Abstract

Successful adaptation of in vitro optimized polymeric gene delivery systems for in vivo use remains a significant challenge. Most in vivo applications require particles that are sterically stabilized but doing so significantly compromises transfection efficiency of materials shown to be effective in vitro. In this communication, we present a multi-functional well-defined block copolymer that forms particles with the following properties: cell targeting, reversible shielding, endosomal release, and DNA condensation. We show that targeted and stabilized particles retain transfection efficiencies comparable to the non-stabilized formulations. The block copolymers are synthesized using a novel, double-head agent (CPADB-SS-iBuBr) that combines a RAFT CTA and an ATRP initiator through a disulfide linkage. Using this double-head agent, a well-defined cationic block copolymer P(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50 containing a hydrophilic oligoethyleneglycol (OEG) block and a tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA)-grafted polycation block was synthesized. This material effectively condenses plasmid DNA into salt-stable particles that deshield under intracellular reducing conditions. In vitro transfection studies showed that the reversibly shielded polyplexes afforded up 10-fold higher transfection efficiencies compared to the analogous stably-shielded polymer in four different mammalian cell lines. To compensate for reduced cell uptake caused by the hydrophilic particle shell, a neuron-targeting peptide was further conjugated to the terminus of theP(OEGMA) block. Transfection of neuron-like, differentiated PC-12 cells demonstrated that combining both targeting and deshielding in stabilized particles yields formulations that are suitable for in vivo delivery without compromising in vitro transfection efficiency. These materials are therefore promising carriers for in vivo gene delivery applications.

Polycations are an attractive class of material for gene delivery because they self-assemble with and condense nucleic acids, can be synthesized at large scale, and offer flexible chemistries for functionalization.1 In the past few decades, many polymer compositions and architectures have been synthesized. In vitro screening of these polymers has yielded many materials that efficiently transfect cultured mammalian cells.2 However, only a small subset of these materials issuitable for in vivo use due to additional extracellular barriers. Polyplexes, complexes of polycations and nucleic acids, are colloids typically unstable in physiological conditions.3 Polyplexes are prone to protein adsorption and aggregation, which can lead to inflammation and mortality. Furthermore, when used in vivo, polyplexes must preferentially transfect the target cell type rather than the vast majority of other cells that are present.

To address the aggregation issue, a hydrophilic polymer shell, such as poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) or N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide (HPMA), is incorporated into most polyplex formulations designed for in vivo use.4 However, polyplexes shielded against protein adsorption and aggregation are also poorly recognized and internalized by cells, thereby compromising transfection efficiencies. Formulations with reversible deshielding properties that are usually triggered by acid conditions (found in tumor microenvironments or in endosomes after cellular uptake) or reducing conditions (found in the cell cytosol) have been investigated and shown to generally be more efficient than formulations with stable polymer shields. Notable examples that have been tested for in vivo delivery are (i) Wagner's ternary complexes containing targeting ligand conjugated to one polycation, PEG conjugated to a second polycation via an acid-labile hydrazone, and plasmids, (ii) Wang's ternary complexes of polyplexes coated with a charge-reversing polymer that deshield in mildly acidic environments, and (iii) Kataoka's block copolymers of PEG and poly[Asp(DET)] that deshield in reducing conditions.5 However, to our knowledge, the reported formulations to date either do not incorporate targeting ability and/or require multiple polymer components in the final structures, complicating scale-up and manufacturing.

