Abstract

Along with its natriuretic, diuretic, and vasodilatory properties, atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and its guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-A (GC-A/NPRA) exhibit an inhibitory effect on cell growth and proliferation. However, the signaling pathways mediating this inhibition are not well understood. The objective of this study was to determine the effect of ANP-NPRA system on mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and the downstream proliferative transcription factors involving activating protein-1 (AP-1) and cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB) in agonist-stimulated mouse mesangial cells (MMCs). We found that ANP inhibited vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-stimulated phosphorylation of MAPKs (Erk1, Erk2, JNK, and p38), to a greater extent in NPRA-transfected cells (50–60%) relative to vector-transfected cells (25–30%). The analyses of the phosphorylated transcription factors revealed that ANP inhibited VEGF-stimulated activation of CREB, and the AP-1 subunits (c-jun and c-fos). Gel shift assays demonstrated that ANP inhibited VEGF-stimulated AP-1 and CREB DNA-binding ability by 67 % and 62 %, respectively. The addition of the protein kinase G (PKG) inhibitor, KT-5823, restored the VEGF-stimulated activation of MAPKs, AP-1, and CREB, demonstrating the integral role of cGMP/PKG signaling in NPRA-mediated effects. Our results delineate the under lying mechanisms through which ANP-NPRA system exerts an inhibitory effect on MAPKs and down-stream effector molecules, AP-1 and CREB, critical for cell growth and proliferation.

Keywords: Atrial natriuretic peptide, guanylyl cyclase receptor, vascular endothelial growth factor, phosphorylation, mesangial cells

Introduction

Cardiac hormone atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) exerts profound effects on cardiovascular system by regulating sodium excretion, water balance, and vasodilation [1–5]. In addition, ANP has been proven to potently inhibit cell growth and proliferation under both physiological and pathophysiological conditions, such as cardiac hypertrophy and the metastasis of cancer cells [5–7]. ANP belongs to the natriuretic peptide family comprised of three peptide hormones: ANP, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), and C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) and all three hormones are encoded by separate gene [8]. These peptide hormones exert their biological effects by binding members of the natriuretic peptide receptor (NPR) family. Three subtypes of natriuretic peptide receptors have been identified; two contain intrinsic guanylyl cyclase activity and are known as guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-A (GC-A/NPRA) and guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-B (GC-B/NPRB) [5, 6, 9]. A third receptor subtype, which contains a truncated cytoplasmic domain and lacks guanylyl cyclase activity, has been termed as natriuretic peptide clearance receptor (NPRC). Both ANP and BNP stimulate NPRA whereas CNP activates NPRB, and all three natriuretic peptides bind to NPRC. NPRA is considered the principal receptor for ANP since the major physiological responses to ANP in the cardiovascular system are mimicked by cGMP and its cell permeable analogs [5, 10, 11].

Upon binding of ANP to NPRA and dimerization of the receptor, a conformational change activates the guanylyl cyclase domain of the receptor [12, 13], and the resulting elevation of intracellular cGMP levels activates cGMP dependent protein kinase (PKG). The ANP-NPRA-cGMP cascade is believed to produce cellular and physiological responses by interacting with PKG, cGMP-gated ion channels, and cGMP-regulated cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases [14]. However, the signaling molecules downstream of PKG that are responsible for inhibition of cell proliferation have not been fully identified. Stimulation of cell proliferation involves a complex cascade of intracellular signaling processes, a central component of which is the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs). These serine/threonine kinases play a critical role in regulation of biological response mechanisms through phosphorylation of various targets, including mitochondrial proteins, cytoplasmic proteins, and transcription factors [15, 16]. In the current study, we investigated the signaling pathways through which ANP inhibits cell proliferation in cultured mouse mesangial cells (MMCs). The findings reveal that ANP/NPRA system negatively regulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-induced MAPKs and the downstream proliferative transcription factors AP-1 (activating protein-1) and CREB (cAMP-response element binding protein) and that this effect requires cGMP-dependent protein kinase.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The pCRE-Luc, pAP1-Luc, and pRL-TK vectors were purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). VEGF was obtained from Millipore (Bellerica, MA). Oligionucleoties for electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) were purchased from MWG Biotech (Huntsville, AL). Cell culture media, fetal calf serum, ITS (insulin, transferring, and sodium selenite), and Lipofectamine-2000 were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). 4-,2-hydroxyethyl-1-piperazineethanesulfonic (HEPES), MAPKs inhibitors (U0126, SP600125, and SB203580), PKG inhibitor KT-5823, and VEGF receptor inhibitor were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). The Light Shift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit was purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Aprotinin, leupeptin, phenylmethylsulfonyl flouride (PMSF) and β-actin were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO); all other antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). All other reagents utilized were molecular biology reagent grade.

