Abstract

Background

Expression of active c-Abl in adult mouse forebrain neurons in the AblPP/tTA mice resulted in severe neurodegeneration, particularly in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Neuronal loss was preceded and accompanied by substantial microgliosis and astrocytosis. In contrast, expression of constitutively active Arg (Abl-related gene) in mouse forebrain neurons (ArgPP/tTA mice) caused no detectable neuronal loss or gliosis, although protein expression and kinase activity were at similar levels to those in the AblPP/tTA mice.

Methods

To begin to elucidate the mechanism of c-Abl-induced neuronal loss and gliosis, gene expression analysis of AblPP/tTA mouse forebrain prior to development of overt pathology was performed. Selected results from gene expression studies were validated with quantitative reverse transcription PCR , immunoblotting and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling, and by immunocytochemistry.

Results

Two of the top pathways upregulated in AblPP/tTA mice with c-Abl expression for 2 weeks were cell cycle and interferon signaling. However, only the expression of interferon signaling pathway genes remained elevated at 4 weeks of c-Abl induction. BrdU incorporation studies confirm that, while the cell cycle pathway is upregulated in AblPP/tTA mice at 2 weeks of c-Abl induction, the anatomical localization of the pathway is not consistent with previous pathology seen in the AblPP/tTA mice. Increased expression and activation of STAT1, a known component of interferon signaling and interferon-induced neuronal excitotoxicity, is an early consequence of c-Abl activation in AblPP/tTA mice and occurs in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, the same region that goes on to develop severe neurodegenerative pathology and neuroinflammation. Interestingly, no upregulation of gene expression of interferons themselves was detected.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that the interferon signaling pathway may play a role in the pathologic processes caused by c-Abl expression in neurons, and that the AblPP/tTA mouse may be an excellent model for studying sterile inflammation and the effects of interferon signaling in the brain.

Introduction

The tyrosine kinase c-Abl has been shown to co-localize with tangles, plaques, and granulovacuolar degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1]. The c-Abl kinase also phosphorylates tau, the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and Fe65, an adaptor protein thought to play a role in APP processing [2-6]. The c-Abl tyrosine kinase has been shown to be activated by oxidative stress and treatment with Aβ peptides in neurons in culture [7]. These known activators of c-Abl are associated with aging and AD and, together with data showing c-Abl activation and co-localization with the characteristic lesions of AD, suggest that c-Abl may be activated during aging and neurodegenerative disease. The AblPP/tTA mouse model, which expresses an inducible, constitutively active form of c-Abl under the CamKIIα promoter using the Tet-Off system, was created to investigate the effects of c-Abl expression in adult forebrain neurons. The AblPP/tTA mouse develops progressive neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, indicating that activation of c-Abl alone in adult neurons is sufficient to cause neuronal loss and inflammation [8].

Aberrant cell cycle activation has been shown to occur in neurons in human AD prior to neuronal death [9-13], and cell cycle events have been shown to precede amyloid deposition and microglial activation in several mouse models of AD [14]. Additionally, mice expressing a transgene that forces postmitotic neurons into the cell cycle recapitulate all the major pathological hallmarks of AD – neurodegeneration, neurofibrillary tangles, and amyloid plaques [15]. Chronic neuroinflammation and upregulation of a multitude of cytokines has been shown to occur in AD [16-26]. Others have suggested that stress/death signals produced by neurons may be the impetus for chronic inflammation in the brain [19,27].

Previously, the pathways that might be induced by c-Abl activity in neurons were unknown. In an effort to elucidate these pathways, we performed gene expression analysis on the forebrains of young AblPP/tTA mice at 2 or 4 weeks offf doxycycline. The expression of thousands of genes was altered in the AblPP/tTA mouse brain, and we chose to focus on two of the top pathways found to be upregulated in the AblPP/tTA mouse: cell cycle and interferon signaling. We show the anatomic location of the induction of cell cycle and interferon stimulated genes in the AblPP/tTA mouse brain, and that changes in interferon-stimulated gene expression occurred in neurons and co-localized in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, which was previously shown to develop severe neuronal loss and neuroinflammation. These data suggest that c-Abl expression in neurons can stimulate interferon signaling in the brain, and that this pathway may play a role in stimulating gliosis and promoting neuronal loss.

Materials and methods

Mice

Cohorts of five to six AblPP/tTA mice [8] and five to six wild-type littermates were used. Additional control mice carried either the CamKII-tTA gene alone or the c-Abl transgene alone. There was no elevation of c-Abl activity in these single transgenic mice. All mice were kept on a diet containing 200 mg/kg doxycycline (Bio-Serv Frenchtown, NJ 08825) throughout breeding, pregnancy, and weaning. Animals were housed in a facility with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and were provided with free access to water and food at all times. Mice were taken off doxycycline at approximately 4 weeks of age in order to induce c-Abl expression. Mice were euthanized with isofluorane and decapitated. Brains were hemisected sagitally. For all experiments, one half of the forebrain (randomly selected) was homogenized and frozen, while the other half was used for microarray analysis, quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qPCR), or immunohistochemistry.

Gene expression analysis

Cohorts of six AblPP/tTA, six wild-type littermates, six c-Abl, and six CamKII-tTA mice at 2 or 4 weeks off doxycycline were used for gene expression analysis. The forebrain of one hemisphere was dissected away from hindbrain and frozen at −80°C prior to RNA extraction. Total RNA from mouse brain was extracted using standard protocols [28]. Total RNA was extracted with an RNeasy kit Valencia, CA 91355 , and RNA was measured for quality using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Reverse transcription was performed using an ArrayScriptTM reverse transcriptase and T7-Oligo (dT)24 primers, followed by second-strand synthesis to generate double-stranded cDNA. The cDNA was converted to biotin-labeled cRNA (TotalprepTM RNA Labeling Kit, Ambion), then hybridized to the microarray platform. Mouse WG-6 Expression BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with 45,281 probes was the microarray platform used. Microarrays were utilized according to the manufacturer’s guidelines (Illumina).

Data was analyzed using the BeadStudio software (Illumina) and BRB Array Tools 3.8, a statistical software package designed for microarray analysis developed by the National Institutes of Health (linus.nci.nih.gov/BRB-ArrayTools.html). Expression differences were considered statistically significant if their P values were less than 0.001 using an F-test. Ingenuity Pathways Analysis application was used to determine which biological pathways were most upregulated in the AblPP/tTA mouse based on statistically significant changes in gene expression. The online database Interferome [29] was used to identify interferon signaling genes.

Quantitative PCR

qPCR was performed according to standard protocols [30]. Briefly, total RNA extraction was performed using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) on hippocampus or cortex of cohorts of five AblPP/tTA mice and five wild-type controls at 2 weeks off doxycyline and 4 weeks off doxycycline according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was measured for quality using a NanoDrop. A SYBRGreen PCR mix was used to conduct qPCR with the ABI Prism 7900HT (Applied Biosystems). β-actin was used as an internal control, and each assay was performed in triplicate. Primers used for qPCR are listed in Table 1. The median value of the replicates for each sample was calculated and expressed as the cycle threshold (CT). ΔCT was calculated as CT of β-actin minus the CT of the gene of interest in each sample. The relative amount of target gene expression in each sample was calculated as 2ΔCT, and fold change was calculated by dividing 2ΔCT of the gene of interest by 2ΔCT of the gene in the control sample.

