Abstract

We previously reported that overexpression of the rice homeobox gene OSH1 led to altered morphology and hormone levels in transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) plants. Among the hormones whose levels were changed, GA1 was dramatically reduced. Here we report the results of our analysis on the regulatory mechanism(s) of OSH1 on GA metabolism. GA53 and GA20, precursors of GA1, were applied separately to transgenic tobacco plants exhibiting severely changed morphology due to overexpression of OSH1. Only treatment with the end product of GA 20-oxidase, GA20, resulted in a striking promotion of stem elongation in transgenic tobacco plants. The internal GA1 and GA20 contents in OSH1-transformed tobacco were dramatically reduced compared with those of wild-type plants, whereas the level of GA19, a mid-product of GA 20-oxidase, was 25% of the wild-type level. We have isolated a cDNA encoding a putative tobacco GA 20-oxidase, which is mainly expressed in vegetative stem tissue. RNA-blot analysis revealed that GA 20-oxidase gene expression was suppressed in stem tissue of OSH1-transformed tobacco plants. Based on these results, we conclude that overexpression of OSH1 causes a reduction of the level of GA1 by suppressing GA 20-oxidase expression.

The regulatory mechanisms controlling plant morphogenesis constitute one of the most important questions in plant biology. The homeobox gene knotted-1, which is involved in maize leaf development, was isolated in 1989 (Hake et al., 1989). Many plant homeobox genes have subsequently been isolated and it is believed that these genes play a role in regulating morphogenesis (Kerstetter et al., 1994). The homeobox gene products share a unique and homologous structure, the homeodomain (Gehring, 1987). Homeodomain proteins possess a helix-turn-helix motif, and recognize and bind to specific DNA sequences, resulting in altered expression of the target gene (Scott et al., 1989). Accordingly, plant homeobox genes are thought to control plant morphogenesis through the regulation of expression of genes involved in plant development.

It has been reported that ectopic expression of the rice homeobox gene OSH1 causes morphological changes in rice, Arabidopsis, tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.), and kiwifruit (Kano-Murakami et al., 1993; Matsuoka et al., 1993; Kusaba et al., 1995). For example, OSH1-transformed tobacco plants exhibit abnormal-shaped leaves and flowers, and loss of apical dominance. These observations suggest that the OSH1 gene product may regulate the expression of genes involved in plant morphogenesis. Kano-Murakami et al. (1993) suggested that OSH1 need not be expressed continuously or throughout the entire plant to result in morphological aberrations. These results indicate that OSH1 may be a morphological regulator acting at an early stage of tissue or organ differentiation. However, the molecular mechanism(s) by which OSH1 regulates plant morphogenesis are unknown.

Plant morphogenesis is thought to be regulated by various physiological factors, including gene expression and plant hormones. It is well known that different plant hormones have distinct influences on plant growth and development. Our recent results indicate that ectopic expression of OSH1 causes morphological changes in transgenic tobacco plants by affecting plant hormone metabolism (Kusaba et al., 1998). In OSH1-transformed tobacco plants showing dwarfism, GA1 levels were drastically reduced. From the fact that ectopic expression of OSH1 causes morphological changes and the product of OSH1 contains a putative DNA-binding domain, it is possible that OSH1 regulates the expression of gene(s) involved in hormone metabolism or sensitivity of plants. In the present study we report results that implicate OSH1 in the regulation of expression of a gene involved in GA biosynthesis in transgenic tobacco plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

The preparation of OSH1-transformed tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum cv Samsun NN) plants was as described in Kano-Murakami et al. (1993). T2 seedlings of 35S-OSH1 transformants and wild-type seedlings were grown under greenhouse conditions at 25°C.

Treatment with GA Derivatives

Ten microliters of a 10 or 100 μm solution of GA20 or GA53 in 5% acetone was applied to the shoot apex of severe-phenotype transformants once a week. GA20 and GA53 used in this study were prepared as described in a previous report (Murofushi et al., 1982).

