Abstract

Background and purpose

A considerable number of patients who undergo surgery for spinal stenosis have residual symptoms and inferior function and health-related quality of life after surgery. There have been few studies on factors that may predict outcome. We tried to find predictors of outcome in surgery for spinal stenosis using patient- and imaging-related factors.

Patients and methods

109 patients in the Swedish Spine Register with central spinal stenosis that were operated on by decompression without fusion were prospectively followed up 1 year after surgery. Clinical outcome scores included the EQ-5D, the Oswestry disability index, self-estimated walking distance, and leg and back pain levels (VAS). Central dural sac area, number of levels with stenosis, and spondylolisthesis were included in the MRI analysis. Multivariable analyses were performed to search for correlation between patient-related and imaging factors and clinical outcome at 1-year follow-up.

Results

Several factors predicted outcome statistically significantly. Duration of leg pain exceeding 2 years predicted inferior outcome in terms of leg and back pain, function, and HRLQoL. Regular and intermittent preoperative users of analgesics had higher levels of back pain at follow-up than those not using analgesics. Low preoperative function predicted low function and dissatisfaction at follow-up. Low preoperative EQ-5D scores predicted a high degree of leg and back pain. Narrow dural sac area predicted more gains in terms of back pain at follow-up and lower absolute leg pain.

Interpretation

Multiple factors predict outcome in spinal stenosis surgery, most importantly duration of symptoms and preoperative function. Some of these are modifiable and can be targeted. Our findings can be used in the preoperative patient information and aid the surgeon and the patient in a shared decision making process.

Decompressive surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis is the most frequently performed spine operation in many countries (Weinstein et al. 2006, Strömqvist et al. 2009). However, one third of patients are not satisfied with the outcome because of residual leg and back pain, inferior function, and poor health-related quality of life (Katz et al. 1995, Airaksinen et al. 1997, Jönsson et al. 1997, Jansson et al. 2009, Strömqvist et al. 2009, Hara et al. 2010).

2 recent randomized studies have shown surgery to be superior to nonoperative treatment in lumbar spinal stenosis (Malmivaara et al. 2007, Weinstein et al. 2008), but many patients improve without surgical treatment (Malmivaara et al. 2007). The question remains as to who benefits most from surgery. Identification of prognostic factors that can aid in selection of patients for surgery is therefore important. Prognostic factors in lumbar spinal stenosis surgery have been studied, but they are not well defined (Turner et al. 1992, Aalto et al. 2006). Aalto et al. (2006) reviewed studies of lumbar spinal stenosis surgery and found that only 21 studies of 885 were of sufficient quality to merit identification of prognostic factors. The main reason for exclusion was a retrospective study design and a limited number of predictors. Cardiovascular and overall comorbidity, disorders influencing walking ability, self-rated health, income, severity of central stenosis, and severity of scoliosis were found to be predictors of outcome, but no single study could identify more than one of these predictors. More recently, smoking, depression, psychiatric illness, and high body mass index have been found to be predictive of negative outcome, as have long duration of symptoms and preoperative resting numbness (Ng et al. 2007, Hara et al. 2010, Athiviraham et al. 2011, Radcliff et al. 2011, Sandén et al. 2011, Sinikallio et al. 2011).

Cross-sectional imaging (most often MRI) has an important role in confirming the diagnosis of spinal stenosis, and is essential for surgical planning. Even so, the prognostic value of the narrowness of the dural sac area is not well established (Jönsson et al 1997, Amundsen et al. 2000, Yukawa et al. 2002). Studies incorporating both imaging and patient-related factors in a systematic way have been exceedingly rare (Amundsen et al. 2000, Yukawa et al. 2002).

We used patient data from the Swedish Spine Register protocol (Strömqvist et al. 2009) and MRI measurements of central dural sac area, multilevel stenosis, and spondylolisthesis to find predictors of outcome in terms of function, HRLQoL, and leg and back pain after decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis.

Patients and methods

109 consecutive patients from our primary catchment area who had been diagnosed and operated for central spinal stenosis with decompressive surgery using facet joint-sparing technique were included in the study (Table 1). All of these patients were part of the Swedish Spine Register database which is based at our institution.

Table 1a.

