Background: Microtubule-dependent chemotherapeutic drugs cause an irreversible peripheral neuropathy through a calcium-dependent signaling pathway.

Results: The addition of candidate compounds (lithium and ibudilast) inhibits harmful changes to cells caused by microtubule-based chemotherapeutic drugs.

Conclusion: Co-administration of ibudilast or lithium inhibits drug-induced changes in cell function.

Significance: Addition of these protectors may inhibit unnecessary damage caused by chemotherapeutic drugs.

Keywords: Calcium Imaging; Calcium Intracellular Release; Calpain; Cancer Chemoprevention; Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate; Neuronal Calcium Sensor-1; Taxol

Abstract

Peripheral neuropathy is one of the most severe and irreversible side effects caused by treatment from several chemotherapeutic drugs, including paclitaxel (Taxol®) and vincristine. Strategies are needed that inhibit this unwanted side effect without altering the chemotherapeutic action of these drugs. We previously identified two proteins in the cellular pathway that lead to Taxol-induced peripheral neuropathy, neuronal calcium sensor-1 (NCS-1) and calpain. Prolonged treatment with Taxol induces activation of calpain, degradation of NCS-1, and loss of intracellular calcium signaling. This paper has focused on understanding the molecular basis for prevention of peripheral neuropathy by testing the effects of addition of two candidate compounds to the existing chemotherapeutic drug regime: lithium and ibudilast. We found that the co-administration of either lithium or ibudilast to neuroblastoma cells that were treated with Taxol or vincristine inhibited activation of calpain and the reductions in NCS-1 levels and calcium signaling associated with these chemotherapeutic drugs. The ability of Taxol to alter microtubule formation was unchanged by the addition of either candidate compound. These results allow us to suggest that it is possible to prevent the unnecessary and irreversible damage caused by chemotherapeutic drugs while still maintaining therapeutic efficacy. Specifically, the addition of either lithium or ibudilast to existing chemotherapy treatment protocols has the potential to prevent chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

Introduction

Paclitaxel (Taxol) and vincristine are natural products that have potent chemotherapeutic action. Administration of these compounds causes an irreversible peripheral neuropathy in a high percent of patients, especially those administered a high dose of these compounds (1, 2). Although both of these drugs bind to tubulin, they are known to evoke opposite responses to microtubule stability. This difference suggests that the biochemical mechanism underlying peripheral neuropathy is independent of the microtubule changes associated with the chemotherapeutic ability of these drugs. In this way, preventative strategies or interventions against this unwanted side effect without altering the chemotherapeutic action should be possible.

Taxanes, such as Taxol and docetaxel, are a group of chemotherapeutic drugs used for treating a number of types of cancer. Taxol is one of the most effective and commonly used treatment options for patients suffering from breast and ovarian cancer (3, 4). The Taxol mechanism of action was first discovered in 1979 and is believed to work by enhancing the polymerization of tubulin to form stable microtubule polymers and essentially prevents depolymerization (5). Docetaxel has a similar mechanism of action and is believed to be more effective as a treatment for ovarian cancer because it has been found to preferentially accumulate in ovarian cancer cells (6, 7).

Vincristine, another class of chemotherapeutic compounds, is also used to treat a variety of forms of cancer including Hodgkin disease (8). Its chemotherapeutic mechanism of action is believed to stem from its high binding affinity for several neuronal cytoskeletal proteins including β-tubulin, which then inhibits microtubule assembly. Although the disruption of microtubule polymerization caused by administration of vincristine is opposite to the effect of Taxol, which stabilizes microtubules, the administration of either compound is neurotoxic (8). Like Taxol, axonal degeneration has been found in animal models of vincristine (9).

Recently, two proteins have been identified in the biochemical pathway used for Taxol-induced peripheral neuropathy, neuronal calcium sensor-1 (NCS-1)2 and calpain (10–12). NCS-1 is a member of a well known family of calcium-binding proteins possessing a high affinity (100 nm range) (13, 14), and it recently was identified as a Taxol-binding partner (10). NCS-1 contains four EF hand calcium-binding domains of which three functionally bind calcium (14). Addition of NCS-1 enhances intracellular calcium signaling through its interaction with the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R) and modulates the function of the InsP3R in a calcium-dependent manner (15). Interestingly, Taxol increases the interaction between NCS-1 and the InsP3R (11) which enhances intracellular calcium signaling. Treatment with Taxol also activates calpain, a calcium-dependent enzyme, which cleaves a number of substrates, including NCS-1 (11, 16) and the InsP3R (32). This cleavage of NCS-1 results in a decrease in the activity of the InsP3R, resulting in a decrease in the generation of intracellular calcium signals (10, 11, 15, 17). Inhibition of calpain with calpastatin, its endogenous inhibitor, or with small molecule inhibitors, protects NCS-1 levels and intracellular calcium signals in neuroblastoma cells treated with Taxol (12). The ability of small molecule inhibitors of calpain to protect Taxol-treated mice from developing peripheral neuropathy (9) leads to the suggestion that the interactions among Taxol, NCS-1, calpain, and InsP3R are important steps in the mechanism leading to the production of peripheral neuropathy by Taxol and possibly other chemotherapeutic drugs (12).

This paper has focused on the biochemical pathways used in inhibition and prevention of peripheral neuropathy by addition of candidate compounds to the existing chemotherapeutic drug regimen. The hypothesis is that it is possible to protect cells from unnecessary damage and maintain the therapeutic efficacy of Taxol because the cellular pathway for treatment and for injury can be separated. Two candidates were identified: lithium and ibudilast. Lithium is used in the treatment of bipolar disease (15, 18, 19). NCS-1 expression is elevated in bipolar patients (20), a condition that would enhance the activity of the InsP3R activity and increase intracellular calcium signals (12). Addition of lithium did not alter NCS-1 binding to the InsP3R, but did reduce intracellular calcium signals to control levels (12). Because Taxol increased intracellular calcium signaling in a NCS-1-dependent manner (11), we hypothesized that the addition of lithium during chemotherapy with Taxol would have the potential to inhibit the initial Taxol-induced increase in activation of the InsP3R, that results in an eventual decrease in overall calcium signaling after prolonged treatment and prevent pathological intracellular calcium signals in neurons.

Ibudilast has been used in several Asian countries to treat bronchial asthma, cerebrovascular disorders, poststroke dizziness, and ocular allergies (21–23). Administration of ibudilast also reverses Taxol-induced allodynia when given 12 and 19 days after the first Taxol injection in a rat model (22). Although there are questions remaining, the mechanism of action for ibudilast for the conditions listed here is thought to be related to its ability to inhibit phosphodiesterases and macrophage migration inhibitory factor (21). Because ibudilast also regulates various neuronal and glial targets linked to neuropathic pain generation (21), we examined the possibility that co-administering ibudilast with either Taxol or vincristine could also prevent the enhanced calcium signaling associated with chemotherapeutic drugs.

In this paper, we found that the addition of either lithium or ibudilast to neuroblastoma cells treated with Taxol protected both NCS-1 levels as well as intracellular calcium signaling. Vincristine was also found to decrease intracellular calcium signaling, and the presence of either candidate compound was also found to protect the cells. The ability of Taxol to alter microtubule formation was unchanged by the addition of lithium or ibudilast. These results suggest that the addition of either lithium or ibudilast to the existing chemotherapy treatment has the potential to prevent chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

NCS-1 Expression and Purification

NCS-1 was expressed and purified as described previously (12, 16).