Cell culture, electroporation, and hormone treatment

Studies were performed using MMCs isolated from mouse glomeruli and cultured in Dubecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing ITS and 10% fetal bovine serum as previously described [17]. Cells were used between the fourth and fourteenth passages and cultures were maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2/ 95% O2. For NPRA-overexpression experiments, MMCs were transiently transfected with recombinant NPRA cDNA [13] using electroporation at 220 mV with a capacitance setting of 960 µF. Cells were then synchronized by serum starvation by incubating in serum-free medium containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 24 h. For hormonal treatment, cells were pretreated with 0.2 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methyl xanthin (IBMX), followed by treatment with VEGF in the presence or absence of ANP. The reproducibility of transfection efficiency were examined using the beta-x-galactosidase (β-x-gal) staining kit (Stratagene, LA Jolla, CA). In the present experiments using electroporation, approximately 70–75% transiently transfected cells were able to harbor recombinant NPRA cDNA molecules.

Cell proliferation assays

Native MMCs and MMCs overexpressing NPRA were treated with VEGF for 24 h in the presence or absence of ANP. Cell proliferation in response to hormonal treatment was measured by cell counting. Hormone-treated and control cells were washed, trypsinized, and counted using a hemocytometer.

Western blot analysis

For whole cell extract preparation, hormone-treated and control cells were washed and extracts prepared according to previously established methods [18, 19]. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The extract was homogenized and the clear cell lysate collected and stored at −70 °C until use. The protein concentration of the lysate was determined using Bradford protein assay reagent from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). For electrophoresis, whole cell lysate (50 µg protein) was mixed with sample loading buffer, boiled, and resolved by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate -polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE). Proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane, which was then blocked with 5% fat-free milk solution in 1× Tris - buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBST) for 2 h at room temperature. The membrane was incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C in blocking solution and treated with the secondary horse radish peroxide are (HRP) -conjugated antibody for 2 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (CECL) plus detection system from Alpha-Innotech and the density of the protein bands were determined using the Alpha Innotech Imaging System (San Leandro, CA).

Cell transfection and luciferase assay

Cells were seeded in 24-well plates and grown to 70–80% confluence in complete medium. Cells were transiently transfected with 1 µg of response element-luciferase construct plasmids and cotransfected with 300 ng of pRL-TK expression construct (as an internal transfection efficiency control) using Lipofectamine reagent from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and maintained in serum-free medium with 0.1% BSA for 24 h. Transfected cells were then treated with stimulating growth factors and ANP. Cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times and harvested in passive lysis buffer provided with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit from Promega (Madison, WI). The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 3 min at 4°C. The cleared supernatant was used for luciferase activity assay using a Floustar Optima Microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Durham, NC). Results were normalized for transfection efficiency as relative to light units per Renilla luciferase activity.

Nuclear extract preparation

Hormonal treatment was carried out in synchronized MMCs in serum-free medium containing 0.1% BSA. Cells were then rinsed twice with PBS, scraped, and nuclear extracts prepared by previously-established methods [20]. Harvested cells were centrifuged at 2,100 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the cell pellet washed with PBS and resuspended in five volumes of buffer A (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10 µg/ml aprotinin, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, 0.5 mM PMSF). After 10 min incubation on ice, extracts were centrifuged as above and resuspended in three volumes of buffer A with 0.05% Nonidet P-40. The extracts were then homogenized by 20 strokes of a Dounce homogenizer and centrifuged at 2100 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and stored as the cytoplasmic extract, whereas the pellet (nuclear extract) was resuspended in 100 µl of buffer C (5 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 26% glycerol, 300 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 10 µg/ml aprotinin, 10 µg/ml leupeptin). The resuspension was incubated on ice for 30 min and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined and the extracts were stored at −70°C.

Electrophoretic mobility shift and antibody supershift assays

Protein–DNA complexes were detected using 5′ biotin end-labeled double-stranded DNA probes prepared by annealing complementary oligonucleotides matching transcription elements. The forward sequences for the AP-1- and CREB-binding oligonucleotides were 5'-cgcttgatgactcagccggaa-3' and 5'-agagattgcctgacgtcagagagctag-3', respectively (binding sites underlined). The forward sequences for the mutant AP-1- and CREB-binding oligonucleotides were 5'-cgcttgatgacttggccggaa-3' and 5'-agagattgcctgtggtcagagagctag-3', respectively (mutant nucleotides underlined). The binding reaction was performed using Light Shift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit. Nuclear extract (2 µg protein) and binding buffer were incubated for 5 min on ice. After addition of biotin-labeled probe, the reaction mixture was incubated for an additional 25 min at room temperature. For supershift experiments, the extracts were pre-incubated for 60 min on ice with c-jun, c-fos, or CREB-1 antibody. The protein–DNA complex was resolved on non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel and observed according to the manufacture's protocol, as previously described [21].

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as mean ± standard error of the average responses in multiple experiments performed with different cell preparations. Results were normalized relative to untreated control. Statistical significance was assessed using ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons post hoc test. The probability value of p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

ANP Treatment inhibits mesangial cell proliferation

The results presented in Fig. 1 show that VEGF treatment stimulated MMC proliferation in both vector-transfected and NPRA-transfected cells by 3.5-fold relative to untreated cells. ANP treatment inhibited the proliferation of un-stimulated and VEGF-stimulated vector-transfected cells by 13% and 28% respectively, while this inhibition was significantly more pronounced in NPRA-transfected cells (20% inhibition in un-stimulated and 42% in VEGF-stimulated cells). Interestingly, the activation of proliferation by VEGF was similar in both cell culture models.

Figure 1. Effect of ANP treatment on cell proliferation of VEGF-stimulated in vector-transfected (A) and NPRA-transfected (B) MMCs.

