Abstract

Objective

To show long-term trends of smoking initiation in Great Britain including unanalysed data and assess the impact of early smoking initiation on the lung cancer mortality in later ages focusing on birth cohorts.

Design

Reanalysis of repeated cross-sectional surveys conducted 13 times during 1965–1987.

Setting

Great Britain.

Participants

Men and women aged 16 years and over in each survey.

Primary outcome measures

Smoking initiation for 1898–1969 birth cohorts and lung cancer mortality in 1950–2009.

Results

In men, 1900–1925 birth cohorts showed high smoking initiation (>32%, >50% and >80% at 15, 17 and 29 years old, respectively). Correspondingly, the lung cancer mortality in these cohorts exceeded 1 per 1000 at a young age (50–54 years old). In women, smoking initiation increased clearly from the 1898 cohort to the 1925 cohort (2% to 12%, 4% to 24%, and 13% to 54% at 15, 17 and 29 years old, respectively). Correspondingly, the age at which the mortality exceeded 1 per 1000 became younger (75–79 to 60–64 years old). In both men and women, short-term decreases in initiation were seen from the late-1920s cohorts. Correspondingly, lung cancer mortality decreased. In women, initiation increased again after the mid-1930s cohorts, and mortality increased after they became 60–64 years old.

Conclusions

Clear relationships between smoking initiation and lung cancer mortality across birth cohorts were observed. Countries with rapid increases in initiation in teens should not underestimate the risk in the distant future. Because of the long time lags within cohorts compared with rapid changes in smoking habits across cohorts, age-specific measures focusing on birth cohorts should be monitored.

Keywords: Public Health, Preventive Medicine, Statistics & Research Methods

Article summary.

Article focus

Starting to smoke before 15 years of age greatly increased mortality from lung cancer and other diseases in cohort studies.

Aavailable data concerning smoking initiation and subsequent lung cancer mortality in later age by birth cohort are limited in most countries.

Key messages

The male birth cohorts with high smoking initiation in their teens had high lung cancer mortality, and clear increases in smoking initiation among female cohorts corresponded to the increases in lung cancer mortality.

Short-term decreases in smoking initiation seen from the late-1920s cohorts corresponded to the decreases in lung cancer mortality.

In women, smoking initiation increased after the mid-1930s cohorts, and their lung cancer mortality increased after 60–64 years of age, suggesting a long time lag.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The survey from 1965 in Great Britain provides some of the oldest data about smoking initiation, and the repeated survey about initiation and mortality data in enough scale population provide stable estimates in this study.

The cumulative initiation in this study was based on retrospective questionnaires, and initiation may be underestimated in the elderly.

Introduction

Smoking causes many adverse health effects including lung cancer, cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases.1 Despite its known harmful health effects, almost 1 billion men and 250 million women in the world smoke.2 The tobacco epidemic has shifted to developing countries.1 Furthermore, some countries have experienced a rapid increase in smoking initiation among teens.3 Because there are long time lags between smoking initiation and smoking-attributed mortalities which become apparent only in mid-to-late adulthood, the impacts of early smoking initiation tend to be unclear.

For global public health, it is important to know smoking and subsequent mortality data in several birth cohorts with various smoking habits. However, available data are limited, especially about smoking initiation. In Great Britain, the age of smoking initiation was frequently surveyed between 1965 and 1987,4 but birth cohorts were not specified. In this paper, we quantitatively estimated long-term trends of smoking initiation and showed the relationship to the lung cancer mortality focusing on birth cohorts.