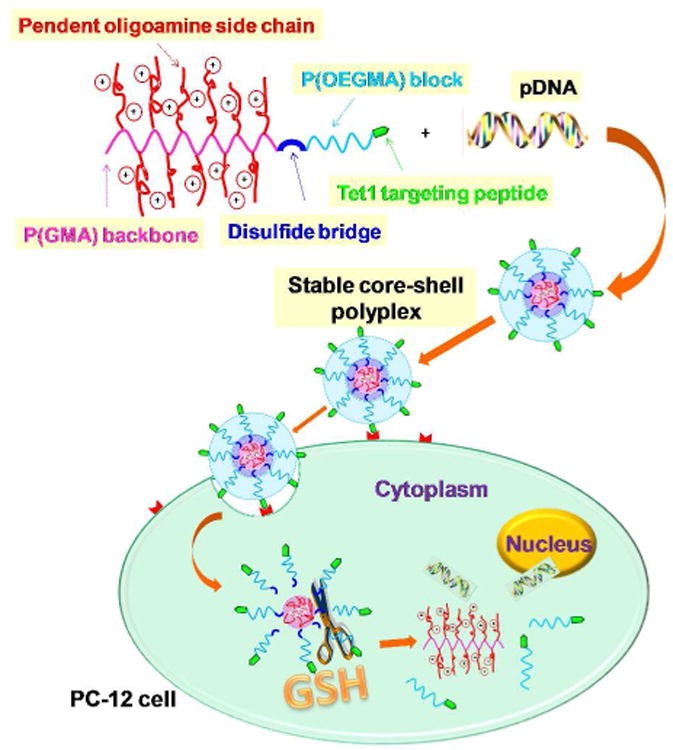

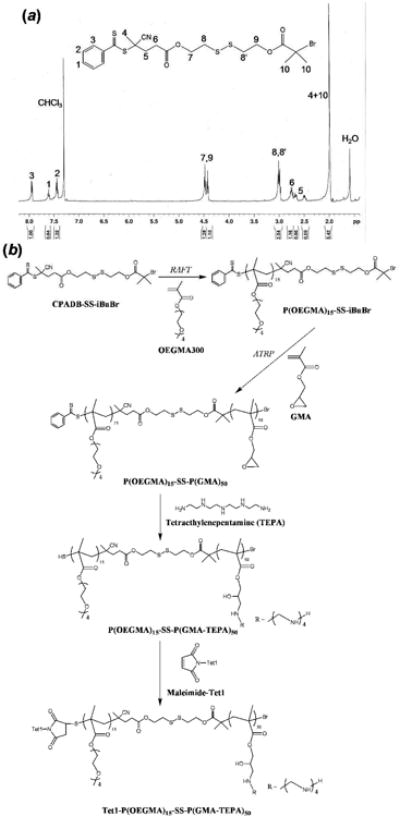

The major advancement reported in this work is the development of a polymeric nucleic acid carrier that incorporates cell targeting, reversible colloidal stability and efficient intracellular delivery into a single well-defined material (Scheme 1). The key enabling technology for this material is a novel, reducible double-head agent consisting of both a reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) agent and an atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) initiator connected by a disulfide bond (Figure 1a). We used this double-head agent to synthesize an optimized reduction-responsive cationic block copolymer P(OEGMA)-SS-P(GMA-TEPA) by a combination of RAFT polymerization of oligo(ethylene glycol) monomethyl ether methacrylate (OEGMA) and ATRP of glycidyl methacrylate (GMA), followed by post-polymerization decoration of reactive epoxy groups in P(GMA) block by tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA) (Figure 1b). We demonstrate that diblock copolymers synthesized using this double-head agent possess several notable qualities. First, they have well-controlled composition with narrowly distributed molecular weight. Second, they can be easily modified with a targeting lig-and at the outer corona. Finally, the “in vivo ready” diblock formulation shows similar transfection efficiency as the in vitro optimized polycation segment due to the reversible shielding combined with targeting ability. The neuron targeting peptide, Tet1-conjugated P(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50 is expected to transfect cells by condensing DNA efficiently to form core-shell type polyplexes with the P(GMA-TEPA)/DNA electrostatic complex building the core and the P(OEGMA) block constructing the shell. Once internalized, the polyplexes become localized within the endocytic vesicles. The protonatable amines in TEPA were included to facilitate endosomal escape through the proton sponge effect6 and glutathiones (GSH) in the intracellular environment are expected to degrade the disulfide links, leading to detachment of the hydrophilic P(OEGMA) coating and release of DNA (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of polymer structure, DNA condensation, cell binding, endocytosis and proposed route for subsequent reduction-triggered intracellular gene release.

Figure 1.

(a) 1H NMR spectrum of the double-head agent (CPADB-SS-iBuBr). (b) Synthesis route of Tet1-P(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50.

