Abstract

Objective

To assess short-term differences in population mental health before and after the 2008 recession and explore how and why these changes differ by gender, age and socio-economic position.

Design

Repeat cross-sectional analysis of survey data.

Setting

England.

Participants

Representative samples of the working age (25–64 years) general population participating in the Health Survey for England between 1991 and 2010 inclusive.

Main outcome measures

Prevalence of poor mental health (caseness) as measured by the general health questionnaire-12 (GHQ).

Results

Age–sex standardised prevalence of GHQ caseness increased from 13.7% (95% CI 12.9% to 14.5%) in 2008 to 16.4% (95% CI 14.9% to 17.9%) in 2009 and 15.5% (95% CI 14.4% to 16.7%) in 2010. Women had a consistently greater prevalence since 1991 until the current recession. However, compared to 2008, men experienced an increase in age-adjusted caseness of 5.1% (95% CI 2.6% to 7.6%, p<0.001) in 2009 and 3% (95% CI 1.2% to 4.9%, p=0.001) in 2010, while no statistically significant changes were seen in women. Adjustment for differences in employment status and education level did not account for the observed increase in men nor did they explain the differential gender patterning. Over the last decade, socio-economic inequalities showed a tendency to increase but no clear evidence for an increase in inequalities associated with the recession was found. Similarly, no evidence was found for a differential effect between age groups.

Conclusions

Population mental health in men has deteriorated within 2 years of the onset of the current recession. These changes, and their patterning by gender, could not be accounted for by differences in employment status. Further work is needed to monitor recessionary impacts on health inequalities in response to ongoing labour market and social policy changes.

Keywords: Social Medicine, Public Health, Epidemiology, Mental Health

Article Summary.

Article focus

Previous studies have found differing impacts of recession on mental health, with some deteriorations in health outcomes (such as suicide) being worse in men than women.

Few studies have investigated mental health morbidity and its patterning by population subgroups over prolonged periods of time.

We assess short-term changes in population mental health and inequalities (by gender, age and socio-economic position) following the recent recession, by placing it in a longer historical context.

Key messages

Population mental health in men has deteriorated within 2 years of the onset of the current recession.

These changes in population mental health, and their patterning by gender, cannot be accounted for by differences in employment status over time.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our study uses a large nationally representative dataset to assess trends over a long length of time and an outcome likely to be sensitive to changes in the macro-economic environment.

We assess trends across a number of dimensions (and measures) of inequality, helping to address an important gap in the current literature.

Establishing causality from this research is difficult given the cross-sectional (rather than longitudinal) nature of the surveys and lack of available data for some time periods.

Introduction

Macroeconomic factors are known to influence population health and health inequalities.1 The onset of the global economic downturn heralded by the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 can therefore be considered as a potential threat to public health.2–4 In the UK, national gross domestic product (GDP) has fallen in real terms (with a 5.5% fall per head of population between 2008 and 2009) and unemployment rates have increased since the recession began.5 Neither indicator has yet recovered to pre-recession levels at the time of writing.6 Unemployment is associated with a number of adverse health impacts including poor mental health, short-term increases in adverse health behaviours and increased mortality risk.7–9 However, the effects of recession appear to be more complex than would be expected from the impact of increases in unemployment alone. For example, there is a growing body of research suggesting that at least the short-term recessions are associated with a faster decline in mortality although some specific causes of death, such as suicide, may rise.10 Thus, mortality impacts of recessions may be more complex than intuition suggests and likely vary by outcome and context.4 7

Less empirical analysis has focused on the effect of recession on trends in population mental health. Macroeconomic change could potentially have a more rapid effect on mental health compared to mortality, particularly for those of working age. Historically, both periods of recession and unemployment appear to have had a greater impact on men compared to women.7 However, it has been suggested that this differential impact may no longer be present as growing female labour market participation may increase their susceptibility to macroeconomic changes.11 12 In addition, it is not clear to what extent changes in health status associated with recessionary periods are mediated purely through changes in labour market status. The UK experienced its first recession since 1991 (defined as two-quarters of negative growth in GDP) in late 2008.13 Unemployment (which is commonly used as a marker of recession that has a more direct effect on health) showed marked increases between 1991–1993 and 2008–2010.

In this paper, we aim to assess short-term changes in population mental health and inequalities (by gender, age and socio-economic position) following the onset of the recent recession by placing it in a longer historical context. We further aim to investigate to what extent any observed associations and their patterning by subgroups can be accounted for by differences in employment status and education level.

Methods

Data sources

We used data from the Health Survey for England, a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of the community dwelling population, conducted annually from 1991 onwards. Survey methodology has been described elsewhere.14–16 Household response rates for the period studied varied from 85% in 1991 to 64% in 2008.

Unemployment rates (available for the whole period) and GDP per head (comparable data available for 1991–2009) for the UK were retrieved to provide context for the interpretation of trends.5 17 In addition, unemployment data for England (available for 1993 onwards) were retrieved and showed similar trends to the UK data.18 These macroeconomic indicators all show marked deterioration between 2008 and 2009; hence we use 2008 as the reference year for comparison.

