Abstract

Objective

To evaluate and compare the effectiveness and tolerability of preoxygenation with the self-inflating bag-valve-mask (BVM) and non-rebreather mask (NRM) as are used before emergency anaesthesia.

Design

Device performance evaluation.

Setting

Experimental study.

Participants

12 male and 12 female healthy volunteers (age range 24–47) with no history of clinically significant respiratory disease.

Interventions

End-expiration oxygen measurements (FEO2) after 3 min of preoxygenation with BVM (without mechanical assistance) and NRM devices. Mask pressures were measured and subjective difficulty of breathing was also assessed with a visual analogue score (VAS).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The final FEO2 achieved was 58.0% (SD 7.3%) for the NRM compared to 53.1% (SD 13.4%) for the BVM (p=0.072). Preoxygenation was associated with small increases in FECO2 that were greater for the BVM (0.50%; 95% CI 0.48 to 0.52) than the NRM (0.29%; 95% CI 0.31 to 0.28); this difference was statistically significant (p=0.028). Both devices were well tolerated on VAS assessment of difficulty of breathing although this was higher for the BVM than the NRM (median VAS 1.85/10 compared to 1.1/10; p=0.041). Inspiratory and expiratory mask pressures were higher for the BVM.

Conclusions

In healthy volunteers, the NRM performs comparably to the BVM in terms of the degree of denitrogenation achieved although neither performed well. Although it was well tolerated, the BVM was subjectively more difficult to breathe through and was associated with greater mask pressures and a small increase in FECO2 consistent with hypoventilation or rebreathing. Our results suggest that preoxygenation with the NRM may be a preferable approach in spontaneously breathing patients.

Keywords: Accident & Emergency Medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

Preoxygenation is an important safety procedure before emergency anaesthesia and aims to prevent hypoxia in the event of prolonged apnoea.

The self-inflating bag-valve-mask (BVM) is commonly used for preoxygenation when an anaesthetic circuit is not available, such as in the prehospital environment.

Recently the use of non-rebreather masks (NRM) as an alternative has become common to avoid increased work of breathing but the effectiveness of this approach has not been formally evaluated.

Key messages

The BVM and NRM are comparable techniques in terms of the degree of denitrogenation achieved.

The BVM is well tolerated but subjectively more difficult to breath through than the NRM, which may lead to reduced patient compliance. Therefore, the NRM may be a reasonable alternative.

By comparison with the existing literature, however, neither technique is as effective as the use of a traditional anaesthetic circuit.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Generalisation of the results from healthy volunteers in an optimal environment to critically ill patients in a suboptimal environment is difficult.

Our results are likely to represent a ‘best case’ upper bound to device performance in combative, critically ill or obtunded patients where effective preoxygenation would be expected to be further compromised.

Emergency anaesthesia is a high-risk intervention, particularly when undertaken in an environment outside of the operating theatre or emergency department such as the prehospital environment where available resources may be suboptimal. Preoxygenation before induction of anaesthesia is an important safety procedure and aims to replace residual nitrogen in the lungs with oxygen. The denitrogenation of the functional residual capacity provides a reserve oxygen store which may transiently prevent arterial oxygen desaturation even during prolonged apnoea1 as might result in the event of a difficult tracheal intubation. Preoxygenation is particularly important in circumstances where securing the airway is predicted to be difficult or where artificially ventilating a patient without a properly secured airway may be dangerous, such as in emergency anaesthesia and/or in patients at risk of aspiration. The critically ill may be both particularly prone and sensitive to rapid arterial oxygen desaturation making optimal preoxygenation before emergency anaesthesia even more important.

A common procedure utilised clinically involves 3 min of tidal breathing from a high oxygen concentration source, that is, through a tightly fitting mask connected to an anaesthetic circuit that prevents rebreathing of CO2. The performance of such anaesthetic circuits has been extensively evaluated. Measurement of end expiratory oxygen fraction (FEO2) gives an estimate of the degree of denitrogenation and therefore the adequacy of preoxygenation. Optimal preoxygenation increases the FEO2 to approaching 90%.2 Other studies have demonstrated that extending the period of preoxygenation beyond 3 min does not lead to a clinically significant improvement in denitrogenation.3 4

In some situations, most notably in the prehospital environment, anaesthetic breathing circuits are less available. In the absence of an anaesthetic circuit, the self-inflating bag-valve-mask (BVM) device is often used5 as it is readily available, can still provide ventilation with air in the event of oxygen supply failure and can be used for both preoxygenation or to assist breathing. However, the BVM may increase resistance to passive breathing and feel claustrophobic. Gentle assistance with breathing using light pressure on the BVM can overcome this but, if not carefully performed, could also cause stomach distension in semiconscious patients, increasing the risk of aspiration.