Binding to NCS-1 Using Tryptophan Fluorescence

Changes in NCS-1 intrinsic fluorescence at 334 nm after addition of various chemotherapeutic drugs, ibudilast, and lithium were monitored as described previously (12) using a FluoroMax-3 fluorometer with Datamax software and temperature control (Jobin Yvon Horiba, NJ) or a DeltaRam V fluorometer with Felix software and temperature control (Photon Technology International). Samples were excited at 270 nm, and spectra were collected between 280 and 400 nm at 20 °C. Experiments were performed with either 0.5 μg or 1.0 μg of NCS-1 and increasing concentrations from 0 to 1.0 μm Taxol or docetaxel, 0–0.9 μm vincristine, 0–3.0 μm oxaliplatin, 0–10 μm ibudilast, and 0–10 mm lithium. Additional experiments were performed with 1.0 μg of NCS-1 and either 2.0 μm ibudilast or 2.0 mm lithium with increasing concentrations of Taxol or vincristine to determine whether ibudilast or lithium interfered with the ability of NCS-1 to bind to the chemotherapeutic drugs. Control experiments with buffer (10 mm Hepes, 100 mm KCl, and 1 mm CaCl2) alone and increasing concentrations of each drug alone were subtracted from the experiments containing NCS-1. Changes in the peak height at 334 nm were plotted as a function of drug concentration to determine the binding constant (EC50) using the exponential analysis function of OriginPro 8.0.

Western Blot Analysis

The human neuroblastoma cell line, SHSY-5Y, was cultured as described previously (12, 24). Cells were treated for 6 h with 800 ng/ml Taxol with and without the addition of either 1 μm ibudilast or 500 μm and 5.0 mm lithium. Lysate preparation was performed as described previously (12, 15), and immunoblotting was performed using Invitrogen NuPage system and iBlot according to the manufacturer's protocol. Antibodies used were: anti-NCS-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-β-actin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-calpain 1 (Calbiochem), anti-calpain 2 (Abcam). Protein expression was quantified by scanning densitometry by UN-SCAN-IT (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT) or Odyssey 2.0 (LI-COR Biotechnology, Lincoln NE) and normalized to β-actin loading controls. All Western blotting experiments were performed with three independent cultures.

Live Cell Imaging

Live cell imaging was performed as described previously (12) on the human neuroblastoma line, SHSY-5Y, and the mouse neuroblastoma cell line, N2A. SHSY-5Y or N2A cells were treated with Taxol and ibudilast or lithium as described above, as well as with a combination of the two protective agents. SHSY-5Y cells were also treated for 6 h with 500 nm vincristine with and without 1.0 μm ibudilast or 5.0 mm lithium or a combination of both. N2A cells were treated with 800 ng/ml Taxol or 500 nm vincristine. Briefly, SHSY-5Y and N2A cells were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in Hepes buffer containing 1.3 mm CaCl2, 0.1% Pluronic F-127 and 5 μm Fluo-4 (Invitrogen). A Zeiss LSM 710 scanning laser confocal microscope equipped with a C-Apochromat ×40/1.2 water immersion objective (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) was used. Cells were excited with 1 μm ATP to induce a transient release of calcium from intracellular stores. After the calcium signal returned to base line following ATP stimulation, 10 μm thapsigargin was added to indicate that the intracellular stores were filled and the cells were viable. A minimum of 4–5 wells over several days with 80–150 total cells was compared for each condition. Calcium-induced fluorescence intensity ratio, F/F0, was plotted as a function of time in seconds with F0 calculated as the average of the first 10 points of the base line. Response duration was defined as the time the calcium signal remains consecutively over 50% of the peak value.

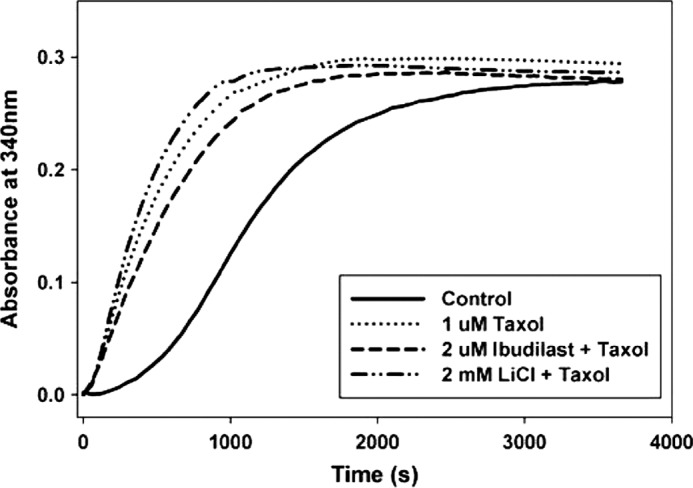

Microtubule Polymerization Assay

The Tubulin Polymerization Assay Kit (Cytoskeleton) was used to measure tubulin polymerization in the presence of Taxol and ibudilast or lithium. Experiments were performed following the standard manufacturer's protocol using a Corning half-area 96-well plate and a Tecan Infinite M200 spectrometer with Tecan i-control software. Each assay was performed with 3 mg/ml tubulin, and the effects of 1 μm Taxol with and without 2 μm ibudilast or 2 mm lithium were tested. Spectrometer readings of these assays were taken at 340 nm every minute for 1 h at 37 °C, and the results were scaled and plotted.