Patient demographics

| Men / women | 56 / 53 |

| Mean age | 71 (10) |

| Age groups (years) | |

| 30–50 | 2 |

| 50–60 | 14 |

| 60–70 | 21 |

| 70–80 | 53 |

| > 80 | 19 |

| Mean dural sac area (mm2) (SD) | 43 (17) |

| Multilevel stenosis | 54 |

| Spondylolisthesis, all grade I | 35 |

| Smokers | 9 |

Selection of patients for surgery was based on symptoms typical of central spinal stenosis including neurogenic claudicatio, leg and back pain, or any combination of these. The spinal surgeon and a neuroradiologist reviewed the MRI findings, and if the clinical findings and MRI findings corresponded, surgery was offered. Only patients for whom decompressive surgery without fusion was judged by the surgeon to be appropriate were included in the study. This included 35 patients with low-grade degenerative spondylolisthesis, all with typical symptoms of central spinal stenosis. Patients with high-grade spondylolisthesis, low-grade spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis, instability catch, and high-level of back pain compared to leg pain had concomitant fusion and were therefore excluded.

The operations were performed by 5 surgeons specialized in spine surgery; all had over 20 years experience in degenerative spine surgery. All patients were diagnosed and operated at Lund University Hospital, Sweden between 2000 and 2007. Preoperatively and at the 1-year follow-up, all patients completed the self-administred Swedish Spine Register protocol (Strömqvist et al. 2009) including: the EQ-5D, the Oswestry disability index, estimated walking distance (1 = < 100 m, 2 = 100–499 m, 3 = 500–1,000 m, and 4 = > 1,000 m), and leg and back pain (VAS). A 100-mm VAS scale was used. The Oswestry disability index was added to the Swedish Spine Register protocol in 2003. In addition, global assessment of outcome was assessed at follow-up, as was estimated reduction in leg and back pain. The response rate for the different pre- and postoperative outcomes varied (Table 1).

Table 1b.

Patient demographics

| Outcome assessment parameters, mean (SD) |

Preoperatively | At 1-year follow-up |

p-value | Pre- and postoperative data available for number of patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leg pain (VAS) | 68 (24) | 37 (32) | < 0.001 | 76 |

| Back pain (VAS) | 54 (28) | 36 (30) | < 0.001 | 77 |

| EuroQol-5D | 0.41 (0.29) | 0.60 (0.26) | < 0.001 | 74 |

| Oswestry disability index | 46 (15) | 31 (20) | < 0.001 | 57 |

| Self-estimated walking distance | 103 | |||

| < 100 m | 51 | 30 | < 0.001 | |

| ≥ 100 m | 54 | 76 | 0.001 |

Paired t-test was used.

Evaluation of the magnetic resonance imaging

Preoperative MRI was performed on all patients in the supine position, and was evaluated by the surgeon and a neuroradiologist. All patients had central canal stenosis with or without recess encroachment. The dural sac area and grade of spondylolisthesis were separately measured by one of the authors (XPK, who was not involved in treatment of the patients). A subset of 20 randomly selected patients was also analyzed by 2 of the other authors (BJ and BS), and interobserver analyses were performed; for detailed information, see Sigmundsson et al. (2011). The dural sac area at the disc levels in the lumbar spine was measured on axial T1 images with the region-of-interest function on a dedicated workstation using SECTRA software (Sectra Imtec AB, Linköping, Sweden). Spondylolisthesis was defined as more than 3 mm of anterior translation on the supine MRI and the grade of spondylolisthesis was defined according to Meyerding (1932).

Ethics

The patients were included in the Swedish Spine Register, and as such they had given informed consent for participation in this study. The Swedish Spine Registry is the property of the Swedish Society for Spinal Surgeons and is funded by the National Board of Health and Welfare (Strömqvist et al. 2009).

Statistics

We used STATA 10 statistical software. Normality of data was tested with the Shapiro-Wilk test for normal data. Paired t-test was used for analysis of preoperative and postoperative values of all outcome parameters except EQ-5D. When no assumption of a normal distribution could be made, non-parametric tests were used (Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance, test for trend across ordered group). The 95% confidence interval (CI) for difference in medians was calculated with a stratified bootstrap test using the R server at www.rcsyd.se. Spearman’s rank correlation was used to assess the correlation between preoperative EQ-5D and leg and back pain at 1-year follow-up. Multivariable regression analyses were performed to calculate the relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. We did multivariable analysis for variation in outcome for leg and back pain, EQ-5D, and short postoperative walking distance. In our model, we controlled for age, preoperative leg and back pain, preoperative walking distance, duration of leg and back pain, multilevel stenosis, and spondylolisthesis. Values of p < 0.05 were regarded as being statistically significant.

