Abstract

There are at least two obvious features that must be considered upon targeting specific metabolic pathways/enzymes for drug development: the pathway must be essential and the enzyme must allow the design of pharmacologically useful inhibitors. Here, we describe Trypanosoma cruzi sterol 14α-demethylase as a promising target for anti-Chagasic chemotherapy. The use of anti-fungal azoles, which block sterol biosynthesis and therefore membrane formation in fungi, against the protozoan parasite has turned out to be highly successful: a broad spectrum anti-fungal drug, the triazole compound posaconazole, is now entering phase II clinical trials for treatment of Chagas disease. This review summarizes comparative information on anti-fungal azoles and novel inhibitory scaffolds selective for Trypanosomatidae sterol 14α-demethylase through the lens of recent structure/functional characterization of the target enzyme. We believe our studies open wide opportunities for rational design of novel, pathogen-specific and therefore more potent and efficient anti-trypanosomal drugs.

4.1. INTRODUCTION

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) is the generic name for a superfamily of protoheme containing monooxygenases (Omura and Sato, 1964). There are about 12,000 members of this superfamily which increases in size as more genomes are sequenced (www.http://drnelson.utmem.edu/cytochromeP450.html). P450s can be most generally grouped into two classes, one which inactivates xenobiotics and the other which is necessary for biosynthesis of endogenous compounds. The general reaction catalysed by P450s is seen below, where SH indicates substrate and 2e− indicates reducing equivalents from NADH or NADPH.

P450s are found in a large number of organisms through all biological kingdoms. The only specific form found in all biological kingdoms is the sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51 family), an essential enzyme in sterol biosynthesis and therefore membrane structure. Some investigators have suggested that CYP51 is the oldest of the known P450s (Yoshida et al., 2000).

Inhibition of CYP51 activity has been found to be lethal in organisms requiring sterol biosynthesis for membrane function (Lepesheva and Waterman, 2007). Initial studies of CYP51 inhibitory drugs were carried out topically in fungi and yeast infections on the skin, such as athletes foot. Subsequently, systemic treatment of such infections has been necessary, for example, Candida albicans or Aspergillus spp. infection in HIV/AIDS or in other immunosuppressed states such those attending cancer chemotherapy or organ transplantation. Effective systemic treatment should be specific for the CYP51 of the infectious pathogen, not the host (human). Our studies have found that members of the genera Trypanosoma and Leishmania can be killed by CYP51 inhibitors. Three features of inhibition of Trypanosoma cruzi are presented in this chapter. First, we will present studies on inhibition of T. cruzi CYP51 enzymatic activity. Second, structural studies of CYP51 will be used to explain the way that azole compounds can inhibit T. cruzi CYP51 activity. Third, we will summarize results from anti-parasitic effects in T. cruzi. Finally, we will show why CYP51 inhibition is such a promising treatment for T. cruzi infection and present chemical scaffolds for development of additional drugs.

4.2. STEROL BIOSYNTHESIS

Eukaryotic organisms require sterols (Benveniste, 1986; Schaller, 2003; Schroepfer, 1981). The sterols, such as cholesterol in animals, sitosterol in plants or ergosterol in fungi, are essential structural components of eukaryotic membranes, regulating their fluidity and permeability (Haines, 2001). In addition, sterols serve as precursors for biologically active molecules that regulate growth and development processes. The sterols are either produced solely endogenously (plants, the majority of fungi, T. cruzi; Docampo et al., 1981; Beach et al., 1986; Haughan and Goad, 1991; Liendo et al., 1999; Leishmania) or must be acquired from the diet (insects, some fungi and protists). Many species, including mammals (humans), yeasts or Trypanosoma brucei, can utilize both endogenous and exogenous sources to fulfil the requirement for bulky structural sterols but only endogenously made molecules are further converted into species-specific regulatory sterols (Lepesheva et al., 2010b).

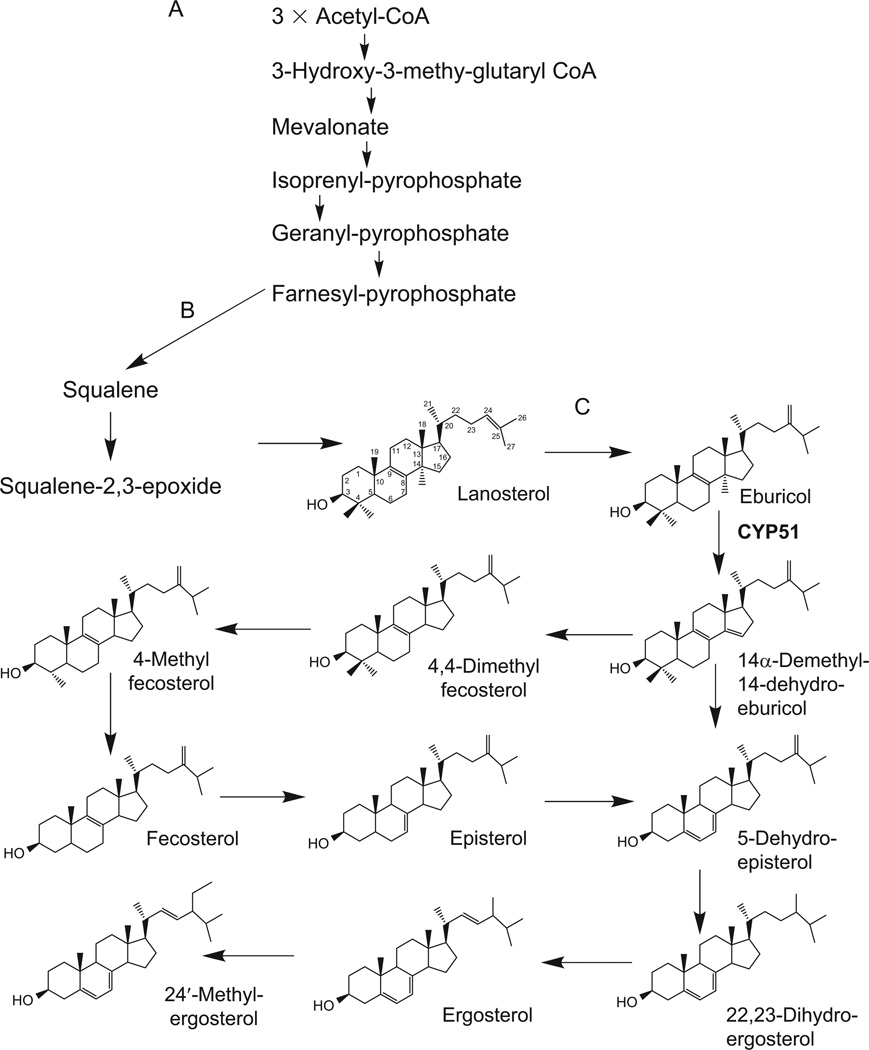

Sterol biosynthesis can be considered as a “eukaryotic extension” of the mavalonate pathway (Rohmer et al., 1979; Volkman, 2005). The mavalonate pathway begins anaerobically, with acetyl-CoA condensation, and proceeds via several intermediates to produce farnesyl pyrophosphate (Fig. 4.1A). Farnesyl pyrophosphate can serve as precursor in various biological processes (Goldstein and Brown, 1990). In the first step of committed sterol biosynthesis, farnesyl pyrophosphate forms squalene (Fig. 4.1B). In the presence of molecular oxygen, the latter is transformed into squalene 2,3-epoxide. Opposite to plants/algae, where squalene 2,3-epoxide is converted into cycloartenol, animals, fungi and Trypanosomatidae cyclyse it into lanosterol (Lepesheva and Waterman, 2007). Further, reactions on the lanostane skeleton include demethylations of the sterol core and modifications of the sterol B ring and C20–27 arm.

FIGURE 4.1.

Sterol biosynthetic pathway in T. cruzi. (A) Mevalonate portion. (B) First eukaryote-specific steps. (C) T. cruzi-specific steps.

In T. cruzi (Fig. 4.1C), lanosterol is first converted into eburicol (C24-methylene-24, 25-digydrolanosterol), which is the preferred substrate of T. cruzi sterol 14α-demethylase (Lepesheva et al., 2006b). The 14α-demethylated product of CYP51 reaction is then reduced to 4,4-dimethyl-fecosterol and C4-demethylated into fecosterol. Rearrangement of the double bond in ring B from ΔC8–9 to ΔC7–8 position produces episterol; introduction of the double bond at C5–6 gives 5-dehydro-episterol. The C24-methylene group of 5-dehydro-episterol is saturated forming 22,23-dihydro-egrosterol; its desaturation at ΔC22–23 results in formation of ergosterol, which together with its C24 methylated analog represent the major final products of the pathway (Urbina et al., 1998, 2003a,b). It has been reported, however, that T. cruzi amastigotes lack ΔC5 and ΔC22 desaturase activity and therefore the major sterol products of this intracellular form of the parasite appear to be episterol and two C5–6, C22–23 saturated analogs of ergosterol and 24′-methyl-ergosterol (ergosta-7-en-3b-ol and 24′-methyl-ergosta-7-en-3b-ol, respectively; Liendo et al., 1998, 1999).