MMCs were seeded at 100,000 cells and incubated with VEGF (20 ng/ml), ANP, or both VEGF and ANP at the indicated concentrations, preceded by incubation with KT-5823 (10 µM) or VEGF receptor inhibitor (VRI; 10 µM). Cells were trypsinized and counted after 24 h. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, relative to VEGF treatment. Bars represent the mean ± S.E. of four independent experiments.

Overexpression NPRA markedly inhibits VEGF-stimulated MAPKs phosphorylation

Since MAPKs are essential mediators of cell proliferation, we assessed the effect of ANP/NPRA system on VEGF-stimulated MAPKs (Erk1, Erk2, p38, and JNK) using Western blot analysis. ANP caused a dose-dependent inhibition of VEGF-stimulated Erk1 and Erk2 phosphorylation (Fig. 2 A and B). This effect was more pronounced in NPRA-transfected MMCs than in vector-transfected MMCs, with maximal inhibition of 65%. Similarly, VEGF treatment stimulated p38 and JNK phosphorylation by approximately 3- to 4- fold in both vector- and NPRA-transfected cells (Fig. 3 A–D). ANP co-treatment inhibited VEGF-stimulated p38 and JNK phosphorylation by 20–25% in vector-transfected cells (Fig. 3 A and C, lane 4) and by 55–60% in NPRA-transfected cells (Fig. 3 B and D, lane 4). ANP treatment inhibited MAPK phosphorylation in un-stimulated cells (by 20% in vector-transfected MMCs and 30% in NPRA-transfected MMCs), though to a lesser extent than in VEGF-stimulated cells. To determine the role that cGMP and PKG play in mediating the inhibition of MAPKs by ANP, we pretreated the cells with the PKG inhibitor KT-5823 (Fig. 4 A–D). In MMCs, treated with both ANP and VEGF, the PKG inhibitor KT-5823 restored MAPKs activation to levels in cells treated with VEGF alone (Fig. 4 A and B, lanes 2 vs. 4), an effect that was observed to a lesser extent in vector-transfected (Fig. 4 A and C) and more pronounced in NPRA-transfected (Fig. 4 B and D) cells.

Figure 2. Effect of ANP treatment on phosphorylation of Erk 1/2 in vector-tranfected (A) and NPRA-transfected (B) MMCs.

Cells treated with 20 ng/ml VEGF in the presence or absence of 100 nM ANP were solubilized as described in the Materials and Methods section. Phosphorylated Erk1 and Erk2 levels were assessed by Western blot analysis. *p<0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001, relative to control. Beta-actin was used as an internal control. Blots are the representative of 4–5 experiments. The bars represent the mean ± S.E. of 4 independent experiments.

Figure 3. Effect of ANP treatment on phosphorylation of p38 and JNK in vector-tranfected (A,C) and NPRA-transfected (B,D) MMCs.

Cells treated with 20 ng/ml VEGF in the presence or absence of 100 nM ANP were solubilized as described in the Materials and Methods section. Phosphorylated p38 (A,B) and phosphorylated JNK (C,D) levels were assessed by Western blot analysis. *p<0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001, relative to control. Beta-actin was used as an internal control. Blots are the representative of 4 experiments and bars represent the mean ± S.E.

Figure 4. Role of PKG in inhibition of MAPK phosphorylation by ANP.

Phosphorylated MAPK levels were measured in vector-transfected (A,C) and NPRA-transfected (B,D) MMCs treated with 20 ng/ml VEGF, 100 nM ANP, and/or 10 µM KT-5823. VEGF receptor inhibitor (10 µM) was used as a control. Quantitative results were derived from multiple (n≥3) experiments. Beta-actin was used as an internal control. Blots are the representative of three experiments. and bars represent the mean ± S.E.

