Abstract

A highly torquoselective thermal triene 6π electrocyclization controls the relative stereochemistry between the C3 and C18 stereocenters of the dodecahydroindolo[2,3-a]benzo[g]quinolizine skeleton of reserpine-type alkaloids. Employing a tandem cross-coupling/electrocyclization protocol allowed us to form the requisite triene and ensure its subsequent cyclization. A novel low-temperature dibromoketene acetal Claisen rearrangement established the requisite exocyclic dienylbromide precursor for the palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction.

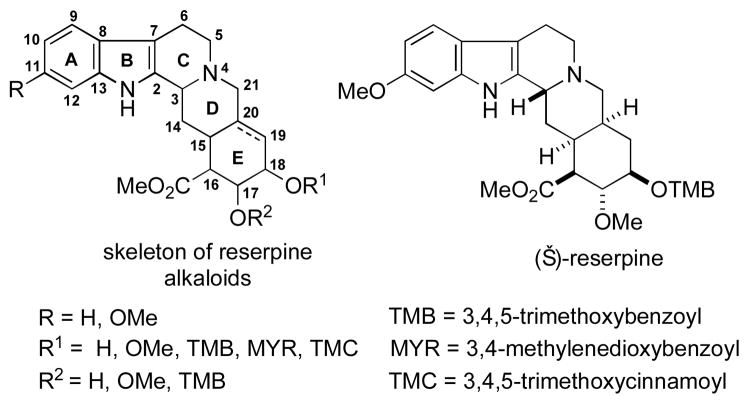

The reserpine-type alkaloids, possessing the dodecahydroindolo[2,3-a]benzo[g]quinolizine skeleton, are the most structurally complex of the indole alkaloids (Figure 1). These compounds exhibit significant CNS activity and are key components of herbal medicines that have been used for centuries. Sixteen naturally occurring reserpine alkaloids have been isolated; among them, several have been prepared, along with a variety of semi-synthetic derivatives.1,2 The most common synthetic strategies toward reserpine alkaloids are “bottom-up” approaches, involving preparation of the fused D/E ring system with subsequent installation of the C3 stereocenter in the process of C2–C3 bond formation.3a–h “Top-down” approaches, involving either C3–C14 or C14–C15 bond formation with concomitant generation of the C3 stereocenter and establishment of the C15 and C20 stereocenters, have been employed less frequently.3i–l

Figure 1.

Reserpine-type alkaloids.

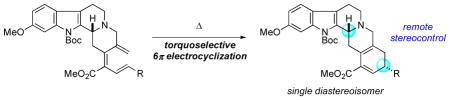

As an alternative to these strategies, we were intrigued by the idea of the C3 center exerting remote stereocontrol across the fused D/E ring system during the formation of the C18 stereocenter. Because C18 is the most remote stereocenter from C3 on the benzo[g]quinolizine scaffold, we were aware of the potential difficulty of this 1,6-relay of stereochemical information and sought to identify an appropriate reaction manifold for such a strategy.

The thermal 6π electrocyclization of all-carbon–containing trienes is an underutilized, yet highly powerful, reaction with the capacity to generate two new stereocenters. Furthermore, if the starting triene possesses a stereogenic center, the newly generated stereocenters could be formed in a highly diastereoselective manner. Nevertheless, the electrocyclization of all-carbon trienes has received relatively little attention in the synthesis of small molecules when compared with other pericyclic reactions, such as the Diels–Alder and Claisen reactions.4