In higher eukaryotes, sterol biosynthesis occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum, and major sterols are concentrated in the plasma membranes, while in Trypanosomatidae the endogenously produced sterols as well as several sterol biosynthetic enzymes are also found in the membranes of glycosomes and mitochondria, suggesting a possibility of multi-organelle location of the sterol biosynthetic pathway in the parasites (Pena-Diaz et al., 2004; Quinones et al., 2004; Rodrigues et al., 2001). The reasons for the possible broader subcellular distribution of the pathway remain to be understood, yet it might support multiple functions of endogenous sterols in these protozoa.

4.3. POTENTIAL DRUG TARGETS IN THE PATHWAY

The fact that T. cruzi is entirely dependent on endogenously produced sterols for survival and proliferation and cannot use the supply of host cholesterol makes the sterol biosynthetic pathway in the parasite especially attractive for drug development. There are several enzymes in the pathway that have potential to serve as future targets for anti-trypanosomal chemotherapy. The most apparent examples are HMG-CoA reductase, which in humans is the clinical target for statins (Puccetti et al., 2007), farnesyl diphosphate synthase, the target for bisphosphonates (Kavanagh et al., 2006), squalene synthase, which is inhibited by quinuclidine derivatives (Cammerer et al., 2007), sterol 24-methyltransferase inhibited by azasterols (Gros et al., 2006; Magaraci et al., 2003) and sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51).

The major advantage of sterol 14α-demethylase is connected with its high druggability. Inhibitors of this enzyme (azoles) are the most efficient anti-fungal agents in clinical medicine and in agriculture (Petrikkos and Skiada, 2007; Zonios and Bennett, 2008). In addition to blocking sterol biosynthesis, the potency of azoles is enhanced by accumulation of toxic methylated sterol precursors that also promote fungal growth arrest and deleterious changes in the membrane permeability (Cournia et al., 2007; Nes, 1974; Yeagle et al., 1977). Anti-parasitic effects of anti-fungal azoles in T. cruzi have been observed by multiple investigators, the first reports being published in 1981 (Araujo et al., 2000; Beach et al., 1986; Docampo et al., 1981; Molina et al., 2000; Urbina et al., 1988, 2000). Several of them, including posaconazole, were proven to have curative effect in both acute and chronic forms of Chagas disease in animal models (Apt et al., 1998; Urbina, 2009; Urbina et al., 1996, 2003a,b). Finally, this year, after it cured chronic Chagas disease in an immunosuppressed patient in Barcelona (Pinazo et al., 2010), posaconazole has been reported to enter phase II clinical trial for Chagas disease in Spain (Clayton, 2010). Another azole, ravuconazole, which is currently under phase II clinical trials as an anti-fungal agent, is considered by the Drug for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi) as an option for clinical development for Chagas disease treatment (Clayton, 2010), even though it only has a suppressive effect on the parasite in vivo (Diniz Lde et al., 2010).

Until recently, when it became a global problem due to human migration, blood bank/organ transplant contaminations and HIV coinfections, Chagas disease predominantly threatened lives of the poorest. Therefore, low investment into Chagas drug discovery research, lack of serious interest from pharmaceutical companies, as well as long-term domination of the autoimmune hypothesis of chronic Chagas disease pathogenesis which underscored the notion that causative treatment would not be beneficial (Urbina, 2010) significantly impeded implementation of the therapeutic use of the azoles obtained from anti-fungal drug development programs let alone development of new T. cruzi sterol 14α-demethylase specific therapies. However, the fact that sterol 14α-demethylases from Trypanosomatidae have only 22–26% amino acid sequence identity to the fungal CYP51 orthologs (Lepesheva and Waterman, 2011) clearly suggests that more effective inhibitors of the protozoan enzyme remain to be found.

4.4. TRYPANOSOMA CRUZI STEROL 14α-DEMETHYLASE (CYP51)

4.4.1. Reaction and catalysis

T. cruzi sterol 14α-demethylase (EC: 1.14.13.70, CYP51 gene family) is a CYP monooxygenase that catalyses removal of the 14α-methyl group from eburicol (Fig. 4.2). As all cytochromes P450, CYP51 contains a haem cofactor (protoporphyrin IX), where the iron in its fifth (axial) coordination position is tethered to the proximal side of the protein via a thiolate ligand derived from a cysteine residue (Cys422 in T. cruzi CYP51). This iron-cysteine coordination is responsible for the P450 name that originated from the spectral property of the reduced enzyme to produce a characteristic absorbance maximum at 450 nm upon binding of carbon monoxide (Omura and Sato, 1964). The cysteine is a better electron donor than histidine, the residue that is coordinated to the haem iron in the majority of other haemoproteins, and this allows P450s to function as monooxygenases catalysing scission of molecular oxygen. As a result of P450 catalysis, one atom of oxygen is incorporated into an organic compound, sterol substrate in the case of CYP51, while another is released as a water molecule.

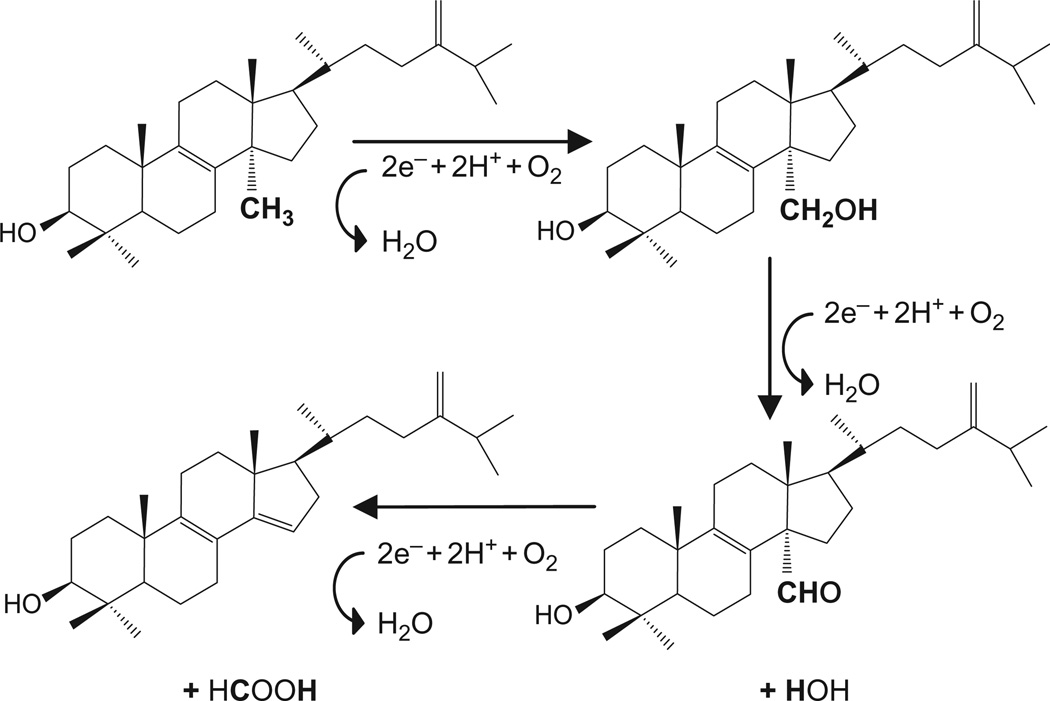

FIGURE 4.2.

Three-step catalytic reaction of T. cruzi CYP51. Each step requires molecular oxygen, two electrons and two catalytic protons. The 14α-methyl group of eburicol is converted into first the alcohol, second the aldehyde and third removed as formic acid. The substrates of CYP51s from other biological kingdoms are all structurally very similar. Eburicol also serves as the substrate for sterol 14α-demethylases in filamentous fungi. Plant and T. brucei orthologs metabolize its C4-monomethylated analog obtusifoliol. Lanosterol and 24,25-dihydrolanosterol, both lacking the methylene group at C24, are the natural substrates for the human (mammalian) enzyme.

