Abstract

Background and purpose

In skeletally immature patients, surgical options due to recurrent patella dislocation are limited, because bony procedures bear the risk of growth disturbances. In this retrospective study, we report the long-term functional and radiographic outcome in skeletally immature patients using the modified Grammont surgical technique.

Patients

Between 1999 and 2004, 65 skeletally immature knees (49 children) were treated with a modified Grammont procedure: an open lateral release and a shift of the patella tendon insertion below the growth plate on the tuberositas tibia, allowing the tendon to medialize. At mean 8 (5.6–11) years after surgery, 58 knees in 43 patients were evaluated by clinical examination, from functional scores (Lysholm, Tegner), and from radiographs of the knees.

Results

Mean Lysholm score was 82 postoperatively. Tegner score decreased from 6.2 to 5. Eight knees had a single dislocation within 3 months of surgery. 3 knees had repeated late dislocations, all with a high grade of trochlea dysplasia. 6 knees showed mild signs of osteoarthritis. No growth disturbances were observed.

Interpretation

The modified Grammont technique in skeletally immature patients allows restoration of the distal patella tendon alignment by dynamic positioning. Long-term results showed that there were no growth disturbances and that there was good functional outcome. However, patients with a high grade of trochlea dysplasia tended to re-dislocate.

The incidence of patella dislocation in children and adolescents is between 29 and 77 per 105 individuals per year, and it is higher in girls (Nietosvaara et al. 1994). About 80% of patella dislocations and recurrent instability can be attributed to predisposing factors such as bone dysplasias (e.g. trochlea dysplasia, patella alta, or dysplastic patella) (Dejour et al. 1994), axial deformities, and rotational deformities of the lower limb (increased Q-angle). Positive correlations have been found between hyperlaxity of the ligaments and positive family history on the one hand and an increased incidence of patella dislocation on the other (Buchner et al. 2005, Palmu et al. 2008).

Nonoperative management is recommended for first-time patella dislocations in the skeletally immature (Nikku et al. 2005, Sillanpaa et al. 2009), with early motion and quadriceps strengthening after initial long leg casting or bracing (Palmu et al. 2008). Re-dislocations may, however, occur in two-thirds of these patients (Arendt et al. 2002, Palmu et al. 2008) and operative treatment to re-align the patella may be necessary. Due to the open physe and residual growth, operative bony procedures are limited. Also, only a few reports have included long-term outcome (Nikku et al. 2005, Sillanpaa et al. 2009).

Grammont et al. (1985) described a technique for patella re-alignment with a lateral release and medial fixation of the patella tendon on the tibial tubercle (Grammont et al. 1985). Here we report a surgical technique involving a modified Grammont procedure with “dynamic placement” of the tibial tubercle for the correct positioning and alignment of the tibial tubercule. We also report the long-term functional and radiographic outcome in skeletally immature patients.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the pediatric database at our institution at the Department of Paediatric and Adolescent Surgery at the Medical University of Graz to identify children and adolescents who underwent surgery for patella dislocation between 1999 and 2004. The inclusion criteria were (1) recurrent patella dislocation or first-time patella dislocation with an osteochondral fragment as identified on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), (2) open physis at the time of surgery, (3) surgery using the modified Grammont technique, (4) preoperative anteroposterior (AP) and lateral-view radiographs of the knee joint, (5) compliance with the postoperative rehabilitation protocol, and (6) a follow-up of at least 6 years.

Exclusion criteria were (1) patients with associated syndromes (e.g. Marfan, Ehler-Danlos), (2) incomplete preoperative radiographs, (3) previous surgery on the affected knee, or (4) deviation from the standard rehabilitation protocol.

49 patients (65 knees) were identified, with 43 patients (58 knees) completing final follow-up at 8.4 (5.5–11) years. 4 patients (5 knees) were lost to follow-up due to lost postal address, and 2 patients did not want to come back (2 knees). There were 10 males and 33 females with a mean age at operation of 14.6 (12.7–16) years for males and 13.4 (11.3–15.3) years for females. There were 15 bilateral cases, 16 left-sided and 12 right-sided. 33 patients (46 knees) had isolated patella re-alignment and 10 patients (12 knees) also had concomitant operative fixation of an associated osteochondral fragment.

Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committee (no. 20-465 ex 08/09). Patients who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were invited for follow-up.

Clinical outcome

Axial deviations of the knee in the frontal (varus/valgus) and sagittal plane (recurvatum) and for measuring femoral and tibial torsion (Barbee Ellison et al. 1990) were measured clinically using a goniometer. Range of movement of the hip and knee and ligament stability of the knee were also investigated. Activity was rated using the Tegner score (Tegner and Lysholm 1985) and postoperative function was rated using the Lysholm score (Lysholm and Gillquist 1982). The visual analog scale (VAS) was used to evaluate pain during activities of daily living.

Radiographic assessment

Standard AP, lateral-, and Merchant-view radiographs of the operated knee were taken. The Blackburne-Peel index (Blackburne and Peel 1977) was measured to assess patella height. Osteoarthritic changes were graded according to Kellgren and Lawrence (Kellgren and Lawrence 1957). Trochlear dysplasia was classified according to Dejour et al. (1994). Patellofemoral congruence was measured using the Merchant angle (Merchant et al. 1974) and the sulcus angle of Brattström (1964).

Operative technique

Under general anesthesia with the patient positioned supine, a high thigh tourniquet was applied. Arthroscopy was performed on all patients to rule out any other intra-articular pathology, to assess osteochondral damage, and to remove loose bodies. Following arthroscopy, a lateral incision was made starting at the mid-patella level and extending distally to include the anterolateral arthroscopy portal, to reach 1 cm below the tibial tuberosity (Figures 1A and 2A). Figure 3A shows a sagittal-plane view of the proximal tibia indicating the relationship between the patellar tendon insertion and the anterior tongue of the physis. In the 12 knees with concomitant osteochondral fragments identified at arthroscopy (10 patients), the incision was extended proximally (Figure 2B), allowing access to the lateral femoral condyle—or to turn around the patella for inspection of the medial patella facet. The medial patella facet and the lateral femoral condyle are the areas with most frequent chondral damage due to patella dislocations.

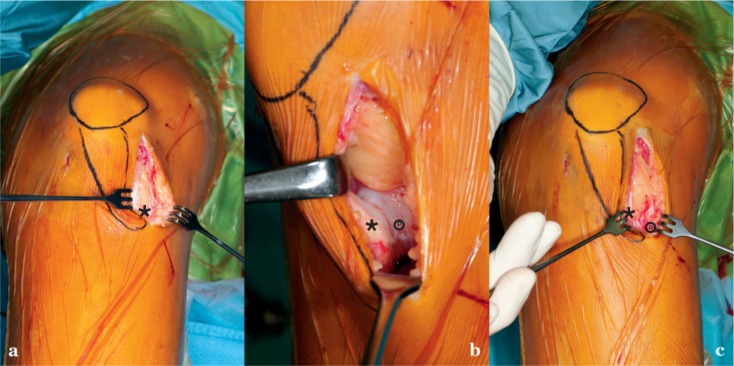

Figure 1.

a. Lateralized left patella tendon shown through incision. * lateral fixed patellar ligament.

b. The patella tendon dissected sharply from the tibial tuberosity. Then the periosteum gets detached from the tibial crest by using a rasp (° tibial tuberosity, * patellar ligament).

c. New medialized position of the patella tendon through the incision (° tibial tuberosity, * detached patellar ligament).

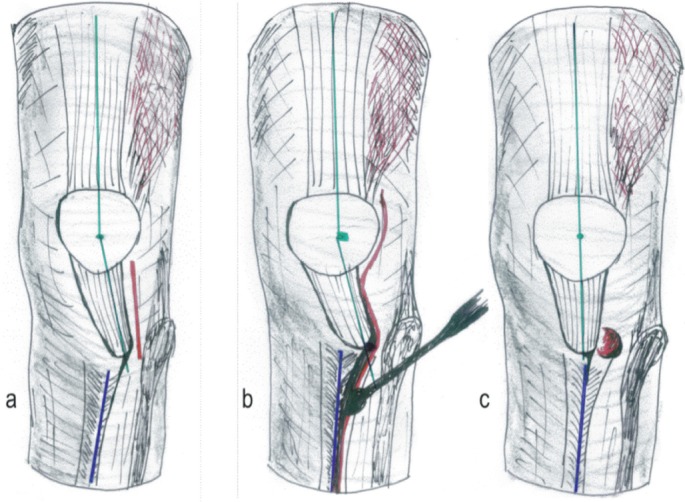

Figure 2.

