Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the association between methylation of transposable elements Alu and long-interspersed nuclear elements (LINE-1) and lung function.

Design

Cohort study.

Setting

Outpatient Veterans Administration facilities in greater Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Participants

Individuals from the Veterans Administration Normative Aging Study, a longitudinal study of aging in men, evaluated between 1999 and 2007. The majority (97%) were white.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary predictor was methylation, assessed using PCR-pyrosequencing after bisulphite treatment. Primary outcome was lung function as assessed by spirometry, performed according to American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines at the same visit as the blood draws.

Results

In multivariable models adjusted for age, height, body mass index (BMI), pack-years of smoking, current smoking and race, Alu hypomethylation was associated with lower forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) (β=28 ml per 1% change in Alu methylation, p=0.017) and showed a trend towards association with a lower forced vital capacity (FVC) (β=27 ml, p=0.06) and lower FEV1/FVC (β=0.3%, p=0.058). In multivariable models adjusted for age, height, BMI, pack-years of smoking, current smoking, per cent lymphocytes, race and baseline lung function, LINE-1 hypomethylation was associated with more rapid decline of FEV1 (β=6.9 ml/year per 1% change in LINE-1 methylation, p=0.005) and of FVC (β=9.6 ml/year, p=0.002).

Conclusions

In multiple regression analysis, Alu hypomethylation was associated with lower lung function, and LINE-1 hypomethylation was associated with more rapid lung function decline in a cohort of older and primarily white men from North America. Future studies should aim to replicate these findings and determine if Alu or LINE-1 hypomethylation may be due to specific and modifiable environmental exposures.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Genetics

Article summary.

Article focus

Association between methylation, an epigenetic marker, and lung function.

Key messages

Relative hypomethylation of transposable elements is associated with lower lung function and more rapid lung function decline in a cohort of older North American primarily white men.

Strengths and limitations of this study

First study to evaluate methylation of transposable elements in relation to lung function.

Difficult to interpret implications of methylation patterns in transposable elements.

Introduction

Lung function has both environmental and genetic determinants.1–5 Epigenetic variation, which may influence gene expression patterns without changing DNA sequence, may mediate the effects of environmental exposures on disease outcomes. DNA methylation, one type of epigenetic change, is the reversible addition of a methyl group to cytosine nucleotides. Methylation changes may or may not persist over time in the human genome, as epigenetic marks are highly plastic.

A large portion of methylation sites within the genome are found in repeat sequences and transposable elements, such as Alu and long-interspersed nuclear element (LINE-1) which are among the most common and best characterised repetitive elements.6–8 Alu is the most abundant of the short-interspersed nuclear elements (SINE) with over one million copies per genome.9 Alu elements compose approximately 11% of the mass of human genome and contain 30% of its methylation sites.7 10 LINE-1 elements are present at over half a million copies.9 11 Methylation of repetitive elements such as Alu and LINE-1 has been shown to correlate with total genomic methylation content.11 12 Hypomethylation in transposable elements is associated with higher genomic instability and alterations or deregulation of gene expression.13 14

Prior studies have found associations between methylation of Alu or LINE-1 elements and various diseases including multiple cancers,7 cardiovascular disease,15–17 and neurological disease,18 as well as with markers of inflammation19 and the inflammatory response.20 Studies on gene-specific methylation and non-neoplastic lung disease have found associations between GATA4, CDKN2A (p16) and lung function and an interaction with wood smoke exposure,21 as well as multiple genes in association with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) presence and severity.22 To our knowledge no prior study has investigated associations between methylation of transposable elements and non-neoplastic lung disease. Moreover, case–control studies which are common in genomic studies are more problematic for epigenetic marks since sampling cases after disease onset makes it impossible to determine whether epigenetic changes preceded or resulted from the disease. Hence, cohort studies or nested case−control studies within cohorts are particularly valuable. Our aim was to examine whether methylation of the repetitive elements Alu and LINE-1 was associated with measures of lung function, COPD status and longitudinal change in lung function in a cohort of men, the Normative Aging Study. Preliminary results from these analyses were previously reported in abstract form.23

Methods

Population

Study participants were from the Veterans Administration Normative Aging Study, an ongoing longitudinal study of aging established in 1963.24 This is a cohort of 2280 healthy male volunteers from the greater Boston, Massachusetts, area who were 21–80 years of age at entry and who enrolled after an initial health screening determined that they were free of known chronic medical conditions. Participants were re-evaluated every 3–5 years using detailed on-site physical examinations and questionnaires. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions. All participants gave written informed consent.