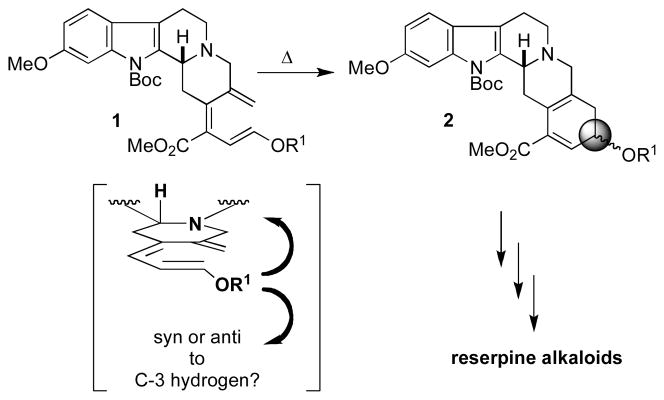

As a part of our growing interest in novel 6π electrocyclizations5 and a research program in nucleophilic phosphine catalysis for the synthesis of heterocycles and carbocycles,6 we became interested in the potential of these transformations to meet the goals of our synthetic strategy for remote 1,6-stereoinduction. We envisioned that the presence of the C3 stereocenter would allow the C18 stereocenter to be formed in a stereocontrolled manner through a torquoselective 6π electrocyclization (Scheme 1). This unique approach stands in stark contrast to previous synthetic strategies toward the synthesis of reserpine alkaloids and hinges upon a seldom-explored remote 1,6-stereoselective 6π electrocyclization.4d

Scheme 1.

Remote Stereochemical Induction via Thermal Torquoselective 6π Electrocyclization

Although the literature does not offer an extensive discussion of remote stereocontrol in the context of 6π electrocyclization, we reasoned that a suitably constrained scaffold, such as that of the triene 1, should allow the C3 stereocenter to influence the stereoselectivity of this transformation (Scheme 1).4b While optimistic for the possibility of stereochemical control, we lacked any established models to predict the diastereoisomer favored upon electrocyclization. If successful, however, this synthetic strategy would provide the pentacycle 2 possessing the requisite ABCDE skeleton in a stereodefined manner. Upon removal of R1, the exposed hydroxyl functionality could be inverted readily, if necessary, and the resultant α,β-unsaturated ester contained in the E ring could act as a handle for elaboration to (±)-reserpine and related alkaloids.

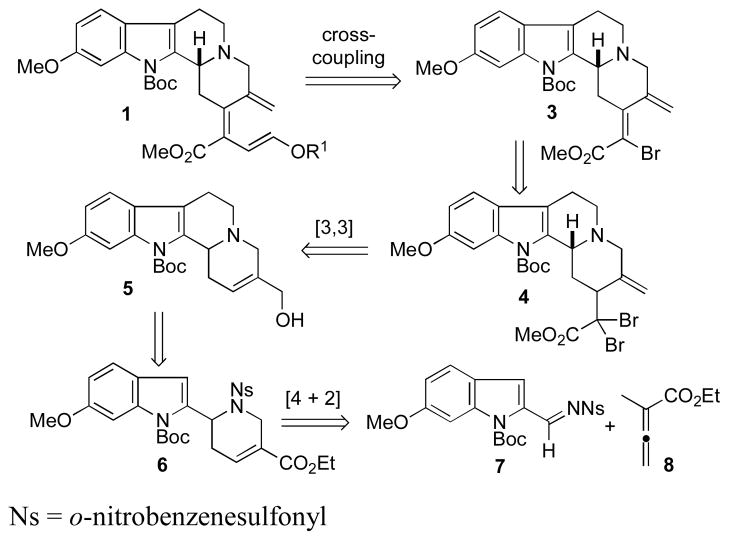

We envisioned efficient access to 1 through cross-coupling of a suitable pseudo-metal with the vinyl bromide 3, which could be derived from the appropriately functionalized ester 4 (Scheme 2). We planned to generate the α,α-dihaloester 4 from the allylic alcohol 5 through [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of the corresponding dihaloketene acetal. Based upon our previous experience with heterocycle formation through phosphine catalysis, we expected a relatively straightforward elaboration of the allylic alcohol 5 from the [4 + 2] annulation product 6.6b

Scheme 2.