Schematic drawing of left knee. a. Following arthroscopy, a lateral incision was made starting at the mid-patellar level and extending distally to include the anterolateral arthroscopy portal to reach 1 cm below the tibial tuberosity. b. and c. In cases with concomitant osteochondral fragments, the incision was extended proximally allowing access to the lateral femoral condyle or the patella facet (red). Starting at the tibial tuberosity, the periosteum was split along the tibial crest for 6–8 cm distally without opening the fascia of the tibialis anterior muscle (red). The periosteum was subsequently detached from the tibial crest with a large rasp (blue). In knee flexion, the patella tendon then slides spontaneously medially to track within the femoral groove. Patella alignment was restored (green).

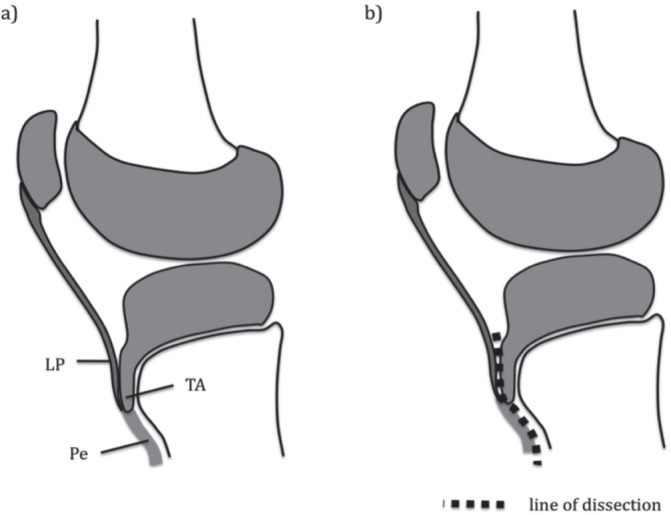

Figure 3.

a. Sagittal-plane view of the proximal tibia (deep incision) indicating the relation of the patellar tendon insertion and the anterior tongue of the physis. Note that the physis remains untouched. LP: ligamentum patellae; TA: anterior tongue of the physis; Pe; periosteum. b. The patella tendon gets sharply dissected from the tibial tuberosity. The periosteum is then split along the tibial crest and detached distally by rasp. This leads to a spontaneous slide of the patella tendon medially.

The osteochondral fragments were fixed using Arthrex chondral darts (Arthrex Inc., Naples, FL) or a small fragment screw, which was countersunk. With cutting of the lateral retinaculum near the patella, about 1 cm up to the fibers of the lateral vastus muscle, a lateral release was performed. The superficial oblique fibers were dissected from the deep transverse fibers. Subsequently, the deep transverse retinaculum was then divided from the underlying capsule. In the layer between the lateral retinaculum and the joint capsule, the subcutaneous tissue was mobilized proximally to distally. The deep fascia was split to reach the lateral part of the patella tendon, to expose the insertion of the patella ligament at the tibial tuberosity.

Finger mobilization of the subcutaneous tissue was performed along the tibial crest and from the patella ligament. The cartilage of the tibial tuberosity was then separated from the patella tendon by sharp dissection (Figure 1B and 3B). Once the insertion of the patella tendon had been separated from the tibial tuberosity, the tendon only remained attached to the distal periosteum. Starting at the tibial tuberosity, the periosteum was split along the tibial crest distally to the middle of the tibial shaft without opening the fascia of the tibialis anterior muscle. The periosteum was then detached from the tibial crest with a large rasp (Figure 2B). In knee flexion, the patella tendon was then allowed to spontaneously slide medially to track within the femoral groove. In contrast to the original technique described by Grammont et al. (1985), no medial fixation of the patella tendon onto the tibia was performed. Instead, the tendon was allowed to reside in its self-selected position (Figures 1C and 2C). The Hoffa fat pad and the “former” tuberosity were now covered on the medial side of the tendon only. The tourniquet was released and hemostasis was performed. A subcutaneous drain was inserted and the subcutaneous tissue and the dermis were closed.