Prior to 1999, 706 individuals had died and others were either lost to follow-up, being followed by questionnaire only, or had no blood samples left for analyses (n=792). All 782 individuals had blood samples that were available for methylation analysis resulting in 704 with unique IDs and methylation data as previously described.25 26 For this study, individuals evaluated at least once between March 1999 and June 2007 with methylation data and concomitant spirometry were included. During the study period, this included 663 total individuals, 194 of whom reported for blood draw two times, for a total of 857 samples collected. For the analysis of lung function decline, a second spirometric measurement was available on 301 individuals who had had an initial blood draw for methylation measurement.

Measures

Spirometry was performed as previously described27 and was repeated up to a maximum of eight spirograms, so that at least three acceptable spirograms were obtained, at least 2 of which were reproducible with forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) measurements within 5% of each spirogram; the best of these 2 values was selected from a given encounter. Acceptability of spirograms was judged according to American Thoracic Society standards.28 29All spirometric values are pre-bronchodilator. Per cent predicted values for FEV1 and FVC were calculated using equations by Crapo et al30 COPD was defined as GOLD stage II or higher (FEV1/FVC<70% and FEV1<80% predicted).31 Techniques for assessing DNA methylation were previously described in detail.32 33 Briefly, we performed DNA methylation assessment of Alu and LINE-1 repetitive elements on bisulphite-treated blood leucocyte DNA using highly quantitative PCR–pyrosequencing technology. The degree of methylation was expressed as the percentage of methylated cytosines over the sum of methylated and unmethylated cytosines. Each marker was tested in triplicate, and their average was used in the statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

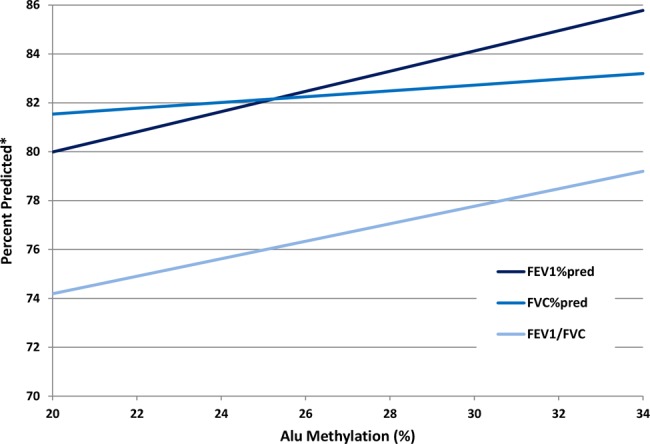

Analyses for cross-sectional associations were performed using repeated measures with adjustment for the correlation between measurements in a given individual using mixed effects models (PROC MIXED) for continuous outcomes (FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC) and generalised estimating equations (PROC GENMOD) for binary outcomes (COPD). Covariates in multivariable models were chosen for their clinical relevance and strong bivariate associations (p≤0.05) with lung function or change in effect estimate criterion of >10% after addition to the model and included age, height, race, pack-years of cigarette smoking, smoking status (dichotomised as current vs ex-smokers and never smokers) and body mass index (BMI). We also considered variables previously associated with methylation of repetitive elements,34 such as folate intake, alcohol intake, total white blood cell count and both per cent neutrophils and per cent lymphocytes. With the exception of per cent lymphocytes, which was included in models with LINE-1 only, these covariates were not included in final models because they were not associated with Alu or LINE-1 methylation and did not meet the change in estimate criteria. Because figure 2 depicts bivariate relationships, per cent predicted values were used for both FEV1 and FVC to show an adjusted value; actual values for FEV1 and FVC were utilised in multivariable models. To examine associations between methylation of Alu and LINE-1 and change in lung function over time, a rate was calculated using the change in lung function between the two time points divided by the amount of time elapsed between the two measurements in years. This value was utilised as an outcome and analysed using multivariate linear regression models. A total of 301 individuals had a second lung function data point subsequent to the initial methylation value. SAS V.9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) was used for all analyses.

Figure 2.