Methods

Smoking initiation

From 1948 to 1987, the Tobacco Advisory Council conducted an annual survey on smoking habits in Great Britain (England, Wales and Scotland).4 Most of these surveys interviewed about 10 000 people. The age of initiation was reported from the 13 surveys conducted in 1965, 1968, 1971, 1973, 1975, 1978 and annually during 1981–1987 as percentages of people who started smoking any tobacco by sex and age group at the time of survey. Age of initiation was categorised as <14 (1975–1987), 14–15 (1975–1987), <16 (1965–1973), 16–17, 18–19, 20–24, 25–29, >29, ‘Don't know’ and ‘Never smoked for as long as a year’ (1965–1987). The percentages of ‘Don't know’ were <5% in women, <6% in men aged <35 years and <11% in older men, and we excluded this category in the analysis. For initiation data, age at the time of survey was categorised as 16–19 (1965–1987), 20–24 (1965–1987), 25–34 (1965–1975), 25–29 (1975–1987), 30–34 (1981–1987), 35–59 (1965–1975), 35–49 (1981–1987), 50–64 (1981–1987), >59 (1965–1975) and >64 (1981–1987). We defined the birth year using the median age or next larger integer; thus, people aged 16–19 years in 1987 were defined as the 1969 birth cohort (1987 minus 18). For the categories >59 and >64, the median age was estimated from population statistics.5 We excluded the data for 35–59 years of age because the range was too wide. We calculated the cumulative proportion of people who began smoking by specified ages. Then, for each birth cohort, except for cohorts that had no observations, we estimated cumulative initiation by taking an average of the data in a time window of 5 years as a smoothing method. For example, cumulative initiation of the 1967 birth cohort is estimated from the average of the data for the 1965–1969 birth cohorts. In the age categories of >59 or >64, cumulative initiation and birth years were estimated by taking an average of data for the periods of 1965–1968, 1971–1975 and 1981–1987. These cover the 1898–1969 cohorts.

Smoking prevalence

To show changes in age-specific prevalence with birth year, we used data from the annual survey of the Tobacco Advisory Council in 1948–1975 and the General Household Survey in 1972–2005 conducted in Great Britain.6 7 Most of the surveys of the Tobacco Advisory Council interviewed about 10 000 people, and the General Household Survey interviewed 12 000 households or more. We used prevalence reported annually for 16–19 and 20–24-year-olds in 1948–1975, and 50–59-year-olds for 18 years during 1972–2005. We used prevalence of all tobacco products except for women in the survey of the Tobacco Advisory Council. For them, we used prevalence of manufactured cigarettes, as few women smoked products other than cigarettes and the prevalence of all tobacco products was not reported for several years. The prevalence included occasional smokers. In the same manner as the smoking initiation, we defined birth year and estimated the average prevalence. These surveys cover the 1917–1987 cohorts.

Lung cancer mortality

We calculated annual lung cancer mortality rates between 1950 and 2009 in Great Britain based on data in England and Wales and data in Scotland from the WHO Mortality Database.5 We used mortality categorised as 5 year age groups from 35–39 to 80–84 years of age. We defined participants who were 80–84 years old in 1950 as the 1868 birth cohort. For each birth cohort, we took an average of the data from the birth cohorts within 1 year. These data cover the 1868–1972 birth cohorts.

Statistical analysis

We showed changes with birth year in the cumulative smoking initiation, smoking prevalence and lung cancer mortality at specified ages. Trends including peaks and troughs in these indicators were assessed. Lung cancer mortality in later ages has been already observed up until the mid-1920s cohorts.

Results

Table 1 shows cumulative smoking initiation by sex and birth cohort. Men in the 1900 cohort, the oldest cohort with available data, showed the highest initiation and the 1900–1925 cohorts showed high initiation (>32%, >50% and >80% at 15, 17 and 29 years old, respectively). Generally, from the 1900 cohort to the 1955 cohort, initiation decreased successively with birth year except for the 15-year-old or younger age group. The oldest cohort for women, the 1898 cohort, showed the lowest initiation. Initiation increased clearly from the 1898 cohort to the 1925 cohort (2% to 12%, 4% to 24%, and 13% to 54% at 15, 17 and 29 years old, respectively). From the 1925 cohort to the 1955 cohort, initiation was stable at 24 and 29 years of age but increased at younger ages.

