Abstract

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 is increased in different models of acute lung injury, and is an important determinant of survival and proliferation in many cells. We previously demonstrated that treatment of mice with IGF-1 receptor–blocking antibody (A12) improved early survival in bleomycin-induced lung injury. We have now examined whether administration of A12 improved markers of lung injury in hyperoxia model of lung injury. C57BL/6 mice underwent intraperitoneal administration of A12 or control antibody (keyhole limpet hemocyanin [KLH]), then were exposed to 95% hyperoxia for 88–90 hours. Mice were killed and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and lung tissue were obtained for analysis. Hyperoxia caused a significant increase in IGF levels in BAL and lung lysates. Peripheral blood neutrophils expressed IGF-1R at baseline and after hyperoxia. BAL neutrophils from hyperoxia-treated mice and patients with acute lung injury also expressed cell surface IGF-1R. A12-treated mice had significantly decreased polymorphonuclear cell (PMN) count in BAL compared with KLH control mice (P = 0.02). BAL from A12-treated mice demonstrated decreased PMN chemotactic activity compared with BAL from KLH-treated mice. Pretreatment of PMNs with A12 decreased their chemotactic response to BAL from hyperoxia-exposed mice. Furthermore, IGF-1 induced a dose-dependent chemotaxis of PMNs. There were no differences in other chemotactic cytokines in BAL, including CXCL1 and CXCL2. In summary, IGF blockade decreased PMN recruitment to the alveolar space in a mouse model of hyperoxia. Furthermore, the decrease in BAL PMNs was at least partially due to a direct effect of A12 on PMN chemotaxis.

Keywords: insulin-like growth factor, hyperoxia-induced lung injury, neutrophils

Clinical Relevance

In this study, we demonstrate, for the first time, that administration of a function-blocking antibody to insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 receptor leads to decreased neutrophilic inflammation in a murine model of hyperoxia-induced lung injury. We show that this is due to decreased bronchoalveolar lavage chemotactic activity. Furthermore, we demonstrate that IGF-1 is a direct chemotactic factor for neutrophils.

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 is an important prosurvival factor for many different cell types (1, 2). The IGF pathway can be protective of injury (3) or worsen injury (4, 5), depending on the organ system and the insult. The biological effects of IGF-1 are mediated through interactions with the cell surface receptor, IGF-1 receptor 1R (IGF-1R). We previously demonstrated that mice treated with blocking antibody to IGF-1R, the primary receptor for IGF-1, had improved early survival after bleomycin, as well as improved late resolution of fibrosis (4). The intratracheal administration of bleomycin to mice produces acute lung injury by a mechanism that involves free radical formation and oxidant stress. Although mechanistically different, hyperoxia also induces acute lung injury in mice through generation of reactive oxygen species. Mice heterozygous for IGF-1R have increased resistance to oxidative stress (6, 7). Both IGF and its receptor, IGF-1R, are up-regulated in the lung during hyperoxia and subsequent recovery phase (8). Several studies have demonstrated a role of IGF in the proliferative response of epithelial cells and fibroblasts during hyperoxia-induced lung injury (8, 9). In this study. we asked whether we would see differences in lung injury in a mechanistically different model of lung injury (hyperoxia) by blockade of IGF-1R.

Materials and Methods

Antibody

A12 is a fully human antibody antagonist to human IGF-1R, previously generated by screening a naive bacteriophage Fab library (10, 11). A12 and isotype control antibody (IgG1) to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) were a generous gift from Dale Ludwig (ImClone Systems). A12 inhibits IGF-1R signaling in murine and human tissues, and does not cross-react with the insulin receptor (10). We verified that our preparation of A12 was endotoxin free by Limulus Amebocyte Lysate assay (Cambrex BioScience, Baltimore, MD).

