Abstract

Background

The signaling mechanisms that regulate the recruitment of bone marrow (BM)-derived cells to the injured heart are not well known. Notch receptors mediate binary cell fate determination and may regulate the function of BM-derived cells. However, it is not known whether Notch1 signaling in BM-derived cells mediates cardiac repair following myocardial injury.

Methods and Results

Mice with postnatal cardiac-specific deletion of Notch1 exhibit similar infarct size and heart function following ischemic injury as control mice. However, mice with global hemizygous deletion of Notch1 (N1+/−) developed larger infarct size and worsening heart function. When the BM of N1+/− mice were transplanted into wild-type (WT) mice, infarct size and heart function were worsened and neovascularization in the infarct border area was reduced compared to WT mice transplanted with WT BM. In contrast, transplantation of WT BM into N1+/− mice lessened the myocardial injury observed in N1+/− mice. Indeed, hemizygous deletion of Notch1 in BM-derived cells leads to decreased recruitment, proliferation, and survival of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC). Compared to WT MSC, injection of N1+/− MSC into the infarcted heart leads to increased myocardial injury, whereas injection of MSC overexpressing Notch intracellular domain leads to decreased infarct size and improved cardiac function.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that Notch1 signaling in BM-derived cells is critical for cardiac repair, and suggest that strategies that increase Notch1 signaling in BM-derived MSC could have therapeutic benefits in patients with ischemic heart disease.

Keywords: stem cells, gene therapy, myocardial infarction, angiogenesis

Adult bone marrow (BM)-derived cells, including hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells (MSC), are mobilized and recruited to the heart in response to myocardial injury 1. Indeed, several clinic studies suggest that injection of BM-derived stem cells including MSCs could have therapeutic benefits in the treatment of ischemic heart diseases 2-7. However, the precise signaling mechanisms that govern the function of BM-derived cells and MSCs are not known.

Notch receptors are important regulators of embryonic development and cardiovascular homeostasis 8-11. Through local cell-cell interactions, they specify cell fate and tissue patterning and are important mediators of stem cell self-renewal, expansion, survival, and differentiation 12-14. In mammals, four Notch receptors (Notch1–Notch4) and five structurally similar Notch ligands (Delta-like1, Delta-like3, Delta-like4, Jagged1, and Jagged2) have been identified 8, 15. Both Notch1 and Jagged-1 have been shown to be critical for vasculogenesis and blood flow recovery in ischemic limbs 16, 17. In the heart, Notch1 regulates the fate of cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs), stimulates proliferation of immature cardiomyocytes, and limits the extent of cardiomyocytes hypertrophic response 10, 18-20. Selective overexpression of NICD in cardiomyocytes leads to multiple cardiac defects, whereas, cardiac-specific silencing of all four mammalian Notch receptors in early cardiogenesis perturbs cardiac morphogenesis 21. Indeed, several recent studies suggest that Notch signaling may protect the heart after myocardial infarction 18, 21, 22. However, it is not known whether Notch signaling could contribute to cardiac repair by regulating the function of postnatal cardiomyocytes or BM-derived cells.

Methods

Animals

Notch1 heterozygous knockout (N1+/−) mice were generated as described 23. GFP positive N1+/− (GFP-N1+/−) mice were generated by crossing GFP transgenic mice (Jackson Laboratory) with N1+/− mice. Cardiac-specific Notch1 knockout (C-N1−/−) mice were generated by crossing αMHC-Cre mice 24 with Notch1flox/flox mice 25. All mice were congenic strains on C57/Bl6 background. The Standing Committee on Animals at Harvard Medical School approved all protocols pertaining to experimentation with animals.

LAD Ligation/Myocardial Infarction Model

Twelve- to 13-week-old male littermate-matched mice were subjected to left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) ligation as described (see suppl. Materials and Methods). In the MSC intramyocardial injection experiments, the infarct border region was injected at 4 sites with 5×105 MSC. All mice were operated under the same conditions by the same operator, who was blinded to the genotype of the mice.

Bone Marrow Transplantation

The BM transplantation was performed as described (see suppl. Materials and Methods). Four weeks after BM transplantation (BMT), LAD ligation was performed. The chimerism of BMT mice ranged between 5-10%.

Echocardiographic Assessment of LV Function

Echocardiography (Vevo 770, VisualSonics Inc.) was performed on conscious mice to avoid potential effects of anesthesia as described 26.

Evaluation of Myocardial Infarct Size and Neovascularization

Myocardial infarct size and neovascularization were determined as described (see suppl. Materials and Methods).

Immunohistochemistry, Immunofluorescence, and Immunoblotting

Immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, and immunoblotting were performed with standard protocols (see suppl. Materials and Methods).

Isolation and Culture of Bone Marrow-derived MSC

Isolation and purification of MSC were performed as described (see suppl. Materials and Methods) 27. The cell surface markers that were used to identify mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) were positive staining for CD105 and Sca-1 and negative staining for CD45, CD34, and c-Kit 28. In some experiments, MSC at passage 4 were used for intramyocardial injection following LAD ligation. For NICD-adenoviral infection studies, MSC were infected with Ad.GFP or Ad.NICD at a multiplicity of infection of 100 for 24 hours 11.

MSC Migration and Co-culture Assay

Neonatal cardiomyocytes were isolated as described 29. MSC migration assay was performed as described (see suppl. Materials and Methods) 30.

Real-time PCR

The primers that were used were as follows: Hey1 forward: 5′-GCGCGGACGAGAATGGAAA -3′, Hey1 reverse: 5′-TCAG GTGATCCACAGTCATCTG-3′; HeyL forward: 5′-CAGCCCTT CGCAGATGCAA-3′, HeyL reverse: 5′-CCAATCGTCGCAATTCAGAAAG-3′; CSF3R forward: 5′-CTGATCTTCTTGCTACTCCCCA-3′, CSF3R reverse: 5′-GGTGTAGTTCAA GTGAGGCAG-3′; CXCR4 forward: 5′-GAAGTGGGGTCTGGAGACTAT-3′, CXCR4 reverse: 5′-TTGCCGACTATGCCAGTCA AG-3′.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean with 95% confidence intervals. Some in vitro experimental results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The data among groups were compared with 1 way ANOVA. The mortality was compared with Pearson Chi-square analysis (SPSS, version 13). A P value of <0.05 was taken to be statistically significant.

