Abstract

Objectives

To describe experiences with the implementation of global trigger tool (GTT) reviews in five Danish hospitals and to suggest ways to improve the performance of GTT review teams.

Design

Retrospective observational study.

Setting

The measurement and monitoring of harms are crucial to campaigns to improve the safety of patients. Increasingly, teams use the GTT to review patient records and measure harms in English and non-English-speaking countries. Meanwhile, it is not clear as to how the method performs in such diverse settings.

Participants

Review teams from five Danish pilot hospitals of the national Danish Safer Hospital Programme.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

We collected harm rates, background and anecdotal information and reported patient safety incidents (PSIs) from five pilot hospitals currently participating in the Danish Safer Hospital Programme. Experienced reviewers categorised harms by type. We plotted harm rates as run-charts and applied rules for the detection of patterns of non-random variation.

Results

The hospitals differed in size but had similar patient populations and activity. PSIs varied between 3 and 12 per 1000 patient-days. The average harm rate for all hospitals was 60 per 1000 patient-days ranging from 34 to 84. The percentage of harmed patients was 25 and ranged from 18 to 33. Overall, 96% of harms were temporary. Infections, pressure ulcers procedure-related and gastrointestinal problems were common. Teams reported differences in training and review procedures such as the role of the secondary reviewer.

Conclusions

We found substantial variation in harm rates. Differences in training, review procedures and documentation in patient records probably contributed to these variations. Training reviewers as teams, specifying the roles of the different reviewers, training records and a database for findings of reviews may improve the application of the GTT.

Keywords: Audit

Article summary.

Article focus

To describe experiences with the implementation of global trigger tool (GTT) reviews in five Danish hospitals.

To suggest ways to improve the performance of GTT review teams.

Key messages

Differences in training, review processes and documentation can contribute to differences GTT results.

Systematic training of review teams, standardisation of review processes and feedback on results should improve the performance of review teams.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study supplies detailed contextual information that is relevant for the implementation of the GTT that increasingly is being used to monitor the safety in hospitals.

The observational study design dose not allow for conclusions on causality and quantification of the contributions of different factors with relevance for the implementation of GTT reviews.

Background

Patients run a high risk of being harmed during hospital admissions. Adverse events occur in up to 10% of hospitalisations and can cause death, permanent or temporary disability.1 For patients and healthcare workers, these harms and the underlying flaws of their healthcare systems that permit them to happen are deeply upsetting and completely unacceptable.

To improve the safety of patients, national and regional campaigns have been carried through2–5 or are ongoing.6 Improvements have been achieved in some areas such as reductions of catheter-related blood stream infections.7 However, system-wide progress is slow8 and improvements are often limited to particular medical conditions or institutions. Indeed, a recent study9 from the state of North Carolina, an active participant in large-scale patient safety initiatives, concluded that overall rates of harm during 2002–2007 were not reduced. Thus, the challenge to improve the safety of patients in hospitals remains and specific and sensitive measures of harms are needed to assess and monitor the effects of changes to make hospitals safer.

In Denmark, the Operation Life campaign during 2006–2008 focused on patient safety in intensive care and during surgery. An estimated 1654 fewer than expected patients died in the Danish population of 5.5 million during the campaign.10 In 2010, another campaign the Safer Hospital Programme (http://www.sikkerpatient.dk/fagfolk/patientsikkert-sygehus.aspx) was launched at five pilot hospitals to reduce mortality by 15% and harms by 30% through the implementation of 12 care bundles. The hospitals are required to measure and report harms.

Meanwhile, a gold standard for the measurement of harms does not exist. Methods like voluntary reports only detect a small fraction of harms,11 chart reviews have low inter-rater reliability12 and are very time consuming and so are direct observations of healthcare processes.13 Studies comparing different methods of harm detection have found very little overlap of the detected harms.14 Therefore, complete estimates of the incidence of harms probably require the combination of different methods. Meanwhile, such an approach is time consuming and results are often delayed, which is unsuitable for patient safety campaigns in which frequent and regular measurements of harms are needed to evaluate and monitor the effects of interventions and organisational changes.

