonized with either a defined Altered Schaedler Flora (ASF), or reversibly re-colonized with HA107 E. coli by continual gavage administration for 14 days followed by 14 days without gavage returning them to a GF status10. All sections were stained with specific fluorochrome-tagged antibodies for IgA (green), iNOS (red) and EpCAM (blue) and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Representative pictures are shown from 6 mice per group. b, B220+ bone marrow (BM) cells from CD45.1+ wild type mice were co-cultured for 7 days with CD45.2+ intestinal lamina propria cells (referred to as gut stroma) from either SPF or GF animals in the presence of IL-7, TGFβ, IL-21 and αCD40 antibody. In some cases faecal matter (intestinal wash) was added on the first day of the culture. The expression of IgA and iNOS was analyzed by flow cytometry, and the black boxes that indicate cells that are considered iNOS+ were based on the absence of staining derived from isotype controls (not shown). To ensure selective analysis of BM-derived precursors, cells were pre-gated on the CD45.2− population. Representative flow cytometry plots of cells are depicted. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments with 3–4 mice per group per experiment.

To recapitulate what we observed in vivo, we assessed whether the acquisition of iNOS expression in IgA+ cells could be supported by gut-derived support/stromal cells (see Materials and Methods where we describe the generation of stromal cell monolayers) compared with a bone marrow (BM)-derived S17 stromal cell line or ex vivo preparations of BM stroma11. In the presence of a combination of pro-IgA CSR factors, both BM and gut stroma could support the development of YFP+IgA+ cells from B220+ BM cells derived from AID-YFP mice. However, only gut stroma, but not S17 or BM-derived stroma was able to support the development of iNOS+IgA+ cells (Suppl. Fig. 5a,b). Interestingly, gut stroma from LTβR−/− mice was likewise able to support the development of iNOS+IgA+ cells in the presence of pro-IgA CSR factors, suggesting that the defective CSR observed in LTβR−/− mice can be overcome in vitro in the presence of exogenous cytokines and CD40 ligation (Suppl. Fig. 5b). Not unlike the in vivo scenario, microbes are required for in vitro development of iNOS+IgA+ cells since preparations of gut stroma from SPF but not GF mice supports the development of iNOS+IgA+ cells (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, co-incubation of GF gut stroma with fecal matter derived from SPF mice restores the development of iNOS+IgA+ cells (Fig. 2b). Thus, our in vivo and in vitro results suggest that the gut microenvironment, influenced by the local microbiota, supports the development of multi-functional B cells that express IgA and iNOS.