Results

Imaging-related outcome

Patients with spondylolisthesis were older and more often had multilevel stenosis and narrower dural sac area. Despite this, there was no statistically significant difference in outcome between the groups of patients with and without spondylolisthesis (Table 2). Some clinical difference was, however, observed as patients with spondylolisthesis had lower levels of leg and back pain despite more pronounced morphological disease in terms of MRI findings. Patients operated for multilevel stenosis had lower leg pain scores on the VAS scale at follow-up than patients with single-level disease (p = 0.06). Pain relief in terms of back pain was associated with more constricted dural sac areas; this was, however, not the case for leg pain (Figure 1, see Supplementary data). A small statistically significant correlation between leg pain at follow-up and the most constricted dural sac area was found, as narrow dural sac area was associated with lower leg pain (Figure 2, see Supplementary data). No other statistically significant relationships between imaging and outcome were found.

Table 2.

MRI characteristics, HRLQoL, and functional status in patients with and without spondylolisthesis at 1-year follow-up

| Age | Dural sac area (mm2) |

Multilevel stenosis |

EuroQol-5D | Oswestry disability index |

Estimated walking distance a |

Leg pain, VAS b |

Back pain, VAS b |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With olisthesis | 75 (7) | 38 (16) | 1.8 (0.8) | 0.62 (0.23) | 29 (15) | 2.3 (1.1) | 29 (26) | 33 (30) |

| n = | 35 | 35 | 35 | 30 | 21 | 35 | 31 | 32 |

| Without olisthesis | 69 (10) | 45 (17) | 1.5 (0.8) | 0.59 (0.27) | 31 (22) | 2.5 (1.2) | 41.1 (35) | 37 (30) |

| n = | 74 | 74 | 74 | 58 | 43 | 71 | 67 | 68 |

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.04 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| 95% CI for difference in medians c | –9 to –1 | 1 to 19 | –1 to 1 | –0.11 to 0.04 | –12 to 10.1 | –1 to 1 | –17 to 44 | –22 to 29 |

Mann-Whitney test. Standard deviations in parentheses.

a Estimated walking distance: 1 = < 100 m, 2 = 101–499 m, 3 = 500–1,000 m, and 4 = > 1,000 m.

b VAS: visual analog scale.

c Stratified bootstrap test for difference in medians.

Patient-related outcome

Global assessment and outcome parameters (Table 3). Patients who were satisfied at the 1-year follow-up had an improved score in all outcome parameters. Undecided patients improved their walking distance but the improvement in leg or back pain was not statistically significant. Dissatisfied patients had similar pre- and postoperative values for outcome parameters.

Table 3.

Patient satisfaction (global assessment) at 1-year follow-up in relation to pre-and postoperative HRLQoL, functional status, and pain

| EuroQol-5D (SD) |

Oswestry disability index (SD) |

Leg pain VAS (SD) |

Back pain VAS (SD) |

Estimated walking distance (SD) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PO | FU | p-value | PO | FU | p-value | PO | FU | p-value | PO | FU | p-value | PO | FU | p-value | |

| Satisfied | 0.44 | 0.66 | < 0.001 | 45 | 22 | < 0.001 | 68 | 26 | < 0.001 | 54 | 24 | < 0.001 | 1.8 | 2.8 | < 0.001 |

| n 67 (65%) | (0.30) | (0.24) | (15) | (14) | (24) | (28) | (28) | (24) | (0.8) | (1.1) | |||||

| n = | 49 | 58 | 36 | 40 | 51 | 61 | 50 | 62 | 65 | 67 | |||||

| Undecided | |||||||||||||||

| n 25 (24%) | 0.33 | 0.49 | 0.007 | 50 | 43 | 0.2 | 70 | 58 | 0.08 | 57 | 53 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 0.005 |

| (0.28) | (0.25) | (17) | (21) | (21) | (30) | (28) | (30) | (0.8) | (1.1) | ||||||

| n = | 20 | 21 | 14 | 17 | 21 | 23 | 22 | 24 | 24 | 25 | |||||

| Dissatisfied | |||||||||||||||

| n 11 (11%) | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.3 | 40 | 50 | 0.1 | 52 | 55 | 0.9 | 53 | 64 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| (0.25) | (0.27) | (11) | (21) | (26) | (32) | (25) | (25) | (0.5) | (0.9) | ||||||

| n = | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 11 | 10 | 11 | |||||

| pa | 0.2 | < 0.001 | 0.5 | < 0.001 | 0.2 | < 0.001 | 0.9 | < 0.001 | 0.2 | < 0.001 | |||||

| p b | 0.75 | < 0.001 | 0.45 | < 0.001 | 0.15 | < 0.001 | 0.93 | < 0.001 | 0.10 | < 0.001 | |||||