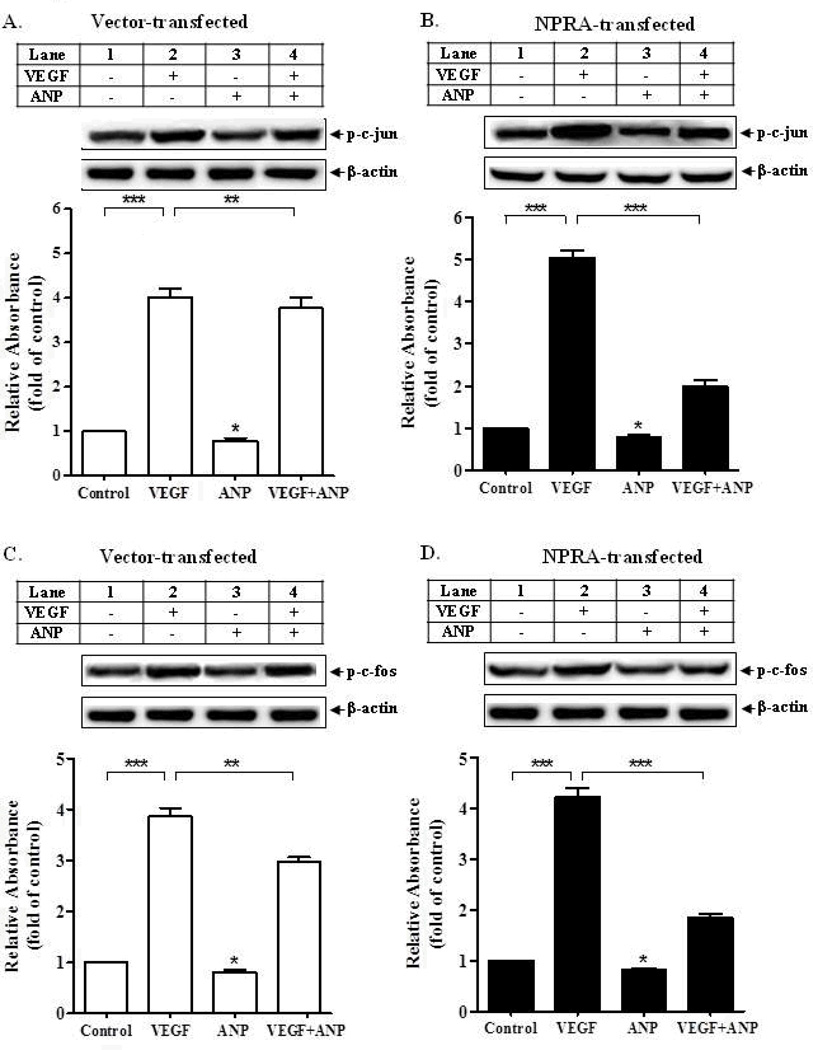

Expression of NPRA inhibits MAPK-dependent activation of AP-1 and CREB

MAPKs are known to phosphorylate and activate a number of cellular targets to stimulate proliferation, including transcription factors, AP-1 and CREB. To determine which downstream transcriptional molecules are involved in the inhibitory effects of ANP on cell proliferation, we measured the effect of ANP treatment on the phosphorylation, DNA-binding ability, and activity of two major proliferative transcription factors, AP-1 (comprised of c-jun and c-fos) and CREB. Western blot detection of phosphorylated c-jun and c-fos showed that VEGF treatment stimulated phosphorylation of c-jun by approximately 4- to 4.5 -fold (Fig. 5 A and B) and that of c-fos by approximately 4-fold (Fig. 5 C and D) in both vector- and NPRA-transfected MMCs, respectively. Similarly, VEGF also stimulated the phosphorylation of CREB by more than 5-fold in both vector-transfected and NPRA-transfected cells (Fig. 6 A and B). In the absence of VEGF, ANP treatment alone inhibited phosphorylation by 15–20% in vector-transfected cells and by 25–30% in NPRA-transfected cells. However, ANP treatment in conjunction with VEGF treatment, inhibited phosphorylation by 25–30% in vector-transfected cells and almost 60–65% in NPRA-transfected cells, relative to VEGF-stimulated cells (Fig. 5 A–D and Fig. 6 A and B).

Figure 5. Effect of ANP treatment on VEGF-stimulated phosphorylation of AP-1 (c-fos and c-jun) in MMCs.

Western blot analysis was performed to detect p-c-jun (A,B) and p-c-fos (C,D) levels in vector-transfected (A,C) and NPRA-transfected (B,D) MMCs treated with 20 ng/ml VEGF in the presence or absence of 100 nM ANP. *p<0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001, relative to control. Beta-actin was used as an internal control. Blots are the representative of 4 experiments. and bars represent the mean ± S.E.

Figure 6. Effect of ANP treatment on VEGF-stimulated phosphorylation of CREB.

Western blot analysis was performed to detect pCREB levels in vector-transfected (A) and NPRA-transfected (B) MMCs treated with 20 ng/ml VEGF in the presence or absence of 100 nM ANP. *p<0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001, relative to control. Beta-actin was used as an internal control. Blots are the representative of 5 experiments. and bars represent the mean ± S.E.

ANP/NPRA system inhibits AP-1- and CREB-dependent luciferase expression

In addition to phosphorylation, we assessed transcription factor activation using luciferase constructs driven by repeats of AP-1 or CRE cis elements. VEGF treatment activated AP-1-driven luciferase expression by 8-fold in both vector- and NPRA-transfected MMCs (Fig. 7 A and B, lanes 1 vs. 3). This stimulation was inhibited upon co-treatment with ANP, by 30% in vector-transfected cells and 67% in NPRA-transfected cells (lanes 3 vs. 4). VEGF and ANP treatment had similar effects on CREB-dependent luciferase expression (Fig. 7 C and D). VEGF treatment stimulated luciferase expression by 7-fold (lanes 1 vs. 3), and ANP treatment inhibited VEGF-stimulated expression by 26% in vector-transfected and 66% in NPRA-transfected cells (lanes 3 vs. 4). In each experiment, pretreatment of ANP-treated cells with PKG inhibitor, KT-5823, resulted in restoration of VEGF-stimulated activation of luciferase expression (lanes 5), confirming that the inhibitory effect of ANP on proliferative factors is PKG-dependent.

Figure 7. Effect of ANP treatment on VEGF-stimulated AP-1 and CREB transcriptional activity.

Transcriptional activation of AP-1 (A,B) and CREB (C,D) in response to ANP treatment was measured using AP-1- and CREB-driven luciferase constructs and dual luciferase assay. *p<0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001, relative to control. Bars represent the mean ± S.E. of 4 independent experiments.

