Abstract

Background. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) reflects an aberrant immune response that can develop in human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART). Its pathogenesis remains unclear.

Methods. We performed a nested case-control study using specimens from ACTG A5164. We compared plasma biomarkers and T-cell subsets in 19 IRIS and 39 control participants at study entry, ART initiation, and IRIS and used conditional logistic regression to develop IRIS predictive models. We evaluated the effect of corticosteroids on biomarker levels.

Results. Eleven and 8 participants developed paradoxical and unmasking IRIS, respectively, none while still receiving corticosteroids. Compared to controls, cases displayed elevations at study entry in interleukin (IL) 8, T-helper (Th) 1 (IL-2, interferon [IFN]-γ, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]) and Th17 (IL-17) cytokine levels that persisted through ART initiation and IRIS. In logistic regression, baseline higher IFN-γ and TNF were strong predictors of IRIS. Participants who received corticosteroids and later developed IRIS had marked increases in IL-6, IL-8, and IFN-γ at the time of IRIS. T-cell activation markers did not differ in cases and controls prior to ART but were increased in cases at the time of IRIS.

Conclusions. Increased IL-8, Th1, and Th17 cytokine levels in IRIS patients precede ART initiation and could help identify patient populations at higher risk for IRIS.

Potent combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) has dramatically reduced morbidity and mortality associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), but its use can be complicated by immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) [1]. Although no uniform definition exists, the diagnosis of IRIS requires the worsening of a recognized (“paradoxical” IRIS) or unrecognized (“unmasking” IRIS) preexisting infection in the setting of successful HIV suppression and improving immunologic function. IRIS has been reported in 3%–40% of patients initiating ART [2–6], with the wide range in reported incidence likely reflecting differences in case definitions and in the patient populations studied.

The immunopathogenesis of IRIS remains poorly understood, but the prevailing view is that IRIS reflects the atypical restoration of pathogen-specific immune response to microbial antigens [7]. Although there may be differences between paradoxical and unmasking IRIS and according to target antigen, some aspects of IRIS pathogenesis are likely shared among all IRIS events. For example, markers of antigen-presenting cell activation such as interleukin (IL) 6 have been found to be elevated prior to the development of IRIS to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, cryptococcus, and herpesviruses [8–10]. Although IRIS generally does not portend an unfavorable long-term prognosis, the development of IRIS may lead to hospitalization, the need for invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, or occasionally death [11]. Identifying biomarkers that predict the development of IRIS could lead to strategies to improve its diagnosis and reduce its incidence and associated morbidity and mortality.

Although corticosteroids are frequently used to treat severe IRIS [12], the effects of corticosteroids on cytokine levels and the development of IRIS have not been studied to date. In this study, we compared levels of biomarkers and T-cell subsets prior to and at the time of IRIS (or a matched time point) between participants who developed IRIS and controls as well as the effect of corticosteroids on these biomarkers during a randomized trial examining the optimal timing of ART during an acute opportunistic infection (OI).

METHODS

The AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) Study A5164 randomized 282 participants with nontuberculosis OIs or serious bacterial infections to early or deferred ART [13]. Participants were required to be randomized within 14 days of starting therapy for the OI that determined study eligibility. Participants in the early arm started ART within 48 hours of study entry (after a median of 11 days; [interquartile range {IQR}, 8–13] of treatment for their acute OI), whereas participants in the deferred arm initiated ART after a median of 45 days (IQR, 41–55 days) of treatment for their acute OI. The use of early ART led to a reduction in the composite endpoint of death or new OI without an increase in the rate of IRIS [13]. Plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were collected and stored at study entry, at ART initiation (in the deferred arm), at the time of IRIS diagnosis, at weeks 4, 8, 12, and 16, and subsequently every 8 weeks after ART initiation through study completion at week 48.

IRIS was predefined in the protocol as symptoms consistent with an infectious/inflammatory condition, temporally related to the initiation of ART, and associated with an increase in CD4+ T-cell count and/or a decrease in HIV RNA level, but not explained by a newly acquired infection, the expected clinical course of a previously diagnosed infection, or the side effects of ART. When IRIS was diagnosed by a site investigator, case records were adjudicated by an independent reviewer, blinded to study arm assignment.

We matched controls 2:1 to IRIS cases by entry OI, treatment arm, and the availability of stored samples. In one instance, a case was matched without consideration to treatment arm owing to limited stored samples in potential controls, and in another, a third control was selected to improve matching.