Results

Protective Role of Notch1 Following Myocardial Injury

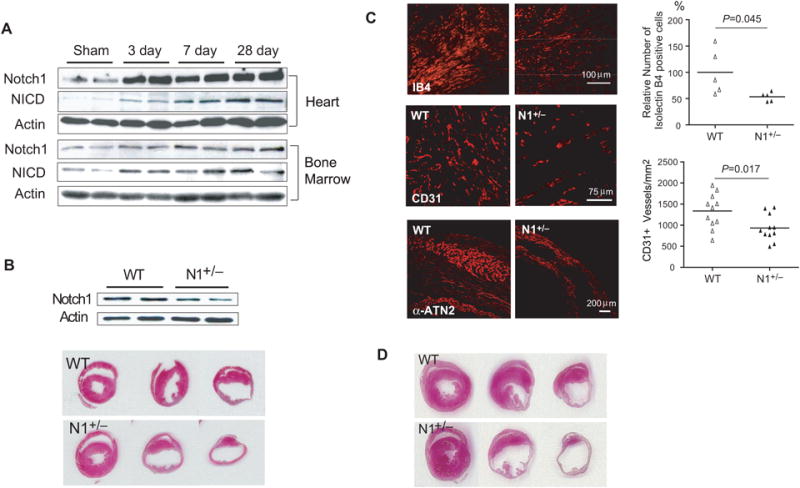

Notch1 and activated Notch1 (NICD) expression were upregulated in the heart and BM after LAD ligation (Figure 1A). Because homozygous deletion of Notch1 leads to embryonic lethality 31-33, we used global Notch1 heterozygous knockout (N1+/−) mice 31 (Figure 1B, top panels), which are viable and phenotypically normal compared to WT littermate mice (data not shown). Following LAD ligation, there were no difference in mortality between N1+/− mice and WT littermate mice (14% vs. 0%, p=0.142, n=14 each). Seven days after LAD ligation, myocardial infarct size was larger in N1+/− mice compared to WT mice (34.9 %, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 27.8 to 42.0%, vs. 25.4%, 95% CI: 19.1 to 31.7%, p=0.048) (Figure 1B, bottom panels). Echocardiography showed decreased fractional shortening (FS) and ejection fraction (EF) in N1+/− mice compared of WT mice (Table 1, rows of “WT vs. N1+/− Mice).

Figure 1. Myocardial infarction of WT and N1+/− mice.

(A) Notch1 and NICD expression in the infarct border zone (top panels) and bone marrow (bottom panels) of WT mice following LAD ligation. (B) Heart Notch1 expression in WT and N1+/− mice (left top panel). H&E staining of the infarcted hearts in ligation, papillary, apex level 7 days after LAD ligation. (C) Isolectin B4 staining (top panels), and CD31 staining (middle panels) in the infarct border area. α-actinin-2 staining in the infarction area (bottom panels). (D) H&E staining 4 weeks after LAD ligation.

Table 1. Cardiac dimensions and systolic function evaluated by echocardiography.

| Pre | Post | P* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| WT or control mean (95% CI) | N1deficiency or NICD mean (95% CI) | WT or control mean (95% CI) | N1deficiency or NICD mean (95% CI) | ||

| WT vs. N1+/− (7 days) | |||||

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.44 (3.223.66) | 3.28 (3.043.52) | 4.96 (4.515.41) | 5.38 (5.015.75) | 0.06 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 1.92 (1.722.12) | 1.77 (1.482.06) | 3.72 (3.174.27) | 4.57 (3.985.16) | 0.046 |

| FS (%) | 45.0 (40.749.3) | 46.3 (39.852.8) | 25.7 (21.030.4) | 15.5 (10.021.0) | 0.011 |

| EF (%) | 76.6 (72.181.1) | 78.3 (72.684.0) | 49.6 (41.457.8) | 31.9 (21.542.3) | 0.016 |

|

| |||||

| WT vs. N1+/− (28 days) | |||||

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.29 (2.953.63) | 3.34 (3.183.51) | 5.05 (4.425.67) | 5.59 (5.166.02) | 0.024 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 1.64 (1.291.99) | 1.65 (1.112.18) | 3.83 (3.384.28) | 4.74 (4.065.42) | 0.041 |

| FS (%) | 50.4 (44.056.8) | 50.1 (36.663.5) | 22.8 (19.626.1) | 13.6 (6.820.4) | 0.025 |

| EF (%) | 82.5 (76.588.4) | 81.6 (68.294.9) | 45.9 (40.651.2) | 28.7 (15.441.9) | 0.024 |

|

| |||||

| Control vs. C-N1+/− | |||||

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.59 (3.263.93) | 3.58 (3.343.81) | 4.18 (4.034.34) | 4.12 (3.914.34) | 0.627 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 1.99 (1.792.19) | 1.90 (1.632.17) | 3.14 (2.753.53) | 2.82 (2.433.21) | 0.241 |

| FS (%) | 44.7 (43.346.1) | 45.1 (41.249.0) | 26.1 (20.531.8) | 30.8 (27.734.0) | 0.162 |

| EF (%) | 76.9 (75.378.5) | 77.5 (73.681.4) | 50.6 (40.760.6) | 60.1 (56.663.5) | 0.119 |

|

| |||||

| WT-WT BMT vs. N1+/− - WT BMT | |||||

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.20 (3.023.38) | 2.96 (2.743.17) | 4.66 (4.524.79) | 4.88 (4.745.02) | 0.044 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 1.94 (1.822.06) | 1.93 (1.852.01) | 3.67 (3.473.87) | 4.24 (4.064.42) | 0.001 |

| FS (%) | 39.2 (36.242.3) | 36.3 (34.937.7) | 21.2 (18.024.4) | 13.1 (10.915.3) | 0.001 |

| EF (%) | 70.7 (67.274.2) | 67.5 (65.669.4) | 42.8 (37.348.2) | 27.9 (23.732.1) | 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| WT-WT BMT vs. WT - N1+/− BMT | |||||

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.39 (3.253.53) | 3.36 (3.093.63) | 5.20 (4.735.67) | 5.03 (4.605.46) | 0.601 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 2.09 (1.952.23) | 1.99 (1.792.19) | 4.30 (3.774.83) | 4.25 (3.704.80) | 0.893 |

| FS (%) | 38.6 (36.341.0) | 40.7 (37.044.5) | 17.9 (14.721.0) | 16.0 (9.822.2) | 0.546 |

| EF (%) | 69.9 (67.072.8) | 72.4 (67.976.8) | 36.6 (30.642.6) | 32.7 (21.444.0) | 0.496 |

|

| |||||

| WT MSC vs. N1+/− MSC | |||||

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.05 (2.883.21) | 2.96 (2.833.09) | 4.43 (4.324.53) | 4.70 (4.484.92) | 0.044 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 1.65 (1.431.88) | 1.53 (1.421.63) | 3.62 (3.383.85) | 4.09 (3.724.46) | 0.049 |

| FS (%) | 45.9 (41.050.8) | 48.3 (44.552.2) | 18.0 (13.622.4) | 12.1 (8.815.4) | 0.049 |

| EF (%) | 78.3 (72.484.3) | 80.8 (77.184.6) | 36.0 (34.137.9) | 26.4 (19.733.0) | 0.035 |

|

| |||||

| Ad. GFP MSC vs. Ad. NICD MSC | |||||

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.18 (2.843.51) | 2.91 (2.743.08) | 4.47 (4.224.72) | 4.20 (4.044.37) | 0.086 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 1.62 (1.441.79) | 1.59 (1.491.69) | 3.71 (3.523.90) | 3.26 (3.023.49) | 0.009 |

| FS (%) | 48.7 (44.153.4) | 45.0 (40.050.1) | 17.0 (14.020.0) | 22.0 (18.225.7) | 0.049 |

| EF (%) | 81.0 (75.986.1) | 78.0 (73.083.0) | 37.8 (29.446.2) | 46.6 (39.553.7) | 0.041 |

There was less vascularization in the infarct border zone of N1+/− mice than that in WT mice. Relative number of isolectin B4 positive cells in N1+/− mice was 53.5% (95% CI: 45.0 to 61.9%) compared to WT mice (100%) (p=0.045, Figure 1C, top panel). This corresponded to decreased number of CD31+ vessels in N1+/− mice compared to WT mice (933 vessel number/mm2 [95% CI: 740 to 1127], vs. 1336 vessel number/mm2 [95% CI: 1082 to 1589], p=0.017) (Figure 1C, middle panel). The number of surviving cardiomyocytes as determined by α-actinin-2 staining was greatly reduced in N1+/− mice than in WT mice (Figure 1C, bottom panels). Similar to what was observed at 7 days after LAD ligation, myocardial infarct size was larger in N1+/− mice compared to that of WT mice at 28 days after LAD ligation (41.3% [95% CI: 39.4 to 43.1%] vs. 30.0% [95% CI: 24.4 to 35.6%], p=0.013, n=10 each) (Figure 1D). Echocardiography showed enlarged cardiac dimensions in N1+/− mice compared to WT mice. This correlated with decreased cardiac function in N1+/− mice compared to WT mice (Table 1).

