Abstract

Objective

An area of need in cancer informatics is the ability to store images in a comprehensive database as part of translational cancer research. To meet this need, we have implemented a novel tandem database infrastructure that facilitates image storage and utilisation.

Background

We had previously implemented the Thoracic Oncology Program Database Project (TOPDP) database for our translational cancer research needs. While useful for many research endeavours, it is unable to store images, hence our need to implement an imaging database which could communicate easily with the TOPDP database.

Methods

The Thoracic Oncology Research Program (TORP) imaging database was designed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform, which was developed by Vanderbilt University. To demonstrate proof of principle and evaluate utility, we performed a retrospective investigation into tumour response for malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) patients treated at the University of Chicago Medical Center with either of two analogous chemotherapy regimens and consented to at least one of two UCMC IRB protocols, 9571 and 13473A.

Results

A cohort of 22 MPM patients was identified using clinical data in the TOPDP database. After measurements were acquired, two representative CT images and 0–35 histological images per patient were successfully stored in the TORP database, along with clinical and demographic data.

Discussion

We implemented the TORP imaging database to be used in conjunction with our comprehensive TOPDP database. While it requires an additional effort to use two databases, our database infrastructure facilitates more comprehensive translational research.

Conclusions

The investigation described herein demonstrates the successful implementation of this novel tandem imaging database infrastructure, as well as the potential utility of investigations enabled by it. The data model presented here can be utilised as the basis for further development of other larger, more streamlined databases in the future.

Keywords: Basic Sciences

Article summary.

Article focus

This article highlights a novel tandem thoracic oncology database infrastructure that is designed to capture radiological and histological images for translational research purposes.

To evaluate the utility of this database infrastructure, this article discusses a retrospective investigation into tumour response rates in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma treated with one of two similar chemotherapy regimens.

Key messages

This tandem database infrastructure requires some additional effort to maintain and utilise compared with a single database platform.

The extra effort required for smaller-scale studies is minimal, as demonstrated by our investigation. Moreover, this infrastructure enables more comprehensive translational research.

This data model can serve as a potential example for the development of databases that unify and streamline workflow, enabling larger-scale studies.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study was limited by a small sample size (n=22).

The study suffered from a lack of standardisation: patients received a varying number of chemotherapy cycles and post-treatment CT scans were not always acquired at the same time point.

Tumour response measurements were not acquired according to Modified RECIST.

Introduction

Imaging is an integral tool in oncology, aiding clinicians in diagnosing malignancies, determining appropriate therapies and assessing treatment response. In order to maximise the utility of cancer imaging, the oncology and imaging communities have devoted significant resources to developing informatics tools that allow both clinicians and researchers to store, utilise and share cancer images in more effective ways.1–5 Despite these efforts, there remain areas of need in cancer imaging. One of these deficit areas is the ability to efficiently store and utilise images as a part of collaborative translational cancer research. Consequently, we sought to develop a relational database infrastructure that (1) integrated proteomic, genomic and imaging data; (2) was easily and efficiently created, used and adapted with little to no need for coding and (3) could be acquired by collaborators at negligible cost.

Prior to the initiation of this effort, the Thoracic Oncology Research Program (TORP) at the University of Chicago Medical Center (UCMC) had implemented the Thoracic Oncology Program Database Project (TOPDP) database for our translational research efforts.6 Because the TOPDP database uses Microsoft Access as its underlying technology, it is technically capable of storing images. However, Access databases can only store up to 2 GB of data, so the TOPDP database does not meet our imaging storage demands. To meet this need, we designed and implemented the TORP imaging database using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database platform, which was developed by researchers at Vanderbilt University and made available to UCMC by the University of Chicago Center for Research Informatics (CRI). Due to limitations of REDCap discussed below, our TORP imaging database was not meant to replace our TOPDP database; rather, it was meant to be utilised in conjunction with the TOPDP database.