ANP/NPRA system antagonizes the DNA-binding ability of AP-1 and CREB

The effects of VEGF and ANP on the DNA-binding ability of AP-1 and CREB were determined using EMSA (Fig. 8 A–D). The specificity of binding was confirmed using a mutant binding sequence (lane 4), unlabeled competitor (lane 5), and antibody supershift assay (lane 6, 7). VEGF treatment resulted in enhanced DNA-binding of AP1 (Fig. 8 A and B, lanes 1 vs. 2), an effect which was inhibited by ANP to a greater extent in NPRA-transfected cells than vector-transfected cells (lanes 2 vs. 3). The use of mutant probe and competitor oligonucleotides confirmed that the binding was specific, and the identity of the DNA-binding proteins was confirmed as c-fos and c-jun using supershift (Fig. 8 A and B). Similarly, VEGF enhanced the DNA-binding ability of CREB, and ANP treatment inhibited it to a great extent (Fig. 8 C and D).

Figure 8. Effect of ANP treatment on VEGF-stimulated DNA-binding activity of AP-1 and CREB.

In vitro DNA-binding ability of AP-1 (A,B) and CREB (C,D) in response to ANP treatment was assessed using a biotin-labeled electrophoretic mobility shift assay. Specificity of DNA-protein complex formation was confirmed using a mutant binding sequence (mut), unlabeled competitor (comp), and antibody supershift (Ab). P=free probe, J=c-jun antibody, F=c-fos antibody, C=CREB-1 antibody. Autoradiogram is the representative of 3 independent experiments and bars represent mean ± S.E.

We determined the role of specific MAPKs in the activation of AP-1 and CREB using the luciferase-reporter construct to quantify transcriptional activation in response to pretreatment with three MAPKs inhibitors (Figure 9). Treatment with the Erk1/2 inhibitor U0126 (10 µM) resulted in a significant inhibition of VEGF-stimulated AP-1 and CREB transcriptional activity (lane 4). Similarly, treatment with the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (10 µM), caused inhibition of transcriptional activity of both AP-1 and CREB (lane 5). However, treatment with the p38 inhibitor SB203580 (10 µM) had no significant effect on the activity of either transcription factor (lane 6).

Figure 9. Role of specific inhibitors of MAPKs in activation of AP-1 and CREB in MMCs.

Transcriptional activation of AP-1 (A) and CREB (B) in response to VEGF after pretreatment of cells with the inhibitors of Erk1/2 (U0128), JNK (SP00028), and p38 (SB0058) was measured using AP-1- and CREB-driven luciferase constructs and dual luciferase assay. Bars represent the mean ± S.E. of 4 independent experiments. ***p<0.001, relative to VEGF-treated cells.

Discussion

The results presented herein demonstrate that VEGF stimulates proliferation of MMCs by 3.5-fold, an effect that is significantly inhibited by ANP at dosages as low as 1 nM, proving the strong potential of ANP as an antimitogenic hormone. VEGF is a potent mitogenic and angiogenic growth factor, playing significant roles in both development and pathology, such as cancer, diabetic retinopathy, cardiovascular events, and rheumatoid arthritis [22–24]. As such, VEGF-stimulated cells are an excellent model to study the ability of ANP to inhibit agonist-stimulated cell proliferation, a condition common in pathophysiological states. VEGF, like numerous growth factors, is known to activate MAPK signaling pathways in various cell types, initiating cascades that lead to cell growth and proliferation, including stimulation of proto-oncogenes and early genes [22, 25–28]. Our experiments uncovered that VEGF treatment increased phosphorylation of the four major MAPKs tested: Erk1, Erk2, p38, and JNK. This activation was inhibited significantly (p<0.001) upon ANP treatment. This suggests one mechanism through which ANP inhibits cell proliferation – the inhibition of MAPKs as well as identifying a stage at which cross-talk between the ANP and VEGF signaling cascades can occur. In addition, the JNK and p38 have been suggested to elicite functions beyond that of activating proliferation, such as mediating responses to cell stresses and the extracellular environment [15, 16]. The fact that ANP inhibits these MAPKs, which provide possible mechanisms through which ANP may stimulate anti-inflammatory signals [7, 9, 29, 30].

Vascular and renal cells contain two sub-types of ANP receptors, NPRA and NPRC; however, the involvement of specific natriuretic peptide receptor in the mechanisms for antigrowth responses have not been fully resolved. The disruption of the Npr1 gene (coding for NPRA) in mice causes blood pressure elevation and exacerbation of renal and cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis, thus NPRA has been suggested as the principal physiological receptor of ANP for antigrowth and proliferation effects in target cells [5, 21, 31]. It has also been suggested that NPRC may play a role in the inhibition of cell growth caused by ANP [32]. Indeed, MMCs express both NPRA and NPRC; however, the relative contributions of NPRA and NPRC in mediating ANP’s inhibitory effects on cell growth and proliferation are still not well understood [33–37]. The present strategies provided a model of NPRA overexpression in MMCs and allowed us to identify the effects of ANP-NPRA on cell growth and MAPKs (Erk 1/2, p38, JNK) that were negatively mediated by NPRA/cGMP signaling. ANP has been shown to bind both NPRA and NPRC, however, cANP selectively activates NPRC without elevation of the intracellular accumulation of cGMP [38, 39]. Interestingly, cANP has also been reported to exert only a small antiproliferative effect, implicating that additional cGMP-independent mechanism may contribute to the antiproliferative effect of these natriuretic peptides [40]. Those previous studies, also examined the antiproliferative action of ANP involving zaprinast, and suggested that ANP exerts antifroliferative action partly by cGMP since zaprinast alone did not cause any proliferation. Recent studies have shown that in chronic cardiac hypertrophy, ANP levels are greatly increased and NPRA-cGMP effects to ANP drastically diminished resulting a unique cGMP-independent elevation of pathological Ca2+ levels [41]. Those previous findings also suggested that NPRA forms a complex with cation channels exerting a cGMP-independent signaling pathway. However, more studies are needed to support the cGMP-independent signaling pathway of ANP action in a tissue- and cell -specific manner.