Hyperoxia Model

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Washington (Seattle, WA). All experimental procedures were performed in 8- to 10-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were placed in a sealed, plexiglass chamber, through which 100% oxygen was continuously flowing at 4.5–5 L/min. Oxygen fraction was checked three times per day and maintained at more than 95% at all times. A12 (40 mg/kg), or anti-KLH control antibody was injected intraperitoneally at 1 hour before placing them in the hyperoxia chamber. After 88–90 hours of hyperoxia exposure, whole-lung lavage was performed with 1 ml of PBS containing 0.6 mM EDTA. Total cell count in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was determined by Easycount Viasure Kit (Immunicon, Huntigdon, PA) and cell differential was determined on Diff-Quik (Dade Behring AG, Düdingen, Switzerland)–stained cytospins. After brief centrifugation, cell-free supernatants were used for measurement of total protein by Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). After lavage, the left main stem bronchus was tied off and the left lung was divided, and half was placed in RNAlater (Quiagen, Valencia, CA) and the other half was snap frozen and stored at −80°C for later processing. The right lung was inflated at a pressure of 25 cm H2O and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for histologic evaluation. For each set of experiments, four to five mice per group were used each time, and repeated three times.

BAL Neutrophil Chemotaxis Activity

Neutrophils were isolated from mouse bone marrow, as described previously (12, 13). After isolation, neutrophils were labeled with calcein AM (5 μg/ml; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 minutes, washed twice in PBS, and resuspended at a concentration of 2 × 106/ml. BAL fluid from KLH-treated or A12-treated mice was added to wells of 96-well plates, followed by placement of polycarbonate filters with 8-μm pores onto the plate. To determine whether IGF alone induced neutrophil chemotaxis, recombinant IGF alone was added to the wells. CXCL1 (KC) 50 ng/ml (PerroTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) was used as a positive control. Calcein-labeled neutrophils were added to the top of the filter. In some cases, neutrophils were preincubated with A12 antibody (400 μg/ml) for 1 hour before chemotaxis assay. The chemotaxis chamber was incubated for 30 minutes (37°C and 5% CO2). Nonmigrated neutrophils were removed from the upper side of the filter and the number of migrated cells was measured using Synergy 4 fluorescence plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). Each sample was run in at least triplicate, and experiments were repeated at least three times.

Results

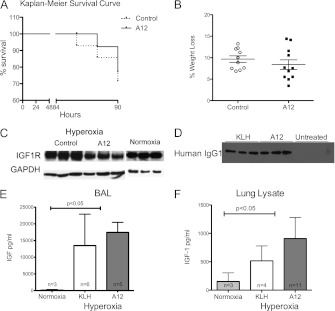

No Difference in Survival or Weight Loss between KLH- and A12-Treated Control after Hyperoxia

In control mice, 10 of 14 mice (71%) survived, and in A12-treated mice, 11 of 14 mice (79%) survived (Figure 1A). Differences were not statistically significant. After hyperoxia exposure for 88–90 hours, both groups showed significant weight loss: during the experimental period, the A12-treated mice lost an average of 8.38% of body weight, and the mice from the control group lost an average of 9.67% of body weight (Figure 1B). To demonstrate efficacy of systemic A12 treatment in the lung, we examined IGF-1R expression in the lungs of A12 mice and KLH-treated mice after hyperoxia. We found marked decreases in IGF-1R expression in lung lysates from A12-treated mice compared with KLH-treated mice or normoxic mice (Figure 1C), consistent with A12’s known mechanism of inducing a rapid internalization and degradation of IGF-1R (10), in addition to preventing binding of IGF to IGF-1R. In addition, we were able to detect human IgG1 in BAL from A12- or KLH-treated mice, but not from untreated mice (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

(A) Kaplan-Meier survival curve over time. A12 (n = 11) versus control (n = 10) (P = 0.69). (B) Percent weight loss after 90 hours of hyperoxia. A12 versus control (P = 0.69). (C) Decreased insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 receptor (IGF-1R) expression after systemic A12 administration. Western blot analysis for IGF-1R from whole-lung lysates after 90 hours of hyperoxia treated with KLH (control IgG), A12, or at baseline (normoxia). Bottom: loading control with GAPDH. (D) Antibody detection in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) after 90 hours of hyperoxia treated with KLH, A12, or untreated (normoxia). (E and F) IGF-1 levels in BAL (E) and lung lysates (F) at baseline (normoxia) or after 90 hours of hyperoxia. P < 0.05 between hyperoxia and normoxia; no significant difference between A12 or KLH by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD.