Population

The general population samples from the Health Surveys for England were used for all analyses. The study population was restricted to participants of a working age, between 25 and 64 years inclusive. Those aged under 25 years were excluded to minimise misclassification of education level. Participants missing any data on age, sex, highest education level, employment status and outcome were excluded from the analysis (5.15% of total sample excluded). We excluded 2918 participants (2.59% of the sample) with foreign/other qualifications as we were unable to categorise their highest educational attainment accurately. We excluded 847 individuals (0.75%) who defined themselves as doing unpaid work for their family, waiting to take up employment or undertaking government training schemes. Results of overall prevalence estimates were similar when those with missing data (apart from the 1.60% missing outcome data) were included. Similar results were also obtained when the population was limited to those aged 25–59 years, to investigate the potential for gender differentials arising from a younger age of retirement among women.

Exposures

Socio-economic position was assessed using highest education level (self-reported) and area-level deprivation. Comparable information on education level was available for every survey year except for 1995 and 1996 and area-level deprivation was available from 2001 onwards. Educational level was coded into four categories: degree-level or equivalent qualifications, A-level or equivalent, General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) or equivalent and no qualifications, while the index of multiple deprivation was coded into quintiles. Participants were asked to self-identify their employment status based on their activity in the previous week before the survey interview. Employment status was coded into six categories: employed, unemployed, unable to work due to ill health, looking after family/maternity care, retired and in full-time education. Equivalised household income (coded into quintiles and in a sensitivity analysis as a continuous variable) was analysed for the years 2000 onwards in an exploratory analysis.

Outcome measures

Mental health was assessed in every survey year except for 1996 and 2007 through the general health questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12). GHQ-12 is a screening tool for anxiety and depression, validated for use in epidemiological studies.19 Respondents scoring 4 or more have a high likelihood of poor mental health and are considered a ‘case’.20

Statistical analysis

For the first stage of analysis, we analysed data for each year separately. Prevalence estimates for GHQ caseness (age–sex standardisation to the WHO European standard population) were calculated for each year, stratified by age, sex, education level and employment status.

In the second stage of analysis, logistic regression analysis was conducted for each year separately to explore any differential patterning in recession years between men and women. To measure the extent of socio-economic inequality in prevalence on a relative scale we calculated the relative index of inequality using a Poisson modelling approach.15

We directly tested the impact of the recent recession in the final stage of the analysis by creating a combined dataset for all years and creating a logistic regression model adjusting for year, age, education level and employment status. Men and women were analysed separately given the effect modification observed between genders and year. A final stage of analysis investigated if equivalised household income helped explain differences in GHQ prevalence before and after the recession.

All analyses were carried out using Stata V.11.2. Weights for non-response (available from 2003 onwards) were used for all analyses. These were scaled to a mean of 1 for each year to allow analysis of the combined dataset. Robust SEs were used to adjust for survey clustering at the area level. Adjusted prevalence differences were derived from the logistic regression models as well as ORs in order to allow comparisons across models to be made on the absolute scale.21

Results

A total of 106 985 participants were included in the main analysis of trends in GHQ caseness (table 1). The sample response rate declined gradually over time, but they were broadly comparable over the most recent years with no marked changes in response rates during the onset of the current recession. There was also socio-economic change with a decline in the percentage of people with no qualifications and an increase in participants with a degree.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Sex (%) |

Age group (%) |

Highest education level (%) |

Employment status in last week (%) |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | M | F | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | Degree | A-level | GCSE | None | Employed | Unemployed | Not working due to ill health | Retired | Looking after home | In education | Sample | Response rate (%) |

| 1991 | 46.7 | 53.3 | 29.8 | 27.5 | 21.8 | 20.8 | 11.8 | 18.7 | 33.4 | 36.0 | 71.9 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 13.1 | 0.5 | 2001 | 85 |

| 1992 | 47.3 | 52.7 | 29.2 | 28.4 | 22.6 | 19.8 | 11.8 | 22.0 | 35.6 | 30.6 | 69.3 | 6.1 | 4.4 | 6.1 | 13.0 | 1.1 | 2484 | 82 |

| 1993 | 47.5 | 52.5 | 29.7 | 26.6 | 24.3 | 19.4 | 12.8 | 21.7 | 33.3 | 32.2 | 70.9 | 6.3 | 4.3 | 5.5 | 12.4 | 0.6 | 10502 | 81 |

| 1994 | 46.7 | 53.3 | 30.2 | 27.3 | 23.1 | 19.5 | 13.0 | 21.9 | 34.4 | 30.7 | 70.9 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 5.8 | 12.4 | 1.0 | 9981 | 77 |

| 1997 | 47.2 | 52.8 | 29.1 | 27.4 | 25.0 | 18.5 | 16.4 | 24.8 | 31.2 | 27.6 | 71.7 | 3.3 | 6.4 | 4.8 | 12.8 | 1.1 | 5377 | 76 |