Table 1.

Antibodies (IHC = immunohistochemistry, IHC-P = immunohistochemistry, paraffin sections; WB = immunoblot)

| Epitope | Antibody | Application | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| BrdU |

1170376 |

IHC-P, 1:400 |

Roche |

| Cyclin B1 |

4135 |

WB, 1:1000 |

Cell Signaling Technology |

| Cyclin D1 |

2926 |

WB, 1:1000 |

Cell Signaling Technology |

| Cdk4 |

2906 |

WB, 1:1000 |

Cell Signaling Technology |

| Cdk2 |

2546 |

WB, 1:1000 |

Cell Signaling Technology |

| Polo-like kinase 1 |

05-844 |

WB, 1:1000 |

Millipore |

| Stat1 |

9172S |

WB, 1:1000 |

Cell Signaling Technology |

| IHC, 1:500 |

|

||

| Stat1 pY701 |

9167S |

WB, 1:1000 |

Cell Signaling Technology |

| IHC, 1:250 |

|

||

| Stat1 pS727 | 9177 s | WB, 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology |

BrdU, bromodeoxyuridine.

Antibodies

Antibodies used for immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers

| Gene | Primer sequences | Source |

|---|---|---|

| IFNα |

F: GGATGTGACCTTCCTCAGACTC |

OriGene |

| R: ACCTTCTCCTGCGGGAATCCAA | ||

| IFNβ |

F: CAGCTCCAAGAAAGGACGAAC |

qPrimerDepot |

| R: GGCAGTGTAACTCTTCTGCAT | ||

| IFNγ |

F: GCGGCCTAGCTCTGAGACAA |

Primer3 |

| R: GACTGTGCCGTGGCAGTAAC | ||

| IL-6 |

F : ATGGATGCTACCAAACTGGAT |

RTPrimerDB |

| R : TGAAGGACTCTGGCTTTGTCT | ||

| IP10 |

F : TCCTTGTCCTCCCTAGCTCA |

RTPrimerDB |

| R : ATAACCCCTTGGGAAGATGG | ||

| IFIT3 |

F: GCTCAGGCTTACGTTGACAAGG |

OriGene |

| R: CTTTAGGCGTGTCCATCCTTCC | ||

| IRF1 |

F: TCCAAGTCCAGCCGAGACACTA |

OriGene |

| R: ACTGCTGTGGTCATCAGGTAGG | ||

| Isg15 |

F: CATCCTGGTGAGGAACGAAAGG |

OriGene |

| R: CTCAGCCAGAACTGGTCTTCGT | ||

| PSMB8 |

F: CCTTACCTGCTTGGCACCATGT |

OriGene |

| R: TTGGATGCTGCAGACACGGAGA | ||

| Stat1 |

F: GCCTCTCATTGTCACCGAAGAAC |

OriGene |

| R: TGGCTGACGTTGGAGATCACCA | ||

| β-actin |

F: TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAG |

Primer3 |

| R: GGATGCAGGGATGATGTTC |

Western blotting

Forebrain homogenates of AblPP/tTA mice and wild-type controls were used. Forebrain samples were homogenized in homogenization buffer (TBS with 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 2 mM EGTA) with complete Mini protease inhibitors (Roche), frozen at −80°C, thawed, and spun at 14,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. Supernatants were analyzed in all experiments by immunoblotting using SDS-PAGE, according to standard protocols. Protein concentrations were normalized prior to use and all western blots were normalized to β-actin loading controls.

Bromodeoxyuridine labeling

Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), 0.5 mg/ml, was administered to cohorts of three AblPP/tTA mice and three wild-type controls in drinking water for 5 days. Mice were euthanized immediately or allowed to age for 4 weeks. For detection of BrdU incorporation, one hemisphere of the brain was fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned in 5 μm increments. After rehydration, sections were steamed in 10 mM citrate buffer for 20 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2 for 10 minutes at room temperature. Sections were then treated with 3 N HCl for 30 minutes at room temperature and blocked in 5% goat serum/2% BSA for 1 hour. Primary antibody (anti-BrdU; Roche) was diluted in blocking solution and sections were incubated overnight at 4°C. Biotinylated secondary antibody was applied for 2 hours at room temperature, followed by streptavidin-HRP for 1 hour at room temperature. A solution of 20% Superblock (ThermoScientific) in TBS + 0.05% Triton X100 was used as a diluent for the secondary antibody and streptavidin-HRP. Staining was visualized with diaminobenzidine.

Immunohistochemistry

Hemisected brains were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde and cut sagitally into 50 μm sections using a vibratome. Standard immunohistochemistry protocols were used. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked using 3% H2O2 in 0.25% TritonX 100 in TBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. Five percent milk/TBS was used as a blocking agent and primary antibody diluent. Sections were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated in primary antibody at 4°C overnight. After washing, biotinylated secondary antibody was applied for 2 hours at room temperature. Washes were repeated, and sections were incubated with Streptavidin-HRP for 1 hour at room temperature. A solution of 20% Superblock (Thermoscientific, Rockford, IL 61101) in TBS + 0.05% Triton X100 was used as a diluent for the secondary antibody and streptavidin-HRP. Staining was visualized with diaminobenzidine.

Immunofluorescence

Endogenous peroxidase activity in vibratome sections of AblPP/tTA and wild-type control mouse brains was blocked by 3% H2O2 in 0.25% TritonX 100 in TBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. Blocking solution and primary antibody diluent was 5% milk. Sections were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated in primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Biotinylated or fluorescently conjugated secondary antibody in 20% Superblock (ThermoScientific) in TBS + 0.05% TritonX100 was applied for 2 hours at room temperature. Sections were washed and incubated in Alexafluor conjugated streptavidin for 1 hour at room temperature and mounted on microscope slides. Secondary antibodies and streptavidin-HRP were diluted in 20% Superblock (ThermoScientific) in TBS + 0.05% TritonX100. Sections were incubated in 0.3% Sudan Black in 70% EtOH for 10 minutes at room temperature. Finally, slides were cover-slipped using Prolong® Gold anti-fade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen). A Leica SP2 Scanning Laser Confocal Microscope was used to visualize fluorescence.

Results

Identification of two pathways induced by c-Abl activation in mouse forebrain

More than 6,000 genes were found to have significant changes in expression in the AblPP/tTA mice at 2 weeks off doxycyline versus wild-type controls, and more than 2,000 genes were found to have significant changes in expression in AblPP/tTA mice at 4 weeks off doxycyline. We used Ingenuity Pathways Analysis to determine the top pathways upregulated in AblPP/tTA mice versus wild-type mice at 2 and 4 weeks off doxycyline. Two of the top pathways that were shown to be upregulated in forebrains of AblPP/tTA mice were cell cycle and interferon signaling.

