Abstract

The efficacy of 15 nm gold nanoparticles (AuNP) coated with Yersinia pestis F1-antigen, as an immunogen in mice, has been assessed. The nanoparticles were decorated with F1-antigen using N-hydroxysuccinimide and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide coupling chemistry. Mice given AuNP-F1 in alhydrogel generated the greatest IgG antibody response to F1-antigen when compared with mice given AuNP-F1 in PBS or given unconjugated F1-antigen in PBS or alhydrogel. Compared with unconjugated F1-antigen, the IgG2a response was enhanced in mice dosed with AuNP-F1 in PBS (p < 0.05) but not in mice immunised with AuNP-F1 in alhydogel. All treatment groups developed a memory response to F1-antigen, the polarity of which was inflenced by formulation in alhydrogel. The sera raised against F1-antigen coupled to AuNPs was able to competitively bind to rF1-antigen, displacing protective macaque sera.

Keywords: Plague, Y. pestis, gold nanoparticle, vaccine, carbodiimide

Introduction

Yersinia pestis is a Gram-negative bacterium and the causative agent of plague [1]. Although the bacterium no longer causes pandemics of disease, the World Health Organisation estimates that world wide there are still approximately 3000 cases of plague annually [2]. The isolation of drug resistant strains, as well as the concern over the potential for Y. pestis to be used as a bioterrorism agent, has led to a recent resurgence in research in developing a vaccine. Immunisation with the F1-antigen, which normally encapsulates the bacterium, can provide protection against experimental plague [3–5]. Consequently, the F1-antigen is currently included in candidate plague vaccines, some of which have completed preliminary trials in humans [6–8].

The field of nanotechnology has growing applicability to medical biotechnology including drug and vaccine delivery. For example, liposomes can self-associate to form spherical micelles, typically 400 nm in diameter, with an aqueous interior [9]. Polymeric micelles, made from inert materials or biodegradable polymers such as poly-L-lactide (PLA) or poly-L-lactide-co-glycolides (PLGA) allow drug encapsulation within a hydrophobic core or absorption to the hydrophilic shell. This encapsulation processes can be manipulated to encapsulate drugs or vaccines within the interior. Encapsulation technologies have allowed otherwise toxic drugs, such as paclitaxel, to be delivered without the use of toxic solvents [10].

Also of interest for drug and vaccine delivery is the use of solid NPs, composed from a range of materials and ranging in size from 1–500 nm. Some research has used gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) since they can be easily synthesised in the laboratory to provide monodisperse particles of a predetermined size [11–13]. Subsequently the rate and mechanisms of uptake of AuNPs have been determined and 50 nm particles shown to be optimal for uptake by HeLa cells [14]. Smaller particles (< 20 nm) may be able to enter mammalian cell lines via non-endosomal pathways [15, 16]. Therefore, particles of different sizes might influence the immune response to the passenger antigen. AuNPs also allow alternate immunisation routes to be used. For example, oral or nasal administration of insulin loaded AuNPs enhanced the intestinal absorption of insulin and reduced blood glucose levels in diabetic rats to a greater extent than insulin solution alone [17, 18]. AuNPs have also been used widely for the epidermal delivery of DNA vaccines using a “gene gun” [19, 20]. Despite its low delivery efficiency, this method elicits humoral and cellular immune responses making it one of the most successful approaches to DNA vaccine delivery to date [19]. Here we describe the conjugation of Y. pestis F1-antigen onto AuNPs , in order to determine whether this delivery system will enhance immunogenicity in mice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Nanoparticle synthesis

Gold(III) chloride trihydrate (HAuCl4 · 3H2O, 99.9%), sodium citrate dihydrate (Na3C6H5O7 · 2H2O, 99%), N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N'-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS, 98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. Ltd. (Gillingham, UK).

AuNPs were synthesised using the Turkevich method [13]. Briefly, 90 ml 1mM HAuCl4.3H2O was heated to 90°C with stirring. Next, 10 ml 90 mM Na3C6H5O7 was added before cooling to room temperature in the dark. Particle characterisation was carried out using ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy and their diameters determined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

2.2 Conjugation of protein onto gold nanoparticles

Untagged recombinant F1-antigen (rF1) was produced in Escherichia coli from the expression system previously described [21], under good manufacturing practice conditions. Briefly, E. coli harbouring the caf operon were grown in L-broth and centrifuged cells re-suspended in PBS to release F1-antigen from the cell surface. The F1-antigen was purified using ammonium sulphate precipitation followed by gel filtration chromatography. The F1 antigen preparation was demonstrated to be endotoxin free. The F1-antigen was immobilised onto AuNPs using carbodiimide chemistry. To a NP suspension, 0.1 mM 16-mercaptohexadecanoic acid (MHDA) was added followed by 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton®-x 100 and incubated for 2h at room temperature. The mixture was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant removed and the pellet re-suspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC), 0.15 mM and 0.6 mM respectively were added before further adding 20 µg/ml (final concentration) F1-antigen. The solution was incubated at room temperature for 2h. Centrifugation was used to sediment the conjugated NPs which were resuspended in PBS and characterised using spectrometry.

2.3 Protein quantification

Conjugated protein was released from AuNPs using 0.1 mM mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), displacing the MHDA linker from the gold. The sample was separated through a NuPAGE® 4–12% Bis-Tris gel alongside known amounts of protein, before staining with Coomassie Blue. Densitometry was used to determine the amount of protein released from the AuNPs.