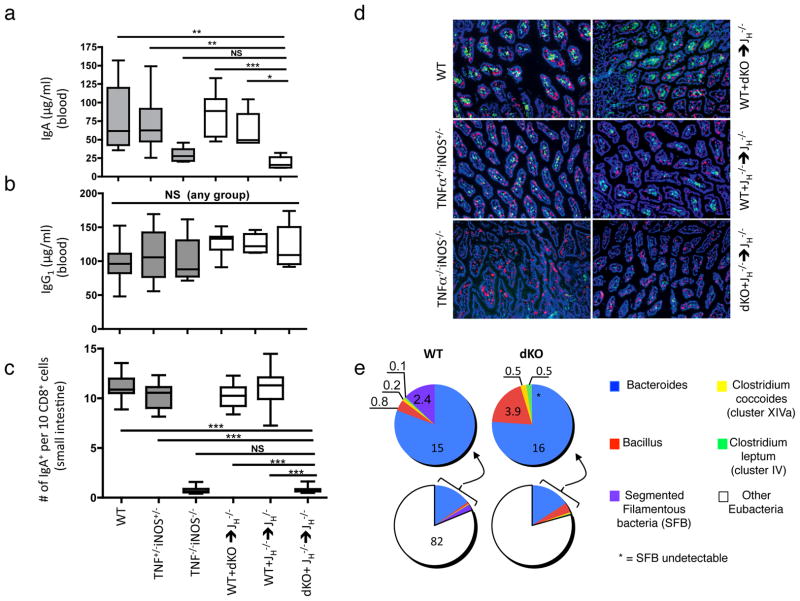

To examine the functional relevance of TNFα/iNOS expression in IgA+ cells, we created TNFα/iNOS double knockout (dKO) mice. TNFα/iNOS dKO mice exhibited reduced serum IgA (Fig. 3a), and this reduction was more dramatic than what we observed for iNOS−/− single knockout mice, which, in agreement with previous findings4, also exhibited decreased serum IgA (data not shown). BM from dKO mice, in combination with B-cell deficient JH−/− BM, was used to reconstitute B-cell deficient, lethally irradiated recipients, thus creating mixed BM chimeras in which B cells are unable to produce TNF α/iNOS (see Suppl. Fig. 6). JH −/− + dKO mixed chimeric mice exhibited a normal complement of immune cells in the periphery, although some changes in splenic microarchitecture were noted (Suppl. Fig. 7), in agreement with the effects of B-cell derived TNFα on splenic stromal cell biology12. Consistent with a role for TNFα/iNOS in the regulation of CSR to IgA4, JH−/− + dKO mixed BM chimeric mice exhibited a significant drop in serum IgA but not IgG1 when compared with two groups of control mixed BM chimeric mice (dKO + WT and JH−/− + WT mixed BM chimeric mice) (Fig. 3a–b), and this decrease in serum IgA tracked with significant reductions in IgA+ cells within the LP as quantified by IF microscopy (Fig. 3c–d). Although all mixed BM recipients were generated using the same cohort of recipient mice, we observed changes in the composition of the commensal bacterial community in the small intestine of JH−/− + WT versus JH−/− + dKO reconstituted mixed BM chimeric mice (Fig. 3e). Focusing on microbial populations that are known to influence immune cell function13, we noted that segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) were nearly absent from JH−/− + DKO mixed BM chimeras in small intestinal tissue (p<0.05), as well as in small intestinal “scrapes” enriched for epithelial cells (not shown). In contrast, Clostridium leptum and Bacillus were increased in small intestinal tissue of JH−/− + dKO mixed chimeras, and this may possibly account for the reduced frequency of SFB. The altered composition of commensal microbiota likely reflects the deficiency in TNFα/iNOS rather than a reduction in IgA since mice that are completely IgA-deficient exhibit excessive outgrowth of SFB14. Therefore, although our data do not eliminate the possibility that complete deletion of TNFα/iNOS in all monocytes/DC would impact IgA production, these results show that the expression of TNFα/iNOS in B-lineage cells is essential for the homeostatic production of IgA and the maintenance of an appropriate representation of different commensal microbes within the small intestine.

Figure 3. Reduced IgA production and altered commensal flora composition in iNOS/TNFα double-deficient mixed chimeric mice.

a–b, Steady-state serum IgA, but not IgG1 levels are markedly decreased in dKO and dKO mixed chimeras. Serum IgA and IgG1 levels were measured by ELISA in WT (n = 15) TNF+/−iNOS+/− (n = 12) and TNF−/−iNOS−/− (dKO, n = 7) non-chimeric mice as well as in WT + dKO (n = 8), JH−/− + WT (n = 5) and JH−/− + dKO (n = 6) mixed chimeric mice. Similar results were obtained with two additional batches of mixed bone marrow chimeric mice (not shown). Data represent means and SD values. c, The numbers of small intestinal LP IgA+ plasma cells and CD8α+ cells were quantified from IF microscopy images utilizing ImageJ. d, Representative images of frozen small intestinal tissue sections derived from the groups described in (a–c) stained for CD8α (red) and IgA (green) and DAPI (blue). A total of 5 different sections from 6 mice per group were analyzed. e, Seven weeks after BM reconstitution, the small intestines of WT and dKO mixed chimeras (n = 4) were analyzed for their commensal bacteria composition by quantitative real-time PCR amplification of 16S rRNA isolated from small intestinal preparations. Colored pie graphs represent the percentages of the indicated bacteria species. A significant difference in the relative representation of segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) was observed between WT and dKO mice. Similar results for SFB were obtained in small intestinal “scrapes” of the epithelium (data not shown). Data represent means and SD values. *** p = 0.001, ** p = 0.01, * p < 0.05.

