Abstract

The current practice of cell therapy, in which multipotent or terminally differentiated cells are injected into tissues or intravenously, is inefficient. Few therapeutic cells are retained at the site of administration and engraftment is low. An injectable and biologically appropriate vehicle for delivery, retention, growth and differentiation of therapeutic cells is needed to improve the efficacy of cell therapy. We focus on a hyaluronan-based semi-synthetic extracellular matrix (sECM), HyStem®, which is a manufacturable, approvable and affordable clinical product. The composition of this sECM can be customized for use with mesenchymal stem cells as well as cells derived from embryonic or induced pluripotent sources. In addition, it can support therapeutic uses of progenitor and mature cell populations obtained from skin, fat, liver, heart, muscle, bone, cartilage, nerves and other tissues. This overview presents four pre-clinical uses of HyStem® for cell therapy to repair injured vocal folds, improve post-myocardial infarct heart function, regenerate damaged liver tissue and restore brain function following ischemic stroke. Finally, we address the real-world limitations – manufacture, regulation, market acceptance and financing – surrounding cell therapy and the development of clinical combination products.

Keywords: HyStem®, Cell therapy, ECM, Hyaluronic acid, Cell engraftment

1. Evolving a culture of impact

The reality of translating biomaterials as research tools in academic laboratories into products that companies sell to physicians for clinical care has taken center stage in the past few years. There is an evolutionary change – some might say a revolutionary change – occurring at universities. Rather than remaining a traditional “ivory tower”– an inward-focused culture that the public views as irrelevant to their lives – many universities are moving towards an open culture based on impact as the unifying metric. To convert academic technologies into products, the inventions at universities require implementation and commercialization; this is true innovation. Indeed, no technology reaches the public unless it is commercialized.

There is, therefore, a translational imperative to implement the creation of products to address real-world needs. The pursuit of this goal by both students and faculty broadens the scope of scholarly activities in an exciting, important way. Participation in translational and transdisciplinary team activities engages and excites students in a way no lecture or laboratory course possibly could. The ultimate deliverable of entrepreneurial student and faculty scholars is to use science to serve the public good by making life better and creating jobs. This overview serves to highlight a case study of how academic research resulted in new products for clinical use in human and veterinary patients. Importantly, it also serves to emphasize how three seemingly independent processes were crucial in this transformation: (i) maturation of the technology, (ii) development of a better commercialization infrastructure within the university and (iii) recognition of the obligation of faculty to help their students do work that will have real impact on the lives of people.

2. Deconstructing the extracellular matrix (ECM)

A synthetic substitute for the ECM should recapitulate the principal functions of the natural ECM in orchestrating cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, angiogenesis and invasion [1]. The design criteria should include: (i) control of composition, (ii) control of compliance, (iii) control of biodegradation in vitro and in vivo, (iv) control of fabrication and physical forms, (v) control of delivery modality, (vi) batch to batch consistency, (vii) ease of use at physiological temperature and pH, and (ix) seamless translation to a clinical product [2]. In addition, perhaps the most important criterion for an ECM substitute should be the clinical imperative: physicians require the material to produce – in conjunction with therapeutic cells – the desired biological and clinical outcome.

Modular semi-synthetic ECMs (sECMs) offer maximum flexibility for addition of soluble factors, particles and cells [3]. The “living HA” technology reviewed herein was first described by one of us (G.D.P.) in 2002 [4] and reviewed in 2011 [5]. Following the paradigm described above, Glycosan BioSystems was launched (G.D.P. and W.P.T), and licensed the sECM technology in order to develop research and potential clinical uses. In March 2011, Glycosan was acquired by BioTime in order to deliver proprietary cell lines for cell therapy. The sECMs are assembled from living biopolymers based on chemically modified hyaluronan (HA) [6,7]. The living biopolymers are so named because a modified HA can be combined with cells, soluble factors and particles, and subsequently crosslinked to form a hydrogel in vivo in a tissue in need of treatment. HA is a ubiquitous ECM glycosaminoglycan that is evolutionarily conserved from the simplest prokaryotes to complex tissues of eukaryotes. Importantly, the crosslinked HA gels are intrinsically anti-inflammatory, similar to unmodified high molecular weight HA, as evidenced increased IL-10 production by T-regulatory cells [8]. In addition, different levels of crosslinking of the thiol-modified HA and gelatin components provide sECMs of different stiffnesses [9]. A soft gel based primarily on HA appears to be critical for control of liver progenitor cell differentiation [10], for endothelial progenitor cells to form vascular networks [11] and for achieving full functionality of cardiomyocytes [12], among other uses. The sECMs also allow inclusion of the appropriate biological cues needed to simulate the complexity of the ECM of a given tissue and offer a manufacturable, highly reproducible, flexible, FDA-approvable and affordable vehicle for cell expansion and differentiation in three dimensions [5].