Analysis of GA Derivatives

Analysis of GA1, GA20, and GA19 was performed by ELISA using antibodies raised against GA4 (Nakajima et al., 1991), GA20 methyl-ester (Yamaguchi et al., 1987), and GA24 (Yamaguchi et al., 1992), respectively. Extraction of GA derivatives and ELISA procedures were performed as described in Kusaba et al. (1998) with some modifications to the HPLC conditions. HPLC analyses of extracts were performed using an ODS column (6- × 150-mm i.d.; Pegasil ODS, Senshu Kagaku, Tokyo, Japan). Samples were eluted with 0.5% acetic acid in 10% aqueous acetonitrile (solvent A) and 0.5% acetic acid in 80% aqueous acetonitrile (solvent B) at room temperature as follows: 0 to 30 min, linear gradient of 0% solvent B to 50% solvent B; 30 to 35 min, linear gradient of 50% solvent B to 100% solvent B; and 35 to 50 min, isocratic elution with solvent B. The flow rate of the solvent was 1.5 mL min−1 and fractions were collected every minute. The retention times of GA1, GA19, and GA20 were 20 to 21 min, 20 to 22 min, and 21 to 23 min, respectively. Fractions containing each GA (retention time ±3 min) were divided into three parts and assayed by ELISA. The cross-reactivity of the antibodies to other GAs was less than 1%.

Cloning of Tobacco GA 20-Oxidase PCR Fragment

First-strand cDNA was synthesized using a reverse transcription-PCR Kit (Takara Shuzo, Otsu, Shiga, Japan) with random primers. Total RNA extracted from young leaves of wild-type tobacco was used as a template. PCR was carried out with primers (5′-CA[AG]TT[CT]AT[ACT]TGGCCNGA-3′ and 5′-CTGACGGAGCGCCATTCGTTG-3′) using the first-strand cDNA as a template. Samples were heated to 94°C for 2 min, then subjected to 28 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s. The reaction was completed by a 10-min incubation at 72°C. The resulting 720-bp DNA fragment was cloned into the vector pCRII (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA).

Isolation of cDNA Clones

A cDNA library was constructed from RNA isolated from stem tissue of mature tobacco plants. Poly(A+)-enriched RNA was purified by two passes through an oligo d(T) cellulose column (Type 7, Pharmacia Biotech). Double-stranded cDNA was synthesized from poly(A+) RNA and EcoRI adapters were added using a cDNA synthesis kit (Pharmacia Biotech). The products were ligated into λZAP II (Stratagene) that had been digested with EcoRI and dephosphorylated. Ligation products were packaged using Gigapack II (Stratagene) and the resulting cDNA library of 2.4 × 105 recombinants was amplified by passage through Escherichia coli XL1 Blue. Screening was performed in 6× SSC, 5× Denhardt's solution, 0.1% SDS, and 100 μg mL−1 salmon-sperm DNA at 57°C for 16 h using the PCR product described above as a probe. Filters were washed in 2× SSC and 0.1% SDS at room temperature and then further washed in 0.2× SSC and 0.2% SDS at 57°C.

Sequence Analysis

Nucleotide sequences were determined by the dideoxynucleotide chain-termination method using an automated sequencing system (ALF DNA Sequencer II, Pharmacia Biotech). Analysis of cDNA and inferred amino acid sequences were carried out using Lasergene computer software (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, WI).

RNA-Blot Analysis

Total RNA was prepared from various organs for gel-blot analysis. Ten micrograms of each RNA preparation was separated on agarose gels in the presence of formaldehyde, followed by transfer to Hybond-N membrane (Amersham). The tobacco GA 20-oxidase cDNA or a XbaI/SacI fragment of the OSH1 cDNA was labeled with [α-32P]dCTP using the Rediprime DNA-labeling system (Amersham). Hybridization was carried out at 42°C in a solution containing 50% formamide, 5× SSC, 0.2% SDS, 0.1% N-lauroylsarcosine, 1% blocking reagent (Boehringer Mannheim), 10% dextran sulfate, and 100 μg mL−1 salmon- sperm DNA. Blots were hybridized for 14 h, washed in 2× SSC and 0.1% SDS at room temperature, then in 0.2× SSC and 0.1% SDS at 65°C, and then exposed to Kodak XAR film.