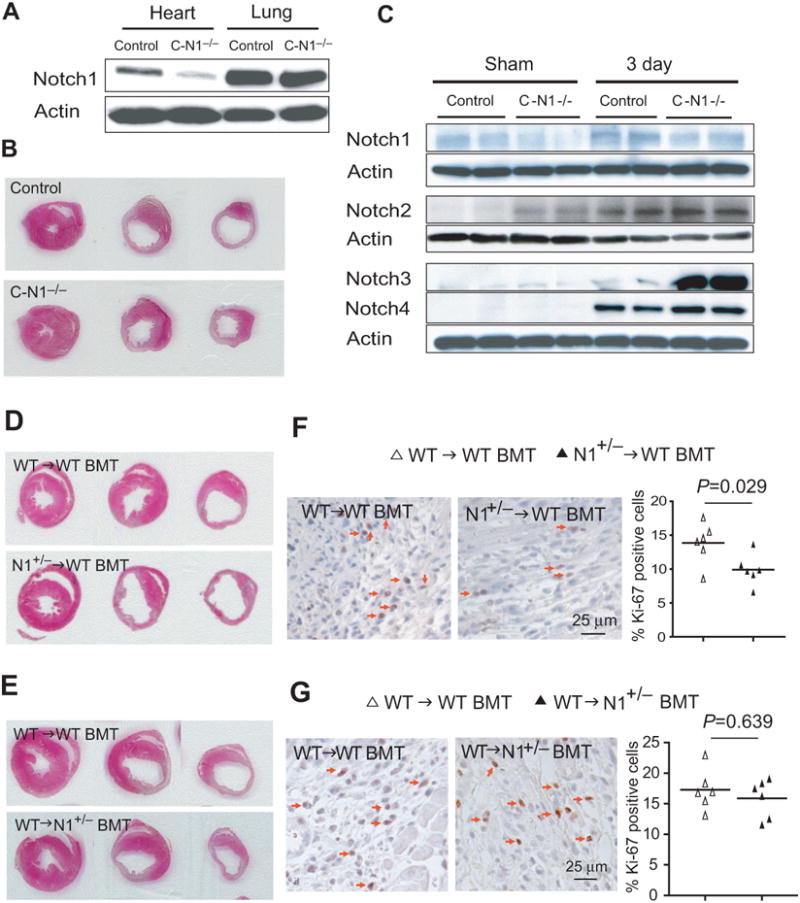

Notch1 in Postnatal Cardiomyocytes Does Not Contribute to Cardiac Repair

Because αMHC expression peaks after birth and is maintained at high levels during the postnatal period in both atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes 24, cardiac-specific Notch1 deletion in C-N1−/− mice occurs predominantly in postnatal cardiomyocytes (Figure 2A). C-N1−/− mice develop normally and have normal cardiac dimensions and function as control mice (i.e., αMHC-Cre and Notch1flox/flox). Following LAD ligation, C-N1−/− mice showed similar mortality rate (20% vs. 13%, p=0.67, n=10 in C-N1−/− mice and 8 in control mice), infarct size (44.3% [95% CI: 39.2 to 49.3%] vs. 40.8% [95% CI: 21.9 to 59.6%], p=0.706) (Figure 2B), cardiac dimensions and function as control mice (Table 1).

Figure 2. Myocardial infarction in mice with postnatal cardiomyocyte-specific Notch1 deletion, and in WT and Notch1+/− BMT mice.

(A) Notch1 expression in the heart and lung tissues in control (αMHC-Cre) and C-N1−/− mice. (B) H&E staining of the infarcted hearts at ligation, papillary, apex level. (C) Notch1, Notch2, Notch3, and Notch4 expression in the infarct border zone of control and C-N1−/− mice. (D) H&E staining of the infarcted hearts from WT→WT BMT and N1+/−→WT BMT mice at the level of ligation, papillary, and apex. (E) H&E staining of the infarcted hearts from WT→WT BMT and WT→N1+/− BMT mice at the level of LAD ligation, papillary, and apex level. (F) Ki-67 staining of infarct border zone from WT→WT BMT and N1+/−→WT BMT mice. (G) Ki-67 staining of infarct border zone from WT→WT BMT and WT→N1+/− BMT mice. Arrows indicate Ki-67 positive cells.

Compared to control mice (αMHC-Cre) without LAD ligation (sham), Notch2 and Notch3 expression were slightly higher in C-N1−/− mice. Following LAD ligation, the expression of all Notch receptors was increased in control mice. In C-N1−/− mice, the expression of Notch2 and Notch3 was further augmented compared to control mice (Figure 2C), suggesting that Notch2 and Notch3 may compensate for the loss of Notch1 in cardiomyocytes.

Notch1 in Bone Marrow-Derived Cells Contributes to Cardiac Repair

The N1+/− BMT (N1+/−→WT) mice exhibited similar mortality rate as WT BMT (WT→WT) mice after LAD ligation (23% vs. 14%, p=0.56, n=13 in N1+/− BMT mice and 14 in WT BMT mice). However, following LAD ligation, infarct size was larger in N1+/− BMT mice compared to that of WT BMT mice (49.4% [95% CI: 44.7 to 54.1%] vs. 36.4% [95% CI: 32.1 to 40.8%], p<0.001) (Figures 2D). This corresponded to enlarged cardiac dimensions and reduced cardiac function in N1+/− BMT mice compared to that of WT BMT mice (Table 1).

To determine whether Notch1 in non-BM-derived cells could also contribute to cardiac repair, we transplanted BM from WT mice into WT and N1+/− recipient mice. Again, survival rates after BMT and LAD ligation were not different and there were no difference in physiological data, cardiac dimensions and heart function before LAD ligation. Surprisingly, there were no differences in infarct size (41.8% [95% CI: 35.2 to 48.4%] vs. 40.8% [95% CI: 33.4 to 48.2%], p=0.843, n=10 each) (Figure 2E), cardiac dimension, and heart function between WT→WT BMT and WT→N1+/− BMT mice following LAD ligation (Table 1), suggesting that Notch1 in non-BM-derived cells does not contribute to cardiac repair following myocardial injury. There were more Ki-67 positive cells in the infarct border zone in WT BMT mice than in N1+/− BMT mice (13.9% [95% CI: 11.2 to 16.5%] vs. 9.9% [95% CI: 7.9 to 11.9%], p=0.029) (Figure 2F). In contrast, WT→WT BMT mice showed similar amounts of Ki-67 positive cells as WT→N1+/− mice (17.1% [95% CI: 12.3 to 21.9%] vs. 15.8% [95% CI: 12.5 to 19.1%], p=0.639) (Figure 2G).

