Abstract

Objectives

Anti-phosphorylated histone H3 (pHH3) antibodies specifically detect the core protein histone H3 only when phosphorylated at serine 10 (Ser10) or serine 28 (Ser28). Measurement of pHH3 levels can be used for quantifying mitosis and the effectiveness of mitotic inhibitors in early drug development. However, data on the expression level of pHH3 (Ser10) and pHH3 (Ser28) among different cancers are limited. This study was designed to investigate the expression levels of pHH3 across different types of cancers, using uniform techniques and assay platforms in a single laboratory.

Design

Retrospective study.

Setting

Single laboratory.

Specimens

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded various human cancer specimens were provided by Mosaic Laboratories Tissue Bank.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Using immunohistochemistry, pHH3 levels were measured using both pHH3 (Ser10) and (Ser28) antibodies among 10 human melanoma and 10 ovarian tumour samples. The samples were reviewed blindly by two reviewers. pHH3 (Ser10) was then selected to measure the pHH3 levels in cancers of breast, colorectal, oesophageal, gastric, head and neck and lung (n=5 for each cancer).

Results

The pHH3 (Ser10) expression was higher than pHH3 (Ser28) in both melanoma and ovarian cancers (p<0.01), with the mean (SD) levels of 1.28% (0.47%) for Ser10 and 0.53% (0.44%) for Ser28 among melanoma and 3.47% (3.51%) for Ser10 and 0.62% (0.68%) for Ser28 among ovarian cancers, respectively. No statistically significant differences were observed among different cancer types tested for pHH3 using Ser10 (p=0.197). No reviewer effect was identified.

Conclusions

The pHH3 Ser10 was significantly higher than Ser28 and may serve as the more robust of two pHH3 assays for measuring mitotic index.

Keywords: Anaesthetics

Article summary.

Article focus

Immunohistochemical detection of phosphorylated histone H3 (pHH3) is often implemented for monitoring drug-mediated mitotic changes in clinical trials; however, data on the expression level among different cancers are limited.

By comparing the performance of antibodies to pHH3 (Ser10) and pHH3 (Ser28) in the same laboratory and in various cancer specimens, the pHH3 Ser10 was shown to be significantly higher than Ser28 and may serve as the more robust of two pHH3 assays for measuring mitotic index.

Key messages

H3 (pHH3) is often implemented for monitoring drug-mediated mitotic changes in clinical trials; however, data on the expression level among different cancers are limited.

We, for the first time, compared in the same laboratory the performance of two antibodies pHH3 (Ser10) and pHH3 (Ser28), in various cancer specimens.

The pHH3 Ser10 was significantly higher than Ser28 and may serve as the more robust of two pHH3 assays for measuring mitotic index.

Strengths and limitations of this study

At the time this study was performed, there were no data comparing pHH3 levels between Ser10 and Ser28 and pHH3 levels across different types of cancers.

Using uniformed techniques, and assay platforms in a single laboratory, we assessed pHH3 (Ser 10 and Ser 28) expression levels.

No significant difference was observed among different tumour types (p=0.1969 non-parametric testing), which may probably be due to the sample size (n=5 for each).

In addition, we could not perform subgroup analysis and check the variation of pHH3 levels by different demographic, pathology and clinical characteristics. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm the preliminary findings.

Introduction

Microscopic evaluation of mitotic activity is a routine procedure in assessing the grade of malignancy in tumours such as soft tissue sarcoma and breast adenocarcinoma.1 Histone H3 is a core histone protein, which together with the other histones forms the major protein constituents of chromatin in eukaryotic cells. Anti-phosphorylated histone H3 (pHH3) antibodies specifically detect the core protein histone H3 only when phosphorylated at serine 10 (Ser10) or serine 28 (Ser28). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for pHH3 has been used for mitotic cell counting in different types of tumours as marker of cells in late G2 and M Part. Multiple studies have demonstrated strong correlation between pHH3-based IHC and standard mitotic counts performed on samples stained with H&E.1 2 Comparisons between pretreatment and post-treatment pHH3 levels are often used to evaluate the effectiveness of mitotic inhibitors in preclinical in vitro studies and clinical trials.