In the following paper, we evaluate the potential of utilising the TORP imaging database alongside our TOPDP relational database. We demonstrate proof of principle using a retrospective study investigating malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) patient tumour measurements in patients treated with either of two analogous chemotherapy regimens. While this paper will exclusively discuss MPM, it is our hope that this paper will be of general interest to oncology-related informatics as a whole.

Background: MPM

MPM is a deadly disease that affects nearly 3000 new patients annually in the USA.7 In at least 70% of cases, the disease develops secondary to asbestos exposure, with a median latency period of 20–40 years.7 MPM is an extremely difficult disease to treat, and median overall survival (OS) ranges between 6 and 17 months, depending on histological subtype.8 Currently, the standard chemotherapy agents for MPM are the antifolates, pemetrexed and raltitrexed.9 While pemetrexed was shown to induce moderate response (14.1%) as a single agent, it demonstrated considerably higher activity (41.3% response) when used in conjunction with cisplatin.10 11 Cisplatin is sometimes poorly tolerated, especially in older patients, but it can be substituted with carboplatin, a cisplatin analogue which has a reduced toxicity profile.9 Similar activity has been observed between cisplatin-pemetrexed and carboplatin-pemetrexed (26.3% response vs 21.7%, respectively).12 Imaging is critical in MPM cases because it is the primary means of assessing tumour response to treatment, which often correlates to such variables as patient quality of life and OS. Currently, CT is the standard imaging modality used to assess tumour response; it can be supplemented with fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), PET/CT and MRI.13

Materials and methods

Human subject protection

All subjects signed a written consent for at least one of two UCMC Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols. One is a prospective tissue-banking study that allows researchers to bank and analyse tissue from patients treated at UCMC for a thoracic malignancy. The other allows for the study of tissue which has already been collected. Although no tumour tissue analysis was performed for the present study, both protocols also allow for the abstraction of medical information and images from the patients’ charts.

Database security measures

Both the TOPDP and TORP databases include the protective measures necessary to ensure that they meet regulatory requirements instituted by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Security Rule and HIPAA Privacy Rule.14 15 Microsoft Access databases do not automatically have these protective measures in place, but the TOPDP database has been amended using optional Access security features and Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) scripts to meet HIPAA regulations for databases. In particular, access to the database is restricted to an approved list of users, username and passwords are required when opening the database, the database is encrypted, and an audit trail has been created to track changes and user access. Additionally, data can be automatically deidentified before export. REDCap has inherent security measures: only approved users are given access; different users are assigned different levels of access, depending on their research needs; username and password are required; an audit trail records the time, nature and author of a change to the database; and fields marked as identifiers can automatically be excluded when data are exported. Lastly, embedded protected health information (PHI) within images was anonymised by the University of Chicago Human Imaging Research Office (HIRO).16

Informatics infrastructure

The TOPDP database contains demographic, clinical, follow-up, proteomic and genomic data for over 3000 patients with various thoracic malignancies. It is a relational database composed of a master Patients Table and subsidiary tables linked to the Patients Table via a field containing the patient's medical record number. Currently, subsidiary tables contain genomic and proteomic data, but new tables can be designed as needed. Related tables can be queried to display desired variables in a new table.

The Patients Table contains demographic and clinical data, as well as data regarding social, environmental and family history. These variables follow the national standard for oncology databases established by the NCI Common Data Elements Committee, but they extend beyond standard variables to meet needs specific to the Thoracic Oncology Program.17 Not all variables of interest are contained in the patients’ medical charts; consequently, it is necessary to obtain data via a patient interview. Following the patient interview, unknown or unreported variables are abstracted from the patient's medical chart, which is also used to crosscheck patient-reported data for quality assurance purposes. Data are subsequently imported into the TOPDP database.

The TOPDP database is used not only to give a comprehensive view of all consented patients and related research performed by the lab but also to identify smaller cohorts of patients for new research projects in the context of the currently existing IRB protocol. The Patients Table is designed to give general knowledge of patient demographics, history and oncology care. For example, the database captures whether or not a patient has received chemotherapy and the names of the chemotherapy agents the patient has received. However, it does not capture information regarding the number or timing of chemotherapy cycles. When more detailed patient information is required for an investigation, it is abstracted from the patient's medical chart and imported into the TOPDP database in a subsidiary table.