2.4 Immunisation

Groups of 5 female 6–8 week old BALB/c mice were immunized once with 0.1 ml per mouse by the intra-muscular (i.m.): group 1 received 0.93 µg rF1-antigen conjugated NPs formulated in 0.26% w/v alhydrogel (AuNP-F1/alhy); group 2 received 0.93 µg rF1-antigen conjugated NPs in PBS (AuNP-F1/PBS); group 3 received empty NPs in PBS (NP/PBS); group 4 received 0.93 µg rF1 formulated in 0.26% w/v alhydrogel (F1/alhy); and group 5 received 0.93 µg rF1 in PBS (F1/PBS). Mice were bled from the lateral tail vein each week to obtain blood for antibody analysis. Mice were euthanized after six weeks with terminal blood sampling and splenectomy.

2.5 Immunoanalysis

Sera from individual animals were assayed for F1-specific IgG titre using an enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) [22]. Briefly, sera were aliquoted into microtitre wells pre-coated with 5 µg/ml F1 (in PBS). Binding of serum was detected using an HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, anti-mouse IgG1 or anti-mouse IgG2a (Abcam; 1:5000 in 1% skimmed milk in TBS) followed by incubation (37°C, 1 h). ABTS substrate was added (Pierce) and the absorbance measured at 415 nm using a Multiskan plate reader. Titres were determined by comparison with a standard curve using Ascent software. Geometric mean titres were determined ± standard error of the mean for each treatment, allowing a statistical comparison of mean titres between groups, using the Student’s t-test.

The detection of antibody which competed with a protective polyclonal macaque serum for binding to F1-antigen was determined as previously described [6]. Briefly, F1-antigen was coated (5 µg/ml) onto microtitre plate wells followed by the addition binding of reference serum at a 1:10 dilution. Individual sera were added in duplicate in a 2-fold dilution series in 1% (w/v) skimmed milk powder in TBS. Naive macaque serum was used as a negative control. HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Abcam; 1:5000 in 1% skimmed milk in TBS) was added followed by incubation (37°C, 1h). Plates were washed prior to the addition of ABTS substrate (Pierce) with subsequent reading of the absorbance at 415 nm.

2.6 Flow cytometric analysis

Spleens from individual mice were homogenised in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium supplemented with L-glutamine, penicillin and streptomycin and the suspension splenocytes washed by centrifugation (10,000 rpm; 5 min) prior to collecting the cell pellet and re-suspending the cells in DMEM supplemented as described above, with additional 10% v/v foetal calf serum. Live splenocytes were enumerated and 200 µl of each was aliquoted in duplicate to the wells of a 96-well plate, and F1-antigen was added to each well at a final concentration of 25µg/ml. Plates were incubated overnight (37°C/5% CO2). Next day, plates were centrifuged and cell culture supernatants were collected and frozen (−80°C) pending analysis of cytokines by cytometric bead assay (Becton Dickinson, UK). Non-adherent splenocytes were removed after centrifugation, collected and stained with a mastermix of antibodies specific for surface markers CD3, CD4, CD8 and CD45, and each labelled with a different chromophore (Becton Dickinson, UK). Antibody-bound cells were analysed by fluorescence activated cells sorting (Cantifluor, Becton Dickinson, UK) and the percentage and activation status of cells in the mixed splenocyte suspension was determined.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Statistical differences between mean values were calculated using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test and p values of ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1 Preparation of gold nanoparticles

The synthesis of AuNPs used the Turkevich method of gold chloride reduction with citrate, where the diameter of the particles was controlled by the concentration of the citrate. The particles remain stable due to the repulsion of the anionic surface in the citrate solution. Characterisation of the particles using spectrometry showed them to be monodisperse with a λmax of 519 nm (Fig. S1A). The particles were imaged using TEM and had a mean diameter of 15.6 nm (Fig. S1B). The concentration measured using NP tracking analysis was 1.37 × 108 particles/ml.

3.2 Gold nanoparticle functionalisation

In order to conjugate F1-antigen onto the NPs a linker consisting of MHDA was first bound to the NP. The MHDA was covalently attached via a gold-sulphur bond, and formed a self-assembled monolayer projecting a carboxyl group for linkage to the protein. Carboxylated NPs were purified from the bulk material, by centrifugation and washing, and then characterised by spectrophotometry, which revealed a shift in λ max from 519nm to 525 nm (Fig. S1A).