| 1998 | 46.6 | 53.4 | 28.4 | 27.5 | 25.2 | 18.9 | 16.6 | 24.1 | 33.0 | 26.3 | 73.4 | 2.0 | 6.1 | 5.4 | 11.6 | 1.4 | 9748 | 74 |

| 1999 | 46.9 | 53.1 | 26.5 | 29.0 | 25.6 | 18.9 | 18.0 | 25.0 | 31.1 | 26.0 | 72.3 | 2.3 | 6.6 | 5.1 | 12.3 | 1.4 | 4750 | 76 |

| 2000 | 45.8 | 54.2 | 26.8 | 30.3 | 23.3 | 19.6 | 18.9 | 27.3 | 31.0 | 22.8 | 72.3 | 2.1 | 6.6 | 5.8 | 11.6 | 1.6 | 4982 | 75 |

| 2001 | 45.7 | 54.3 | 24.9 | 29.6 | 25.3 | 20.2 | 19.6 | 26.1 | 32.6 | 21.6 | 73.3 | 2.0 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 10.3 | 1.7 | 9457 | 74 |

| 2002 | 43.4 | 56.6 | 25.7 | 31.8 | 22.7 | 19.8 | 21.0 | 27.9 | 32.7 | 18.5 | 71.4 | 2.1 | 5.6 | 6.0 | 13.6 | 1.4 | 4619 | 74 |

| 2003 | 45.4 | 54.6 | 23.3 | 29.7 | 23.8 | 23.2 | 21.8 | 25.8 | 32.5 | 19.8 | 74.6 | 1.6 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 10.2 | 1.4 | 8982 | 73 |

| 2004 | 43.4 | 56.6 | 22.5 | 29.2 | 23.6 | 24.8 | 23.0 | 25.7 | 29.8 | 21.5 | 73.0 | 1.4 | 5.9 | 7.4 | 10.7 | 1.6 | 4076 | 72 |

| 2005 | 44.8 | 55.2 | 22.5 | 26.6 | 26.5 | 24.4 | 23.6 | 25.9 | 30.1 | 20.5 | 73.8 | 1.7 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 10.6 | 1.4 | 4590 | 74 |

| 2006 | 44.7 | 55.3 | 21.2 | 28.8 | 24.9 | 25.2 | 25.5 | 26.8 | 29.2 | 18.5 | 73.9 | 1.8 | 5.9 | 6.8 | 10.3 | 1.3 | 8605 | 68 |

| 2008 | 44.7 | 55.3 | 22.0 | 27.5 | 25.2 | 25.3 | 25.6 | 28.0 | 28.7 | 17.7 | 74.0 | 2.1 | 5.4 | 7.4 | 9.6 | 1.6 | 9228 | 64 |

| 2009 | 45.6 | 54.4 | 21.7 | 28.8 | 25.0 | 24.6 | 26.4 | 25.6 | 30.9 | 17.0 | 73.4 | 3.1 | 5.5 | 7.4 | 9.0 | 1.7 | 2773 | 68 |

| 2010 | 43.5 | 56.5 | 21.3 | 26.5 | 27.6 | 24.6 | 28.2 | 28.3 | 29.7 | 13.9 | 73.1 | 3.1 | 5.8 | 7.4 | 9.0 | 1.6 | 4830 | 66 |

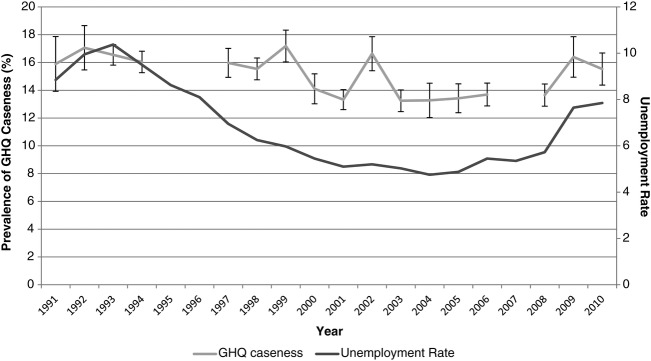

GHQ caseness was relatively high during the time of the early 1990s recession (figure 1). Since then, there has been an indication of a general downward trend with some variability, until a recent increase in prevalence that occurs after 2008. Caseness increased from 13.7% (95% CI 12.9% to 14.5%) in 2008 to 16.4% (95% CI 14.9% to 17.9%) in 2009.

Figure 1.

Overall prevalence of general health questionnaire caseness and unemployment rate 1991–2010.