RESULTS

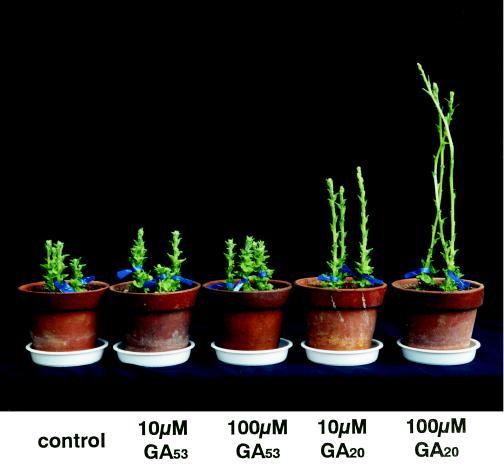

We previously demonstrated that the morphology of transgenic tobacco plants expressing OSH1 under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter could be divided into three categories ranging from a mild to a severe phenotype (Kano-Murakami et al., 1993). In these transformants severe-phenotype plants were dwarf and the axillary buds developed into vegetative stems; these buds were dormant in wild-type plants (Fig. 1). We have analyzed the hormone contents of OSH1-transformed tobacco plants to investigate the regulatory mechanism(s) through which OSH1 alters plant morphogenesis, and have shown that the morphological changes are accompanied by a decrease of GA1 content (Kusaba et al., 1998).

Figure 1.

Severe-phenotype transgenic tobacco plants expressing OSH1.

Treatment of Severe-Phenotype Tobacco Plants with GA1 Precursors

We have previously reported that stem elongation in severe-phenotype OSH1-transformed tobacco plants was restored by GA3 treatment (Kusaba et al., 1998). This suggests that the dwarfism observed in plants expressing OSH1 at a high level could be caused by the suppression of GA1 biosynthesis by OSH1 rather than changes in the GA1 signal transduction pathway. If this is the case, precursors of GA1 that are formed after the OSH1 block point in the GA biosynthetic pathway should be able to restore stem elongation in severe-phenotype plants. When GA53, a substrate of GA 20-oxidase, and GA20, an end product of GA 20-oxidase, were applied to the shoot apex of severe-phenotype transgenic tobacco plants, only GA20 could restore stem elongatation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2). This result indicates that in OSH1-overexpressing plants the GA biosynthetic pathway is blocked between GA53 and GA20.

Figure 2.

Stem elongation of severe-phenotype transgenic tobacco plants treated with GA53 or GA20. Ten microliters of a 10 or 100 μm solution of GA53 or GA20 in 5% acetone was applied to the shoot apex of severe-phenotype transformants once a week.

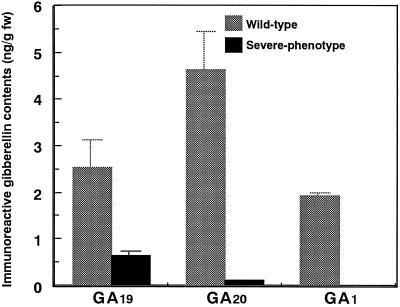

Contents of GA1 Precursors in Severe-Phenotype Tobacco Plants

The GA19, GA20, and GA1 contents of wild-type and severe-phenotype transgenic tobacco plants were analyzed to confirm that OSH1 could suppress GA 20-oxidase activity in transformants (Fig. 3). The content of GA19, a mid-product of GA 20-oxidase, was decreased to 25% of that observed in wild-type plants. In contrast, GA20, an end product of GA 20-oxidase, was reduced to a very low level, similar to that of GA1. These observations strongly suggest that OSH1 overexpression leads to a decrease in GA1 content by suppressing GA 20-oxidase activity in transgenic tobacco.

Figure 3.

Levels of GA19, GA20, and GA1 in leaves of wild-type and severe-phenotype OSH1-transformed tobacco plants. fw, Fresh weight.