Using cryopreserved plasma, we assessed levels of IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-15, IL-17, interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and soluble TNF receptor II (sTNFrII) with a Bioplex system (Bio-Rad); β2-microglobulin and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; R&D and ALPCO, respectively); and D-dimer with enzyme-linked fluorescent assay (bioMérieux). Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed and evaluated by multiparameter flow cytometry and stained for CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25, CD27, CD38, CD45RO, CD57, CD127, HLA-DR, Ki67, FoxP3, CCR5, granzyme B, and LAG-3. Treg cells were defined as CD4+ T cells that were CD25 high, CD127 low, and FoxP3+. Samples were acquired on an LSR-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software. The laboratories performing the above immunologic assays (S. D. for Bioplex analysis; I. S. for high-sensitivity CRP, D-dimer, and white blood cell subset analysis) were blinded to which samples were from IRIS cases or controls. We performed the immunologic assays at study entry, at ART initiation (representing an additional time point in participants in the deferred arm), and at the time of IRIS (or a matched time point in control participants). Samples for the IRIS/matched time point for the IRIS cases and controls were collected 29 days (IQR, 24–42 days) and 28 days (IQR, 27–32 days) after ART initiation, respectively (P = .56).

In comparing plasma biomarker levels of cases and controls at different time points, we performed conditional logistic regression, adjusting for matching. Because of limited PBMC sample availability, we performed unmatched analyses using Wilcoxon rank sum tests to compare T-cell subset percentages between cases and controls. We also performed conditional logistic regression, adjusting for the matching, using log10 transformed plasma biomarker levels, to approximate normal distributions, at study entry to examine predictive biomarker models of IRIS. Because of the small number of IRIS cases, clinical markers were not explored in conjunction with the biomarkers.

Analysis of variance models were used in exploratory analyses to evaluate the association between corticosteroid receipt during the management of the acute OI, IRIS case/control status, and log10 transformed plasma biomarker levels. By adjusting for the development of IRIS and the interaction of IRIS and corticosteroids, we could determine if corticosteroids had a different effect on cytokine levels in individuals who were to develop IRIS vs those who would not. Additionally, we compared the change in plasma biomarker levels from study entry to the IRIS time point between participants who developed or did not develop IRIS and who received or did not receive corticosteroids using Kruskal–Wallis tests. Of note, corticosteroids were not assigned randomly during ACTG A5164, but were generally given in cases of severe Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP). For all the above analyses, we evaluated significance at P < .05 and did not correct for multiple comparisons.

ACTG A5164 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00055120) was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by all 46 of the participating sites’ institutional review boards, including the Stanford University Institutional Review Board, the lead site for the study. Written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to entry.

RESULTS

Of 282 participants enrolled in ACTG A5164, 262 initiated ART and had at least 1 subsequent study visit, thus allowing for the potential diagnosis of IRIS. Among the 262 participants, the median CD4+ T-cell count and plasma HIV RNA level at study entry were 30 cells/µL (IQR, 11–56 cells/µL) and 5.1 log10 copies/mL (IQR, 4.7–5.6 log10 copies/mL). Twenty (7.6%) participants developed IRIS. One identified IRIS case was excluded prior to the performance of immunologic assays, as, after additional review, it was unclear if the case truly represented IRIS. Plasma samples were available at baseline for all 19 cases and 39 controls and analyses were adjusted for matching. Baseline PBMC samples were available for 14 IRIS cases and 25 controls with analyses performed without adjusting for matching.

Clinical descriptions of and risk factors for IRIS during ACTG A5164 have been reported previously [14]. Thirteen of 19 IRIS cases had PCP as a presenting OI, 5 had cryptococcosis, and 2 each had Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infection or histoplasmosis. Six cases had >1 presenting OI. Five of the IRIS cases represented reactions to Cryptococcus (4 paradoxical and 1 unmasking), 5 to MAC (2 paradoxical and 3 unmasking), and 4 to P. jirovecii (all paradoxical).

The clinical characteristics of IRIS cases and controls did not differ (Table 1). Forty-two percent of IRIS cases (8/19) received corticosteroids during the management of their presenting OI and were receiving them at study entry, but all IRIS events developed after the course of corticosteroids had been completed. The median entry CD4+ T-cell count of IRIS cases was 18 cells/µL (IQR, 8–45 cells/µL) and the time from ART initiation to IRIS diagnosis was 34 days (IQR, 26–72 days).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics Among Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome Cases and HIV-Infected Controls

| Characteristic | IRIS Cases (n = 19) | HIV-Positive Controls (n = 39) | P Value for Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Age | 40 (35–45) | 37 (34–48) | .86 |

| Median Entry CD4+ T cells | 18 (8–45) | 14 (8–30) | .37 |

| Median Entry HIV RNA level | 5.0 (4.7–5.7) | 5.1 (4.5–5.5) | .42 |

| Presenting OI, % (no.) | |||

| Pneumocystis pneumonia | 68% (13) | 64% (25) | |

| Cryptococcosis | 26% (5) | 33% (13) | |

| MAC infection | 11% (2) | 5% (2) | |

| Histoplasmosis | 11% (2) | 3% (1) | |

| Other (cryptosporidiosis, tuberculosis, Kaposi sarcoma, bacterial infection) | 11% (2) | 8% (3) | |