3. Translation in progress

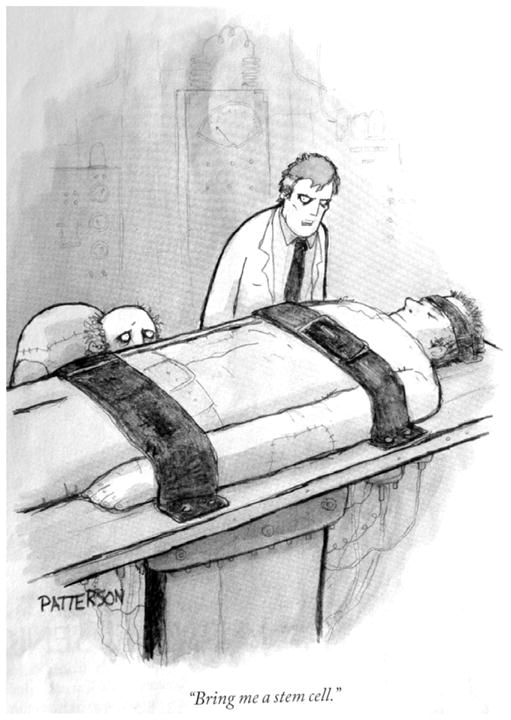

Cell therapy requires a source of therapeutic cells as well as a delivery system to retain the cells at the site of repair. A 2007 Patterson cartoon in the The New Yorker illustrates this requirement in a meaningful, yet tongue-in-cheek way (Fig. 1). The sECM materials are ideally suited for the “mad scientist” (an unfortunate stereotype) to use to deliver the stem cells; the assistant “Igor” is the source of the stem cells. Actually, there are many corporate “Igors” now in existence, each having its proprietary processes for obtaining multipotent (or terminally differentiated) cell lines for clinical use. Table 1 summarizes many of these companies, including the proprietary cell line, the tissue source and the potential clinical application(s) for these cells. Glycosan/BioTime works with a growing number of companies and academic collaborators who wish to employ an sECM such as HyStem® to facilitate the translation of combination products into the clinic [13]. Five examples in quite different tissues are described briefly below.

Fig. 1.

Cell therapy requires a source of therapeutic cells as well as a delivery system to retain the cells at the site of repair. Shown under license from The New Yorker. See Table 1 for a list of “Igors” who can deliver stem cells.

Table 1.

Companies with commercial interest in the development of stem cell-based therapeutics.

| Corporate “Igor” | Location | Cell type | Product name | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aastrom Biosciences | Ann Arbor, MI | Allogeneic bone marrow derived stem cells | Ixmyelocel-T | Critical limb ischemia (Phase III) |

| Advanced Cell Technologies | Santa Monica, CA | Embryonic derived retinal pigmented epithelial cells | MA09-hRPE | Stargardt’s macular dystrophy (Phase I/II), dry age-related macular degeneration (PhaseI/II) |

| Embryonic derived hemangioblasts | Circulatory and vascular system (Pre-clinical) | |||

| Autologous adult derived myoblasts | Congestive heart failure (Phase I complete) | |||

| Aldagen | Durham, NC | Autologous bone marrow derived stem cells | ALD 301, ALD 201, ALD 401 | Critical limb ischemia (Phase I/II complete), ischemic heart failure (Phase I complete), ischemic stroke (Phase II approved) |

| Athersys | Cleveland, OH | Allogeneic bone marrow derived stem cells | MultiStem® | Intestinal bowel disease (Phase II), stroke (Phase II), GvHD (Phase I complete), and acute myocardial infarction (Phase I) |

| Bioheart | Sunrise, FL | Autologous muscle derived stem cells | MyoCell® | Ischemic heart failure (PhaseII/III) |

| BioTime | Alameda, CA | Embryonic derived chondrogenic progentior cells | OTX-CP07 | Cartilage repair (Pre-clinical) |

| Embryonic derived endothelial progenitor cells | Vascular diseasea and ischemic injury (Pre-clinical) | |||

| Embryonic derived retinal pigmented epithelial cells | OpRegen® | Dry age-related macular degeneration (Pre-clinical) | ||

| Capricor | Los Angeles, CA | Autologous cardiosphere derived cells | Myocardial infarction, ventricular dysfunction (Phase I complete) | |

| Allogeneic cardiosphere derived cells | CAP-1002 | Myocardial infarction (Phase II) | ||

| Celgene Cellular Therapeutics | Summit, NJ | Placenta derived stem cells | PDA-001 | Treatment-resistent Crohn’s disease (Phase I) |

| Cellerant Therapeutics | San Carlos, CA | Expanded myeloid progenitor cells | CLT-008 | Cord blood transplants (Phase I complete), neutropenia (Phase I), acute radiation syndrome (Pre-clinical) |

| Cytori | La Jolla, CA | Autologous adipose derived stem cells | Ischemic heart disease (Phase II/III) | |

| Garnet BioTherapeutics | Malvern, PA | Allogeneic bone marrow derived stem cells | GBT 009 | Abdominal scarring (Phase II) |