Impact by subgroups

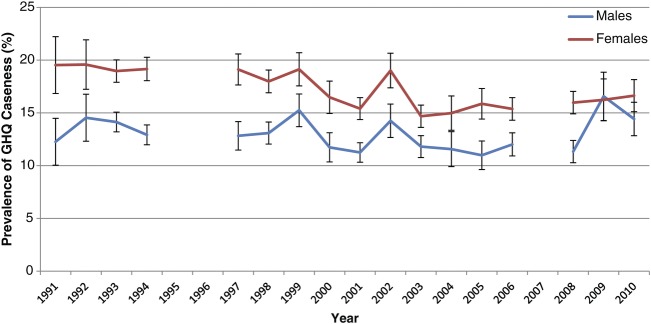

A gender differential in GHQ caseness is apparent; women have a consistently higher prevalence over most of the time period (figure 2). However, during the early 1990s recession, men had a larger increase in prevalence of GHQ caseness from 12.3% in 1991 to 14.5% in 1992. A similar trend is seen following the 2008 recession with an increase from 11.3% to 16.6% in men, compared to 16.0% to 16.2% in women between 2008 and 2009.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of general health questionnaire caseness by gender 1991–2010.

Stratified analysis by age shows that changes in mental health during recessionary periods are not confined to any specific age groups (see online appendix). Sensitivity analysis including those aged 16–24 years showed no clear difference in trends.

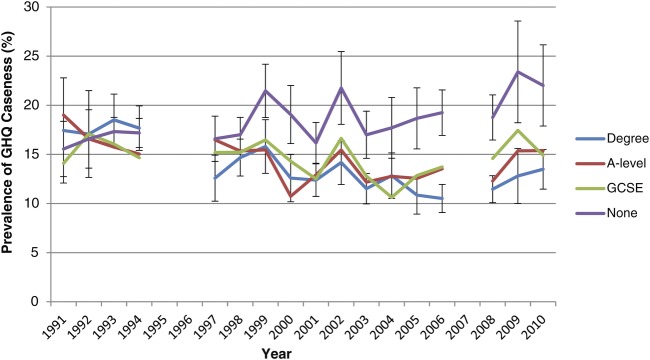

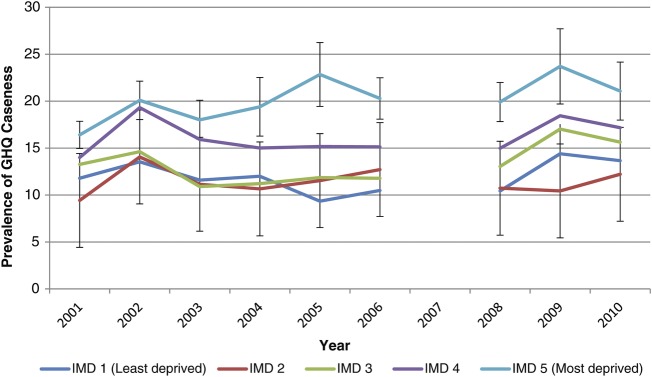

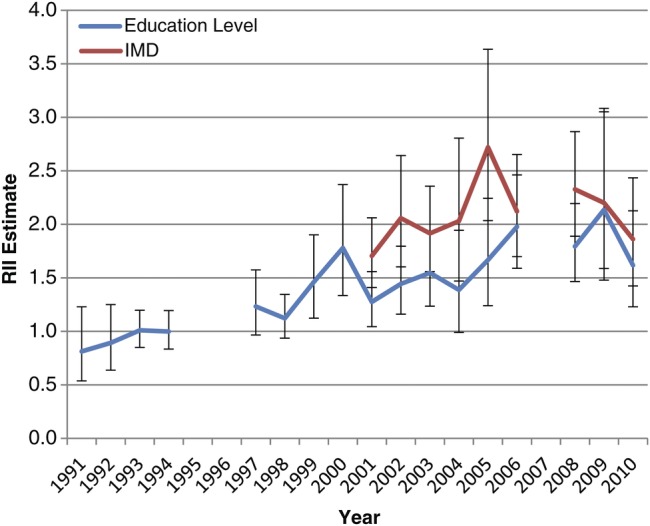

In the early 1990s, stratification by education level reveals an initial reverse education gradient in GHQ caseness (figure 3). Over time, a growing disparity in GHQ caseness between those most and least educated is apparent, with the highest levels of inequality in poor mental health observed in 2005. A similar pattern is seen when assessing caseness by area-level deprivation (figure 4). The greatest levels of relative indices of inequality are also seen since 2005 when assessed by either measure of socio-economic position (figure 5). No significant differences before and after the recession by area-level deprivation are observed.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of general health questionnaire caseness by highest education level 1991–2010.

Figure 4.

Prevalence of general health questionnaire caseness by area-level deprivation (index for multiple deprivation) 2001–2010.

Figure 5.

Relative Index of Inequality (RII) for general health questionnaire caseness as assessed by education level and area-level deprivation (index for multiple deprivation) 1991–2010.