PO: preoperative; FU: 1-year follow-up; ODI: ; VAS: visual analog scale; SD: standard deviation.

pa: Kruskall Wallis equality of populations rank test; p b: test for trend across ordered groups.

Paired t-test was used to compare outcome measures within global assessment for change in Oswestry disability index, leg and back pain, and estimated walking distance. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test was used for change in EQ-5D, as this variable did not have a normal distribution according to the Shapiro-Wilk test.

Sex, age, smoking, and outcome. No statistically significant differences in outcome parameters were found between the sexes. When grouped into 5 age groups, 30–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and > 80 years old, an inferior outcome in terms of postoperative walking distance was found (p = 0.009) with increasing age. No other statistically significant relationship between patient age and outcome was found. 9 patients were smokers. No statistically significant differences were found in outcome parameters between smokers (n = 9) and non-smokers (n = 100).

Preoperative consumption of analgesics. 17 never used some type of analgesic, 54 sometimes did, and 37 did regularly. Patients taking analgesics preoperatively—either intermittently or regularly—respectively reported 20-point (CI: 3–37, p = 0.02) and 21-point (CI: 3–38, p = 0.02) higher scores on the VAS scale at 1-year follow-up than those not taking analgesics preoperatively.

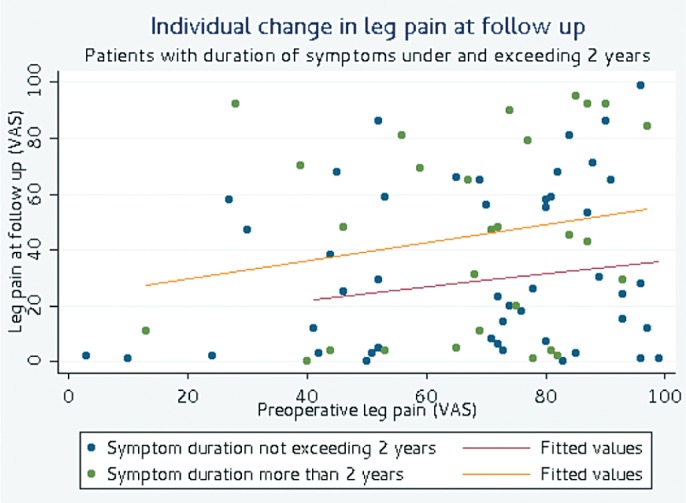

Preoperative duration of leg and back pain (Tables 4–6 and Figure 3; for Table 6, see Supplementary data). Duration of leg and back pain of 2 years and longer was associated with inferior outcome and low patient satisfaction. Patients with duration of leg pain exceeding 2 years had statistically significantly higher leg and back pain levels and inferior function in terms of ODI and lower HRLQoL (EQ-5D). Patients with the same duration of back pain reported inferior HRLQoL (EQ-5D).

Table 4.

Duration of leg pain and outcome measures at 1-year follow-up

| Duration of pain pre-operatively |

EuroQol-5D | Oswestry disability index |

Leg pain | Back pain | Walking distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up to 2 years | 0.65 (0.24) | 25 (17) | 31 (29) | 31 (30) | 2.8 (1.2) |

| n = | 52 | 36 | 57 | 58 | 62 |

| Over 2 years | 0.52 (0.51) | 38 (22) | 47 (35) | 43 (29) | 1.1 (1.1) |

| n = | 36 | 28 | 41 | 42 | 44 |

| p-value | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.002 |

| 95% CI for difference in medians a | –0.04 to 0.34 | –24 to 2 | –52 to –3 | –41 to –0.5 | –1 to 1 |

Two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Standard deviation in parentheses.

a Stratified bootstrap test for difference in medians.

Table 5.