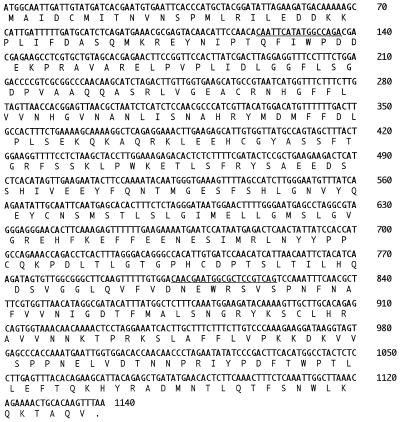

Cloning of a Tobacco GA 20-Oxidase cDNA

Plant GA 20-oxidase genes have recently been isolated from several species, e.g. pumpkin (Lange et al., 1994), Arabidopsis (Phillips et al., 1995; Xu et al., 1995), spinach (Wu et al., 1996), pea (Martin et al., 1996), and French bean (García-Martínez et al., 1997). We used degenerate primers based on conserved regions of the GA 20-oxidase genes (Fig. 4) to amplify a fragment of the GA 20-oxidase gene from tobacco. Sequence analysis revealed that the 720-bp fragment obtained by PCR encoded a polypeptide that was 77% identical and 88% similar to the GA 20-oxidase inferred from the French bean gene (García-Martínez et al., 1997). The 720-bp PCR product was used to screen a tobacco cDNA library constructed using mRNA isolated from vegetative stem tissue. Several positive clones were identified from the 2.4 × 105 recombinant library. Plasmids containing the inserts of the clones were obtained by in vivo rescue. Restriction endonuclease digestion showed that one of these clones contained a 1.5-kb insert, the expected size for a full-length GA 20-oxidase cDNA clone. DNA sequencing revealed that the insert of this cDNA clone contained the sequence of the 720-bp PCR product and possessed an open reading frame encoding 379 amino acids (Fig. 4), indicating that it represented a full-length clone. The deduced amino acid sequence of this cDNA showed 74%, 66%, and 50% identity to those of GA 20-oxidase cloned from French bean (Pv15–11; García-Martínez et al., 1997), Arabidopsis (At2301; Phillips et al., 1995), and pumpkin (Cm20ox; Lange et al., 1994), respectively. From these results, the 1.5-kb cDNA appeared to represent a full-length clone of tobacco GA 20-oxidase.

Figure 4.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of tobacco GA 20-oxidase cDNA. Regions corresponding to the degenerate primers used in PCR amplification are underlined.

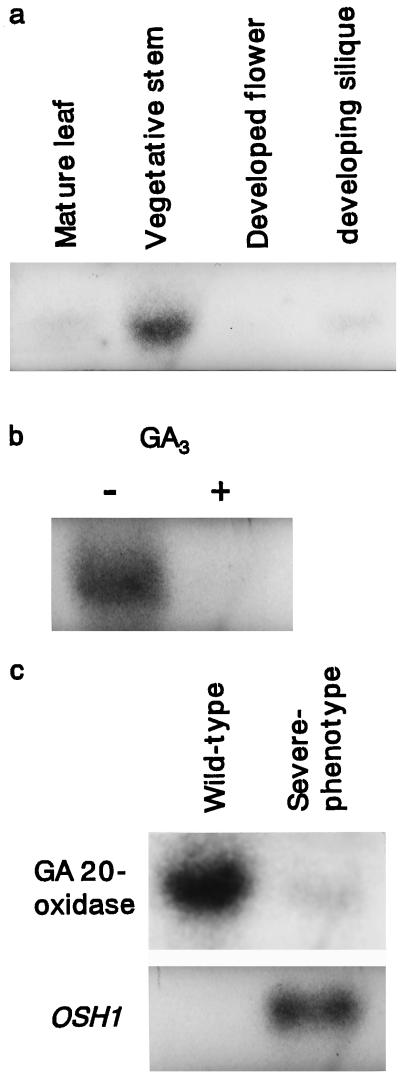

Expression Analysis of Tobacco GA 20-Oxidase

To investigate the expression of the putative tobacco GA 20-oxidase gene, RNA-blot hybridization was performed. Ten micrograms of total RNA extracted from mature leaves, vegetative stems, developed flowers, and developing siliques was probed with the 32P-labeled full-length tobacco GA 20-oxidase cDNA. Accumulation of tobacco GA 20-oxidase mRNA was seen mainly in stem tissue, with relatively low levels detected in RNA from leaves, siliques, and flowers (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5.