Hyperoxia Increased IGF Levels

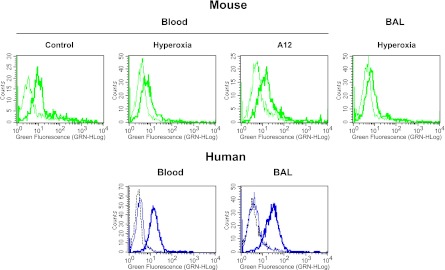

At baseline, we detected very low levels of IGF-1 in BAL or lung lysate. However, after 90 hours of hyperoxia, there was a significant increase in IGF-1 levels in BAL, and, to a lesser extent, in lung lysates (Figures 1E and 1F). There were no significant differences in IGF-1 levels between A12-treated and KLH-treated mice in either BAL or lung lysate. We confirmed that mouse peripheral blood neutrophils expressed cell surface IGF-1R at baseline (Figure 2, top). There was not a significant difference in IGF-1R expression by circulating neutrophils from mice treated with hyperoxia or A12 compared with normoxia. Neutrophils isolated from BAL after hyperoxia also expressed IGF-1R (Figure 2). We also asked whether human neutrophils expressed IGF-1R. We found that both human peripheral neutrophils and neutrophils isolated from BAL of patients with acute lung injury expressed IGF-1R by flow cytometry (Figure 2, bottom). No significant differences in IGF-1R expression were noted between blood and BAL neutrophils.

Figure 2.

IGF-1R expression in mouse and human neutrophils by flow cytometry. Top: mouse peripheral blood neutrophils isolated from normoxic, hyperoxic, or A12-treated mice (left), or mouse BAL neutrophils from hyperoxia-treated mice (right). Bottom: human peripheral blood neutrophils or BAL neutrophils from patients with acute lung injury. Thin line: FITC-labeled isotype control antibody; thick line: FITC-labeled anti–IGF-1R antibody; dotted black line: unstained negative control. Representative histograms of n = 2–3 independent samples per experimental group.

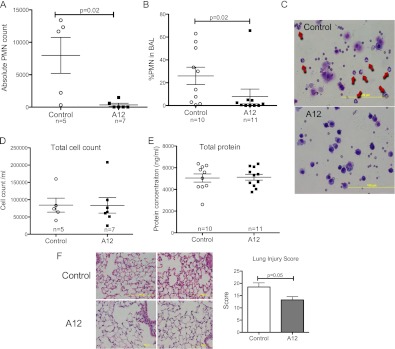

IGF-1 Blockade Attenuated Inflammation in the Lung

There was a significant decrease in both the absolute polymorphonuclear cell (PMN) count (Figure 3A) and percentage of PMNs (Figure 3B) in BAL from A12-treated mice compared with control (Figure 3C), whereas total BAL cell count was similar in both groups (Figure 3D). There were no differences in peripheral PMN counts between control and A12-treated mice (26 ± 6% versus 35 ± 14%; P = 0.3). There was no difference in BAL total protein or RBC count between the two groups (Figure 3E, and data not shown). Histological evaluation of lung sections showed less intra-alveolar exudate, fewer inflammatory cells, and decreased alveolar wall thickening in lungs from A12-treated mice compared with control mice (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

(A and B) IGF-1 blockade with A12 decreased BAL polymorphonuclear cell (PMN) count after 90 hours of hyperoxia. (C) Representative BAL cytospins demonstrate decreased PMNs (arrows) with A12 treatment. (D) BAL total cell count. (E) BAL total protein. Each point represents an individual mouse. (F) Histology of A12-treated mice and control mice after 90 hours of hyperoxia. Lung sections from A12-treated mice show relatively normal interstitium and less infiltrate compared with control mice. Right middle lobe from two mice/group shown. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Graph: lung injury score (n = 6/group). Mean values (±SD) are shown.