The global trigger tool (GTT) has been developed for the purpose of monitoring harms at low cost.15 Harm in this context is defined as an ‘Unintended physical injury resulting from or contributed to by medical care that requires additional monitoring, treatment or hospitalisation, or that results in death’.16 Thus, the tool measures factual harm to patients, while errors not leading to harm, near errors and errors of omission are not included. A GTT review is a trigger-based chart audit of closed patient charts. Two reviewers, usually nurses or pharmacists, each review a limited number of randomly chosen charts with a given set of 56 triggers or “hints” of errors. The finding of such a hint triggers an investigation into whether and, if so, how severely, a patient actually has been harmed. Review time is limited to 20 min per admission. Finally, the two reviewers compare their conclusions and a supervisor, usually a physician, qualifies the number and severity of harms and decides in cases of disagreement. The number of harms is then expressed as a rate, for example, harms per 1000 bed-days. It has been suggested that GTT teams need a limited amount of training and practice to achieve good levels of reliability to identify harms.16–18 The feasibility of the method invites for rapid adoption in healthcare systems around the world where practical ways to measure harms are much in demand. Nevertheless, experiences with the GTT in non-English-speaking countries are limited. Thus, careful calibration of the instrument and the review team that uses it is warranted to avoid evaluating the safety performance of hospitals with imprecise measurements.

A team of Danish experts translated the GTT to Danish19 from the English and a Swedish version.20 The tool was tested in four hospitals in different health regions.21 The harm rate in these hospitals was around 20 per 1000 bed-days. A recent report of harms to Danish patients with cancer found a rate of 68 per 1000 bed-days.22 Notwithstanding these variable rates, policy makers advocate the widespread23 implementation of GTT reviews in Danish hospitals. Meanwhile in our opinion, it is not sufficiently clear as to how the tool performs in the hands of Danish review teams.

The aim of this study was to describe experiences with the GTT in five Danish hospitals and suggest ways to improve the performance of GTT review teams and thus contribute to the accurate measurements of harms.

Methods

In this retrospective observational study, we present harm rates as measured by the GTT at the five hospitals participating in the Safer Hospital Programme in Denmark. The hospitals had used the GTT for 18 months from January 2010 until June 2011. The project managers at the hospitals supplied tabulated data on the size, activity and patient populations of the five hospitals from the year 2010. All data were collected between August and December 2011.

CvP, the project manager at one of the five hospitals and a consultant in pulmonary medicine, and AMK, a registered nurse and experienced GTT reviewer, interviewed members of the GTT teams and project managers on the telephone. The interviews comprised questions on the training of the GTT teams, team composition, roles of the team members and review processes. Moreover, they asked open questions about unexpected observations and changes. The GTT teams supplied lists of the recorded harms from their reviews.

To give an impression of the safety culture at the participating hospitals, we present the number and severity of reported patient safety incidents (PSIs) in 2010. JA, a physician by training who works in the Danish Society for Patient Safety, gathered these data from the Danish Patient Safety Database (www.dpsd.dk) for voluntary reporting of PSIs. Risk managers at the five hospitals classified the severity of PSIs in the Danish Safety Database into mild, moderate, severe and fatal. In Denmark, reporting of PSIs is mandatory, confidential and sanction free for healthcare personnel.

GTT review

The Danish translation of the GTT toolkit was the reference for the review teams.19 Teams were to review a random sample of 10 admissions twice a month. Closed admissions of patients of at least 18 years of age and of at least 24 h duration were eligible. The date of discharge was the index date. The GTT teams should review all available information from the admissions, that is, physician and nurse notes, medication orders and history as well as results of diagnostic tests. Each primary reviewer should review each record. Afterwards, the primary reviewers should meet to discuss harms and come to consensus. Finally, the primary reviewers should meet with the supervising physician to present their findings for approval and severity classification. Triggers, harms and the severity of harms should be recorded on standardised work sheets, then transferred to spreadsheets and stored locally. The team should classify the severity of harms according to the National Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention Index. The five hospitals only register harm rates in a shared database other data from GTT reviews are stored locally.

Data analysis

We calculated the monthly harms per 1000 bed days, harms per 100 admissions and the percentage of harmed patients. The harm rate was then plotted on a run chart and analysed using four run chart rules for the detection of patterns of non-random variation such as shifts or trends.24 We collected and managed the data in Microsoft Excel V.2003 and produced the statistical analysis and graphs in R Statistical Software V.2.13.1.