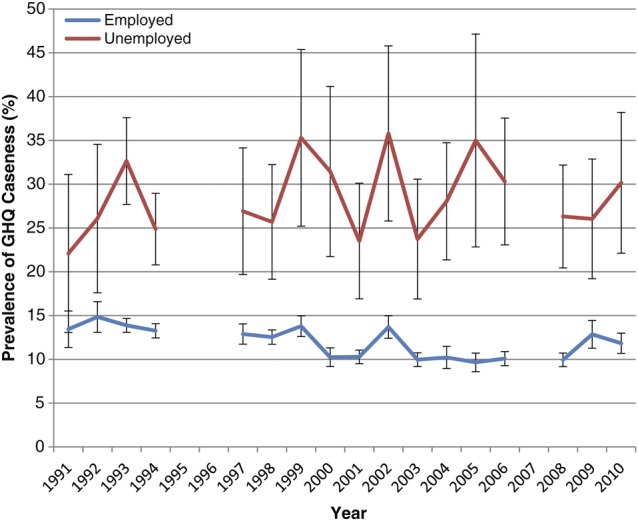

Changes in population mental health do not appear to be entirely mediated by changes in employment status. For example, the prevalence of GHQ caseness among those in employment increased during both recessionary periods: from 13.4% (95% CI 11.4% to 15.5%) to 14.8% (95% CI 13.1% to 16.6%) in 1991–1992 and from 9.9% (95% CI 9.2% to 10.7%) to 12.9% (95% CI 11.3% to 14.4%) between 2008 and 2009 (figure 6).

Figure 6.

General health questionnaire caseness by employment status 1991–2010.

Exploration of the differential trends by gender

A combined dataset for all years was analysed separately for men and women, given the effect modification observed. Compared to a baseline of 2008, age-adjusted caseness increased by 5.1% (95% 2.6% to 7.6%, p<0.001) in 2009 and 3.0% (95% 1.2% to 4.9%, p=0.001) in 2010 among men but no statistically significant changes are seen in women (table 2 and Web tables A–B). Adding employment status to the model suggests that changes in employment status do not explain this increase in poor mental health. Similarly, adjustment for changes in employment status and education level does not account for this increase in prevalence. Finally, adjustment for equivalised household income in a post hoc exploratory analysis also did not explain changes in prevalence (see Web table C).

Table 2.

Analysis of data from 1991 to 2010 in men and women adjusted for age, employment status and education (selected years shown)*

| Model 1: age |

Model 2: age+employment status |

Model 3: age+employment status+education |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | OR | p Value | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | OR | p Value | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | OR | p Value | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

| Male | ||||||||||||

| 2005 | 0.97 | 0.723 | 0.82 | 1.15 | 0.92 | 0.370 | 0.78 | 1.10 | 0.93 | 0.394 | 0.78 | 1.10 |

| 2006 | 1.06 | 0.465 | 0.91 | 1.22 | 1.05 | 0.511 | 0.91 | 1.22 | 1.05 | 0.506 | 0.91 | 1.22 |

| 2008 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| 2009 | 1.53 | 0.000 | 1.26 | 1.86 | 1.50 | 0.000 | 1.24 | 1.82 | 1.50 | 0.000 | 1.24 | 1.82 |

| 2010 | 1.31 | 0.001 | 1.12 | 1.54 | 1.31 | 0.001 | 1.11 | 1.54 | 1.30 | 0.002 | 1.10 | 1.53 |

| Female | ||||||||||||

| 2005 | 1.01 | 0.917 | 0.88 | 1.15 | 1.00 | 0.958 | 0.88 | 1.15 | 1.00 | 0.956 | 0.88 | 1.15 |

| 2006 | 0.96 | 0.467 | 0.86 | 1.07 | 0.95 | 0.342 | 0.85 | 1.06 | 0.95 | 0.344 | 0.85 | 1.06 |

| 2008 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| 2009 | 1.04 | 0.641 | 0.88 | 1.23 | 1.06 | 0.522 | 0.90 | 1.24 | 1.06 | 0.523 | 0.90 | 1.24 |

| 2010 | 1.06 | 0.369 | 0.93 | 1.22 | 1.05 | 0.493 | 0.91 | 1.20 | 1.05 | 0.482 | 0.92 | 1.20 |

| Percentage difference | p Value | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | Percentage difference | p Value | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | Percentage difference | p Value | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | |

| Male | ||||||||||||

| 2005 | −0.31 | 0.722 | −2.02 | 1.40 | −0.75 | 0.367 | −2.12 | 1.32 | −0.71 | 0.391 | −2.34 | 0.92 |

| 2006 | 0.56 | 0.465 | −0.95 | 2.08 | 0.49 | 0.511 | −0.97 | 2.09 | 0.50 | 0.506 | −0.96 | 1.95 |

| 2008 | 0.00 | – | – | – | 0.00 | – | – | – | 0.00 | – | – | – |

| 2009 | 5.07 | 0.000 | 2.60 | 7.55 | 4.54 | 0.000 | 2.67 | 7.65 | 4.52 | 0.000 | 2.21 | 6.83 |