As a possible alternative, a number of investigators have examined whether effective preoxygenation can be delivered with a standard oxygen face-mask (‘Hudson’ mask), which is less tightly fitting and therefore well tolerated.4 6 7 Results from these studies have shown that the degree of denitrogenation achieved is inferior with the Hudson mask. This is due to air entrainment around the mask during inspiration, which occurs because peak inspiratory flow may be far greater than the rate at which oxygen can be practically supplied from cylinders.

High-flow non-rebreather masks (NRM) are similar to traditional Hudson masks but additionally incorporate a simple valve system so that peak inspiratory flow demand may be met with oxygen from an attached reservoir bag rather than air entrained through leaks around the mask. These masks are now commonplace in hospitals and in the prehospital setting and are almost always initially applied to patients who are critically ill. In principle, the presence of a reservoir bag should improve the effectiveness of these devices for preoxygenation and therefore they may offer a safe and potentially better-tolerated alternative to the BVM. On this basis, the practise of using an NRM for emergency preoxygenation is becoming increasingly widespread. However, to date, there has not been a study comparing these two methods and air entrainment may still be significant compared to a cushioned mask.8 In this study, we compare the efficacy of the BVM and the NRM for preoxygenation and the ease of breathing with each mask in volunteers.

Methods

Volunteer group

The study was reviewed and approved by the local ethical review board (NRES Committee East of England—Cambridge Central, study 12/EE/0057). A total of 24 healthy volunteers were recruited from hospital staff by advertisement. The volunteers had a working association with the investigators but no organisational involvement in the study. Volunteers with acute respiratory disease or receiving treatment for chronic respiratory disease, including asthma, were excluded. Pregnancy, body mass index of greater than 35, known or suspected coronary or cerebrovascular disease and previous exposure to bleomycin were also exclusion criteria. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study design

The study was conducted with the subjects in the fully supine position. Each subject was preoxygenated for 3 min by normal tidal breathing with each mask in turn and the procedure repeated (ie two attempts with each mask with the results averaged). An oxygen flow rate of 10 l/min was chosen for both the BVM and NRM and this was sufficient that the reservoir bag remained well filled at end inspiration in all cases. Thus, at this flow rate, free supply of oxygen to meet peak inspiratory flow without avoidable entrainment should have been available. FEO2 and FECO2 measurements were made before and after each mask was tested by slow end expiratory reserve exhalation into a mouthpiece connected to a calibrated gas analyser (Datex-Ohmeda S/5, GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK). The subjects breathed room air between each set of observations until the end expired samples had returned to baseline composition.

The starting mask was predetermined by block randomisation so as to eliminate a systematic error from ‘training’ effects. There are two sizes of BVM commonly used in our unit. Half the subjects were randomly allocated to a 1.5 litre BVM the other half tested with a 1 litre BVM with pressure relief valve (type 7152 and 7153, respectively, Intersurgical Ltd, Berkshire, UK). An appropriate anaesthetic mask, chosen by the investigators, was used (type 1515 or 1516, Intersurgical Ltd, Berkshire, UK). Subjects were instructed to apply the BVM tightly onto their face so that there was no leak and the investigators monitored this. The NRM (type 1102, Intersurgical Ltd, Berkshire, UK) was securely fitted by the investigators by adjustment of elastic headband and nose clip.

To ascertain the resistance to breathing added by each of the devices, a pressure transducer was placed inside the mask. For the BVM, a manometer line connected to a standard invasive blood pressure transducer (Ref T445211B, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, Califonia, USA) was positioned under the seal of the mask. The line was sufficiently thin as to not disrupt the seal. For the NRM the manometer line was attached to a blunt needle inserted through the mask body adjacent to the nose clip. Our pressure recording equipment recorded maximum and minimum mask pressures to the nearest mmHg.

Finally, subjects were asked to subjectively evaluate each of the masks using a visual analogue scale with zero representing ‘normal breathing’ and 10 representing ‘almost impossible to breathe’.