| MediStem | San Diego, CA | Universal endometrial regenerative cells | Critical limb ischemia (Phase I) | |

| Mesoblast | Melbourne, AU | Allogeneic bone marrow derived precursor cells | Revascor™ | Heart failure (Phase II) |

| Allogeneic bone marrow derived precursor cells | Replicart™ | Cartilage degeneration after injury or ACL repair (Phase II) | ||

| NeoStem | New York, NY | Autologous bone marrow derived stem cells | AMR-001 | Acute myocardial infarction (Phase II), autoimmune diseases (Phase I) |

| Autologous bone marrow derived embryonic like stem cells | VSELTM | Macular degeneration (Pre-clinical), liver regeneration (pre-clinical), osteoporosis (pre-clinical), chronic wounds (preclinical), motor neurons (pre-clinical) | ||

| NeuralStem | Rockville, MD | Spinal cord derived neural stem cells | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (Phase I) | |

| Osiris | Columbia, MD | Allogeneic bone marrow derived stem cells | Prochymal | GvHD (Phase III), Crohn’s disease (Phase III), cardiac (Phase II), type I diabetes (Phase II) |

| Allogeneic bone marrow derived stem cells | Chondrogen | Arthritis (Phase II) | ||

| Pharmicell | Seoul, SOUTH KOREA | Autologous bone marrow derived stem cells | Hearticellgram | Acute myocardial infarction (KFDA approved), acute ischemic stroke (Phase III), chronic spinal cord injury (Phase II/III) |

| Proneuron Biotechnologies | Los Angeles, CA | Autologous bone marrow derived macrophages | ProCord | Acute complete spinal cord injury (PhaseII/III) |

| Stem Cells Inc | Palo Alto, CA | Allogeneic central nervous system derived stem cells | HuCNS-SC® | Spinal cord injury (Phase I/II), Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (Phase I complete), |

| Stemedica Cell Technologies | San Diego, CA | Allogeneic bone marrow derived stem cells | Ischemic stroke (Phase I/II) | |

| Stempeutics | Bangalore, INDIA | Allogeneic bone marrow derived stem cells | Acute myocardial infarction (Phase I/II) | |

| TiGenix | Leuven, BELGIUM | Allogenic expanded adipose derived stem cells | Cx601, Cx602, Cx611, Cx621 | Crohn’s disease (Phase II complete), intestinal bowel disease (Pre-clinical), rhuematoid arthritis (Phase II), autoimmune disease (Phase I) |

| VetCell | London, ENG UK | Autologous bone marrow derived stem cells | StemRegen | Equine digital flexor tendon strain |

The ratio of allogeneic to autologous cell products is about 2 to 1. Half of the listed products in development are derived from bone marrow. To date, no stem cell-based human therapy has completed the necessary pivotal human trials for product registration in the U.S.; Pharmicell has the first Korean FDA-approved product for acute MI treatment.

3.1. Your brain on HA

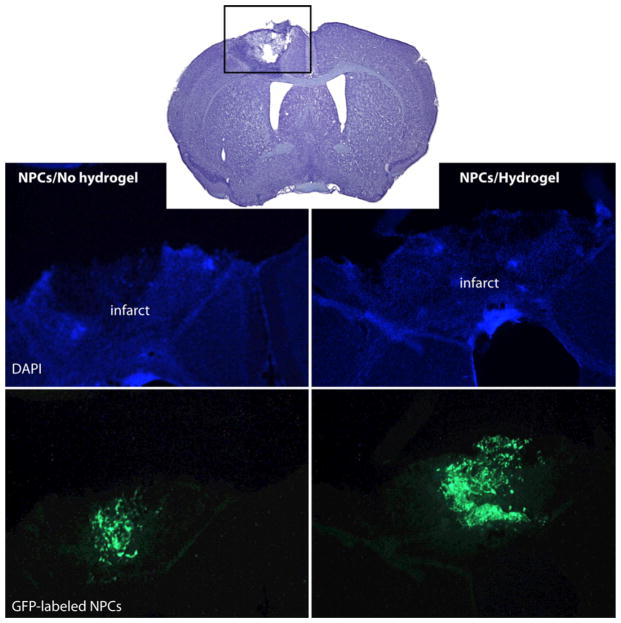

By combining therapeutic cells with an sECM consisting of co-crosslinked HA, heparin, and gelatin, the Carmichael team at UCLA improved the survival of two neural progenitor cell (NPC) lines in vitro under conditions of stress, and in vivo delivery into the cavity of a stroke-infarcted brain [14]. In addition to increased cell survival (Fig. 2), glial scar formation was reduced, and local inflammation was minimized for HyStem®-delivered cells in comparison to NPCs delivered in buffer only. Thus, stem cell transplantation into the infarct cavity within has therapeutic potential for stroke treatment [14]. In a separate model, axonal sprouting after stroke was enhanced by delivery of Lingo1, an antagonist protein, encapsulated in the same sECM in the peri-infarct cavity [15].

Fig. 2.