Duration of back pain and outcome measures at 1-year follow-up

| Duration of pain pre-operatively |

EuroQol-5D | Oswestry disability index |

Leg pain | Back pain | Walking distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up to 2 years | 0.64 (0.27) | 28 (20) | 33 (31) | 32 (31) | 2.6 (1.1) |

| n = | 43 | 27 | 48 | 49 | 52 |

| Over 2 years | 0.54 (0.25) | 35 (19) | 44 (33) | 40 (30) | 2.2 (1.2) |

| n = | 42 | 34 | 46 | 47 | 50 |

| p-value | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.06 |

| 95% CI for differenc in medians a | –0.03 to 0.1 | –22 to 6 | –41 to 14 | –37 to 9 | 0 to 1.5 |

Two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Standard deviation in parentheses.

a Stratified bootstrap test for difference in medians.

Figure 3.

Individual change in leg pain at follow-up.

Self-estimated walking distance (Table 7, see Supplementary data). Patients with shorter preoperative walking distances tended to have higher levels of leg pain at follow-up (p = 0.04). Patients with a short preoperative self-estimated walking distance (< 100 m) were less satisfied with their outcome at follow-up, although not statistically significantly so.

Preoperative quality of life parameters and outcome. Low preoperative EQ-5D scores predicted high postoperative pain levels for both leg pain (rs = –0.32, p = 0.006) and back pain (rs = –0.36, p = 0.004).

Complications and reoperations. 2 patients suffered dural tears that were repaired during surgery. No reoperations were performed within the 1-year follow-up period.

Patient- and imaging-related factors

Multivariable regression analysis was performed for variation in outcome for leg pain (VAS). We controlled for age, preoperative leg and back pain, preoperative walking distance, and duration of leg and back pain. Preoperative self-estimated walking distance of > 1,000 m was associated with decrease in leg pain, corresponding to 72 points on the VAS scale (CI: –107 to –37, p < 0.001). Multilevel stenosis and spondylolisthesis were also associated with reduction in leg pain at the 1-year follow-up; 15 points for multilevel stenosis (CI: –30 to –0.2, p = 0.05) and 16 points for concomitant spondylolisthesis (CI: –31 to –1, p = 0.04).

In the multivariable regression analysis, controlling for the factors mentioned above, back pain at follow-up increased 0.5 points (CI: 0.06–1.0, p = 0.03) on the VAS scale per 1 mm2 in the central dural sac area.

Quality of life in terms of EQ-5D at follow-up correlated with the preoperative walking distance in the multivariable analysis, as patients with a preoperative walking distance of between 100–500 m and > 1,000 m had higher EQ-5D scores than those with a preoperative walking distance of < 100 m. This can be explained further, as patients with a self-estimated walking distance of between 100 m and 500 m had a 0.1-point (CI: 0.009–0.3, p = 0.04) higher EQ-5D score than patients with a walking distance of < 100 m. Patients who rated their preoperative walking distance as over 1,000 m had a 0.3-point (CI: 0.06–0.6, p = 0.05) higher EQ-5D score at follow-up.

Long self-estimated postoperative walking distance (> 100 m) at follow-up was influenced by the long self-estimated preoperative walking distance (OR = 9, CI: 2–54, p = 0.01).

Discussion

This study identified patients with good preoperative function and HRLQoL, short duration of symptoms, narrow dural sac area, spondylolisthesis, and absence of consumption of analgesics to be most likely to achieve a good outcome after decompression for spinal stenosis. An example of this is that patients having leg pain less than 2 years and self estimated walking distance of > 100 m are almost 3 times more likely to be satisfied with operative outcome at 1-year follow-up compared with patients having leg pain exceeding 2 years and very poor preoperative walking distance (< 100 m).

An important finding was the negative effect of long duration of symptoms. Longstanding pain and loss of function in these elderly patients may be difficult to treat. Duration of symptoms is a potentially modifiable factor by giving better information to patients, doctors and healthcare policy makers for earlier diagnosis and intervention. Two meta-analyses exploring prognostic factors in spinal stenosis surgery did not find that duration of symptoms was a significant factor (Turner et al. 1992, Aalto et al. 2006), and a previous study from our institution found a trend of inferior outcome in patients with duration of symptoms exceeding 4 years (Jönsson et al. 1997). Recent studies have shown duration of symptoms to be an important prognostic factor. Ng et al. (2007) showed that patients with a duration of symptoms of less than 3 years to have a better prognosis than those with a longer duration of symptoms. In an analysis from the SPOR trail, Radcliff et al. (2011) found that patients treated both operatively and nonoperatively with a symptom duration of ≥ 1 year improved less than those with a shorter duration of symptoms. There have been few long-term studies on the outcome of surgery for spinal stenosis, but in a prospective study, Amundsen et al. (2000) did not find that duration of symptoms had any influence on outcome after a 10-year follow-up. Thus, there is contradicting information in the literature about the predictive value of the duration of symptoms preoperatively.