Reterosynthesis of the Key Triene 1

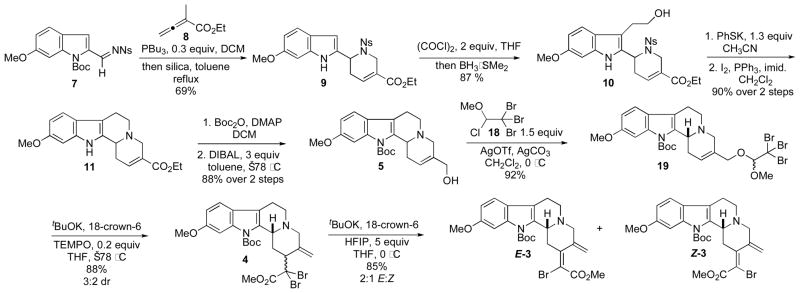

The [4 + 2] annulation between the imine 7 and the butadienoate 8 in the presence of catalytic PBu3 proceeded uneventfully (Scheme 3);7 we isolated the tetrahydropyridine 9 as a yellow crystalline solid after removal of the Boc group in toluene under reflux in the presence of silica gel. Next, in a one-pot procedure, we prepared the tryptophol 10 through treatment of the indole 9 with oxalyl chloride at ambient temperature and subsequent BH3·SMe2-mediated reduction of the intermediate glyoxylic acid chloride. The use of bases commonly employed under classical Fukuyama conditions for nosyl deprotection led to partial decomposition of 10 and low yields. We found, however, that addition of potassium thiophenoxide (PhSK) as a preformed salt led to clean removal of the o-nosyl protecting group in excellent yield. Formation of ring C in 11 was facilitated by the intramolecular alkylation of the resulting secondary amine in the presence of PPh3 and I2. Protection of the indole nitrogen atom with Boc2O and subsequent DIBAL-mediated reduction of the ester gave the key allylic alcohol 5 in 88% yield. Overall, this route provided efficient access to 5 in eight steps from the imine 7 on a multigram scale.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of the Cross-Coupling Partner 3 Through Phosphine-Catalyzed [4 + 2] Annulation and Dibromoketene Acetal Claisen Rearrangement.

We prepared a variety of dimethylorthoacetates containing α-halogen atoms with the intention of exploiting a Johnson–Claisen rearrangement for the preparation of the α,α-dibromoester 4.8 Despite our best efforts, we were unable to facilitate the desired [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement employing these substituted orthoesters.9 Fortunately, access to 4 could be achieved through [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of the dibromoketene acetal generated through dehydrobromination of the acetal 19.10 Remarkably, rearrangement occurred spontaneously after elimination of HBr at −78 °C, providing the desired α,α-dibromoester 4 in 88% yield. To the best of our knowledge, this example is the first [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement leading directly to highly functionalized α,α-dibromoesters.11 A number of amine and alkoxide bases facilitated β-elimination from the α,α-dibromoester 4 to give the vinyl bromides 3 in approximately a 2:1 dr, but with very low mass recoveries (<40%). Ultimately, we found that potassium hexafluoroisopropoxide, prepared in situ through the addition of 1 M tBuOK to a solution of excess hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) and [18]crown-6 at 0 °C, cleanly afforded the vinyl bromides E-3 and Z-3 as a separable 2:1 mixture in 85% yield.12

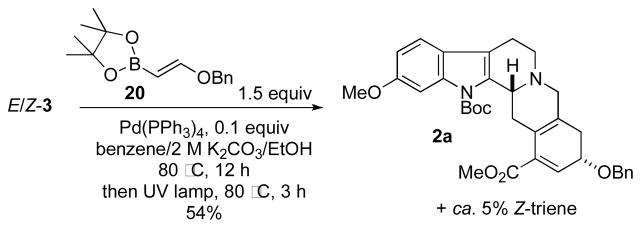

For the formation of the requisite triene 1 for our planned 6π electrocyclization, we initially speculated that only Z-3 would be suitable for stereospecific cross-coupling reaction to form the E-triene 1. We found, however, that we could employ both isomers under an optimized sequence of Suzuki cross-coupling, photochemical isomerization of the undesired triene, and electrocyclization at 80 °C in benzene.13 Following this protocol, we obtained the desired pentacycle in 54% yield as a single diastereoisomer, starting from a mixture of the two vinyl bromides E/Z-3. X-ray crystallographic analysis revealed the relative configuration of 2a. We suspect that the reaction selectivity arises from an allylic interaction between the methyl ester group and the adjacent D-ring methylene unit in the transition state.4a,e Such interactions can be sufficiently large to provide high levels of stereocontrol; studies are currently ongoing in our laboratories to fully assess the controlling element in this reaction.