Table 1.

Cumulative smoking initiation by birth cohort (1898–1965) from the survey of the Tobacco Advisory Council, Great Britain, 1948–1987

| Men |

Women |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative initiation (%) |

Cumulative initiation (%) |

||||||||||||

| Birth | Age (years) |

Birth | Age (years) |

||||||||||

| cohort | 13 | 15 | 17 | 19 | 24 | 29 | cohort | 13 | 15 | 17 | 19 | 24 | 29 |

| 1900 | – | 34 | 58 | 70 | 83 | 86 | 1898 | – | 2 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 13 |

| 1906 | – | 34 | 58 | 70 | 82 | 84 | 1904 | – | 3 | 7 | 10 | 17 | 20 |

| 1913 | 11 | 32 | 51 | 63 | 76 | 80 | 1911 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 17 | 26 | 41 |

| 1925 | 12 | 33 | 51 | 66 | 77 | 80 | 1925 | 2 | 12 | 24 | 36 | 49 | 53 |

| 1935 | – | 23 | 47 | 65 | 74 | – | 1935 | – | 8 | 23 | 37 | 48 | – |

| 1945 | 9 | 29 | 51 | 61 | 68 | 67 | 1945 | 3 | 13 | 32 | 44 | 52 | 52 |

| 1955 | 10 | 29 | 47 | 55 | 59 | 60 | 1955 | 5 | 21 | 38 | 47 | 51 | 53 |

| 1965 | 13 | 32 | 45 | 49 | – | – | 1965 | 8 | 24 | 37 | 44 | – | – |

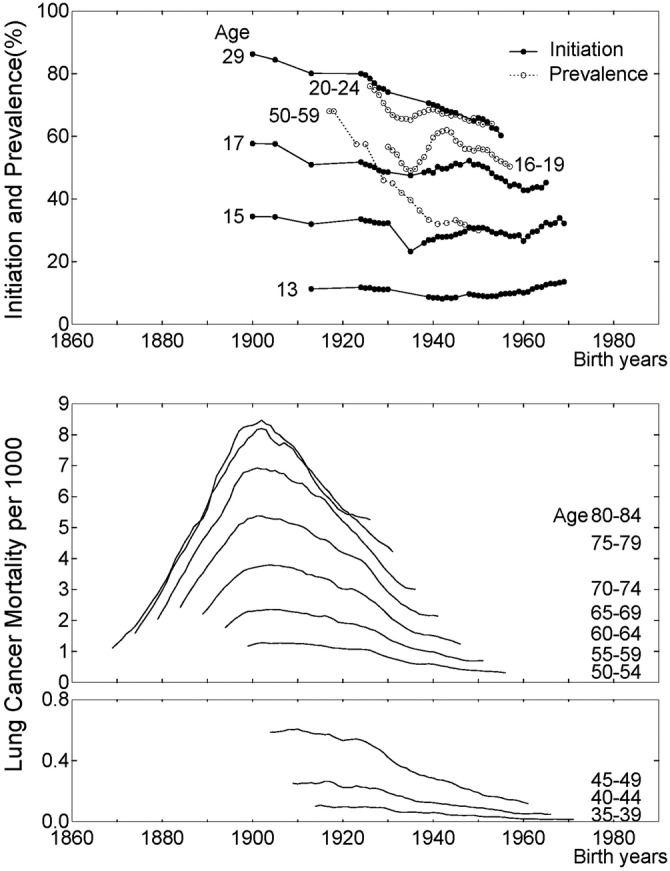

Figure 1 and figure 2 show changes with birth year in cumulative smoking initiation, prevalence and lung cancer mortality by age for men and women, respectively. In men, mortality increased rapidly from the 1870 cohort to the 1905 cohort. In the 1870 cohort, the mortality was already over 1 per 1000 in the 80–84 age group. In the 1900–1925 cohorts, which showed the high smoking initiation, the mortality exceeded 1 per 1000 at younger age (50–54 years old). After the early-1900s cohorts, the mortality decreased, and especially rapid decreases were seen between the late-1920s and the mid-1930s cohorts. Correspondingly, the short-term troughs in initiation and prevalence in 16–19 and 20–24 years old were seen in the mid-1930s cohorts.