Alu methylation and lung function bivariate associations between Alu methylation and forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)% predicted, forced vital capacity (FVC)% predicted and FEV1/FVC. *For FEV1/FVC y axis is per cent, not per cent predicted.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the 663 individuals included in this study as well as of the subset of 301 individuals with two lung function measures are shown in table 1. All were male and the majority (640, 97%) of white race. Forty-three (7%) were current smokers and 197 (30%) were never smokers. There was wide variation in lung function values. Of the 107 individuals with COPD, 77 (72%) were GOLD stage II, 26 were stage III and 4 were stage IV; overall 20 (20%) of the individuals with COPD were current smokers.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 663 individuals from the Normative Aging Study and subset of 301 individuals who had more than one lung function measurement for analysis of lung function decline

| Full data set | 301 Subset | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or N (%) | Range | Mean (SD) or N (%) | Range | |

| Age | 72.7 (6.7) | (55.3–100.9) | 71.5 (6.4) | (55.3–91.0) |

| BMI | 28.5 (4.2) | (19.4–52.3) | 28.7 (4.1) | (20.3–52.3) |

| Pack-years* | 30.6 (24.8) | (0.1–145.5) | 28.6 (23.1) | (0.10–120.8) |

| Current smokers | 43 (7) | 23 (8) | ||

| Ever smokers | 466 (70) | 216 (70) | ||

| Folate intake† (mcg/day) | 570 (333) | (0.23–2235.17) | 617 (383) | (0.23–2001.75) |

| Alcohol intake (gm/day) | 12.0 (17.8) | (0–217.8) | 10.7 (13.8) | (0–73.5) |

| WBC (×103/mm3) | 6.7 (1.8) | (2.7–23.8) | 6.6 (2.3) | (3.2–36.6) |

| Per cent lymphocytes | 25.6 (8.0) | (5–88) | 25.0 (8.3) | (7–85) |

| Per cent neutrophils | 62.1 (8.7) | (5–85) | 62.8 (8.8) | (5–83) |

| Cardiovascular disease‡ | 115 (17) | 49 (16) | ||

| Hypertension | 280 (42) | 143 (47) | ||

| Diabetes | 75 (11) | 33 (11) | ||

| FEV1 | 2.70 (0.64) | (0.85–4.69) | 2.76 (0.62) | (1.29–4.69) |

| FEV1% predicted | 81 (17) | (28–125) | 81.8 (15.5) | (39.7–122.6) |

| FVC | 3.56 (0.72) | (1.63–6.32) | 3.64 (0.71) | (1.63–6.32) |

| FVC% predicted | 82 (14) | (43–124) | 82.6 (13.1) | (43.8–123.8) |

| FEV1/FVC | 75 (8) | (36–94) | 75.6 (7.0) | (51.6–94.4) |

| COPD | 107 (16) | 45 (15) | ||

| Alu | 26.4 (1.1) | (22.8–32.4) | 26.4 (1.10) | (22.8–32.3) |

| LINE-1 | 76.8 (1.8) | (70.1–84.6) | 77.0 (1.8) | (70.1–81.6) |

*Pack-years in current or ex-smokers only.

†Calculated based on supplement intake and fortified foods from food frequency questionnaire.

‡Angina, stroke, myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease.

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; LINE-1, long-interspersed nuclear elements; WBC, white blood cell count.

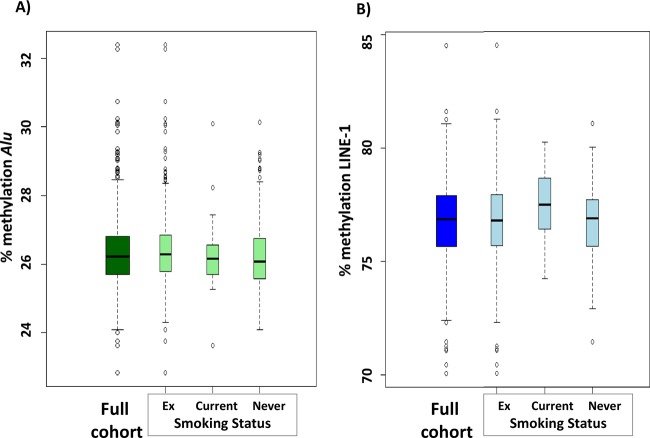

The distribution of percentage methylation of both Alu and LINE-1 elements among the population and stratified by smoking status is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution (median, IQR) of percentage (A) Alu and (B) long-interspersed nuclear elements (LINE-1) methylation in the overall cohort and stratified by smoking status.