Encapsulation of murine NPCs in HyStem® (Hydrogel) increases viability (shown), reduces scarring and increases neuronal connections following injection into a stroke-infarcted brain [14]. (Reproduced with permission from Adv. Mater.)

3.2. Fixing the filtration system

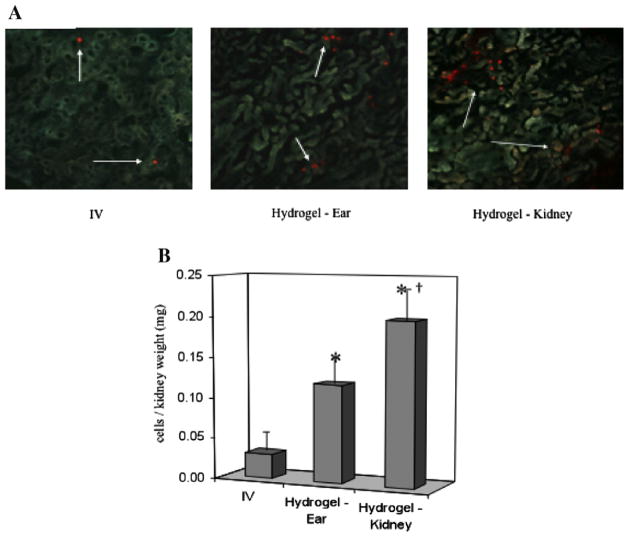

The Goligorsky team at the New York Medical College encapsulated murine embryonic endothelial progenitor cells (eEPC) in the sECM HyStem®-C to create a bioartificial stem cell niche [16,17]. Implantation of the eEPC-hydrogel into the ears of mice with drug-induced nephropathy or renal ischemia allowed hyaluronidase (HAse)-mediated eEPC mobilization to injured kidneys and improved renal function. HA hydrogels with eEPCs supported renal regeneration in ischemic and cytotoxic nephropathy, and promoted neovascularization in an ischemic hind limb model [16]. In a separate study, the Goligorsky team demonstrated that eEPCs in the same sECM reduced tissue damage and promoted kidney repair following a lipopolysaccharide challenge to induce endotoxemia in mice [18]. After 2 months, unchallenged controls were compared with sECM only, cells injected intravenously (i.v.), cells injected in the sECM subcapsularly in the kidney (endogenous HAse present) and cells injected into the ear pinna with exogenous HAse added. Both i.v. eEPCs and HyStem®-encapsulated gels significantly reduced renal fibrosis and increased renal blood flow; the renal capsule implantation and pinna implantation were not significantly different for these outcomes. Most importantly, eEPC engraftment in the kidneys (relative to i.v. injection) was 10-fold greater for capsule implantation and 6-fold greater for pinna implantation (Fig. 3) [18]. Since engraftment is the key to long-term therapeutic benefit, these support the use of an HA-based sECM as a cell delivery and retention device in the clinic.

Fig. 3.

Engraftment of murine EPCs is significantly enhanced by implantation in HyStem® (Hydrogel) as compared to i.v. injection [18]. Moreover, engraftment is significantly greater following implantation in the renal capsule compare to implantation, with co-administration of hyaluronidase, into the ear pinna. (Reproduced with permission from Am. J. Physiol.-Renal Physiol.)

3.3. Lola’s little liver gels

Human liver progenitor cells are exquisitely sensitive to both the mechanics and biochemistry of the matrix they are cultured in or on. Recent work from the Reid group at the University of North Carolina shows that human hepatic stem cells (hHpSC) in vivo are partnered with mesenchymal precursors and reside in regulated microenvironments rich in HA [10]. The in vivo hHpSC niche is modeled in vitro by growing hHpSC in three dimensions by embedding them in the HA-based hydrogel HyStem® hydrogels together with a serum-free medium for endodermal stem/progenitors. The resulting HA hydrogels, which supported cell attachment, survival and expansion of hHpSC colonies, induced transition of hHpSC colonies towards stable heterogeneous populations of hepatic progenitors depending on the stiffness of the hydrogel, showing that mechanical properties of the microenvironment can regulate differentiation in endodermal stem cell populations. Importantly, human fetal liver progenitor cells also retained a functional phenotype in three-dimensional (3-D) culture, producing significantly lower alpha-fetoprotein and significantly greater EpCAM (a tight junction marker) and albumin production than in a 2-D culture on plastic [19].