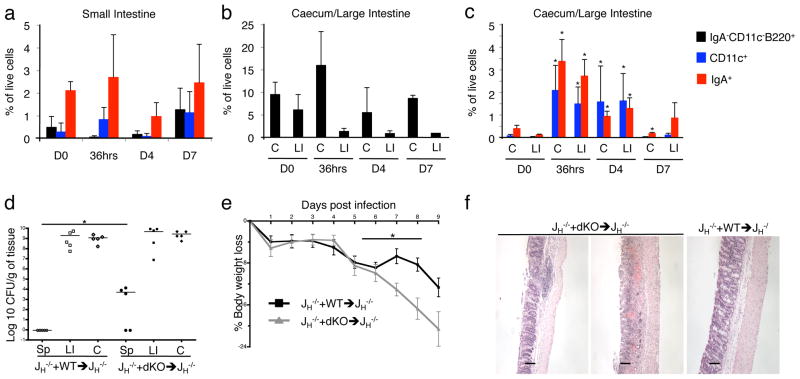

We next assessed the impact of TNFα/iNOS deletion in B cells on clearance of the mouse pathogen Citrobacter rodentium, which colonizes the caecum and large intestine (L.I.) following infection. First, using AID-YFP mice, we found that C. rodentium infection results in a significant accumulation of YFP+IgA+ cells as well as YFP−CD11c+ cells (but not IgA− B cells) in the caecum and L.I. as early as 36 hours post-infection (Fig. 4a–c). With these kinetics established, we infected JH−/− + WT versus JH−/− + dKO mixed BM chimeras with C. rodentium. Interestingly, C. rodentium translocation to the spleen, enhanced weight loss and colonic pathology were all noted in JH−/− + dKO but not JH−/− + WT mixed chimeric mice (Fig. 4d–f). Similar impaired clearance of C. rodentium was observed in JH−/− + dKO mixed BM chimeric mice when they were directly compared with another control group (WT + dKO mixed bone marrow chimeras – see Suppl. Fig. 8a–c). Since we do not observe an accumulation of IgA− B cells at the site of infection, by inference we conclude that along with other DC-mediated immune mechanisms, TNFα/iNOS production by IgA+ PC is required, either directly or indirectly, for optimal control of C. rodentium in the gut, although it cannot be excluded at this stage that TNFα/iNOS production by other B-lineage cells outside of the gut may have contributed to the observed phenotype. Moreover, we cannot eliminate the possibility that production of TNFα/iNOS by B-lineage cells may have provoked the expression of TNFα/iNOS in monocytes/DC in order to control the infection. Nevertheless, our findings show that B cell-associated TNFα/iNOS production is critical for control of C. rodentium, and this may explain why B cell-deficient mice, but not IgA−/− mice, also fail to control C. rodentium15.

Figure 4. iNOS/TNFα double-deficient mixed chimeras are more susceptible to infection with Citrobacter rodentium.

AID-YFP animals were infected by oral gavage with 1×109 colony-forming units (CFU) of a nalidixic-acid resistant strain of Citrobacter rodentium DBS100. a–c, The kinetics of accumulation of viable YFP+IgA−CD11c−B220+ (black bars), YFP−CD11c+ (blue bars) and YFP+IgA+ (red bars) cells in the small intestine, the caecum (C) and the large intestine (LI) as analyzed by flow cytometry (day 0 (D0), 36 hours (36hrs), day 4 (D4) and day 7 (D7)). The percentages of viable cells as mean values and SD are shown (n = 4). A representative example of two individual experiments is shown. d, The colonization by C. rodentium was determined 9 days after infection by homogenizing spleens (Sp), large intestines (LI) and caecums (C) followed by serial dilution plating on nalidixic acid-containing LB plates and counting of colonies. C. rodentium colonization of spleen (Sp) is significantly enhanced in dKO mice at day 9 post- and at D4 post-infection (data not shown). Data are representative of two individual experiments. e, The percentage of body WT + JH −/− →RAG−/− and dKO + JH −/− →RAG−/− mixed chimeras after C. rodentium weight loss in infection over time is depicted. Significantly increased body weight loss was observed in dKO mice from day 6 to 9 post-infection (n=5–12 per group). NB: dKO + JH−/− mixed chimeric mice were sacrificed 9-days post infection for humane reasons as weight loss exceeded 20% of their original body weight. f, Large intestines (LI) from WT + JH−/− and dKO + JH−/− mixed chimeric mice were harvested 9 days post-infection and the pathological scores were analyzed by standard histological staining procedures using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). LI’s from dKO + JH−/− mice show more severe LI pathology. H&E stainings of two representative dKO mice with a moderate and a more severe condition, as well as one representative WT + JH−/− chimeric mouse are shown. The panel shows the original magnification of 100 x. Scale bars represent 100 mm. * p < 0.05.