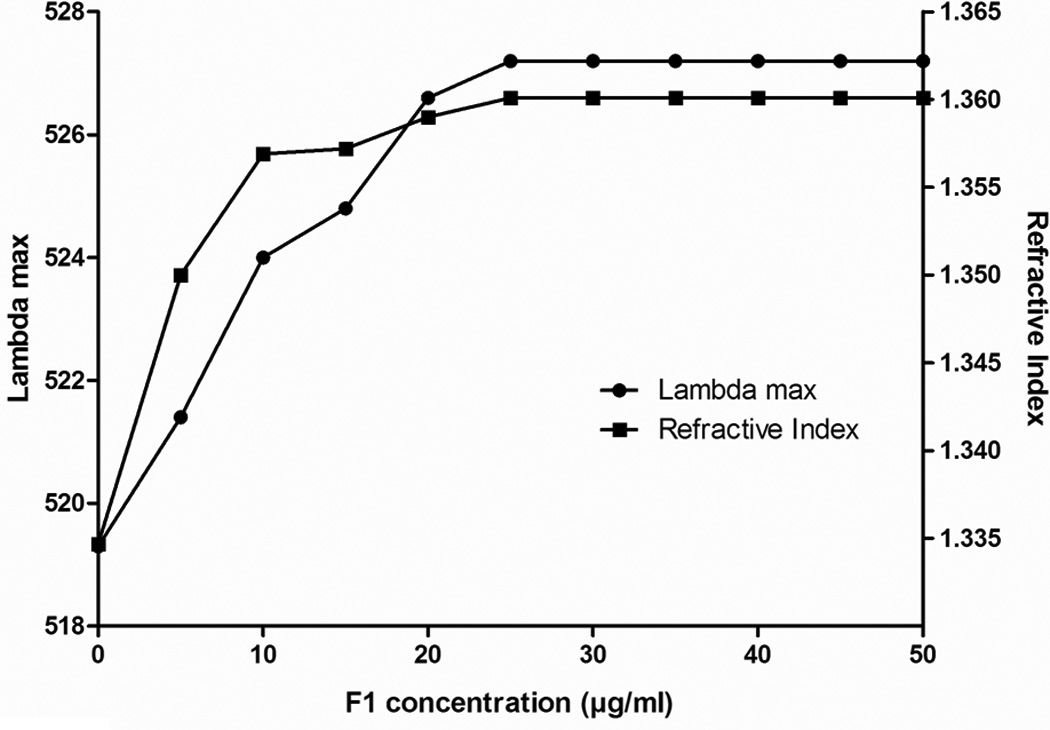

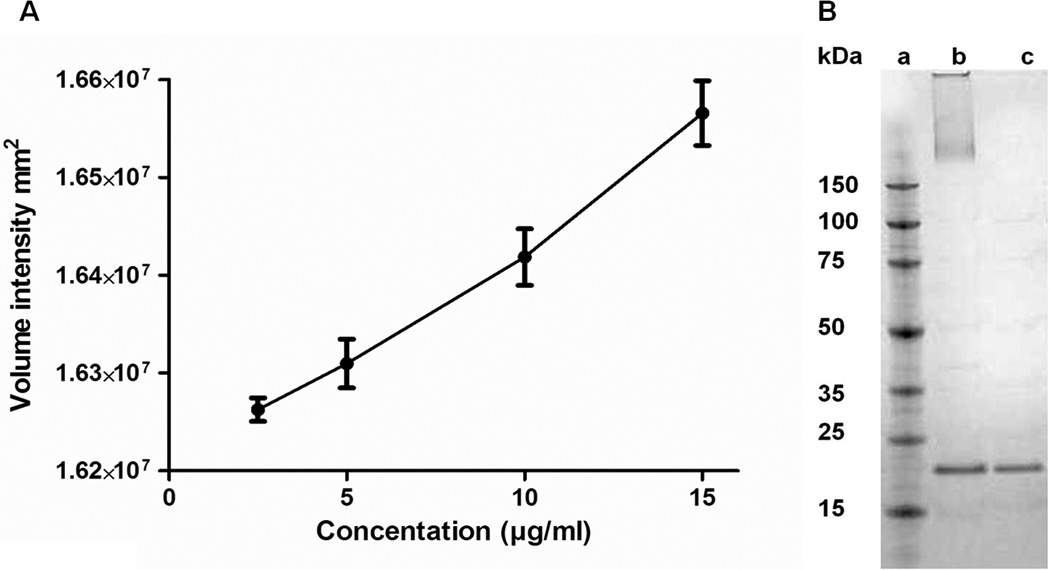

Carbodiimide coupling chemistry was used to conjugate the 15 kDa F1-antigen onto the MHDA linker. First, the concentration of F1-antigen required to saturate the NP surface was determined. Increasing concentrations of F1-antigen, in the range 0–50 µg/ml, were added to similar amounts of AuNPs. The binding of F1-antigen was assessed by monitoring the change in the wavelength of maximum absorption of visible light and also by the change in refractive index of the NPs [23]. This revealed that the NPs were saturated when 30 µg/ml of F1-antigen was added (Fig. 1). The amount of protein conjugated onto the NPs was measured by purifying the nano-conjugates, using centrifugation and washing, and re-suspending into 2-mercaptoethanol which released the F1-antigen. The released protein was analysed in a 4–12% Bis-Tris gel stained with Coomassie blue, where the relative intensity of the protein band could be quantified against a standard curve of known concentrations (Fig. 2). The amount of protein detected using this method was 0.3 µg of protein released from 10 µl NPs, equating to approximately 160 molecules per NP.

Fig. 1.

Minimum protein concentrations required for AuNP saturation was determined by measuring the shift in λmax with increasing F1-antigen concentration. Graph shows a representative data set from three replicates.

Fig. 2.

Quantification of gold nanoparticle conjugated protein (A) Relationship between density of protein band from gel and concentration. A standard curve was used to calculate protein concentration released from nanoconjugate (B) Coomassie blue stained gel showing protein displacement from gold nanoparticles a: Marker, b: AuNP-F1 treated with 11-mercapto 1-undecanol (AuNP at top of lane), c: 0.2 µg F1.