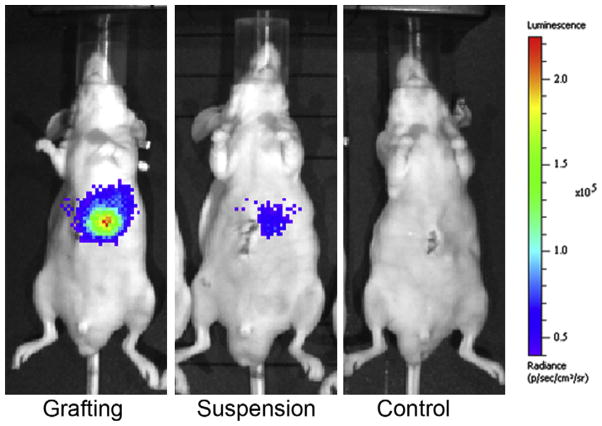

The Reid group conducted grafting experiments in immune-competent and immune-compromised mice [19]. With the immune- competent C57/BL6 mice, syngeneic murine hepatic progenitor cells (1,500,000 cells) tagged with luciferase were injected into the liver lobes in either buffer suspension or as a partially gelled slurry in the same HA-based sECM hydrogel. Intravital imaging showed that the cells injected in buffer were >99% gone after just 72 h. In contrast, some 5–10% of cells had engrafted and were present in the liver of mice injected with the HA hydrogel-encapsulated hepatic progenitors after 2 weeks. In a second experiment (Fig. 4), superior engraftment was also observed following injection of HyStem®-encapsulated human fetal hepatic progenitor cells (engineered to express luciferase) into immune-compromised SCID mouse livers. While mice receiving 1,500,000 cells in buffer showed essentially no engraftment after 72 h, nearly 35% of the HA hydrogel-encapsulated cells were still present after that time. Moreover, histological examination showed the production of human serum albumin (HSA) in the engrafted livers in mice for the HA hydrogel-encapsulated cells, but no evidence for HSA in the buffer suspended cell injections [19].

Fig. 4.

HyStem® increases engraftment of luciferase-labeled human liver progenitors injected into the livers of SCID mice [19]. The panels illustrate images recorded 48 h after cell delivery by encapsulation (grafting) in HyStem® (left), by injection as a suspension in buffer (middle), or in an uninjected control (right). Images were provided by Drs. Rachael Turner and Lola Reid, University of North Carolina.

3.4. Mending a broken heart

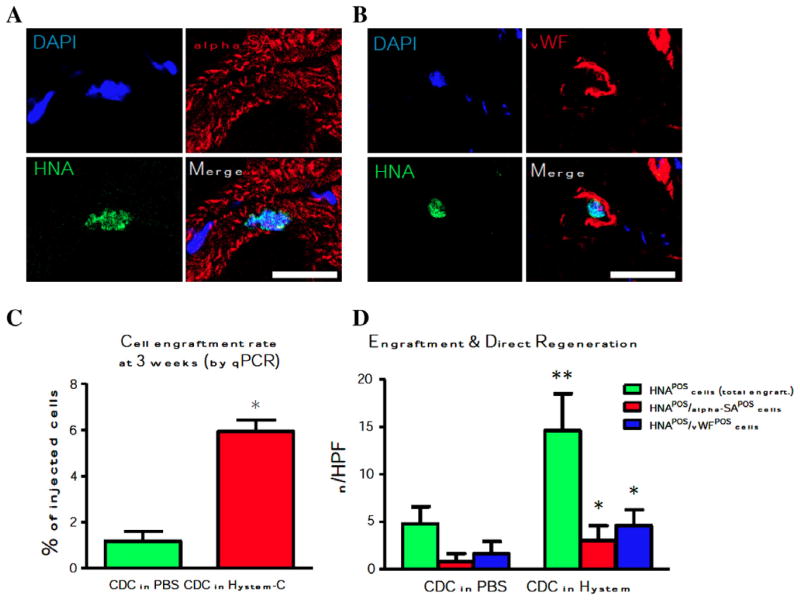

Delivery of cardiosphere-derived cells (CDC) obtained from a human adult cardiac biopsy into the periphery of infarcted heart tissue has been pioneered by the Marban team at Cedars Sinai Hospital in collaboration with Capricor, Inc. and BioTime, Inc. [20]. Injection of 150,000 CDCs in the HA-based sECM HyStem®-C (at multiple sites at the infarct edge of SCID mice) significantly increased the left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) at 3 weeks post-infarct when compared with (i) cells in buffer, (ii) the sECM alone or (iii) untreated controls. In addition, the CDC + sECM treatment showed a synergistic increase in viable tissue and wall thickness relative to cells alone or hydrogel alone. The same synergistic effect was observed for smooth muscle actin positive vasculature as a marker for increased angiogenesis. Most importantly, the CDC + sECM treatment showed 6% engraftment of injected CDCs at 3 weeks, compared to 1% engraftment for CDCs in buffer (Fig. 5) [20]. Importantly, the increase in cell number occurred in parallel with direct regeneration by newly formed cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells.

Fig. 5.

Long-term engraftment of adult human cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs) delivered in HyStem-C™, 3 weeks after injection into the hearts of SCID mice [20]. Representative confocal images for differentiation into cardiac (Panel A) and endothelial (Panel B) cells. Panel C shows increased engraftment of CDCs relative to injection of cells in buffer. Panel D shows that transplanted CDCs were positive for human nuclei antigen (HNA, green bar), and the engraftment superiority further results in more newly-formed cardiomyocytes (red bar) and endothelial cells (blue bar). (Reproduced with permission from Biomaterials.)