| Early ART, % (no.) | 42% (8) | 44% (17) | b |

| Receiving corticosteroids during acute OI, % (no.) | 42% (8) | 56% (22) | .40 |

| Median days to IRIS after ART (IQR) | 34 (26–72) | NA | … |

| IRIS event, % (n) | |||

| Cryptococcus | 26% (5) | NA | … |

| MAC | 26% (5) | ||

| Pneumocystis jirovecii | 21% (4) | ||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosisa | 5% (1) | ||

| Histoplasma | 5% (1) | ||

| Cytomegalovirus | 5% (1) | ||

| Varicella zoster virus | 5% (1) | ||

| Hepatitis C virus (11 paradoxical, 8 unmasking) | 5% (1) |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; MAC, Mycobacterium avium complex; NA, not applicable; OI, opportunistic infection.

a Patients diagnosed with tuberculosis postrandomization were allowed to remain on-study.

b P values not presented for these variables, as cases and controls were matched on variable.

There were distinct differences in plasma biomarker levels that distinguished IRIS cases from controls. Cases demonstrated a heightened T-helper (Th) 1 (IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF) and Th17 (IL-17) cytokine response that was evident at study entry and remained present at ART initiation (which represented the same time point in individuals in the early arm) and at the time of IRIS, although not all comparisons of these cytokine levels at all time points reached statistical significance (Table 2). Additionally, cases had significantly higher IL-8 levels at study entry and at ART initiation than did controls. IL-8 tended to remain higher in cases than in controls at the time of IRIS, but the difference no longer reached the level of statistical significance. Levels of nonspecific markers of inflammation such as IL-6 and CRP did not show statistically significant differences at any time points between cases and controls, while β2-microglobulin levels were higher in cases than in controls at study entry and at ART initiation.

Table 2.

Plasma Biomarker Levels in Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome Cases vs Controls

| Plasma Biomarker | Study Entry |

ART Start |

IRIS Time Point |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRIS Cases (n = 19) | Controls (n = 39) | IRIS Cases (n = 19) | Controls (n = 39) | IRIS Cases (n = 18) | Controls (n = 37) | |

| IL-1, pg/mL | 1.2 (0.7, 3.4) | 1.2 (0.6, 3.0) | 1.3* (0.9, 11.7) | 1.0* (0.5, 1.4) | 1.8 (0.6, 5.3) | 1.1 (0.6, 1.4) |

| IL-2, pg/mL | 2.2* (0.8, 8.5) | 1.2* (0.6, 2.8) | 2.7* (0.8, 8.5) | 1.2* (0.6, 2.6) | 5.3 (0.8, 37.1) | 1.3 (0.5, 4.9) |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 15.0 (7.4, 87.8) | 20.1 (3.0, 64.1) | 31.7 (10.2, 91.4) | 10.5 (2.4, 43.7) | 40.5 (10.0, 91.9) | 19.2 (3.3, 42.2) |

| IL-8, pg/mL | 24.1* (8.6, 29.6) | 10.9* (5.1, 19.3) | 22.3* (11.5, 34.6) | 9.7* (5.0, 20.5) | 25.8 (6.4, 36.7) | 9.1 (4.3, 17.1) |

| IL-10, pg/mL | 20.8 (10.6, 46.6) | 18.7 (8.5, 31.6) | 13.1 (8.4, 45.3) | 19.7 (7.9, 31.6) | 9.0 (5.0, 158) | 7.9 (5.2, 16.9) |

| IL-15, pg/mL | 5.1 (2.8, 12.2) | 3.8 (1.8, 7.2) | 5.1* (2.4, 13.0) | 3.0* (1.5, 7.4) | 2.6 (1.6, 5.5) | 1.7 (1.0, 3.7) |

| IL-17, pg/mL | 6.0* (2.4, 18.8) | 2.1* (1.2, 5.1) | 6.0* (2.4, 18.8) | 2.1* (1.2, 5.1) | 7.8* (2.9, 31.6) | 2.4* (0.6, 6.7) |

| IFN-γ, pg/mL | 35.2** (9.5, 97.0) | 5.8** (2.2, 22.1) | 31.5** (6.7, 97.0) | 9.2** (2.9, 20.4) | 39.2* (13.9, 116) | 12.8* (4.8, 40.7) |

| TNF, pg/mL | 22.2** (11.5, 36.5) | 11.2** (4.7, 18.9) | 21.1* (11.5, 45.1) | 12.3* (4.7, 20.7) | 17.6 (8.2, 48.0) | 9.0 (6.4, 19.8) |

| sTNFrII, pg/mL | 4.1 (2.9, 4.8) | 2.7 (1.9, 3.2) | 3.4 (2.2, 4.1) | 2.7 (1.8, 3.6) | 2.9* (2.0, 4.3) | 2.1* (1.4, 3.1) |