3.2 Immunisation study

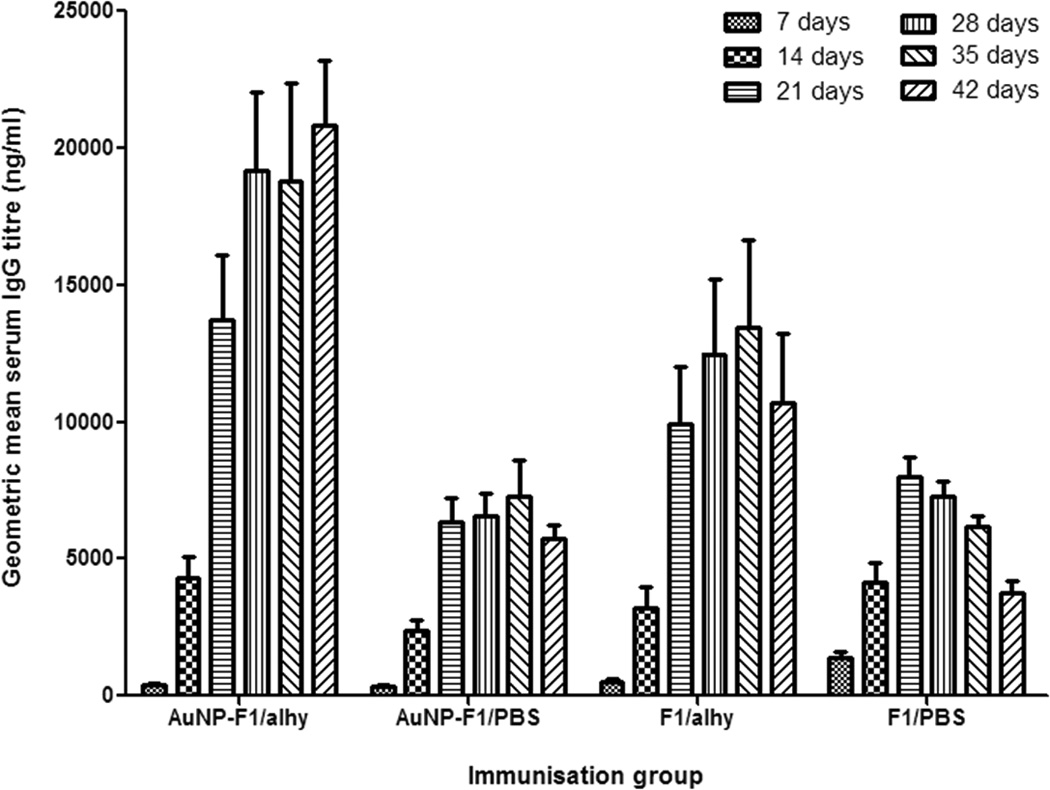

To evaluate the immunogenicity of the F1-antigen AuNP conjugated vaccine, BALB/c mice were immunised i.m. with a single dose of AuNP-F1 with or without an aluminium hydroxide adjuvant (alhydrogel). The animals were observed for six weeks and the development of antibody to F1-antigen in sera was measured using an ELISA (Fig. 3). Control mice received F1-antigen in either alhydrogel or PBS, or AuNPs alone. After 14 days, mice given AuNP-F1/alhy generated the greatest F1-antigen-specific antibody response when compared with AuNP-F1/PBS (p < 0.01). Mice immunised with F1/alhy generated a greater immune response than those in the groups with PBS instead of alhydrogel (p < 0.01). There was a significant decline in IgG titres from mice immunised with unconjugated F1-antigen with or without alhydrogel from days 35 or 21 days respectively, post immunisation (p < 0.01). Mice given AuNP-F1/alhy showed no decline in IgG titre at 42 days post-immunisation. Mice immunised with empty AuNPs alone did not develop antibody against F1-antigen (data not shown). In all of the immunised groups the concentration of F1-specific IgG1 exceeded IgG2a (Table 1). However, the concentration of F1-specific IgG2a in mice immunised with AuNP-F1/PBS was significantly increased compared with mice administered unconjugated F1/PBS (p < 0.05). Formulation of AuNP-F1/alhy significantly increased both IgG1 and IgG2a responses, (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively), compared with AuNP-F1/PBS.

Fig. 3.

Relative concentrations of F1-specific total IgG in sera from BALB/c mice at different times after giving a single dose of the immunogens indicated. After 14 days, mice immunised with gold AuNP-F1/alhy generated a significantly higher IgG titre compared with AuNP-F1/PBS or unconjugated F1-antigen in PBS (P < 0.01). AuNP-F1/alhy immunised mice did not show a decline in IgG at 42 days post-immunisation. Each point is the mean of values from five mice.

Table 1.

Analysis of F1-specific IgG1 and IgG2a isotypes in sera taken from immunised mice. The concentration of F1-specific IgG2a in mice immunised with AuNP-F1/PBS was significantly increased compared with mice administered unconjugated F1/PBS (p<0.05). Formulation of AuNP-F1/alhy significantly increased both IgG1 and IgG2a responses, (p<0.01 and p<0.05, respectively), compared with AuNP-F1/ PBS