Figure 1.

Changes with birth year in cumulative smoking initiation, prevalence and lung cancer mortality by age for British men. Data are from the survey of the Tobacco Advisory Council (TAC) in 1965–1987 for initiation, the survey of the TAC in 1948–1975 and the General Household Survey in 1972–2005 for prevalence, and the WHO mortality database for lung cancer mortality in 1950–2009.

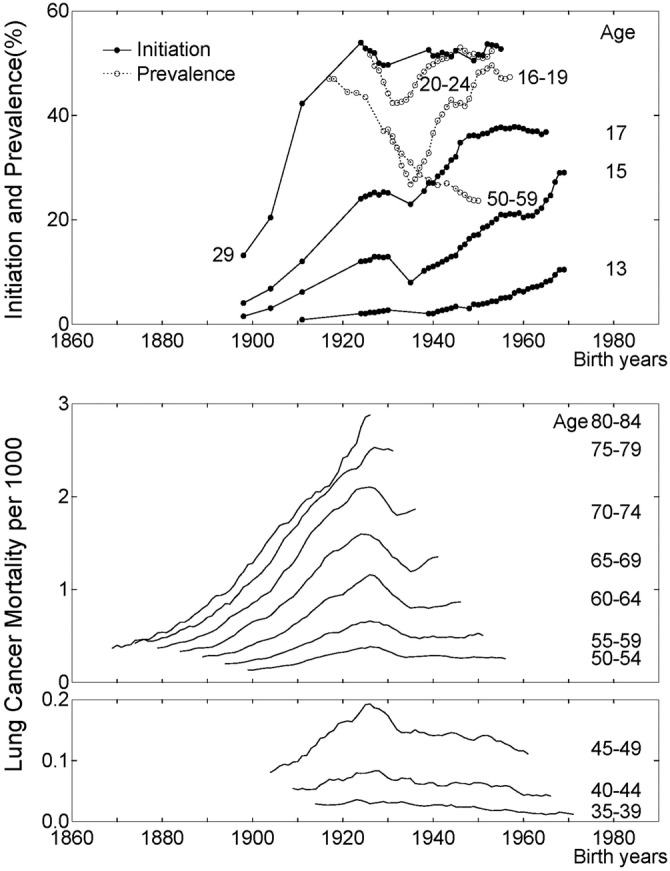

Figure 2.

Changes with birth year in cumulative smoking initiation, prevalence and lung cancer mortality by age for British women. Data are from the survey of the Tobacco Advisory Council (TAC) in 1965–1987 for initiation, the survey of the TAC in 1948–1975 and the General Household Survey in 1972–2005 for prevalence, and the WHO mortality database for lung cancer mortality in 1950–2009.

In women, mortality increased from the 1870 cohort to the mid-1920s cohorts. Up until the early-1890s cohorts, the mortality was below 1 per 1000 even in 80–84-year-olds. From the 1898 cohort to the 1925 cohort, smoking initiation clearly increased (table 1), and the age at which the mortality exceeded 1 per 1000 became younger (75–79 to 60–64 years old). Between the late-1920s cohorts and the mid-1930s cohorts the mortality decreased. Correspondingly, decreases in initiation and prevalence were seen. After the mid-1930s cohort, initiation and prevalence in 16–19 and 20–24 years old increased again, but prevalence in 50–59 years old did not increase. The mortality increased after they became 60–64 years old.