Bivariate relationships between Alu and LINE-1 methylation with outcomes and covariates considered for inclusion in the multivariable model are shown in table 2. Alu methylation was associated or showed a trend towards association positively with FEV1, BMI and FEV1/FVC and negatively with age and COPD status. LINE-1 methylation was positively associated with current smoking and negatively with per cent lymphocytes. Neither Alu nor LINE-1 methylation was associated with FVC, pack-years of smoking or ever smoking status. Folate intake, alcohol intake, total white blood cell count and per cent neutrophils were not significantly associated with Alu or LINE-1 methylation in bivariate analyses. There was no significant relationship between methylation of Alu and LINE-1 to each other (p=0.23).

Table 2.

Bivariate associations between Alu, LINE-1 methylation and other covariates

| Alu | LINE-1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p Value | β | p Value | |

| Age | −0.3 | 0.07 | −0.2 | 0.1 |

| BMI | 0.106 | 0.059 | 0.054 | 0.17 |

| Current smoking | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.697 | 0.0002 |

| Per cent lymphocytes | 0.08 | 0.73 | −0.31 | 0.04 |

| FEV1 | 0.024 | 0.06 | −0.006 | 0.53 |

| FVC | 0.023 | 0.22 | −0.004 | 0.73 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.31 | 0.046 | −0.05 | 0.67 |

| COPD | OR 0.87 (0.73 to 1.03) | 0.1 | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.13) | 0.76 |

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; LINE-1, long-interspersed nuclear elements.

In multivariate models that included age, height, race, pack-years of smoking, smoking status and BMI, Alu methylation was positively associated with FEV1, and showed a trend towards association with FVC and FEV1/FVC. Because of recent data suggesting that current smoking status may have differential effects on methylation,35 36 and because this may relate to disease outcome or risk, we investigated whether our results would change if current smokers were excluded from the analyses. Higher Alu methylation was still associated with lower odds of COPD (OR 0.80 (0.64 to 0.99) p=0.046). In analyses of lung function measures, results were in the same direction but were no longer significant except for FEV1/FVC (FEV1 p=0.17, FVC p=0.7, FEV1/FVC p=0.029). There were no significant associations between LINE-1 methylation and any of the cross-sectional outcomes (table 3). Figure 2 depicts the bivariate associations of Alu methylation with FEV1% predicted, FVC% predicted and FEV1/FVC.

Table 3.

Multivariate models for lung function and both Alu and LINE-1 methylation*

| Alu | LINE-1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p Value | Β | p Value | |

| FEV1 | 0.028 | 0.017 | −0.015 | 0.08 |

| FVC | 0.027 | 0.06 | −0.017 | 0.11 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.3 | 0.057 | −0.092 | 0.44 |

| COPD | 0.85 (0.71 to 1.03) | 0.09 | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.15) | 0.83 |

*Adjusted for age, height, race, BMI, pack-years of smoking, smoking status. Models with LINE-1 also include per cent lymphocytes.

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; LINE-1, long-interspersed nuclear elements.

We also analysed whether methylation of Alu and LINE-1 were associated with rate of change in lung function in a subset of participants who had two consecutive lung function measures (N=301). The mean number of years elapsed between measurements was 4.03 (SD 1.23). Models were adjusted for baseline FEV1, FVC or FEV1/FVC (respectively for the given outcome) as well as age, pack-years of smoking, BMI, height, race, per cent lymphocytes and smoking status. Relative hypomethylation in LINE-1 but not Alu was associated with faster rate of decline in FEV1 and FVC (p<0.005). Neither measure was associated with rate of change of FEV1/FVC (table 4). Including both Alu and LINE-1 methylation in the models did not change the results (data not shown). Because of prior associations between methylation of repetitive elements and cardiovascular disease,15–17 we repeated both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses including variables for cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, stroke, angina, hypertension, ischaemic heart disease) and diabetes and found no difference in the results (data not shown). Analyses were also repeated in whites only to determine whether results might be due to population stratification and results did not change (data not shown). Analyses excluding current smokers remained significant (data not shown). Because of the known association between aging and methylation, we also repeated the models using age2, as an additional covariate to saturate the model for an age effect and found no difference in our results (data not shown).

Table 4.