| Vaccine Group | IgG1 (µg/ml) | IgG2a (µg/ml) | Ratio IgG1:IgG2a |

|---|---|---|---|

| AuNP-F1/alhy | 22.95 ± 3.83 | 1.67 ± 0.11 | 13.75 |

| AuNP-F1/PBS | 6.59 ± 0.86 | 0.98 ± 0.13 | 6.72 |

| F1/alhy | 12.53 ± 3.15 | 0.86 ± 0.18 | 14.57 |

| F1/PBS | 6.46 ± 0.39 | 0.46 ± 0.07 | 14.04 |

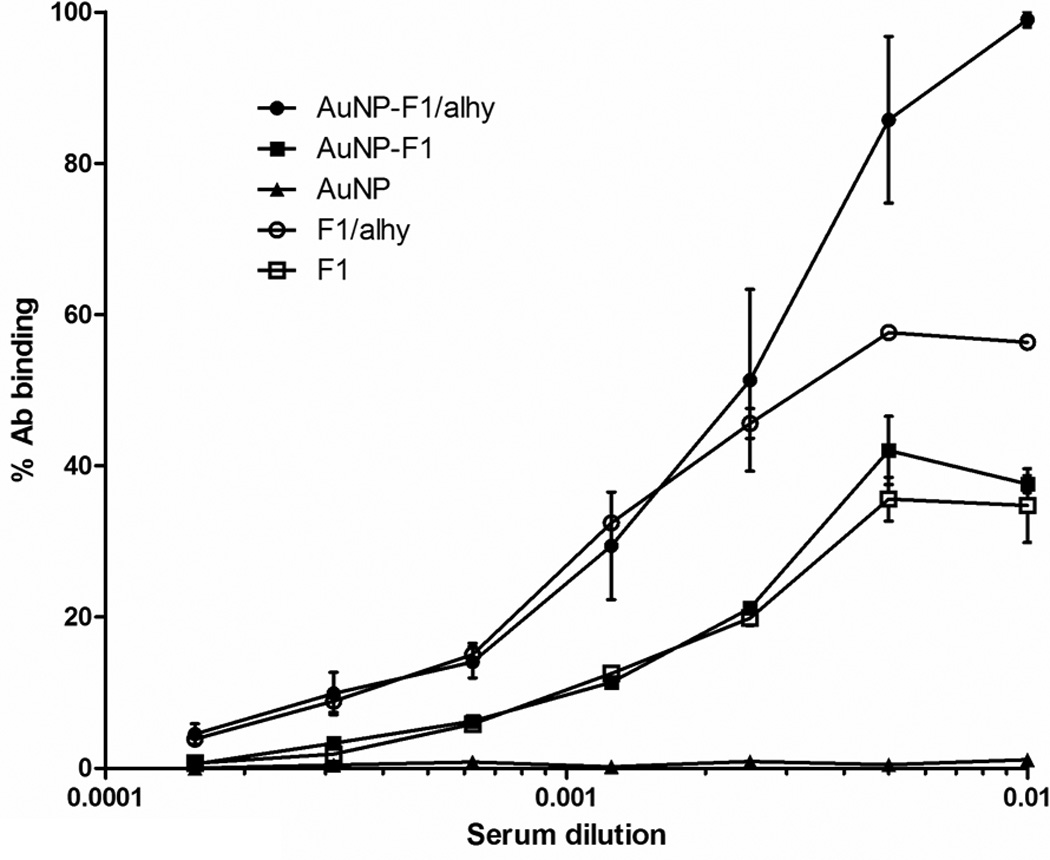

Sera collected from mice in individual treatment groups were assesed for their abilities to compete with sera from macaques previously immunised with F1-antigen. This sera has been shown to passively protect mice from a Y. pestis challenge [24]. The sera from mice immunised with F1-antigen formulations was able to displace the macaque sera (Fig. 4). Sera from animals immunised with AuNP-F1/alhy competed most succesfully with the macaque antibody, with a significantly greater percentage bind than any other group for the intial two dilutions (p < 0.01). Sera from mice immunised with AuNP-F1 or unconjugated F1-antigen competed similarly with the macaque sera.

Fig. 4.

Competitive ELISA for binding to F1-antigen. After 14 days, mice immunised with AuNP-F1/alhy generated a significantly higher IgG titre compared with AuNP-F1/PBS and unconjugated F1-antigen in PBS (P < 0.01). Mice dosed with AuNP-F1/alhy did not show a decline in total IgG at 42 days post-immunisation. Each point is the mean of values from five mice.

3.3 Flow cytometric analysis

Flow cytometric analysis showed that a high percentage of cells positive for the activation/maturation marker CD45 existed in all treatment groups (Table 2). CD4+ cells as a percentage of cells bearing the pan T-cell marker (CD3) exceeded CD8+ cells as a percentage of the CD3+ population, for all treatment groups, with no significant differences between groups. Analysis of IFNγ in culture supernatants of splenocytes re-stimulated ex vivo with F1-antigen, revealed a significantly reduced level from cells obtained from mice immunised with AuNP-F1/alhy, compared with those from mice administered F1/PBS (P < 0.05), indicating the anti-inflammatory influence of alhydrogel in the vaccine formulation.

Table 2.