| CRP, mg/L | 13.2 (3.4, 21.4) | 16.6 (5.8, 38.1) | 10.4 (2.8, 19.0) | 12.9 (1.5, 29.3) | 26.0 (3.6, 61.5) | 7.0 (2.6, 30.1) |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 1.8 (1.5, 2.9) | 1.4a (0.7, 2.2) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.1) | 0.9a (0.6, 2.0) | 1.1 (0.6, 2.3) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.7) |

| β2-microglobulin, µg/dL | 4.9* (3.4, 11.3) | 4.1* (3.1, 4.9) | 5.2* (4.3, 11.3) | 4.8* (3.2, 6.2) | 4.3 (3.3, 8.3) | 4.0 (3.0, 6.3) |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range). P values were calculated using conditional logistic regression.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CRP, C-reactive protein; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; sTNFrII, soluble TNF receptor II ; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

a One subject did not have available sample for testing at this time point.

* P < .05.

** P < .01 for IRIS cases vs controls at a given time point.

We also compared biomarker levels in paradoxical (and unmasking) IRIS cases to their respective controls to determine if there were biomarker profiles that were distinct between paradoxical and unmasking IRIS. No new patterns emerged with, in general, higher levels of IL-8 and Th1 and Th17 cytokines common to both types of IRIS cases compared to controls. However, fewer comparisons reached statistical significance given the smaller numbers in each comparison group (data not shown).

For the entire study population, in logistic regression, higher IFN-γ at study entry was a strong predictor of the development of IRIS (odds ratio [OR], 5.6 per each 1 log10 higher at study entry; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.8–17.2; P = .003). An additional single predictor of the development of IRIS was higher TNF at study entry (OR, 12.3 per each l log10 higher at study entry; 95% CI, 1.8–81.6; P = .01). However, a predictive model that incorporated multiple plasma biomarkers could not be developed, owing to the small sample size and high degree of correlation among plasma biomarkers levels.

After controlling for the receipt of corticosteroids during management of the acute OI, the association between the development of IRIS and elevated levels of Th1 (IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF) and Th17 cytokines was maintained (Table 3). At study entry and ART initiation, we found TNF, sTNFrII, and IL-8 levels to be lower in participants who received corticosteroids than in participants who did not receive corticosteroids after controlling for IRIS case/control status (P < .05 for all comparisons).

Table 3.

Association of Corticosteroid Administration During Acute Opportunistic Infection and Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome on Plasma Biomarker Levelsa

| Plasma Marker | Study Entry |

ART Start |

IRIS Time Point |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRIS (n = 19) vs Controls (n = 39) | CS (n = 30) vs No CS (n = 28) | IRIS (n = 19) vs Controls (n = 39) | CS (n = 30) vs No CS (n = 28) | IRIS (n = 18) vs Controls (n = 37) | CS (n = 29) vs No CS (n = 26) | |

| IL-1 | … | … | ↑** | … | … | … |

| IL-2 | ↑* | … | ↑* | … | ↑* | … |

| IL-6 | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| IL-8 | … | ↓* | … | ↓* | § | § |

| IL-10 | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| IL-15 | … | … | ↑* | … | … | … |

| IL-17 | ↑* | … | ↑* | … | ↑** | … |

| IFN-γ | ↑** | … | ↑** | … | ↑* | … |

| TNF | ↑* | ↓** | ↑* | ↓* | … | … |

| sTNFrII | … | ↓** | … | ↓** | … | … |

| CRP | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| D-dimer | … | ↓** | § | § | § | § |

| β2-microglobulin | § | § | … | ↓** | … | … |

Abbreviations: –, no significant association; ART, antiretroviral therapy; CRP, C-reactive protein; CS, corticosteroid; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; sTNFrII, ; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

a Based on analysis of variance models, evaluating the independent association between the development of IRIS, corticosteroid receipt during the management of the acute opportunistic infection and the levels of plasma markers (log10 transformed to approximate normal distributions). At each time point, the model adjusts for both IRIS case/control status and receipt of corticosteroids. If the interaction term was statistically significant, the model adjusts for IRIS case/control status, receipt of corticosteroids, and the interaction term; ↑ (↓) Indicates significant positive (or negative) association between IRIS or corticosteroid receipt and plasma biomarker level.

* Indicates association at P < .05 level.

** Indicates association at P < .01 level.

§ Indicates significant interaction of IRIS and corticosteroid receipt with plasma marker level.

There were significant differences in change in IL-6, IL-8, IFN-γ, TNF, sTNFrII, and β2-microglobulin from study entry to the time of IRIS among the 4 groups defined by early receipt of corticosteroids and eventual development of IRIS (Table 4). The patterns differed with marked increases in IL-6, IL-8, IFN-γ, and β2-microglobulin in those who had received corticosteroids and later developed IRIS, and sizable decreases in IL-6, IFN-γ, TNF, and sTNFrII among participants who developed IRIS and never received corticosteroids.