Postoperative treatment and rehabilitation

Immediately after surgery, continuous passive motion (CPM) within a range of 30–60° of knee flexion was started for 3 days to facilitate positioning of the “new” tuberosity. The drain was removed on the second postoperative day and isometric muscle activation started. Physiotherapy was commenced 2 days after surgery to regain muscle strength and full range of movement of the knee. Subsequently, the patients were mobilized on forearm crutches, bearing half of their body weight on the operated limb for 4 weeks, after which full weight bearing was started.

In cases where osteochondral fragments were fixed, patients remained non-weight bearing on the operated limb for 6 weeks, and in addition an orthosis was used to restrict knee flexion to 60°. After this period, the orthosis was discarded and full weight bearing was allowed, with no restriction in range of movement of the knee. Return to sporting activity was allowed 3 months after surgery.

Statistics

The statistical significance between pre- and postoperative visual analog score, sulcus angle, Blackburne-Peel index, and the Merchant angle were determined using paired t-test. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. In addition, for comparison of preoperative and postoperative Merchant views, results are given as mean with range and 95% confidence interval (CI). We used SPSS software version 16.0 for Macintosh.

Results

Clinical examination

At final follow-up, all the patients showed a symmetrical frontal and sagittal plane axis of the lower limbs. 50 hips showed increased internal rotation (> 50°) and 16 tibia showed increased external torsion (> 25°). 4 patients (3 males) had slight varus (< 10°) and 10 patients (9 males) had slight valgus (< 10°) of the knee. There was no genu recurvatum. Symmetrical range of knee movement and joint stability of the knee was found in each patient irrespective of whether there was unilateral or bilateral surgery (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and range of knee movement

| Patella re-alignment | Patella re-alignment and osteochondral fragment fixation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Age (chronological) | 14.6 | 13.2 | 14.9 | 13.6 |

| No. of patients | 8 | 25 | 2 | 8 |

| No. of knees | 11 | 35 | 2 | 10 |

| Bilateral cases | 3 | 10 | 0 | 2 |

| Left knee | 2 | 7 | 2 | 5 |

| Right knee | 3 | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| Knee ROM | 3.5/0/135 | 2.6/0/142.2 | 5/0/140 | 0/0/141 |

| range from | 0/0/130 | 0/0/130 | 0/0/130 | 0/0/130 |

| to | 10/0/145 | 15/0/145 | 10/0/145 | 0/0/145 |

Clinical outcome

The level of activity decreased by one level, from a Tegner score of 6.2 (2–10) to 5 (2–9) (p < 0.001). The Lysholm score postoperatively was 82 (52–100). Following surgery, the level of pain during activities of daily living—as assessed by the visual analog score—improved from a mean of 6.2 (0–10) to a mean of 2.6 (0–8) (p < 0.001).

Radiographic assessment

At follow-up, 6 of 58 of knees showed first- to second-degree signs of osteoarthritis according to the classification of Kellgren and Lawrence (Kellgren and Lawrence 1957). Of these, 3 knees also had concomitant fixation of an osteochondral fragment at the time of surgery.

Preoperative lateral radiographs were evaluated for signs of trochlear dysplasia and were classified according to Dejour et al. (1994). 10 knees showed no signs of patellofemoral dysplasia (Table 2).

Table 2.