3.5. Good vibrations and no GAGging

Treatment of vocal fold injuries and prevention of vocal fold scarring were original drivers for the development of the injectable HA-based sECM technology [21], because of the large amount of viscoelastic HA in this tissue. First, compared to surgical implantation of fat and Teflon suspensions and scar lysis procedures, injection of an HA-based hydrogel could minimize the degree of mucosal violation and the foreign body response. This prophylactic approach using a modified HA derivative is being jointly pursued by the authors together with the Thibeault team at the University of Wisconsin. Second, HA hydrogel injections can be performed as in-office procedures under local anesthetic, increasing patient access to treatment. Third, an injected HA hydrogel would conform to the complex vocal fold dimensions, further minimizing biomechanical interruption during vibration. Because the hydrogel adheres to the tissue during gelation, the resulting mechanical interlocking strengthens the tissue–hydrogel interface. Finally, cell delivery in an HA-based sECM could lead to regeneration of vocal fold tissues. Using autologous or allogeneic hMSCs, this is the holy grail for vocal fold repair.

When human vocal fold fibroblasts were cultured in the HA-based sECM HyStem®-C, reduced collagen type 1 expression and increased fibronectin expression was observed compared to cells cultured in Matrigel (3-D) [22]. In a rabbit model, delivery of bone marrow-derived MSCs in HyStem®-C facilitated the repair of vocal fold scarring [23]. The restorative effects of MSCs were enhanced when delivered in the HA-rich sECM when compared to cells delivered in buffer, or with injection of the HA-hydrogel alone. In addition, the combination MSC + sECM therapy showed enhanced expression levels of fibronectin, procollagen 3 and TGFβ-1.

4. Challenges – don’t get lost in translation!

4.1. Regulatory challenges for cell therapy

For many emerging cell-based therapies, a scaffold or matrix will be required to deliver the cells, retain them at the desired location and maintain a hydrated 3-D niche that cells can remodel. Within this 3-D hydrogel, cells proliferate and regenerate new tissue. Since these delivery vehicles will be permanently implanted in the body, scaffold and matrices are typically classified by the U.S. Food and Drug Adminstration (FDA) as Class III medical devices requiring Premarket Approval by the Center for Devices and Radio-logic Health (CDRH) (21 CFR, 860.93; 21 U.S.C., 360c (c)(2)(C)). However, when therapeutic cells are combined with a delivery matrix or scaffold for implantation in the body, this product is classified as a combination product. In such a product, the matrix or scaffold is a medical device and the cells are considered the new therapeutic agent. As a result, such combination cell-based products are regulated by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) of the FDA, in consultation with the CDRH. These combination products follow the more traditional biological regulatory approval pathway. Final approval by CBER will be for a specific delivery matrix and specified cell type for a clearly defined indication. As a result, there is no pathway, at this time, for approval of a matrix or scaffold as a medical device for general-use in vivo cell delivery for stem cell therapy applications.

From the cellular standpoint, the regulatory paths for somatic cells and tissues and for stem cells are similar, since the former serves as the basis for the latter. Since 1993, the FDA has been developing guidelines and regulatory pathways to regulate the development, manufacture and distribution of somatic cell therapy products. Over the last decade, these guidelines have been broadened to include stem and progenitor cell therapeutic products. The guidelines are designed to ensure that such products meet defined safety requirements and have the same identity, strength, quality and purity characteristics as those represented to the FDA. Moreover, the FDA has recently mandated that any procedure in which human cells are manipulated for clinical use is subject to federal manufacturing standards and oversight (18 21 C.F.R. § 1271.3(d) (2009); see 42 U.S.C. § 264). Specifically, Part 1271 of Chapter 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations unifies the registration and listing system for establishments that manufacture human cells, tissues, and cellular and tissue-based products, and establishes current good tissue practices and other relevant procedures. These regulations, known as the Good Tissue Practice requirements, encompass the minimal manipulation of cells for clinical use; i.e. for processes that do not alter the biological characteristics of the cells (21 CFR Parts 16, 1270, 1271).

For procedures in which the biological nature of the cells is altered to affect a clinical outcome, termed “more than minimal manipulation”, Part 211 pharmaceutical current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) will apply, as well as relevant aspects of Parts 210, 600 and 1271. In addition to these base requirements, any cell-based product that contains stem cells or tissues that are highly processed, are used for other than their normal function, are combined with non-tissue components or are used for metabolic purposes would also be subject to the Public Health Safety Act, Section 351, which regulates the licensing of biological products and requires the submission of an investigational new drug application (IND) to the FDA before studies involving humans can begin (21 C.F.R. Part 312 (2009)).