The CYP51 reaction includes three CYP catalytic cycles. When the sterol substrate, most likely entering through the membrane, binds in the enzyme active site in such a way that the 14α-methyl group is positioned about 5 Å above the haem iron plane, the P450 accepts the first electron from cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR), and its haem iron is reduced from the resting ferric (Fe3+) to the active ferrous (Fe2+) state. Delivery of the first electron enables binding of an oxygen molecule in the sixth coordination position of the reduced iron, perpendicular to the haem plane and in close proximity to the sterol 14α-methyl group. After this, the second electron is transferred by CPR, reducing the haem bound oxygen. Then two catalytic protons arrive from the cytoplasm-exposed protein surface causing the oxygen scission and release of one water molecule while introducing the other atomic oxygen into the methyl group of the sterol (—C—H → —C—O—H). The second cycle of catalysis converts the 14α-alcohol group into the 14α-aldehyde; the third cycle results in release of formic acid and introduction of the Δ14-15-double bond into the sterol ring D.

4.4.2. Spectral responses to ligand binding

4.4.2.1. Ligand-induced shift in the Soret band maximum

Having the haem as an active cofactor, P450s are known to be competitively inhibited by heterocyclic compounds such as pyridine, pyrimidine and especially azole derivatives (Ortiz de Montellano and Correia, 1995). A basic atom from the heterocyclic ring coordinates directly to the haem iron, while the rest of the molecule occupies the active site cavity affecting substrate binding/metabolism. Such interactions can be recorded spectrally, serving as a useful tool to screen for new CYP51 inhibitors (Lepesheva et al., 2007). The principle for the optical screening is as follows: in the substrate-free state the haem in CYP51 is always hexacoordinated, a water molecule being bound to the iron as the sixth ligand (Lepesheva et al., 2010b). When a stronger ligand replaces the water molecule in the iron 6th coordination position, it causes a red shift in the Soret band maximum from 417 to 422–427 nm, also known as type II spectral response.

The same approach can also be used to estimate apparent affinity of the CYP51 interaction with substrate analogs. Although substrates or structurally related compounds do not bind to the haem iron directly, their binding expels the water molecule from the iron coordination sphere. As a result, they induce transition of the iron from the hexacoordinated low spin to the pentacoordinated high-spin state, the interaction being monitored as a blue shift in the Soret band maximum (from 417 to 390 nm), or type I spectral response.

Upon searching for anti-protozoan CYP51 inhibitors, however, we faced two limitations of the spectral titration. First, in some cases, the apparent binding parameters determined by titration do not correlate with the inhibitory effects of the compounds in the reconstituted enzyme reaction (Lepesheva et al., 2007, 2008). Second, especially strong CYP51 inhibitors (tight-binding ligands with the Kds < 0.1 µM) cannot be distinguished at standard conditions.

4.4.2.2. CO binding spectra

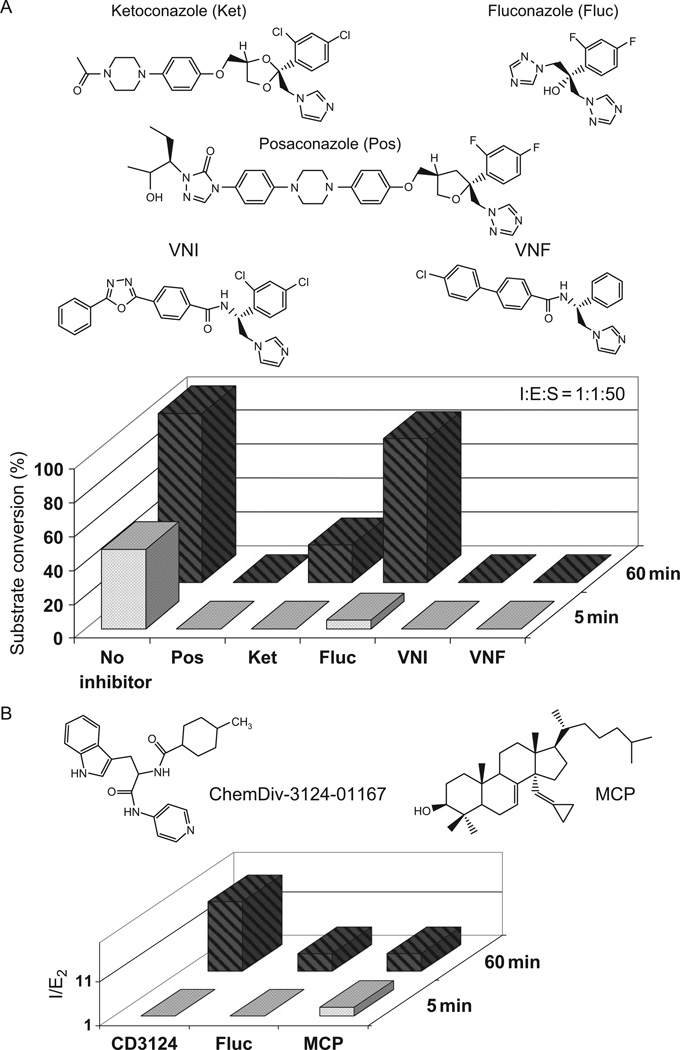

As an alternative, to estimate relative affinities of inhibitors to T. cruzi CYP51, we suggest to monitor their influence on the formation of the reduced P450-CO complexes (Lepesheva et al., 2010a). This approach appears to be rather sensitive, since it reflects the ability of carbon monoxide to replace the inhibitors from the iron coordination sphere when the enzyme is in the reduced, reactive state. We found that while weaker inhibitors such as fluconazole and ketoconazole decrease the rate of T. cruzi CYP51-CO-complex formation, VNI and VNF (see Section 4.5.1, and Fig. 4.3A) completely prevent CO-iron coordination.

FIGURE 4.3.

Selected inhibitors and their effects on T. cruzi CYP51 activity. (A) Anti-fungal and experimental azoles; I : E : S, molar ratio inhibitor/enzyme/substrate. (B) Non-azole compounds; I/E2, inhibitor/enzyme ratio that causes a twofold decrease in activity.

4.4.3. Reconstituted activity in vitro

Based on our experience, the most reliable method to evaluate potency of a compound as a CYP51 inhibitor is to test its effect on the enzyme activity in the in vitro reconstituted CYP51 reaction. Even this approach has its limitations (Lepesheva et al., 2007), the major problem being due to the IC50 detection limit. In traditional enzymology, the IC50 values were introduced to quantify inhibition of water soluble enzymes, the catalysts that are meant to be used at very low concentrations with very high molar excess of substrate. However, eukaryotic CYP51s are membrane bound highly hydrophobic proteins, which metabolize highly hydrophobic sterol substrates of extremely low solubility in water. An efficient system for reconstitution of CYP51 activity in vitro (catalytic turnover of T. cruzi CYP51 at these conditions is about 5 nmol/nmol/min) requires (1) the electron donor protein CPR, the Kd for the protein–protein complex being around 1 µM, (2) a phospholipid to incorporate the P450-CPR complex and (3) hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin to dissolve the sterol (Lepesheva et al., 2006b). This, together with the issues of enzyme stability, especially in the reactive, reduced (Fe2+) state restricts the option of decreasing the CYP51 concentration in the reaction. Therefore, we quantify effects of moderate inhibitors as I/E2 (molar ratio inhibitor/enzyme that causes a twofold decrease in the CYP51 turnover; Lepesheva et al., 2007), while in order to compare the most potent compounds we monitor the time-course of substrate conversion at equimolar ratio inhibitor/enzyme. As described below, the strongest Trypanosomatidae CYP51 inhibitors identified in this system prevent any conversion of the substrate over time thus acting not only as tight-binding but essentially as functionally irreversible inhibitors, their anti-parasitic effects in T. cruzi cells being in the lower nanomolar range.

4.5. INHIBITORS OF TRYPANOSOMA CRUZI CYP51

4.5.1. Anti-fungal drugs and experimental azole derivatives

The inhibitory effects of three anti-fungal drugs, ketoconazole, fluconazole and posaconazole, on the activity of T. cruzi CYP51 are included in Fig. 4.3A. Posaconazole (Zonios and Bennett, 2008), the drug soon to be in clinical trial for Chagas disease (Clayton, 2010; Urbina, 2010) is certainly the most potent amongst them. However, posaconazole is a complex compound, difficult to synthesize and therefore too costly to be expected to cure Chagas disease globally. Besides, it has significant toxicity and limited selectivity (I/E2 for human CYP51 is about 40; Lepesheva et al., 2010a). Due to its side effects, most common of which include nausea, vomiting, headache, abdominal pain and diarrhoea (Nagappan and Deresinski, 2007; Petrikkos and Skiada, 2007; Schiller and Fung, 2007), posaconazole was approved by the FDA in the United States only in 2006, solely as a salvage therapy for invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients. Therefore, the task of finding additional drug candidates, especially those which would be specific to T. cruzi CYP51, remains extremely important.