Discussion

In this paper, we quantitatively showed the long-term trends of smoking initiation in Great Britain focusing on birth cohorts. Clear relationships were seen between smoking initiation and lung cancer mortality. The male cohorts with high smoking initiation in their teens had high lung cancer mortality. Clear increases in smoking initiation among female cohorts corresponded to the increases in lung cancer mortality. In women, smoking initiation increased after the mid-1930s cohorts, and their lung cancer mortality increased after 60–64 years of age. This suggests a long time lag between smoking initiation and lung cancer mortality.

Strength and weakness of the study

The age of smoking initiation was surveyed in 1954 in Denmark,8 in 1970 in the USA9 and in some other countries. The survey in 1965 in Great Britain provides some of the oldest data about smoking initiation, and the repeated survey about initiation and mortality data in enough scale population provide stable estimates in this study. The cumulative initiation in this study was based on retrospective questionnaires. In the elderly, cumulative initiation may be underestimated because people who started smoking earlier tended to die younger. Elderly may also report older age of initiation than their actual age of initiation. However, these biases would not change the finding that cohorts with high initiation showed high lung cancer mortality because elderly men showed the highest initiation. Considering the large differences in cumulative initiation across cohorts of elderly women, the possible underestimation would not change the finding that the clear increases of initiation corresponded with the increases in lung cancer mortality. Since 1908, the sale of tobacco to children under the age of 16 has been prohibited. The age rose to 18 in 2007. The cumulative initiation at the age of 15 was about 30% other than around the mid-1930s birth cohorts in men, but it changed largely in women. These suggest that social norms about the smoking were not changed largely in male children, but these were changed in female children. Women under tight social norms might report older age of initiation than their actual age of initiation. However, considering the high cumulative initiation at the age of 24 (about 50%), the social norm would not be so strict compared to some other countries and this possible bias would not change the findings.

Strength and weakness in relation to other studies

Relationships between smoking prevalence in adults and lung cancer mortality have been analysed by various authors.10–12 However, smoking initiation and lung cancer mortality in later life by birth cohort have rarely been presented together regardless of its importance. To interpret the lung cancer mortality of a particular age, we ideally need to know not only smoking in the recent past but also smoking in their teens or 20s.13 Starting to smoke before 15 years of age greatly increases mortality from lung cancer and other diseases.13 14 The duration of smoking is a strong determinant of lung cancer mortality,13 and early smoking initiation is correlated with the duration. Furthermore, earlier smoking initiation may be associated with greater risk because early exposure to tobacco products may enhance DNA damage.15 16 Smoking prevalence in later ages and amounts of smoking also affect lung cancer mortality. There are reports for smoking prevalence in several countries, but data for prevalence in the late 19th and the first half of the 20th century are missing or uncertain. This means that parts of smoking prevalence are missing for the cohorts whose lung cancer mortality in later ages has been already observed. In Great Britain, the age-specific prevalence before 1948 is unclear. In the surveys from 1948, several age categories for the reported prevalence, such as 35–59-year-olds, were too wide to define birth cohorts. Similar to the prevalence, the available data for consumption per smoker by age group are limited.4 The later cohorts showed larger consumption until about the 1950s birth cohorts (see online supplementary figures S1 and S2), but the lung cancer mortality in later ages around these cohorts has not been observed yet.

Unanswered questions and future research

After the mid-1920s cohorts, lung cancer mortality at later ages has not yet been observed. Future data will reveal the impacts of increasing early initiation in women and the combined impacts of high early initiation and decreasing prevalence in men on lung cancer mortality at later ages. These are ecological comparisons, and accumulation of consistent results among countries is desirable. Short-term decreases and increases in prevalence in young men and women occurred between 1948 and early 1960, and the troughs were seen in 1955.4 This pattern of the changes was not seen in older ages. These troughs in 1955 correspond to the troughs seen in the mid-1930s cohorts in figures 1 and 2. Several medical papers about smoking and adverse health effects published in 1950 are a possible reason of the decrease in prevalence of young people. Subsequent controversy of the adverse health effects and the increase of sales of filtered cigarettes are possible reasons of the increase after the mid-1930s cohorts. The differences in prevalence among these cohorts in women were clearer than those in men, and correspondingly the troughs in female lung cancer mortality in 60–64 years old or older were seen. Steep decreases and subsequent unclear decreases were seen in men too. The mortality in later ages has not yet been observed. In both men and women, increases were not seen in the prevalence in 50–59 years old between the mid-1930s and the early-1940s cohorts. A possible reason is that the age at which smokers start to quit has decreased in later cohorts, so that the prevalence in later ages was lower in later cohorts.