Cell cycle activation in the AblPP/tTA mouse

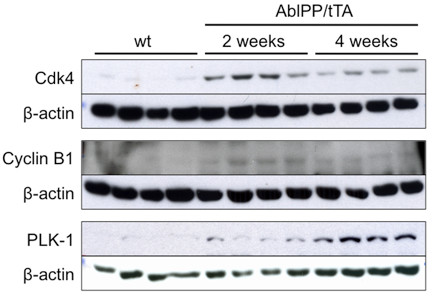

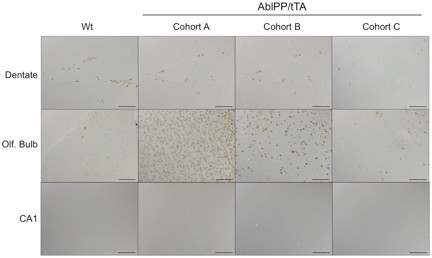

Genes in the cell cycle pathway were strongly upregulated in AblPP/tTA mouse forebrain at 2 weeks off doxycyline, but no significant upregulation was present for any of the cell cycle-related genes at 4 weeks off doxycyline. Fold-change values of cell cycle genes in AblPP/tTA mice at 2 weeks off doxycycline are listed in Table 3. On immunoblot analysis, increases in polo-like kinase 1 (PLK-1), cyclin B1, and CDK 4 protein levels in forebrain homogenates at 2 weeks off doxycyline are apparent; however, levels of CDK 4 and cyclin B1 decrease at 4 weeks off doxycyline (Figure 1). Increases in PLK1 were evident on immunoblots at 4 weeks off doxicycline, but mRNA levels were not significantly elevated at this time point, as stated above. No changes in cyclin D1 or CDK 2 protein levels were observed (data not shown). Because immunoblot analysis could only be performed on whole forebrain homogenate, BrdU incorporation studies were undertaken in order to pinpoint which anatomical regions of the forebrain were experiencing cell cycle activation. Transgenic mice and controls were separated into three groups. Cohort A was administered BrdU for 5 days prior to euthanization at 2 weeks off doxycyline, cohort B was administered BrdU for 5 days prior to euthanization at 4 weeks off doxycyline, and cohort C was administered BrdU for 5 days at the same time off doxycyline as cohort A (beginning at about 1 week off doxycyline until 2 weeks off doxycyline) but allowed to age to 6 weeks off doxycyline. Surprisingly, no animals exhibited BrdU incorporation in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, where obvious neuronal loss occurs in AblPP/tTA mice. However, extensive labeling of the olfactory bulb occurred in mice in cohort A, with somewhat less labeling in cohort B, and the least amount of labeling occurred in cohort C (Figure 2). These results indicated that DNA replication, indicating cell cycle activation, is a very early and transient event in AblPP/tTA mice and seems to be limited to the olfactory bulb. The lack of BrdU labeling in cohort C indicates that the cells that undergo DNA replication in the early stages of c-Abl activation are lost with time. However, there does not appear to be an increase in DNA replication or expression of cell cycle proteins in pyramidal neurons in the CA1, as no cells in this region were found to be positive for BrdU, indicating that a separate process may be at work in that population of neurons.

Table 3.

Cell cycle-related genes induced in AblPP/tTA mice at 2 weeks off doxycycline

| Fold-change | Unique ID | GeneBank Accession | Gene symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.13 |

7200044 |

NM_007631 |

Ccnd1 |

Mus musculus cyclin D1 (Ccnd1), mRNA. |

| 5.04 |

5690441 |

NM_007631 |

Ccnd1 |

Mus musculus cyclin D1 (Ccnd1), mRNA. |

| 4.34 |

20364 |

NM_007631 |

Ccnd1 |

Mus musculus cyclin D1 (Ccnd1), mRNA. |

| 4.03 |

670739 |

NM_175659 |

Hist1h2ah |

Mus musculus histone cluster 1, H2ah (Hist1h2ah), mRNA. |

| 4.03 |

3130609 |

NM_178183 |

Hist1h2ak |

Mus musculus histone cluster 1, H2ak (Hist1h2ak), mRNA. |

| 3.85 |

3520717 |

NM_178188 |

Hist1h2ad |

Mus musculus histone cluster 1, H2ad (Hist1h2ad), mRNA. |

| 3.85 |

1470341 |

NM_175659 |

Hist1h2ah |

Mus musculus histone cluster 1, H2ah (Hist1h2ah), mRNA. |

| 3.59 |

5490193 |

NM_178182 |

Hist1h2ai |

Mus musculus histone cluster 1, H2ai (Hist1h2ai), mRNA. |

| 3.58 |

4250711 |

NM_175661 |

Hist1h2af |

Mus musculus histone cluster 1, H2af (Hist1h2af), mRNA. |

| 3.46 |

6510253 |

NM_178185 |

Hist1h2ao |

Mus musculus histone cluster 1, H2ao (Hist1h2ao), mRNA. |

| 3.28 |

7200519 |

NM_007681 |

Cenpa |

Mus musculus centromere protein A (Cenpa), mRNA. |

| 3.27 |

7160253 |

NM_178188 |

Hist1h2ad |

Mus musculus histone cluster 1, H2ad (Hist1h2ad), mRNA. |

| 3.1 |

4610129 |

NM_178184 |

Hist1h2an |

Mus musculus histone cluster 1, H2an (Hist1h2an), mRNA. |

| 2.94 |

1580088 |

NM_009829 |

Ccnd2 |

Mus musculus cyclin D2 (Ccnd2), mRNA. |

| 2.9 |

1260324 |

NM_009829 |

Ccnd2 |

Mus musculus cyclin D2 (Ccnd2), mRNA. |

| 2.77 |

6060379 |

NM_007659 |

Cdc2a |

Mus musculus cell division cycle 2 homolog A (S. pombe) (Cdc2a), mRNA. |

| 2.77 |

1050170 |

NM_013538 |

Cdca3 |

Mus musculus cell division cycle associated 3 (Cdca3), mRNA. |

| 2.76 |

4610722 |

NM_023223 |

Cdc20 |

Mus musculus cell division cycle 20 homolog (S. cerevisiae) (Cdc20), mRNA. |

| 2.61 |

6450634 |

NM_026560 |

Cdca8 |

Mus musculus cell division cycle associated 8 (Cdca8), mRNA. |

| 2.52 |

2190164 |

NM_172301 |

Ccnb1 |

Mus musculus cyclin B1 (Ccnb1), mRNA. |

| 2.51 |

4250403 |

NM_011623 |

Top2a |

Mus musculus topoisomerase (DNA) II alpha (Top2a), mRNA. |

| 2.41 |

4390228 |

NM_023223 |

Cdc20 |

Mus musculus cell division cycle 20 homolog (S. cerevisiae) (Cdc20), mRNA. |

| 2.34 |

630446 |

NM_183417 |

Cdk2 |

Mus musculus cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2), transcript variant 1, mRNA. |