Multivariate models for rate of change in lung function (in l/year) and both Alu and LINE-1 methylation*

| Alu | LINE-1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p Value | β | p Value | |

| FEV1 rate | −0.0028 | 0.49 | −0.0069 | 0.005 |

| FVC rate | −0.00098 | 0.84 | −0.0096 | 0.0021 |

| ratio rate | −0.00079 | 0.17 | 0.00005 | 0.89 |

*Adjusted for age, height, race, BMI, pack-years of smoking, smoking status and baseline FEV1, FVC or FEV1/FVC respectively depending on outcome. Models with LINE-1 also adjusted for per cent lymphocytes.

BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; LINE-1, long-interspersed nuclear elements.

Discussion

We examined associations between methylation levels of the repetitive elements Alu and LINE-1 in a cohort of older men in relation to lung function and COPD status. In cross-sectional analyses, we found that Alu hypomethylation was associated with lower FEV1 with a trend towards association with lower FVC and FEV1/FVC. LINE-1 hypomethylation was associated with more rapid lung function decline (FEV1 and FVC).

Prior studies have found associations between methylation of repetitive transposable elements such as Alu and LINE-1 and several diseases including multiple cancers,7 cardiovascular disease15–17 and neurological disease,18 as well as with markers of inflammation.19 To our knowledge this is the first study to examine associations between methylation of Alu and LINE-1 transposable elements and measures of lung function.

Previous work has shown that in normal subjects, Alu hypomethylation is associated with increased age,8 37 greater alcohol use and gender (lower in males).34 In this same cohort (Normative Aging Study), hypomethylation has been associated with higher incidence of cancer in general and lung cancer specifically (LINE-1 methylation), as well as higher mortality from cancer (Alu and LINE-1 methylation).38 A variety of environmental exposures such as lead,39 traffic particles,33 organic pollutants,40 metals, air pollutants and endocrine disrupting agents,41 may all affect global methylation levels, specifically some that may relate to lung function such as various air pollutants.

Hypomethylation of transposable elements may or may not be causally linked to lower lung function and faster rates of lung function decline. Lower methylation of Alu and LINE-1 may increase their activity as retrotransposable sequences, leading to greater genomic instability and more mutations.13 Furthermore, oxidative damage caused by environmental exposures may cause hypomethylation.42 This may lead to alteration of gene expression through a variety of mechanisms including disrupting transcription factor binding sites or reading frames, altering regulatory sequences, altering methylation patterns of gene promoters or introducing new transcription factor-binding sites.43–45 Alu elements specifically are preferentially found in gene-rich regions.46 Black carbon and increased PM2.5 exposure,33 as well as PM10 exposure,41 have been found to be inversely associated with LINE-1 methylation and both Alu and LINE-1 methylation, respectively, which may impact on lung function or lung function decline.47 LINE-1 hypomethylation may also increase transcription of genes that have LINE-1 in regulatory regions. It is possible that other specific environmental or dietary exposures previously not known to be associated with lung function may be mediated through epigenetic changes such as Alu or LINE-1 hypomethylation. Alternatively, this may be a marker of a specific exposure but not causally linked to lower lung function. Lastly, because Alu methylation decreases with increasing age, as does lung function, our findings may represent some other measure of ‘aging’ or exposures resulting in similar processes beyond just chronological age.8 We repeated all of our analyses using age2, as an additional covariate to saturate for an age effect and found no differences in our results. As our understanding of epigenetic processes and the exposures that affect these processes increases, the implications of our findings will become clearer.

These data must be interpreted in the context of the study design. Our study was limited to older men the majority of whom were white, and our findings may or may not be generalisable to other populations. It is difficult to know how to interpret methylation of retrotransposons, as opposed to gene-specific methylation, in relation to specific outcomes such as lung function and lung function decline. Future studies in this and other cohorts should include gene-specific methylation analyses similar to Qiu et al,22 to elucidate mechanisms by which methylation changes may relate to these outcomes. We did not control for a variety of environmental exposures that may be associated with both lung function and methylation. However, alteration in methylation patterns may be the pathway through which these changes are mediated and thus including these exposures in multivariate models would be overadjusting. Methylation levels vary in different tissue types and it is possible that assessments of methylation in white blood cells may not reflect alterations seen in lung tissue. However, systemic processes involving white blood cells, such as inflammation, may play a role in the pathophysiology of lung function decline,48 and may nonetheless be markers of specific exposures (such as cigarette smoking) that exert a systemic effect.