We screened a large number of experimental compounds against purified T. cruzi CYP51, the best inhibitory scaffold being identified amongst the set of imidazole derivatives originally synthesized by the Novartis Research Institute (Vienna, Austria) (Lepesheva et al., 2007). These azoles completely inhibit T. cruzi CYP51 activity (VNI and VNF in Fig. 4.3A) and also show very high selectivity to CYP51s from other pathogenic organisms. Acting as rather strong inhibitors of the fungal ortholog (C. albicans), they do not affect human CYP51, I/E2 > 200 (Lepesheva et al., 2010a,b). Accordingly, we found them to have low general cytotoxicity, EC50 > 50 µM (human leukaemia cell line HL60), while even at 1 µM they kill more than 99% of T. cruzi amastigotes (Lepesheva et al., 2007). Moreover, contrary to posaconazole or fluconazole, they do not enhance the T. cruzi CYP51 gene expression and do not require increase in the dosage to maintain constant cellular growth inhibition over time (Lepesheva and Waterman, 2011), which suggest their weaker propensity to induce resistance in the parasite.

Two other inhibitory scaffolds, disubstituted imidazoles and derivatives of the anti-cancer drug tipifarnib (triazole-based), were identified by Buckner et al. (Buckner et al., 2003; Hucke et al., 2005). In this case, the investigators originally observed strong anti-parasitic effects of the compounds with T. cruzi; analysis of parasite sterols has shown that they inhibit sterol 14α-demethylase. Testing these azoles in the reconstituted reaction confirmed their high inhibitory potencies and selectivity to the enzyme from T. cruzi (Kraus et al., 2009).

4.5.2. Non-azole inhibitors

Although azole derivatives remain the most potent CYP51 inhibitors identified so far, some of other non-azole types of compounds can also be considered as potential leads for the development of alternative therapies targeting T. cruzi sterol 14α-demethylase. One such example would be a pyridine derivative ChemDiv-3124-01167, which we identified via high-throughput screening (Lepesheva et al., 2008), the inhibitory effect and the formula can be seen in Fig. 4.3B. The compound shows clear anti-parasitic effects in T. cruzi, EC50 being ~7 µM (Konkle et al., 2009). Recently, our experiments with this inhibitor were reproduced at UCSF with very similar results (Chen et al., 2009). Furthermore, these authors report some curative effect of ChemDiv-3124-01167 in their murine model of the acute Chagas disease (Doyle et al., 2010).

CYP51 substrate analogs represent another opportunity for drug development. Inhibitory effects of several lanosterol derivatives on mammalian and yeast orthologs were described by several investigators (Aoyama et al., 1987; Cooper et al., 1988; Frye et al., 1993; Trzaskos et al., 1995; Tuck et al., 1991), one such compound was proven to act as a mechanism-based inhibitor of the enzyme (Bossard et al., 1991). So far we have tested only a limited number of substrate analogous compounds with T. cruzi CYP51 (Lepesheva et al., 2006b, 2008), Δ7-14α-methylenecyclopropyl-dihydrolanosterol (MCP), EC50 in T. cruzi cells ~5 µM being the best we have found (Fig. 4.3B). Recent determination of the structure of the complex of this sterol with CYP51 (PDB code 3P99, unpublished) opens new opportunities to enhance the inhibitory effects of this compound by further modifications. In general, a large number of diverse structures that can act as CYP51 inhibitors further confirm the highly druggable nature of these enzymes (Cheng et al., 2007).

4.6. STRUCTURAL BASIS FOR CYP51 DRUGGABILITY

Although, no doubt, highly potent, even species-specific CYP51 inhibitors can be found empirically, in the absence of a 3D structure of an eukaryotic CYP51 enzyme that functions in vivo as a sterol 14α-demethylase, it has been hard to comprehend what makes inhibitors particularly strong, what causes their selectivity or why the CYP51 propensity to be inhibited by azoles is generally much stronger than that of many other, especially drug-metabolizing P450s (Obach et al., 2006; Ortiz de Montellano and Correia, 1995; Wexler et al., 2004). Crystal structures of Trypanosomatidae CYP51 are helpful in answering these questions and also outline a general strategy for rational design of novel drugs for anti-trypanosomal chemotherapy.

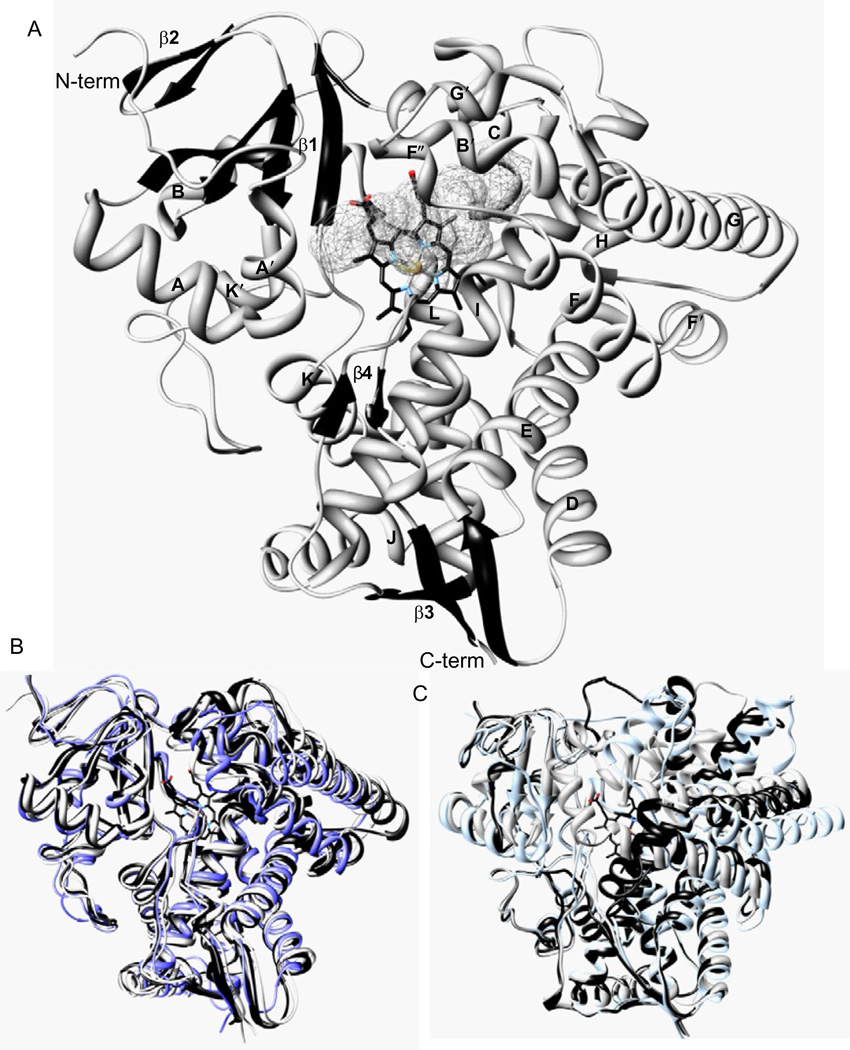

4.6.1. Overview of the CYP51 structure

Structurally, sterol 14α-demethylase has the characteristic P450 fold (Poulos et al., 1987), which from the distal view of the protein resembles an upside-down triangle (Fig. 4.4A). The set of the secondary structural elements includes 12 main helices, 10 additional, shorter helices between them and 12 β-strands assembled into four anti-parallel β-sheets; the helix/strand/coil ratio being about 50/10/30. Two nearly parallel “CYP core helices”, I and L, surround the haem from the distal and proximal sides, respectively. Helices A′, F″ and the top of the β4 hairpin on the upper left side of the distal surface of the protein are forming the entrance into the substrate access channel. In vivo, this highly hydrophobic portion of the protein molecule is predicted to be immersed into the endoplasmic reticulum membrane, receiving their sterol substrates through the lipid bilayer (Lepesheva et al., 2010b). About 6 × 9 Å wide at the beginning, the substrate access channel makes an angle of about 50° to the haem plane and runs about 20 Å to the haem iron, gradually broadening into the active site cavity inside the protein globule. The cavity is bordered by the haem (back), B′ helix/B′C loop (top), the N-terminal parts of helices C and I (right), β1-4 strand with the preceding K′/β1-4 loop (left and bottom, respectively) and β4 hairpin (front), the substrate binding surface being composed of 47 residues, including 43 side chains, as described in more detail in Section 4.6.3. The haem propionate side chains form hydrogen bonds with five dissociable amino acid residues, Y103, Y116, R124, R361 and H420, the haem iron is coordinated to C422.