If the delivery device part for a cell-based combination product has not been previously approved or cleared specifically for its intended use, detailed information on the device must be included in the IND submission to CBER for CDRH review. Regulatory review of the device component will include chemistry, manufacturing, and controls to assure compliance with cGMP manufacturing requirements. Biocompatibility of the device alone must be assessed through the prescribed in vitro and in vivo animal testing asset set forth in the ISO-10993 guidelines. These tests encompass cytotoxicity, sensitization, irritation, acute and chronic systemic toxicity, genotoxicity, and long-term implant with histopathology. In addition to data demonstrating biocompatibility and safety individually for the device and cell components, CBER will require long-term safety and toxicity studies of the device and cell combination in relevant animal models.

Cell therapy is finally becoming “mainstream” as a regenerative medicine modality [24]. Between 1998 and 2010, over 675,000 therapeutic units of cell products were manufactured and over 323,000 patients were treated. During that period, industry expert analysts estimated the market value of FDA or European-approved cell therapies to be $100–200 M. These included autologous and allogeneic products, but none of the products reported for this period were cell–biomaterial combination products [24]. Indeed, cell delivery and retention is the next frontier for regenerative medicine and tissue engineering, a field that for too long has over-promised and under-delivered [25].

4.2. Reduce business development challenges: work with academic partners

A critical driver for the long-term value of a clinical sECM platform comes from academic partnering. In particular, HyStem® has been validated by academic collaborations whose cell-based therapies are improved after combining it with the hydrogel prior to implantation. These customer-collaborators are often physicians who are passionately interested in delivering therapeutic cells to their patients in need of treatment. What constitutes a high-quality academic partnership? Typical measures of an academic partner begin with evaluating the cell-based technology according traditional metrics: (i) the complexity of the intellectual property landscape, (ii) the cost of cell manufacturing pursuant to cGMP, (iii) the difficulty of the regulatory path and (iv) reimbursement by third-party insurers. It is equally important to evaluate and actively develop the quality of the relationship with the academic partner, who becomes an integral part of the product development team. The ideal academic partner would have a fiscally sound grant support base, strong scientific productivity, a strong translational focus and a desire to partner with industry to accomplish the translation to the clinic.

Strong translational focus and ease in working with one another provide the momentum required to complete a very difficult and long road to the clinic. Distractions for pursuing other projects and tensions during difficult parts of the collaboration can be minimized during partnering discussions. Translational focus measures include the availability and frequent usage of appropriate animal models; without such model systems in place, an academic laboratory could never make the leap to clinical trials. Principal investigators who can appreciate the patient problem intimately from clinical work are often the most committed to finding a remedy to the unmet need. Finally, ease of working with one another is vital to the success of the collaboration since it reflects deep respect for each other and for the progression of the project. When both partners make time, amidst chaotic schedules, to work through rough spots, whether in person or telephonically, the relationship matures and the progress of project accelerates.

5. The translational imperative

To produce a clinical product that recreates the native ECM environment, one must optimize the biological, chemical and practical design parameters. One must also incorporate the importance of the financial, production and regulatory constraints at the beginning of the technology development, and constantly re-evaluate the suitability of the technology for clinical use during the product development. Importantly, by basing decisions on the needs of the end-users, the crucial and limiting pragmatic factors become as important as the technical details of the product.

The translational imperative for a clinical biomaterial is summarized in six words: Embrace Complexity; Engineer Versatility; Deliver Simplicity [2]. First, the complex biological challenge of rebuilding tissues from cells cannot be replicated; we should simply enable biology to do the heavy lifting. Embracing the biological complexity can result in a solution that is elegant in its simplicity. Second, a single formulation cannot fulfill every need, from treating an ischemic brain to repairing a scarred vocal fold. Thus, the solution is to engineer compositional flexibility, both mechanical and biochemical, so that a portfolio of products based on a small number of approved components can be assembled in different forms for use by physicians performing cell therapy for different tissues. Finally, for cell therapy to truly be translated to the clinic, we must deliver simplicity. The acceptance of a new technology into any market is not determined solely by improvement in patient outcome. The true limiting factors are cost, familiarity, ease of use and reimbursement. The living sECM technology achieves a balance between the physiological and practical requirements, and the entry of these products into the clinic has the potential for regenerative medicine.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH for the original basic research grant that allowed development of the sECMs (R01 DC 04336), applied research awards (SBIRs to Glycosan), the University of Utah, and the State of Utah Centers of Excellence Program for financial support. We also thank collaborators and customers for sharing their results and suggestions, and for propelling us toward addressing unmet market needs for cell therapy.

Appendix A. Figures with essential colour discrimination

Certain figures in this article, particularly Figs. 2–5, are difficult to interpret in black and white. The full colour images can be found in the on-line version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2012.06.043.

Footnotes

Part of the Special Issue “Advanced Functional Polymers in Medicine (AFPM)”, guest editors: Professors Luigi Ambrosio, Dirk W. Grijpma and Andreas Lendlein.

Disclosure

G.D.P is a consultant for BioTime; G.D.P and W.P.T were co-founders of Glycosan; I.E. T.I.Z., M.W., and W.P.T. are current employees of BioTime; all are stockholders.