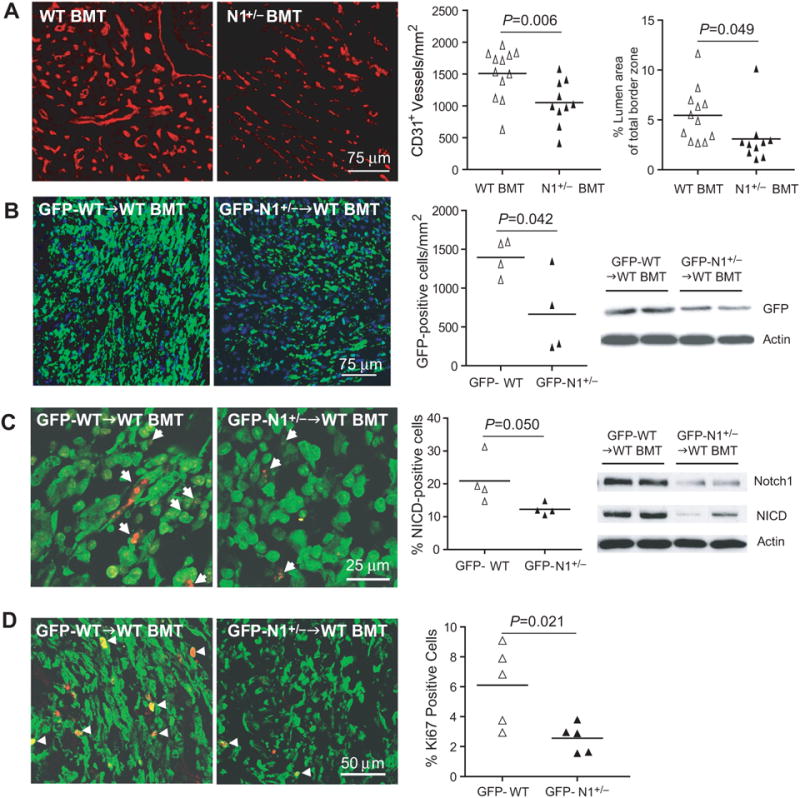

Notch1 Mediates Vascularization and Recruitment of Bone Marrow-derived Cells to the Infarct Border Area

CD31 staining revealed decreased capillary density in the infarct border of N1+/− BMT mice compared with WT BMT mice (CD31+ vessel number/mm2: 1053 [95% CI: 836 to 1270] vs. 1500 [95% CI: 1287 to 1713], p=0.006). This was accompanied by a decrease in the perfusion area in the infarct border area of N1+/− BMT mice compared to WT BMT mice (% lumen area of total border zone: 3.1% [95% CI: 1.5 to 4.8%] vs. 5.5% [95% CI: 3.9 to 7.0], p=0.049) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Notch1 mediates recruitment of BM-derived cells to infarct border zone.

(A) CD31 staining in the infarct border zone in WT BMT and N1+/− BMT mice. (B) GFP positive cells and GFP expression in the infarct border zone in GFP-WT BMT and GFP-N1+/− BMT mice. (C) NICD staining in GFP positive cells and Notch1, NICD expression in the infarct border zone. Arrows indicate NICD positive cells. (D) Ki67 staining in GFP positive cells in the infarct border zone. Arrows indicate double positive staining of each.

To determine whether Notch1 regulates the recruitment of BM-derived cells into the injured heart, we transplanted BM taken from GFP-WT mice or littermate-matched GFP-N1+/− mice into recipient WT mice. Blood cell count and differential were not different between GFP-WT BMT mice and GFP-N1+/− BMT mice (data not shown). Transplantation efficacy were similar between GFP-WT BMT mice and GFP-N1+/− BMT mice (88.6% vs. 86.9%, p=0.58, n=20 each). Three days following LAD ligation, GFP-N1+/− BMT mice showed decreased GFP expression and GFP-positive cells in the infarct border area compared to GFP-WT BMT mice (GFP-positive cell number/mm2: 664 [95% CI: 78 to 1251] vs. 1395 [95% CI: 1133 to 1658], p=0.042) (Figure 3B). The BM-derived NICD positive cells in the infarct border area were also decreased in GFP-N1+/− BMT mice compared to GFP-WT BMT mice (% NICD positive cells: 12.3% [95% CI: 10.2 to 14.3%] vs. 20.9% [95% CI: 12.8 to 29.0%], p=0.050) (Figure 3C, left panels). This corresponded to decreased Notch1 and NICD expression in the infarct border area (Figure 3C, right panel). Using Ki-67 staining, we found decreased proliferation of BM-derived cells in the infarct border zone of GFP-N1+/− BMT mice compared to that of GFP-WT BMT mice (2.6 % [95% CI: 1.9 to 3.3%] vs. 5.8% [95% CI: 3.4 to 8.3%], p=0.021) (Figure 3D).