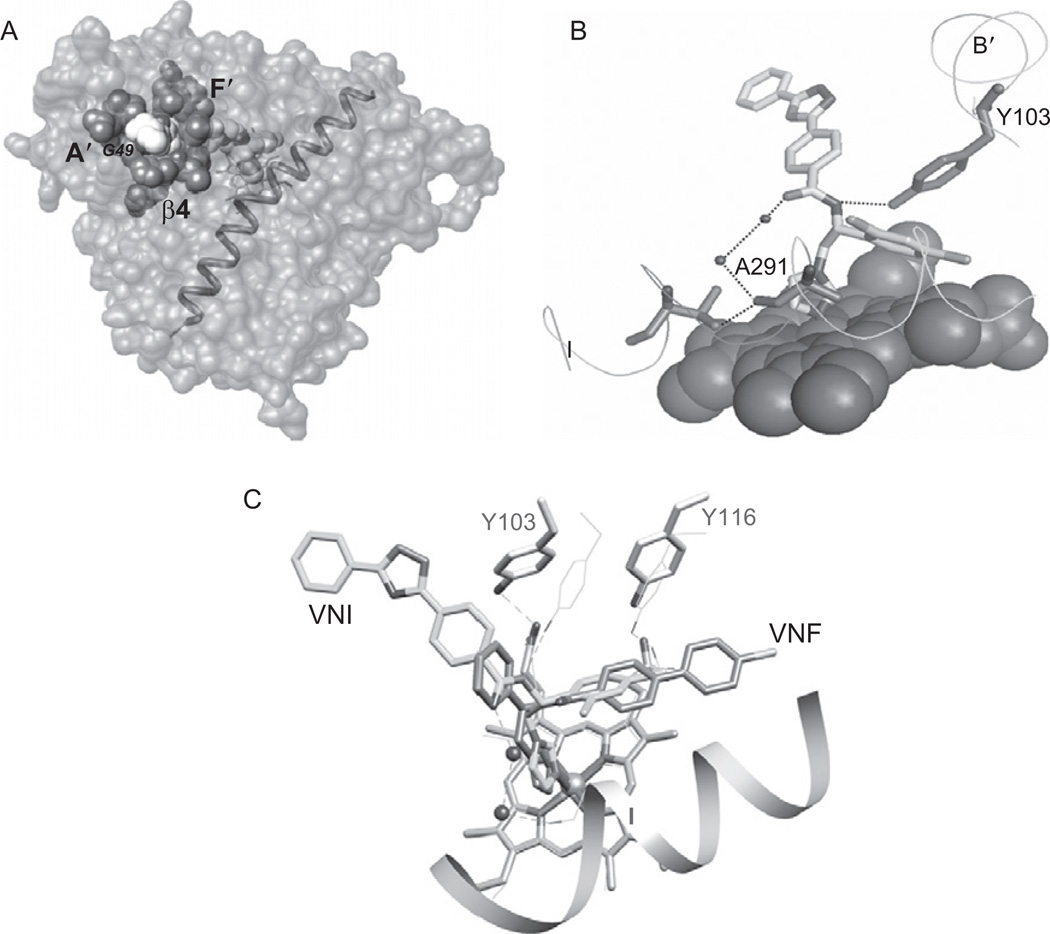

FIGURE 4.4.

CYP51 crystal structure. (A) Distal view, helices (grey) and β-sheets bundles (black) are shown in ribbon representation and marked. The haem is shown as a stick model. The active site cavity surface is depicted as the grey mesh. (B) Ligand-free T. brucei CYP51 (black) superimposed with VNI-bound T. brucei CYP51, posaconazole-bound T. cruzi (grey) and ketoconazole-bound human (dark grey) orthologs. Only minor alterations are seen in the CYP51 active site cavity area. (C) An example of a xenobioticmetabolizing P450, CYP2B4, in ligand-free form (black) and bound to two different ligands, 4-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazole and bifonazole (grey). Large-scale conformational changes significantly alter shape and volume of its active site pocket.

4.6.2. Specific structural features

Perhaps the most characteristic feature of the CYP51 structure is that the active site cavity does not change much, in shape or volume, both upon ligand binding and across species (Fig. 4.4B). The most flexible regions are presented by the GH loop, which is located on the P450 proximal surface, far away from the active site cavity and the FG-loop (including helix F″ that covers the entrance into the channel). In all three cases of azole-bound structures, it can be seen that the middle portion of the I-helix shifts slightly away from the haem, providing space for the heterocyclic ring to coordinate with the iron. On average, the r.m.s. deviation for all Cα atoms in the three T. cruzi CYP51 inhibitor complexes ranges only from 0.7 to 1.4 Å, and the r.m.s. deviation between the posaconazole-bound T. cruzi and ketoconazole-bound human CYP51s (27% amino acid sequence identity) is only 1.7 Å. Though at first quite surprising, this structural feature of CYP51 family members lead us to the conclusion that CYP51 enzymes appear to maintain their strict functional conservation (including the three-step catalytic reaction) by preserving high similarity at the secondary and tertiary structural levels (Lepesheva and Waterman, 2011).

This elevated rigidity of the substrate binding cavity appears to distinguish the CYP51 family from other CYPs, especially those involved in metabolism of xenobiotics (e.g. drug-metabolizing CYP families), whose structures are known to demonstrate high plasticity, allowing these enzymes to accommodate and metabolize a variety of chemical structures (CYP2B4 is shown in Fig. 4.4C as an example). On the contrary, CYP51 family members must preserve very strict substrate specificity, regardless of their low amino acid sequence identity across the biological kingdoms. High rigidity of the substrate binding cavity explains why a single amino acid substitution can completely inactivate the enzyme (Lepesheva et al., 2003) or switch its substrate preferences from C4-double- to C4-monomethylated sterols (Lepesheva et al., 2006a). Moreover, to fulfil their catalytic function, the enzymes must maintain their substrate properly oriented during the three steps of catalysis, which could be another reason for the requirement to have a rigid substrate binding site—a real “cavity” instead of flexible “pockets” typical for highly promiscuous CYPs. Most relevant here, the rigidity of the substrate binding cavity might be the basis for the experimentally proven elevated susceptibility of CYP51 to azole inhibitors. Next we will discuss how CYP51 structure can be helpful for drug development, in order to increase their (a) potency and (b) selectivity.

4.6.3. Structural explanation for the potencies of selected inhibitors

CYP51 complexes with the three most potent inhibitors, posaconazole [3K1O], VNI [3GW9] and VNF [3KSW], will be analysed here as examples (Fig. 4.5). As all azole inhibitors, the compounds coordinate to the CYP51 haem iron. It is well known, however, that Fe–N coordination alone is insufficient to make a strong inhibitor: small molecules, like imidazole or phenylimidazole, have very low binding affinity, while elongation of the non-coordinated, usually hydrophobic part of the inhibitor molecule may significantly enhance the interaction, indicating an essential role of the protein moiety in the azole-CYP51 complex formation (Ortiz de Montellano and Correia, 1995).

FIGURE 4.5.

Specific details of inhibitor-CYP51 complexes. (A) Surface binding subsite in posaconazole-bound T. cruzi CYP51 (surface representation, I-helix is shown). (B) The carboxamide fragment of VNI forms a hydrogen-bond network with T. brucei CYP51 helices B′ and I. The haem is shown as spheres. (C) VNF binds in the orientation opposite to VNI, its long arm being directed deeper into the active site cavity.

Interaction with posaconazole in T. cruzi CYP51 is strengthened by van der Waals contacts with 25 amino acid residues (Lepesheva et al., 2010a). Thirteen of these residues lie inside the substrate binding cavity, and 12 others are located around the entrance into the substrate access channel, surrounding the remote portion of the posaconazole long arm, which protrudes ~3 Å above the protein surface (Fig. 4.5A). This second binding subsite seems to be unique to the posaconazole-CYP51 interaction, its importance for the drug inhibitory potency being supported by the fact that posaconazole has much stronger anti-parasitic activity than its numerous derivatives of altered arm configuration (the side products of the posaconazole synthesis procedure) (Nomeir et al., 2008). Roughly, 25 van der Waals contacts should contribute up to 7.5 kcal/mol to the energy of the inhibitor–enzyme interaction.