While the studies from our laboratory and by others have suggested that ANP inhibits MAPKs (Erk 1/Erk 2 and p38) in various cell types [17, 19, 42, 43], specific downstream targets of MAPKs mediated by the ANP-NPRA pathway have not yet been clearly identified. MAPKs are known to activate a number of proliferative transcription factors, including CREB and AP-1; composed of c-jun and c-fos in response to various growth factors and vasoconstrictors [44–47]. We hypothesized that the inhibition of MAPKs and downstream transcription factors are the major effector molecules through which the ANP-NPRA system inhibits cell growth and proliferation. We determined the effects of ANP on two important downstream transcription factors, which are activated by MAPKs and that regulate transcription of proliferative genes, AP-1 (c-fos and c-jun) and CREB. Our results demonstrate that the phosphorylation, DNA-binding capability, and activity of these transcription factors were all enhanced by VEGF. On the other hand, ANP treatment significantly inhibited the activation of AP-1 and CREB, indicating that inhibition of cell proliferation by ANP-NPRA-cGMP can be mediated through the diminished responses of these transcription factors.

To further clarify the pathways responsible for the activation and inhibition of cell growth and proliferation in our MMC system, we assessed the distinct contributions of Erk1/2, JNK, and p38 to the activation of AP-1 and CREB using specific MAPKs inhibitors. Interestingly, we found that while inhibition of Erk1/2 and JNK caused inhibition of AP-1 and CREB activity, p38 inhibition had no significant effect of the activity of either transcription factor. These results suggest that Erk1/2 and JNK, but not p38, are involved in activating AP-1 and CREB in MMCs. Although the downstream targets of p38 have not been previously investigated in the MMC system, nevertheless studies in the lymphoma cells suggest that p38 can activate CREB [48–50]. Nevertheless, in these systems, CREB activation occurs through the p38 phosphorylation of intermediary protein kinases such as MAPKAP (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase-Activated Protein) and MSK (Mitogen- and Stress- Activated Protein Kinase) [51].

Overall, the results of all factors studied including; cell proliferation, MAPKs (Erk1/2, p38, JNK), AP-1, and CREB clearly show that while ANP inhibited these signaling cascades in both MMC models, the effects were dramatically greater in NPRA-transfected cells relative to vector-transfected cells. Furthermore, since PKG mediates the effects of NPRA-activated signals, we used the PKG inhibitor KT-5823 to determine whether the inhibitory effects of ANP-NPRA were dependent on PKG. It was observed that KT-5823 restored MAPKs, AP-1, and CREB activation to VEGF-stimulated levels, thus indicating that PKG is essential for ANP-NPRA's inhibition of cell growth and proliferation. Together, the present results demonstrate the role of NPRA as the mediator of growth-inhibitory signaling cascade involving MAPKs and downstream effector molecules AP-1 and CREB.

In conclusions, the present study demonstrates that ANP-NPRA signaling negatively regulates VEGF-stimulated cell proliferation, MAPKs phosphorylation, and AP-1 and CREB phosphorylation, their DNA-binding ability, and transcriptional activation in a cGMP-PKG-dependent manner. These findings help to advance our understanding of the molecular mechanisms through which ANP-NPRA system inhibits MAPKs cascade and cell proliferation.

Acknowledgements

Authors wish to thank Huong Nguyen and Gevoni Bolden for technical assistance and Mrs. Kamala Pandey for assistance in typing of this manuscript. Our special thanks are due to Dr. Bharat B. Aggarwal, Department of Experimental Therapeutics and Cytokine Research Laboratory at MD Anderson Cancer Center and Dr. Susan L. Hamilton, Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics at Baylor College of Medicine for providing their facilities during our displacement period due to Hurricane Katrina. This work was supported from the National Institutes of Health grant (HL57531).