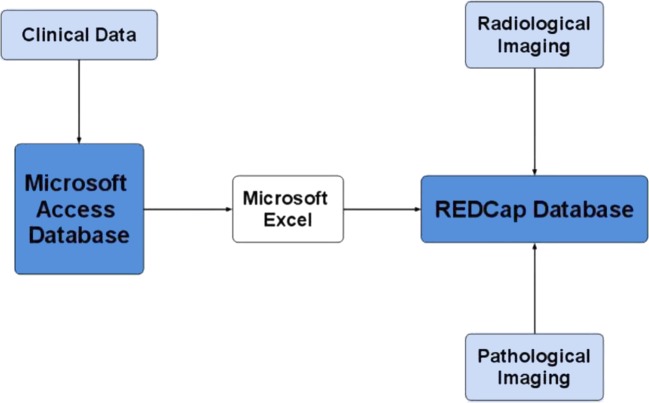

In most cases, the TOPDP database also stores the data required for hypothesis validation after the data are generated or collected. However, in some instances, the TOPDP database is insufficient, as when large files must be stored as part of the study. In this case, the TORP database can be used alongside the TOPDP database. Identical tables are created in both databases, data in the TOPDP database are transferred into the TORP database, and the TORP database is augmented with uploaded files (eg, images). Figure 1 presents a chart detailing this informatics infrastructure.

Figure 1.

Mind map illustrating the relationships between the databases utilised for this project.

Utilisation of databases for MPM study

Subjects were included in this retrospective study if they met the following criteria: (1) they were diagnosed with MPM, (2) were subsequently treated at UCMC with two or more cycles of either carboplatin-pemetrexed or cisplatin-pemetrexed and (3) had a baseline CT scan acquired before their first chemotherapy cycle and a follow-up scan acquired after their second cycle. The TOPDP database was used to identify a cohort of previously consented qualifying MPM patients. Specifically, the Patients Table was filtered to display patients with MPM who had received chemotherapy and who had CT scans acquired at UCMC. However, additional data (number and dates of CT scans and chemotherapy cycles) were required to verify that patients met the selection criteria. These data were abstracted from the patients’ medical charts and then entered into a subsidiary table in the TOPDP database. A similar table was then created in the TORP imaging database. Both tables were identical, with the exception that the TORP database table also contained file upload fields, which were used to capture pretreatment and post-treatment CT section images and histological images. To ensure that data were transferred correctly and easily, fields were given the same names in both databases. Data were transferred from the TOPDP database to the TORP database using a Microsoft Excel comma-separated values (csv) spreadsheet as an intermediary. Images were uploaded into the TORP database using REDCap's online file uploader. Data were exported to Microsoft Excel for analysis.

Data elements and imaging

For each patient, demographic, exposure (to known MPM risk factors) and clinical data relevant to MPM were captured. Many of these data (eg, histology, stage, treatments received, imaging acquired, vital status, etc) are routinely captured. Variables of interest not routinely collected (eg, number, date(s) and type(s) of surgeries and chemotherapy cycles; number and date(s) of CT scans; response to treatment) were abstracted from patient charts.