The immune system responds differently to antigens encountered systemically as opposed to at mucosal surfaces1. We postulate that in the process of differentiating to become IgA+ PC, the gut environment may have imprinted IgA+ cells with more “monocytic” potential, a phenomenon that has been previously observed in vitro16. Indeed, there is a precedent for B cells to display non-conventional “monocyte/DC” functions in other species17 and in response to TLR ligation18, and B cells have emerged as important effector19 and regulatory cells20 during innate responses to bacterial infection. Furthermore, B cells and monocytes share common precursors during their development21,22, and PC have been recently shown to possess antigen-presenting capacity23. These results document a novel effector mechanism for IgA+ PC, which appears to arise in the unique environment of the gut, and may be critical to mount effective responses to microbial assault.

Methods Summary

A detailed methods section is linked to the online version of this paper and can be found at the end of the text.

Supplementary Material

Table II.

| Frequency of IgA+ iNOS/TNFα+ cells | ||

|---|---|---|

| WT (n=14) | dKO (n=10) | |

| % iNOS+ Mean (SEM) | 1.27 (0.42)* | 0.73 (0.26) |

| % TNFα+ Mean (SEM) | 6.50 (1.51)* | 3.72 (1.09)) |

| % TNFα+iNOS+ | 0.76 (0.17)* | 0.37 (0.13) |

All values indicate Mean and (SEM) and represent at least 3 different experiments. Cells are gated previously on IgA+B220− live cells.

Significant difference when WT is compared with dKO in each condition, p<0.05. IgA + cells represented 14.5% +/− 2.1% of the total lamina propria preparation from the cohort of WT mice.

Table III.

| Frequency of different populations of YFP+ vs YFP− cells (n=14) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| IgA− AID+ | IgA− AID− | IgA+ AID+ | |

| Mean (SEM) | 1.18 (0.19) | 94.96 (0.78) | 1.70 (0.32) |

All values indicate Mean and (SEM) and represent at least 2 different experiments using AID-cre x YFP mice.

Table IV.

| Frequency of IgA+iNOS/TNFα+ cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IgA+ AID+ (n=9) | IgA− AID+ (n=9) | IgA− AID− (n=7) | |

| % iNOS+ Mean (SEM) | 3.37 (0.94)** | 0.31 (0.11) | 0.05 (0.02) |

| % TNF+ Mean (SEM) | 4.55 (0.47)*** | 0.72 (0.41) | 0.008 (0.005) |

| % TNF+iNOS+ | 1.50 (0.68)* | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.004 (0.004) |

All values indicate Mean and (SEM) and represent at least 2 different experiments using AID-cre x YFP mice. Significant difference when IgA+AID+ is compared with the other two groups,

p<0.05,

p<0.005,

p<0.0001.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dionne White in the Faculty of Medicine Flow Cytometry core facility and Dr. Harinder Singh for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Elena Verdu (McMaster University) for providing additional germ free mice at very short notice, and we also thank Cynthia Guidos for numerous Rag2−/− mice for mixed bone marrow chimeras. C.P. is supported by a CIHR operating grant MOP# 9862. R.C. is supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. A.M. is supported by a CIHR operating grant MOP# 89783. J.H.F. acknowledges support by an APART-fellowship of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, McGill start-up funds and a CIHR operating grant MOP#114972. N.S. acknowledges the support of a CIHR Doctoral Award. J.L.G. is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and acknowledges the support of CIHR operating grant MOP# 67157 as well as infrastructure support from the Ontario Research Fund and that Canadian Foundation for Innovation. All authors have reviewed and agree with the content of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper.