RNA-blot analysis of GA 20-oxidase gene expression. 32P-Labeled GA 20-oxidase cDNA or XbaI/SacI fragment of OSH1 cDNA was hybridized with 10 μg of total RNA extracted from mature leaves, vegetative stem, developed flowers, and developing siliques (a), and stem tissue treated without (−) or with (+) 100 μm GA3 for 8 h (b), and stem tissue of wild-type (left) and severe-phenotype OSH1-transformed (right) tobacco plants (c).

In stem tissue, treatment with GA3 8 h before RNA extraction reduced the abundance of tobacco GA 20-oxidase mRNA (Fig. 5b). Similar results have also been obtained in Arabidopsis (Phillips et al., 1995; Xu et al., 1995) and in pea (Martin et al., 1996).

Severe-phenotype transgenic tobacco plants expressing OSH1 showed extreme dwarfism. To confirm whether this dwarfism could be attributed to the suppression of GA 20-oxidase gene expression in stem tissue, we analyzed the abundance of GA 20-oxidase mRNA in stem tissue of severe-phenotype and wild-type tobacco plants. The GA 20-oxidase mRNA was substantially suppressed in severe-phenotype stems compared with wild-type stems (Fig. 5c).

DISCUSSION

Expression of the rice homeobox gene OSH1 causes morphological changes in transgenic tobacco, including dwarfism and loss of apical dominance (Kano-Murakami et al., 1993). In OSH1-transformed tobacco plants exhibiting a severe phenotype, hormone levels are altered, with a decrease of GA1 and increased levels of ABA and trans-zeatin (Kusaba et al., 1998). Many GA-responsive mutants showing dwarfism have been isolated from several species. These dwarf mutants show decreased bioactive GA levels, and their growth can be restored with applied bioactive GA (Hedden and Kamiya, 1997). Our recent finding that exogenous GA3 can correct the dwarfism in severe-phenotype tobacco plants expressing OSH1 indicates that these plants may represent GA-responsive dwarfs (Kusaba et al., 1998). The application of GA53 and GA20, precursors of GA1, to severe-phenotype tobacco transformants indicated that the biosynthetic pathway between GA53 and GA20 appears to be blocked in these plants (Fig. 2). The conversion of GA53 to GA20 is catalyzed by the multifunctional 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase GA 20-oxidase (Lange, 1994). In the GA-responsive semidwarf ga5 mutant of Arabidopsis (Koornneef and van der Veen, 1980), the contents of C19-GAs were reduced compared with the wild type (Talon et al., 1990). Xu et al. (1995) determined that the GA5 locus of Arabidopsis encodes GA 20-oxidase. Severe-phenotype tobacco plants also showed a drastic decrease of the C19-GAs GA20 and GA1 (Fig. 3). These observations suggest that overexpression of OSH1 in transgenic tobacco results in a suppression of GA 20-oxidase activity.

Because the OSH1 gene product contains a putative DNA-binding domain, the homeodomain, OSH1 is thought to control plant morphogenesis through the regulation of gene expression (Matsuoka et al., 1993). However, no target gene of OSH1 has yet been identified. These observations plus our current results indicate that overexpression of OSH1 may regulate GA 20-oxidase gene expression either directly or indirectly. To investigate this hypothesis, we cloned a tobacco cDNA encoding GA 20-oxidase. The amino acid sequence deduced from this full-length cDNA showed 74%, 66%, and 50% identity to those of GA 20-oxidase cloned from French bean (Pv15–11; García-Martínez et al., 1997), Arabidopsis (At2301; Phillips et al., 1995), and pumpkin (Cm20ox, Lange et al., 1994), respectively. GA 20-oxidases exhibit a relatively low degree of sequence conservation, with amino acid identities ranging from 50% to 75% (Hedden and Kamiya, 1997). Tobacco GA 20-oxidase gene expression was suppressed by GA application (Fig. 5b), as has been demonstrated in several other plant species (Phillips et al., 1995; Xu et al., 1995; Martin et al., 1996). These data indicate that the cDNA isolated from tobacco almost certainly encodes GA 20-oxidase.