There is only limited information on the expression level of pHH3 among different types of cancers including breast,1 3 4 ovarian,5 colorectal,6 squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx,7 intracerebral gliomas (primary intracerebral astrocytoma),8 9 meningioma2 10 and granular cell tumours.11 Different phosphorylation sites (ie, Ser10 and Ser28), different antibodies and measurement units (ie, mitotic index, label index and labelling fraction) were used in these studies in different labs, and there were large variations in the pHH3 levels across studies and cancer types. To our knowledge, this study was the first study to investigate the expression levels of pHH3 across different types of cancers, using uniform techniques and assay platforms in a single laboratory.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study was conducted in two parts. The purpose of Part I was to perform IHC using pHH3 (Ser10) and pHH3 (Ser28) antibodies in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) human melanoma, ovarian cancer (10 samples in each cancer type) and differentially treated HeLa cells to evaluate which antibody corresponded to higher expression levels. The purpose of Part II was to perform IHC using the antibody that demonstrated higher expression levels in Part I, in human cancers of breast, colorectal, oesophageal, gastric, non-small cell lung samples (NSCLC) and head and neck and lung (5 in each type). A second evaluation of the per cent positive staining of pHH3 (Ser10) and pHH3 (Ser28) in human melanoma and ovarian cancer were performed blindly to assess the levels of pHH3 from two independent readers.

FFPE human cancers were provided by Mosaic Laboratories tissue bank, and were procured under an Institutional Review Board reviewed protocol. FFPE cell blocks were prepared from differentially treated HeLa cells (ATCC, Manassas, Virginia, USA) in order to address the IHC assay specificity. HeLa cells were either untreated, treated with nocodazole (0.333 μM nocodazole for 18 h) or treated with double thymidine block (1.65 mM thymidine for 18 h, 8 h media, 1.65 mM thymidine for an additional 18 h) prior to fixation.

pHH3 Ser 10 (rabbit immunoglobulin (Ig) G, polyclonal) antibodies were purchased from Upstate (Billerica, California, USA), and pHH3 Ser 28 (rabbit IgG and Clone E191) were purchased from Epitomics (Burlingame, California, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

IHC was performed in accordance with Mosaic Laboratories’ validated protocols. Specimens were sectioned at 4 µ thickness, mounted onto positive-charged glass slides, dried, baked, deparaffinised and rehydrated. Following rehydration, tissue sections were incubated in Envision Peroxidase (Dako, Carpinteria, California, USA) for 5 min to quench endogenous peroxidase. Tissue sections then underwent pretreatment using High Tide Buffer (Mosaic Laboratories, Lake Forest, California, USA) for 40 min in a waterbath set to 95°C followed by a rinse in Splash-T Buffer (Mosaic Laboratories). Slides were incubated with Sniper (Biocare Medical, Concord, California, USA) for 5 min, which was then tapped off onto an absorbent pad. Slides were incubated with pHH3 (Ser28) antibody or pHH3 (Ser10) diluted in Dako Diluent (Dako) for 30 min. Slides were then rinsed in buffer for 5 min followed by detection using the Envision+Rabbit HRP detection reagent (Dako) for 30 min. Slides were rinsed with buffer for 5 min followed by incubation with DAB (Dako) for either 5 (Ser10) or 10 min (Ser28). Slides were rinsed with water, counterstained with Dako haematoxylin, blued in ammonia water, dehydrated through graded alcohols, cleared in xylene and coverslipped. Enumeration was performed by manual review of approximately 600–1000 cells per image, where possible.

Data analysis

Tests and descriptive statistics (means and SDs) were computed by tumour type. Because the data clearly were not normally distributed, with many low measurements and a few outlying high measurements, non-parametric tests were used for comparisons resulting in p values. For the analysis of the Part I data, Wilocoxon's Signed Rank Test was used to compare the pHH3 expression levels as measured by the two different approaches, tested within both tumour types. The Spearman correlation (correlation of the ranks) between Ser10 and Ser28 was calculated for the combined ovarian and melanoma samples. Wilcoxon's Rank Sum Test was used to compare pHH3 levels between tumour types in Part I. For Part II tests, the Kruskal–Wallis test, a non-parametric alternative to analysis of variance was used to compare the pHH3 levels between different types of cancers.

For variability assessment between two evaluators, a variance components analysis of log (% Ser10) and log (% Ser28) data was conducted. The mixed model included an intercept term, a fixed effect for reviewer, a random effect for the particular stained sample that was repeatedly measured and a random residual error term. The latter two terms allow us to decompose the overall variance as a sum of variance from sample to sample and variance due to repeated review of the sample.