| 2.33 |

520427 |

NM_011121 |

Plk1 |

Mus musculus polo-like kinase 1 (Drosophila) (Plk1), mRNA. |

| 2.15 |

4570088 |

NM_023223 |

Cdc20 |

Mus musculus cell division cycle 20 homolog (S. cerevisiae) (Cdc20), mRNA. |

| 2.12 |

1110390 |

NM_178182 |

Hist1h2ai |

Mus musculus histone cluster 1, H2ai (Hist1h2ai), mRNA. |

| 2.09 |

5820653 |

NM_175661 |

Hist1h2af |

Mus musculus histone cluster 1, H2af (Hist1h2af), mRNA. |

| 2.05 |

70546 |

NM_178186 |

Hist1h2ag |

Mus musculus histone cluster 1, H2ag (Hist1h2ag), mRNA. |

| 2.01 |

7550156 |

NM_172301 |

Ccnb1 |

Mus musculus cyclin B1 (Ccnb1), mRNA. |

| 2.01 |

6860463 |

NM_009870 |

Cdk4 |

Mus musculus cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (Cdk4), mRNA. |

| 1.77 |

1740039 |

NM_016756 |

Cdk2 |

Mus musculus cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2), transcript variant 1, mRNA. |

| 1.69 |

610717 |

NM_007632 |

Ccnd3 |

Mus musculus cyclin D3 (Ccnd3), transcript variant 1, mRNA. |

| 1.61 |

1820274 |

NM_175384 |

Cdca2 |

Mus musculus cell division cycle associated 2 (Cdca2), mRNA. |

| 1.6 |

1500446 |

NM_026560 |

Cdca8 |

Mus musculus cell division cycle associated 8 (Cdca8), mRNA. |

| 1.58 |

4920148 |

NM_013538 |

Cdca3 |

Mus musculus cell division cycle associated 3 (Cdca3), mRNA. |

| 1.46 |

6770286 |

AK077367 |

Ccnd2 |

Mus musculus cyclin D2 (Ccnd2), mRNA. |

| 1.4 |

770162 |

NM_177733 |

E2f2 |

Mus musculus E2F transcription factor 2 (E2f2), mRNA. |

| 1.37 |

1570754 |

NM_023223 |

Cdc20 |

Mus musculus cell division cycle 20 homolog (S. cerevisiae) (Cdc20), mRNA. |

| 1.33 |

6550164 |

NM_177733 |

E2f2 |

Mus musculus E2F transcription factor 2 (E2f2), mRNA. |

| 1.28 |

2000440 |

NM_183417 |

Cdk2 |

Mus musculus cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2), transcript variant 1, mRNA. |

| 1.26 |

4920468 |

NM_028023 |

Cdca4 |

Mus musculus cell division cycle associated 4 (Cdca4), mRNA. |

| 1.24 |

7160066 |

NM_028023 |

Cdca4 |

Mus musculus cell division cycle associated 4 (Cdca4), mRNA. |

| 1.23 | 3870112 | NM_183417 | Cdk2 | Mus musculus cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2), transcript variant 1, mRNA. |

Figure 1.

Cell cycle activation in the AblPP/tTA mouse. Western blotting of wild-type versus AblPP/tTA mouse forebrain homogenates. Cyclin B1 and Cdk4 levels are elevated in mice expressing consitutively active c-Abl for 2 weeks, but not 4 weeks, consistent with increased mRNA levels (Table 3). Polo-like kinase (PLK1) levels were elevated at 2 and 4 weeks, but mRNA levels were only elevated at 2 weeks.

Figure 2.

Cell cycle activation occurs in the olfactory bulb but not in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in AblPP/tTA mice and decreases with time. Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling of wild-type versus AblPP/tTA mice. Cohort A = BrdU labeling at 2 weeks, euthanized at 2 weeks; Cohort B = BrdU labeling at 4 weeks, euthanized at 4 weeks; Cohort C = BrdU labeling at 2 weeks, euthanized at 6 weeks. Scalebars: Dentate, Olfactory bulb = 400 μm, CA1 = 800 μm.

Interferon signaling pathways in the AblPP/tTA mouse

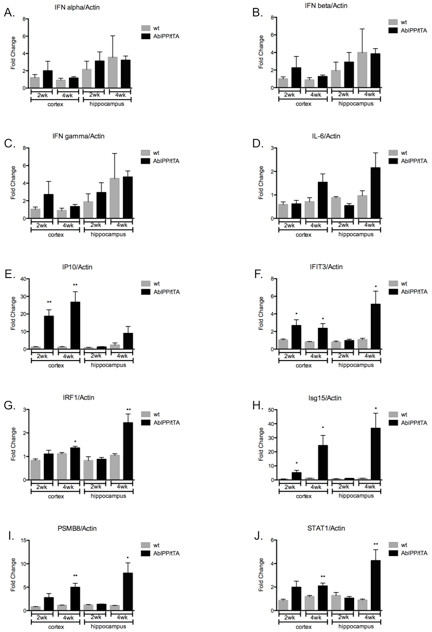

Expression of interferon signaling genes was strongly upregulated in AblPP/tTA mouse forebrain at both 2 and 4 weeks off doxycyline. Table 4 lists fold change values for interferon signaling genes in AblPP/tTA mice. Interestingly, despite the strong induction of genes downstream of interferons α, β, and γ, there were no significant changes in gene expression of interferons themselves. In order to confirm these results, we selected six genes in the interferon signaling pathway and performed qPCR on the hippocampus and cortex of AblPP/tTA mice 2 and 4 weeks off doxycycline. The qPCR analysis revealed that there was strong upregulation of the six genes that were downstream of the interferons, but no significant upregulation of interferons themselves (Figure 3). IP10, IFIT3, IRF1, Isg15, PSMB8, and STAT1 were all significantly upregulated in AblPP/tTA mouse cortex at 4 weeks off doxycyline, and all these genes except IP10 were also significantly upregulated in the hippocampus. Despite the lack of statistical significance, IP10 does trend toward increased levels in the hippocampus at 4 weeks off doxycycline. The qPCR data indicate that the induction of interferon stimulated genes increases with time off doxycyline.

Table 4.