The double-head agent CPADB-SS-iBuBr was synthesized by N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) coupling between the RAFT CTA 4-cyanopentanoic acid dithiobenzoate (CPADB)7 and 2-hydroxyethyl-2′-(bromoisobutyryl)ethyl disulfide initiator (OH-SS-iBuBr)8 in the presence of 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP) as a catalyst. After purification by column chromatog-raphy, CPADB-SS-iBuBr was successfully obtained with 43.1% yield (Figure 1a).

The most commonly-used hydrophilic shell employed in polyplex stabilization is PEG due to the facile incorporation of PEG by various methods, such as using a PEG-based macro-initiator5a,9, macro-chain transfer agent (CTA)10 or via coupling reaction11. Coupling reaction through disulfide-thiol exchange usually requires synthesis of both a mercapto-functionalized and a pyridyl disulfide-functionalized polymer,11 therefore involves reaction between large macromolecules as well as extra separation steps to remove the excess homopolymers from desired block copolymers. In addition to PEG, OEGMA and HPMA are two biocompatible, hydrophilic, shell-building units of nano-carriers.12,13 However, there are no published reports thus far on the synthesis of well-defined copolymers containing sheddable OEGMA and HPMA blocks by controlled living radical polymerization (CLRP). Chain extension using different monomers by consecutive CLRP processes always leads to block copolymers with non-degradable C-C links in the block junctions. Recently Oh et al. reported the synthesis of poly(lactide)-SS-polymethacrylate amphiphilic block copolymers with SS linkages positioned at the block junction by ring-opening polymerization (ROP) and ATRP,8 but these methods are limited to the application of cyclic monomers.

The CPADB-SS-iBuBr double-head agent developed herein offers a simple and versatile means to prepare block copolymers based on diverse hydrophilic and hydrophobic monomers with cleavable links in the block junctions for various applications. The design principle of the double-head agent is to integrate RAFT and ATRP techniques, taking advantage of their different mechanisms for orthogonal synthetic strategy. The resulting double-head agent was first used as a RAFT CTA to carry out the polymerization of both OEGMA (Mn~300) and HPMA. The RAFT kinetics of OEGMA (Table S1) and HPMA (Table S2) polymerization using CPADB-SS-iBuBr was monitored by 1H NMR and SEC-MALLS. Both monomers were polymerized with first order kinetics (Figure S2a-c) and low PDI (< 1.3), demonstrating excellent synthesis control via RAFT polymerization.

The hydrophilic OEGMA and HPMA blocks were then used as a macroinitiator for ATRP of GMA. To minimize the possibility of concurrent RAFT-ATRP14, GMA, which is polymerized with fast kinetics by ATRP but with slower kinetics by RAFT, was polymerized with short reaction time. We demonstrate by NMR and GPC analysis that polymerization of GMA occurs predominantly by ATRP (see Supporting Information). Block copolymers of P(OEGMA)-SS-P(GMA) were characterized by 1H NMR to verify successful polymerization and to determine the degree of polymerization (DP) (Figure S1b). P(GMA) contains pendant reactive epoxy groups that were further functionalized by TEPA to generate the polycation block. The final diblock copolymer was characterized by 1H NMR (Figure S1c) and SEC-MALLS (Figure S2d). We, in earlier work, optimized the polycation block, screening various oligoamine and lengths of polymer backbone for optimal cell transfection efficiency (data not shown). Based on this initial screen, we identified P(GMA) of DP 50 grafted with TEPA, P(GMA-TEPA)50 (Mn = 22.5 kDa, PDI = 1.11, dn/dc = 0.216) to be the most effective carrier. Its transfection efficiencies were comparable to that of branched poly(ethylenimine) (bPEI, 25 kDa). We then further tested diblocks of P(GMA-TEPA)50 with P(OEGMA) and P(HPMA) of various lengths and identified an optimal material, P(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50 (Mn = 31.5 kDa, dn/dc = 0.202, PDI = 1.29). As a control, the reduction-insensitive P(OEGMA)15-b-P(GMA-TEPA)50 copolymer (Mn= 30.1 kDa, PDI = 1.28, dn/dc = 0.201) was also synthesized by consecutive RAFT polymerizations using CPADB as a CTA. To incorporate cell targeting, we selected the neuron targeting pep-tide Tet1, which we previously have shown to facilitate targeted transfection both in vitro and in vivo when grafted to PEI.15 A N-terminus maleimide-functionalized Tet1 was conjugated by Michael-type addition to the terminal free thiols of P(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50 and P(OEGMA)15-b-P(GMA-TEPA)50 that were generated by aminolysis of the dithioester end group during TEPA functionalization (Scheme 2). Tet1 functionalization efficiency was ∼33%, likely due to competing thiolactone formation16 (see Supporting Information).

