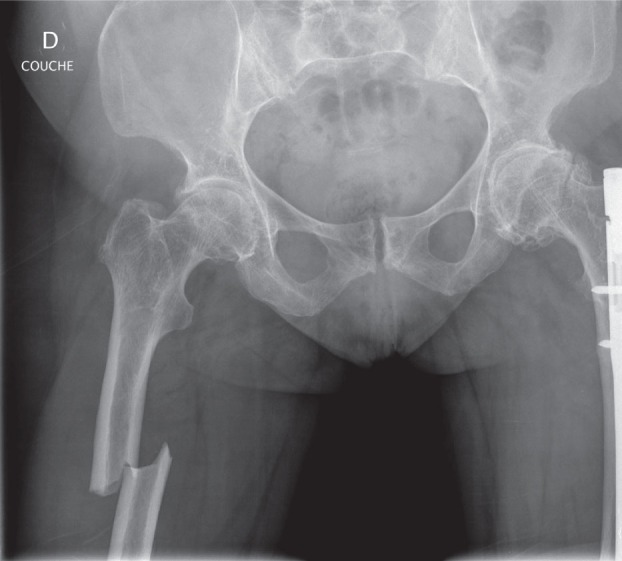

A 75-year-old woman presented with acute pain and deformity of her right lower extremity after a fall from standing height. She had suffered from diffuse pain in the right thigh for 4 months, which had begun after some physical exercise with no trauma. Radiographs revealed an atypical fracture of the right femoral shaft, short oblique, with thickening of the entire lateral cortex (9.3 mm as compared to 7.2 mm at the same level on the contralateral nailed femur) and localized cortical reaction at the level of the fracture (Figure).

Figure.

The atypical fracture of the right femur.

The patient had been diagnosed in childhood with a familial form of osteogenesis imperfecta caused by a de novo mutation. Her parents and siblings had no evidence of bone fragility, but 5 of her 6 children had had multiple fractures starting in childhood, associated with typical clinical signs of type-I collagen abnormalities (Rauch and Glorieux 2004).

Since childhood, our patient had sustained at least 35 fractures, all of which had healed within a normal period of time. The first to be documented was a femoral fracture at the age of 2, followed by many others involving tibia, radius, ulna, humerus, fingers and toes, bilaterally, until the age of 12. From 12 to 27 years of age there were no fractures reported. At the age of 27 the patient had sustained a wrist fracture, and at the age of 35 she had presented with multiple vertebral compression fractures after falling from a tree. More recent events included a high-energy left midshaft femoral fracture during sports at the age of 62, followed by a fracture of the great toe when she was 71.

Because of multiple fractures and osteoporosis (the femoral neck T-score dropped to –2.8 standard deviation when she was 72), she had been administered alendronate (70 mg/week) for the following 3 years, together with calcium and vitamin D supplements (Calcimagon-D3 2 tablets/day). Prior to that, she had been on estrogen replacement therapy (Estraderm day patch) for 13 years. Efficacy of treatment was determined by repeated densitometric evaluations and bone resorption level measurements; the deoxypyridinoline/creatinine ratio was 11 when she was 68 years old, 17 at the age of 72, and 12 one year later (normal range: 8–20).

The patient’s femoral fracture was stabilized with an intramedullary nail. Her postoperative course was uneventful and she was discharged 12 days after surgery. At 1-year follow-up, the fracture was well healed. Alendronate was discontinued a few weeks after the atypical fracture.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of an atypical femoral fracture in a patient with osteogenesis imperfecta who has been treated with bisphosphonates. The clinical and radiographic presentation is compatible with all 5 major features described by the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR) task force, and 4 of the minor features also (Shane et al. 2010). In particular, the fracture was preceded by thigh pain. Despite the high number of recurrent fractures, the femur was involved only once prior to this most recent episode, but this involved the contralateral femur and was a result of high-energy trauma. The patient started on alendronate therapy and a good response was observed with an increase in bone mineral density of the lumbar spine and femoral neck. In addition, the indices of bone resorption decreased over the same time period. While no typical osteoporotic fractures had occurred since initiation of bisphosphonate, the patient developed an atypical femoral fracture after 3 years of treatment. It is therefore conceivable that the reduction in bone turnover together with the increase in bone stiffness may have avoided typical osteoporotic fractures while favoring the accumulation of microdamage at the point of maximal stress (Pauwels 1948), thus contributing to the development of an insufficiency fracture (Mashiba et al. 2001, 2005).

Nevertheless, the most obvious factor that could have contributed to the occurrence of this stress fracture is the osteogenesis imperfecta itself, and this has been reported (Shabat 2000). On the other hand, although partially improved with bisphosphonate treatment, the osteoporosis could have been responsible—as it may contribute to fractures in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta (Bornemann et al. 1987). In addition, there may be some phenotypic and genotypic overlap between mild osteogenesis imperfecta and postmenopausal osteoporosis (Spotila et al. 1991).

Another possible explanation would be a negative interaction between all three factors: a type-I collagen abnormality, osteoporosis, and bisphosphonate. The latter possibly alters collagen maturity and crosslinking in newly formed bone (Durchschlag et al. 2006). However, bisphosphonates have been used successfully in the treatment of osteogenesis imperfecta in children and in young adults (Phillipi et al. 2008), resulting in a 14–31% decrease in the rate of fracture, an increase in height, reduced bone pain, and better quality of life (Adami et al. 2003, Sakkers et al. 2004, Gatti et al. 2005, Letocha et al. 2005, Seikaly et al. 2005, DiMeglio and Peacock 2006). These observations have not been confirmed in older patients, probably due to the low prevalence of osteogenesis imperfecta in adults, which is reported to be 31 cases per 106 individuals (Wekre et al. 2010).