Although we could functionalize 2a through conjugate addition to the α,β-unsaturated ester, the yields and diastereoselectivities of these reactions were generally very poor, providing all four possible diastereoisomers. We reasoned that deprotection of the benzyl group would allow a hydroxyl-directed reaction to provide better control over the stereoselectivity. Unfortunately, our efforts at removing this protecting group under a variety of conditions gave undesired products, including those from reduction of the α,β-unsaturated ester and elimination of the benzyloxy substituent resulting in aromatization of the E ring. Considering the difficulty we encountered installing the requisite functionality onto 2a, we sought to install all of the E-ring alkoxy groups of reserpine in a single step through our tandem cross-coupling/ 6π electrocyclization. We envisioned that this approach would require a 1,2-dialkoxyvinyl pseudo-metal to undergo the cross-coupling reaction. From an exploration of the literature, we identified the dioxole 21 as a potentially suitable candidate (Scheme 5).14

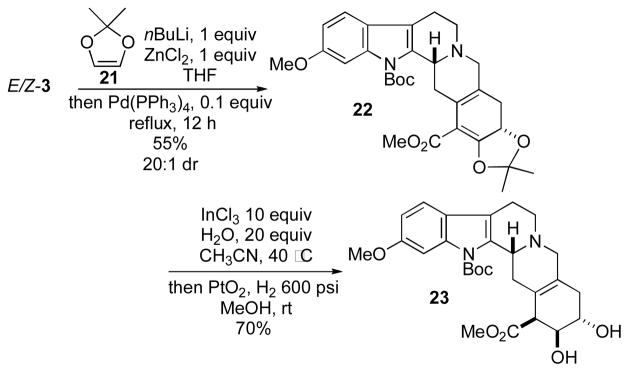

Scheme 5.

Torquoselective Negishi/6π Electrocyclization

Although the conversion of 21 into a variety of vinyl boronic esters (including pinacol and diisopropyl) proceeded well, their instability during purification limited our options for optimization of the Suzuki/6π electrocyclization cascade. Instead, following treatment of 21 with nBuLi and exposure to anhydrous ZnCl2, we could facilitate a Negishi/6π electrocyclization cascade upon heating E/Z-3 under reflux in THF in the presence of Pd(PPh3)4. To the best of our knowledge, this transformation marks the first use of the dioxole 21 as a highly oxidized partner in cross-coupling chemistry. The optimized conditions provided the acetonide 22 as the sole product in 55% yield and 20:1 dr. Surprisingly, photoisomerization was unnecessary in this case: we obtained the cyclization product in similar yield directly from the cross-coupling reaction.15

Deprotection of the acetonide with InCl3 and water in MeCN provided an oxidatively sensitive and unstable hydroxy ketoester.16 Reduction of the ketone under H2 in the presence of PtO2 provided the trans diol 23 in 70% yield as a single diastereoisomer. Advancing the diol 23 to (±)-reserpine would require selective benzoylation of the α-hydroxyl group, deprotection of the Boc group, reduction (from the α face) of the olefinic bond at the D/E ring junction,18 inversion of the relative configuration of the vicinal diol through a benzoate walk,19 and O-methylation.

In conclusion, we have obtained highly functionalized pentacyclic intermediates en route to the preparation of reserpine-type alkaloids. Our synthetic sequence relies on a phosphine-catalyzed [4 + 2] annulation, a novel dibromoketene acetal Claisen rearrangement, and a cross-coupling/ torquoselective 6π electrocyclization cascade. In particular, we have demonstrated that the torquoselective triene 6π electrocyclization is an extremely efficient method for remote 1,6-transfer of chirality from C3 to C18 in the synthesis of reserpine alkaloids. We are currently assessing the stereochemistry-controlling elements in these reactions and their potential for further synthetic applications.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 4.