Percentage of CD3+ splenocytes displaying the activation marker CD45 on ex vivo re-stimulation with F1-antigen. For all treatment groups, CD3+CD4+ cells outnumbered CD3+CD8+ cells by approximately 2:1, with no significant differences between groups. The secretion of IFNγ by restimulated splenocytes was significantly reduced in the group receiving AuNP-F1/alhydrogel, compared with the F1/PBS group (p<0.05).

| Vaccine group | CD45+ (% of CD3+ cells ± s.e.m.) specifically activated by F1 ex vivo |

IFNγ output (ng/ml ± s.e.m.) in recall response specific for F1 |

|---|---|---|

| AuNP-F1/alhy | 89.8 ± 2.2 | 327 ± 24 |

| AuNP-F1/PBS | 86.0 ± 5.0 | 704 ± 187 |

| F1/alhy | 82.04 ± 10.3 | 542 ± 121 |

| F1/PBS | 74.8 ± 14 | 775 ± 113 |

4. Discussion

Previous studies have shown that i.m. immunisation with recombinant F1-antigen induces a protective immune response against Y. pestis [3, 5, 22]. There is also potential for a subunit vaccine composed of Y. pestis F1-antigen and recombinant V antigen (a secreted Y. pestis protein) encapsulated within polylactide microspheres to replace the current killed whole cell vaccine [22, 25]. Although promising, the immmmune response to this vaccine was reported to be slow to develop, atrributed to the slow release of antigen from the microparticles; something which is true of many encapsulation strategies [26–28]. It would therefore be favourable to develop a delivery system which is not only self-adjuvanting but induces an appropriate immune response for protection without the need for multiple dosing.

Much attention has now turned to NPs as a method for delivering vaccines [29–36]. In this study we have used F1-antigen coupled to 15 nm AuNPs. By ensuring that a non-ionic detergent, such as Triton X-100, was present during the conjugation process, we were able to separate NP-bound from free F1-antigen by centrifugation, avoiding inefficient gel chromatography steps. This method may be useful to other workers aiming to generate gold nanoconjugate vaccines.

When immunised i.m. into mice, F1 conjugated to AuNP induced antibody responses which were superior to the responses induced by F1-antigen alone. NP conjugated F1 also generated higher IgG2a titres suggesting activation of Th1 cells. However, IFNγ levels from splenocytes taken from mice immunised with AuNP-F1/alhy were lower than from mice immunised with F1/PBS or with AuNP-F1/PBS. This indicates that the incorporation of alhydrogel into the formulation supressed IFNγ responses. Unlike other studies using microspheres to deliver antigens, our data shows no delay in the induction of antibody. This is likely to be attributed to the presentation of F1-antigen on the NP surface. Similarly an attenuated strain of Salmonella Typhimurium expressing F1-antigen on its surface was a potent immunogen and protected mice against challenge with Y. pestis (24).

Other workers [37–39] have reported the ability of AuNPs to enhance the ability of antigen to evoke antibody responses compared with antigen given alone. In the case of merozoite surface protein 1 or Nogo-66 receptor, coupling to AuNPs resulted in antibody responses exceeding those elicited by the antigen given with Freunds adjuvant [38, 39]. Some workers have reported that the use of alum as an adjuvant further enhanced the responses elicited by antigen bound to AuNPs [38] but others have used antigen bound to AuNPs without an additional adjuvant [37, 39]. We found that the use of alum as an adjuvant enhanced the antibody response to F1-antigen linked to AuNPs.

F1 is a proven antigen which we know from the published literature to be immunogenic and protective against Y. pestis [40, 41]. Whilst we have not challenged immunised mice in this study the ability of sera from mice immunised with AuNP-F1 to compete with a protective macaque antiserum [40–42] for binding to F1-antigen indicates that the AuNP-F1 has induced a protective antbody response. Thus we conclude that the conjugation of F1-antigen to AuNPs has been succesfully achieved without interference with protective B-cell epitopes in F1-antigen.

Whilst our results are encouraging, the utility of NPs as vaccine carriers requires further investigation. Gold has been used widely in medicine, but some recent publications suggest that AuNPs can accumulate within tissues and elicit toxic effects [43, 44]. These reports involve studies where high doses of NPs are repeatedly given intraperitoneally. In contrast there is also literature indicating no evidence of toxicity associated with AuNPs [39, 45] and it is possible that single doses of NPs given intramuscularly are not toxic. The toxicity of gold might also be influenced by its phsyical state. In the case of TiO2 and Cu2O, nanoparticles have been shown to be toxic inducing tissue damage and production of reactive oxygen species [44, 46–48], although larger particles lack toxicity. Further work is also required to determine the fate of AuNPs given intramuscularly and, the mechanisms by which AuNPs are taken up into antigen presenting cells requires clarification.

Supplementary Material

Characterisation of AuNPs. (A) Optical extinction profile of gold nanoparticles using a UV-visible spectrophotometer. λmax for AuNP was 519nm (solid), λ max for carboxylated AuNP was 525nm (dashed) and λmax for F1-antigen conjugated to AuNP was 532nm (dotted). (B) Image of gold nanoparticles taken with a Jeol JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope measured an average diameter of 15.6 nm.

Highlights.

A novel method to deliver Y. pestis F1-antigen using Au nanoparticles is proposed.

Conjugation of F1-antigen to Au nanoparticles improves immunogenicity.