In addition to the negative psychological effect of longstanding pain and inferior function on the patient, chronic spinal nerve compression has been shown in experimental studies to initiate demyelinization and change of the phenotype of the nerve, perhaps limiting the ability to improve neuronal function (Gupta et al. 2004, Chao et al. 2008). Compression of the cauda equina can also reduce blood flow to spinal nerves (Olmarker et al. 1989).

It is important, however, to keep in mind the natural history of spinal stenosis; pain and function vary over time (Johnsson et al. 1992). Thus, if surgery is performed very early, some patients will probably be operated who would also improve without surgery. In a randomized study by Malmivaara et al. (2007), about half of the patients who were assigned to nonoperative treatment experienced improvement during the follow-up period. It is important for the spinal surgeon to discuss these facts with the patient and the results of our study can provide some help in that discussion.

Another important finding is the negative prognostic value of poor preoperative function, as patients with very low functional ability are less satisfied at 1-year follow-up and gain less in terms of pain and HRLQoL (EQ-5D). This implies a true risk of over-treatment as some—especially older—patients can accept a low level of function and, as mentioned earlier, the natural history of spinal stenosis is quite variable. The impact of comorbidities on function should also be weighed in, as a patient with severe heart insufficiency or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease would probably experience limited gain in function by having a decompression for spinal stenosis.

We found no difference in outcome in patients with and without spondylolisthesis when compared group wise; however, having spondylolisthesis predicted significant reductions in leg pain in the multivariable analysis, as patients with spondylolisthesis had reduced leg pain (by 16 mm) on the VAS scale. Admittedly, this study was not designed to answer the question of how to treat spondylolisthesis, but patients in the spondylolisthesis group were older and had smaller dural sac area—and despite this, significant pain reduction was observed in the multivariable analysis. No patients were fused in the spondylolisthesis group, as all the patients had low-grade spondylolisthesis with essentially the same clinical presentation as the patients with spinal stenosis without spondylolisthesis. Previous studies have often included patients with and without concomitant spondylolisthesis subsequently treated with decompression with or without fusion (Yukawa et al. 2002, Athiviraham et al. 2011), perhaps making the cohorts from these studies more heterogenous and evaluation of prognostic factors more difficult. We believe that it was justified to include patients with low-grade slip, in our study as the clinical syndrome is essentially the same.

Change in intensity of back pain correlated with the narrowness of the dural sac area (patients with smaller dural sac area tended to improve more). The narrowness of the dural sac area only explains a small proportion (5%) of the improvement in back pain, however. Also, patients with large dural sac areas had higher levels of leg pain at follow-up. Some earlier studies have also shown that patients with more severe compression of the cauda equina improve more (Herno et al. 1994, Aliashkevich et al. 1999). However, the correlation between symptoms and the dural sac area has been considered to be poor. Boden et al. (1990) showed that 20% of asymptomatic subjects over 60 years old had spinal stenosis on MRI. More recently, Haig et al. (2007) showed that imaging could not differentiate symptomatic individuals from asymptomatic individuals. Yukawa et al. (2002) showed that the severity of central canal narrowing at a single level did not appear to limit the postoperative improvement in functional and patient-reported outcome. Recently, Kanno et al. (2012) also showed a correlation between severity of symptoms preoperatively and dural sac area on an axially loaded MRI in patients planned for surgery. Also, in a surgical cohort, Ogikubo et al. (2008) showed that dural sac area is a powerful predictor of preoperative walking ability, pain, and HRLQoL. In their 10-year follow-up study, Amundsen et al. (2000) could not establish a relationship between the severity of the stenosis and outcome. Also, 3 other recent studies have failed to show any relationship between preoperative symptoms and MRI findings (Sirvanci et al. 2008, Zeifang et al. 2008, Sigmundsson et al. 2011). Barz et al. (2010) have shown that packed nerve roots (positive sedimentation sign) occur consistently in spinal stenosis.