RESULTS

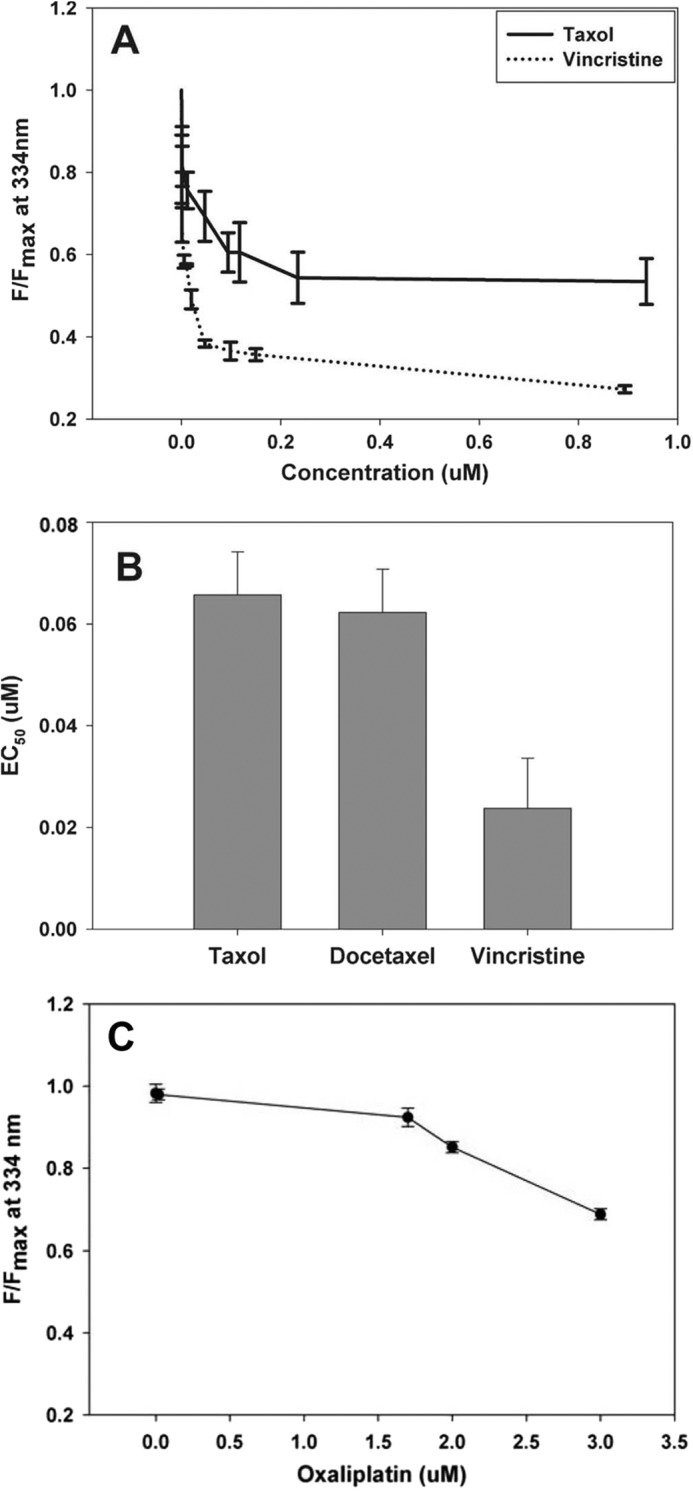

NCS-1 Binds Chemotherapeutic Drugs

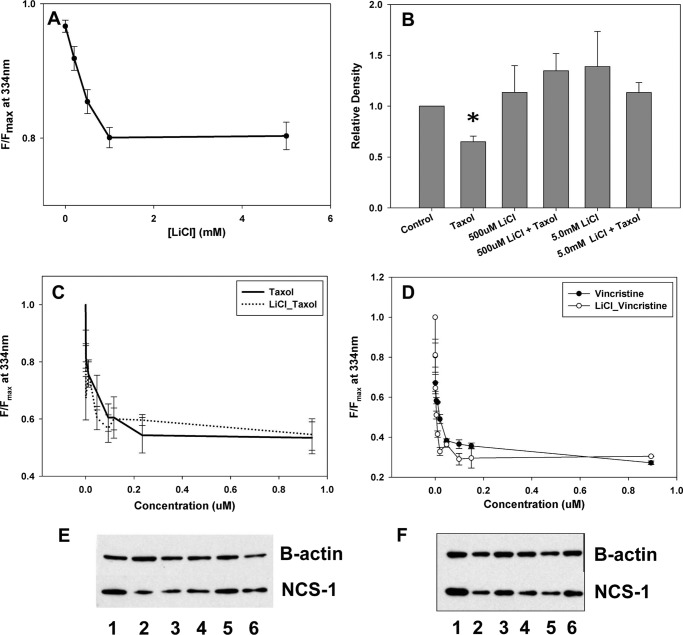

Binding between NCS-1 and various chemotherapeutic drugs was assessed using tryptophan fluorescence. Taxol, docetaxel, and vincristine all bind NCS-1 in the low micromolar range (Fig. 1, A and B). NCS-1 bound Taxol with an affinity of 0.066 ± 0.008 μm, docetaxel with an affinity of 0.062 ± 0.009 μm, and vincristine with an affinity of 0.024 ± 0.01 μm (Fig. 1, A and B). As a negative control, the interaction between oxaliplatin and NCS-1 was tested. Oxaliplatin did not bind NCS-1 (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Binding of NCS-1 to chemotherapeutic drugs. A, representative binding curve of NCS-1 with Taxol and vincristine. An assay utilizing the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of NCS-1 was used to determine the binding affinity with Taxol, docetaxel, and vincristine for NCS-1. B, binding affinity (EC50) for NCS-1 with Taxol, docetaxel, and vincristine. C, intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of NCS-1 was used to determine binding of NCS-1 with oxaliplatin. It was determined that oxaliplatin and NCS-1 do not bind (n = 4). Error bars, S.E.

Lithium Binds and Prevents NCS-1 Degradation

To verify that lithium binds to NCS-1 without interfering with the ability of NCS-1 to bind to the chemotherapeutic drugs, tryptophan fluorescence was tested in the presence and absence of each drug with lithium present. Lithium alone bound to NCS-1 with a binding affinity of 0.54 ± 0.05 mm (Fig. 2A). With increasing concentrations of Taxol or vincristine, the binding curves with NCS-1 were unchanged by the presence of 2.0 mm LiCl (Fig. 2, C and D). The binding affinities in the presence of lithium were 0.058 ± 0.009 μm and 0.02 ± 0.006 μm for Taxol and vincristine, respectively. To verify that NCS-1 is binding these drugs, NMR of NCS-1 in the presence and absence of the drugs was performed. The NMR shifted upon addition of the chemotherapeutic drugs, which confirmed binding to NCS-1 (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 2.

Lithium binds and prevents NCS-1 degradation. A, binding of NCS-1 with lithium. B, Western blot analysis of NCS-1 in the presence of either 500 μm or 5.0 mm LiCl in SHSY-5Y cells treated with Taxol showing NCS-1 levels similar to control cells (n = 4); *, p ≤ 0.05. All treatments were normalized to control cells. C, binding curve for NCS-1 and Taxol in the presence and absence of 2.0 mm LiCl. D, representative binding curve for NCS-1 and vincristine in the presence and absence of 2.0 mm LiCl. No significant difference was found in the ability of Taxol or vincristine to bind NCS-1 in the presence of lithium. E, representative Western blot showing NCS-1 levels are protected from Taxol-induced reductions with LiCl treatment. Lane 1, control; lane 2, Taxol; lane 3, 200 μm LiCl + Taxol; lane 4, 500 μm LiCl + Taxol; lane 5, 1.0 mm LiCl + Taxol; lane 6, 5 mm LiCl + Taxol. F, representative Western blot showing that NCS-1 levels are not significantly affected by LiCl treatment. Lane 1, control; lane 2, Taxol; lane 3, 200 μm LiCl; lane 4, 500 μm LiCl; lane 5, 1.0 mm LiCl; lane 6, 5 mm LiCl.

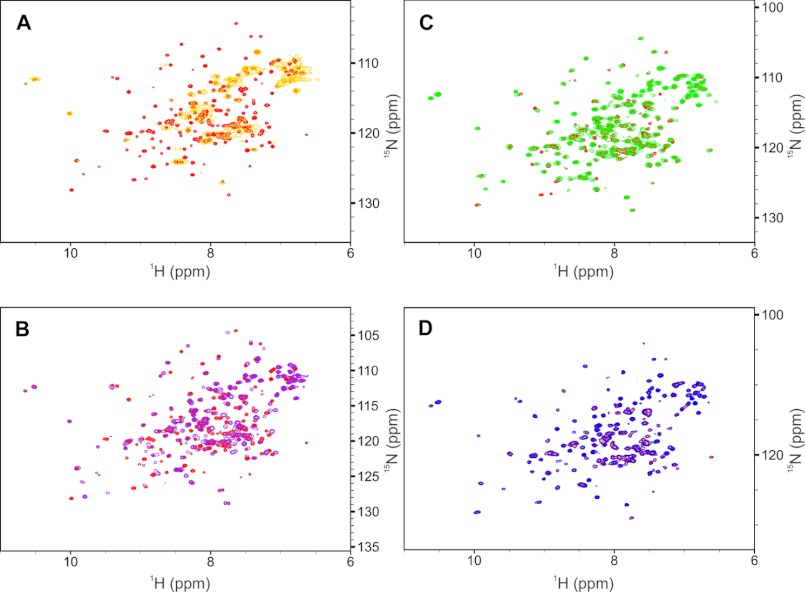

FIGURE 3.