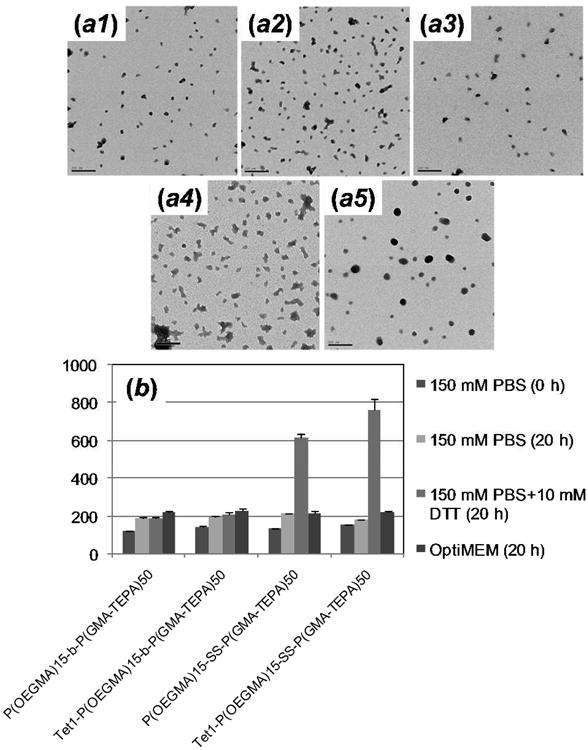

The DNA binding of polymers was investigated by agarose gel retardation assay. The results (Figure S5) indicate that all the polymers exhibit similar DNA condensation above an N/P (amino to phosphate) ratio of 4∼5, and Tet1 peptide conjugation does not significantly affect DNA binding of block copolymers. The morphologies of the five polyplex formulations were visualized by TEM (Figure 2a) at an N/P of 5. All materials condensed plasmid DNA into compact particles with diameter < 50 nm. Polyplexes formed using block copolymers were more compact than those formed by the P(GMA-TEPA)50 homopolymer, and polyplexes containing Tet1 modification were more polydisperse. The uniformity of polyplex morphology and size might be improved in future work by controlling formulation, for example by slow mixing or microfluidics-facilitated mixing as opposed to the bulk mixing used here17.

Figure 2.

(a) TEM images of polyplexes formed by (a1) P(OEGMA)15-b-P(GMA-TEPA)50, (a2) Tet1-P(OEGMA)15-b-P(GMA-TEPA)50, (a3) P(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50, (a4) Tet1-P(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50, and (a5) P(GMA-TEPA)50 at an N/P ratio of 5 (Scale bar: 200 nm). (b) Change in the size of various polyplexes as measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) at 37 °C in the presence of 150 mM PBS, 150 mM PBS + 10 mM DTT, and OptiMEM. All the polyplexes were prepared at an N/P of 5.

Poor salt stability has been a significant obstacle for in vivo application of unshielded polyplexes.18,19 The salt stability of polymer/DNA complexes was studied in both PBS (150 mM, pH 7.4) and Opti-MEM using dynamic light scattering (Figure 2b and Figure S6 for full kinetics). The larger size measured by DLS compared to TEM might be attributed to minority populations of larger particles that skew the average diameters measured by light scattering and also to measurement in salt medium versus water. Only a slight increase in particle size was observed for the polyplexes formed with the block copolymers over a period of 20 h following the addition of physiological levels salt or Opti-MEM media, demonstrating excellent colloidal stability of formed polyplexes. In contrast, polyplexes of P(GMA-TEPA)50 homopolymer formed large aggregates with diameter above 1000 nm within 1 hr under the same conditions (Figure S6c). The overall results confirm that the 4.5 kDa P(OEGMA) block provides sufficient extracellular colloidal stability for P(GMA-TEPA)50 polyplexes. To investigate whether the polyplexes formed using reducible block copolymers would be deshielded in the cytosol to facilitate DNA release in the intracellular reducing environment, the particle sizes of polyplexes in the presence of 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) were monitored over time. Polyplexes of Tet1-P(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50 and P(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50 were found to increase in size due to reduction-triggered deshielding whereas polyplexes formed from the nonreducible polymers were stable in size. Hence, polyplexes of P(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50 may have excellent colloidal stability in the circulation and still be readily destabilized in the cell cytosol, facilitating DNA release.