F1-antigen coupled Au nanoparticles enhanced the IgG2a immune response in mice.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by grant number U54 AI057156 from the Western Regional Center for Excellence, USA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Evans RG, Crutcher JM, Shadel B, Clements B, Bronze MS. Terrorism from a public health perspective. Am J Med Sci. 2002 Jun;323(6):291–298. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perry RD, Fetherston JD. Yersinia pestis—Etiologic Agent of Plague. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1997;10:35–66. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simpson WJ, Thomas RE, Schwan TG. Recombinant capsular antigen (fraction 1) from Yersinia pestis induces a protective antibody response in BALB/c mice. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990 Oct;43(4):389–396. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.43.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williamson ED, Eley SM, Griffin KF, Green M, Russell P, Leary SE, et al. A new improved sub-unit vaccine for plague: the basis of protection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1995 Dec;12(3–4):223–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews GP, Heath DG, Anderson GW, Jr, Welkos SL, Friedlander AM. Fraction 1 capsular antigen (F1) purification from Yersinia pestis CO92 and from an Escherichia coli recombinant strain and efficacy against lethal plague challenge. Infect Immun. 1996 Jun;64(6):2180–2187. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2180-2187.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson ED, Flick-Smith HC, LeButt C, Rowland CA, Jones SM, Waters EL, et al. Human Immune Response to a Plague Vaccine Comprising Recombinant F1 and V Antigens. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3598–3608. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3598-3608.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fellows P, Adamovicz J, Hartings J, Sherwood R, Mega W, Brasel T, et al. Protection in mice passively immunized with serum from cynomolgus macaques and humans vaccinated with recombinant plague vaccine (rF1V) Vaccine. 2010;28(49):7748–7756. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hart MK, Saviolakis GA, Welkos SL, House RV. Advanced Development of the rF1V and rBV A/B Vaccines: Progress and Challenges. Advances in Preventive Medicine. 2012;2012:14. doi: 10.1155/2012/731604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fahmy TM, Fong PM, Park J, Constable T, Saltzman WM. Nanosystems for simultaneous imaging and drug delivery to T cells. Aaps J. 2007;9(2):E171–E180. doi: 10.1208/aapsj0902019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bawarski WE, Chidlowsky E, Bharali DJ, Mousa SA. Emerging nanopharmaceuticals. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology, and Medicine. 2008;4:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen S, Kimura K. Synthesis and Characterization of Carboxylate-Modified Gold Nanoparticle Powders Dispersible in Water. Langmuir. 1999;15:1075–1082. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen YS, Chen SC, Kao CM, Chen YL. Effects of soil pH, temperature and water content on the growth of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2003;48(2):253–256. doi: 10.1007/BF02930965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turkevich J, Stevenson PC, Hillier J. A study of the nucleation and growth processes in the synthesis of colloidal gold. Discuss Faraday Soc. 1951;11:55–75. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chithrani BD, Ghazani AA, Chan WCW. Determining the Size and Shape Dependence of Gold Nanoparticle Uptake into Mammalian Cells. Nano Letters. 2006;6(4):662–668. doi: 10.1021/nl052396o. 03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor U, Klein S, Petersen S, Kues W, Barcikowski S, Rath D. Nonendosomal cellular uptake of ligand-free, positively charged gold nanoparticles. Cytometry Part A : the journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology. 2010 May;77(5):439–446. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia T, Rome L, Nel A. Nanobiology: Particles slip cell security. Nat Mater. 2008;7(7):519–520. doi: 10.1038/nmat2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhumkar D, Joshi H, Sastry M, Pokharkar V. Chitosan Reduced Gold Nanoparticles as Novel Carriers for Transmucosal Delivery of Insulin. Pharmaceutical Research. 2007;24(8):1415–1426. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9257-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan Y, Li Y-j, Zhao H-y, Zheng J-m, Xu H, Wei G, et al. Bioadhesive polysaccharide in protein delivery system: chitosan nanoparticles improve the intestinal absorption of insulin in vivo. Int J Pharm. 2002;249(1–2):139–147. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuller DH, Loudon P, Schmaljohn C. Preclinical and clinical progress of particle-mediated DNA vaccines for infectious diseases. Methods. 2006;40(1):86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo D, Saltzman WM. Synthetic DNA delivery systems. Nat Biotech. 2000;18(1):33–37. doi: 10.1038/71889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller J, Williamson ED, Lakey JH, Pearce MJ, Jones SM, Titball RW. Macromolecular organisation of recombinant Yersinia pestis F1 antigen and the effect of structure on immunogenicity. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1998 Jul;21(3):213–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williamson DE, Sharp GJE, Eley SM, Vesey PM, Pepper TC, Titball RW, et al. Local and systemic immune response a microencapsulated sub-unit vaccine to for plague. Vaccine. 1996;14:1613–1619. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brewer SH, Glomm WR, Johnson MC, Knag MK, Franzen S. Probing BSA Binding to Citrate-Coated Gold Nanoparticles and Surfaces. Langmuir. 2005;21:9303–9307. doi: 10.1021/la050588t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williamson ED, Packer PJ, Waters EL, Simpson AJ, Dyer D, Hartings J, et al. Recombinant (F1+V) vaccine protects cynomolgus macaques against pneumonic plague. Vaccine. 2011;29(29–30):4771–4777. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quenee LE, Ciletti NA, Elli D, Hermanas TM, Schneewind O. Prevention of pneumonic plague in mice, rats, guinea pigs and non-human primates with clinical grade rV10, rV10-2 or F1-V vaccines. Vaccine. 2011;29(38):6572–6583. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alonso MJ, Gupta RK, Min C, Siber GR, Langer R. Biodegradable microspheres as controlled-release tetanus toxoid delivery systems. Vaccine. 