NMR spectra of NCS-1 binding to ibudilast, vincristine sulfate, lithium, and Taxol. A, overlaid two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectra of 1.7 mm uniformly labeled 15N NCS1 apo (red contours) and holo (yellow contours) in phosphate-buffered saline at pH 7.4, 9% v/v dimethyl-d6 sulfoxide and 3 mm DTT. Vincristine sulfate ligand was at an 11-fold molar excess relative to the 15N NCS1 protein. B, overlaid two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectra of 1.7 mm uniformly labeled 15N NCS1 apo (red contours) and with ibudilast (violet contours) in phosphate-buffered saline at pH 7.4, 9% v/v dimethyl-d6 sulfoxide and 3 mm DTT. Ibudilast ligand was at a 3.5-fold molar excess relative to the 15N NCS1 protein. C, overlaid two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectra of 70 μm uniformly labeled 15N NCS1 apo (red contours) and with paclitaxel (green contours) in 50 mm Tris buffer, 100 mm KCl at pH 7.4, with 9% v/v dimethyl-d6 sulfoxide and 1 mm Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP). Paclitaxel ligand was added at a 10-fold molar excess relative to the 15N NCS1 protein and precipitated ligand removed through centrifugation. D, overlaid two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectra of 130 μm uniformly labeled 15N NCS1 apo (red contours) and with LiCl (blue contours) in 50 mm Tris buffer, 100 mm KCl at pH 7.4, with 9% v/v dimethyl-d6 sulfoxide and 1 mm TCEP. Lithium was added to a concentration of 10 mm in the holo spectrum. All buffers contained saturating concentrations of Ca2+ (∼20 mm) and Mg2+ (∼10 mm). Unlike the other ligands, there is a discrepancy between the NMR (shown here) and fluorescence results for lithium (Fig. 2A) which can be explained in one of two ways. First, lithium ions may be able to penetrate the NCS-1 structure and alter the solvation shell of buried tryptophans in a manner that potassium ions, with its larger ionic radius, cannot. Second, binding of lithium may involve only interactions with fixed side chain atoms with no alteration in chemical environment of backbone atoms. Proton chemical shifts are reported relative to 3-(trimethylsilyl)-1-propanesulfonic acid referenced to 0 ppm. All NMR experiments were conducted on a Varian INOVA 600 MHz spectrometer using a 5-mm triple-resonance probe equipped with triple-axis pulsed magnetic field gradients and utilized pulse sequences from the Varian BioPack User Library (Varian, Palo Alto, CA) and processed using NMRPipe (Refs. 29–31).

Western blot analysis was used to show that treatment of SHSY-5Y cells, a neuroblastoma cell line, with Taxol for 6 h led to a reduction (35.1 ± 1.3%) in NCS-1 levels. Treatment of cells with either 500 μm or 5.0 mm LiCl alone did not significantly affect NCS-1 levels. Cells treated for 6 h with lithium and Taxol showed that NCS-1 levels were similar to those of the control cells (Fig. 2, B, E, and F). Both concentrations of lithium tested were able to prevent NCS-1 degradation by Taxol.