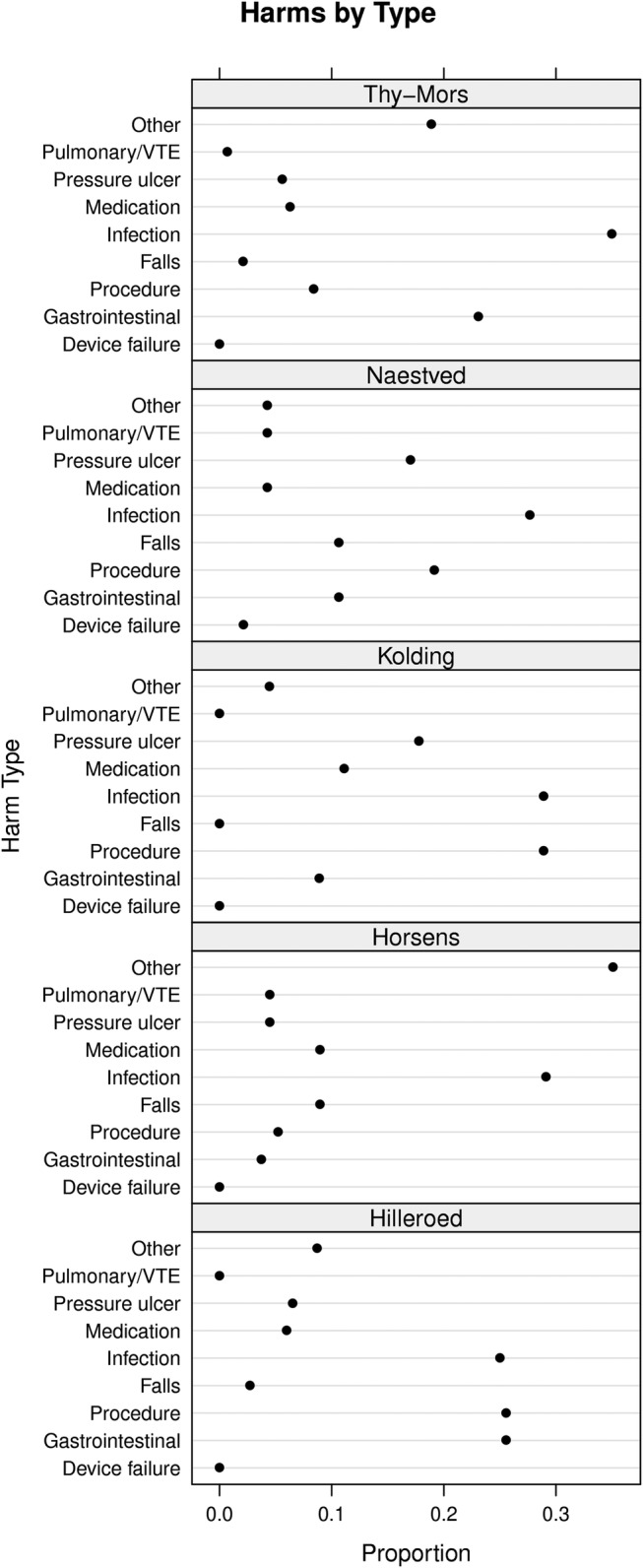

For the purpose of this study, two nurses from the GTT team of one of the hospitals who had done over 400 GTT reviews each retrospectively categorised harms found at all five hospitals into categories also used by Classen et al.25 They added gastrointestinal complications and pressure ulcers as categories because these were common types of harm (figure 1). Each harm was assigned to only one category.

Figure 1.

Harms by type. The dot plots show the relative distribution of harms by type. VTE, venous thromboembolism.

The regional ethical committee deemed an ethical review of the study unnecessary.

Results

Background data of the five pilot hospitals

The five hospitals, one in each Danish health region, vary in size but all hospitals have departments of internal medicine, orthopaedic and general surgery as well as obstetrics and gynaecology. All hospitals use electronic patient records, but to varying degree parts of the documentation, such as nursing notes, are on paper. The populations of patients at the five hospitals were similar with regard to age and gender distribution. There was a fourfold difference in reporting of PSIs among hospitals (table 1). Meanwhile, the distributions of PSIs by consequence were almost identical (figure 2).

Table 1.