| 2010 | 3.04 | 0.001 | 1.17 | 4.91 | 2.86 | 0.002 | 1.32 | 5.13 | 2.79 | 0.002 | 1.01 | 4.56 |

| Female | ||||||||||||

| 2005 | 0.09 | 0.918 | −1.69 | 1.88 | 0.05 | 0.959 | −1.70 | 1.79 | 0.05 | 0.956 | −1.69 | 1.79 |

| 2006 | −0.55 | 0.467 | −2.04 | 0.94 | −0.70 | 0.341 | −2.13 | 0.74 | −0.69 | 0.344 | −2.13 | 0.74 |

| 2008 | 0.00 | – | – | – | 0.00 | – | – | – | 0.00 | – | – | – |

| 2009 | 0.53 | 0.643 | −1.70 | 2.76 | 0.70 | 0.526 | −1.48 | 2.89 | 0.70 | 0.527 | −1.48 | 2.88 |

| 2010 | 0.84 | 0.372 | −1.01 | 2.70 | 0.63 | 0.495 | −1.18 | 2.43 | 0.64 | 0.485 | −1.16 | 2.44 |

*Reference group is 2008. Selected years around the current recession shown but analyses for all years available in the online appendix.

We attempted to explore the reasons for the adverse changes in the years following the recession among men. When analysing data from each year separately, adjustment for differences in education level and employment status between genders did not account for the larger increase in prevalence among men (see table 3). Therefore, the differing trend in mental health in men appears not to be explained by differing changes in labour market status.

Table 3.

OR and Percentage difference for general health questionnaire caseness by year for women

| Model 1 (age adjusted) |

Model 2 (adjusted for age, education level and employment status) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | OR (95% CI)* | p Value | % difference (95% CI) | OR (95% CI)* | p Value | Percentage difference (95% CI) |

| 1991 | 1.75 (1.40 to 2.20) | 0.000 | 7.34 (4.40 to 10.27) | 1.81 (1.39 to 2.36) | 0.000 | 7.53 (4.30 to 10.75) |

| 1992 | 1.46 (1.16 to 1.84) | 0.001 | 5.31 (2.14 to 8.48) | 1.59 (1.25 to 2.02) | 0.000 | 6.32 (3.10 to 9.54) |

| 1993 | 1.43 (1.29 to 1.57) | 0.000 | 4.87 (3.52 to 6.22) | 1.55 (1.39 to 1.73) | 0.000 | 5.83 (4.37 to 7.30) |

| 1994 | 1.61 (1.45 to 1.78) | 0.000 | 6.32 (4.98 to 7.66) | 1.77 (1.58 to 1.99) | 0.000 | 7.33 (5.90 to 8.76) |

| 1997 | 1.59 (1.38 to 1.84) | 0.000 | 6.17 (4.27 to 8.06) | 1.68 (1.43 to 1.96) | 0.000 | 6.55 (4.62 to 8.49) |

| 1998 | 1.47 (1.31 to 1.64) | 0.000 | 4.98 (3.56 to 6.39) | 1.58 (1.39 to 1.79) | 0.000 | 5.64 (4.15 to 7.13) |

| 1999 | 1.29 (1.11 to 1.50) | 0.001 | 3.59 (1.50 to 5.67) | 1.40 (1.19 to 1.65) | 0.000 | 4.44 (2.30 to 6.59) |

| 2000 | 1.47 (1.24 to 1.73) | 0.000 | 4.63 (2.66 to 6.61) | 1.61 (1.33 to 1.94) | 0.000 | 5.22 (3.19 to 7.26) |

| 2001 | 1.44 (1.28 to 1.62) | 0.000 | 4.19 (2.85 to 5.53) | 1.55 (1.37 to 1.77) | 0.000 | 4.75 (3.38 to 6.13) |

| 2002 | 1.41 (1.21 to 1.64) | 0.000 | 4.73 (2.71 to 6.76) | 1.51 (1.27 to 1.78) | 0.000 | 5.32 (3.19 to 7.45) |

| 2003 | 1.29 (1.14 to 1.45) | 0.000 | 2.91 (1.52 to 4.29) | 1.38 (1.20 to 1.58) | 0.000 | 3.44 (1.99 to 4.88) |

| 2004 | 1.35 (1.11 to 1.63) | 0.002 | 3.37 (1.25 to 5.49) | 1.40 (1.14 to 1.71) | 0.001 | 3.51 (1.38 to 5.65) |

| 2005 | 1.52 (1.29 to 1.80) | 0.000 | 4.85 (2.97 to 6.72) | 1.68 (1.40 to 2.03) | 0.000 | 5.46 (3.57 to 7.35) |

| 2006 | 1.33 (1.18 to 1.49) | 0.000 | 3.29 (1.92 to 4.67) | 1.40 (1.22 to 1.60) | 0.000 | 3.57 (2.18 to 4.96) |

| 2008 | 1.46 (1.29 to 1.65) | 0.000 | 4.41 (3.03 to 5.79) | 1.54 (1.34 to 1.76) | 0.000 | 4.52 (3.11 to 5.94) |

| 2009 | 0.99 (0.79 to 1.24) | 0.927 | −0.15 (−3.26 to 2.97) | 1.09 (0.86 to 1.39) | 0.465 | 1.13 (−1.89 to 4.15) |

| 2010 | 1.19 (1.01 to 1.39) | 0.036 | 2.24 (0.16 to 4.32) | 1.24 (1.04 to 1.48) | 0.016 | 2.63 (0.52 to 4.75) |

*Reference group is men.