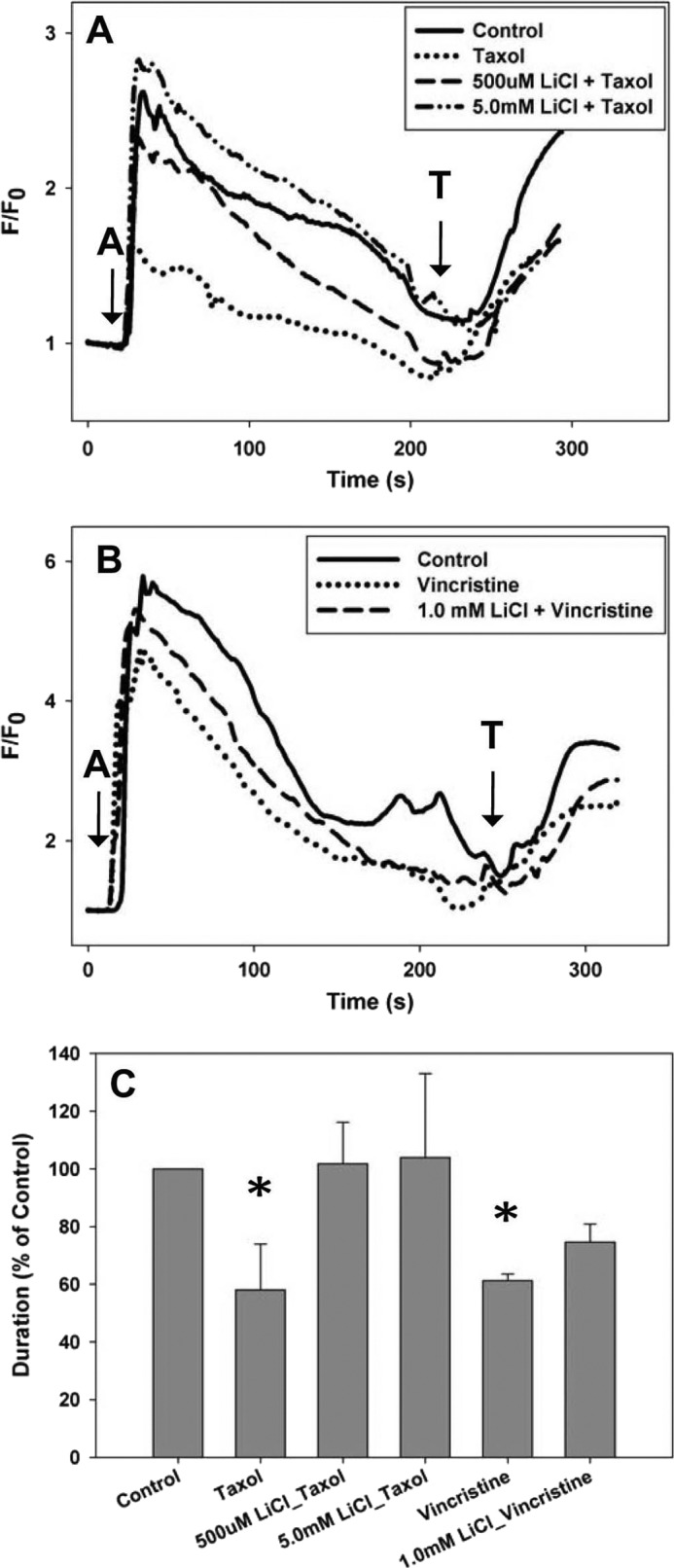

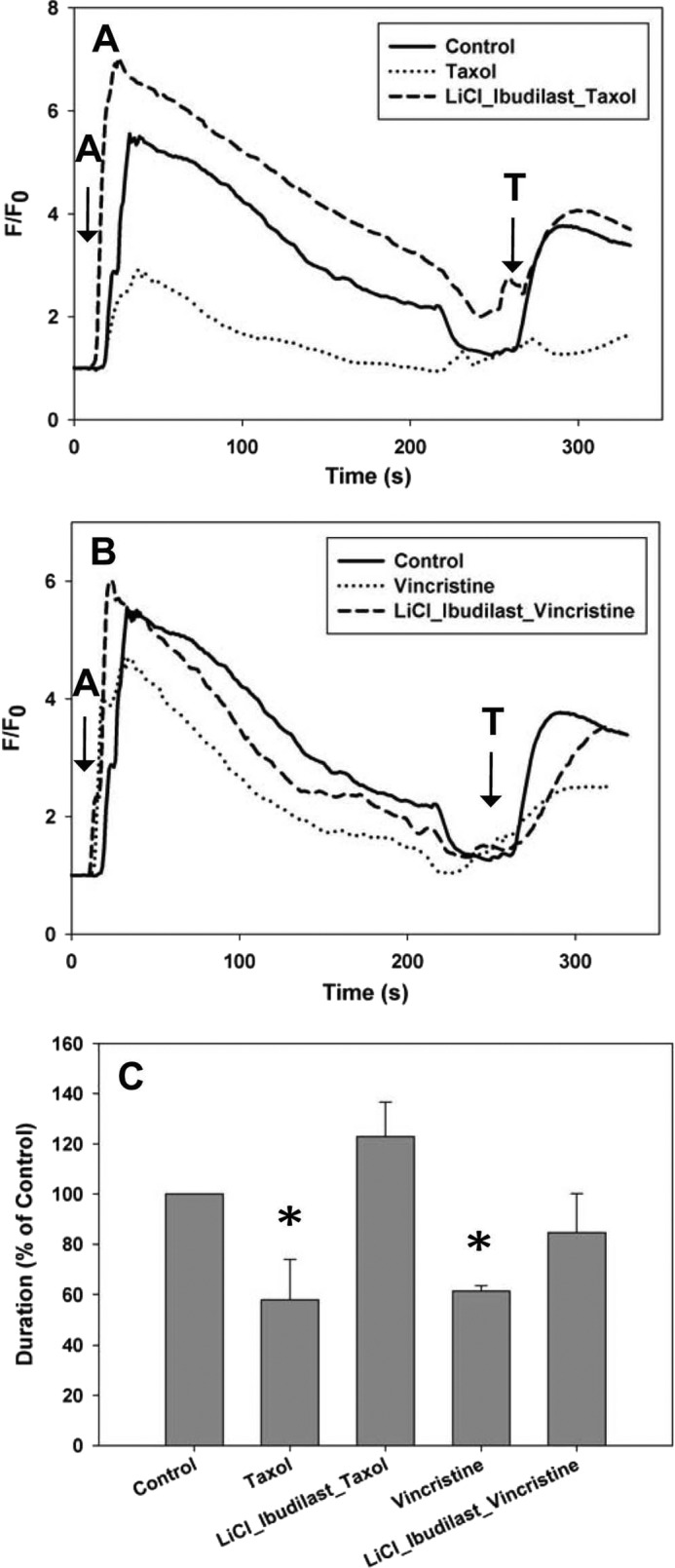

Lithium Protects Calcium Signaling during Taxol Treatment

Lithium was tested to determine whether it could prevent Taxol-dependent reductions in intracellular calcium signaling in SHSY-5Y. NCS-1 is known to positively modulate InsP3R-mediated Ca2+ release; therefore, addition of extracellular ATP to activate plasma membrane P2Y receptors and initiate the phosphoinositide signaling pathway and InsP3R-dependent Ca2+ oscillations was used to stimulate cells (15). A marked reduction in both the amplitude (50 ± 1.0%) and duration (42 ± 10.1%) of intracellular calcium signaling was found in Taxol-treated SHSY-5Y cells in the presence of extracellular calcium (Fig. 4, A and C). Similar results were also found in another neuroblastoma cells line, N2A cells (Fig. 5A). The presence of either 500 μm or 5.0 mm LiCl maintained both the amplitude and duration of the calcium signal that would have been reduced by treatment with Taxol for 6 h (Fig. 4, A and C). A similar protective effect of lithium (5 mm) on the amplitude and duration of the calcium signal in N2A cells was also observed (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 4.

Lithium maintains calcium signaling in SHSY-5Y cells. A, the intracellular calcium signal was measured in the presence of external calcium. 500 μm and 5.0 mm LiCl maintained the calcium signal in cells treated for 6 h with Taxol to the level of control cells. B, 1.0 mm LiCl maintained the calcium signal in cells treated for 6 h with vincristine to the level of control cells. (A = 1 μm ATP; T = 10 μm thapsigargin). C, comparison of the normalized response durations to 1 μm ATP in control cells, cells treated with Taxol or vincristine, and cells treated with lithium and Taxol or vincristine. All treatments are normalized to control cells. All values are mean ± S.E. (error bars); *, p ≤ 0.05.

FIGURE 5.

Lithium and ibudilast maintain calcium signaling in N2A cells. A, the intracellular calcium signal was measured in the presence of external calcium. With 6-h treatment of Taxol, the duration of the calcium transients was reduced by on average 37%, and calcium transients were reduced by 29% on average with 6-h treatment of vincristine. B, 5.0 mm LiCl maintained the calcium signal in cells treated for 6 h with Taxol to the level of control cells. C, 2 μm ibudilast maintained the calcium signal in cells treated for 6 h with Taxol to the level of control cells (A = 1 μm ATP; T = 10 μm thapsigargin).

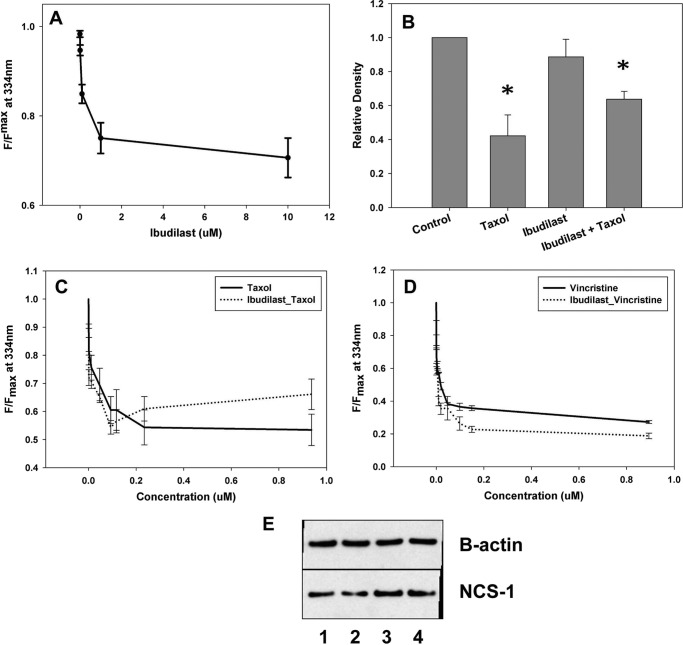

Ibudilast Binds and Prevents NCS-1 Degradation

To verify that ibudilast binds to NCS-1 without interfering with the ability of NCS-1 to bind the chemotherapeutic drugs, tryptophan fluorescence was monitored in the presence and absence of each drug with ibudilast present. NMR and tryptophan fluorescence showed that ibudilast alone bound NCS-1 with an affinity of 0.3 + 0.07 μm (Figs. 6A and 3B). With increasing concentrations of Taxol or vincristine, the binding curves with NCS-1 were found to be similar for each drug in the presence or absence of 2.0 μm ibudilast (affinities of 0.06 ± 0.004 μm and 0.041 ± 0.02 μm, respectively; p > 0.4 (Fig. 6, C and D). There was no significant difference found between binding affinities in the presence of ibudilast.

FIGURE 6.

Ibudilast binds and prevents NCS-1 degradation. A, binding of NCS-1 with ibudilast. B, Western blot analysis showing that 6-h treatment of SHSY-5Y cells with 800 ng/ml Taxol significantly reduces NCS-1 levels. The presence of 1 μm ibudilast in those cells treated with Taxol partially restored NCS-1 levels back to that of control cells (n = 3). *, p ≤ 0.05. All treatments were normalized to control cells. C, binding curve for NCS-1 and Taxol in the presence and absence of 1 μm ibudilast. D, representative binding curve for NCS-1 and vincristine in the presence and absence of 1 μm ibudilast. No significant difference was found in the ability of Taxol or vincristine to bind NCS-1 in the presence of ibudilast. E, representative Western blot showing that NCS-1 levels are protected from Taxol-induced reductions with ibudilast treatment. Lane 1, control; lane 2, Taxol; lane 3, 1 μm ibudilast + Taxol; lane 4, 1 μm ibudilast.