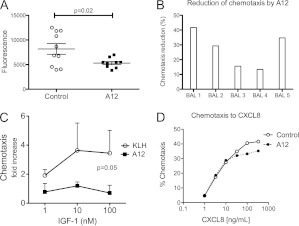

Decreased Chemotactic Activity in BAL

We next asked whether there were differences in BAL chemotactic activity that would account for decreased neutrophil accumulation in A12-treated mice. We used a rapid fluorescence-based assay to compare the ability of BAL from A12-treated or control mice to induce neutrophil migration. We found significantly less neutrophil chemotaxis toward BAL from A12-treated mice compared with KLH-treated mice (Figure 4A). In addition, pretreatment of neutrophils with A12 decreased chemotaxis toward BAL from KLH-treated mice by an average of 27 (±12)% (P = 0.01; Figure 4B). Furthermore, we found that IGF induced a modest but significant increase in neutrophil chemotaxis compared with BSA, which was completely inhibited by A12 (Figure 4C). A12 treatment did not inhibit PMN chemotaxis toward CXCL1 at lower chemokine concentrations, but, interestingly, had a small but significant inhibitory effect at higher (≥100 ng/ml) CXCL1 doses (100 ng/ml CXCL1 ± A12: 33 versus 24%). Similarly, chemotaxis of human neutrophils to CXCL8 was partially inhibited by A12 only at high concentrations of CXCL8 (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

(A) Decreased BAL chemotactic activity for PMNs after A12 treatment after 90 hours of hyperoxia (n = 10/group). (B) Decreased chemotaxis of A12-treated PMNs to BAL from hyperoxia-exposed mice. (C) IGF-1 induces chemotaxis of PMNs, which is inhibited by A12 (A12 versus IGF; P = 0.05; n = 3). (D) Dose response of CXCL8-induced PMN chemotaxis with and without A12 (400 μg/ml).

Cytokine Expression Profile in Lung and BAL

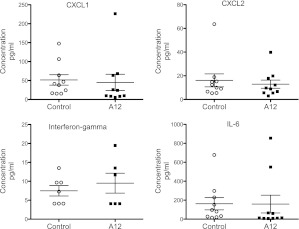

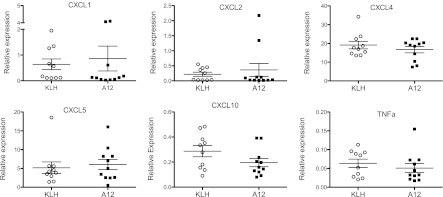

We examined differences in potential neutrophil chemotactic agents in BAL. There were no significant differences in CXCL1, CXCL2, IL-6, or IFN-γ between the two groups (Figure 5). Levels of IL-1, TNF-α, and granulocyte/macrophage colony–stimulating factor were below the detection limits in BAL from both groups. We examined the expression of CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL4, CXCL5, CXCL10, and TNF-α in lung homogenate by RT-PCR, but did not find any significant differences (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Chemokine levels in BAL after 90 hours of hyperoxia. Each point represents an individual mouse (n = 10/group). Mean values (±SEM) are shown.

Figure 6.

Real-time PCR analysis of select cytokines in mouse lungs after hyperoxia (90 h). Data were normalized to GAPDH expression. Each point represents an individual mouse (n = 10/group). Mean values (±SEM) are shown.

Discussion

Hyperoxia-induced lung injury is characterized by inflammatory cell recruitment, especially PMNs, and increased capillary and epithelial permeability (14). We found that hyperoxia significantly increased IGF-1 levels in BAL and lung lysates. The magnitude of change of total IGF-1 levels was similar to what we observed in BAL from patients with acute lung injury (15). To determine the contribution of IGF pathway to lung injury after hyperoxia, we used A12, a function-blocking antibody to the human IGF-1R (10, 11). After hyperoxia, neutrophil influx typically occurs by Day 3 (16, 17). Despite the mild degree of cellular infiltrate and abnormalities after hyperoxia, we found subtle differences in inflammation by histology in A12-treated mice. More significant was the decreased number of neutrophils in BAL in mice after systemic treatment with A12 in the setting of hyperoxia. We confirmed that BAL from hyperoxic mice induces neutrophil chemotaxis (18). In addition, we showed that BAL from A12-treated mice induced significantly less neutrophil chemotaxis compared with BAL from control mice after hyperoxia. We showed that IGF-1 directly induced neutrophil chemotaxis, which was inhibited by A12. Furthermore, pretreatment of neutrophils with A12 decreased chemotaxis in response to BAL from hyperoxic mice. We were only able to partially block neutrophil chemotaxis with A12 pretreatment, suggesting that other chemokines in BAL contribute to neutrophil chemotaxis. Indeed, we found elevated levels of several known neutrophil chemoattractants, including CXCL1 and CXCL2, in BAL from hyperoxic animals. However, we did not find differences in these or other chemokines in either BAL fluid or lung homogenates of A12 mice compared with control antibody–treated mice. We also demonstrated expression of IGF-1R on mouse and human neutrophils at baseline, and showed persistent expression of IGF-1R by both blood and BAL neutrophils after injury. This adds new information to a previous study that demonstrated expression of IGF-1R on bovine monocytes and neutrophils (19). Our data suggest that hyperoxia induces IGF-1 expression in lung and BAL fluid, which then acts as a chemoattractant for neutrophils that express IGF-1R. One potential mechanism for the observed decrease in chemotactic activity of BAL from A12-treated mice is direct blockade of neutrophil IGF-1R by the antibody that is present in BAL.