Interferon related genes increased at 2 and 4 weeks off doxicycline

|

Fold Change |

Unique ID | GeneBank Accession | Gene symbol | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 weeks | 4 weeks | ||||

| 9.25 |

9.29 |

460221 |

XM_001472500 |

Isg15 |

PREDICTED: Mus musculus hypothetical protein LOC100038882 (LOC100038882), mRNA. |

| 6.23 |

3.27 |

160463 |

NM_010708 |

Lgals3bp |

Mus musculus lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble, 3 binding protein (Lgals3bp), mRNA. |

| 5.59 |

2.19 |

3840292 |

NM_010509 |

Ifitm3 |

Mus musculus interferon induced transmembrane protein 3 (Ifitm3), mRNA. |

| 5.07 |

3 |

2570095 |

NM_010724 |

Psmb8 |

Mus musculus proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, beta type 8 (large multifunctional peptidase 7) (Psmb8), mRNA. |

| 5.05 |

2.56 |

1400041 |

NM_018734 |

Gbp2 |

Mus musculus guanylate binding protein 2 (Gbp2), mRNA. |

| 5.02 |

4.24 |

1580528 |

NM_011909 |

Usp18 |

Mus musculus ubiquitin specific peptidase 18 (Usp18), mRNA. |

| 4.89 |

3.63 |

7510020 |

NM_010501 |

Ifit3 |

Mus musculus interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3 (Ifit3), mRNA. |

| 4.8 |

3.08 |

6760390 |

NM_010387 |

H2-D1 |

Mus musculus histocompatibility 2, D region locus 1 (H2-D1), mRNA. |

| 4.47 |

4.23 |

4830010 |

NM_011854 |

Oasl2 |

Mus musculus 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase-like 2 (Oasl2), mRNA. |

| 4.13 |

2.96 |

60553 |

NM_018734 |

Gbp3 |

Mus musculus guanylate nucleotide binding protein 3 (Gbp3), mRNA. |

| 3.98 |

3.67 |

5270398 |

NM_008332 |

Ifit2 |

Mus musculus interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2 (Ifit2), mRNA. |

| 3.04 |

1.52 |

3940639 |

NM_027450 |

Glipr2 |

Mus musculus GLI pathogenesis-related 2 (Glipr2), mRNA. |

| 2.96 |

1.62 |

4830543 |

NM_023065 |

Ifi27 |

Mus musculus interferon, alpha-inducible protein 27 (Ifi27), mRNA. |

| 2.93 |

1.45 |

430167 |

NM_008534 |

Ly86 |

Mus musculus lymphocyte antigen 86 (Ly86), mRNA. |

| 2.62 |

1.63 |

3140209 |

NM_013655 |

Cxcl10 |

Mus musculus chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 (Cxcl10), mRNA. |

| 2.59 |

1.67 |

2230386 |

NM_008348 |

Iigp2 |

Mus musculus interferon inducible GTPase 2 (Iigp2), mRNA. |

| 2.5 |

1.81 |

830762 |

NM_026030 |

Eif2ak2 |

Mus musculus eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-alpha kinase 2 (Eif2ak2), mRNA. |

| 2.47 |

1.94 |

6660634 |

NM_008390 |

Irf1 |

Mus musculus interferon regulatory factor 1 (Irf1), mRNA. |

| 2.14 |

1.35 |

6660176 |

NM_213659 |

Stat3 |

Mus musculus signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3), transcript variant 1, mRNA. |

| 2.08 |

1.94 |

2000373 |

NM_009825 |

Serping1 |

Mus musculus serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade G, member 1 (Serping1), mRNA. |

| 2.06 |

1.33 |

3780736 |

NM_001001892 |

H2-K1 |

Mus musculus histocompatibility 2, K1, K region (H2-K1), transcript variant 1, mRNA. |

| 1.93 |

1.39 |

130598 |

NM_011852 |

Oas1g |

Mus musculus 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase 1 G (Oas1g), mRNA. |

| 1.9 |

1.49 |

5720255 |

NM_201394 |

Pld4 |

Mus musculus phospholipase D family, member 4 (Pld4), mRNA. |

| 1.86 |

1.43 |

4120014 |

NM_008330 |

Ifi35 |

Mus musculus interferon-induced protein 35 (Ifi35), mRNA. |

| 1.85 |

1.48 |

4150050 |

NM_133779 |

Pigt |

Mus musculus phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis, class T (Pigt), mRNA. XM_922599 |

| 1.84 |

1.87 |

3060482 |

NM_008394 |

Irf9 |

Mus musculus interferon regulatory factor 9 (Irf9), mRNA. |

| 1.81 |

1.29 |

2100484 |

NM_025928 |

Plxnb2 |

PREDICTED: Mus musculus plexin B2, transcript variant 13 (Plxnb2), mRNA. |

| 1.76 |

1.84 |

240725 |

NM_009283 |

Stat1 |

Mus musculus signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (Stat1), mRNA. |

| 1.72 |

2.11 |

520278 |

NM_024263 |

Mx2 |

Mus musculus myxovirus (influenza virus) resistance 2 (Mx2), mRNA. |

| 1.67 |

1.4 |

5870093 |

NM_011530 |

Tap1 |

Mus musculus transporter 1, ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP) (Tap1), mRNA. |

| 1.64 |

1.37 |

6770114 |

NM_001012236 |

Trem2 |

Mus musculus triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (Trem2), mRNA. |

| 1.61 |

1.29 |

3780279 |

NM_026116 |

Bax |

Mus musculus Bcl2-associated X protein (Bax), mRNA. |

| 1.55 |

1.32 |

5130139 |

NM_009369 |

Tgfb1 |

Mus musculus transforming growth factor, beta 1 (Tgfb1), mRNA. |

| 1.55 |

1.22 |

1090139 |

NM_008332 |

Ifi47 |

Mus musculus interferon gamma inducible protein 47 (Ifi47), mRNA. |

| 1.53 |

1.3 |

3060450 |

NM_011854 |

Oas2 |

Mus musculus 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase 2 (Oas2), mRNA. |

| 1.49 |

1.29 |

6590653 |

NM_008320 |

Irf7 |

Mus musculus interferon regulatory factor 7 (Irf7), mRNA. |

| 1.47 |

1.49 |

5870398 |

NM_011970 |

Psmb10 |

Mus musculus proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, beta type 10 (Psmb10), mRNA. |

| 1.45 |

1.25 |

460435 |

NM_016660 |

Hmg20b |

Mus musculus high mobility group 20 B (Hmg20b), mRNA. |

| 1.42 |

1.22 |

290494 |

XM_894155 |

BC004012 |

Mus musculus Nadk NAD kinase, mrNA. |

| 1.4 |

1.42 |

6220594 |

NM_213659 |

Stat2 |

Mus musculus signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 (Stat2), mRNA. |

| 1.4 |

1.37 |

4810072 |

NM_008490 |

Lcat |

Mus musculus lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase (Lcat), mRNA. |

| 1.39 |

1.42 |

2450554 |

NM_011175 |

Lgi4 |

Mus musculus leucine-rich repeat LGI family, member 4 (Lgi4), mRNA. |

| 1.38 |

1.24 |

2480373 |

NM_026836 |

Taf10 |

Mus musculus TAF10 RNA polymerase II, TATA box binding protein (TBP)-associated factor (Taf10), mRNA. |

| 1.33 |

1.39 |

6550376 |

NM_008529 |

Ly6e |

Mus musculus lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus E (Ly6e), mRNA. |

| 1.33 |

1.21 |

540411 |

NM_177663 |

Isg20 |

Mus musculus interferon-stimulated protein (Isg20), mRNA. |

| 1.31 |

1.42 |

7210687 |

NM_007471 |

Apoe |

Mus musculus apolipoprotein E (Apoe), mRNA. |

| 1.26 |

1.22 |

990129 |

NM_026960 |

Grwd1 |

Mus musculus glutamate-rich WD repeat containing 1 (Grwd1), mRNA. |

| 1.24 |

1.19 |

5870255 |

NM_028162 |

Tbc1d10a |

Mus musculus TBC1 domain family, member 10a (Tbc1d10a), mRNA. |

| 1.22 | 1.49 | 4890626 | NM_008879 | Lcn2 | Mus musculus lipocalin 2 (Lcn2), mRNA. |

Figure 3.