Western blot analysis revealed that treatment of SHSY-5Y cells with 1 μm ibudilast alone did not significantly affect NCS-1 levels. Cells treated with both ibudilast and Taxol for 6 h had NCS-1 levels partially restored to that of the control cells (Fig. 6, B and E).

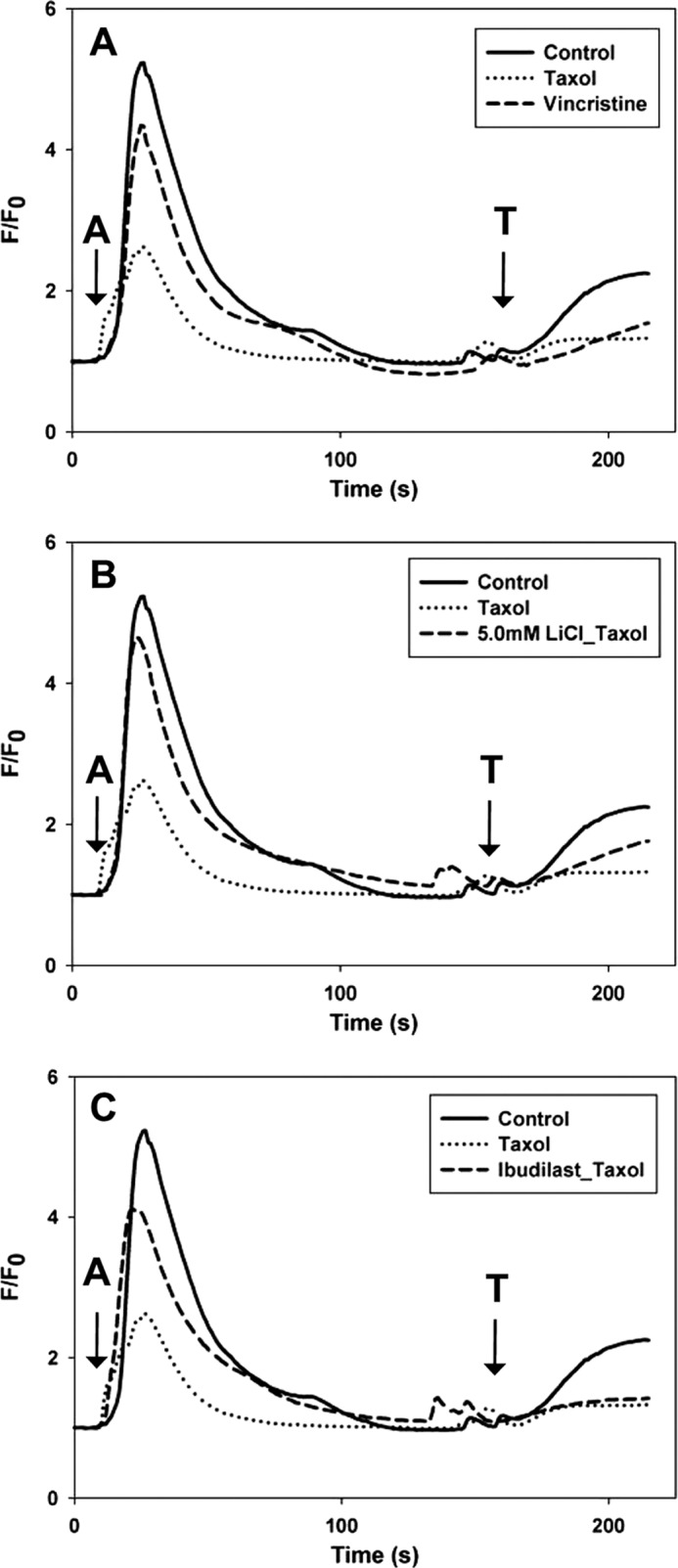

Ibudilast Protects Calcium Signaling during Taxol Treatment

Ibudilast was tested to determine whether it could inhibit Taxol-dependent reductions in intracellular calcium signaling in SHSY-5Y. During treatment with Taxol, the presence of 1 μm ibudilast maintained both the amplitude and duration of the calcium signal in SHSY-5Y cells (Fig. 7, A and C). Ibudilast (2 μm) had a similar protective effect in N2A cells (Fig. 5C).

FIGURE 7.

Ibudilast maintains calcium signaling in SHSY-5Y cells. A, the intracellular calcium signal was measured in the presence of external calcium. With 6-h treatment with Taxol, the duration of calcium transients was reduced by 42 ± 10.1%. 1 μm ibudilast maintained the calcium signal in cells treated for 6 h with Taxol to the levels of control cells. B, with 6-h treatment with vincristine, the duration of the calcium transients was reduced by 38.8 ± 2.3%. 1 μm ibudilast maintained the calcium signal in cells treated for 6 h with vincristine to the level of control cells (A = 1 μm ATP; T = 10 μm thapsigargin). C, comparison of the normalized response durations to 1 μm ATP in control cells, cells treated with Taxol or vincristine, and cells treated with ibudilast and Taxol or vincristine. All treatments are normalized to control cells. All values are mean ± S.E. (error bars); *, p ≤ 0.05.

Vincristine Reduces Calcium Signaling

Vincristine was tested to see whether another chemotherapeutic drug known to cause peripheral neuropathy had similar effects on intracellular calcium signaling. SHSY-5Y cells were treated with vincristine for 6 h and showed a reduction in both the amplitude (18 ± 4%) and duration (39 ± 2%) of the intracellular calcium signal, although it was not to the extent seen with Taxol (Figs. 4B and 7B). Similar results were also found in N2A cells (Fig. 5A). The presence of 1 μm ibudilast maintained both the amplitude and duration of the calcium signal in SHSY-5Y cells (Fig. 6, B and C). The presence of 1.0 mm LiCl inhibited the reduction in amplitude and duration of the calcium signal associated with treatment with vincristine for 6 h (Fig. 4, B and C).