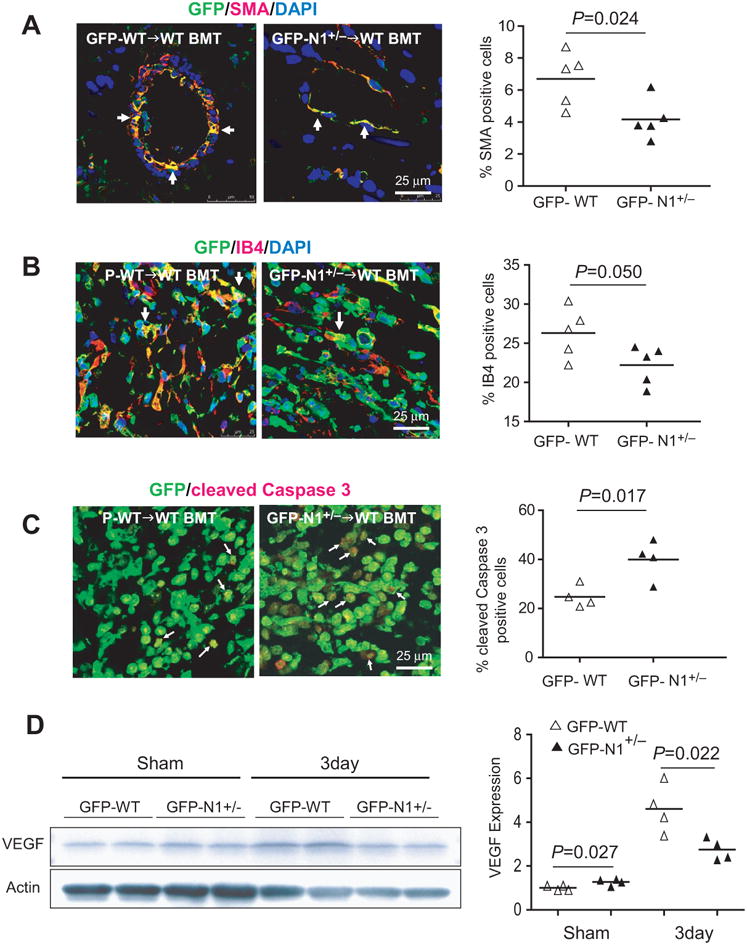

Seven days following LAD ligation, there was decreased proportions of GFP+ SMA+ cells (4.1% [95% CI: 2.8 to 5.5%] vs. 6.7% [95% CI: 5.1 to 8.3%], p=0.024) and GFP+ IB4+ cells (22.3% [95% CI: 20.0 to 24.5%] vs. 26.2% [95% CI: 23.3 to 29.1%], p=0.050) relative to the total number of GFP+ cells in the infarct border area of GFP-N1+/− BMT mice compared to GFP-WT BMT mice (Figure 4A and 4B). More definitive staining of smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells with SM MHC and CD31, respectively, revealed little if any staining (data not shown), suggesting that BM-derived cells were vascular-like rather than definitive vascular cells. However, co-staining the IB4+ and SMA+ cells for CD68 indicate that most of these trans-differentiated vascular-like cells were not juxtaposed macrophages (data not shown). Furthermore, very rare, if any, GFP+ cells were found to co-stain with α-actinin-2 or cardiac troponin T in either GFP-N1+/− BMT or GFP-WT BMT mice. Deficiency of Notch1 in BM also leads to increased apoptosis of BM-derived cells in the infarct border zone compared to WT BM (cleaved-Caspase3+ cells: 39.9% [95% CI: 30.8 to 49.1%] vs. 24.7% [95% CI: 19.7 to 29.8%], p=0.017) (Figure 4C). Although VEGF expression was increased in both WT BMT and N1+/− BMT mice after LAD ligation, WT BMT mice showed higher VEGF expression than N1+/− BMT mice (Figure 4D). These findings suggest that Notch1 in BM-derived cells contributes to vascularization through paracrine effects rather than transdifferentiation into vascular cells.

Figure 4. Notch1 regulates vascularization and BM-derived cells apoptosis in the infarct border zone.

Co-staining of GFP positive cells with(A) smooth muscle actin (SMA), (B) isolectin B4 (IB4), and (C) cleaved-Caspase3, and (D) expression of VEGF in the infarct border zone.

Notch1 in Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Mediates Cardiac Repair

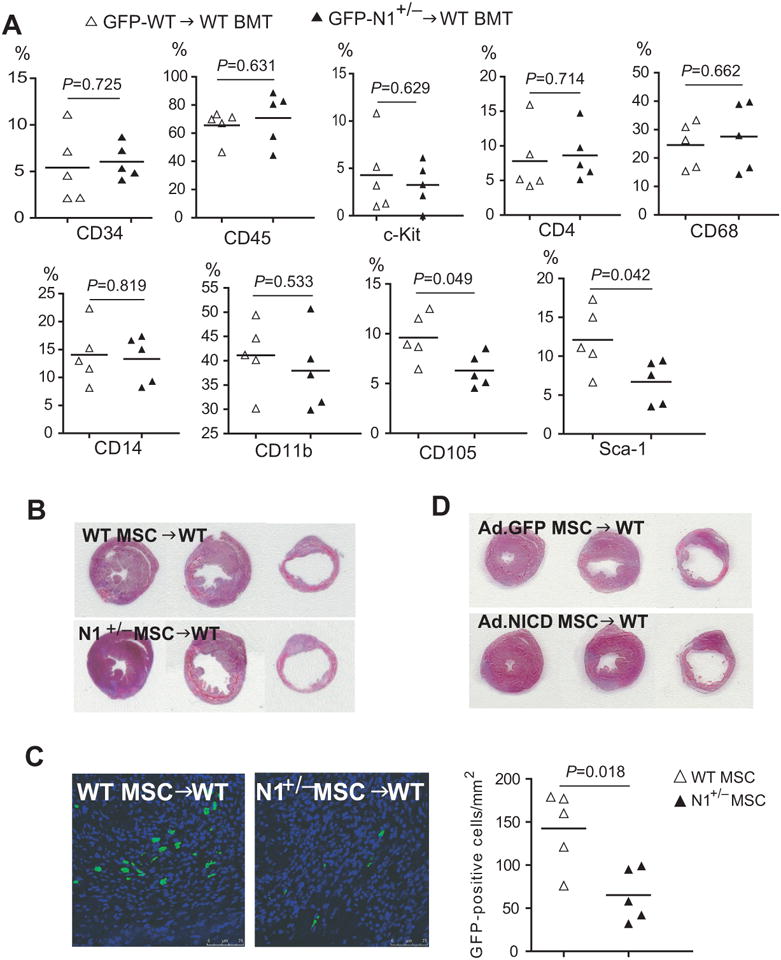

To determine which subgroups of BM-derived cells are regulated by Notch1, we co-stained GFP+ cells in the heart with different cell markers at 1 day following LAD ligation. In contrast to CD34+, CD45+, c-kit+, CD4+, CD68+, CD14+, and CD11b+ cells, we found more CD105+ and Sca-1+ cells in the GFP-WT BMT mice compared to GFP-N1+/− BMT mice (Figure 5A). Because MSC express CD105 and Sca-1, and are negative for CD34, CD45, c-kit, and CD4 28, these findings suggest that Notch1 may increase the recruitment of BM-derived MSC to the injured heart.

Figure 5. Critical role of Notch1 in MSC in mediating cardiac repair.

(A) Ratio of different subgroups of BM-derived cells in the heart following myocardial infarction. (B) H&E staining of the infarcted hearts at the level of ligation, papillary, and apex following intramyocardial injection of WT and Notch1+/− MSC. (C) Presence of GFP positive MSC in the infarcted hearts 7 days after LAD ligation and intramyocardial MSC injection. (D) H&E staining of the infarcted hearts at the level of ligation, papillary, and apex following intramyocardial injection of GFP-adenoviral infected or NICD-adenoviral infected MSC.

To investigate whether Notch1 in MSC directly mediate cardiac repair process, LAD ligation was performed on C57Bl/6 WT mice followed by intramyocardial injection of 5 × 105 GFP-WT or GFP-N1+/− MSC at passage 4. Following LAD ligation, infarct size was larger with N1+/− MSC injection compared to WT MSC injection (48.5% [95% CI: 46.0 to 50.9%] vs. 42.5% [95% CI: 37.9 to 47.1%], p=0.036, n=12 each) (Figure 5B). Similarly, echocardiography showed greater cardiac dimensions and decreased cardiac function with N1+/− MSC injection compared to WT MSC injection (Table 1). Indeed, there was a greater number of MSC in the infarct border zone following injection of WT MSC compared to injection of N1+/− MSC (Figure 5C). Conversely, injection of NICD-adenoviral infected MSC leads to decreased infarct size and improved heart function compared to GFP-adenoviral infected MSC (control) (infarct size: 38.9% [95% CI: 34.7 to 43.0%] vs. 43.8% [95% CI: 41.6 to 46.1%], p=0.05, n=12 each) (Figure 5D and Table 1). These findings suggest that Notch1 in MSC is a critical mediator of cardiac repair following myocardial ischemia.