Results

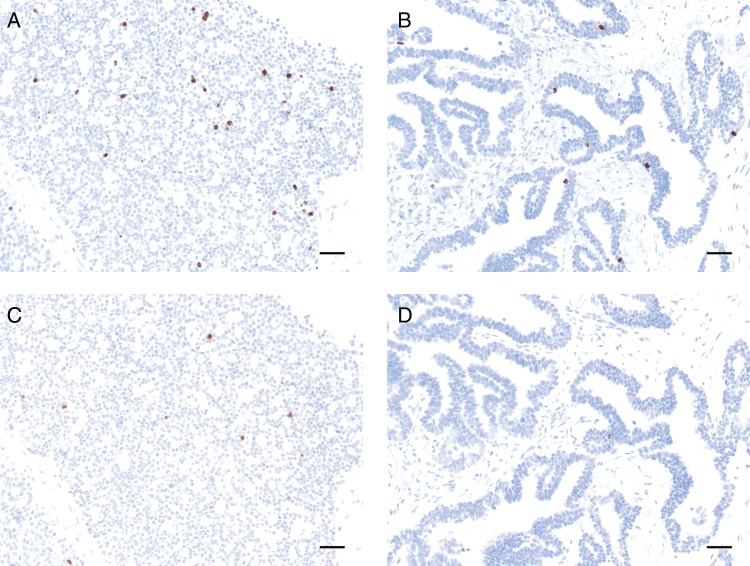

Demographic, clinical and pHH3 staining information on different types of cancer were summarised in table 1. IHC staining of two ovarian cancer samples is shown for each antibody in figure 1. In Part I melanoma samples, the percentage of cells that were pHH3 (Ser10) positive was statistically significantly higher than pHH3 (Ser28) (p=0.0039), with mean pHH3 of 1.28% (SD 0.47; range 0.73–2.13) for Ser10 and 0.53% (SD 0.44; range 0.14–1.69) for Ser28. In Part I ovarian cancer samples, mean pHH3 was also significantly higher for Ser10 than Ser28 (p=0.0020) with a mean of 3.47% (SD 3.51; range 0.60–11.70) for Ser10 and 0.62% (SD 0.68; range 0–2.30) for Ser28. The Spearman correlation of Ser10 with Ser28 (N=20, using both tumour types) was positive 0.30 but not statistically significant (p=0.1966), indicating that these two measures do not track each other within a sample in a robust fashion. Comparing pHH3 levels between ovarian and melanoma tumour samples, there was some evidence of a significant difference as measured by Ser10 (p=0.0638), but not Ser28 (p=1.000). On the basis of above results, Ser10 was selected as the antibody for assaying pHH3 in Part II.

Table 1.

The pHH3 expression levels among different types of cancers

| Tumour type | Sample size | Age (mean, SD) | Gender (male : female) | Prior therapy | Stage | Grade | pHH3 (Ser10) per cent positive* | pHH3 (Ser 28) per cent positive* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | 10 | 58.5 (14.1) | M=3 | Y=5 | II=1 | G1=0 | 1.28 (0.47) | 0.53 (0.44) |

| F=7 | N=4 | III=6 | G2=0 | 0.73–2.13 | 0.14–1.69 | |||

| U=1 | IV=1 | G3=0 | ||||||

| U=2 | U=10 | |||||||

| Ovarian | 10 | 61.7 (7.3) | M=0 | Y=1 | II=0 | G1=0 | 3.47 (3.51) | 0.62 (0.68) |