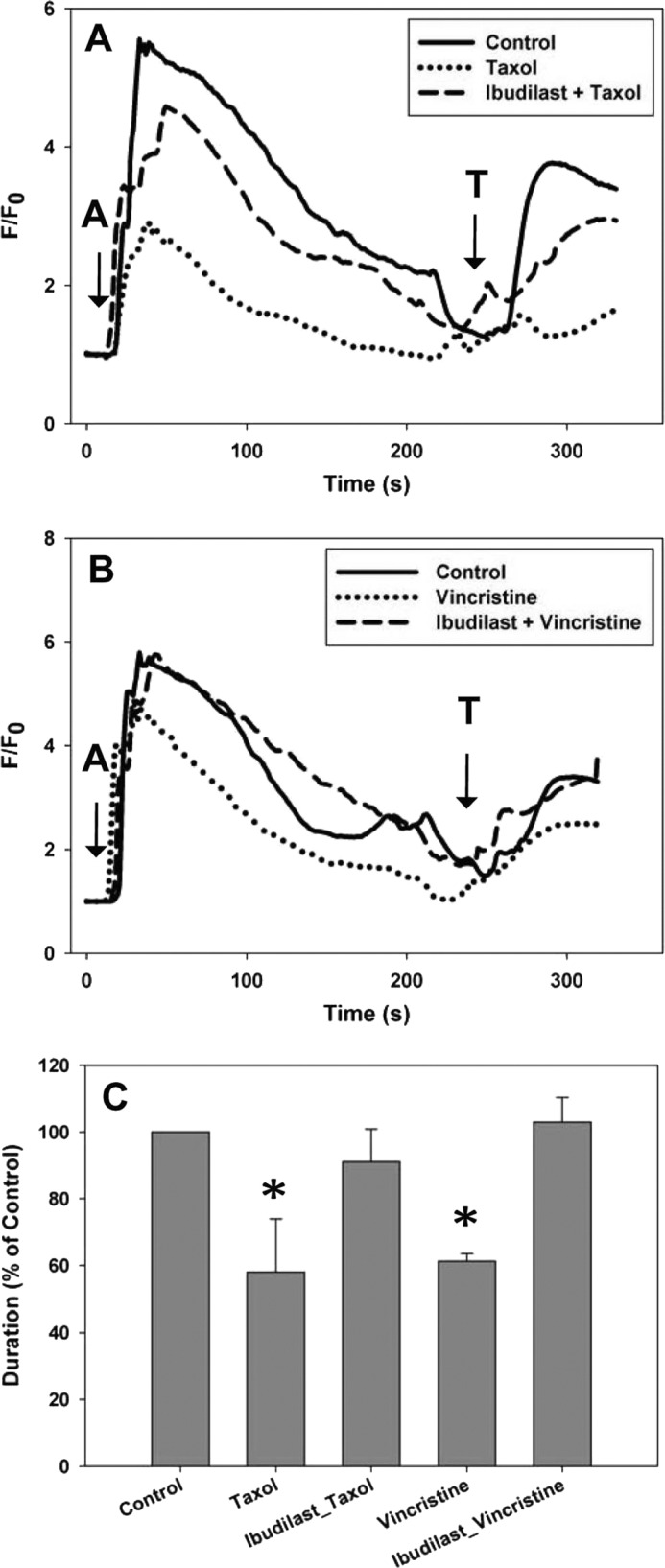

Both lithium and ibudilast independently protected cells from Taxol- or vincristine-induced decreases in calcium signaling. To determine whether there were additive or synergetic effects, SHSY-5Y cells were treated with lithium and ibudilast simultaneously during the 6-h chemotherapeutic treatment. No consistent additional protection was found in cells with lithium and ibudilast compared with either compound alone (Figs. 8). These results suggest that there are no synergistic effects to using a combination of both lithium and ibudilast.

FIGURE 8.

Lithium and ibudilast together do not have additive effects on the calcium signal in SHSY-5Y cells. A, the intracellular calcium signal was measured in the presence of external calcium. 0.5 mm LiCl with 0.5 μm ibudilast maintained the calcium signal in cells treated for 6 h with Taxol to the level of control cells. B, 2.5 mm LiCl with 0.5 μm ibudilast maintained the calcium signal in cells treated for 6 h with vincristine to the level of control cells. C, comparison of the normalized response durations to 1 μm ATP in control cells, cells treated with Taxol or vincristine, and cells treated with lithium and ibudilast in addition to each chemotherapeutic drug is shown. In neither case was better protection seen than with either lithium or ibudilast alone. All treatments are normalized to control cells. All values are mean ± S.E. (error bars); *, p ≤ 0.05.

Lithium and Ibudilast Do Not Interfere with the Ability of Taxol to Enhance Microtubule Assembly

To verify that lithium and ibudilast were not affecting the functional interaction between tubulin and Taxol, a tubulin polymerization assay was utilized which monitors microtubule assembly (see “Experimental Procedures”). Taxol enhanced microtubule assembly compared with the control with tubulin alone (Fig. 9). The presence of either 2.0 mm LiCl or 2.0 μm ibudilast did not significantly alter the ability of Taxol to enhance tubulin polymerization (Fig. 9).

FIGURE 9.

Lithium and ibudilast do not interfere with the ability of Taxol to enhance microtubule assembly. Tubulin polymerization curves for 1 μm Taxol in the absence and presence of either 2 μm ibudilast or 2 mm lithium are shown. The control curve contains 3 mg/ml tubulin alone. Polymerization was assessed for 1 h at 37 °C.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to identify treatment options that prevent adverse effects to cells by the use of the current chemotherapeutic drug agents, while still maintaining their anti-cancer efficacy. The exact mechanism underlying Taxol-induced peripheral neuropathy, and potentially other chemotherapeutic drugs, is not well understood. However, previous literature suggests that the interactions among Taxol, NCS-1, calpain, and InsP3R are important in this pathway (10–12, 15). Several chemotherapeutic drugs are believed to cause an enhanced calcium signal leading to hyperactivation of neurons (25). The results presented here support the importance of these interactions and the resulting enhanced calcium signal. Therefore, we believe it is the initial enhanced calcium signal that leads to the pathological changes in neurons that results in peripheral neuropathy. This paper found that the addition of two candidate compounds, lithium and ibudilast, when given prior to Taxol treatment, are able to inhibit some of the deleterious changes to neuroblastoma cells.

A potential mechanism for peripheral neuropathy has been proposed where Taxol binds to NCS-1, which enhances NCS-1 binding to the InsP3R, resulting in an initial increase in calcium release from intracellular stores. The increase in calcium levels activates calpain, which then cleaves NCS-1. The lower NCS-1 levels in the cell, in turn, leads to decreased activation of the InsP3R, resulting in an attenuated calcium signal (12) as seen in the calcium signaling experiments in this study. Earlier studies have shown that Taxol diminishes the InsP3R-dependent calcium signal through calpain degradation of NCS-1 (11, 12). This study confirmed this finding and then showed that the addition of either lithium or ibudilast to SHSY-5Y cells, a neuroblastoma cell line, treated with Taxol resulted in a protection of NCS-1 levels. In vivo studies using mice treated with Taxol confirmed that calpain activity is increased by Taxol treatment and that the addition of lithium or ibudilast prior to Taxol treatment can inhibit this enhanced activation of calpain (26). The cell-based experiments reported here and the in vivo studies (26) provide strong support for our hypothesis that pretreatment with lithium and ibudilast inhibits the calpain cleavage of NCS-1.

Taxol has been previously shown to interact with NCS-1 (10, 11). This study confirmed that Taxol, as well as two other chemotherapeutic drugs, docetaxel and vincristine, bind to NCS-1 in the low micromolar range. Although it is likely that the interaction between these drugs and NCS-1 is not the only step linking the enhanced calcium signal to the adverse changes occurring in the neurons, it is clear that NCS-1 is an important component in the overall mechanism. It is likely that NCS-1 will be a good marker for testing other strategies for preventing chemotherapy adverse events. This study also describes a fast and efficient method to assess binding of drugs with NCS-1; monitoring the changes in the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of NCS-1 is easier than monitoring NMR changes (Fig. 3) or phage display selection of binding proteins (10). The fluorescence method was used to show that NCS-1 does not bind oxaliplatin (Fig. 1C), a chemotherapeutic drug that induces a cold allodynia but does not bind tubulin, does not bind NCS-1 and has no effect on InsP3R-dependent intracellular calcium signaling in SHSY-5Y cells (15).

Both Taxol and vincristine bind to tubulin, despite having opposite effects on microtubule stability (5, 8). Previously, neuronal cells treated with Taxol for 6 h were found to have reduced intracellular calcium signals (12). This study found a similar reduction in intracellular calcium signaling in cells treated with either Taxol or vincristine. Lithium and ibudilast were both found to protect against the diminished calcium signal that occurs by treatment of neuronal cells with either Taxol or vincristine. This could be because both of these candidate compounds bind to NCS-1 without affecting Taxol or vincristine binding. Our results suggest that both lithium and ibudilast possess the ability to inhibit the unwanted changes to neuronal cells caused by treatment regimes that utilize microtubule-based chemotherapeutic drugs, without altering their chemotherapeutic efficacies.