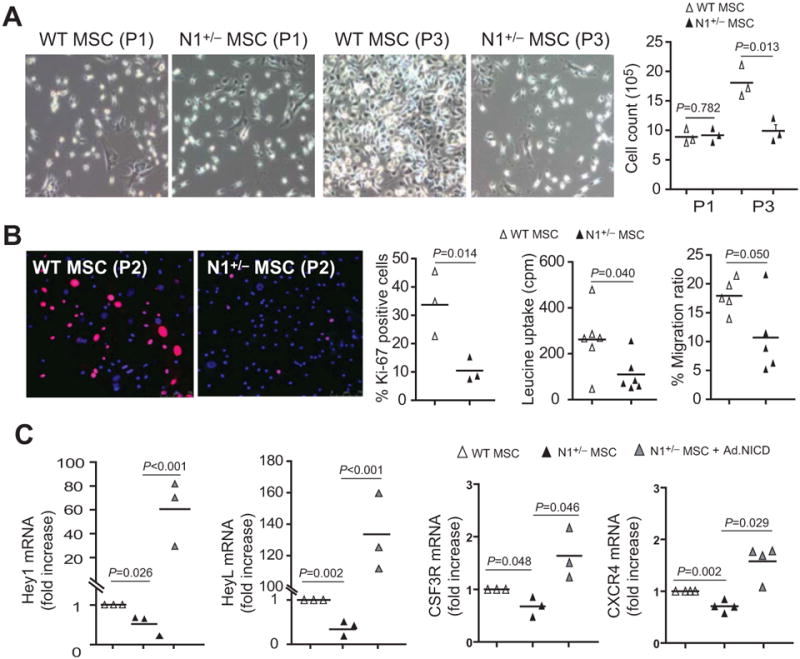

Notch1 Regulates MSC Proliferation and Function

When MSC were isolated and cultured, there was no observable difference in cell number between WT and N1+/− MSC in primary and passage 1 (P1) cultures. However, after 2-3 passages, N1+/− MSC have less proliferative capacity compared to WT MSC (Figure 6A). At cellular passage 2, MSC from N1+/− mice bone marrow exhibited decreased Ki-67 staining compared to MSC from WT mice (% Ki-67 positive cells: 10.5 ± 5.6% vs. 33.6 ± 15.6%, p=0.014) (Figure 6B, left panels). This corresponded with decreased protein synthesis (i.e., [3H]-Leucine incorporation) in N1+/− MSC compared to WT MSC (110.2 ± 77.9 cpm vs. 262.7 ± 137.9 cpm, p=0.040) (Figure 6B, second right panel). Furthermore, N1+/− MSC showed impaired migratory ability compared to WT MSC (% migration ratio: 10.7 ± 6.5% vs. 17.9 ± 2.8%, p=0.050) (Figure 6B, right panel).

Figure 6. Notch1 regulates the function of BM-derived MSC.

(A) MSC culture and cell count at passage 1 (P1) and passage 3 (P3). (B) Ki-67 (pink) and DAPI (blue) staining of MSC at passage 2 (P2). [3H]-Leucine uptake of P2 MSC (middle panel). Transwell migration ratio of MSC (right panel). (C) MSC mRNA expression of Hey1, HeyL, CSF3R, and CXCR4, with and without Ad-NICD infection.

The expression of Notch1 target genes, Hey1 and HeyL, were reduced in N1+/− MSC compared to that of WT MSC. Overexpression of NICD in N1+/− MSC with NICD-adenoviral infection increased their expression (Figure 6C, left panels). The expression of other Notch downstream targets such as Hes3, Hes5, and Hes7 were too low to be detected and the expression of Hes1, Hes2, and Hey2 were not altered (data not shown). Furthermore, the expression of colony stimulating factor 3 receptor (CSF3R) and CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) was also reduced in N1+/− MSC compared to WT MSC, which was reversed by NICD-adenoviral infection (Figure 6C, right panels). However, the expression of their ligands, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) were similar between WT and N1+/− MSC (data not shown).

Discussion

We have shown that Notch1 in BM-derived cells are involved in cardiac repair following myocardial infarction. The protective mechanism may be due, in part, to Notch1-mediated neovascularization in the infarcted hearts. Indeed, isolectin B4 and CD31 staining for microvessel formation in the infarct border zone as well as VEGF expression was greatly reduced in N1+/− mice. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing potential cross-talk between Notch and other vascular signaling pathways involving VEGF, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), Wnt, hedgehog, and bone morphogenic protein (BMP) in regulating arteriogenesis 9, 34-38. These results are also consistent with recent hindlimb ischemia study, which showed that inactivation of Jagged-1-mediated Notch signaling leads to inhibition of postnatal vasculogenesis in hindlimb ischemia via impairment of proliferation, survival, and mobilization of bone marrow-derived EPCs 17.

Interestingly, the loss of Notch1 in postnatal cardiomyocyte did not affect the severity of myocardial injury, suggesting that other Notch receptors may compensate for the loss-of-function of cardiomyocyte Notch1. Indeed, increased expression of other Notch receptors such as Notch2 and Notch3 was observed in cardiomyocyte-specific Notch1 knockout mice. This increase in Notch expression after infarction may be partly attributed to Notch expression in recruited BM-derived cells. Furthermore, we could not exclude the contributions of Notch1 signaling in immature cardiomyocytes and/or cardiac progenitor cells (CPC). CPC does not express αMHC, and thus, is not subjected to Cre-mediated excision with αMHC-Cre. Indeed, transplantation of CPC sheet could improve cardiac function through paracrine mechanisms mediated via the sVCAM-1/VLA-4 signaling pathway 39.

The importance of Notch signaling in MSC is underscored by the finding that injection of infarcted hearts with MSC overexpressing NICD decreases infarct size and improves heart function similar to what was observed previously 22. Conversely, injection of Notch1-deficient MSC into the infarcted heart leads to increased infarct size and worsening of cardiac function. Decreased expression of Hey1 and HeyL in Notch1-deficient MSC suggests that Hey1 and HeyL are potential targets of Notch1 signaling in BM-derived MSC. Furthermore, downregulation of CSF3R and CXCR4 expression in N1+/− MSC suggests that Notch1 may mediate the mobilization and migration of bone marrow cells through CSF3R and CXCR4 signaling pathways. Indeed, G-CSF/CSF3R and SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling contribute importantly to the recruitment of BM-derived cells to the injured tissues 2, 40-45. Interestingly, Notch1 upregulates CXCR4 46 and mediates BM-derived cells response to GCSF by its intracellular cdc10 repeat domain 47. Taken together, these findings suggest a critical role of Notch signaling in BM-derived MSC in cardiac repair.

We found that BM-derived cells accumulation was greatly reduced in the infarct border zone following myocardial infarction of N1+/− BMT mice compared to WT BMT mice. Once recruited, BM-derived cells could secrete growth factors and cytokines that could promote neovascularization and prevent cardiomyocyte apoptosis in the infarct border zone 2, 39, 40, 48. This paracrine mechanism may be especially important, since most of the cells that are recruited to the infarct border zone are leukocytes. Although the absolute number of inflammatory cells in the infarcted heart was greater in GFP-WT BMT mice compared to N1+/−-WT BMT mice, the proportion of BM-derived CD68+, Cd14+, or CD11b+ cells relative to the total number of GFP+ cells in the infarct border zone following LAD ligation was not different between GFP-WT BMT and N1+/−-WT BMT mice. Indeed, the only BM-derived cell type, whose relative proportion was found to be different between GFP-WT BMT and N1+/−-WT BMT mice after MI, was MSC, suggesting that MSC are the key cell population in Notch1-mediated protection. Nevertheless, the contributory role of Notch1 in BM-derived inflammatory cells such as macrophages in cardiac repair may be very important and need more detail investigation.