In the complex with T. brucei CYP51 (Lepesheva et al., 2010b), VNI is oriented very similarly to posaconazole; however, its arm, being ~8 Å shorter, does not reach the protein surface. Although van der Waals contacts are formed with only 15 protein residues (up to 4.5 kcal/mol), the carboxamide group of VNI provides two hydrogen bonds, which connect the inhibitor molecule with two secondary structural elements of the protein, helices B′ and I (Fig. 4.5B). Such a hydrogen-bond network should add up to 10 kcal/mol to the energy of the inhibitor/enzyme binding. Stronger anti-parasitic effect of VNI compared to posaconazole in T. cruzi (unpublished) is in agreement with these calculations.

VNF, which is structurally similar to VNI, binds to T. cruzi CYP51 in an opposite orientation (Fig. 4.5C), including 180° rotation of its carboxamide group fragment. Although the electron density for the hydrogen-bond network around VNF cannot be clearly seen at medium resolution, it is quite likely that the comparably strong inhibitory potencies of VNI and VNF can have the same “hydrogen-bond mediated” origin (Lepesheva et al., 2010a). The number of van der Waals contact forming residues in the VNF-CYP51 complex is 14. The longer, two-ring arm of VNF is intercalated between helices B′, C and the N-terminal portion of helix I, which are shifted 1–2 Å away from the haem compared to their position in the posaconazole and VNI-bound structures. The backbone rearrangements can cause some tension pushing the inhibitor back towards the haem plane and also strengthening the interaction.

Structure-directed modifications of the VNI/VNF scaffold are currently in progress, aiming to further enhance the compounds anti-parasitic potency and optimize their pharmacokinetic properties while maintaining their low potential for toxicity.

4.6.4. Towards drug selectivity

Because humans can consume cholesterol from the diet and statins, inhibitors of an early step of sterol biosynthesis (Fig. 4.1), are broadly used as cholesterol-lowering drugs; at first glance, blocking this pathway with anti-microbial azoles does not seem to be essential for humans. However, inhibitors selective for pathogenic sterol 14α-demethylases are still highly desirable, especially in cases of long-term systemic treatment, to prevent formation of harmful methylated sterols in the human body and also to avoid potentially negative effects on biosynthesis of meiosis activating sterols, steroid hormones and bile acids.

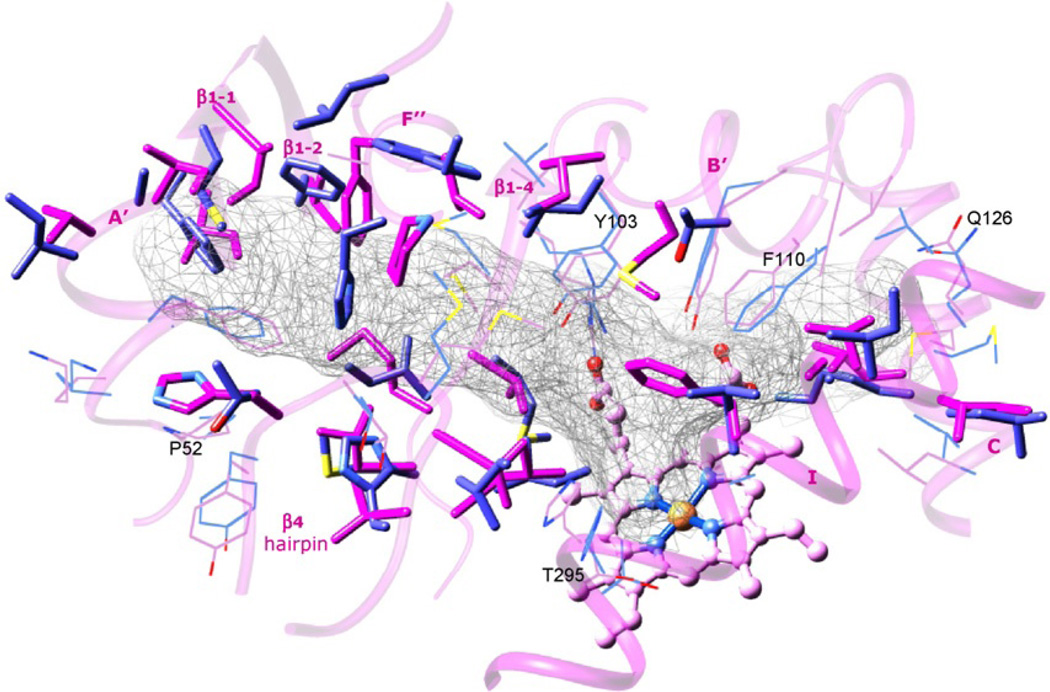

As mentioned above, when superimposed, the secondary structural elements which form the active site cavity in T. cruzi and human CYP51 have similar location. Very similar positions are occupied by several residues that are identical in all known CYP51 family members, allowing these enzymes to preserve their catalytic role across the kingdoms. However, 22 of the 47 cavity forming residues in T. cruzi CYP51 are different from the corresponding residues in the human counterpart (Fig. 4.6). These differences influence active site topology and can direct subtle structure-based modifications of CYP51 inhibitors in order to rationally increase their selectivity against human pathogens as well as to control potential development of CYP51-related resistance.

FIGURE 4.6.

Active site forming residues in T. cruzi (black) and human (grey) CYP51s. The corresponding secondary structural elements in T. cruzi are depicted as the transparent ribbon and marked, the haem is seen as ball and stick model. The active site cavity is outlined as grey mesh. The cavity residues which are conserved the human and T. cruzi enzymes are shown in line representation. Some of the residues conserved in the whole CYP51 family are marked (T. cruzi CYP51 numbering). The active site residues that differ in the two proteins are displayed as stick models.

4.7. ANTI-PARASITIC EFFECTS OF CYP51 INHIBITION IN TRYPANOSOMA CRUZI

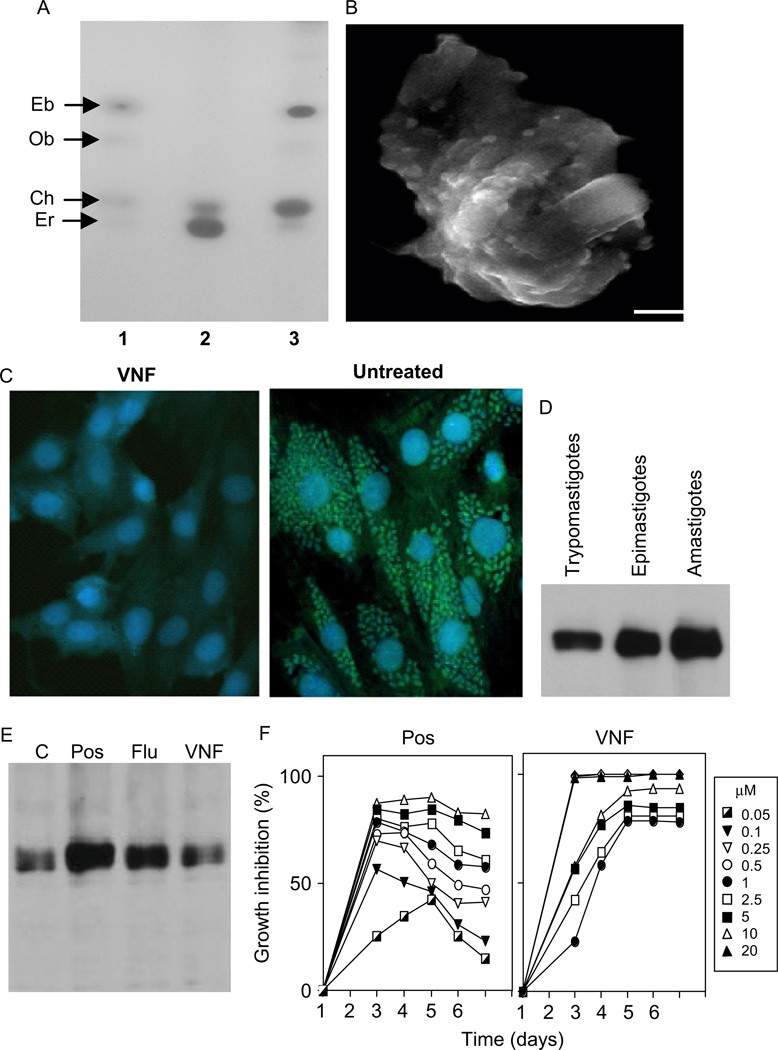

CYP51 inhibitors clearly affect T. cruzi sterol composition (Konkle et al., 2009; Lepesheva et al., 2007; Fig. 4.7A), profoundly damage ultrastructural organization of the parasite membranes (Lepesheva et al., 2008; Fig. 4.7B) and finally kill the pathogen, acting even stronger on its intracellular forms, amastigotes (Lepesheva et al., 2007; Fig. 4.7C). This is in good agreement with the results from the Urbina group (Liendo et al., 1998, 1999; Urbina et al., 1998, 2003a), the first to report that the anti-parasitic effects of anti-fungal azoles are usually much more expressed in the multiplying form of T. cruzi. Interestingly, we have found that the CYP51 gene, being expressed in significant amounts at all stages of the T. cruzi life-cycle is also upregulated in the multiplying forms of the parasite (Fig. 4.7.D). Altogether, this (1) confirms the importance of sterol biosynthesis to survival of T. cruzi, (2) reflects acceleration of the sterol flow in the multiplying stages of the pathogen, and (3) supports the notion (Lepesheva et al., 2010b) of possible requirements for additional sterol production, both structural and regulatory, which appear to be accelerated upon T. cruzi multiplication.