Table 4.

Change From Study Entry to Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome (IRIS) Time Point in Selected Plasma Biomarker Levels Among Participants Receiving or Not Receiving Corticosteroids by IRIS Category

| IRIS |

Controls |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma Biomarker | After Receiving CS (n = 8) | No CS (n = 10) | After Receiving CS (n = 21) | No CS (n = 16) | P Valuea |

| IL-2, pg/mL | 4.5 (−0.2, 7.5) | 0 (−1.4, 31.7) | 0.2 (−0.1, 2.3) | −0.4 (−1.0, 0.6) | .320 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 45.4 (3.0 , 945) | −16.5 (−53.4, −3.9) | 0.5 (−5.3, 25.6) | 0.8 (−12.7, 21.2) | .021 |

| IL-8, pg/mL | 10.6 (4.1, 68.8) | −1.9 (−7.4, 0.3) | 1.9 (−2.6, 3.7) | 0.7 (−9.1, 7.2) | .024 |

| IL-17, pg/mL | 2.1 (−0.4, 164) | −1.9 (−8.2, 0.3) | 0 (−1.7, 2.2) | −0.4 (−2.1, 1.1) | .234 |

| IFN-γ, pg/mL | 14.4 (6.1, 121.5) | −24.6 (−124, 1.7) | 5.5 (−0.30, 22.4) | 0.5 (−16.0, 8.5) | .014 |

| TNF, pg/mL | 0.0 (−1.1, 22.0) | −7.2 (−17.0, −4.9) | 0.2 (−2.4, 7.5) | −2.9 (−6.6, 7.5) | .018 |

| sTNFrII, pg/mL | 0.2 (−0.3, 1.1) | −1.5 (−2.6, −1.0) | −0.4 (−0.9, 0.6) | −0.8 (−1.3, 0.0) | .004 |

| CRP, mg/L | 1.0 (−13.7, 24.9) | 3.4 (−6.3, 58.1) | −1.0 (−5.6, 8.5) | −5.42 (−31.8, 8.2) | .36 |

| β2-microglobulin, µg/dL | 1.3 (−0.4, 3.2) | −1.5 (−4.6, −0.9) | 0.1 (−1.0, 2.2) | −0.5 (−1.2, 0.8) | .013 |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range).

Abbreviations: CRP, C-reactive protein; CS, corticosteroid; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; sTNFrII, ; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

a P values were calculated using Kruskal–Wallis test, comparing the distribution of the plasma biomarkers across the 4 groups.

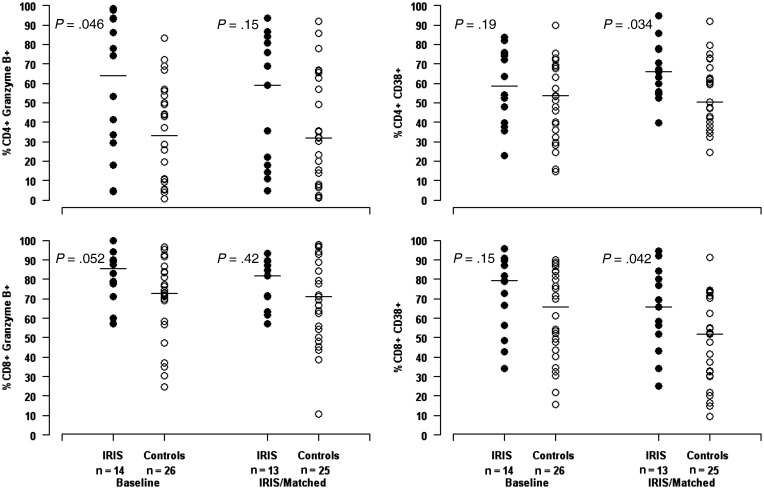

In general, there were few differences in T-cell subset percentages between IRIS cases and controls (Figure 1). IRIS cases displayed higher percentages of CD4+ granzyme B+ T cells than controls did at study entry (63.9% vs 33.0%, P = .046). Additionally, markers of immune activation were increased in cases compared to controls at the time of IRIS. Cases had increased percentages of CD4+CD38+ and CD8+CD38+ T cells compared with controls (P = .034 and P = .042, respectively). IRIS cases also tended to have increased percentages of CD38+/HLA-DR+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells compared with controls at the time of IRIS, but these differences did not reach statistical significance (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Comparison of T-cell activation status in immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) and control participants at baseline and IRIS time point. P values comparing T-cell subset percentages between IRIS cases and controls were calculated using Wilcoxon tests. Multiple additional comparisons in T-cell subsets were performed (all nonsignificant) including proportions of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing Ki67, CD25+, CD127+, HLA–DR+, CCR5+, CD57+, PD1+, and LAG3+.