1994;12(4):299–306. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alonso MJ, Cohen S, Park TG, Gupta RK, Siber GR, Langer R. Determinants of Release Rate of Tetanus Vaccine from Polyester Microspheres. Pharmaceutical Research. 1993;10(7) doi: 10.1023/a:1018942118148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Hagan DT, Jeffery H, Roberts MJJ, McGee JP, Davis SS. Controlled release microparticles for vaccine development. Vaccine. 1991;9(10):768–771. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90295-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demento SL, Cui W, Criscione JM, Stern E, Tulipan J, Kaech SM, et al. Role of sustained antigen release from nanoparticle vaccines in shaping the T cell memory phenotype. Biomaterials. 2012 Jun;33(19):4957–4964. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musumeci T, Ventura CA, Giannone I, Ruozi B, Montenegro L, Pignatello R, et al. PLA/PLGA nanoparticles for sustained release of docetaxel. Int J Pharm. 2006;325(1–2):172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahapatro A, Singh DK. Biodegradable nanoparticles are excellent vehicle for site directed in-vivo delivery of drugs and vaccines. Journal of nanobiotechnology. 2011;9:55. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-9-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emeny RT, Wheeler CM, Jansen KU, Hunt WC, Fu TM, Smith JF, et al. Priming of human papillomavirus type 11-specific humoral and cellular immune responses in college-aged women with a virus-like particle vaccine. J Virol. 2002 Aug;76(15):7832–7842. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.15.7832-7842.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giannini SL, Hanon E, Moris P, Van Mechelen M, Morel S, Dessy F, et al. Enhanced humoral and memory B cellular immunity using HPV16/18 L1 VLP vaccine formulated with the MPL/aluminium salt combination (AS04) compared to aluminium salt only. Vaccine. 2006;24(33–34):5937–5949. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uto T, Akagi T, Hamasaki T, Akashi M, Baba M. Modulation of innate and adaptive immunity by biodegradable nanoparticles. Immunol Lett. 2009 Jun 30;125(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uto T, Wang X, Sato K, Haraguchi M, Akagi T, Akashi M, et al. Targeting of antigen to dendritic cells with poly(gamma-glutamic acid) nanoparticles induces antigen-specific humoral and cellular immunity. J Immunol. 2007 Mar 1;178(5):2979–2986. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caputoa A, Castaldello A, Brocca-Cofanoa E, Voltana R, Bortolazzi F, Altavilla G, et al. Induction of humoral and enhanced cellular immune responses by novel core–shell nanosphere- and microsphere-based vaccine formulations following systemic and mucosal administration. Vaccine. 2009;27:3605–3615. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen YS, Hung YC, Lin WH, Huang GS. Assessment of gold nanoparticles as a size-dependent vaccine carrier for enhancing the antibody response against synthetic foot-and-mouth disease virus peptide. Nanotechnology. 2010 May 14;21(19):195101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/19/195101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parween S, Gupta PK, Chauhan VS. Induction of humoral immune response against PfMSP-1(19) and PvMSP-1(19) using gold nanoparticles along with alum. Vaccine. 2011 Mar;29(13):2451–2460. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y-T, Lu X-M, Zhu F, Huang P, Yu Y, Zeng L, et al. The use of a gold nanoparticle-based adjuvant to improve the therapeutic efficacy of hNgR-Fc protein immunization in spinal cord-injured rats. Biomaterials. 2011;32(31):7988–7998. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williamson ED, Eley SM, Stagg AJ, Green M, Russell P, Titball RW. A sub-unit vaccine elicits IgG in serum, spleen cell cultures and bronchial washings and protects immunized animals against pneumonic plague. Vaccine. 1997 Jul;15(10):1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williamson ED, Vesey PM, Gillhespy KJ, Eley SM, Green M, Titball RW. An IgG1 titre to the F1 and V antigens correlates with protection against plague in the mouse model. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999 Apr;116(1):107–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williamson ED, Flick-Smith HC, Waters E, Miller J, Hodgson I, Le Butt CS, et al. Immunogenicity of the rF1+rV vaccine for plague with identification of potential immune correlates. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2007;42(1):11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abdelhalim MAK, Mady MM. Liver uptake of gold nanoparticles after intraperitoneal administration in vivo: A fluorescence study. Lipids Health Dis. 2011 Oct;10:9. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-10-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamamoto A, Honma R, Sumita M, Hanawa T. Cytotoxicity evaluation of ceramic particles of different sizes and shapes. Journal of biomedical meaterials research part A. 2003;68A(2):244–256. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Connor EE, Mwamuka J, Gole A, Murphy CJ, Wyatt MD. Gold nanoparticles are taken up by human cells but do not cause acute cytotoxicity. Small. 2005;1:325–327. doi: 10.1002/smll.200400093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lasagna-Reeves C, Gonzalez-Romero D, Barria MA, Olmedo I, Clos A, Sadagopa Ramanujam VM, et al. Bioaccumulation and toxicity of gold nanoparticles after repeated administration in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010 Mar 19;393(4):649–655. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lovric J, Cho SJ, Winnik FM, Maysinger D. Unmodified Cadmium Telluride Quantum Dots Induce Reactive Oxygen Species Formation Leading to Multiple Organelle Damage and Cell Death. Chemistry & Biology. 2005;12(11):1227–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen D, Zhang D, Yu JC, Chan KM. Effects of Cu2O nanoparticle and CuCl2 on zebrafish larvae and a liver cell-line. Aquat Toxicol. 2011 Oct;105(3–4):344–354. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Characterisation of AuNPs. (A) Optical extinction profile of gold nanoparticles using a UV-visible spectrophotometer. λmax for AuNP was 519nm (solid), λ max for carboxylated AuNP was 525nm (dashed) and λmax for F1-antigen conjugated to AuNP was 532nm (dotted). (B) Image of gold nanoparticles taken with a Jeol JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope measured an average diameter of 15.6 nm.