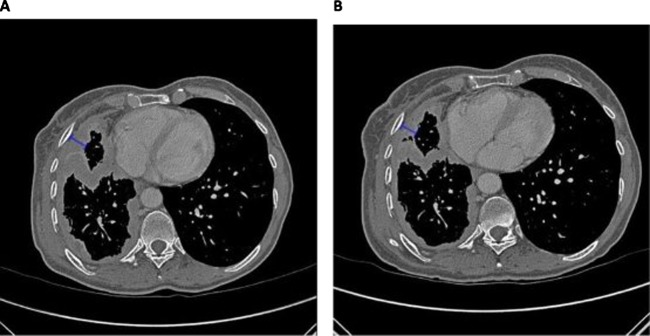

As histology is integral for prognosis in MPM,8 histological images were selected and supplied to the research team by the UCMC pathology department. Three types of images were selected: low-power images, medium-power images and images with immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining. Patients had between 0 and 35 images. Finally, two CT images for each patient were obtained and uploaded into the database: a representative section image from a baseline pretreatment CT scan and an anatomically matched section image from a follow-up CT scan acquired according to clinical protocol. Follow-up images were selected from scans acquired immediately after the second cycle of treatment. If no scan was acquired immediately after cycle two, the next available scan after the second cycle of treatment was selected. While the Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) dictates that tumour thickness be measured at two pleural lesions on three different slices at least 1 cm apart,18 it was felt that since this study was performed as a demonstration, only one pretreatment and one post-treatment measurement were necessary to show proof of principle. Sample pretherapy and post-therapy CT section images are presented in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Example of measurement of CT scan images from a single patient. (A) CT scan image precycle 1 of chemotherapy. Pleural thickness pretreatment was 13.3 mm. (B) CT scan image postcycle 2 of chemotherapy. Pleural thickness post 2 cycle of treatment was 9.19 mm.

Scans used for research purposes were obtained by UCMC's HIRO from the Department of Radiology's clinical image archive. After images were anonymised by the HIRO, a study investigator selected representative sections for pleural measurement. Measurement of pleural thickness was performed using a radiology software package called Abras, which was developed in-house. Abras is image–visualisation interface software that offers tools for image annotation, measurement and contouring and enables the extraction of a wide-range of image-based quantitative and statistical data. It provides users with a high degree of versatility in the interaction with, and manipulation of, medical images. Abras was developed to provide a cross-platform tool to rapidly access, view and evaluate images in support of medical imaging research projects.

Results

Database results

Using the TOPDP database, 129 consented patients with MPM were identified. Twenty-two patients met the selection criteria. For these 22 patients, data were captured in the TOPDP database and subsequently transferred to the TORP database. Patient pretreatment and post-treatment CT scans were assessed, tumour measurements were recorded and representative images were stored in the TORP database. Histological images were also captured.

Specific results from the study itself are detailed below. It is important to emphasise that tumour measurements were not acquired in accordance with Modified RECIST18 and were only acquired at two time points. Consequently, these tumour measurements cannot be considered valid data from which to draw clinical conclusions. They are included here, nevertheless, as an example of the kind of results enabled by utilising this informatics infrastructure.

Example results enabled by utilization of the TOPDP and TORP databases to assess tumor response

Patient characteristics

Of the 22 patients, 21 were men and 1 was woman. Twenty were Caucasian and two were African-American. Ages ranged from 47 to 80 years, with a median age of 65 years. Eighteen patients endorsed prior occupational and/or paraoccupational asbestos exposure; two patients reported unknown exposure and two patients did not have data regarding asbestos exposure recorded in the TOPDP database or their electronic medical records (EMRs). Sixteen patients were diagnosed with epithelial mesothelioma, two with sarcomatoid mesothelioma and four with mixed-type mesothelioma. Eighteen patients underwent one or more surgeries: three patients underwent extrapleural pneumonectomy, three underwent pleurodesis, six underwent pleurectomy/decortication and a further six underwent pleurodesis followed by pleurectomy/decortication. Eleven patients were assessed by the clinician as having an ECOG performance status of 0 at their initial appointments, eight received a score of 1 and three patients were given a score of 2.