| F=10 | N=0 | III=4 | G2=1 | 0.60–11.70 | 0.00–2.30 | |||

| U=9 | IV=2 | G3=6 | ||||||

| U=4 | U=3 | |||||||

| Colorectal | 5 | 60.4 (13.5) | M=3 | Y=2 | II=1 | G1=0 | 3.73 (2.45) | |

| F=1 | N=0 | III=0 | G2=1 | |||||

| U=1 | U=3 | IV=4 | G3=0 | |||||

| U=0 | U=4 | |||||||

| Head/neck | 5 | 55.4 (9.8) | M=5 | Y=0 | II=0 | G1=0 | 3.00 (2.33) | |

| F=0 | N=3 | III=1 | G2=2 | |||||

| U=2 | IV=0 | G3=1 | ||||||

| U=4 | U=2 | |||||||

| Gastric | 5 | 61.6 (20.9) | M=4 | Y=2 | II=0 | G1=0 | 2.74 (1.62) | |

| F=1 | N=0 | III=2 | G2=2 | |||||

| U=3 | IV=3 | G3=3 | ||||||

| U=0 | U=0 | |||||||

| Oesophageal | 5 | 63.6 (11.4) | M=4 | Y=1 | II=1 | G1=1 | 2.36 (1.08) | |

| F=1 | N=2 | III=2 | G2=1 | |||||

| U=2 | IV=0 | G3=0 | ||||||

| U=2 | U=3 | |||||||

| Breast | 5 | 61.6 (20.6) | M=0 | Y=1 | II=0 | G1=0 | 1.80 (0.35) | |

| F=5 | N=0 | III=3 | G2=1 | |||||

| U=4 | IV=1 | G3=4 | ||||||

| U=1 | U=0 | |||||||

| NSCLC | 5 | 62.2 (8.2) | M=5 | Y=4 | II=0 | G1=0 | 1.42 (0.88) | |

| F=0 | N=1 | III=0 | G2=0 | |||||

| U=0 | IV=1 | G3=0 | ||||||

| U=3 | U=5 |

*Data are presented as mean (SD), and range.

NSCLC, non-small cell lung samples; pHH3, phosphorylated histone H3.

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs of ovarian cancer samples stained with the validated immunohistochemistry protocol for pHH3 (Ser10) or pHH3 (Ser28). Scale bar=50 μm. (a) Ser 10 ML0701077 Ovarian ×20. (b) Ser10 ML0705045A Ovarian ×20. (c) Ser 28 ML0701077 Ovarian ×20. (d) Ser 28 ML0705045A Ovarian ×20.

In Part II, mean pHH3 Ser10 expression was highest in colorectal cancer (3.73%, SD 2.45%), followed by head and neck cancer (3.00%, SD 2.33%), gastric cancer (2.74%, SD 1.62%), oesophageal cancer (2.36%, SD 1.08%), breast cancer (1.80%, SD 0.35%), NSCLC (1.42%, SD 0.88%). The differences in these six tumour types assessed in Part II were not found to be statistically significant at these limited group sizes via non-parametric testing (p=0.1969).

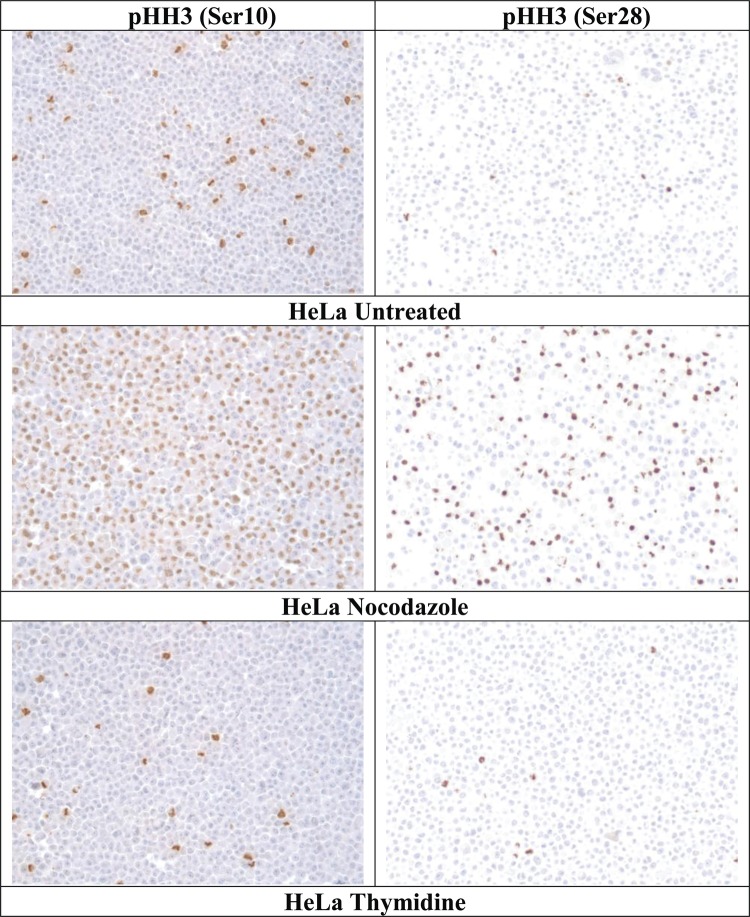

IHC staining results for the differentially cultured HeLa cells are listed in table 2 and images are presented in figure 2. Staining was less frequent with the pHH3 (Ser28) assay than the pHH3 (Ser10) in untreated (0.5% vs 4.75%) and nocodazole-treated (30.10% vs 51.16%) HeLa cells, although similar in thymidine-treated HeLa cells (1.78% vs 1.91%). In HeLa cells stained with both pHH3 IHC assays, the staining intensity of positive cells was similar between Ser10 and Ser28 pHH3 IHC assays.