Expression of interferon signaling genes is upregulated in AblPP/tTA mice, but expression of interferons themselves are not. Quantitative real-time PCR of AblPP/tTA mouse cortex and hippocampus versus wild-type mouse cortex and hippocampus at 2 and 4 weeks off doxycyline. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

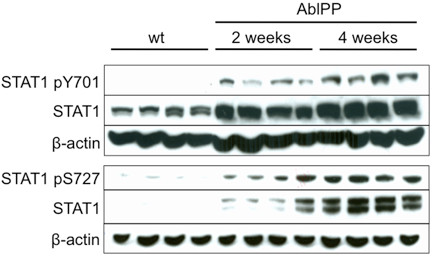

We confirmed that STAT1, a key signaling molecule in the interferon pathway, is upregulated on a protein level in AblPP/tTA mouse forebrain by immunoblotting. Additionally, STAT1 expression is not only upregulated, but the protein itself is activated by phosphorylation at Y701 and Y727 (Figure 4). Phosphorylation of tyrosine 701 on STAT1 activates the protein, and phosphorylation of this site is necessary for STAT1 dimerization and translocation into the nucleus [31]. STAT1 signals remain high and seem to increase at 4 weeks off doxycyline, indicating that the interferon signaling pathway activation in AblPP/tTA mice is most likely not a transient event.

Figure 4.

Levels of activated STAT1 are increased in AblPP/tTA mice 2 and 4 weeks off doxycycline. Western blot membranes were probed with antibodies to STAT1 pY701, STAT pS727, STAT1, and β-actin loading control. STAT1 pY701, STAT1 pS727, and STAT1 total protein levels were elevated in AblPP mice expressing constitutively active c-Abl for 2 and 4 weeks compared with wild-type controls.

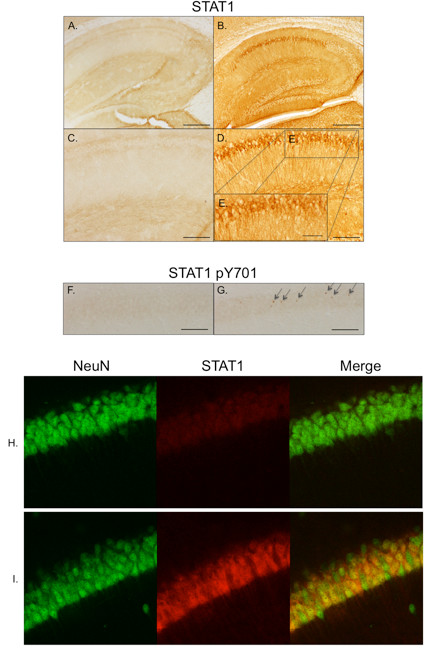

Interferon signaling is upregulated in neurons of the CA1 region of the hippocampus

In order to determine the cell type that demonstrates an increased expression of STAT 1, immunohistochemistry and double-labeling experiments were performed. In Figure 5, we show that STAT1 is elevated in neurons in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in AblPP/tTA mice, and that STAT1 co-localizes with the neuronal marker NeuN. These data indicate that STAT1 expression is induced in neurons themselves. Intriguingly, the STAT1 staining co-localizes to the CA1 region of the hippocampus, which experiences severe neuronal loss in aged AblPP/tTA mice.

Figure 5.

STAT1 expression occurs in neurons of the CA1 region of the hippocampus in AblPP/tTA mice prior to neuronal loss. (A-E) STAT1 immunohistochemistry of the CA1 region of an AblPP/tTA mouse expressing constitutively active c-Abl for 3 weeks (B,D,E) versus wild-type control (A,C). (F,G) STAT1pY701 immunohistochemistry the CA1 region of a wild-type mouse (F) versus an AblPP/tTA mouse 3 weeks off doxycyline (G). Cells positive for STAT1 pY701 are indicated with arrows. (H,I) Double labeling with NeuN (green) and total STAT1 (red) in wild-type (panel H) and AblPP mice expressing constitutively active c-Abl for 2 weeks (panel I). Scalebars: A,B = 2 mm; C,D,F,G = 800 μm; E = 400 μm.

Discussion

It has been shown previously that c-Abl activation in adult neurons leads to neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation [8]. However, the mechanism by which c-Abl activation leads to these consequences remains unknown. In the work presented here, we show a correlation between c-Abl activation and the induction of two cell signaling pathways. First, transient but strong expression of cell cycle related proteins and DNA replication occurs in the olfactory bulb. Second, induction of interferon signaling genes occurs in the hippocampus, and the major signaling molecule of this pathway, STAT1, is upregulated in neurons in the CA1 region.

The first pathway examined was the cell cycle. The data show that expression of cell cycle related proteins and DNA replication does occur in AblPP/tTA mice, indicating that the cell cycle is activated, at least partially through S-phase. However, these findings do not localize to the CA1 region of the hippocampus. This suggests that aberrant cell cycle activation does not play a role in neuronal death observed in pyramidal neurons in CA1 of AblPP/tTA mice. Increased BrdU incorporation occurred mainly in the olfactory bulb, although BrdU-labeled cells were also found along a pathway anatomically consistent with the rostral migratory stream (data not shown). There is abundant expression of AblPP in the olfactory bulb [8].

Interestingly, BrdU labeling occurred in cells in the olfactory bulb when BrdU was administered at 2 weeks off doxycyline and mice were euthanized immediately, but BrdU labeling precipitously decreased when mice were administered BrdU at 2 weeks off doxycyline then aged for a further 4 weeks (Figure 2). Therefore, the cells that undergo DNA replication in the olfactory bulb of AblPP/tTA mice do not appear to survive for an extended period of time. The number of cells labeled in the dentate gyrus of AblPP/tTA mice also appears to decrease. This raises the possibility that c-Abl strongly induces DNA replication and possibly aberrant cell cycle activation at early time points, but that the cells that undergo this process may have impaired survival and decreased ability to replicate DNA as the mice age. BrdU labeling experiments performed on older AblPP/tTA mice support this hypothesis. In mice that were administered BrdU for 5 days prior to euthanization at 11 weeks off doxycyline, no labeling of the dentate gyrus occurred (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

The second pathway that we examined was interferon signaling. Our findings that interferon stimulated genes are induced in the presence of active c-Abl are consistent with previous reports showing that P210 BCR/Abl can induce expression of interferon responsive genes, including OAS1, IFIT1, IFI16, ISGF3G, and STAT1, in U937 cells in culture [32]. Also consistent with other studies, we find no evidence of significant induction of interferons themselves [32]. While other groups have focused on myeloid cells, this is the first evidence that interferon signaling pathways are induced by c-Abl activation in adult neurons in vivo. These data suggest that the AblPP/tTA mouse model will be useful to investigate the role of interferon signaling in neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation.

