Abstract

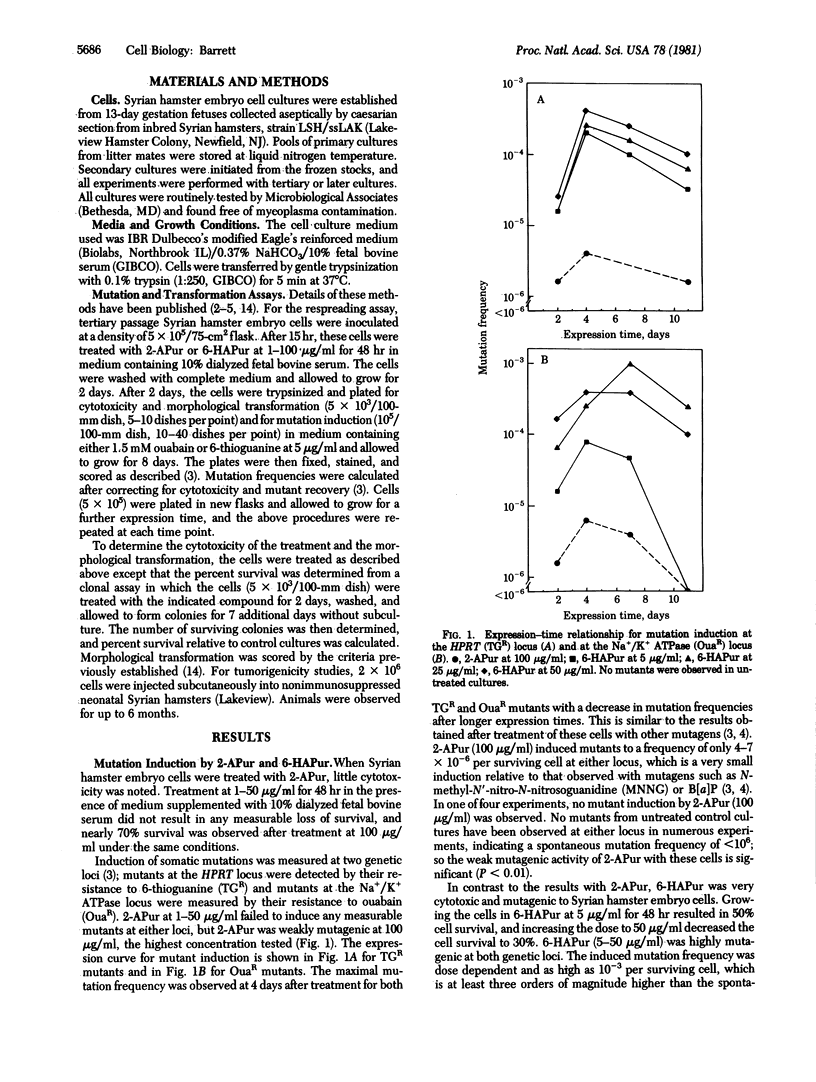

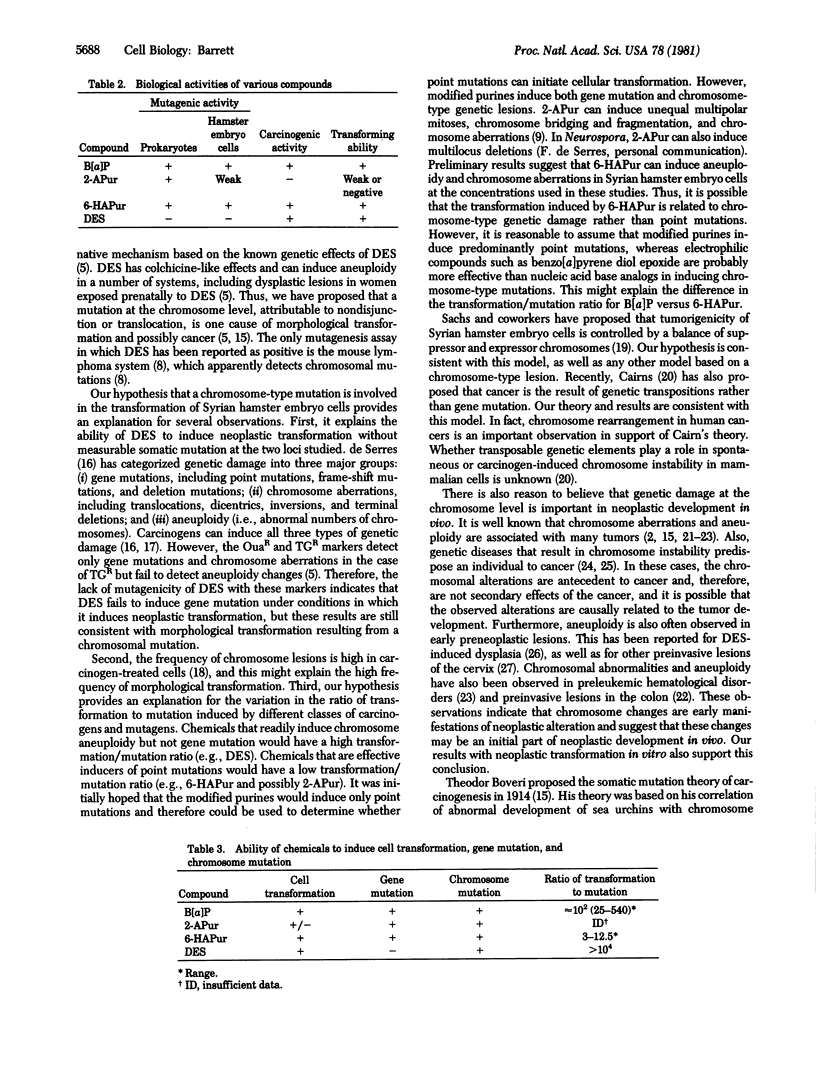

2-Aminopurine, a classical mutagen in prokaryotic systems, is inactive as a carcinogen in two animal species. To determine the basis for this discrepancy in the correlation between carcinogenesis and mutagenesis, the ability of 2-aminopurine to induce somatic mutation and neoplastic transformation concomitantly in the same cellular system was examined. 6-N-hydroxylaminopurine, a related modified purine that is a mutagen and a carcinogen, was also studied. 2-Aminopurine was a mutagen in Syrian hamster embryo cells, but its activity was very weak. The maximum induced mutation frequency with either of two mutational markers was only 7 X 10(-6) mutants per surviving cell. 2-Aminopurine also induced morphological transformation of the cells under the same conditions, but the frequency was only approximately 0.04% per surviving colony. Neoplastic transformation of the cells after 2-aminopurine treatment was not observed in these experiments. These results indicate that 2-aminopurine is, at best, a weak transforming agent. The lack of carcinogenic activity in vivo with 2-aminopurine is consistent with these observations. In contrast to the results with 2-aminopurine, 6-N-hydroxylaminopurine was a very effective mutagen in these cells (up to 10(-3) mutants per survivor) and induced morphological transformation of the cells in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, neoplastic transformation was induced by this nucleic acid base analog. The correlation of mutagenic activity with transforming ability of these two modified purines supports a relationship between mutagenesis and carcinogenesis. However, relative to other carcinogens, there is a quantitative difference in the ability of 6-N-hydroxylaminopurine to induce cell transformation and mutation. For example, in benzo[a]pyrene-treated cultures, the ratio of the frequency of induced morphological transformation to that of somatic mutation was approximately 100, whereas for 6-N-hydroxylaminopurine-treated cultures, the ratio of transformation to mutation was only 3-12.5. This indicates that 6-N-hydroxylaminopurine is less potent than benzo[a]pyrene in inducing transformation when compared at equal mutagenic potency. This is consistent with our hypothesis that cell transformation, and possibly cancer, occurs predominantly as the result of a mutation at the chromosome level rather than a gene mutation.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barrett J. C., Bias N. E., Ts'o P. O. A mammalian cellular system for the concomitant study of neoplastic transformation and somatic mutation. Mutat Res. 1978 Apr;50(1):121–136. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(78)90067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J. C., Ts'o P. O. Evidence for the progressive nature of neoplastic transformation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Aug;75(8):3761–3765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J. C., Ts'o P. O. Relationship between somatic mutation and neoplastic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Jul;75(7):3297–3301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J. C., Wong A., McLachlan J. A. Diethylstilbestrol induces neoplastic transformation without measurable gene mutation at two loci. Science. 