Both experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated that BM-derived cells contribute to cardiac repair following myocardial infarction 1-7. However, there are some disparities between these cell-based therapies. For example, pharmacological mobilization of BM-derived cells improved hearts function in animal studies 2, 40, whereas, it does not affect systolic function in human clinical trials49, 50. In addition, contradictory findings between direct infusion of BM–aspirated cells versus pharmacological mobilization of BM–derived stem cells are observed in clinical trials. It is possible that Notch1 signaling promotes this selective mobilization of MSC from BM-derived stem cells. Indeed, a sub-study of STEMMI trial suggests the importance of MSC mobilization for heart function recovery 50. Our findings are in agreement regarding the importance of MSC, but further suggest that modulation of Notch1 signaling in MSC may improve MSC function in terms of mobilization and/or recruitment to the injured heart.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study. As mentioned, IB4 and SMA are not definitive markers for mature endothelial cells and SMC, respectively. Therefore, we performed additional studies with double staining of GFP with CD31 or SM-MHC to evaluate whether BM-derived cells could trans-differentiate into functional mature endothelial cells and SMC. Unfortunately, only a few GFP+ cells were found to co-stain with CD31 in GFP-WT BMT mice, and very rare, if any, in GFP-N1+/− BMT mice. Furthermore, few if any, GFP+ cells were found to co-stain with SM-MHC in either GFP-N1+/− BMT or GFP-WT BMT mice (data not shown). Our results, therefore, suggest that BM-derived cells do not appreciably trans-differentiate into vascular cells in the infarcted heart 51. Finally, we used immunohistochemistry to semi-quantitate the subsets of BM-derived cells in the infarcted heart. Perhaps a more accurate method for quantitating subsets of the cells in the infarct heart is with the use of flow cytometry 52.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was support by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL052233, HL080187, HL071775, HL088533, HL090884, and HL093148).