Torquoselective Suzuki/6π Electrocyclization

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the NIH (R01GM071779 and P41GM081282) and the NSF (equipment grant CHE-1048804). We thank Christian Bustillos for support in the preparation of synthetic intermediates and Prof. Hongchao Guo (China Agricultural University) for providing the allenoate 8 (synthesized in the National Key Technologies R&D Program of China, 2012BAK25B03, CAU).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures; characterization data; copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra; crystallographic data for 2a and Z-3 (CIF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pub.acs.org.

References

- 1.Szantay C, Blasko G, Honty K, Dornyei G. In: The Alkaloids Chemistry and Pharmacology. Brossi A, editor. Vol. 27. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1986. Chapter 2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Chen FE, Huang J. Chem Rev. 2005;105:4671. doi: 10.1021/cr050521a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Healy D, Savage M. Br J Psychiat. 1998;172:376. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.5.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bleuler M, Stoll WA. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1955;61:167. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1955.tb42463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Woodward RB, Bader FE, Bickel H, Frey AJ, Kierstead RW. J Am Chem Soc. 1956;78:2023. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pearlman BA. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:6404. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wender PA, Schaus JM, White AW. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:6157. [Google Scholar]; (d) Martin SF, Grzejszczak S, Rueeger H, Williamson SA. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:4072. [Google Scholar]; (e) Stork G. Pure Appl Chem. 1989;61:439. [Google Scholar]; (f) Baxter EW, Labaree D, Ammon HL, Mariano PS. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:7682. [Google Scholar]; (g) Gomez AM, Lopez C, Fraser-Reid B. J Org Chem. 1995;60:3859. [Google Scholar]; (h) Hanessian S, Pan J, Carnell A, Bouchard H, Lesage L. J Org Chem. 1997;62:465. doi: 10.1021/jo961713w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Beke D, Szantay C. Chem Ber. 1962;95:2132. [Google Scholar]; (j) Szantay C, Toke L. Tetrahedron Lett. 1963;4:251. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4039(00)90106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Szantay C, Toke L, Kalaus G. J Org Chem. 1967;32:423. [Google Scholar]; (l) Naito T, Hirata Y, Miyata O, Ninomiya I, Inoue M, Kamiichi K, Doi M. Chem Pharm Bull. 1989;37:901. [Google Scholar]

- 4.For notable early examples of thermal torquoselective all-carbon 6π electrocyclizations, see: Trost BM, Shi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:791.Dauben WG, Williams RG, McKelvey RD. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:3932. doi: 10.1021/ja00793a018.Corey EJ, Hortmann AG. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;85:4033. doi: 10.1021/ja00952a037.For recent examples, see: Hayashi R, Walton MC, Hsung RP, Schwab JH, Yu X. Org Lett. 2010;12:5768. doi: 10.1021/ol102693e.Jung ME, Min SJ. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:3682.Benson CL, West FG. Org Lett. 2007;9:2545. doi: 10.1021/ol070924s.Sunnemann HW, de Meijere A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:895. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352162.For recent examples of all-carbon 6π electrocyclizations of achiral molecules, see: Togeum SMT, Hussain M, Malik I, Villinger A, Langer P. Tetahedron Lett. 2009;50:4962.Alvararez-Manzaneda E, Chahboun R, Cabrera E, Alvarez E, Haidour A, Ramos JM, Alvarez-Manzaneda R, Hmamouchi M, Es-Samti H. Chem Commun. 2009:592. doi: 10.1039/b816812a.Suffert J, Salem B, Klotz P. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:12107. doi: 10.1021/ja0170495.von Zezschwitz P, Petry F, de Meijere A. Chem Eur J. 2001;7:4035. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010917)7:18<4035::aid-chem4035>3.0.co;2-p.For a review on asymmetric electrocyclic reactions, see: Thompson S, Coyne AG, Knipe PC, Smith MD. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:4217. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15022g.For recent discussions on all-carbon 6π electrocyclizations, see: Tantillo D. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:31. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804908.Bishop LM, Barbarow JE, Bergman RB, Trauner D. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:8100. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803336.Yu TQ, Fu Y, Liu L, Guo QX. J Org Chem. 2006;71:6157. doi: 10.1021/jo060885i.