1981 Jun 19;212(4501):1402–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.6262919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict W. F. Early changes in chromosomal number and structure after treatment of fetal hamster cultures with transforming doses of polycyclic hydrocarbons. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1972 Aug;49(2):585–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockman H E, de Serres F J. Induction of ad-3 Mutants of Neurospora Crassa by 2-Aminopurine. Genetics. 1963 Apr;48(4):597–604. doi: 10.1093/genetics/48.4.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns J. The origin of human cancers. Nature. 1981 Jan 29;289(5796):353–357. doi: 10.1038/289353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clive D., Johnson K. O., Spector J. F., Batson A. G., Brown M. M. Validation and characterization of the L5178Y/TK+/- mouse lymphoma mutagen assay system. Mutat Res. 1979 Jan;59(1):61–108. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(79)90195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freese E. B. The mutagenic effect of hydroxyaminopurine derivatives on phage T4. Mutat Res. 1968 Mar-Apr;5(2):299–301. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(68)90028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y. S., Reagan J. W., Richart R. M., Townsend D. E. Nuclear DNA and histologic studies of genital lesions in diethylstilbestrol-exposed progeny. I. Intraepithelial squamous abnormalities. Am J Clin Pathol. 1979 Oct;72(4):503–514. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/72.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German J. Genes which increase chromosomal instability in somatic cells and predispose to cancer. Prog Med Genet. 1972;8:61–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janion C. The efficiency and extent of mutagenic activity of some new mutagens of base-analogue type. Mutat Res. 1978 Jan;56(3):225–234. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(78)90189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann J., Ames B. N. Detection of carcinogens as mutagens in the Salmonella/microsome test: assay of 300 chemicals: discussion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976 Mar;73(3):950–954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.3.950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronen A. 2-Aminopurine. Mutat Res. 1980 Jan;75(1):1–47. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(80)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura K., Teller M. N., Parham J. C., Brown G. B. A comparison of the oncogenicities of 3-hydroxyxanthine, guanine 3-N-oxide, and some related compounds. Cancer Res. 1970 Jan;30(1):184–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAININ N., KAYE A. M., BERENBLUM I. INFLUENCE OF MUTAGENS ON THE INITIATION OF SKIN CARCINOGENESIS. Biochem Pharmacol. 1964 Feb;13:263–267. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(64)90144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T., Rabinowitz Z., Sachs L. Identification of the chromosomes that control malignancy. Nat New Biol. 1973 Jun 20;243(129):247–250. doi: 10.1038/newbio243247a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Serres F. J. Problems associated with the application of short-term tests for mutagenicity in mass-screening programs. Environ Mutagen. 1979;1(3):203–208. doi: 10.1002/em.2860010302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]