Background information on the five hospitals (2010)

| Hilleroed | Horsens | Kolding | Naestved | Thy-Mors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharges | 60 098 | 30 377 | 27 526 | 28 677 | 11 836 |

| Average patient age (years) | 55 | 57 | 53 | 59 | 58 |

| Percent of females | 62 | 59 | 61 | 55 | 55 |

| Patient-days | 231 978 | 108 060 | 90 710 | 113 353 | 49 711 |

| Outpatient visits | 262 547 | 212 899 | 124 184 | 184 374 | 65 165 |

| Employees | 3163 | 1367 | 1507 | 1668 | 689 |

| Hospital standardised mortality rate | 95 | 97 | 96 | 112 | 100 |

| Reported safety incidents | 2736 | 365 | 923 | 1182 | 223 |

| Reported patient safety incidents per 1000 patient-days | 12 | 3 | 10 | 10 | 4 |

Figure 2.

Patient safety incidents by consequence. The dot plots show the relative distribution of patient safety incidents by consequence as reported to the Danish national database. Categories minor and moderate represent no and temporary harms, major permanent harms. Overall, 96% of the incidents were temporary.

Experiences with the implementation of the GTT

Reviewing patient files with the GTT was new to three of the five teams. Prior to the Safer Hospital Programme, Naestved and Hilleroed Hospital had been using the GTT for reviewing patient records for 1 and 2 years, respectively.

In May 2010, the GTT team from each of the five hospitals participated in a 7 h training session with experts in the method from Denmark and the Institute of Health Care Improvement (IHI). The session included an introduction to the Danish GTT manual, frontal teaching, review of three training records per team and plenary discussions of the findings (table 2). Only the review team at Hilleroed had in 2008 received a similar training. All teams used nurses as primary reviewers and physicians as supervisors. All teams received on-site expert coaching with reviews of 10 or more records, up to three times. The expert coach was a physician who was trained by experts from the IHI. Furthermore, all teams participated in two full-day network seminars during the study period. All teams started reviewing patient records for the measurement of their baseline in May 2010 and retrospectively reviewed records from January to May 2010.

Table 2.

Characteristics and review procedures of global trigger tool teams at five hospitals

| Hilleroed | Horsens | Kolding | Naestved | Thy-Mors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Team characteristics | |||||

| Number of physicians | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Number of nurses | 3 | 3 | 4 later 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Number of changes in team | 0 | 1 (physician) | 1 | 0 | 2 (nurses) |

| Review intervals | Twice per month | Monthly | Monthly (two half days) | Monthly | Variable |

| Training | |||||

| Hours of training | 14* | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Site visits by Danish expert (days) | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Complete team present during site visit | − | − | + | − | −f |

| Number of records reviewed together with expert | <10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| Review procedures | |||||

| Whole team meets for reviews | + | + | Since Jan. 2011 | − | − |

| Physician acts as judge (J) in cases of disagreement or reviewer (R) based on triggers | J | R | J | J | J |

| Records entirely electronic | − | + | + | − | + |

| Dedicated person responsible to find records | + | − | + | + | − |

| Secretary plots triggers and harms | − | − | − | − | + |

*Team also trained by national expert in 2008.

The compositions of teams changed between zero (Hilleroed and Naestved) and three times (Thy-Mors) during the study period. Review intervals at the hospitals varied between 2 weeks, 1 month and irregular. Complete teams reviewed together and compared findings at two, later three hospitals. The role of the physician in the review team varied from only judging cases where the primary reviewers were in doubt or disagreed (Hilleroed) to identifying harms based on triggers found by primary reviewers (Horsens). Table 2 shows differences in review procedures at the hospitals.

Anecdotal information about GTT reviews

At Naestved, the team sampled 24 records (in case some were incomplete) each month and sorted them in the order of the date of the admission and reviewed the first 20 records. Thus, the sample became biased towards admissions in the earlier part of the month. Moreover, the team initially reviewed only admissions to the last department of a hospital admission. Thus, they did not find harms that, for example, occurred during an admission to the intensive care unit earlier during the hospital stay. These errors were accidentally discovered during a site visit and the team did a new review for the period. The team at Kolding discovered after 3 months that their sampling procedure excluded admissions that had an appointment for ambulatory follow-up after surgery, and they decided to discard the first 3 months from their baseline.