DISCUSSION

In this nested case-control study evaluating the predictors and determinants of IRIS in a patient population with advanced HIV disease who presented with a diverse set of acute OIs, we found an immunologic profile that identified a subset of patients who were at increased risk for the development of IRIS. Increased levels of IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF, IL-17, and IL-8 at study entry were associated with the development of IRIS. The levels of these markers were elevated at study entry and at ART initiation and remained elevated at the time of IRIS. Of the markers, elevated IFN-γ or TNF at study entry were strong predictors of the development of IRIS.

Consistent with our findings of increased levels of IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF, a Th1 bias and proinflammatory component prior to ART initiation has been previously reported in studies of paradoxical and unmasking tuberculosis IRIS [10, 15–17]. Th1 cytokines activate macrophages and help in the eradication of intracellular microorganisms such as mycobacteria. Our findings also are supported by a mouse model of mycobacterial IRIS, where IFN-γ played a crucial role in the development of IRIS [18]. Earlier studies, however, found that higher baseline plasma levels of Th2 cytokines and lower levels of Th1 cytokines in the cerebrospinal fluid were predictive of the development of paradoxical cryptococcal IRIS [9, 19]. With only 4 participants with paradoxical cryptococcal IRIS, we did not have the power within our study to determine the cytokine profile of participants with this particular condition.

Previous studies have suggested that elevated baseline CRP and IL-6 levels can predict the development of IRIS [8, 15, 20]. A number of explanations could account for the lack of association between levels of these biomarkers and IRIS in our study. We may have been underpowered to find an effect. IL-6 was increased in IRIS cases compared to controls at both ART initiation and the IRIS time point, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. Additionally, others have reported that ELISA assays may be superior to multiplex bead assays when evaluating the significance of IL-6 levels [21]. The majority of patients in previous studies reporting a relationship between IL-6 and CRP and IRIS developed unmasking IRIS, and the presence of elevated levels of these markers may reflect the presence of an undiagnosed OI. In this study, baseline elevated IL-6 and CRP levels did not identify patients at higher risk for the development of IRIS, perhaps because all participants had an active OI at baseline.

Corticosteroids have been shown to reduce plasma levels of IL-6 and CRP [22], and the high percentage of participants in our study who received corticosteroids (30/58) could have also contributed to the lack of baseline differences in these biomarkers between cases and controls. Baseline IL-6 levels appeared blunted by corticosteroids in our IRIS participants, as participants who received corticosteroids and would later develop IRIS had a marked increase in IL-6 after the discontinuation of corticosteroids. We did not, however, observe this same effect with corticosteroids on CRP. IL-6 and CRP levels often correlate, as IL-6 induces hepatic production of CRP, but this may be attenuated in the presence of IFN-α [23], a cytokine recognized to be upregulated in chronic HIV infection [24].

In normal immune homeostasis, proinflammatory Th17 responses (ie, IL-17) are counterbalanced by regulatory T-cell activity [25]. Others have also found an association between increased IL-17 levels and the development of IRIS [9]. Increased Th17 responses have also been implicated in other diseases associated with immune dysregulation and inflammation such as rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, lupus, and allograft rejection [26]. Here, although IL-17 levels in plasma were increased in those who developed IRIS, there was no associated decrease in the proportions of circulating CD4+ T cells with a T-regulatory phenotype. Some have proposed that the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 may play a role in the pathogenesis of IRIS [27] and have suggested that elevated IL-10 levels can lead to reversible T-cell dysfunction [28], but our data did not suggest a role for IL-10 in IRIS.

IL-8 is a chemokine produced by macrophages and epithelial cells with a primary function of inducing neutrophil chemotaxis. We found higher IL-8 levels at study entry in those participants who developed IRIS, reflecting the potential role of the innate immune system in the pathogenesis of IRIS [29, 30]. Boulware and colleagues found higher IL-8 levels 1 month post-ART initiation in those who developed IRIS compared to those who did not [31]. However, a lower CSF IL-8 level has been associated with the development of paradoxical cryptococcal IRIS [19], perhaps reinforcing the compartmentalization of immune responses during IRIS.

We saw few differences in percentages of T-cell subsets between IRIS cases and controls. Consistent with previous publications, we found IRIS participants to have generally higher percentages of activated T-cells at the time of IRIS [16, 32] but not prior to ART. This could be due to the clinical acuity of our entire cohort and may also suggest that systemic T-cell activation is not a proximate cause but rather a consequence of IRIS pathogenesis.