Preoperative evaluation of trochlear dysplasia

| Dejour grades of trochlear dysplasia |

Radiographic sign | No. of knees |

|---|---|---|

| Grade A | Crossing sign | 30 |

| Grade B | Crossing sign Supratrochlear spur |

14 |

| Grade C | Crossing sign Double contour |

4 |

| Grade D | Crossing sign Supratrochlear spur Double contour |

0 |

Patellofemoral incongruence was evaluated by calculating the Merchant angle (normal angle: < 16°). For comparison of preoperative and postoperative values, 46 radiographs were available. Preoperatively, 41 of 46 of knees had a Merchant angle of greater than 16° (mean 31° (SD 12; range 5–56; CI: ± 3.4)). The mean postoperative Merchant angle was 16° (SD 10; range 0–44; CI: ± 2.9).

Patella height was similar preoperatively and postoperatively. The Blackburne-Peel index was 0.98 (SD 0.19; range 0.50–1.32) preoperatively and 0.95 (SD 0.20; range 0.5–1.32) postoperatively (p = 0.3). 17 of 46 patients had a pathological sulcus angle of > 142° (Brattstroem 1964). The mean angle preoperatively was 140° (127–168) and postoperatively it was 142° (131–168) (p = 0.09).

Complications

11 knees had recurrent dislocations after surgery. 8 knees had a single dislocation within 3 months of surgery, and 3 knees had repeated late dislocations. 2 of the 3 knees with repeated dislocations showed Dejour grade-C patellofemoral dysplasia and one showed a Dejour grade-B dysplasia. Internal rotation of the femur and external tibial torsion were normal in these patients.

Discussion

Dislocations of the patella have been reported to occur more often in children and adolescents (Buchner et al. 2005). For first-time patella dislocations, nonoperative management is recommended with early joint motion and quadriceps strengthening after initial long leg casting or bracing (Sillanpaa et al. 2009). Recurrent patella dislocations that fail to respond to nonoperative treatment require operative intervention to prevent chondral damage and subsequent osteoarthritis (Maenpaa et al. 1997a, Barber and McGarry 2008).

In young patients with open physes, surgery in the area of the growth plates could result in premature closure of the physis (Grammont et al. 1985, Nelitz et al. 2011). There have been few studies addressing the long-term outcome of operative treatment of recurrent patella dislocation in immature patients.

In 2009, one of the authors (FS) presented preliminary results of the modified Grammont technique after a mean of 4 years (Schneider and Linhart 2009). In that study, the redislocation rate was 4 out of 36 and the mean Tegner activity score declined to 1.5 points. 7 patients in the present study also took part in the earlier study by Schneider et al. (12 knees) (Schneiderand Linhart 2009). In contrast to that study, we applied stricter inclusion criteria in the present study (see Material and methods).

Several procedures for the operative treatment of recurrent patella dislocations have been reported (Table 3). However, due to the variability of measured parameters, meaningful comparisons between the studies mentioned are not possible. Several studies included adults only, while other studies included a small number of patients. The optimal management of patellofemoral instability in children and adolescents therefore remains unclear. Recent studies have identified the medial patella-femoral ligament (MPFL) as the strongest passive stabilizer of the patella in preventing excessive lateralization (Beasley and Vidal 2004). Reconstruction of the medial femuropatellar ligament (MPFL) is becoming more and more popular (Beasley and Vidal 2004). The femoral approach for the MPFL is close to the distal physis of the femur, with a risk of growth disturbances (Nelitz et al. 2011). Previous studies addressing the outcome of an MPFL reconstruction in immature patients are limited in number, with only short follow-up periods. They may therefore have under-reported potential growth disturbances following surgery (Schottle et al. 2005, Yercan et al. 2011).

Table 3.

Overview of literature

| Author and year | Mean age |

Knees/ patients |

Follow-up (year) |

Technique | Score | Results a | Redislocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vahasarja 1995 | 13 | 57/48 | 4.2 | MIxed b | Insall | E 20, G 20, F 11, P 6 | 13 |

| Schneider et al. 1997 | 16 | ?/17 | 10 | Goldwaith procedure | Bentley | recurrent group: E 20%; G 20%, F 20%, P 10% habitual group: E 43%; G 28%; F 14%; P 14% |