FIGURE 4.7.

Cellular effects of VNI/VNF in T. cruzi. (A) TLC of sterol standards (1) and unsaponified lipids extracted from T. cruzi amastigotes, untreated (2) and treated with 1 µM VNI (3). Eb, eburicol; Ob, obtusifoliol; Ch, cholesterol (exogenous); Er, ergosterol. (B) Scanning electron microscopy of T. cruzi amastigotes treated with 1 µM VNI; bar = I µm. Membrane disruption is seen as blebs on the surface. (C) Anti-parasitic effect of VNF (1 µM) on T. cruzi amastigotes within cardiomyocytes (GFP-expressing transgenic T. cruzi) is seen as small light dots, cardiomyocytes nuclei are seen as circles. (D) CYP51 gene expression in T. cruzi, immunoblotting. (E) CYP51 gene expression upon treatment of T. cruzi with 1 µM CYP51 inhibitors. C, control. (F) Inhibition of T. cruzi growth with different concentrations of posaconazole and VNF.

Finally, we have found that while posaconazole and fluconazole upregulate CYP51 gene expression in T. cruzi, our new carboxamide-containing inhibitory scaffold does not change it (Fig. 4.7E). Besides, contrary to posaconazole, it does not require increase in the concentration in order to maintain the inhibitory effect over time (Fig. 4.7F), which makes this scaffold highly advantageous in terms of its lower potential to cause resistance. Our most recent work has shown that at low drug concentration the anti-parasitic effect of VNI in T. cruzi is stronger than that of posaconazole (EC50 = 1.2 nM vs. ~5 nM, respectively (unpublished)). Testing of these compounds in animal models of Chagas disease as well as investigation of their pharmacokinetic properties is currently underway with the hope to bring new effective drugs for the chronic phase of the infection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful for support by the National Institute of Health grants GM067871 (M. R. W. and G. I. L.) and AI 080580 (F. V) and Vanderbilt Institute of Chemical Biology Pilot Project grant 2011 (G. I. L.).

REFERENCES

- Aoyama Y, Yoshida Y, Sonoda Y, Sato Y. 7-Oxo-24,25-dihydrolanosterol: a novel lanosterol 14 alpha-demethylase (P-45014DM) inhibitor which blocks electron transfer to the oxyferro intermediate. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1987;922:270–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apt W, Aguilera X, Arribada A, Perez C, Miranda C, Sanchez G, et al. Treatment of chronic Chagas’ disease with itraconazole and allopurinol. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1998;59:133–138. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo MS, Martins-Filho OA, Pereira ME, Brener Z. A combination of benznidazole and ketoconazole enhances efficacy of chemotherapy of experimental Chagas’ disease. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2000;45:819–824. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.6.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach DH, Goad LJ, Holz GG., Jr Effects of ketoconazole on sterol biosynthesis by Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1986;136:851–856. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)90410-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste P. Sterol biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1986;37:275–308. [Google Scholar]

- Bossard MJ, Tomaszek TA, Gallagher TF, Metcalf BW, Adams JL. Steroidal acetylenes—mechanism-based inactivators of lanosterol 14-alpha-demethylase. Bioorg. Chem. 1991;19:418–432. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner F, Yokoyama K, Lockman J, Aikenhead K, Ohkanda J, Sadilek M, et al. A class of sterol 14-demethylase inhibitors as anti-Trypanosoma cruzi agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:15149–15153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2535442100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammerer SB, Jimenez C, Jones S, Gros L, Lorente SO, Rodrigues C, et al. Quinuclidine derivatives as potential antiparasitics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:4049–4061. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00205-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CK, Doyle PS, Yermalitskaya LV, Mackey ZB, Ang KK, McKerrow JH, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi CYP51 inhibitor derived from a Mycobacterium tuberculosis screen hit. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009;3:e372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AC, Coleman RG, Smyth KT, Cao Q, Soulard P, Caffrey DR, et al. Structure-based maximal affinity model predicts small-molecule druggability. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:71–75. doi: 10.1038/nbt1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton J. Chagas disease: pushing through the pipeline. Nature. 2010;465:S12–S15. doi: 10.1038/nature09224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AB, Wright JJ, Ganguly AK, Desai J, Loebenberg D, Parmegiani R, et al. Synthesis and anti-fungal properties of 14-aminomethyl-substituted lanosterol derivatives. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1988;544:109–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb40394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cournia Z, Ullmann GM, Smith JC. Differential effects of cholesterol, ergosterol and lanosterol on a dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine membrane: a molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:1786–1801. doi: 10.1021/jp065172i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz Lde F, Caldas IS, Guedes PM, Crepalde G, de Lana M, Carneiro CM, et al. Effects of ravuconazole treatment on parasite load and immune response in dogs experimentally infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:2979–2986. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01742-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docampo R, Moreno SN, Turrens JF, Katzin AM, Gonzalez-Cappa SM, Stoppani AO. Biochemical and ultrastructural alterations produced by miconazole and econazole in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1981;3:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(81)90047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle PS, Chen CK, Johnston JB, Hopkins SD, Leung SS, Jacobson MP, et al. A nonazole CYP51 inhibitor cures Chagas’ disease in a mouse model of acute infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:2480–2488. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00281-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye LL, Cusack KP, Leonard DA. 32-Methyl-32-oxylanosterols: dual-action inhibitors of cholesterol biosynthesis. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36:410–416. doi: 10.1021/jm00055a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature. 1990;343:425–430. doi: 10.1038/343425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros L, Castillo-Acosta VM, Jimenez Jimenez C, Sealey-Cardona M, Vargas S, Manuel Estevez A, et al. New azasterols against Trypanosoma brucei: role of 24-sterol methyltransferase in inhibitor action. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2595–2601. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01508-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines TH. Do sterols reduce proton and sodium leaks through lipid bilayers? Prog. Lipid Res. 2001;40:299–324. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(01)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughan PA, Goad LJ. Coombs G, North M. Biochemical Protozoology. London: Taylor & Francis; 1991. Lipid biochemistry of trypanosomatids; pp. 312–328. [Google Scholar]