Chemotherapy response

Fourteen patients received 2–4 cycles of carboplatin-pemetrexed and eight patients received 4–6 cycles of cisplatin-pemetrexed. Overall, 1 patient received two cycles, 5 patients received three cycles, 11 patients received four cycles, 2 patients received five cycles and three patients received six cycles of chemotherapy. Based on the measurements generated for this study, the mean percentage change in pleural thickness for carboplatin-pemetrexed patients was –25%, indicating a 25% reduction in pleural thickness between the time points of the two CT scans, compared with –11% for cisplatin-pemetrexed patients. Of the 14 patients who received carboplatin-pemetrexed, 9 (41%) remain alive 6–28 months after the start of the chemotherapy. Of the eight patients who received cisplatin-pemetrexed, 4 (50%) remain alive at 16–27 months after start of the chemotherapy. A brief summary of patient characteristics and tumour measurements is presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and tumour measurements

| Number of cases (%)* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entire patient pool | Carboplatin-pemetrexed | Cisplatin-pemetrexed | |

| Total cases | 22 (100) | 14 (100) | 8 (100) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 21 (95) | 14 (100) | 7 (88) |

| Female | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (13) |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 17 (77) | 11 (79) | 6 (75) |

| African-American | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 2 (25) |

| Unspecified | 3 (14) | 3 (21) | 0 (0) |

| Histology | |||

| Sarcomatoid type | 2 (9) | 2 (14) | 0 (0) |

| Epithelioid type | 16 (73) | 11 (79) | 5 (63) |

| Mixed type | 4 (18) | 1 (7) | 3 (38) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||

| Median | 65 | 68.5 | 58.5 |

| Range | 47–80 | 49–80 | 47–75 |

| Performance status | |||

| 0 | 11 (50) | 9 (41) | 2 (9) |

| 1 | 8 (36) | 3 (14) | 5 (23) |

| 2 | 3 (14) | 2 (9) | 1 (5) |

| Vital status at time of study | |||

| Alive | 13 (59) | 9 (64) | 4 (50) |

| Deceased | 9 (41) | 5 (36) | 4 (50) |

| Pleural thickness | |||

| Percentage change | |||

| Mean | −20 | −25 | −11 |

| Median | −19 | −18 | −19 |

*Due to rounding, percentages may not sum to 100.

Discussion

Informatics has been an important part of cancer research efforts to develop more effective diagnostics and therapeutics. These initiatives have led to better clinical outcomes for many patients.19 20 However, prognosis for many patients, including those with MPM, remains poor.19 20 Consequently, it is imperative that we continue researching novel therapeutics to combat cancer as its incidence rises worldwide. To ensure that such research continues, we must develop informatics infrastructures that meet research needs, one of which is an easily implementable comprehensive translational research database capable of handling imaging.

Relational databases that incorporate imaging have been developed by other groups,3–5 but they differ from ours in a fundamental way: ease of implementation. For example, the eDiaMoND database is designed to aid clinicians and researchers by compiling mammography and related clinical data;3 the Biomedical Image Metadata Manager (BIMM) allows researchers to access and query images and associated metadata;4 and the Pathology Analytic Imaging Standards (PAIS) data model database enables the storage and analysis of large TMA datasets.5 All three of these databases are developed based on published data models that can be replicated by outside groups. While implementing one of these databases might be beneficial for some, they are sophisticated enough that we feel it would require a dedicated informatics specialist to replicate them. Consequently, we felt the need to design a simpler informatics infrastructure that incorporated imaging but did not focus on it and that would be more easily implemented by translational research groups without special informatics expertise.

To do so, we decided to use a ready-made database platform that required little to no coding. Unfortunately, widely available, readymade database platforms are often designed to meet a variety of research needs, but rarely ever do they meet all the needs of a specific researcher. Consequently, it was necessary to utilise a tandem database infrastructure in order to incorporate imaging. Microsoft Access has been a very useful platform for our translational research due to its relational nature, ease of querying, portability, ease of deployment and low cost and ubiquity, which enable collaboration with institutions around the world. These features have allowed us to develop the TOPDP database, a comprehensive thoracic database containing patient demographic, clinical, proteomic and genomic data in a centralised location.6 However, Microsoft Access is not without its problems: in particular, Access databases are limited to a 2 GB footprint. Thus, Access is well suited to capture text-based data, but it is limited when capturing images or other files with a large memory footprint.