1 |

| Zeichen et al. 1998 | 21 | ?/45c | 6.5 | prox. realignment with | Larsen, | first-time dislocation: E 3, G 10, F 2 | |

| Insall technique | Lauridsen | recurrent dislocation: E 7, G 12, F 10, P 1 | 1 | ||||

| Letts et al. 1999 | 14 | 26/22 | 2.4 | Semi-membranosus | Lysholm, | E 6, G 12, P 4 | 1 |

| tenodesis | Zarins-Rowe | ||||||

| Marsh et al. 2006 | 14 | 30/20 | 6.2 | modified Roux-Goldwaith | Insall | E 26, G 3, F 1 | 0 |

| Ali et al. 2007 | 26 | 36/35 d | 4.3 | proximal arthroscopic | Lysholm | E+G 28, F 4, P 4 | 2 |

| Joo et al. 2007 | 6 | 6/5 | 4.5 | 4 in 1 technique | Kujala | E 5, G 1 | 0 |

| Oliva et al. 2009 | 13 | ?/25 | 3.8 | 3 in 1 technique | Cincinnati, Kujala |

scores increased significantly from pre- to postoperative |

1 |

| Luhmann et al. 2011 | 14 | 27/23 | 5.1 | proximal and/or distal realignment surgery |

Tegner, Lysholm |

mean Tegner 5.4 mean Lysholm 69.3 |

2 |

a E – excellent, G – good, F – fair, and P – poor

b Mixed: lateral release with or without medial reefment and/or Roux–Goldwaith procedure

c 15 first-time dislocations + 30 recurrent dislocations

d 24 dislocations + 12 subluxations

In more than 80% of patients with open physes and recurrent patella dislocations, there are predisposing factors (Dejour et al. 1994, Maenpaa 1996). In particular, torsional abnormalities appear to be more frequent than commonly appreciated. Increased femoral antetorsion in combination with increased lateral tibial torsion might favor patella dislocations in young patients (Airanow et al. 1990). 50 of our patients showed increased internal rotation of the femur and 16 showed increased external rotation of the tibia. These conditions are directly addressed by the modified Grammont procedure. In patients with closed physes who have an abnormal lateral position of the tibial tuberosity, distal bony procedures provide an appropriate alternative, with established success rates (Endres and Wilke 2011). Open apophysis of the tibial tuberosity contraindicates osteotomy at the tibial tubercle, as it has been reported to lead to closure of the physis and genu recurvatum (Grammont 1985, Barber and McGarry 2008). The modified Grammont procedure we used—an exclusively soft-tissue technique—restores the distal re-alignment and preserves the tibial apophysis. In the present study, no growth disturbance occurred. This simple technique provides little operative trauma, allows integrity of the pes anserinus tendons, and gives dynamic positioning of the distal patella tendon. The pre- to postoperative unchanged Blackburne-Peel index indicated that the surgery had no effect on the length of the patella ligament and only medialized it. Early weight bearing is possible, and early movement is even indicated. In contrast, bony distal re-alignment procedures require longer rehabilitation and bear the risk of non-union.

It is well known that patients who undergo stabilizing surgery have a higher incidence of osteoarthritis over time. Arnbjornsson et al. (1992) reported a 75% rate of osteoarthritis at a mean follow-up of 14 years. Sillanpaa et al. reported a severe osteoarthritis rate of 30% after 10 years (Sillanpaa et al. 2011).

A patellar ligament that is fixed too far medially leads to increased medial articular cartilage contact pressure, resulting in an early medial compartment arthritis, especially in patients with genua valga (Kuroda et al. 2001). We modified the original Grammont technique by allowing dynamic positioning of the distal patella tendon. We expected that the patella would find its “ideal” position, reducing deforming forces and minimizing the risk of chondral damage, which may explain the comparably low rate of osteoarthritis (6/58) in our patients.

In the present study, 54 of 65 knees had no more dislocations. None of the 8 patients with a single redislocation required revision surgery. Redislocations occurred in 2 knees with type-C dysplasia according to Dejour et al. (Dejour et al. 1994). For these patients, the simple patellar re-alignment does not appear to be sufficient, and as adults these patients were offered MPFL reconstruction. Notably, more than half of the patients in our study showed a patello-femoral dysplasia, which plays a considerable role in recurrent dislocations (Nelitz et al. 2012). Furthermore, the young age of the patients appears to favor recurrent dislocation (Buchner et al. 2005).