GTT findings

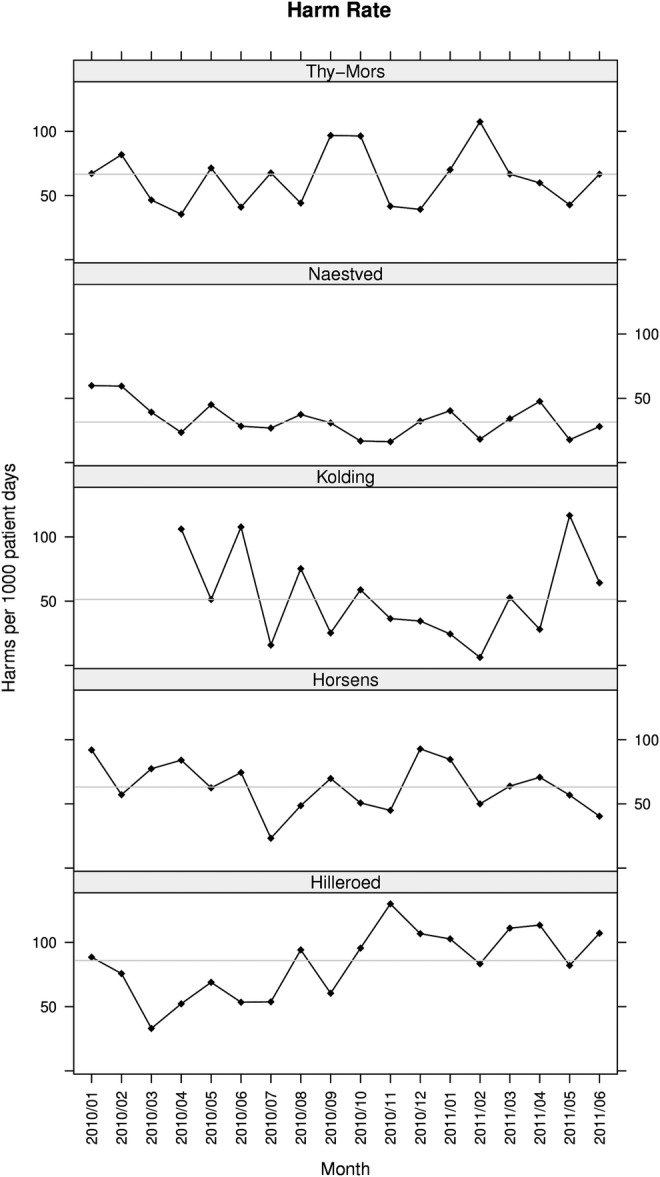

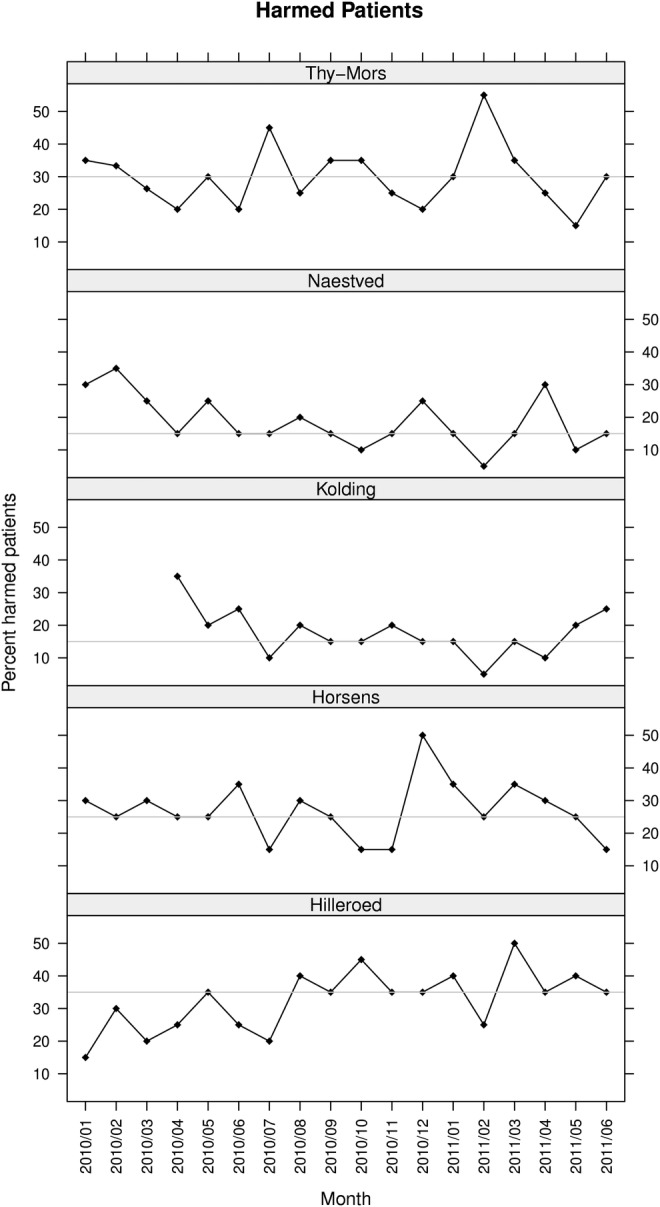

In total, 687 adverse events were identified in 11 487 patient-days, that is, the overall average harm rate was 60 per 1000 patient-days. The monthly harm rate ranged from 34 to 84 harms per 1000 patient-days (figure 3). The harm rates at all five hospitals showed only random variation.23 The overall numbers of harms per 100 admissions were at Thy Mors 45, Naestved 24, Kolding 30, Horsens 43 and Hilleroed 54. The percentage of harmed patients was 25, ranging from 18 (Horsens) to 33 (Hilleroed) (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Rates of harm. The run charts show monthly rates of harms measured with the global trigger tool. The curve shows the harm rate expressed as the number of adverse events per 1000 patient-days. The horizontal line is the median harm rate.

Figure 4.

Harmed patients. The run charts show the percentages of harmed patients measured with the global trigger tool. The horizontal line is the median percentage of harms.

Overall, 96% of harms were temporary (grades E and F). However, the severity distribution varied between hospitals (figure 5). Notably, the hospital with the highest harm rate (Hilleroed) also had the highest proportion of grade E harms.

Figure 5.

Harms by severity. The dot plots show the relative distribution of severity of harms in categories E—I, where E and F are temporary, G—H permanent harms and I death. Overall, 96% of harms were temporary.

Five hundred and fifty-three harms (80%) were recorded with sufficient detail in the hospital datasheets to categorise them by type. The proportion of harms without description varied: 5% (Kolding and Hilleroed), 12% (Thy-Mors and Horsens) and 45% (Naestved). Common types of harm were infections, procedure-related, pressure ulcers and gastrointestinal problems (figure 1).

Discussion

We observed marked differences in the harm rates and types identified by GTT review teams in five Danish public hospitals. The GTT is not designed to compare hospitals but we were surprised by the magnitude of the variations. Therefore, we designed this study to identify factors that contributed to the differences. The hospitals, their patient populations, structures and activity levels were similar but we found differences in the training, the review procedures and the experience of the review teams.