The GA 20-oxidases are encoded by multiple genes in Arabidopsis (Phillips et al., 1995), pea, and French bean (García-Martínez et al., 1997). The GA 20-oxidase genes in Arabidopsis exhibit tissue-specific expression, leading to the belief that the various genes are responsible for GA biosynthesis associated with different aspects of plant development. The gene corresponding to the GA5 locus shows stem-specific expression, indicating that stem-specific GA 20-oxidases may be involved in stem elongation in Arabidopsis. The tobacco GA 20-oxidase gene was expressed mainly in developing stem tissue, with relatively low-level expression in leaves and siliques (Fig. 5a). Taken together, these results indicate that tobacco GA 20-oxidase may also be involved in stem elongation. We propose that the dwarfism of severe-phenotype transgenic tobacco plants may be due to the suppression of GA 20-oxidase gene expression (Fig. 5c).

Recently, a tobacco homeobox gene termed NTH15 (Nicotiana tabacum homeobox 15) was isolated and its homeodomain sequence shows 88% identity to that of OSH1 (Tamaoki et al., 1997). Ectopic expression of NTH15 in transgenic tobacco causes morphological changes that are in large part similar to those seen in OSH1 transformants. In transgenic tobacco expressing NTH15, a drastic decrease of GA1 content was also observed. In wild-type tobacco NTH15 gene expression was strongly expressed in vegetative stems and weakly expressed in shoot apices, flower buds, and flowers. These results imply that expression of NTH15 in stem tissue may be involved in stem elongation by regulating the expression of GA 20-oxidase.

The deduced amino acid sequence of OSH1 contains a homeodomain, leading us to propose that the OSH1 gene product controls plant morphogenesis through regulation of expression of certain target gene(s). However, little is known about the target genes of plant homeodomain-containing proteins. Our recent results suggest that OSH1 affects plant hormone metabolism either directly or indirectly, thereby causing changes in plant development (Kusaba et al., 1998). Our present results indicate that a developmental signal from the OSH1 protein may act to suppress GA 20-oxidase expression in transgenic tobacco. GA 20-oxidase expression has been reported to be developmental stage and organ specific, and to be regulated by end products and photoperiod (Hedden and Kamiya, 1997). However, the analysis of cis-elements and trans-factor(s) that regulate the expression of GA 20-oxidase genes has not yet been reported. Further work is needed to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms controlling GA 20-oxidase gene expression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Y. Ohashi (National Institute of Agrobiological Resources, Tsukuba, Japan) for kindly supplying us with wild-type tobacco plants, M. Nakajima and M. Hasegawa (University of Tokyo) for skillful technical assistance, and T. Maotani (National Institute of Fruit Tree Science) for helpful comments.

Footnotes

The accession number for the nucleotide sequence of tobacco GA 20-oxidase described in this article is AB012856.