Footnotes

Disclosures: No disclosures of potential conflicts of interests for all authors

References

- 1.Kajstura J, Rota M, Whang B, Cascapera S, Hosoda T, Bearzi C, Nurzynska D, Kasahara H, Zias E, Bonafe M, Nadal-Ginard B, Torella D, Nascimbene A, Quaini F, Urbanek K, Leri A, Anversa P. Bone marrow cells differentiate in cardiac cell lineages after infarction independently of cell fusion. Circ Res. 2005;96:127–137. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000151843.79801.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y, Fukuda N, Yokoyama S, Kusumi Y, Hagikura K, Kawano T, Takayama T, Matsumoto T, Satomi A, Honye J, Mugishima H, Mitsumata M, Saito S. Effects of G-CSF on cardiac remodeling and arterial hyperplasia in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;549:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strauer BE, Brehm M, Zeus T, Kostering M, Hernandez A, Sorg RV, Kogler G, Wernet P. Repair of infarcted myocardium by autologous intracoronary mononuclear bone marrow cell transplantation in humans. Circulation. 2002;106:1913–1918. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034046.87607.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schachinger V, Erbs S, Elsasser A, Haberbosch W, Hambrecht R, Holschermann H, Yu J, Corti R, Mathey DG, Hamm CW, Suselbeck T, Assmus B, Tonn T, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Intracoronary bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1210–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hare JM, Traverse JH, Henry TD, Dib N, Strumpf RK, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, DeMaria AN, Denktas AE, Gammon RS, Hermiller JB, Jr., Reisman MA, Schaer GL, Sherman W. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study of intravenous adult human mesenchymal stem cells (prochymal) after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2277–2286. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schachinger V, Erbs S, Elsasser A, Haberbosch W, Hambrecht R, Holschermann H, Yu J, Corti R, Mathey DG, Hamm CW, Suselbeck T, Werner N, Haase J, Neuzner J, Germing A, Mark B, Assmus B, Tonn T, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Improved clinical outcome after intracoronary administration of bone-marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction: final 1-year results of the REPAIR-AMI trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2775–2783. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assmus B, Rolf A, Erbs S, Elsasser A, Haberbosch W, Hambrecht R, Tillmanns H, Yu J, Corti R, Mathey DG, Hamm CW, Suselbeck T, Tonn T, Dimmeler S, Dill T, Zeiher AM, Schachinger V. Clinical outcome 2 years after intracoronary administration of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:89–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.843243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiba S. Notch signaling in stem cell systems. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2437–2447. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niessen K, Karsan A. Notch signaling in the developing cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1–11. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00415.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nemir M, Pedrazzini T. Functional role of Notch signaling in the developing and postnatal heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.02.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Takeshita K, Liu PY, Satoh M, Oyama N, Mukai Y, Chin MT, Krebs L, Kotlikoff MI, Radtke F, Gridley T, Liao JK. Smooth muscle Notch1 mediates neointimal formation after vascular injury. Circulation. 2009;119:2686–2692. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.790485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varnum-Finney B, Xu L, Brashem-Stein C, Nourigat C, Flowers D, Bakkour S, Pear WS, Bernstein ID. Pluripotent, cytokine-dependent, hematopoietic stem cells are immortalized by constitutive Notch1 signaling. Nat Med. 2000;6:1278–1281. doi: 10.1038/81390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, Wagers AJ, Girma ER, Weissman IL, Rando TA. Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature. 2005;433:760–764. doi: 10.1038/nature03260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizutani K, Yoon K, Dang L, Tokunaga A, Gaiano N. Differential Notch signalling distinguishes neural stem cells from intermediate progenitors. Nature. 2007;449:351–355. doi: 10.1038/nature06090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolos V, Grego-Bessa J, de la Pompa JL. Notch signaling in development and cancer. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:339–363. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeshita K, Satoh M, Ii M, Silver M, Limbourg FP, Mukai Y, Rikitake Y, Radtke F, Gridley T, Losordo DW, Liao JK. Critical role of endothelial Notch1 signaling in postnatal angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;100:70–78. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000254788.47304.6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon SM, Eguchi M, Wada M, Iwami Y, Hozumi K, Iwaguro H, Masuda H, Kawamoto A, Asahara T. Specific Jagged-1 signal from bone marrow microenvironment is required for endothelial progenitor cell development for neovascularization. Circulation. 2008;118:157–165. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.754978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boni A, Urbanek K, Nascimbene A, Hosoda T, Zheng H, Delucchi F, Amano K, Gonzalez A, Vitale S, Ojaimi C, Rizzi R, Bolli R, Yutzey KE, Rota M, Kajstura J, Anversa P, Leri A. Notch1 regulates the fate of cardiac progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15529–15534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808357105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19.Collesi C, Zentilin L, Sinagra G, Giacca M. Notch1 signaling stimulates proliferation of immature cardiomyocytes. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:117–128. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campa VM, Gutierrez-Lanza R, Cerignoli F, Diaz-Trelles R, Nelson B, Tsuji T, Barcova M, Jiang W, Mercola M. Notch activates cell cycle reentry and progression in quiescent cardiomyocytes. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:129–141. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kratsios P, Catela C, Salimova E, Huth M, Berno V, Rosenthal N, Mourkioti F. Distinct roles for cell-autonomous Notch signaling in cardiomyocytes of the embryonic and adult heart. Circ Res. 2010;106:559–572. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gude NA, Emmanuel G, Wu W, Cottage CT, Fischer K, Quijada P, Muraski JA, Alvarez R, Rubio M, Schaefer E, Sussman MA. Activation of Notch-mediated protective signaling in the myocardium. Circ Res. 2008;102:1025–1035. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krebs LT, Shutter JR, Tanigaki K, Honjo T, Stark KL, Gridley T. Haploinsufficient lethality and formation of arteriovenous malformations in Notch pathway mutants. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2469–2473. doi: 10.1101/gad.1239204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agah R, Frenkel PA, French BA, Michael LH, Overbeek PA, Schneider MD. Gene recombination in postmitotic cells. Targeted expression of Cre recombinase provokes cardiac-restricted, site-specific rearrangement in adult ventricular muscle in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:169–179. doi: 10.1172/JCI119509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radtke F, Wilson A, Stark G, Bauer M, van Meerwijk J, MacDonald HR, Aguet M. Deficient T cell fate specification in mice with an induced inactivation of Notch1. Immunity. 1999;10:547–558. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rottman JN, Ni G, Khoo M, Wang Z, Zhang W, Anderson ME, Madu EC. Temporal changes in ventricular function assessed echocardiographically in conscious and anesthetized mice. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16:1150–1157. doi: 10.1067/S0894-7317(03)00471-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu M, Uemura R, Dai Y, Wang Y, Pasha Z, Ashraf M. In vitro and in vivo effects of bone marrow stem cells on cardiac structure and function. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.da Silva Meirelles L, Caplan AI, Nardi NB. In search of the in vivo identity of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2287–2299. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiang F, Sakata Y, Cui L, Youngblood JM, Nakagami H, Liao JK, Liao R, Chin MT. Transcription factor CHF1/Hey2 suppresses cardiac hypertrophy through an inhibitory interaction with GATA4. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H1997–2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01106.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu ZL, Zhou B, Cong XL, Liu YJ, Xu B, Li YH, Gu J, Han ZC. Hemangiopoietin supports animal survival and accelerates hematopoietic recovery of chemotherapy-suppressed mice. Eur J Haematol. 2007;79:477–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conlon RA, Reaume AG, Rossant J. Notch1 is required for the coordinate segmentation of somites. Development. 1995;121:1533–1545. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krebs LT, Xue Y, Norton CR, Shutter JR, Maguire M, Sundberg JP, Gallahan D, Closson V, Kitajewski J, Callahan R, Smith GH, Stark KL, Gridley T. Notch signaling is essential for vascular morphogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1343–1352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swiatek PJ, Lindsell CE, del Amo FF, Weinmaster G, Gridley T. Notch1 is essential for postimplantation development in mice. Genes Dev. 1994;8:707–719. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.6.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawson ND, Vogel AM, Weinstein BM. sonic hedgehog and vascular endothelial growth factor act upstream of the Notch pathway during arterial endothelial differentiation. Dev Cell. 2002;3:127–136. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang W, Campos AH, Prince CZ, Mou Y, Pollman MJ. Coordinate Notch3-hairy-related transcription factor pathway regulation in response to arterial injury. Mediator role of platelet-derived growth factor and ERK. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23165–23171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brand T. Heart development: molecular insights into cardiac specification and early morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2003;258:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Espinosa L, Ingles-Esteve J, Aguilera C, Bigas A. Phosphorylation by glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta down-regulates Notch activity, a link for Notch and Wnt pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32227–32235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niessen K, Karsan A. Notch signaling in cardiac development. Circ Res. 2008;102:1169–1181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.174318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsuura K, Honda A, Nagai T, Fukushima N, Iwanaga K, Tokunaga M, Shimizu T, Okano T, Kasanuki H, Hagiwara N, Komuro I. Transplantation of cardiac progenitor cells ameliorates cardiac dysfunction after myocardial infarction in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2204–2217. doi: 10.1172/JCI37456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harada M, Qin Y, Takano H, Minamino T, Zou Y, Toko H, Ohtsuka M, Matsuura K, Sano M, Nishi J, Iwanaga K, Akazawa H, Kunieda T, Zhu W, Hasegawa H, Kunisada K, Nagai T, Nakaya H, Yamauchi-Takihara K, Komuro I. G-CSF prevents cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction by activating the Jak-Stat pathway in cardiomyocytes. Nat Med. 2005;11:305–311. doi: 10.1038/nm1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonaros N, Sondermejer H, Schuster M, Rauf R, Wang SF, Seki T, Skerrett D, Itescu S, Kocher AA. CCR3- and CXCR4-mediated interactions regulate migration of CD34+ human bone marrow progenitors to ischemic myocardium and subsequent tissue repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136:1044–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abbott JD, Huang Y, Liu D, Hickey R, Krause DS, Giordano FJ. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha plays a critical role in stem cell recruitment to the heart after myocardial infarction but is not sufficient to induce homing in the absence of injury. Circulation. 2004;110:3300–3305. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147780.30124.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Limana F, Jakoniuk I, Quaini F, Nadal-Ginard B, Bodine DM, Leri A, Anversa P. Mobilized bone marrow cells repair the infarcted heart, improving function and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10344–10349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181177898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang L, Wang YC, Hu XB, Zhang BF, Dou GR, He F, Gao F, Feng F, Liang YM, Dou KF, Han H. Notch-RBP-J signaling regulates the mobilization and function of endothelial progenitor cells by dynamic modulation of CXCR4 expression in mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haider H, Jiang S, Idris NM, Ashraf M. IGF-1-overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells accelerate bone marrow stem cell mobilization via paracrine activation of SDF-1alpha/CXCR4 signaling to promote myocardial repair. Circ Res. 2008;103:1300–1308. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.186742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang YC, Hu XB, He F, Feng F, Wang L, Li W, Zhang P, Li D, Jia ZS, Liang YM, Han H. Lipopolysaccharide-induced Maturation of Bone Marrow-derived Dendritic Cells Is Regulated by Notch Signaling through the Up-regulation of CXCR4. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:15993–16003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901144200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bigas A, Martin DI, Milner LA. Notch1 and Notch2 inhibit myeloid differentiation in response to different cytokines. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2324–2333. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uemura R, Xu M, Ahmad N, Ashraf M. Bone marrow stem cells prevent left ventricular remodeling of ischemic heart through paracrine signaling. Circ Res. 2006;98:1414–1421. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000225952.61196.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ripa RS, Jorgensen E, Wang Y, Thune JJ, Nilsson JC, Sondergaard L, Johnsen HE, Kober L, Grande P, Kastrup J. Stem cell mobilization induced by subcutaneous granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to improve cardiac regeneration after acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: result of the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled stem cells in myocardial infarction (STEMMI) trial. Circulation. 2006;113:1983–1992. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.610469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ripa RS, Haack-Sorensen M, Wang Y, Jorgensen E, Mortensen S, Bindslev L, Friis T, Kastrup J. Bone marrow derived mesenchymal cell mobilization by granulocyte-colony stimulating factor after acute myocardial infarction: results from the Stem Cells in Myocardial Infarction (STEMMI) trial. Circulation. 2007;116:I24–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iwata H, Manabe I, Fujiu K, Takeda N, Eguchi K, Sata M, N R. Bone marrow-derived cells contribute to vascular inflammation but do not differentiate into smooth muscle cell lineages. Circulation. 2009;120:S1090–S1091. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.965202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, Aikawa E, Stangenberg L, Wurdinger T, Figueiredo JL, Libby P, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3037–3047. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.