It is unclear which cells are primarily responsible for the excess cytokine levels found in IRIS cases in our study, but our data suggest that both increased T-cell and innate immune responses may be present. While IL-2 and IL-17 are predominantly produced by T cells, TNF and IL-8 are both likely of monocyte/macrophage origin. Antigen-reactive T cells may be the most likely source of the elevated IFN-γ, but IFN-γ could have also been produced by natural killer (NK) cells, consistent with recent data from the CAMELIA study, which showed that the NK-cell degranulation potential was higher in patients who developed tuberculosis IRIS [30].

Corticosteroids are frequently used to treat severe cases of IRIS. In a randomized study in paradoxical tuberculosis IRIS, prednisone led to a reduction in hospitalization and an improvement in quality of life without an increase in serious infections [12]. Using stored samples from the aforementioned study, Meintjes and colleagues reported that corticosteroids led to significant declines in proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6, TNF, and IFN-γ but no change in tuberculosis-specific T-cell responses [33].

Corticosteroids have never been studied as preventive therapy for IRIS. Corticosteroids are known to diffuse passively across the cellular membrane and bind to intracellular glucocorticoid receptors, leading to downstream inhibition of cytokine production primarily through the blocking of transcriptional factors [34]. In our exploratory analysis, after controlling for the development of IRIS, we found that participants who received corticosteroids had lower levels of TNF, sTNFrII, and IL-8 at baseline than participants who were not receiving corticosteroids. Elevated levels of these proinflammatory markers were associated with the later development of IRIS. Additionally, we saw increases in the proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, IL-6, and IL-8 in those who had received corticosteroids and later developed IRIS. Since corticosteroids inhibit the production of many of the cytokines associated with the development of IRIS, our data suggest that corticosteroids could play a role in potentially delaying or even reducing the occurrence of IRIS.

There are a number of limitations of this study. Our findings may only apply to the development of IRIS in those individuals presenting with an acute nontuberculosis OI, and it may not be appropriate to extrapolate these results to the prediction of IRIS in patients initiating ART who have tuberculosis or who are asymptomatic. Also, owing to the relatively few participants, we may have been underpowered to detect some important immunologic differences between cases and controls and between paradoxical and unmasking IRIS. While the matching strategy led to cases and controls having similar clinical characteristics, the lack of sample availability for PBMCs required many analyses to be performed in an unmatched fashion. Additionally, by including a heterogeneous sample of IRIS cases, immunologic pathways that could underlie the pathogenesis of IRIS to specific pathogens may not have been elucidated. Corticosteroids were not assigned randomly within ACTG A5164 and generally were given to participants with severe PCP. Immunologic differences detected between participants who received corticosteroids and those who did not might only reflect differences in the clinical characteristics between these patient groups. We chose to report differences between cases and controls at both study entry and ART start, recognizing that findings at these time points were not independent of each other, given that for participants in the early ART arm, these represented the same time point.