For this reason, we developed the TORP database using the online REDCap database platform, which was developed at Vanderbilt University and made available to us by the University of Chicago CRI. Like Microsoft Access, the REDCap platform is well suited to meet some of our research needs, but falls short in other areas. REDCap is not relational, so the decision was made to maintain our comprehensive database in Microsoft Access. However, REDCap allows up to 1 TB of storage space and so is ideal for research projects utilising large files. This capability was especially important for this research project, as multiple representative images from CT scans and histological images for each patient were uploaded into the database. Moreover, REDCap interacts easily with Access, communicating via Microsoft Excel or an API call, and, like Access, REDCap encourages collaboration within and among institutions, as it is web based and available freely.

In addition to facilitating more robust and novel analyses, this database structure also fosters intrainstitutional and interinstitutional collaboration. Microsoft Access is widely available for a minimal cost, and REDCap is available freely online to registered users. Moreover, researchers interested in adopting the Salgia Lab's TOPDP and TORP databases may access the lab's standard operating procedures for its Access21 and REDCap22 databases, which further detail the construction and utilisation of the databases and are freely available on the iBridge network. Only by developing a common infrastructure will we be able to facilitate fast and easy collaboration in MPM research, which will be essential if the global biomedical research community is to overtake this increasingly global disease.

This informatics infrastructure is not without its limitations, however, one of which is that data must be captured via patient report or chart abstraction and then manually entered into the TOPDP database. This process is tedious, subject to error and time-consuming. However, there are plans to automate this process by enabling data to be transferred immediately from the patient's EMR, which will reduce workload and the potential for error considerably. In this investigation, data were transferred easily from the Access database to REDCap using Microsoft Excel as an intermediary and REDCap's data upload functionality. This method was sufficient for the purposes of the present study, but if necessary or desired, it is also possible to automate the data transfer process using the REDCap API. However, images must be uploaded manually using REDCap's online file upload field. The time required to upload images for this investigation was negligible. However, having to upload images manually would most likely be prohibitive of studies involving hundreds or thousands of patients.

Our proof of principle investigation was also limited in various ways, for one by sample size (n=22). As this study was retrospective, it was also limited by a lack of standardization: when possible, we selected a follow-up CT scan acquired immediately after the second cycle of chemotherapy, but for some patients, follow-up CT scans were only available after the third or fourth cycle. Furthermore, some patient data remained unreported because it could not be found in physician notes during chart abstraction. Finally, tumour measurements were not acquired using Modified RECIST, so they cannot be said to be valid data from which we can draw clinical conclusions.

Conclusion

We sought to develop a relational database infrastructure that (1) efficiently incorporated images with proteomic, genomic or other laboratory data; (2)could be implemented, used, and altered easily with little knowledge of coding; (3) and was available to collaborators at minimal cost. At first it seemed ideal to capture all our imaging and laboratory data exclusively in REDCap. However, moving entirely into REDCap would require giving up the relational component of our database infrastructure. Consequently, we developed the TORP REDCap database to be used in tandem with our TOPDP Microsoft Access database. In order to evaluate this informatics infrastructure, we performed an investigation into MPM tumour response to two standard chemotherapy regimens. In large part, our investigation was a success: as intended, we were able to implement a relational database that housed both laboratory and imaging data using database platforms that are available at negligible cost and are easily developed and utilised. However, in the course of the investigation, a limitation to our informatics model became apparent: while the time required to upload images in this investigation was negligible, the fact that images must be uploaded manually would most likely preclude large-scale studies. Consequently, we are now working to implement an SQL database, which will be slightly more complex to develop but will enable us to automate workflow and store imaging and laboratory data in a single relational database. In conclusion, it is to be appreciated that this tandem database infrastructure is a very useful tool for small datasets for both informaticians and non-informaticians. Moreover, one can ultimately envision utilising the data model for this infrastructure as a basis for developing a larger and more streamlined database.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The REDCap project at the University of Chicago is hosted and managed by the Center for Research Informatics and funded by the Biological Sciences Division and by the Institute for Translational Medicine, CTSA grant number UL1 RR024999 from the National Institutes of Health. Also, this work was supported in part by 5R01CA100750-08, 5R01CA125541-05 and 5R01CA129501-04 (RS). EV is supported by ASCO Translational Professorship.