Smoking cessation greatly reduces mortality.12 17–19 Based on a prospective cohort study among male British doctors, if people stop smoking before 30 years of age the risk almost disappears.17 However, it is unclear that the result can be generalised to those who started smoking from a very young age. It is also unclear as to whether mortality later in life is the same level as in non-smokers.

Tobacco use causes many other adverse health effects. Especially global mortality from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is high.1 In Great Britain, the mortality from COPD showed similar trends with lung cancer mortality (see online supplementary figures S3 and S4). In men, the mortality was high in the older cohorts and decreased with birth year. In women, the mortality increased clearly until the mid-1920s cohorts, and then decreased. Compared to the lung cancer mortality, increases in mortality with age were larger over 75–79 years old. More comprehensive studies about adverse health effects caused by tobacco use are desirable.

Implications for clinicians and policymakers

Monitoring is one of policies against the tobacco epidemic.1 Because this study showed the long time lag between smoking initiation and lung cancer mortality within cohorts compared with possible rapid changes in smoking habits across cohorts, age-specific measures focusing on birth cohorts should be monitored. A repeated cross-sectional nationwide survey is suited to obtain long-term population data.20 21 The results should be reported by age so that birth cohorts can be specified. If age categories have the same intervals, birth cohorts can be easily specified. In a cohort, cumulative smoking initiation tends to increase steeply with age, so the initiation age should be reported by detailed categories.

For cohorts born in the 19th century, smoking initiation and lung cancer mortality at younger ages were unclear even in this study. Lung cancer mortality is used as an indicator of past smoking habits due to its strong relationship to smoking.22 Lung cancer mortality in non-smokers was less than 1 per 1000 even at 80–84 years of age.23 Based on the WHO mortality database,5 lung cancer mortality in a birth cohort has rarely exceeded 1 per 1000 at 45–49 years old or 10 per 1000 even at 80–84 years old to date, with few exceptions. The mortality from lung and pleural cancer in England and Wales from 1911 was reported.24 From the late-1860s to the mid-1880s cohorts of men in England and Wales, the age at which the mortality from lung and pleural cancer exceeded 1 per 1000 quickly became younger (from >79 to 55–59 years old). Considering these values, male 1900s cohorts experienced one of the highest lung cancer mortality and probably one of the worst smoking habit. In the early 1900s, lung cancer was a rare disease.25 Most men in the 1900s cohorts started smoking in their teens. In the mid-1970s, over a half century later, the age-standardised male lung cancer mortality peaked in England and Wales.25

The great majority of smokers begin to use tobacco before the age of 18 in most countries.26 However, most data about smoking initiation have been collected in recent decades and/or from developed countries. There are large differences in smoking initiation across birth cohorts in a country and across countries. For example, in Japan, smoking by minors under 20 years of age has been banned since 1900, and male lung cancer mortality has been relatively low (exceeded 1 per 1000 at 60–64 years old or older) in spite of high smoking prevalence. Countries with rapid increases in smoking initiation in teens should not underestimate the risk in the distant future and should take swift action to prevent smoking and to promote early cessation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: IF designed the study, acquired and analysed the data, and prepared the manuscript. TF advised on the analysis and interpretation and commented on the drafts of the manuscript. EY commented on the drafts of the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data and were involved in drafting the manuscript. IF is the guarantor.