References

- 1.Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Synthetic biomaterials as instructive extracellular microenvironments for morphogenesis in tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:47–55. doi: 10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prestwich GD. Engineering a clinically-useful matrix for cell therapy. Organogenesis. 2008;4:42–7. doi: 10.4161/org.6152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serban MA, Prestwich GD. Making modular extracellular matrices: solutions for the puzzle. Methods. 2008;45:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shu XZ, Liu Y, Luo Y, Roberts MC, Prestwich GD. Disulfide crosslinked hyaluronan hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:1304–11. doi: 10.1021/bm025603c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prestwich G. Hyaluronic acid-based clinical biomaterials for cell and molecule delivery in regenerative medicine. J Control Release. 2011:193–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burdick J, Prestwich G. Hyaluronic acid hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv Mater. 2011;23:H41–56. doi: 10.1002/adma.201003963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prestwich GD. Evaluating drug efficacy and toxicology in three dimensions: using synthetic extracellular matrices in drug discovery. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:139–48. doi: 10.1021/ar7000827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bollyky P, Wua R, Falka B, Lorda J, Longa S, Preisingera A, et al. ECM components guide IL-10 producing regulatory T-cell (TR1) induction from effector memory T-cell precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:7938–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017360108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanderhooft JL, Alcoutlabi M, Magda JJ, Prestwich GD. Rheological properties of cross-linked hyaluronan–gelatin hydrogels for tissue engineering. Macromol Biosci. 2009;9:20–8. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200800141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lozoya O, Wauthier E, Turner R, Barbier C, Prestwich GD, Guilak F, et al. Mechanical stiffness of the microenvironment regulates hepatic stem/progenitors in experimental models of the stem cell niche of the human liver. Biomaterials. 2011;32:7389–402. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanjaya-Putra D, Yee J, Ceci D, Truitt R, Yee D, Gerecht S. Vascular endothelial growth factor and substrate mechanics regulate in vitro tubulogenesis of endothelial progenitor cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;14:2436–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00981.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chopra A, Lin V, McCollough A, Atzet S, Prestwich GD, Wechsler AS, et al. Reprogramming cardiomyocyte mechanosensing by crosstalk between integrins and hyaluronic acid receptors. J Biomech. 2012;45:824–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zarembinski T, Tew W, Atzet S. The use of a hydrogel matrix as a cellular delivery vehicle in future cell-based therapies: biological and non-biological considerations. In: Eberli D, editor. Regenerative medicine and tissue engineering – cells and biomaterials. InTech; 2011. pp. 341–64. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhong J, Chan A, Morad L, Kornblum HI, Fan G, Carmichael ST. Hydrogel matrix to support stem cell survival after brain transplantation in stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24:636–44. doi: 10.1177/1545968310361958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li S, Overman J, Katsman D, Kozlov S, Donnelly C, Twiss J, et al. An age-related sprouting transcriptome provides molecular control of axonal sprouting after stroke. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1496–504. doi: 10.1038/nn.2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ratliff B, Ghaly T, Brudnicki P, Yasuda K, Rajdev M, Bank M, et al. Endothelial progenitors encapsulated in bioartifical niches are insulated from systemic cytotoxicity and are angiogenesis competent. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299:F178–86. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00102.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prestwich GD, Ghaly T, Brudnicki P, Ratliff B, Goligorsky MS. Bioartificial Stem cell niches: engineering a regenerative microenvironment. In: Goligorsky MS, editor. Regenerative nephrology. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2011. pp. 245–56. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghaly T, Rabadi M, Weber M, Rabadi S, Bank M, Grom J, et al. Hydrogel-embedded endothelial progenitor cells evade LPS and mitigateendotoxemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;301:F802–12. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00124.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner R, Wauthier E, Lozoya O, McClelland R, Bowsher J, Barbier C, et al. Successful transplantation of human hepatic stem cells and with restricted localization to liver using hyaluronan grafts. Unpublished results. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng K, Blusztajn A, Shen D, Li T, Sun B, Galang G, et al. Enhanced engraftment and therapeutic benefit of human cardiosphere-derived cells delivered in an in situ polymerizable hydrogel. Biomaterials. 2012;33:5317–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartlett R, Prestwich GD, Thibeault SL. Therapeutic potential of gel-based injectables for vocal fold regeneration. Biomed Mater. 2012;7:024103. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/7/2/024103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson B, Fox R, Chen X, Thibeault S. Tissue regeneration of the vocal fold using bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and synthetic extracellular matrix injections in rats. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:537–45. doi: 10.1002/lary.20782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duflo S, Thibeault SL, Li W, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD. Vocal fold tissue repair in vivo using a synthetic extracellular matrix. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2171–80. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mason C, Manzotti E. Regenerative medicine cell therapies: numbers of units manufactured and patients treated between 1988 and 2010. Regen Med. 2010;5:307–13. doi: 10.2217/rme.10.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nerem RM. Tissue engineering: the hope, the hype, and the future. Tissue Eng. 2005;12:1143–50. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]