The primary outcome measure was the end expiratory oxygen concentration after breathing through the mask for 3 min. The secondary outcome measure was the ease of breathing through each mask as indicated by the pressure measurements and visual analogue scale assessment. Changes in breathing pattern could be partially assessed from the end expiratory carbon dioxide (FECO2) results before and after using the mask.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using R (version 2.15.0). Two-tailed tests were employed throughout. Student's t test was used for parameters where there was no evidence of non-normality (Shapiro-Wilks test). Otherwise, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used: p values were estimated using a 1000 repetition Monte Carlo ‘jitter’ method to allow for ties. A statistical significance of 5% was assumed. Using the literature 2–4 9 to estimate the likely variability in FEO2. The sample size was chosen to have at least 80% power to detect a 10% difference in FEO2 (corresponding approximately to a clinically significant increase in oxygen reserve of 1 min) at the 5% significance level.

Results

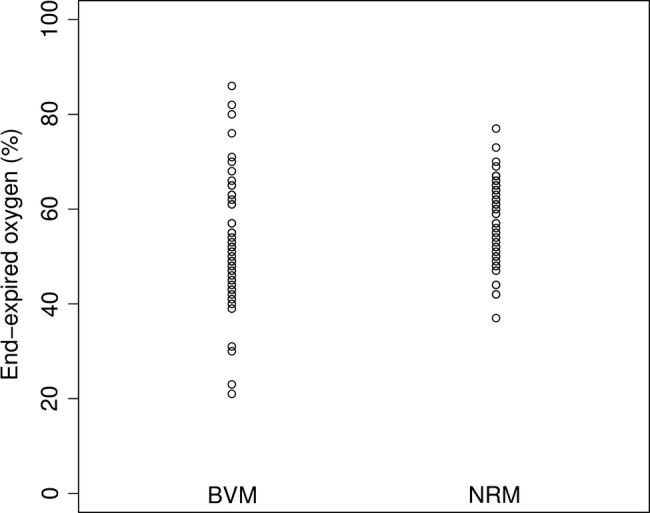

The subject characteristics are summarised in table 1. Mean measured FEO2 after preoxygenation with a BVM and NRM was 53.1% (SD 13.4%) and 58.0% (SD 7.3%), respectively (figure 1) (p=0.072, paired t test). The FEO2 achieved after preoxygenation did not differ significantly between large and small BVMs (p=0.58, unpaired t test).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Subject characteristic | Range |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 22–47 |

| Sex | 12 male, 12 female |

| Height (m) | 1.6–1.88 |

| Weight (kg) | 52–95 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 19.10–28.08 |

| Smoking history (N/ex-smoker/Y) | 17/6/1 |

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of FEO2 after preoxygenation for the bag-valve-mask (BVM) and non-rebreather masks (NRM) devices.

Baseline FECO2 measurements were comparable between BVM and NRM groups. Preoxygenation was associated with small increases in FECO2 that were greater for the BVM (0.50%; 95% CI 0.48 to 0.52) than the NRM (0.29%; 95% CI 0.31 to 0.28) and this difference was statistically significant (p=0.028).

The maximum recorded positive expiratory pressure was 1 mm Hg for the BVM but unrecordable with our equipment for the NRM (p=0.016, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Maximum negative inspiratory pressure was up to −3 mm Hg for the BVM and −2 mm Hg for the NRM (p<0.001, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

The median visual analogue scale rated difficulty in breathing was 1.85/10 (range 0–7.2/10) for the BVM compared to 1.1/10 (range 0–5.9/10) for the NRM (p=0.041, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Discussion

Overall, we have shown that the NRM and BVM were comparable in terms of the degree of denitrogenation achieved. While the final FEO2 achieved was 4.9% greater for the NRM than the BVM, this difference was not statistically significant. While the average FEO2 achieved with the BVM was comparable with the NRM, the spread in the data was greater.

Our values of FEO2 achieved after BVM preoxygenation were somewhat lower than those achieved in Stafford et al,9 who found the mean FEO2 to be 74.2%. However, we measured FEO2 at the end of an expiratory reserve breath rather than sampling end tidal gas from the mask, and this is likely to be higher due to mixing and incomplete exhalation which may account for the discrepancy. We believe our method is a more accurate measure of true end-alveolar oxygen and the actual degree of oxygen reserve obtained.

There was a statistically significant difference between the maximum and minimum mask pressures generated with the NRM and BVM (around 1–2 mm Hg given the limited resolution of our monitor). This implies a greater resistance to breathing with the BVM and, while small, is not insignificant compared to the normal pressure changes seen in eupnoea and could become important in the case of dyspnoea. That the FECO2 was higher after preoxygenation could be due to either partial rebreathing or hypoventilation. However, the increased airway pressures and subjective difficulty in breathing shown by the visual analogue scale data might give credence to the latter explanation. While the increase in FECO2 may not be clinically significant, any additional resistance to breathing is clearly undesirable and likely to reduce tolerance in anxious, disorientated or combative patients.