In summary, we found that relative hypomethylation of Alu was associated with lower lung function measures, and that LINE-1 hypomethylation was associated with more rapid lung function decline. Future studies on both gene-specific methylation as well as exposures related to methylation of retrotransposons will improve our understanding of the relationship between epigenetic changes and lung function, potentially informing new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to lung function decline and diseases such as COPD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the participants of the Normative Aging Study.

Footnotes

Contributors: NEL designed the study, performed the data analysis and prepared the manuscript. JS contributed to the data analysis and provided critical revision of the manuscript. LT contributed to data collection and provided critical revision of the manuscript. VB contributed to data collection and provided critical revision of the manuscript. DS and PV were involved in conception of the study and critical revision of the manuscript. AZ contributed to data collection and provided critical revision of the manuscript. JS contributed to the study design and provided critical revision of the manuscript. AB contributed to data collection and provided critical revision of the manuscript. AAL contributed to study design, assisted with the data analysis and provided critical revision of the manuscript. DLD designed the study, assisted with the data analysis, and provided critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: Funded by NIH grants AG027214, ES015172, ES014663, HL007427, HL089438, ES015172–01 and ES000002, and VA Research and Development Service. DM is supported by a Doris Duke Clinical Scientist Development Award. The Cooperative Studies Program/Epidemiology Research and Information Center of the US Department of Veterans Affairs supported the VA Normative Aging Study, which is a component of the Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center, Boston, MA. This research was also supported by a VA Research Career Scientist award to D S.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics Approval : Veterans administration.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Hancock DB, Eijgelsheim M, Wilk JB, et al. Meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies identify multiple loci associated with pulmonary function. Nat Genet 2011;42:45–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hubert HB, Fabsitz RR, Feinleib M, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on pulmonary function in adult twins. Am Rev Respir Dis 1982;125:409–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClearn GE, Svartengren M, Pedersen NL, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on pulmonary function in aging Swedish twins. J Gerontol 1994;49:264–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redline S, Tishler PV, Rosner B, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic similarities in pulmonary function among family members of adult monozygotic and dizygotic twins. Am J Epidemiol 1989;129:827–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soler Artigas M, Loth DW, Wain LV, et al. Genome-wide association and large-scale follow up identifies 16 new loci influencing lung function. Nat Genet 2011;43:1082–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehrlich M, Gama-Sosa MA, Huang LH, et al. Amount and distribution of 5-methylcytosine in human DNA from different types of tissues of cells. Nucleic Acids Res 1982;10:2709–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson AS, Power BE, Molloy PL. DNA hypomethylation and human diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007;1775:138–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bollati V, Schwartz J, Wright R, et al. Decline in genomic DNA methylation through aging in a cohort of elderly subjects. Mech Ageing Dev 2009;130:234–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 2001;409:860–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deininger PL, Batzer MA. Alu repeats and human disease. Mol Genet Metab 1999;67:183–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang AS, Estecio MR, Doshi K, et al. A simple method for estimating global DNA methylation using bisulfite PCR of repetitive DNA elements. Nucleic Acids Res 2004;32:e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisenberger DJ, Campan M, Long TI, et al. Analysis of repetitive element DNA methylation by MethyLight. Nucleic Acids Res 2005;33:6823–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gravina S, Vijg J. Epigenetic factors in aging and longevity. Pflugers Arch 2010;459:247–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dean W, Lucifero D, Santos F. DNA methylation in mammalian development and disease. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 2005;75:98–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baccarelli A, Wright R, Bollati V, et al. Ischemic heart disease and stroke in relation to blood DNA methylation. Epidemiology 2010;21:819–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castro R, Rivera I, Struys EA, et al. Increased homocysteine and S-adenosylhomocysteine concentrations and DNA hypomethylation in vascular disease. Clin Chem 2003;49:1292–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim M, Long TI, Arakawa K, et al. DNA methylation as a biomarker for cardiovascular disease risk. PLoS One 2010;5:e9692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bollati V, Galimberti D, Pergoli L, et al. DNA methylation in repetitive elements and Alzheimer disease. Brain Behav Immun 2011;25:1078–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baccarelli A, Tarantini L, Wright RO, et al. Repetitive element DNA methylation and circulating endothelial and inflammation markers in the VA normative aging study. Epigenetics 2010;5:222–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crow MK. Long interspersed nuclear elements (LINE-1): potential triggers of systemic autoimmune disease. Autoimmunity 2010;43:7–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sood A, Petersen H, Blanchette CM, et al. Wood smoke exposure and gene promoter methylation are associated with increased risk for COPD in smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:1098–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiu W, Baccarelli A, Carey VJ, et al. Variable DNA methylation is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:373–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lange NE, Sordillo JE, Tarantini L, et al. Global DNA methylation and lung function in the normative aging study (abstract). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:A5694 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bell B, Rose C, Damon A. The Normative aging study: an interdisciplinary and longitudinal study of health and aging. Aging Human Dev 1972;3:5–17 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madrigano J, Baccarelli A, Mittleman MA, et al. Prolonged exposure to particulate pollution, genes associated with glutathione pathways, and DNA methylation in a cohort of older men. Environ Health Perspect 2011;119:977–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright RO, Schwartz J, Wright RJ, et al. Biomarkers of lead exposure and DNA methylation within retrotransposons. Environ Health Perspect 2010;118:790–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sparrow D, O'Connor G, Colton T, et al. The relationship of nonspecific bronchial responsiveness to the occurrence of respiratory symptoms and decreased levels of pulmonary function. The Normative Aging Study. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987;135:1255–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Standardization of spirometry—1987 update Statement of the American Thoracic Society. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987;136:1285–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152:1107–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crapo RO, Morris AH, Gardner RM. Reference spirometric values using techniques and equipment that meet ATS recommendations. Am Rev Respir Dis 1981;123:659–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Updated 2010) http://www.goldcopd.org/Guidelineitem.asp?l1=2&l2=1&intId=989 (accessed 17 May 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bollati V, Baccarelli A, Hou L, et al. Changes in DNA methylation patterns in subjects exposed to low-dose benzene. Cancer Res 2007;67:876–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baccarelli A, Wright RO, Bollati V, et al. Rapid DNA methylation changes after exposure to traffic particles. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:572–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu ZZ, Hou L, Bollati V, et al. Predictors of global methylation levels in blood DNA of healthy subjects: a combined analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:126–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breitling LP, Yang R, Korn B, et al. Tobacco-smoking-related differential DNA methylation: 27K discovery and replication. Am J Hum Genet 2011;88:450–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wan ES, Qiu W, Baccarelli A, et al. Cigarette smoking behaviors and time since quitting are associated with differential DNA methylation across the human genome. Hum Mol Genet 2012;21:3073–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jintaridth P, Mutirangura A. Distinctive patterns of age-dependent hypomethylation in interspersed repetitive sequences. Physiol Genomics 2010;41:194–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu ZZ, Sparrow D, Hou L, et al. Repetitive element hypomethylation in blood leukocyte DNA and cancer incidence, prevalence, and mortality in elderly individuals: the Normative Aging Study. Cancer Causes Control 2010;22:437–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pilsner JR, Hu H, Ettinger A, et al. Influence of prenatal lead exposure on genomic methylation of cord blood DNA. Environ Health Perspect 2009;117:1466–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rusiecki JA, Baccarelli A, Bollati V, et al. Global DNA hypomethylation is associated with high serum-persistent organic pollutants in Greenlandic Inuit. Environ Health Perspect 2008;116:1547–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baccarelli A, Bollati V. Epigenetics and environmental chemicals. Curr Opin Pediatr 2009;21:243–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valinluck V, Tsai HH, Rogstad DK, et al. Oxidative damage to methyl-CpG sequences inhibits the binding of the methyl-CpG binding domain (MBD) of methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2). Nucleic Acids Res 2004;32:4100–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norris J, Fan D, Aleman C, et al. Identification of a new subclass of Alu DNA repeats which can function as estrogen receptor-dependent transcriptional enhancers. J Biol Chem 1995;270:22777–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vansant G, Reynolds WF. The consensus sequence of a major Alu subfamily contains a functional retinoic acid response element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995;92:8229–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asada K, Kotake Y, Asada R, et al. LINE-1 hypomethylation in a choline-deficiency-induced liver cancer in rats: dependence on feeding period. J Biomed Biotechnol 2006;2006:17142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Batzer MA, Deininger PL. Alu repeats and human genomic diversity. Nat Rev Genet 2002;3:370–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andersen ZJ, Hvidberg M, Jensen SS, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution: a cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;183:455–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nussbaumer-Ochsner Y, Rabe KF. Systemic manifestations of COPD. Chest 2011;139:165–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.