- Hucke O, Gelb MH, Verlinde CL, Buckner FS. The protein farnesyltransferase inhibitor Tipifarnib as a new lead for the development of drugs against Chagas disease. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:5415–5418. doi: 10.1021/jm050441z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh KL, Guo K, Dunford JE, Wu X, Knapp S, Ebetino FH, et al. The molecular mechanism of nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates as anti-osteoporosis drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:7829–7834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601643103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkle ME, Hargrove TY, Kleshchenko YY, von Kries JP, Ridenour W, Uddin MJ, et al. Indomethacin amides as a novel molecular scaffold for targeting Trypanosoma cruzi sterol 14 alpha-demethylase. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:2846–2853. doi: 10.1021/jm801643b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus JM, Verlinde CL, Karimi M, Lepesheva GI, Gelb MH, Buckner FS. Rational modification of a candidate cancer drug for use against Chagas disease. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:1639–1647. doi: 10.1021/jm801313t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepesheva GI, Waterman MR. Sterol 14alpha-demethylase cytochrome P450 (CYP51), a P450 in all biological kingdoms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1770:467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepesheva GI, Waterman MR. Structural basis for conservation in the CYP51 family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1814:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepesheva GI, Virus C, Waterman MR. Conservation in the CYP51 family. Role of the B’ helix/BC loop and helices F and G in enzymatic function. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9091–9101. doi: 10.1021/bi034663f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepesheva GI, Hargrove TY, Ott RD, Nes WD, Waterman MR. Biodiversity of CYP51 in trypanosomes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006a;34:1161–1164. doi: 10.1042/BST0341161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepesheva GI, Zaitseva NG, Nes WD, Zhou W, Arase M, Liu J et al. CYP51 from Trypanosoma cruzi: a phyla-specific residue in the B’ helix defines substrate preferences of sterol 14alpha-demethylase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006b;281:3577–3585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepesheva GI, Ott RD, Hargrove TY, Kleshchenko YY, Schuster I, Nes WD, et al. Sterol 14 alpha-demethylase as a potential target for anti-trypanosomal therapy: enzyme inhibition and parasite cell growth. Chem. Biol. 2007;14:1283–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepesheva G, Hargrove T, Kleshchenko Y, Nes W, Villalta F, Waterman M. CYP51: a major drug target in the cytochrome P450 superfamily. Lipids. 2008;43:1117–1125. doi: 10.1007/s11745-008-3225-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepesheva GI, Hargrove TY, Anderson S, Kleshchenko Y, Furtak V, Wawrzak Z, et al. Structural insights into inhibition of sterol 14 alpha-demethylase in the human pathogen Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Biol. Chem. 2010a;285:25582–25590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.133215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepesheva GI, Park HW, Hargrove TY, Vanhollebeke B, Wawrzak Z, Harp JM, et al. Crystal structures of Trypanosoma brucei sterol 14 alpha-demethylase and implications for selective treatment of human infections. J. Biol. Chem. 2010b;285:1773–1780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.067470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liendo A, Lazardi K, Urbina JA. In-vitro anti-proliferative effects and mechanism of action of the bis-triazole D0870 and its S(—) enantiomer against Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1998;41:197–205. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liendo A, Visbal G, Piras MM, Piras R, Urbina JA. Sterol composition and biosynthesis in Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1999;104:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaraci F, Jimenez CJ, Rodrigues C, Rodrigues JC, Braga MV, Yardley V, et al. Azasterols as inhibitors of sterol 24-methyltransferase in Leishmania species and Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:4714–4727. doi: 10.1021/jm021114j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina J, Martins-Filho O, Brener Z, Romanha AJ, Loebenberg D, Urbina JA. Activities of the triazole derivative SCH56592 (posaconazole) against drug-resistant strains of the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed murine hosts. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000;44:150–155. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.1.150-155.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagappan V, Deresinski S. Reviews of anti-infective agents: posaconazole: a broad-spectrum triazole anti-fungal agent. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007;45:1610–1617. doi: 10.1086/523576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nes WR. Role of sterols in membranes. Lipids. 1974;9:596–612. doi: 10.1007/BF02532509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomeir AA, Pramanik BN, Heimark L, Bennett F, Veals J, Bartner P, et al. Posaconazole (Noxafil, SCH 56592), a new azole anti-fungal drug, was a discovery based on the isolation and mass spectral characterization of a circulating metabolite of an earlier lead (SCH 51048) J. Mass Spectrom. 2008;43:509–517. doi: 10.1002/jms.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obach RS, Walsky RL, Venkatakrishnan K, Gaman EA, Houston JB, Tremaine LM. The utility of in vitro cytochrome P450 inhibition data in the prediction of drug-drug interactions. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 2006;316:336–348. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.093229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura T, Sato R. The carbon monoxide-binding pigment of liver microsomes. I. Evidence for its hemoprotein nature. J. Biol. Chem. 1964;239:2370–2378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz de Montellano PR, Correia MA. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes. In: Ortiz de Montellano PR, editor. Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry. New York: Plenum Publishing Corporation; 1995. pp. 305–364. [Google Scholar]

- Pena-Diaz J, Montalvetti A, Flores CL, Constan A, Hurtado-Guerrero R, De Souza W, et al. Mitochondrial localization of the mevalonate pathway enzyme 3-Hydroxy-3- methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase in the Trypanosomatidae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:1356–1363. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-10-0720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrikkos G, Skiada A. Recent advances in anti-fungal chemotherapy. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2007;30:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinazo MJ, Espinosa G, Gallego M, Lopez-Chejade PL, Urbina JA, Gascon J. Successful treatment with posaconazole of a patient with chronic Chagas disease and systemic lupus erythematosus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010;82:583–587. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulos TL, Finzel BC, Howard AJ. High-resolution crystal-structure of cytochrome-P450cam. J. Mol. Biol. 1987;195:687–700. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puccetti L, Acampa M, Auteri A. Pharmacogenetics of statins therapy. Recent Pat. Cardiovasc. Drug Discov. 2007;2:228–236. doi: 10.2174/157489007782418982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinones W, Urbina JA, Dubourdieu M, Luis Concepcion J. The glycosome membrane of Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes: protein and lipid composition. Exp. Parasitol. 2004;106:135–149. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues CO, Catisti R, Uyemura SA, Vercesi AE, Lira R, Rodriguez C, et al. The sterol composition of Trypanosoma cruzi changes after growth in different culture media and results in different sensitivity to digitonin-permeabilization. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2001;48:588–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2001.tb00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohmer M, Bouvier P, Ourisson G. Molecular evolution of biomembranes: structural equivalents and phylogenetic precursors of sterols. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:847–851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.2.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller H. The role of sterols in plant growth and development. Prog. Lipid Res. 2003;42:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(02)00047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller DS, Fung HB. Posaconazole: an extended-spectrum triazole anti-fungal agent. Clin. Ther. 2007;29:1862–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroepfer GJ., Jr Sterol biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1981;50:585–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzaskos JM, Ko SS, Magolda RL, Favata MF, Fischer RT, Stam SH, et al. Substrate-based inhibitors of lanosterol 14 alpha-methyl demethylase: I. Assessment of inhibitor structure-activity relationship and cholesterol biosynthesis inhibition properties. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9670–9676. doi: 10.1021/bi00030a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuck SF, Patel H, Safi E, Robinson CH. Lanosterol 14 alpha-demethylase (P45014DM): effects of P45014DM inhibitors on sterol biosynthesis downstream of lanosterol. J. Lipid Res. 1991;32:893–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina JA. Ergosterol biosynthesis and drug development for Chagas disease. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(Suppl. 1):311–318. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000900041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina JA. New insights in Chagas’ disease treatment. Drugs Future. 2010;35:409–419. [Google Scholar]

- Urbina JA, Lazardi K, Aguirre T, Piras MM, Piras R. Anti-proliferative synergism of the allylamine SF 86-327 and ketoconazole on epimastigotes and amastigotes of Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1237–1242. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.8.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina JA, Payares G, Molina J, Sanoja C, Liendo A, Lazardi K, et al. Cure of short- and long-term experimental Chagas’ disease using D0870. Science. 1996;273:969–971. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina JA, Payares G, Contreras LM, Liendo A, Sanoja C, Molina J, et al. Anti-proliferative effects and mechanism of action of SCH 56592 against Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi: in vitro and in vivo studies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1771–1777. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina JA, Lira R, Visbal G, Bartroli J. In vitro anti-proliferative effects and mechanism of action of the new triazole derivative UR-9825 against the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2498–2502. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.9.2498-2502.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina JA, Payares G, Sanoja C, Lira R, Romanha AJ. In vitro and in vivo activities of ravuconazole on Trypanosoma cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas disease. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2003a;21:27–38. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00273-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina JA, Payares G, Sanoja C, Molina J, Lira R, Brener Z, et al. Parasitological cure of acute and chronic experimental Chagas disease using the long-acting experimental triazole TAK-187. Activity against drug-resistant Trypanosoma cruzi strains. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2003b;21:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkman JK. Sterols and other triterpenoids: source specificity and evolution of biosynthetic pathways. Org. Geochem. 2005;36:139–159. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler D, Courtney R, Richards W, Banfield C, Lim J, Laughlin M. Effect of posaconazole on cytochrome P450 enzymes: a randomized, open-label, two-way crossover study. Euro. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2004;21:645–653. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeagle PL, Martin RB, Lala AK, Lin HK, Bloch K. Differential effects of cholesterol and lanosterol on artificial membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1977;74:4924–4926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.11.4924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Aoyama Y, Noshiro M, Gotoh O. Sterol 14-demethylase P450 (CYP51) provides a breakthrough for the discussion on the evolution of cytochrome P450 gene superfamily. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;273:799–804. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonios DI, Bennett JE. Update on azole anti-fungals. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008;29:198–210. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1063858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]