In the past, lithium and ibudilast were tested as potential treatment options for the treatment of Taxol-induced peripheral neuropathy; however, neither compound was previously considered as a preventative measure against peripheral neuropathy (22, 23, 27, 28). This study clearly shows that these candidate compounds are able to inhibit chemotherapy-induced changes in neuronal cells. The addition of lithium or ibudilast allows NCS-1 levels and intracellular calcium signaling to be maintained during administration of microtubule-based chemotherapeutic drugs. As neither lithium or ibudilast was found to interfere with the ability of NCS-1 or tubulin to bind to and interact with these chemotherapeutic drugs, we suggest that both compounds are able to inhibit peripheral neuropathy without hindering the chemotherapeutic efficacy of these drugs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ivana Kuo, Michelle Mo, and Colleen Feriod for invaluable advice regarding the design of the experiments and thoughtful discussions and comments on the manuscript; Dr. Ben Turk for invaluable advice regarding the measurement of the ligand interactions with NCS-1; and Dr. Bliss Forbush for advice and for the use of his fluorometer.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK57751 and DK61747 and National Institutes of Health Training Grant 5T32DK 007356-32 administered by the Department of Digestive Diseases at Yale University. This work was also supported by Department of Defense for Breast Cancer Research Grant J00181.

- NCS-1

- neuronal calcium sensor-1

- InsP3R

- inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate receptor

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hilkens P. H., ven den Bent M. J. (1997) Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2, 350–361 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mielke S., Sparreboom A., Mross K. (2006) Peripheral neuropathy: a persisting challenge in paclitaxel-based regimens. Eur. J. Cancer 42, 24–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Spencer C. M., Faulds D. (1994) Paclitaxel: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential in the treatment of cancer. Drugs 48, 794–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Preston N. J. (1996) Paclitaxel (Taxol): a guide to administration. Eur. J. Cancer Care 5, 147–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schiff P. B., Fant J., Horwitz S. B. (1979) Promotion of microtubule assembly in vitro by Taxol. Nature 277, 665–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lyseng-Williamson K. A., Fenton C. (2005) Docetaxel: a review of its use in metastatic breast cancer. Drugs 65, 2513–2531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hennequin C., Giocanti N., Favaudon V. (1995) S-phase specificity of cell killing by docetaxel (Taxotere) in synchronised HeLa cells. Br. J. Cancer 71, 1194–1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Muthuraman A., Singh N., Jaggi A. S. (2011) Protective effect of Acorus calamus L. in rat model of vincristine-induced painful neuropathy: an evidence of anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative activity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 49, 2557–2563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang M. S., Davis A. A., Culver D. G., Wang Q., Powers J. C., Glass J. D. (2004) Calpain inhibition protects against Taxol-induced sensory neuropathy. Brain 127, 671–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boehmerle W., Splittgerber U., Lazarus M. B., McKenzie K. M., Johnston D. G., Austin D. J., Ehrlich B. E. (2006) Paclitaxel induces calcium oscillations via an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and neuronal calcium sensor 1-dependent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 18356–18361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boehmerle W., Zhang K., Sivula M., Heidrich F. M., Lee Y., Jordt S. E., Ehrlich B. E. (2007) Chronic exposure to paclitaxel diminishes phosphoinositide signaling by calpain-mediated neuronal calcium sensor-1 degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 11103–11108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Benbow J. H., DeGray B., Ehrlich B. E. (2011) Protection of neuronal calcium sensor 1 protein in cells treated with paclitaxel. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 34575–34582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Philippov P. P., Koch K. W. (eds) (2006) Neuronal Calcium Sensor Proteins, Nova Science Publishers [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burgoyne R. D., Weiss J. L. (2001) The neuronal calcium sensor family of Ca2+-binding proteins. Biochem. J. 353, 1–12 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schlecker C., Boehmerle W., Jeromin A., DeGray B., Varshney A., Sharma Y., Szigeti-Buck K., Ehrlich B. E. (2006) Neuronal calcium sensor-1 enhancement of InsP3 receptor activity is inhibited by therapeutic levels of lithium. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 1668–1674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blachford C., Celić A., Petri E. T., Ehrlich B. E. (2009) Discrete proteolysis of neuronal calcium sensor-1 (NCS-1) by μ-calpain disrupts calcium binding. Cell Calcium 46, 257–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aravind P., Chandra K., Reddy P. P., Jeromin A., Chary K. V., Sharma Y. (2008) Regulatory and structural EF-hand motifs of neuronal calcium sensor-1: Mg2+ modulates Ca2+ binding, Ca2+-induced conformational changes, and equilibrium unfolding transitions. J. Mol. Biol. 376, 1100–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ehrlich B. E., Diamond J. M. (1980) Lithium, membranes, and manic-depressive illness. J. Membr. Biol. 52, 187–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shimizu T., Shibata M., Wakisaka S., Inoue T., Mashimo T., Yoshiya I. (2000) Intrathecal lithium reduces neuropathic pain responses in a rat model of peripheral neuropathy. Pain 85, 59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koh P. O., Undie A. S., Kabbani N., Levenson R., Goldman-Rakic P. S., Lidow M. S. (2003) Up-regulation of neuronal calcium sensor-1 (NCS-1) in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenic and bipolar patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 313–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cho Y., Crichlow G. V., Vermeire J. J., Leng L., Du X., Hodsdon M. E., Bucala R., Cappello M., Gross M., Gaeta F., Johnson K., Lolis E. J. (2010) Allosteric inhibition of macrophage migration inhibitory factor revealed by ibudilast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11313–11318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ledeboer A., Hutchinson M. R., Watkins L. R., Johnson K. W. (2007) Ibudilast (AV-411): a new class therapeutic candidate for neuropathic pain and opioid withdrawal syndromes. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 16, 935–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ledeboer A., Liu T., Shumilla J. A., Mahoney J. H., Vijay S., Gross M. I., Vargas J. A., Sultzbaugh L., Claypool M. D., Sanftner L. M., Watkins L. R., Johnson K. W. (2006) The glial modulatory drug AV411 attenuates mechanical allodynia in rat models of neuropathic pain. Neuron Glia Biol. 2, 279–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Estrada M., Uhlen P., Ehrlich B. E. (2006) Ca2+ oscillations induced by testosterone enhance neurite outgrowth. J. Cell Sci. 119, 733–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ramos-Franco J., Caenepeel S., Fill M., Mignery G. (1998) Single channel function of recombinant type-1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor ligand binding domain splice variants. Biophys. J. 75, 2783–2793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mo M., Erdelyi I., Szigeti-Buck K., Benbow J. H., Ehrlich B. E. (2012) FASEB J., in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hama A. T., Broadhead A., Lorrain D. S., Sagen J. (2012) The antinociceptive effect of the asthma drug ibudilast in rat models of peripheral and central neuropathic pain. J. Neurotrauma 29, 600–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pourmohammadi N., Alimoradi H., Mehr S. E., Hassanzadeh G., Hadian M. R., Sharifzadeh M., Bakhtiarian A., Dehpour A. R. (2012) Lithium attenuates peripheral neuropathy induced by paclitaxel in rats. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 110, 231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wishart D. S., Sykes B. D. (1994) The 13C chemical-shift index: a simple method for the identification of protein secondary structure using 13C chemical-shift data. J. Biomol. NMR 4, 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cornilescu G., Delaglio F., Bax A. (1999) Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J. Biomol. NMR 13, 289–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patterson R. L., Boehning D., Snyder S. H. (2004) Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors as signal integrators. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 437–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]