Table 2.

pHH3 expression levels in differentially treated HeLa cells

| pHH3 | pHH3 | |

|---|---|---|

| Ser10, positive (%) | Ser28, positive (%) | |

| HeLa, untreated | 4.75 | 0.50 |

| HeLa, nocodazole | 51.16 | 30.10 |

| HeLa, thymidine | 1.91 | 1.78 |

pHH3, phosphorylated histone H3.

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs (×20) of the HeLa cell line stained with the validated immunohistochemistry protocol for pHH3 (Ser10) or pHH3 (Ser28).

Manual enumeration performed by two independent reviewers of the per cent positive staining observed in melanoma and ovarian cancer samples is summarised in table 3. The per cent positive staining was performed on approximately 1000 tumour cells per image, which was consistent for each reviewer.

Table 3.

Variance components for log per cent positive staining for pHH3 (Ser10) and pHH3 (Ser28) in human melanoma and ovarian cancer

| Tumor type | Assay type | Total variability | Sample to sample | Review to review | Total due to review (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | Ser10 | 0.1156 | 0.0567 | 0.0589 | 51.0 |

| Ser28 | 0.5444 | 0.4909 | 0.0535 | 9.8 | |

| Ovarian | Ser10 | 0.7362 | 0.7243 | 0.0119 | 1.6 |

| Ser28 | 0.8597 | 0.8144 | 0.0453 | 5.3 |

No significant difference was found between results generated by independent reviewers. Table 3 provides results for breakdown of the overall variance. With the exception of Ser10 in melanoma, results indicate that the variability from sample to sample is the dominant source of variation, and that multiple reviews of the same stained sample are a relatively minor component of the overall variability.

Discussion

Measurement of pHH3 levels can be used for quantifying mitosis and the effectiveness of mitotic inhibitors in early drug development. A number of previous studies have measured pHH3 levels among different types of cancers. Studies suggested that pHH3 index increased with higher grade of tumour, including cancers of breast, ovarian, melanoma, vulval intraepithelial neoplasia and meningioma, and limited studies suggested no difference between different grades of tumour for colorectal cancer or squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx.1–7 10 The strong correlation between pHH3 (Ser10) and mitotic index has been confirmed in multiple studies,1–3 and the detection of mitotic figures via pHH3 (Ser10) IHC analysis has been described as having superior sensitivity due to enhanced detection of prophase cells and better specificity due to lack of staining in apoptotic cells. The pHH3 levels have been shown to be a prognostic factor for different types of cancers. At the time this study was performed, there were no data comparing pHH3 levels between Ser10 and Ser28 and pHH3 levels across different types of cancers.

Using uniformed techniques, and assay platforms in a single laboratory, we assessed pHH3 (Ser 10 and Ser 28) expression levels. Our results suggested that these two antibodies do not correlate to each other within a sample in a robust fashion, and pHH3 values measured using Ser10 were significantly higher than those obtained via Ser28. The results were confirmed by a second, independent reviewer of the slides.

A greater fraction of cells stained for pHH3 (Ser10) than pHH3 (Ser28) in untreated (4.75% and 0.5%, respectively) and nocodazole-treated HeLa cells (51.16% and 30.10%, respectively), although results were similar in thymidine-treated cells. Nocodazole arrests cells in M phase, so the increase in staining frequency is consistent with expectations of specificity for mitotic cells. In HeLa cells stained with both pHH3 IHC assays, the staining intensity of positive cells was similar between Ser10 and Ser28 pHH3 IHC assays. There are at least four possibilities for the divergent results. The first is that the phosphorylation sites are differentially regulated, and that not all mitotic cells will demonstrate pHH3 at both sites. The second possibility is that Ser10 is phosphorylated earlier or for a more prolonged period during mitosis than Ser28. Third, the pHH3 (Ser28) has been described as sensitive to delays in time to fixation;12 however, samples used for this study were controlled for fixation. Finally, the differences may be simply due to intrinsic antibody characteristics such as affinity and/or specificity. To address whether the decreased proportion of cells stained by pHH3 (Ser28) was because of inadequate sensitivity, we attempted to increase the sensitivity in specimens with divergent staining results. Increasing the pHH3 (Ser28) primary antibody concentration did not result in an increase in positive cells prior to appearance of non-specific staining (data not shown). This result supports the observation that phosphorylation of Ser28 is present only in a fraction of cells with Ser10 phosphorylation.