Given that STAT1, the major signaling molecule downstream of the interferons, was activated in the same anatomical region in which neurodegeneration occurs in AblPP/tTA mice, it is possible that STAT1 activation and interferon signaling play a role in c-Abl induced pathology in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. STAT1 activation has been associated with death in terminally differentiated cells and has been shown to play a role in apoptosis in response to TNFα treatment in cell culture [33]. Ischemia-reperfusion induced death is enhanced by STAT1 in cardiac myocytes, which, like neurons, are terminally differentiated [34,35]. Treatment of mice with paraquat, a toxin that induces selective loss of dopaminergic neurons, resulted in increased expression of STAT1 mRNA in the substantia nigra pars compact in a time course corresponding to dopaminergic neuronal loss [36]. Activated (pY701) STAT1 is upregulated in rat brain during focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion experiments and localizes to the core of lesions, indicating that it may play a role in cell death during ischemia-reperfusion [37].

The role of other interferon signaling genes in neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory diseases is less clear. Interferon signaling has been associated with cell loss, and, while we observe no significant increases in expression of interferons themselves, it is reasonable to assume that activation of downstream signaling molecules could have a similar effect as treatment with interferons themselves. In SHSY5Y cells, interferon β treatment results in apoptosis, and pretreatment of interferon β treated cells with P6, a pan-JAK inhibitor that results in downstream inhibition of STATs, led to decreased caspase 9, 7, and 3 cleavage and decreases in PARP expression, resulting in rescue of the apoptotic phenotype [38]. In primary neuronal cultures, long-term treatment with interferon β led to loss of neuritic processes and increased pY701 STAT1 and caspase 3 levels [38], and interferon γ knockout mice exhibited less neuronal loss in response to paraquat treatment, suggesting that interferon γ signaling may play a role in paraquat-induced neuronal loss [36]. Interferon regulatory factor 1 is thought to play a role in neuronal death in response to ischemia [39]. However, interferon regulatory factors 3 and 7 have been shown to be necessary for neuroprotection in multiple preconditioning paradigms for ischemia reperfusion injury [40].

While the precise role of cell cycle activation and interferon signaling in response to c-Abl activation in neurons remains unclear, we have demonstrated that c-Abl activation leads to an early, transient induction of cell cycle activation in the olfactory bulb and rostral migratory stream and to induction of interferon stimulated genes without (or prior to) induction of interferon expression. One interpretation of these data is that the cell cycle activation observed may be due to a transient stimulation of neurogenesis, although further studies would be necessary to confirm this hypothesis. Interestingly, there is evidence that interferon signaling downstream of c-Abl may have a role to play in stimulation of neurogenesis, as interferon treatment in 3xTg mice lead to increased neurogenesis in addition to increased severity of amyloid pathology and inflammation [41].

The localization of STAT1 activation in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, where severe neuronal loss and neuroinflammation occurs in aged AblPP/tTA mice, suggests that c-Abl induced expression of interferon signaling genes may play a role in the development of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration observed in these mice. Further studies are necessary to determine whether STAT1 and other interferon signaling genes play a causative or protective role in neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation in AblPP/tTA mice. However, these data show a correlation between sites of neurodegeneration and gliosis and interferon signaling. Overall, these data show that the AblPP/tTA mouse may be an excellent model of sterile neuroinflammation in the context of neurodegeneration and could be used to elucidate the role of interferon signaling in neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative disorders.

Abbreviations

AD: Alzheimer’s disease; APP: amyloid precursor protein; Arg: Abl-related gene; BrdU: bromodeoxyuridine; PLK-1: polo-like kinase 1; qPCR: Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SD and PD designed these studies, and carried out all animal work and protein analyses. HS and SCL performed and analyzed the qPCR data. CG and SC performed and analyzed the microarray studies, and CA performed the immunohistochemisty. SD and PD wrote the manuscript, and all authors read and approved the final version.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1.Neurogenesis is apparently lost in AblPP/tTA mice with age. Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling of the dentate gyrus of wild-type versus AblPP/tTA mice at 11 weeks off doxycyline. Scalebars = 400 μm. The localization of BrdU labeled cells is consistent with the distribution of neuroblasts.

Contributor Information

Sarah D Schlatterer, Email: sarah.schlatterer@med.einstein.yu.edu.

Hyeon-sook Suh, Email: hyeon-sook.suh@einstein.yu.edu.

Concepcion Conejero-Goldberg, Email: CGoldber@NSHS.edu.

Shufen Chen, Email: schen3@nshs.edu.

Christopher M Acker, Email: Christopher.acker@einstein.yu.edu.

Sunhee C Lee, Email: sunhee.lee@einstein.yu.edu.

Peter Davies, Email: pdavies@nshs.edu.