In summary, among participants who present with an opportunistic infection, those with a baseline proinflammatory cytokine environment characterized by elevated levels of Th1 cytokines, IL-8, and IL-17 appear to be at increased risk for the development of IRIS. While altered T-cell function may underlie IRIS, unique T-cell subset abnormalities that preceded the development of IRIS were not apparent in our study. It also appears that corticosteroids do suppress the same inflammatory markers that seem to identify patients at higher risk for IRIS, lending some support for their empirical use for treatment and potential prevention of IRIS events.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported in part by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI38858, AI68636, and AI6863). I. S. was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Race EM, Adelson-Mitty J, Kriegel GR, et al. Focal mycobacterial lymphadenitis following initiation of protease-inhibitor therapy in patients with advanced HIV-1 disease. Lancet. 1998;351:252–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04352-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breton G, Duval X, Estellat C, et al. Determinants of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV type-1 infected patients with tuberculosis after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1709–12. doi: 10.1086/425742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shelburne SA, Visnegarwala F, Darcourt J, et al. Incidence and risk factors for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome during highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2005;19:399–406. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000161769.06158.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratnam I, Chiu C, Kandala NB, Easterbrook PJ. Incidence and risk factors for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in an ethnically diverse HIV type 1-infected cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:418–27. doi: 10.1086/499356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murdoch DM, Venter W, Feldman C, Van Rie A. Incidence and risk factors for the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV patients in South Africa: a prospective study. AIDS. 2008;22:601–10. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f4a607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischl M, Mollan K, Pahwa S, et al. IRIS among US subjects starting ART in AIDS Clinical Trials Group study A5202 [abstract 791] Program and abstracts of the 17th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. 16–19 February 2010. San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foudraine N, Hovenkamp E, Notermans DW, et al. Immunopathology as a result of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS. 1999;13:177–84. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199902040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stone SF, Price P, Brochier J, French MA. Plasma bioavailable interleukin-6 is elevated in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients who experience herpesvirus-associated immune restoration disease after start of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1073–7. doi: 10.1086/323599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulware DR, Meya DB, Bergemann TL, et al. Clinical features and serum biomarkers in HIV immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome after cryptococcal meningitis: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourgarit A, Carcelain G, Martinez V, et al. Explosion of tuberculin-specific Th1-responses induces immune restoration syndrome in tuberculosis and HIV co-infected patients. AIDS. 2006;20:F1–7. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000202648.18526.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park WB, Choe PG, Jo JH, Kim SH, Bang JH, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in the first year after HAART: influence on long-term clinical outcome. AIDS. 2006;20:2390–2. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328010f201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meintjes G, Wilkinson RJ, Morroni C, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of prednisone for paradoxical tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. AIDS. 2010;24:2381–90. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833dfc68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zolopa AR, Andersen J, Komarow L, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy reduces AIDS progression/death in individuals with acute opportunistic infections: A multicenter randomized strategy trial. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant P, Komarow L, Andersen J, et al. Risk factor analyses for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) during a randomized study of early vs. deferred ART during an acute opportunistic infection (ACTG A5164) PLoS One. 2010;5:e11416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haddow LJ, Dibben O, Moosa MY, et al. Circulating inflammatory biomarkers can predict and characterize tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. AIDS. 2011;25:1163–74. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283477d67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antonelli LR, Mahnke Y, Hodge JN, et al. Elevated frequencies of highly activated CD4+ T cells in HIV+ patients developing immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Blood. 2010;116:3818–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-285080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elliott JH, Vohith K, Saramony S, et al. Immunopathogenesis and diagnosis of tuberculosis and tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome during early antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1736–45. doi: 10.1086/644784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barber DL, Mayer-Barber KD, Antonelli LR, et al. Th1-driven immune reconstitution disease in Mycobacterium avium-infected mice. Blood. 2010;116:3485–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-286336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boulware DR, Bonham SC, Meya DB, et al. Paucity of initial cerebrospinal fluid inflammation in cryptococcal meningitis is associated with subsequent immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:962–70. doi: 10.1086/655785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porter BO, Ouedraogo GL, Hodge JN, et al. d-Dimer and CRP levels are elevated prior to antiretroviral treatment in patients who develop IRIS. Clin Immunol. 2010;136:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cozzi-Lepri A, French MA, Baxter J, et al. Resumption of HIV replication is associated with monocyte/macrophage derived cytokine and chemokine changes: results from a large international clinical trial. AIDS. 2011;25:1207–17. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283471f10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okada Y, Shinohara M, Kobayashi T, et al. Effect of corticosteroids in addition to intravenous gamma globulin therapy on serum cytokine levels in the acute phase of Kawasaki disease in children. J Pediatr. 2003;143:363–7. doi: 10.1067/s0022-3476(03)00387-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Enocsson H, Sjowall C, Skogh T, Eloranta ML, Ronnblom L, Wettero J. Interferon-alpha mediates suppression of C-reactive protein: explanation for muted C-reactive protein response in lupus flares? Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3755–60. doi: 10.1002/art.25042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sedaghat AR, German J, Teslovich TM, et al. Chronic CD4+ T-cell activation and depletion in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: type I interferon-mediated disruption of T-cell dynamics. J Virol. 2008;82:1870–83. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02228-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinman L. A brief history of T(H)17, the first major revision in the T(H)1/T(H)2 hypothesis of T cell-mediated tissue damage. Nat Med. 2007;13:139–45. doi: 10.1038/nm1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sereti I, Rodger AJ, French MA. Biomarkers in immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: signals from pathogenesis. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5:504–10. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833ed774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Said EA, Dupuy FP, Trautmann L, et al. Programmed death-1-induced interleukin-10 production by monocytes impairs CD4þ T cell activation during HIV infection. Nat Med. 2010;16:452–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliver BG, Elliott JH, Price P, et al. Mediators of innate and adaptive immune responses differentially affect immune restoration disease associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis in HIV patients beginning antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1728–37. doi: 10.1086/657082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pean P, Nerrienet E, Madec Y, et al. Natural killer cell degranulation capacity predicts early onset of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) in HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis. Blood. 2012;119:3315–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boulware DR, Hullsiek KH, Puronen CE, et al. Higher levels of CRP, D-dimer, IL-6, and hyaluronic acid before initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) are associated with increased risk of AIDS or death. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1637–46. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan DB, Yong YK, Tan HY, et al. Immunological profiles of immune restoration disease presenting as mycobacterial lymphadenitis and cryptococcal meningitis. HIV Med. 2008;9:307–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meintjes G, Skolimowska KH, Wilkinson KA, et al. Corticosteroid modulated immune activation in the TB immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:369–77. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0094OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheinman RI, Cogswell PC, Lofquist AK, Baldwin AS., Jr Role of transcriptional activation of I kappa B alpha in mediation of immunosuppression by glucocorticoids. Science. 1995;270:283–6. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]