In many countries, decompressive surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis is the most commonly performed spinal operation. The surgical technique is well established, but indications for surgery, diagnosis, and imaging are not well defined—with considerable geographical variation (Bederman et al. 2011). After surgery, most patients improve in function, pain, and quality of life, and surgical treatment has recently been shown to be superior to nonoperative treatment (Malmivaara et al. 2007, Weinstein et al. 2008). Despite this, many patients have residual symptoms and HRQoL inferior to that of the background population (Strömqvist et al. 2009, Jansson et al. 2009). The results of our study can be used to improve patient information and selection of patients for surgery.

Some of the factors known to have prognostic value could not be included in our study: most importantly, depression (Sinikallio et al. 2011), smoking (Sandén et al. 2011), and BMI (Athivariham et al. 2011). In our opinion, the most important factors for prediction of outcome are the clinical findings that most often lead to surgery, i.e. leg pain, back pain, and preoperative walking distance. Our cohort of patients was elderly with high pain levels, inferior function, low HRLQoL, and very narrow central dural sac area. All these factors can be used to reduce the surgeon selection bias.

Our analysis has identified multiple predictors of outcome in a well-described patient database using both patient- and imaging-related factors with a prospective follow-up. In addition, the study has identified modifiable predictors of outcome, thus possibly enabling improvement in patient care.

We believe that the results of our study can be included in the preoperative patient information as an aid for the patient and the surgeon in shared decision-making. Some caution must, however, be advocated in generalizing the results from a single center cohort to broader surgical practice, as surgeons elsewhere would perhaps treat these patients differently and this relates mainly to our patients with concomitant spondylolisthesis. Another concern is the lack of a control group, as we do not know whether the predictors identified in our cohort would predict the same outcome in patients not undergoing surgery or undergoing different types of surgery.

Acknowledgments

FGS: collected and analyzed the data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript. XPK: collected and analyzed the data and measured all the MRIs. BJ and BS: collected data, operated on some of the patients, and revised the manuscript.

We thank Jonas Ranstam for advice on statistics. We also thank the Greta and Johan Kock Foundation and the Erik and Angelica Sparre Research Foundation for funding.

No competing interests declared.

Supplementary data

Tables 6 and 7, and Figures 1 and 2 are available at our website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 5277.