- 5.(a) Creech GS, Kwon O. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8876. doi: 10.1021/ja1038819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Henry CE, Kwon O. Org Lett. 2007;9:3069. doi: 10.1021/ol071181d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Fan YC, Kwon O. Phosphine Catalysis. Science of Synthesis [Google Scholar]; List B, editor. Lewis Base and Acid Catalysts. Vol. 1. Georg Thieme; Stuttgart: 2012. Asymmetric Organocatalysis; pp. 723–782. [Google Scholar]; (b) Villa RA, Xu Q, Kwon O. Org Lett. 2012;14:4634. doi: 10.1021/ol302077n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tran YS, Martin T, Kwon O. Chem Asian J. 2011;6:2101. doi: 10.1002/asia.201100190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Khong SN, Tran YS, Kwon O. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:4760. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lu K, Kwon O. Org Synth. 2009;86:2012. doi: 10.1002/0471264229.os086.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Sriramurthy V, Barcan GA, Kwon O. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12928. doi: 10.1021/ja073754n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Tran YS, Kwon O. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12632. doi: 10.1021/ja0752181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Tran YS, Kwon O. Org Lett. 2005;7:4289. doi: 10.1021/ol051799s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Zhu X, Lan J, Kwon O. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4716. doi: 10.1021/ja0344009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.See the Supporting Information for the synthesis of 7.

- 8.(a) Keegstra MA. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:2681. [Google Scholar]; (b) McElvain SM, Waters PM. J Am Chem Soc. 1942;64:1963. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lounasmaa M, Hanhinen P, Jokela R. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:8623. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McElvain SM, Kundiger D. Org Synth. 1943;23:45. [Google Scholar]

- 11.For examples of Claisen rearrangements of difluoro- or dichlorosubstituted vinyl ethers, leading to difluoro-esters, -ketones, and - aldehydes and dichloroaldehydes, see: Christopher A, Brandes D, Kelly S, Minehan T. Org Lett. 2006;8:451. doi: 10.1021/ol052685j.Yuan W, Berman RJ, Gelb MH. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:8071.Welch JT, Samartino JS. J Org Chem. 1985;50:3663.Metcalf BW, Jarvi ET, Burkhart JP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:2861.

- 12.The geometry of the olefin was assigned based on X-ray crystallographic analysis of Z-3 (see Supporting Information for details).

- 13.For a discussion of selective photochemical isomerization of all-carbon trienes followed by thermal 6π electrocyclization, see: von Essen R, von Zezschwitz P, Vidovic D, de Meijere A. Chem Eur J. 2004;10:4341. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400238.This sequence was ideal because the vinyl bromides E-3 and Z-3 both underwent Suzuki cross-coupling with low levels of stereospecificity, providing inseparable mixtures of 2a and the undesired triene in approximately 2:1 and 3:1 ratios, respectively.

- 14.(a) Lett R, Melnyk O. Roussel Uclaf; France: US Patent 5,723,638. 1998 Mar 3;; (b) Posner GH, Nelson TD. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:4573. [Google Scholar]

- 15.For a recent discussion of isomerization during palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, see: Ling G-P, Voigtritter KR, Cai C, Lipshutz BH. J Org Chem. 2012;77:3700. doi: 10.1021/jo300437t.and references therein.

- 16.Pfrengle F, Dekaris V, Schefzig L, Zimmer R, Reissig H-U. Synlett. 2008;19:2965. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The relative stereochemistry was assigned by NOESY 1H NMR spectroscopy of the corresponding acetonide; see the Supporting Information.

- 18.(a) Winstein S, Buckles RE. J Am Chem Soc. 1943;65:613. [Google Scholar]; (b) Buchanan JG, Edgar AR. Carbohydr Res. 1976;49:289. [Google Scholar]; (c) Jaconsen S, Mols O. Acta Chim Scand. 1981;35:169. [Google Scholar]; (d) Binkley RW, Sivik MR. J Org Chem. 1986;51:2619. [Google Scholar]; (e) Bloomfield GC, Ritchie TJ, Wriggleworth R. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1992:1229. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Lounasmaa M, Jokele R. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:615. [Google Scholar]; (b) Paivio E, Berner M, Tolvanen A, Jokela R. Heterocycles. 2000;10:2241. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.