Other studies have also found variation of harms across hospitals. Naessens et al18 in a study of 1138 admissions to three academic health centres in three states of the USA found a variation of harms by hospital between 23.1% and 37.9% of admissions. In a study of surgical harms, the variation was between 5% and 35%,26 Sharek et al27 observed harm rates between 0.18 and 1.28 per patient in 749 admissions to 15 newborn intensive care units in the USA and Canada and Resar et al28 in 62 intensive care units in the USA measured between 3.2 and 27.36 harms per 100 days. Thus, significant variations of GTT findings seem to be common.

Several factors could explain the variation in rates of harm. First, there can be differences in the safety of the clinical processes at the hospitals. However, it seems unlikely that such differences should cause as much as a 2.5-fold variation of harm rates given the similar patient populations at the five hospitals and the homogeneity of the Danish healthcare system in general. We even found that the hospital with the highest mean age and the highest hospital standardised mortality rate had the lowest rate of harms. Second, the documentation of triggers and harms probably varies across hospitals. High PSI reporting rates are generally considered a sign of a mature safety culture rather than of poor safety and one could speculate that staff is more likely to document harms in a hospital with such a culture. Also different types of patient records (electronic and paper) and differences in layout and presentation could influence the results of the reviews. We do not have data to explore these questions but we certainly cannot exclude an influence on the different harm rates across hospitals. Third, differences in the training and the experience of the review teams influence the subjective process of judging harms in any record review.12 The team that found the most harms was the most experienced review team and had attended two training seminars. This team was also stable and reviewed regularly with the whole team present twice a month. Finally, the teams conducted the review processes in slightly different ways. Most importantly, the roles of nurses and physicians varied. The role of the physician in the review team that found the highest harm rate was to judge in cases of disagreement while physicians in the other teams themselves identified harms. We assume that nurses are more prone to register harms of lower severity, while physicians might consider them insignificant. This interpretation is supported by our finding that the variation of harm rates was greatest in the least severe category ‘E’.