In addition to its known prosurvival and proproliferative role, IGF-1 induces migration of a variety of normal and malignant cell types, including lung fibroblasts (4, 20), colonic epithelial cells (21), human melanoma (22), pancreatic carcinoma (23), and arterial smooth muscle cells (24, 25). In nonadherent cells, IGF-1 increased migration of multiple myeloma cells across endothelial monolayer in a phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent pathway (26, 27). Our results suggest that the decreased BAL neutrophil count in A12-treated mice was due to a direct effect on neutrophils, rather than a secondary effect on secretion of other neutrophil chemotactic agents.

Despite differences in neutrophil recruitment, we did not see a difference in survival or other markers of injury, such as BAL protein level. Despite the influx of neutrophils after hyperoxia, their contribution to injury and outcome in hyperoxia is controversial. One early study demonstrated that neutropenic rabbits developed a similar degree of capillary leak after hyeproxia (28). Another study demonstrated that blockade of PMN recruitment by several different methods did not alter ultimate lung injury and survival during hyperoxia (29). Together with our data, these studies demonstrate dissociation between PMN recruitment and lung injury during hyperoxia in mice.

We previously demonstrated that IGF-1R blockade with A12 improved survival after bleomycin-induced lung injury, with deaths in the control group occurring at Days 5–7 after bleomycin. We did not see differences in BAL cell count or differential in our study. However, the first time point examined was Day 7. Therefore, we may have missed earlier differences in neutrophil recruitment. Because bleomycin causes a much more severe inflammatory reaction and neutrophil influx compared with hyperoxia lung injury, we suspect that any differences in neutrophil recruitment with IGF blockade may not be apparent in that model. Our results demonstrate that A12-treated neutrophils still underwent chemotaxis in response to CXCL1, indicating that neutrophils are capable of responding to other chemotactic agents. We did see a modest inhibition of CXCL1-induced chemotaxis at high concentrations of CXCL1. One possibility is that high concentrations of CXCL1 induce expression of IGF-1 by neutrophils, whose affect is inhibited by A12.

There are conflicting reports on the role of IGF-1 in different models of organ injury and sepsis. A number of studies demonstrated that exogenous administration of IGF-1 decreased tissue injury in different injury models, including renal ischemia–reperfusion (30), burns (31), and sepsis (32, 33). Because IGF-1 can have a prosurvival effect on epithelial cells, it is difficult to assess the direct contribution of IGF-1 to neutrophil recruitment and activation. Release of factors from apoptotic epithelial cells, such as endothelial monocyte-activating polypeptide (EMAP) II, can recruit neutrophils to sites of injury (30). For example, in a model of stress-induced gastric mucosal injury, IGF-1 administration decreased injury and decreased gastric myeloperoxidase levels (3). However, the study demonstrated a significant decrease in mucosal injury and apoptosis; the decreased myeloperoxidase activity may have been secondary to decreased recruitment due to less epithelial injury. In contrast, our data are consistent with the effect of exogenous IGF-1 administration during ischemia model of kidney injury (5). IGF-1–treated rats showed more histological evidence of injury and increased numbers of neutrophils compared with control animals (5). In addition, mice hypomorphic for IGF-1R demonstrated less histologic evidence of injury and improved survival when mice were exposed to hyperoxia for 72 hours, followed by normoxia for 48 hours (6). The mortality difference occurred during the normoxia re-exposure period.

In addition to an effect on migration, we cannot exclude additional contributions of the IGF pathway to differences in neutrophil cell count. Another potential contributing factor to differences in neutrophil count may be the role of IGF on neutrophil survival. Prior published work demonstrated that IGF can decrease neutrophil apoptosis (34). Therefore, it is possible that blockade of IGF through A12 administration induced neutrophil apoptosis, which also contributed to decreased BAL neutrophil counts.