In Part II, no significant difference was observed among different tumour types (p=0.1969 non-parametric testing), which may probably be due to the sample size (n=5 for each). In addition, we could not perform subgroup analysis and check the variation of pHH3 levels by different demographic, pathology and clinical characteristics. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm the preliminary findings.

In conclusion, mitotic counts performed by evaluating cells that are positive by IHC for pHH3 at Ser10 were much higher than at Ser28, and pHH3 (Ser10) should be used for evaluating the effectiveness of mitotic inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Ms Sheila Erespe and Ms Kim Della Penna of Merck for their valuable help in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: AS conceived, designed or planned the study; AS, LD and CK collected or assembled data and performed or supervised analyses. AS, WZ, JL, PS, LD and CK interpreted results. AS, WZ, JL and LD wrote sections of initial draft; AS, WZ, JL, PS, LD and CK provided substantive suggestions for revision or critically reviewed subsequent iterations of manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: AS, WZ, JL and PS are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. and may own stock/stock options at Merck. LMD and CAK are employees of and shareholders in Mosaic Laboratories, which received a fee for work done from Merck.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Bossard C, Jarry A, Colombeix C, et al. Phosphohistone H3 labelling for histoprognostic grading of breast adenocarcinomas and computer-assisted determination of mitotic index. J Clin Pathol 2006;59:706–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ribalta T, McCutcheon IE, Aldape KD, et al. The mitosis-specific antibody anti-phosphohistone-H3 (PHH3) facilitates rapid reliable grading of meningiomas according to WHO 2000 criteria. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:1532–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skaland I, Janssen EA, Gudlaugsson E, et al. Phosphohistone H3 expression has much stronger prognostic value than classical prognosticators in invasive lymph node-negative breast cancer patients less than 55 years of age. Mod Pathol 2007;20:1307–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skaland I, Janssen EA, Gudlaugsson E, et al. Validating the prognostic value of proliferation measured by phosphohistone H3 (PPH3) in invasive lymph node-negative breast cancer patients less than 71 years of age. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;114:39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott IS, Heath TM, Morris LS, et al. A novel immunohistochemical method for estimating cell cycle part distribution in ovarian serous neoplasms: implications for the histopathological assessment of paraffin-embedded specimens. Br J Cancer 2004;90:1583–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott IS, Morris LS, Bird K, et al. A novel immunohistochemical method to estimate cell-cycle part distribution in archival tissue: implications for the prediction of outcome in colorectal cancer. J Pathol 2003;201:187–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatrath P, Scott IS, Morris LS, et al. Immunohistochemical estimation of cell cycle part in laryngeal neoplasia. Br J Cancer 2006;95:314–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott IS, Morris LS, Rushbrook SM, et al. Immunohistochemical estimation of cell cycle entry and part distribution in astrocytomas: applications in diagnostic neuropathology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2005;31:455–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colman H, Giannini C, Huang L, et al. Assessment and prognostic significance of mitotic index using the mitosis marker phospho-histone H3 in low and intermediate-grade infiltrating astrocytomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:657–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YJ, Ketter R, Steudel WI, et al. Prognostic significance of the mitotic index using the mitosis marker anti-phosphohistone H3 in meningiomas. Am J Clin Pathol 2007;128:118–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapur P, Rakheja D, Balani JP, et al. Phosphorylated histone H3, Ki-67, p21, fatty acid synthase, and cleaved caspase-3 expression in benign and atypical granular cell tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2007;131:57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirata A, Inada K, Tsukamoto T, et al. Characterization of a monoclonal antibody, HTA28, recognizing a histone H3 phosphorylation site as a useful marker of M-Part cells. J Histochem Cytochem 2004;52:1503–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.