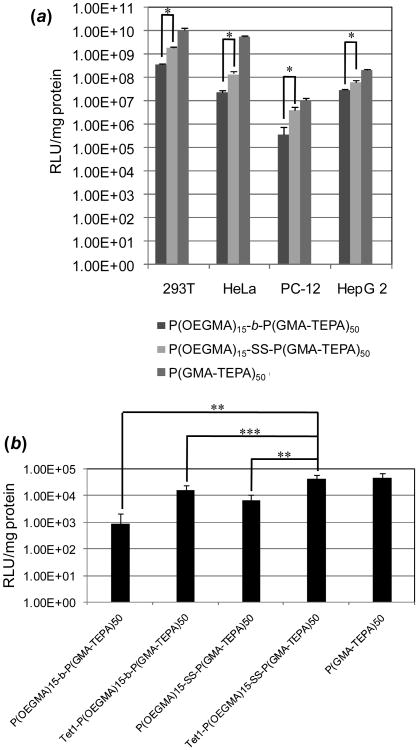

The in vitro transfection efficiency of reducible and non-reducible polyplexes was evaluated in four different cell lines, HeLa, HEK293T, HepG2, and 2-day differentiated PC-12 cells by luciferase assay, using P(GMA-TEPA)50 as a control. Figure 3a summarizes the transfection data for these four different cell lines. The reversibly shielded polyplexes formed by P(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50 mediated significantly higher transfection efficiency in all four cell lines compared to the stably shielded analogue under identical conditions, affording up to 10-times higher transfection efficiency depending on the cell type. The results confirm that the reducible disulfide bond can improve transfection activity. However, the reducible polymers are less efficient than the in vitro optimized homopolycation P(GMA-TEPA)50. This is expected since the hydrophilic shielding layers have been shown to inhibit polyplex uptake.20

Figure 3.

(a) Transfection efficiency of polyplexes based on P(OEGMA)15-b-P(GMA-TEPA)50, P(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50, and P(GMA-TEPA)50 in HEK293T, HeLa, 2-day differentiated PC-12, and HepG2 cells at an N/P ratio of 10. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3;student's t test, *p<0.05). (b) Transfection efficiency of polyplexes formed by P(OEGMA)15-b-P(GMA-TEPA)50, Tet1-P(OEGMA)15-b-P(GMA-TEPA)50, P(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50, Tet1-P(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50 and P(GMA-TEPA)50 in 6-day differentiated PC-12 cellsat an N/P ratio of 5. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6; student's t test,**p< 0.01, ***p< 0.02).

To address decreased polyplex uptake, the targeted transfection efficacy of Tet1-conjugated polyplexes was further assessed in 6-day differentiated PC-12 cells. Differentiated PC-12 cells display a neuron-like phenotype that includes increased binding of the Tet1 peptide.15b The results (Figure 3b) clearly show that conjugation of the Tet1 targeting peptide significantly enhanced transfection compared to corresponding polymer lacking Tet1. Of all the block copolymers, the Tet1-(OEGMA)15-SS-P(GMA-TEPA)50 displays the highest transfection efficacy. Its transfection efficacy is 50-fold higher than non-reducible, non-targeted complexes, 6.1-fold higher than non-targeted, reducible complexes and 2.6-fold higher than non-reducible targeted complexes. Most importantly, polyplexes that include both targeting ligand and releasable shielding coronas transfect target cells with similar efficiencies as the homopolycation.