Previous work has suggested that IGF contributes to fibroproliferation in hyperoxia lung injury (9). In this study, we demonstrate, for the first time, that administration of a function-blocking antibody to IGF-1R leads to decreased neutrophilic inflammation in a murine model of hyperoxia-induced lung injury. We show that this is due to decreased BAL chemotactic activity. Furthermore, we demonstrate that IGF-1 is a direct chemotactic factor for neutrophils. Thus, our study demonstrates an additional function of IGF pathway in neutrophil recruitment in lung injury. We speculate that the net effect of IGF blockade during injury models will be a balance of its role in prosurvival of epithelial cells/mucosa and its role in neutrophil recruitment.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by an American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid, by National Institutes of Health grants HL083481 and K24HL068796 (L.M.S.), and by a Parker B. Francis Fellowship (S.E.G.).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0085OC on April 5, 2012

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Kurmasheva RT, Houghton PJ. IGF-I mediated survival pathways in normal and malignant cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006;1766:1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LeRoith D, Roberts CT., Jr The insulin-like growth factor system and cancer. Cancer Lett 2003;195:127–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao J, Harada N, Sobue K, Katsuya H, Okajima K. Insulin-like growth factor-I reduces stress-induced gastric mucosal injury by inhibiting neutrophil activation in mice. Growth Horm IGF Res 2009;19:136–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi JE, Lee SS, Sunde DA, Huizar I, Haugk KL, Thannickal VJ, Vittal R, Plymate SR, Schnapp LM. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor blockade improves outcome in mouse model of lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:212–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandez M, Medina A, Santos F, Carbajo E, Rodriguez J, Alvarez J, Cobo A. Exacerbated inflammatory response induced by insulin-like growth factor I treatment in rats with ischemic acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001;12:1900–1907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahamed K, Epaud R, Holzenberger M, Bonora M, Flejou JF, Puard J, Clement A, Henrion-Caude A. Deficiency in type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor in mice protects against oxygen-induced lung injury. Respir Res 2005;6:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holzenberger M, Dupont J, Ducos B, Leneuve P, Geloen A, Even PC, Cervera P, Le Bouc Y. IGF-1 receptor regulates lifespan and resistance to oxidative stress in mice. Nature 2003;421:182–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narasaraju TA, Chen H, Weng T, Bhaskaran M, Jin N, Chen J, Chen Z, Chinoy MR, Liu L. Expression profile of IGF system during lung injury and recovery in rats exposed to hyperoxia: a possible role of IGF-1 in alveolar epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation. J Cell Biochem 2006;97:984–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chetty A, Nielsen HC. Regulation of cell proliferation by insulin-like growth factor 1 in hyperoxia-exposed neonatal rat lung. Mol Genet Metab 2002;75:265–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burtrum D, Zhu Z, Lu D, Anderson DM, Prewett M, Pereira DS, Bassi R, Abdullah R, Hooper AT, Koo H, et al. A fully human monoclonal antibody to the insulin-like growth factor I receptor blocks ligand-dependent signaling and inhibits human tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res 2003;63:8912–8921 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu JD, Odman A, Higgins LM, Haugk K, Vessella R, Ludwig DL, Plymate SR. In vivo effects of the human type I insulin-like growth factor receptor antibody A12 on androgen-dependent and androgen-independent xenograft human prostate tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11:3065–3074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boxio R, Bossenmeyer-Pourie C, Steinckwich N, Dournon C, Nusse O. Mouse bone marrow contains large numbers of functionally competent neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol 2004;75:604–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gill SE, Huizar I, Bench EM, Sussman SW, Wang Y, Khokha R, Parks WC. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 3 regulates resolution of inflammation following acute lung injury. Am J Pathol 2010;176:64–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matute-Bello G, Frevert CW, Martin TR. Animal models of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;295:L379–L399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnapp LM, Donohoe S, Chen J, Sunde DA, Kelly PM, Ruzinski J, Martin T, Goodlett DR. Mining the acute respiratory distress syndrome proteome: identification of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF)/IGF-binding protein-3 pathway in acute lung injury. Am J Pathol 2006;169:86–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers LK, Tipple TE, Nelin LD, Welty SE. Differential responses in the lungs of newborn mouse pups exposed to 85% or >95% oxygen. Pediatr Res 2009;65:33–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Zoelen MAD, Florquin S, de Beer R, Pater JM, Verstege MI, Meijers JCM, van der Poll T. Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor–deficient mice demonstrate reduced hyperoxia-induced lung injury. Am J Pathol 2009;174:2182–2189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox RB, Hoidal JR, Brown DM, Repine JE. Pulmonary inflammation due to oxygen toxicity: involvement of chemotactic factors and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Am Rev Respir Dis 1981;123:521–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen L, Rontved CM, Nielsen MO, Norup LR, Ingvartsen KL. Leukocytes from heifers at different ages express insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptors. Domest Anim Endocrinol 2003;25:231–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chetty A, Faber S, Nielsen HC. Epithelial–mesenchymal interaction and insulin-like growth factors in hyperoxic lung injury. Exp Lung Res 1999;25:701–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andre F, Rigot V, Thimonier J, Montixi C, Parat F, Pommier G, Marvaldi J, Luis J. Integrins and E-cadherin cooperate with IGF-I to induce migration of epithelial colonic cells. Int J Cancer 1999;83:497–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stracke ML, Engel JD, Wilson LW, Rechler MM, Liotta LA, Schiffmann E. The type I insulin-like growth factor receptor is a motility receptor in human melanoma cells. J Biol Chem 1989;264:21544–21549 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooks PC, Klemke RL, Schon S, Lewis JM, Schwartz MA, Cheresh DA. Insulin-like growth factor receptor cooperates with integrin alpha v beta 5 to promote tumor cell dissemination in vivo. J Clin Invest 1997;99:1390–1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bornfeldt KE, Raines EW, Nakano T, Graves LM, Krebs EG, Ross R. Insulin-like growth factor-I and platelet-derived growth factor-BB induce directed migration of human arterial smooth muscle cells via signaling pathways that are distinct from those of proliferation. J Clin Invest 1994;93:1266–1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duan C, Bauchat JR, Hsieh T. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is required for insulin-like growth factor-I–induced vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration. Circ Res 2000;86:15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiang YW, Yao L, Tosato G, Rudikoff S. Insulin-like growth factor I induces migration and invasion of human multiple myeloma cells. Blood 2004;103:301–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tai YT, Podar K, Catley L, Tseng YH, Akiyama M, Shringarpure R, Burger R, Hideshima T, Chauhan D, Mitsiades N, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 induces adhesion and migration in human multiple myeloma cells via activation of beta1-integrin and phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/AKT signaling. Cancer Res 2003;63:5850–5858 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raj JU, Hazinski TA, Bland RD. Oxygen-induced lung microvascular injury in neutropenic rabbits and lambs. J Appl Physiol 1985;58:921–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perkowski S, Scherpereel A, Murciano J-C, Arguiri E, Solomides CC, Albelda SM, Muzykantov V, Christofidou-Solomidou M. Dissociation between alveolar transmigration of neutrophils and lung injury in hyperoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;291:L1050–L1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daemen MA, van 't Veer C, Denecker G, Heemskerk VH, Wolfs TG, Clauss M, Vandenabeele P, Buurman WA. Inhibition of apoptosis induced by ischemia–reperfusion prevents inflammation. J Clin Invest 1999;104:541–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeschke MG, Bolder U, Chung DH, Przkora R, Mueller U, Thompson JC, Wolf SE, Herndon DN. Gut mucosal homeostasis and cellular mediators after severe thermal trauma and the effect of insulin-like growth factor-I in combination with insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3. Endocrinology 2007;148:354–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen K, Okuma T, Okamura K, Tabira Y, Kaneko H, Miyauchi Y. Insulin-like growth factor-I prevents gut atrophy and maintains intestinal integrity in septic rats. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1995;19:119–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukushima R, Saito H, Inoue T, Fukatsu K, Inaba T, Han I, Furukawa S, Lin MT, Muto T. Prophylactic treatment with growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor I improve systemic bacterial clearance and survival in a murine model of burn-induced gut-derived sepsis. Burns 1999;25:425–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kooijman R, Coppens A, Hooghe-Peters E. IGF-I inhibits spontaneous apoptosis in human granulocytes. Endocrinology 2002;143:1206–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.