Funding: This work was funded by Grant in Aid for Scientific Research (C) (80407931 to IF) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement:No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2008: The MPOWER package. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackay J, Eriksen M. The tobacco atlas. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang G, Fan L, Tan J, et al. Smoking in China: findings of the 1996 National Prevalence Survey. JAMA 1999;282:1247–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wald N, Nicolaides-Bouman A. UK smoking statistics. 2nd edn London and Oxford: Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine and Oxford University Press, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization The detailed data files of the WHO Mortality Database, 2010. http://www.who.int/whosis/mort/download/en/index.html (accessed 7 May 2012)

- 6.Forey B, Hamling J, Lee P, et al. International smoking statistics. A collection of historical data from 30 economically developed countries. 2nd edn Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002:647–88 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forey B, Hamling J, Hamling J, et al. International smoking statistics, web edn. A collection of worldwide historical data, United Kingdom. Surton: P N Lee Statistics and Computing Ltd., 2009. http://www.pnlee.co.uk/ISS.htm (accessed 21 Jul 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osler M. Smoking habits in Denmark from 1953 to 1991: a comparative analysis of results from three nationwide health surveys among adult Danes in 1953–1954, 1986–1987 and 1990–1991. Int J Epidemiol 1992;21:862–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burns DM, Lee L, Shen LZ, et al. Cigarette smoking behavior in the United States. In: Burns DM, Garlfinkel L, Samet J. Smoking and tobacco control monograph No. 8. Bethesda: Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health, National Cancer Institute, 1997:13–112 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Townsend JL. Smoking and lung cancer: a cohort data study of men and women in England and Wales 1935–70. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 1978;141:95–107 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens RG, Moolgavkar SH. A cohort analysis of lung cancer and smoking in British males. Am J Epidemiol 1984;119:624–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.IARC IARC handbooks of cancer prevention, tobacco control, Vol. 11: Reversal of risk after quitting smoking. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doll R, Peto R. The causes of cancer: quantitative estimates of avoidable risks of cancer in the United States today. J Natl Cancer Inst 1981;66:1191–308 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirayama T. Life-style and mortality: a large-scale census-based cohort study in Japan. Basel: Karger, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiencke JK, Thurston SW, Kelsey KT, et al. Early age at smoking initiation and tobacco carcinogen DNA damage in the lung. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:614–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiencke JK, Kelsey KT. Teen smoking, field cancerization, and a ‘critical period’ hypothesis for lung cancer susceptibility. Environ Health Perspect 2002;110:555–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, et al. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case-control studies. BMJ 2000;321:323–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, et al. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ 2004;328:1519–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Rosner BA, et al. Smoking and smoking cessation in relation to mortality in women. JAMA 2008;299:2037–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Funatogawa I, Funatogawa T, Yano E. Do overweight children necessarily make overweight adults? Repeated cross sectional annual nationwide survey of Japanese girls and women over nearly six decades. BMJ 2008;337:a802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Funatogawa I, Funatogawa T, Nakao M, et al. Changes in body mass index by birth cohort in Japanese adults: results from the National Nutrition Survey of Japan 1956–2005. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:83–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, et al. Mortality from tobacco in developed countries: indirect estimation from national vital statistics. Lancet 1992;339:1268–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thun MJ, Henley SJ, Burns D, et al. Lung cancer death rates in lifelong nonsmokers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98:691–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacMahon B, Trichopoulos D. Epidemiology principles and methods. 2nd edn Boston: Little, Brown Company, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quinn M, Babb P, Brock A, et al. Cancer trends in England and Wales 1950–1999. Studies on medical and population subjects No. 66. London: The Stationery Office, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shafey O, Dolwick S, Guindon GE. The tobacco control country profiles. 2nd edn Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc., World Health Organization, and International Union Against Cancer, 2003 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.