Abbreviations used: The abbreviations used are:

- ANP

Atrial natriuretic peptide

- GC-A/NPRA

guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-A

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- AP-1

activating protein-1

- CREB

cAMP response element binding protein

- MAPKs

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MMCs

mouse mesangial cells

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- HEPES

N-(2-Hydroxyethyl) piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulfonic acid)

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methyl xanthin

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assays

- SDS–PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate -polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PVDF

polyvinylidene fluoride

- TBST

Tris-buffered saline-tween-20

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl flouride

References

- 1.de Bold AJ, Borenstein HB, Veress AT, Sonnenberg H. A rapid and potent natriuretic response to intravenous injection of atrial myocardial extract in rats. Life Sci. 1981;28:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner BM, Ballermann BJ, Gunning ME, Zeidel ML. Diverse biological actions of atrial natriuretic peptide. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:665–699. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.3.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Bold AJ. Atrial natriuretic factor: a hormone produced by the heart. Science. 1985;230:767–770. doi: 10.1126/science.2932797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levin ER, Gardner DG, Samson WK. Natriuretic peptides. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;339:321–328. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandey KN. Biology of natriuretic peptides and their receptors. Peptides. 2005;26:901–932. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.09.024. S0196-9781(05)00078-1 [pii] 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drewett JG, Garbers DL. The family of guanylyl cyclase receptors and their ligands. Endocrine Reviews. 1994;15:135–162. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-2-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohapatra SS. Role of natriuretic peptide signaling in modulating asthma and inflammation. Canadian Journal of Physiology & Pharmacology. 2007;85:754–759. doi: 10.1139/Y07-066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenzweig A, Seidman CE. Atrial natriuretic factor and related peptide hormones. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1991;60:229–255. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandey KN. The functional genomics of guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-A: perspectives and paradigms. FEBS J. 2011;278:1792–1807. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08081.x. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anand-Srivastava MB, Trachte GJ. Atrial natriuretic factor receptors and signal transduction mechanisms. Pharmacological Reviews. 1993;45:455–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGrath MF, de Bold ML, de Bold AJ. The endocrine function of the heart. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16:469–477. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koesling D, Schultz G, Bohme E. Sequence homologies between guanylyl cyclases and structural analogies to other signal-transducing proteins. FEBS Letters. 1991;280:301–306. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80317-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandey KN, Singh S. Molecular cloning and expression of murine guanylate cyclase/atrial natriuretic factor receptor cDNA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:12342–12348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lincoln TM, Cornwell TL. Intracellular cyclic GMP receptor proteins. FASEB Journal. 1993;7:328–338. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.2.7680013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muslin AJ. MAPK signalling in cardiovascular health and disease: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Clinical Science. 2008;115:203–218. doi: 10.1042/CS20070430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pimienta G, Pascual J. Canonical and alternative MAPK signaling. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2628–2632. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.21.4930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandey KN, Nguyen HT, Li M, Boyle JW. Natriuretic peptide receptor-A negatively regulates mitogen-activated protein kinase and proliferation of mesangial cells: role of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communications. 2000;271:374–379. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khurana ML, Pandey KN. Catalytic activation of guanylate cyclase/atrial natriuretic factor receptor by combined effects of ANF and GTP gamma S in plasma membranes of Leydig tumor cells: involvement of G-proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;316:392–398. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1052. S0003-9861(85)71052-1 [pii] 10.1006/abbi.1995.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma GD, Nguyen HT, Antonov AS, Gerrity RG, von Geldern T, Pandey KN. Expression of atrial natriuretic peptide receptor-A antagonizes the mitogen-activated protein kinases (Erk2 and P38MAPK) in cultured human vascular smooth muscle cells. Molecular & Cellular Biochemistry. 2002;233:165–173. doi: 10.1023/a:1015882302796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dignam JD. Preparation of extracts from higher eukaryotes. Methods in Enzymology. 1990;182:194–203. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82017-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vellaichamy E, Khurana ML, Fink J, Pandey KN. Involvement of the NF-kappa B/matrix metalloproteinase pathway in cardiac fibrosis of mice lacking guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor A. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19230–19242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411373200. M411373200 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.M411373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrara N, Gerber HP. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in angiogenesis. Acta Haematologica. 2001;106:148–156. doi: 10.1159/000046610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patan S. Vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Cancer Treatment & Research. 2004;117:3–32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8871-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerbel R, Folkman J. Clinical translation of angiogenesis inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:727–739. doi: 10.1038/nrc905. 10.1038/nrc905 nrc905 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruderman JV. MAP kinase and the activation of quiescent cells. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 1993;5:207–213. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson PR, Yamamura S, Mureebe L, Itoh H, Kent KC. Smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation are mediated by distinct phases of activation of the intracellular messenger mitogen-activated protein kinase. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 1998;27:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(98)70298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bornfeldt KE, Krebs EG. Crosstalk between protein kinase A and growth factor receptor signaling pathways in arterial smooth muscle. Cellular Signalling. 1999;11:465–477. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(99)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cardoso LE, Little PJ, Ballinger ML, Chan CK, Braun KR, Potter-Perigo S, Bornfeldt KE, Kinsella MG, Wight TN. Platelet-derived growth factor differentially regulates the expression and post-translational modification of versican by arterial smooth muscle cells through distinct protein kinase C and extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285:6987–6995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088674. M109.088674 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.M109.088674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ladetzki-Baehs K, Keller M, Kiemer AK, Koch E, Zahler S, Wendel A, Vollmar AM. Atrial natriuretic peptide, a regulator of nuclear factor-kappaB activation in vivo. Endocrinology. 2007;148:332–336. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandey KN. Emerging Roles of Natriuretic Peptides and their Receptors in Pathophysiology of Hypertension and Cardiovascular Regulation. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2008;2:210–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2008.02.001. 10.1016/j.jash.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliver PM, John SW, Purdy KE, Kim R, Maeda N, Goy MF, Smithies O. Natriuretic peptide receptor 1 expression influences blood pressures of mice in a dose-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2547–2551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedram A, Razandi M, Levin ER. Natriuretic peptides suppress vascular endothelial cell growth factor signaling to angiogenesis. Endocrinology. 2001;142:1578–1586. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.4.8099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandey KN, Pavlou SN, Inagami T. Identification and characterization of three distinct atrial natriuretic factor receptors. Evidence for tissue-specific heterogeneity of receptor subtypes in vascular smooth muscle, kidney tubular epithelium, and Leydig tumor cells by ligand binding, photoaffinity labeling, and tryptic proteolysis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988;263:13406–13413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugimoto T, Haneda M, Togawa M, Isono M, Shikano T, Araki S, Nakagawa T, Kashiwagi A, Guan KL, Kikkawa R. Atrial natriuretic peptide induces the expression of MKP-1, a mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase, in glomerular mesangial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:544–547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prins BA, Weber MJ, Hu RM, Pedram A, Daniels M, Levin ER. Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits mitogen-activated protein kinase through the clearance receptor. Potential role in the inhibition of astrocyte proliferation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:14156–14162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hutchinson HG, Trindade PT, Cunanan DB, Wu CF, Pratt RE. Mechanisms of natriuretic-peptide-induced growth inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovascular Research. 1997;35:158–167. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chrisman TD, Garbers DL. Reciprocal antagonism coordinates C-type natriuretic peptide and mitogen-signaling pathways in fibroblasts. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:4293–4299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pandey KN, Pavlou SN, Inagami T. Identification and characterization of three distinct atrial natriuretic factor receptors. Evidence for tissue-specific heterogeneity of receptor subtypes in vascular smooth muscle, kidney tubular epithelium, and Leydig tumor cells by ligand binding, photoaffinity labeling, and tryptic proteolysis. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:13406–13413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leitman DC, Andresen JW, Catalano RM, Waldman SA, Tuan JJ, Murad F. Atrial natriuretic peptide binding, cross-linking, and stimulation of cyclic GMP accumulation and particulate guanylate cyclase activity in cultured cells. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:3720–3728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamad AM, Johnson SR, Knox AJ. Antiproliferative effects of NO and ANP in cultured human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L910–L918. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.5.L910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klaiber M, Dankworth B, Kruse M, Hartmann M, Nikolaev VO, Yang RB, Volker K, Gassner B, Oberwinkler H, Feil R, Freichel M, Groschner K, Skryabin BV, Frantz S, Birnbaumer L, Pongs O, Kuhn M. A cardiac pathway of cyclic GMP-independent signaling of guanylyl cyclase A, the receptor for atrial natriuretic peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18500–18505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103300108. 1103300108 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.1103300108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haneda M, Araki S, Sugimoto T, Togawa M, Koya D, Kikkawa R. Differential inhibition of mesangial MAP kinase cascade by cyclic nucleotides. Kidney International. 1996;50:384–391. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayashi D, Kudoh S, Shiojima I, Zou Y, Harada K, Shimoyama M, Imai Y, Monzen K, Yamazaki T, Yazaki Y, Nagai R, Komuro I. Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1. Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;322:310–319. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Armesilla AL, Lorenzo E, Gomez del Arco P, Martinez-Martinez S, Alfranca A, Redondo JM. Vascular endothelial growth factor activates nuclear factor of activated T cells in human endothelial cells: a role for tissue factor gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2032–2043. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schinelli S, Zanassi P, Paolillo M, Wang H, Feliciello A, Gallo V. Stimulation of endothelin B receptors in astrocytes induces cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation and c-fos expression via multiple mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8842–8853. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-08842.2001. 21/22/8842 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mayo LD, Kessler KM, Pincheira R, Warren RS, Donner DB. Vascular endothelial cell growth factor activates CRE-binding protein by signaling through the KDR receptor tyrosine kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:25184–25189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102932200. 10.1074/jbc.M102932200 M102932200 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Isono M, Haneda M, Maeda S, Omatsu-Kanbe M, Kikkawa R. Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits endothelin-1-induced activation of JNK in glomerular mesangial cells. Kidney International. 1998;53:1133–1142. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00869.x. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swart JM, Chiles TC. Rescue of CH31 B cells from antigen receptor-induced apoptosis by inhibition of p38 MAPK. Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communications. 2000;276:417–421. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swart JM, Bergeron DM, Chiles TC. Identification of a membrane Ig-induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase module that regulates cAMP response element binding protein phosphorylation and transcriptional activation in CH31 B cell lymphomas. Journal of Immunology. 2000;164:2311–2319. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rius J, Martinez-Gonzalez J, Crespo J, Badimon L. Involvement of neuron-derived orphan receptor-1 (NOR-1) in LDL-induced mitogenic stimulus in vascular smooth muscle cells: role of CREB. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:697–702. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000121570.00515.dc. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000121570.00515.dc 01.ATV.0000121570.00515.dc [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cuenda A, Rousseau S. p38 MAP-kinases pathway regulation, function and role in human diseases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1773:1358–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]