Author Information: The authors have no competing financial interests

Author Contributions. J.H.F. generated data in Fig. 1d–f, Fig. 3a–d, Fig. 4d–f, Suppl. Fig. 2–4, 7–8. O.R. contributed data in Fig. 1a–d, 3a–b, 4 and Supplemental Fig. 7–8 and Suppl. Tables I–III. N.S. and C.P. contributed data in Fig. 2b and Suppl. Fig. 6. D.D.M. contributed data in Fig. 1a–b, 2a and Suppl. Fig. 1–3. S.H. contributed data in Fig. 2a. A.M. and M.L. contributed Supplemental Fig. 1b (DM did the sort). R.C. provided AID-YFP mice. I.I. originally suggested that we examine IgA+ PC as putative TNFα/iNOS-producing cells and urged us to do the initial experiments. D.P and S.R contributed data in Fig. 3e and provided critical insights. S.E.G. and S.R helped us set up the Citrobacter rodentium experiments and provided critical insights. A.J.M., S.H. and K.M. provided intestinal tissues from germ free and re-colonized mice. J.G provided gene-deficient mice. J.L.G. wrote the manuscript and obtained funding for the work from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

References

- 1.Hooper LV, Macpherson AJ. Immune adaptations that maintain homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:159–169. doi: 10.1038/nri2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fagarasan S, Kawamoto S, Kanagawa O, Suzuki K. Adaptive immune regulation in the gut: T cell-dependent and T cell-independent IgA synthesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:243–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee MR, Seo GY, Kim YM, Kim PH. iNOS potentiates mouse Ig isotype switching through AID expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tezuka H, et al. Regulation of IgA production by naturally occurring TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells. Nature. 2007;448:929–933. doi: 10.1038/nature06033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang HS, et al. Signaling via LTbetaR on the lamina propria stromal cells of the gut is required for IgA production. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:576–582. doi: 10.1038/ni795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serbina NV, Salazar-Mather TP, Biron CA, Kuziel WA, Pamer EG. TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells mediate innate immune defense against bacterial infection. Immunity. 2003;19:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muramatsu M, et al. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crouch EE, et al. Regulation of AID expression in the immune response. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1145–1156. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serbina NV, Pamer EG. Monocyte emigration from bone marrow during bacterial infection requires signals mediated by chemokine receptor CCR2. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:311–317. doi: 10.1038/ni1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hapfelmeier S, et al. Reversible microbial colonization of germ-free mice reveals the dynamics of IgA immune responses. Science. 2010;328:1705–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1188454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cumano A, Dorshkind K, Gillis S, Paige CJ. The influence of S17 stromal cells and interleukin 7 on B cell development. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:2183–2189. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830201006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tumanov AV, et al. Cellular source and molecular form of TNF specify its distinct functions in organization of secondary lymphoid organs. Blood. 2010;116:3456–3464. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivanov II, Littman DR. Modulation of immune homeostasis by commensal bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki K, et al. Aberrant expansion of segmented filamentous bacteria in IgA-deficient gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1981–1986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307317101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maaser C, et al. Clearance of Citrobacter rodentium requires B cells but not secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA) or IgM antibodies. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3315–3324. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3315-3324.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delogu A, et al. Gene repression by Pax5 in B cells is essential for blood cell homeostasis and is reversed in plasma cells. Immunity. 2006;24:269–281. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, et al. B lymphocytes from early vertebrates have potent phagocytic and microbicidal abilities. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1116–1124. doi: 10.1038/ni1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson BA, 3rd , et al. B-lymphoid cells with attributes of dendritic cells regulate T cells via indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10644–10648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914347107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly-Scumpia KM, et al. B cells enhance early innate immune responses during bacterial sepsis. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1673–1682. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neves P, et al. Signaling via the MyD88 adaptor protein in B cells suppresses protective immunity during Salmonella typhimurium infection. Immunity. 2010;33:777–790. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cumano A, Paige CJ, Iscove NN, Brady G. Bipotential precursors of B cells and macrophages in murine fetal liver. Nature. 1992;356:612–615. doi: 10.1038/356612a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montecino-Rodriguez E, Leathers H, Dorshkind K. Bipotential B-macrophage progenitors are present in adult bone marrow. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:83–88. doi: 10.1038/83210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelletier N, et al. Plasma cells negatively regulate the follicular helper T cell program. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1110–1118. doi: 10.1038/ni.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.