In summary, we have successfully developed a versatile method for preparing functionalizable reduction-sensitive block copolymers by integrated RAFT and ATRP techniques using a novel, reducible double-head agent. Here, we prepared a neuron-targeted copolymer for nucleic acid delivery applications. We further showed that the resulting materials form particles that are salt stable but due to the combined properties of targeting and shielding still retain high transfection efficiencies comparable to the analogous homopolycation vectors for targeted gene delivery. The approach developed herein provides a versatile means for preparing various types of multifunctional drug and gene delivery vehicles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH 1R01NS064404. D.S-H.C. was supported by an NIH training grant (T32CA138312). We thank Julie Shi and Selvi Srinivasan for technical help and scientific discussion.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: Experimental details, synthesis and characterization of polymers, detailed analysis for concurrent RAFT-ATRP, Table S1-S3, Figure S1-S6. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Pack DW, Hoffman AS, Pun S, Stayton PS. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nrd1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Anderson DG, Lynn DM, Langer R. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:3153–3158. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) De Smedt SC, Demeester J, Hennink WE. Pharm Res. 2000;17:113–126. doi: 10.1023/a:1007548826495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gabrielson NP, Lu H, Yin LC, Li D, Wang F, Cheng JJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:1143–1147. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Haensler J, Szoka FC. Bioconjugate Chem. 1993;4:372–379. doi: 10.1021/bc00023a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hwang SJ, Davis ME. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2001;3:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Miyata K, Kakizawa Y, Nishiyama N, Harada A, Yamasaki Y, Koyama H, Kataoka K. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2355–2361. doi: 10.1021/ja0379666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Oupicky D, Ogris M, Howard KA, Dash PR, Ulbrich K, Seymour LW. Molecular Ther. 2002;5:463–472. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Takae S, Miyata K, Oba M, Ishii T, Nishiyama N, Itaka K, Yamasaki Y, Koyama H, Kataoka K. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6001–6009. doi: 10.1021/ja800336v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Walker GF, Fella C, Pelisek J, Fahrmeir J, Boeckle S, Ogris M, Wagner E. Molecular Ther. 2005;11:418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yang XZ, Du JZ, Dou S, Mao CQ, Long HY, Wang J. ACS Nano. 2012;6:771–781. doi: 10.1021/nn204240b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behr JP. Chimia. 1997;51:34–36. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitsukami Y, Donovan MS, Lowe AB, McCormick CL. Macromolecules. 2001;34:2248–2256. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sourkohi BK, Cunningham A, Zhang Q, Oh JK. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:3819–3825. doi: 10.1021/bm2011032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wen HY, Dong HQ, Xie WJ, Li YY, Wang K, Paulettic GM, Shi DL. Chem Commun. 2011;47:3550–3552. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04983b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu CH, Zheng M, Meng FH, Mickler FM, Ruthardt N, Zhu XL, Zhong ZY. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:769–778. doi: 10.1021/bm201693j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Tang LY, Wang YC, Li Y, Du JZ, Wang J. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:1095–1099. doi: 10.1021/bc900144m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang YC, Wang F, Sun TM, Wang J. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011;22:1939–1945. doi: 10.1021/bc200139n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sun HL, Guo BN, Cheng R, Meng FH, Zhong ZY. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6358–6366. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dey S, Kellam B, Alexander MR, Alexander C, Rose FRAJ. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:6883–6890. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talelli M, Rijcken CJF, van Nostrum CF, Storm G, Hennink WE. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2010;62:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Nicolay R, Kwak Y, Matyjaszewski K. Macromolecules. 2008;41:4585–4596. [Google Scholar]; (b) Elsen AM, Nicolay R, Matyjaszewski K. Macromolecules. 2011;44:1752–1754. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kwak YW, Nicolay R, Matyjaszewski K. Aust J Chem. 2009;62:1384–1401. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Kwon EJ, Lasiene J, Jacobson BE, Park IK, Horner PJ, Pun SH. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2417–2424. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Park IK, Lasiene J, Chou SH, Horner PJ, Pun SH. J Gene Med. 2007;9:691–702. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu JT, He JP, Wang XJ, Yang YL. Macromolecules. 2006;39:8616–8624. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho YP, Grigsby CL, Zhao F, Leong KW. Nano Lett. 2011;11:2178–2182. doi: 10.1021/nl200862n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeong JH, Kim SW, Park TG. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32:1239–1274. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaffert D, Wagner E. Gene Ther. 2008;15:1131–1138. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mishra S, Webster P, Davis ME. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83:97–111. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.