References

- Jing Z, Caltagarone J, Bowser R. Altered subcellular distribution of c-Abl in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17:409–422. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkinton MS, Standen CL, Lau KF, Kesavapany S, Byers HL, Ward M, McLoughlin DM, Miller CC. The c-Abl tyrosine kinase phosphorylates the Fe65 adaptor protein to stimulate Fe65/amyloid precursor protein nuclear signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22084–22091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez MC, Vargas LM, Inestrosa NC, Alvarez AR. c-Abl modulates AICD dependent cellular responses: transcriptional induction and apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220:136–143. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambrano N, Bruni P, Minopoli G, Mosca R, Molino D, Russo C, Schettini G, Sudol M, Russo T. The beta-amyloid precursor protein APP is tyrosine-phosphorylated in cells expressing a constitutively active form of the Abl protoncogene. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19787–19792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100792200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay MA, Acker CM, Davies P. Tau phosphorylated at tyrosine 394 is found in Alzheimer’s disease tangles and can be a product of the Abl-related kinase, Arg. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:721–733. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkinderen P, Scales TM, Hanger DP, Leung KY, Byers HL, Ward MA, Lenz C, Price C, Bird IN, Perera T, Kellie S, Williamson R, Noble W, Van Etten RA, Leroy K, Brion JP, Reynolds CH, Anderton BH. Tyrosine 394 is phosphorylated in Alzheimer’s paired helical filament tau and in fetal tau with c-Abl as the candidate tyrosine kinase. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6584–6593. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1487-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez AR, Sandoval PC, Leal NR, Castro PU, Kosik KS. Activation of the neuronal c-Abl tyrosine kinase by amyloid-beta-peptide and reactive oxygen species. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;17:326–336. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlatterer SD, Tremblay MA, Acker CM, Davies P. Neuronal c-Abl overexpression leads to neuronal loss and neuroinflammation in the mouse forebrain. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;25:119–133. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-102025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent I, Jicha G, Rosado M, Dickson DW. Aberrant expression of mitotic cdc2/cyclin B1 kinase in degenerating neurons of Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3588–3598. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03588.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busser J, Geldmacher DS, Herrup K. Ectopic cell cycle proteins predict the sites of neuronal cell death in Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2801–2807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02801.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent I, Rosado M, Davies P. Mitotic mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease? J Cell Biol. 1996;132:413–425. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Geldmacher DS, Herrup K. DNA replication precedes neuronal cell death in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2661–2668. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02661.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Mufson EJ, Herrup K. Neuronal cell death is preceded by cell cycle events at all stages of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2557–2563. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02557.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Varvel NH, Lamb BT, Herrup K. Ectopic cell cycle events link human Alzheimer’s disease and amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse models. J Neurosci. 2006;26:775–784. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3707-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KH, Hallows JL, Chakrabarty P, Davies P, Vincent I. Conditional neuronal simian virus 40 T antigen expression induces Alzheimer-like tau and amyloid pathology in mice. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2969–2978. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0186-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, McGeer EG. The inflammatory response system of brain: implications for therapy of Alzheimer and other neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1995;21:195–218. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(95)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, Bradt B, Bauer J, Cole GM, Cooper NR, Eikelenboom P, Emmerling M, Fiebich BL, Finch CE, Frautschy S, Griffin WS, Hampel H, Hull M, Landreth G, Lue L, Mrak R, Mackenzie IR, McGeer PL, O’Banion MK, Pachter J, Pasinetti G, Plata-Salaman C, Rogers J, Rydel R, Shen Y, Streit W, Strohmeyer R, Tooyoma I. et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:383–421. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00124-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger ME, Landreth GE. Inflammation, apoptosis, and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscientist. 2002;8:276–283. doi: 10.1177/1073858402008003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T, Mucke L. Inflammation in neurodegenerative disease–a double-edged sword. Neuron. 2002;35:419–432. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00794-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease: driving force, bystander or beneficial response? Nat Med. 2006;12:1005–1015. doi: 10.1038/nm1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass CK, Saijo K, Winner B, Marchetto MC, Gage FH. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell. 2010;140:918–934. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WS, Sheng JG, Royston MC, Gentleman SM, McKenzie JE, Graham DI, Roberts GW, Mrak RE. Glial-neuronal interactions in Alzheimer’s disease: the potential role of a ‘cytokine cycle’ in disease progression. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:65–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukiw WJ. Gene expression profiling in fetal, aged, and Alzheimer hippocampus: a continuum of stress-related signaling. Neurochem Res. 2004;29:1287–1297. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000023615.89699.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WS, Sheng JG, Roberts GW, Mrak RE. Interleukin-1 expression in different plaque types in Alzheimer’s disease: significance in plaque evolution. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;54:276–281. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199503000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng JG, Mrak RE, Griffin WS. Glial-neuronal interactions in Alzheimer disease: progressive association of IL-1alpha + microglia and S100beta + astrocytes with neurofibrillary tangle stages. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:285–290. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199703000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarkowski E, Blennow K, Wallin A, Tarkowski A. Intracerebral production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, a local neuroprotective agent, in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:223–230. doi: 10.1023/A:1020568013953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldskogius H, Liu L, Svensson M. Glial responses to synaptic damage and plasticity. J Neurosci Res. 1999;58:33–41. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19991001)58:1<33::AID-JNR5>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conejero-Goldberg C, Hyde TM, Chen S, Dreses-Werringloer U, Herman MM, Kleinman JE, Davies P, Goldberg TE. Molecular signatures in post-mortem brain tissue of younger individuals at high risk for Alzheimer’s disease as based on APOE genotype. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:836–847. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarajiwa SA, Forster S, Auchettl K, Hertzog PJ. INTERFEROME: the database of interferon regulated genes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009 Jan;37(Database Issue):D852–D857. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh HS, Cosenza-Nashat M, Choi N, Zhao ML, Li JF, Pollard JW, Jirtle RL, Goldstein H, Lee SC. Insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor is an IFNgamma-inducible microglial protein that facilitates intracellular HIV replication: implications for HIV-induced neurocognitive disorders. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2446–2458. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JE, Kerr IM, Stark GR. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science. 1994;264:1415–1421. doi: 10.1126/science.8197455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakansson P, Segal D, Lassen C, Gullberg U, Morse HC, Fioretos T, Meltzer PS. Identification of genes differentially regulated by the P210 BCR/ABL1 fusion oncogene using cDNA microarrays. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Commane M, Flickinger TW, Horvath CM, Stark GR. Defective TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis in STAT1-null cells due to low constitutive levels of caspases. Science. 1997;278:1630–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephanou A, Brar BK, Scarabelli TM, Jonassen AK, Yellon DM, Marber MS, Knight RA, Latchman DS. Ischemia-induced STAT-1 expression and activation play a critical role in cardiomyocyte apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10002–10008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephanou A, Scarabelli TM, Brar BK, Nakanishi Y, Matsumura M, Knight RA, Latchman DS. Induction of apoptosis and Fas receptor/Fas ligand expression by ischemia/reperfusion in cardiac myocytes requires serine 727 of the STAT-1 transcription factor but not tyrosine 701. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:28340–28347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101177200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangano EN, Litteljohn D, So R, Nelson E, Peters S, Bethune C, Bobyn J, Hayley S. Interferon-gamma plays a role in paraquat-induced neurodegeneration involving oxidative and proinflammatory pathways. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;33:1411–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West DA, Valentim LM, Lythgoe MF, Stephanou A, Proctor E, van der Weerd L, Ordidge RJ, Latchman DS, Gadian DG. MR image-guided investigation of regional signal transducers and activators of transcription-1 activation in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2004;127:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedoni S, Olianas MC, Onali P. Interferon-beta induces apoptosis in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells through activation of JAK-STAT signaling and down-regulation of PI3K/Akt pathway. J Neurochem. 2010;115:1421–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander M, Forster C, Sugimoto K, Clark HB, Vogel S, Ross ME, Iadecola C. Interferon regulatory factor-1 immunoreactivity in neurons and inflammatory cells following ischemic stroke in rodents and humans. Acta Neuropathol. 2003;105:420–424. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0658-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens SL, Leung PY, Vartanian KB, Gopalan B, Yang T, Simon RP, Stenzel-Poore MP. Multiple preconditioning paradigms converge on interferon regulatory factor-dependent signaling to promote tolerance to ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2011;31:8456–8463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0821-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrangelo MA, Sudol KL, Narrow WC, Bowers WJ. Interferon-{gamma} differentially affects Alzheimer’s disease pathologies and induces neurogenesis in triple transgenic-AD mice. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:2076–2088. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1.Neurogenesis is apparently lost in AblPP/tTA mice with age. Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling of the dentate gyrus of wild-type versus AblPP/tTA mice at 11 weeks off doxycyline. Scalebars = 400 μm. The localization of BrdU labeled cells is consistent with the distribution of neuroblasts.