While atypical femoral fractures have mainly been reported in patients taking bisphosphonates (Schilcher et al. 2011, Meier et al. 2012), certainly not all the patients who are treated this way develop these stress fractures. One or more co-factors may be involved, leading to enhanced susceptibility to atypical femoral fractures. These might include co-medication, previous underlying disease affecting bone integrity, proton-pump inhibitors and corticosteroids (Ing-Lorenzini et al. 2009, Rizzoli et al. 2011), possible negative pharmacodynamic interactions with other antiresorptive drugs such as estrogen, raloxifene, calcitonin, or denosumab (Visekruna et al. 2008, Shane et al. 2010), or the presence of an underlying disease affecting bone integrity such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, cancer, hypophosphatasia, or vitamin D deficiency.

Recently, Schilcher et al. (2011) published detailed information about co-medication in patients with an atypical fracture (e.g. hormone replacement therapy, corticosteroids, proton-pump inhibitors), and they observed no difference from patients with ordinary subtrochanteric fractures. In addition, there were no co-morbidities associated with atypical fractures. More specifically, some authors have searched for other potential risk factors in bisphosphonate-free patients with atypical femoral fractures, but so far without success (Tan et al. 2011).

This case report is the first to document that atypical femoral fractures can occur in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta, irrespective of whether or not this is related to treatment with bisphosphonates. Further investigation of a possible synergistic relationship between atypical fractures associated with bisphosphonate use and osteogenesis imperfecta may provide new information about the pathological mechanisms implicated in atypical femoral fractures.

Acknowledgments

RM: case study, research, and writing of the manuscript. KI, BU, RS, RP, and RR: supervision and review of the manuscript.

References

- Funds were recieved from University Hospitals of Geneva

- Adami S, Gatti D, Colapietro F, et al. Intravenous neridronate in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(1):126–30. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornemann M, Saxon JR, Kidd GS., 2nd Osteoporosis unmasked by hyperthyroidism in a young man with osteogenesis imperfecta. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147(11):1947–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMeglio LA, Peacock M. Two-year clinical trial of oral alendronate versus intravenous pamidronate in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(1):132–40. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durchschlag E, Paschalis EP, Zoehrer R, et al. Bone material properties in trabecular bone from human iliac crest biopsies after 3- and 5-year treatment with risedronate. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2006;21(10):1581–90. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti D, Antoniazzi F, Prizzi R, et al. Intravenous neridronate in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: a randomized controlled study. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(5):758–63. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ing-Lorenzini K, Desmeules J, Plachta O, et al. Low-energy femoral fractures associated with the long-term use of bisphosphonates: a case series from a Swiss university hospital. Drug Saf. 2009;32(9):775–85. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932090-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letocha AD, Cintas HL, Troendle JF, et al. Controlled trial of pamidronate in children with types III and IV osteogenesis imperfecta confirms vertebral gains but not short-term functional improvement. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(6):977–86. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashiba T, Turner CH, Hirano T, et al. Effects of suppressed bone turnover by bisphosphonates on microdamage accumulation and biomechanical properties in clinically relevant skeletal sites in beagles. Bone. 2001;28(5):524–31. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashiba T, Mori S, Burr DB, et al. The effects of suppressed bone remodeling by bisphosphonates on microdamage accumulation and degree of mineralization in the cortical bone of dog rib. J Bone Miner Metab. 2005;23((Suppl)):36–42. doi: 10.1007/BF03026321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier RP, Perneger TV, Stern R, et al. Increasing occurrence of atypical femoral fractures associated with bisphosphonate use. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(12):930–6. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels F. Die Bedeutung der Bauprinzipien des Stutz-und Bewegungsapparates fur die Beanspruchung der Röhrenknochen. Z Anat Entwicklungsgesch. 1948;114(1-2):129–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipi CA, Remmington T, Steiner RD. Bisphosphonate therapy for osteogenesis imperfecta. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD005088. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005088.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch F, Glorieux FH. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Lancet. 2004;363(9418):1377–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzoli R, Akesson K, Bouxsein M, et al. Subtrochanteric fractures after long-term treatment with bisphosphonates: a European Society on Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis, and International Osteoporosis Foundation Working Group Report. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(2):373–90. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1453-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakkers R, Kok D, Engelbert R, et al. Skeletal effects and functional outcome with olpadronate in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: a 2-year randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2004;363(9419):1427–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilcher J, Michaelsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(18):1728–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seikaly MG, Kopanati S, Salhab N, et al. Impact of alendronate on quality of life in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(6):786–91. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000176162.78980.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabat S. Osteogenesis imperfecta-induced migratory stress fractures in a military recruit. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18(5):654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shane E, Burr D, Ebeling PR, et al. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(11):2267–94. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spotila LD, Constantinou CD, Sereda L, et al. Mutation in a gene for type I procollagen (COL1A2) in a woman with postmenopausal osteoporosis: evidence for phenotypic and genotypic overlap with mild osteogenesis imperfecta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(12):5423–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan SC, Koh SB, Goh SK, et al. Atypical femoral stress fractures in bisphosphonate-free patients. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(7):2211–2. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1384-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visekruna M, Wilson D, McKiernan FE. Severely suppressed bone turnover and atypical skeletal fragility. J Clin Endocrinol Metsb. 2008;93(8):2948–52. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wekre LL, Froslie KF, Haugen L, et al. A population-based study of demographical variables and ability to perform activities of daily living in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(7):579–87. doi: 10.3109/09638280903204690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]