Thus, in our opinion, the experience of the GTT teams and the way they perform the reviews strongly contributed to the differences in harm rates in the five hospitals. Moreover, differences in the documentation of harms in the patient records seem to influence the number of harms the GTT team can find. We did not expect these factors to be so important because the GTT was implemented according to current recommendations15 17 and was guided by some of their authors. Moreover, all the teams had attended a GTT network meeting with national and international experts and received site visits by a national expert. However, these precautions, it seems, were not sufficient to secure at standardised reviewing process at the hospitals. Thus, users of the GTT and its results, healthcare personnel, administrators, payers or the public, should be aware of the challenges of the implementation of the method and allow for sufficient training and evaluation of the results. Our findings also stress that GTT findings should guide hospitals in their efforts to improve patient safety but the results should not be used to compare hospitals.

Strengths, limitations and further research

The strength of this study is its relevance for the implementation of the GTT that increasingly is being used to monitor the safety in hospitals. Our contextual data are detailed and thus practical. The limitations are inherent to the observational nature of the study that prevents conclusions on causal links between the variations of harm rates and the observed differences in team training and review processes. For the same reason, we cannot quantify the contribution of the different factors. Nevertheless, the findings are plausible and fit with the recommendations for the use of the method.15

Further research should address how teams’ reviewing experience and training influence team performance and how team training can be optimised. Moreover, studies should investigate the influence of changes of documentation and presentation of information in patient charts and the use of the types of harm for improving patient safety.

In conclusion, differences in training, review processes and documentation probably have contributed to variations in rates of harm as measured by the GTT. Thus, healthcare staff and policy makers should be aware of the need for systematic training of the review teams and standardisation of the review process when implementing the GTT in new settings. These factors are related to the implementation of the GTT reviews and are not inherent to the method as such. Our study has implications for the implementation of the method in other settings and we suggest considering the following interventions to improve the implementation of the GTT in new settings:

Secure that the review team is trained as a team.

Specify the roles of the reviewers during the reviews to avoid overestimation/underestimation of especially harms of lesser severity depending on professional background.

Test review teams’ abilities to find harms with a set of training charts to estimate their ‘sensitivity’ before routine monitoring is instituted.

Define a minimum number of patient charts that the team should have reviewed before monitoring harms routinely.

Perform reviews with all team members present.

Ensure a structured review process, that is, a space where the team can work without interruptions, regular time intervals between reviews to keep team ‘in shape’.

Implement a common database with individual patient data to allow for re-examination of reviewed charts to avoid problems such as sampling errors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

GTT teams at the five hospitals: Hilleroed: Lisbeth Dammegaard, Anne Marie Kodal, Minna Nielsen, Anne Marie Schlüter, Mette Østergaard. Horsens: Inge-Lise Johansen, Tina Kjær Pedersen, Tom Krintel Petersen, Kiss Ruben Larsen. Kolding: Helle Guldborg Nielsen, Lynge Kirkegaard, Pernille Kølholt Langkilde, Pernille Lennert, Anita Pedersen, Pia Schrøder Petersen. Naestved: Arne Cyron, Helle Fugl, Kim Garde, Annette Knakkergaard, Nina Pedersen, Trine Zachariassen. Thy Mors: Connie Elbeck van der Koij, Mona Kyndi, Mie Landbo, Bente Ringgaard, Hans-Jörg Selter, Lisbeth Thomsen Project managers at the five hospitals: Anne Balle Larsen, Søren Brogaard, Marianne Frandsen, Mona Kyndi Pedersen, Kirsten Løth Lysdahl, Søren Schousboe Laursen, Maria Staun, Inge Ulriksen.

Footnotes

Contributors: CvP, JA and AMK designed the study and collected data. CvP drafted the manuscript, JA and AMK revised and approved. JA performed the statistical analyses and produced the graphs.

Funding: CvP received a grant from the Danish Society for Patient Safety to write this article.