References

- Aalto TJ, Malmivaara A, Kovacs F, Herno A, Alen M, Salmi L, et al. Preoperative predictors for postoperative clinical outcome in lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2006;31:E648–E663. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000231727.88477.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airaksinen O, Herno A, Turunen V, Saari T, Suomlainen O. Surgical outcome of 438 patients treated surgically for lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1997;22(19):2278–82. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199710010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amundsen T, Weber H, Nordal HJ, Magnaes B, Abdelnoor M, Lilleås F. Lumbar spinal stenosis: Conservative or surgical management ? A prospective 10-year study. Spine. 2000;25(11):1424–36. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200006010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliashkevich AF, Kristof RA, Schramm J, Brechtelsbaner D. Does additional discectomy and the degree of dural sac compression influence the outcome of decompressive surgery for spinal stenosis ? Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1999;141:1273–80. doi: 10.1007/s007010050430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athiviraham A, Wali ZA, Yen D. Predictive factors influencing clinical outcome with operative management of spinal stenosis. Spine J. 2011;11:613–7. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barz T, Melloh M, Staub LP, Lord SJ, Lange J, Röder C P, et al. Nerve root sedimentation sign: evaluation of a new radiological sign in lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2010;35(8):892–7. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c7cf4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bederman SS, Coyte PC, Kreder HJ, Mahomed NN, McIsaac WJ, Wright JG. Who’s in the driver’s seat? The influence of patient and physician enthusiasm on regional variation in degenerative lumbar spinal surgery: a population-based study. Spine. 2011;36(6):481–9. doi: 10.1097/brs.0b013e3181d25e6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1990;72:403–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao T, Pham K, Steward O, Gupta R. Chronic nerve compression injury induces a phenotypic switch of neurons within the dorsal root ganglia. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506(2):180–93. doi: 10.1002/cne.21537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Rowshan K, Chao T, Mozaffar T, Steward O. Chronic nerve compression induces local demyelination and remyelination in a rat model of carpal tunnel syndrome. Exp Neurol. 2004;187(2):500–8. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haig AJ, Geisser ME, Tong HC, Yamakawa KS, Quint DJ, Hoff JT, et al. Electromyographic and magnetic resonance imaging to predict lumbar spinal stenosis, low-back pain, and no back symptoms. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007;89(2):358–66. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara N, Oka H, Yamazaki T, Takeshita K, Murakami M, Hoshi K, et al. Predictors of residual symptoms in lower extremities after decompression surgery on lumbar spinal stenosis. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(11):1849–54. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1374-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herno A, Airaksinen O, Saari T, Miettinen H. The predictive value of preoperative myelography in lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1994;19:1335–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199406000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson KA, Nemeth G, Granath F, Jönsson B, Blomqvist P. Health-related quality of life (EQ-5D) before and one year after surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009;91:210–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B2.21119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson KE, Rosen I, Uden A. The natural course of lumbar spinal stenosis. Clin Orthop. 1992;(279):82–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson B, Annertz M, Sjöberg C, Strömqvist B. A prospective and consecutive study of surgically treated lumbar spinal stenosis. Part II: Five-year follow-up by and independent observer. Spine. 1997;22(24):2938–44. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199712150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno H, Ozawa H, Koizumi Y, Morozumi N, Aizawa T, Kusakabe T, et al. Dynamic change of dural sac cross-sectional area in axial loaded magnetic resonance imaging correlates with the severity of clinical symptoms in patients with lumbar spinal canal stenosis. Spine. 2012;37(3):207–13. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182134e73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Brick GW, Grobler LJ, Weinstein JN, Fossel AH, et al. Clinical correlates of patient satisfaction following laminectomy for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1995;10:1155–60. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199505150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmivaara A, Slatis P, Heliovaara M, Sainio P, Kinnunen H, Kankare J, et al. Surgical or nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis ? A randomized controlled trail. Spine. 2007;32:1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000251014.81875.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerding HW. Spondylolisthesis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1932;54:371–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ng LC, Tafazal S, Sell P. The effect of duration of symptoms on standard outcome measures in the surgical treatment of spinal stenosis. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:199–206. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0078-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogikubo O, Forsberg L, Hansson T. The relationship between the cross-sectional area of the cauda equina and preoperative symptoms in central lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2008;32(13):1423–8. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318060a5f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmarker K, Rydevik B, Holm S, Bagge U. Effects of experimental graded compression on blood flow in spinal nerve roots. A vital microscopic study on the porcine cauda equina. J Orthop Res. 1989;7(6):817–23. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100070607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radkliff K, Rihn J, Hilibrand A, DiIoro T, Tosteson T, Lurie J, et al. Does duration of symptoms in patients with spinal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis affect outcomes? Analysis of the Spine Outcomes Research Trial. Spine. 2011 doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182341edf. E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandén B, Försth P, Michaëlsson K. Smokers show less improvement than nonsmokers two years after surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: a study of 4555 patients from the Swedish spine register. Spine. 2011;36:1059–64. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e92b36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmundsson FG, Kang XP, Jönsson B, Strömqvist B. Correlation between disability and MRI findings in lumbar spinal stenosis. A prospective study of 109 patients operated on by decompression. Acta Orthop. 2011;82(2):204–10. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.566150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinikallio S, Aalto T, Airaksinen O, Lehto SM, Kröger H, Viinamäki H. Depression is associated with a poorer outcome of lumbar spinal stenosis surgery: a two-year prospective follow-up study. Spine. 2011;36:677–82. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181dcaf4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirvanci M, Bhatia M, Ganiyusufoglu KA, Duran C, Tezer M, Ozturk C, et al. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis: correlation with Oswestry Disability Index and MR imaging. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:679–85. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0646-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strömqvist B, Fritzell P, Hägg O, Jönsson B. The Swedish Spine Register: development, design and utility. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:S294–S304. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1043-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JA, Ersek M, Herron L, Deyo R. Surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. Attempted meta-analysis of the litterature. Spine. 1992;17(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Olson P, Bronner KK, Fisher ES, Morgan TS. United States’ trends and regional variations in lumbar spine surgery:1992-2003. Spine. 2006;31(23):2707–14. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000248132.15231.fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, Tosteson AN, Blood E, Hanscom B, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:794–810. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yukawa Y, Lenke LG, Tenhula J, Bridwell KH, Riew KD, Blanke K, et al. A comprehensive study of patients with surgically treated lumbar spinal stenosis with neurogenic claudication. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2002;84:1954–9. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeifang F, Schiltenwolf M, Abel R, Morandi B. MR imaging parameters in patients with symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2008;9:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.