Discussion

In this large repeat cross-sectional study of representative samples of the English population, we have found evidence to suggest population mental health has deteriorated in men following the start of the 2008 recession. Notably, this change does not appear to arise only as a result of an increase in unemployment, but mental health appears to have declined among those in employment. Household income also does not account for the observed trend in mental health. While some commentators have recently suggested that the current recession may affect both genders in a similar manner, we find that the deterioration in mental health appears only among men. Furthermore, this differential association cannot be adequately accounted for by changes in employment status (such as greater unemployment) among men. We also find evidence to suggest that socio-economic inequalities (assessed by both highest education level and area-level deprivation) have increased over the course of the last decade, but the recession had not been associated with a widening of socio-economic inequalities in mental health by the year 2010.

Our study has a number of strengths. We used a large nationally representative dataset which used a validated screening test for anxiety and depression. Importantly, we assessed trends over a long length of time with annual measures available for most of the period and an outcome likely to be sensitive to changes in the macroeconomic environment. This allows greater certainty in attribution compared to studies limited to comparisons of single before and after surveys.

As our study makes use of available data, a number of important limitations exist. First, data were not available for every year, with the omission of GHQ in 2007 potentially problematic as this represents the last full pre-recessionary year. Second, we have been limited to repeat cross-sectional analysis. Longitudinal analysis of individuals would allow greater scope for relating changes in individual employment status to health. Third, while we have chosen a validated outcome measure, it is possible that framing effects could account for some of the observed changes. In particular, GHQ items were asked first in the self-completion questionnaire in 1999, 2002 and 2009, all years with a high prevalence. However, the higher prevalence following 2008 among men remains in 2010. Fourth, defining recessionary periods and exploring their effects are notoriously difficult. We have studied changes over time but did not directly incorporate macroeconomic measures into our analysis. In addition, we have only been able to investigate a few of the potential pathways between recession and mental health. Further work is needed to explore other pathways such as temporary employment and increased job insecurity. Lastly, although our study has investigated changes in population mental health associated with the recession, we cannot establish whether this is a causal relationship, as other temporal changes could account for the observed trends. However, many factors that could potentially account for our findings, such as changes in health or social care provision, could also be considered mediating factors rather than confounders.

Much previous research has focused on mortality, and in particular suicide, associated with recession. In an analysis of cause-specific mortality and its association with recession in European countries, Stuckler et al22 found that the most consistently observed relationship was an increase in suicide among young men. Recently, they found that increases in suicide rates have been observed across European countries following the onset of the current recession.23 Consistent increases in male suicide rates have been noted in many other studies.24 The relationships between morbidity in mental health, health inequalities and recessions are less well understood and findings differ between studies.7 25 A recent before and after comparison of patients attending primary care services in Spain found a marked increase in the prevalence of mental health disorders following the onset of the current global recession.26 Household unemployment and mortgage difficulties were particularly associated with these attendances. However, not all studies have found a negative association between economic recession and mental health. For example, Vinamaki et al27 found no statistically significant increase in poor mental health (assessed using GHQ) following the economic recession in Finland between 1993 and 1995 in repeated general population samples.

While our study finds men's mental health has declined while women's has not, it should be noted that important indirect effects of the recession, including changes in the public sector workforce and changes in government assistance for children, had yet to be implemented during the time of this study. Our analysis does not yet show any indication of worsening mental health inequalities associated with the current recession. However, there is a general trend towards a greater level of inequality more recently and there is no evidence to suggest narrowing. Further research will be required to assess ongoing impacts of the recession by gender and socio-economic position. As our analysis was restricted to a working-age population, research focusing on retired individuals is also needed to investigate the potential impact in older age groups. The existing evidence suggests that the relationship between mental health and recessions differs, at least in part, by social welfare system.10 22 28–31 There is therefore a need for cross-national comparisons of trends in population health and health inequalities to better identify social policy responses that protect from any adverse health impacts of recession.