Competing interests: CvP leads the current Safer Hospital campaign at one of the participating hospitals. AMK is a member of the GTT review team at the same hospital. JA is an advisor to the patient safety campaign at the national level. None has any financial interests related to this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.de Vries EN, Ramrattan MA, Smorenburg SM, et al. The incidence and nature of in-hospital adverse events: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:216–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berwick DM, Calkins DR, McCannon CJ, et al. The 100 000 lives campaign: setting a goal and a deadline for improving health care quality. JAMA 2006;295:324–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benning A, Dixon-Woods M, Nwulu U, et al. Multiple component patient safety intervention in English hospitals: controlled evaluation of second phase. BMJ 2011;342:d199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benning A, Ghaleb M, Suokas A, et al. Large scale organisational intervention to improve patient safety in four UK hospitals: mixed method evaluation. BMJ 2011;342:d195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCannon CJ, Schall MW, Calkins DR, et al. Saving 100 000 lives in US hospitals. BMJ 2006;332:1328–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NHS Scotland. Scottish Patient Safety Programme. http://www.patientsafetyalliance.scot.nhs.uk/programme (accessed 11 Mar 2011)

- 7.Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2725–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincent C, Aylin P, Franklin BD, et al. Is health care getting safer? BMJ 2008;337:a2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, et al. Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2124–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dansk Selskab for Patientsikkerhed. The Danish Safer Hospital Programme. 2011. http://www.sikkerpatient.dk/about-sikker-patient/the-danish-safer-hospital-programme.aspx (accessed 11 Mar 2011)

- 11.Sari AB, Sheldon TA, Cracknell A, et al. Sensitivity of routine system for reporting patient safety incidents in an NHS hospital: retrospective patient case note review. BMJ 2007;334:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas EJ, Lipsitz SR, Studdert DM, et al. The reliability of medical record review for estimating adverse event rates. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:812–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buckley MS, Erstad BL, Kopp BJ, et al. Direct observation approach for detecting medication errors and adverse drug events in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2007;8:145–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naessens JM, Campbell CR, Huddleston JM, et al. A comparison of hospital adverse events identified by three widely used detection methods. Int J Qual Health Care 2009;21:301–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffin FA, Resar RK. IHI Global Trigger Tool for measuring adverse events. IHI Innovation Series White paper 2009

- 16.Classen DC, Lloyd RC, Provost L, et al. Development and evaluation of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Global Trigger Tool. J Patient Saf 2008;4:169–77 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adler L, Denham CR, McKeever M, et al. Global Trigger Tool: implementation basics. J Patient Saf 2008;4:245–9 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naessens JM, O'Byrne TJ, Johnson MG, et al. Measuring hospital adverse events: assessing inter-rater reliability and trigger performance of the Global Trigger Tool. Int J Qual Health Care 2010;22:266–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anon Global Trigger Tool. En oversættelse af IHI's værktøj tilpasset danske forhold. Center for Kvalitet, Region Syddanmark, 2008

- 20.Anon Strukturerat journalgranskning för att identifiera och mätta förekomst av skador i vården enligt metoden Global Trigger Tool. Institute for Health Care Improvement Innovation series 2007, Svensk översätning och anpassning. Stockholm: Kommentus Förlag, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabøl LI, Jølving LR, Bjørn B, et al. Systematisk journalgennemgang med IHI's Global Trigger Tool—Erfaringer fra afprøvning i danske sygehuse. Copenhagen: Dansk Selskap for Patientsikkerhed, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anon Patientsikkerhed i kræftbehandlingen—journalgennemgang med Global Trigger Tool. Rapport nr 3/2010. Copenhagen: Kræftens Bekæmpelse, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auerbach AD, Landefeld CS, Shojania KG. The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med 2007;357:608–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perla RJ, Provost LP, Murray SK. The run chart: a simple analytical tool for learning from variation in healthcare processes. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:46–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Classen DC, Resar R, Griffin F, et al. ‘Global trigger tool’ shows that adverse events in hospitals may be ten times greater than previously measured. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:581–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffin FA, Classen DC. Detection of adverse events in surgical patients using the Trigger Tool approach. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:253–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharek PJ, Horbar JD, Mason W, et al. Adverse events in the neonatal intensive care unit: development, testing, and findings of an NICU-focused trigger tool to identify harm in North American NICUs. Pediatrics 2006;118:1332–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Resar RK, Rozich JD, Simmonds T, et al. A trigger tool to identify adverse events in the intensive care unit. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2006;32:585–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.