The average Lysholm score in the present study was 82 points, revealing good to very good functional outcome. Redislocations do not appear to worsen clinical function, which is in accordance with the findings of Buchner et al. (2005). Other authors (Maenpaa et al. 1997b, Nikku et al. 1997) also found the discrepancy between a high recurrence rate and good subjective outcome. Buchner et al. (2005) reported a redislocation rate of 10/37 (surgical group) after acute patellar dislocation, with a good subjective outcome in 27/30.

The strengths of our study are the length of follow-up, the low dropout rate, and a uniform technique. Weaknesses of the study include the missing preoperative Lysholm scores for comparison, the lack of a control group, the lack of data on Q-angles, and the lack of additional radiographic measurements.

In summary, we found that a modified Grammont procedure is a feasible method to treat recurrent patella dislocation in skeletally immature patients. However, patients with higher-grade patello-femoral dysplasias (Dejour type C) should be informed that they have a higher risk of redislocation and that additional surgery might be required after skeletal maturity.

References

- Airanow S, Zippel H. Femoro-tibial torsion in patellar instability. A contribution to the pathogenesis of recurrent and habitual patellar dislocations. Beitr Orthop Traumatol. 1990;37(6):311–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S, Bhatti A. Arthroscopic proximal realignment of the patella for recurrent instability: report of a new surgical technique with 1 to 7 years of follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(3):305–11. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt EA, Fithian DC, Cohen E. Current concepts of lateral patella dislocation. Clin Sports Med. 2002;21(3):499–519. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(02)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnbjornsson A, Egund N, Rydling O, Stockerup R, Ryd L. The natural history of recurrent dislocation of the patella. Long-term results of conservative and operative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1992;74(1):140–2. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B1.1732244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber FA, McGarry JE. Patterns of hip rotation range of motion: a comparison between healthy subjects and patients with low back pain. Phys Ther. 1990;70:537–41. doi: 10.1093/ptj/70.9.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber FA, McGarry JE. Elmslie-Trillat procedure for the treatment of recurrent patellar instability. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(1):77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley LS, Vidal AF. Traumatic patellar dislocation in children and adolescents: treatment update and literature review. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2004;16(1):29–36. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200402000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburne JS, Peel TE. A new method of measuring patellar height. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1977;59(2):241–2. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.59B2.873986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brattstroem H. Shape of the intercondylar groove normally and in recurrent dislocation of patella. A clinical and X-ray-anatomical investigation. Acta Orthop Scand (Suppl 68) 1964:1–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner M, Baudendistel B, Sabo D, Schmitt H. Acute traumatic primary patellar dislocation: long-term results comparing conservative and surgical treatment. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15(2):62–6. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000157315.10756.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejour H, Walch G, Nove-Josserand L, Guier C. Factors of patellar instability: an anatomic radiographic study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1994;2(1):19–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01552649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endres S, Wilke A. A 10 year follow-up study after Roux-Elmslie-Trillat treatment for cases of patellar instability. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grammont PM, Latune D, Lammaire IP. Treatment of subluxation and dislocation of the patella in the child. Elmslie technic with movable soft tissue pedicle (8 year review) Orthopade. 1985;14(4):229–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo SY, Park KB, Kim BR, Park HW, Kim HW. The ‘four-in-one’ procedure for habitual dislocation of the patella in children: early results in patients with severe generalised ligamentous laxity and aplasis of the trochlear groove. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2007;89(12):1645–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B12.19398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16(4):494–502. doi: 10.1136/ard.16.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda R, Kambic H, Valdevit A, Andrish JT. Articular cartilage contact pressure after tibial tuberosity transfer. A cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(4):403–9. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290040301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letts RM, Davidson D, Beaule P. Semitendinosus tenodesis for repair of recurrent dislocation of the patella in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999;19(6):742–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann SJ, O’Donnell JC, Fuhrhop S. Outcomes after patellar realignment surgery for recurrent patellar instability dislocations: a minimum 3-year follow-up study of children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31(1):65–71. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e318202c42d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysholm J, Gillquist J. Evaluation of knee ligament surgery results with special emphasis on use of a scoring scale. Am J Sports Med. 1982;10(3):150–4. doi: 10.1177/036354658201000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenpaa H, Lehto M. Patellofemoral osteoarthritis after patellar dislocation. Clin Orthop. 1997a;339:156–62. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199706000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenpaa H, Lehto MU. Patellar dislocation. The long-term results of nonoperative management in 100 patients. Am J Sports Med. 1997b;25(2):213–7. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JS, Daigneault JP, Sethi P, Polzhofer GK. Treatment of recurrent patellar instability with a modification of the Roux-Goldthwait technique. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(4):461–5. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000217711.34492.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant AC, Mercer RL, Jacobsen RH, Cool CR. Roentgenographic analysis of patellofemoral congruence. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1974;56(7):1391–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelitz M, Dornacher D, Dreyhaupt J, Reichel H, Lippacher S. The relation of the distal femoral physis and the medial patellofemoral ligament. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(12):2067–71. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelitz M, Theile M, Dornacher D, Wolfle J, Reichel H, Lippacher S. Analysis of failed surgery for patellar instability in children with open growth plates. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(5):822–8. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1599-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nietosvaara Y, Aalto K, Kallio PE. Acute patellar dislocation in children: incidence and associated osteochondral fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994;14(4):513–5. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199407000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikku R, Nietosvaara Y, Kallio PE, Aalto K, Michelsson JE. Operative versus closed treatment of primary dislocation of the patella. Similar 2-year results in 125 randomized patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1997;68(5):419–23. doi: 10.3109/17453679708996254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikku R, Nietosvaara Y, Aalto K, Kallio PE. Operative treatment of primary patellar dislocation does not improve medium-term outcome: A 7-year follow-up report and risk analysis of 127 randomized patients. Acta Orthop. 2005;76(5):699–704. doi: 10.1080/17453670510041790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva F, Ronga M, Longo UG, Testa V, Capasso G, Maffulli N. The 3-in-1 procedure for recurrent dislocation of the patella in skeletally immature children and adolescents. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(9):1814–20. doi: 10.1177/0363546509333480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmu S, Kallio PE, Donell ST, Helenius I, Nietosvaara Y. Acute patellar dislocation in children and adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2008;90(3):463–70. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F, Linhart W. Behandlung der Patellaluxation im Kindes- und Jugendalter. Arthroskopie. 2009;1(22):60–7. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T, Menke W, Fink B, Ruther W, Schulitz KP. Recurrent dislocation of the patella and the Goldthwait operation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1997;116(1-2):46–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00434100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schottle PB, Fucentese SF, Romero J. Clinical and radiological outcome of medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction with a semitendinosus autograft for patella instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13(7):516–21. doi: 10.1007/s00167-005-0659-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillanpaa PJ, Mattila VM, Maenpaa H, Kiuru M, Visuri T, Pihlajamaki H. Treatment with and without initial stabilizing surgery for primary traumatic patellar dislocation. A prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009;91(2):263–73. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillanpaa PJ, Mattila VM, Visuri T, Maenpaa H, Pihlajamaki H. Patellofemoral osteoarthritis in patients with operative treatment for patellar dislocation: a magnetic resonance-based analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(2):230–5. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1285-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegner Y, Lysholm J. Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clin Orthop. 1985;(198):43–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahasarja V. Prevalence of chronic knee pain in children and adolescents in northern Finland. Acta Paediatr. 1995;84(7):803–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yercan HS, Erkan S, Okcu G, Ozalp RT. A novel technique for reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament in skeletally immature patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131(8):1059–65. doi: 10.1007/s00402-011-1305-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeichen J, Lobenhoffer P, Bosch U, Friedemann K, Tscherne H. Interim results of surgical therapy of patellar dislocation by Insall proximal reconstruction. Unfallchirurg. 1998;101(6):446–53. doi: 10.1007/s001130050294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]