Footnotes

Contributions: GBC, SK and MS drafted the manuscript. GBC, SK, MS, AK and CER were responsible for the design, implementation and maintenance of the TOPDP and TORP databases. ASadiq, TH, EEV, WV, HLK and RS provided clinical knowledge and support. NB, BR, RM and PD provided REDCap support. SGA and AStarkey created the Abras imaging software. SGA acquired radiological measurements and selected representative CT images. AH reviewed pathology slides for each patient and provided the histological images. RS oversaw the development of the databases, as well as the drafting of the manuscript.

Funding: CTSA grant (see acknowledgements for additional information).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Armato SG, III, McLennan G, McNitt-Gray MF, et al. Lung image database consortium: developing a resource for the medical imaging research community. Radiology 2004;232:739–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armato SG, III, Ogarek JL, Starkey A, et al. Variability in mesothelioma tumor response classification. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;186:1000–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd S, Jirotka M, Simpson AC, et al. Digital mammography: a world without film? Methods Inf Med 2005;44:168–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korenblum D, Rubin D, Napel S, et al. Managing biomedical image metadata for search and retrieval of similar images. J Digit Imaging 2011;24:739–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Napel SA, Beaulieu CF, Rodriguez C, et al. Automated retrieval of CT images of liver lesions on the basis of image similarity: method and preliminary results. Radiology 2010;256:243–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Surati M, Robinson M, Nandi S, et al. Proteomic characterization of non-small cell lung cancer in a comprehensive translational thoracic oncology database. J Clin Bioinforma 2011;1:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teta MJ, Mink PJ, Lau E, et al. US mesothelioma patterns 1973–2002: indicators of change and insights into background rates. Eur J Cancer Prev 2008;17:525–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rusch VW, Giroux D, Edwards J, et al. Initial analyses of the IASLC International Database for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (MPM). J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:S322–3 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell NP, Kindler HL. Update on malignant pleural mesothelioma. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2011;32:102–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scagliotti GV, Shin DM, Kindler HL, et al. Phase II study of pemetrexed with and without folic acid and vitamin B12 as front-line therapy in malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1556–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, et al. Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2636–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santoro A, O'Brien ME, Stahel RA, et al. Pemetrexed plus cisplatin or pemetrexed plus carboplatin for chemonaive patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: results of the International Expanded Access Program. J Thorac Oncol 2008;3:756–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang ZJ, Reddy GP, Gotway MB, et al. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: evaluation with CT, MR imaging, and PET. Radiographics 2004;24:105–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office of Civil Rights, U.S. Deptartment of Health and Human Services . Health insurance reform: security standards: final rule. Fed Regist 2003;68:8334–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Office of Civil Rights, U.S. Departmrnt of Health and Human Services Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information: final rule. Fed Regist 2000;65:82462–829 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armato SG, III, Gruszauskas N, MacMahon H, et al. The Human Imaging Research Office (HIRO): advancing the role of imaging in clinical trials. Med Physics 2011;38:3406 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel AA, Kajdacsy-Balla A, Berman JJ, et al. The development of common data elements for a multi-institute prostate cancer tissue bank: the Cooperative Prostate Cancer Tissue Resource (CPCTR) experience. BMC Cancer 2005;5:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byrne MJ, Nowak AK. Modified RECIST criteria for assessment of response in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Oncol 2004;15:257–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, et al. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:212–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thoracic Oncology Research Program Microsoft Access Template. (cited 12/01/2011). http://www.ibridgenetwork.org/uctech/salgia-thoracic-oncology-access-template (accessed 21 Jan 2011)

- 22.Thoracic Oncology Program Database Project REDCap Standard Operating Procedure. (cited 2011 12/01/2011). http://www.ibridgenetwork.org/uctech/salgia-thoracic-oncology-redcap-database-sop (accessed 21 Jan 2011)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.