The finding that mental health across the general population has deteriorated following the recession's onset, and this association does not appear to be limited to those out of employment nor those whose household income has declined, has important implications. Previous research has highlighted the importance of job insecurity, rather than solely employment status, as potentially resulting in adverse effects on mental health.32 One potential explanation for our results would be that job insecurity during the current recession is responsible for the deterioration in mental health with men's psychological health remaining more affected by economic fluctuations despite greater female labour market participation. This paper highlights the continuing importance of addressing mental health issues using population-wide approaches by both policymakers and health professionals and not limiting such efforts to those directly affected by unemployment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of the UK Data Archive for providing access to the data; the Information Centre for health and social care and Department of Health for sponsoring the Health Survey for England; and the Principal Investigators of the Health Survey for England, Natcen Social Research and the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health at the Royal Free and University College Medical School. In addition, we would like to thank Geoff Der at the MRC/CSO Social & Public Health Sciences Unit for providing statistical advice. Finally, we would like to thank the reviewers whose comments have improved the article. The responsibility for the analysis presented here lies solely with the authors.

Footnotes

Contributors: SVK acts as guarantor for this article. SVK conceived the idea for the study, led on the analysis and wrote the first draft of the article. CLN and FP assisted in research design, analysis and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: SVK is funded by the Chief Scientist Office at the Scottish Health Directorate as part of the Evaluating Social Interventions programme at the MRC Social and Public Health Sciences Unit (MC_US_A540_0013). FP is funded by the MRC (5TK10). CLN has received no funding for this study. The funders had no influence over the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the paper or decision to submit. The paper does not necessarily represent the views of the funding or employing organisations. SVK had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of analysis.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study is an analysis of previously collected data and therefore ethical approval was not required for this study. Ethical approval for each survey was obtained by the Health Survey for England team.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: : Supplementary files are provided.

References

- 1.CSDH Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health . Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.BBC News Q&A: Lehman Brothers bank collapse. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/7615974.stm (accessed 16 Jan 2012).

- 3.Stuckler D, Basu S, McKee M, et al. Responding to the economic crisis: a primer for public health professionals. J Public Health 2010;32:298–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, et al. The health implications of financial crisis: a review of the evidence. Ulster Med J 2009;78:142–5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrera S, Beaumont J. Income and wealth—Social trends 41. In: Beaumont J, ed. London: Office for National Statistics, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Office for National Statistics GDP and the labour market, 2012 Q1—May GDP update. London, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bambra C. Work, worklessness and the political economy of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bambra C, Pope D, Swami V, et al. Gender, health inequalities and welfare state regimes: a cross-national study of thirteen European countries. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63:jech-070292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roelfs DJ, Shor E, Davidson KW, et al. Losing life and livelihood: a systematic review and meta-analysis of unemployment and all-cause mortality. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:840–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bezruchka S. The effect of economic recession on population health. CMAJ 2009;181:281–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bambra C. Yesterday once more? Unemployment and health in the 21st century. J Epidemiol Community Health 2010;64:213–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minton JW, Pickett KE, Dorling D. Health, employment, and economic change, 1973–2009: repeated cross sectional study. BMJ 2012;344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Office for National Statistics Impact of the recession on the labour market. London, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mindell J, Biddulph JP, Hirani V, et al. Cohort profile: the Health Survey for England. Int J Epidemiol 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aresu M, Boodhna G, Bryson A, et al. Health Survey for England 2010, Volume 2: methods and documentation. Craig R, Mindell J, eds. London: The NHS Information Centre for health and social care. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett N, Dodd T, Flatley J, eds. Health Survey for England 1993: A survey carried out by the social survey division of OPCS on behalf of the Department of Health. London: HMSO, 1995. London, 1995;227–265. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spence A. Labour market—social trends 41. In: Beaumont J, ed. London: Office for National Statistics, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Office for National Statistics Regional labour market statistics, January 2012 London, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, et al. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med 1997;27:191–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg D, Williams P. A user's guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-Nelson, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mood C. Logistic regression: why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. Eur Sociol Rev 2010;26:67–82 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, et al. The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet 2009; 374:315–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, et al. Effects of the 2008 recession on health: a first look at European data. Lancet 2011;378:124–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zivin K, Paczkowski M, Galea S. Economic downturns and population mental health: research findings, gaps, challenges and priorities. Psychol Med 2011;41:1343–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riva M, Bambra C, Easton S, et al. Hard times or good times? Inequalities in the health effects of economic change. Int J Public Health 2011;56:3–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gili M, Roca M, Basu S, et al. The mental health risks of economic crisis in Spain: evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. Eur J Public Health . Published Online First 19 Apr 2012. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cks035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heimo Viinamäki JH, Kontula O, Niskanen L, et al. Mental health at population level during an economic recession in Finland. Nord J Psychiatry 2000;54:177–82 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandra H. Economic stability and health status: evidence from East Asia before and after the 1990s economic crisis. Health Policy 2006;75:347–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stuckler D, Basu S, McKee M. Budget crises, health, and social welfare programmes. BMJ 2010;340:c3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uutela A. Economic crisis and mental health. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2010;23:127–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundin A, Hemmingsson T. Unemployment and suicide. Lancet 2009;374:270–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG, et al. Health effects of anticipation of job change and non-employment: longitudinal data from the Whitehall II study. BMJ 1995;311:1264–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.