LITERATURE CITED

- García-Martínes JL, López-Diaz I, Sánchez-Beltrán MJ, Phillips AL, Ward DA, Gaskin P, Hedden P. Isolation and transcript analysis of gibberellin 20-oxidase genes in pea and bean in relation to fruit development. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;33:1073–1084. doi: 10.1023/a:1005715722193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring WJ. Homeo boxes in the study of development. Science. 1987;236:1245–1252. doi: 10.1126/science.2884726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hake S, Vollbrecht E, Freeling M. Cloning Knotted, the dominant morphological mutant in maize using Ds2 as a transposon tag. EMBO J. 1989;8:15–22. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P, Kamiya Y. Gibberellin biosynthesis: enzymes, genes and their regulation. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:431–460. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano-Murakami Y, Yanai T, Tagiri A, Matsuoka M. A rice homeotic gene, OSH1, causes unusual phenotype in transgenic tobacco. FEBS Lett. 1993;334:365–368. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter R, Vollbrecht E, Lowe B, Veit B, Yamaguchi J, Hake S. Sequence analysis and expression patterns divide the maize knotted1-like homeobox genes into two classes. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1877–1887. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.12.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M, van der Veen JH. Induction and analysis of gibberellin-sensitive mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Theor Appl Genet. 1980;58:257–263. doi: 10.1007/BF00265176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusaba S, Kano-Murakami Y, Matsuoka M, Fukumoto M. A rice homeobox containing gene altered morphology of tobacco and kiwifruit. Acta Hortic. 1995;392:203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Kusaba S, Kano-Murakami Y, Matsuoka M, Tamaoki M, Sakamoto T, Yamaguchi I, Fukumoto M. Alteration of hormone levels in transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing a rice homeobox gene OSH1. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:471–476. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange T. Purification and partial amino-acid sequence of gibberellin 20-oxidase from Cucurbita maxima L. endosperm. Planta. 1994;195:108–115. doi: 10.1007/BF00206298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange T, Hedden P, Graebe JE. Expression cloning of a gibberellin 20-oxidase, a multifunctional enzyme involved in gibberellin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8552–8556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DN, Proebsting WM, Parks TD, Dougherty WG, Lange T, Lewis MJ, Gaskin P, Hedden P. Feed-back regulation of gibberellin biosynthesis and gene expression in Pisum sativum L. Planta. 1996;200:159–166. doi: 10.1007/BF00208304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M, Ichikawa H, Saito A, Tada Y, Fujimura T, Kano-Murakami Y. Expression of a rice homeobox gene causes altered morphology of transgenic plants. Plant Cell. 1993;5:1039–1048. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.9.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murofushi N, Shigematsu Y, Nagura S, Takahashi N. Metabolism of steviol and its derivatives of Gibberella fujikuroi. Agric Biol Chem. 1982;46:2305–2311. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, Yamaguchi I, Nagatani A, Kizawa S, Murofushi N, Furuya F, Takahashi N. Monoclonal antibodies specific for non-derivatized gibberellins. I. Preparation of monoclonal antibodies against GA4 and their use in immunoaffinity chromatography. Plant Cell Physiol. 1991;32:515–521. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AL, Ward DA, Uknes S, Appleford NEJ, Lange T, Huttly AK, Gaskin P, Graebe JE, Hedden P. Isolation and expression of three gibberellin 20-oxidase cDNA clones from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:1049–1057. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.3.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MP, Tamkun JW, Hartzell GW. The structure and function of the homeodomain. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1989;989:25–48. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(89)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talon M, Koornneef M, Zeevaart JAD. Endogenous gibberellins in Arabidopsis thaliana and possible steps blocked in the biosynthetic pathways of the semidwarf ga4 and ga5 mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7983–7987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaoki M, Kusaba S, Kano-Murakami Y, Matsuoka M. Ectopic expression of a tobacco homeobox gene, NTH15, dramatically alters leaf morphology and hormone levels in transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell Physiol. 1997;38:917–927. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K, Li L, Gage DA, Zeevaart JAD. Molecular cloning and photoperiod-regulated expression of gibberellin 20-oxidase from the long-day plant spinach. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:547–554. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.2.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y-L, Li L, Wu K, Peeters AJM, Gage DA, Zeevaart JAD. The GA5 locus of Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a multifunctional gibberellin 20-oxidase: molecular expression and functional expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6640–6644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi I, Nakagawa R, Kurogochi S, Murofushi N, Takahashi N, Weiler EW. Radioimmunoassay of gibberellins A5 and A20. Plant Cell Physiol. 1987;28:815–824. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi I, Nakajima M, Kanazawa K, Mander LN, Murofushi N, Takahasi N. Preparation and application of antibodies for non-derivatized gibberellins. In: Karssen CM, van Loon LC, Vreugdenhill D, editors. Progress in Plant Growth Regulation. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1992. pp. 874–882. [Google Scholar]