While it would appear that in a prehospital or emergency setting, the BVM and NRM are similarly effective, it is worth pointing out that comparison of our data with the literature confirms that both underperform an anaesthetic circuit9 for preoxygenation. It is common clinical experience that mask-sampled (tidal breathing) FEO2 levels approach 80 or 90% after 3 min preoxygenation with a Bain or circle system.

Our study has a number of potential limitations. One potential weakness in the study design is the integrity of the seal created by the subjects holding the BVM on themselves. However, it was felt that tightly holding a mask onto a healthy volunteer was likely to cause discomfort, which may have led them to radically alter their breathing or even withdraw from the study altogether. To mitigate this, the participants were clearly instructed to hold the mask firmly and avoid leaks and the investigators visually monitored this. In most cases, mild blanching of the skin under the mask was visible. Irrespective of this, it seems unlikely that the seal with a cushioned mask and therefore the potential for air entrainment would have been significantly worse than for the NRM design. The BVM has a valve arrangement, which may allow room air to enter the system if mask pressures are sufficiently negative and while we have not evaluated the performance of this or the effect of mask dead-space, and it is conceivable that any of the above factors may have contributed to the greater variability in average FEO2 seen with the device. At the same time it is important to remember that firm application of an anaesthetic mask to dyspnoeic or otherwise confused/obtunded patients typically increases agitation and often makes maintaining an airtight seal difficult. So, while we cannot exclude the possibility of small leaks in our volunteer study, it is doubtful if this can ever be the case in the emergency situation either.

Another limitation of the study is that critically ill patients are unlikely to have a normal breathing pattern. They may have reduced or increased minute volume as well as a reduced or increased respiratory volume. Therefore, the levels of preoxygenation achieved with the BVM and NRM may exceed the efficacy in a critically ill patient: that is, our study is likely to represent a ‘best case’. Clearly, the BVM offers the potential for ventilatory support, which the NRM does not.

In conclusion, there was no significant difference between the efficacy of preoxygenation with a BVM or an NRM. The NRM was associated with lower mask pressures in normal ventilation and was subjectively better tolerated. Its use for preoxygenation is simple although clearly it is imperative to confirm that all equipment, including a method for ventilation, be immediately available and functioning before anaesthesia is induced. Although inferior, the BVM can still be well tolerated and offers the option of assisting ventilation, which is also an important consideration in emergency care. Comparison with previous published results suggests that both devices are inferior to an anaesthetic circuit and the use of such a purpose-designed system which is valveless and has minimal resistance to flow is therefore to be encouraged wherever possible. Our results, however, emphasise the limited safety margin available in emergency anaesthesia.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The authors were jointly responsible for the planning, design, running and analysis of the study as well as the preparation of the manuscript. AE conceived the study and was the principal investigator.

Funding: This study received no funding.

Competing interests: None.

Data sharing statement: The authors will share non-identifiable original experimental datasets with academics for bona fide scientific purposes on written application.

References

- 1.Sirian R, Wills J. Physiology of apnoea and the benefits of preoxygenation. Cont Educ Anaesth, Crit Care Pain 2009;9:105–8 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirsch J, Führer I, Kuhly P, et al. Preoxygenation: a comparison of three different breathing systems. Br J Anaesth 2001;87:928–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCrory JW, Matthews JN. Comparison of four methods of preoxygenation. Br J Anaesth 1990;64:571–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hett DA, Geraghty IF, Radford R, et al. Routine pre-oxygenation using a Hudson mask. A comparison with a conventional pre-oxygenation technique. Anaesthesia 1994;49:157–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weingart S. Preoxygenation, reoxygenation, and delayed sequence intubation in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2011;40:661–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ooi R, Pattison J, Joshi P, Chung R, Soni N, et al. Pre-oxygenation: the Hudson mask as an alternative technique. Anaesthesia 1992;47:974–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maurette P, O'Flaherty D, Adams AP. Pre-oxygenation: an easy method for all elective patients. Eur J Anaesthesiol 1993;10:413–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Standley T, Smith H, Brennan L. Room air dilution of Heliox given by facemask. Intens Care Med 2008;34:1469–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stafford RA, Benger JR, Nolan J. Self-inflating bag or Mapleson C breathing system for emergency pre-oxygenation? Emerg Med J 2008;25:153–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.