Abstract

Background

While implications of myocardial fibrosis on left ventricular (LV) function at rest have been studied in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), the pathophysiological consequences on dynamic LV outflow tract (LVOT) gradient have so far not been investigated in detail.

Objective

To evaluate the influence of myocardial fibrosis, detected by MRI as late-gadolinium enhancement (LGE), on LVOT gradient in HCM.

Design

Retrospective database analysis.

Setting

A single Italian cardiomyopathies referral centre.

Patients

Seventy-six HCM patients with normal ejection fraction at rest.

Interventions

Patients underwent cardiac MR and performed bicycle exercise echocardiogram within a month.

Results

LGE was present in 54 patients (71%), ranging from 0.2% to 32.4% of LV mass. There was a weak correlation between the amount of fibrosis and LVOT gradient variation during exercise in the overall population (r=−0.243, p=0.034) and a stronger correlation in patients with obstructive HCM at rest (r=−0.524, p=0.021). Patients with an LVOT gradient increase ≥50 mm Hg during exercise had a significantly lesser extent of fibrosis than those with an increase <50 mm Hg (0.7% (IQR 0–2.4) vs 3.2% (IQR 0.2–7.4), p=0.006). The extent of fibrosis was significantly lower among the highest quartiles of LVOT gradient increase (p=0.009).

Conclusions

In patients with HCM and normal ejection fraction at rest, myocardial fibrosis was associated with a lower increase in LVOT gradient during exercise, probably due to a lesser degree of myocardial contractility recruitment. This negative association was more evident in patients with an obstructive form at rest.

Article summary.

Article focus

Exploring influence of myocardial fibrosis (detected as late-gadolinium enhancement on cardiac MRI) on left ventricular outflow gradient during exercise in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Key messages

Myocardial fibrosis was associated with a lower increase in left ventricular outflow gradient during exercise. This negative association was more evident in patients with an obstructive form at rest.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is a first, small, hypothesis-generating study.

Lack of direct haemodynamic measurements.

Background

The pathophysiology of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the result of a number of interrelated factors that include impaired ventricular relaxation, increased myocardial stiffness, myocardial ischaemia, left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction and mitral regurgitation.1 2 In recent years MRI and exercise echocardiography have opened new possibilities for non-invasive evaluation of myocardial substrate and LV function in HCM.3–8 In particular, gadolinium-enhanced MRI has shown that a high percentage of patients with HCM has variable degrees of late-gadolinium enhancement (LGE) which, in this disease, has been shown to correspond to interstitial fibrosis.6–9 Myocardial fibrosis in HCM has been shown to be associated with an increased incidence of sudden death risk factors—particularly ventricular arrhythmias—9–11 and an increased risk of HCM-related morbidity and mortality.12–14 Additionally, myocardial fibrosis influences LV function at rest negatively.15 16 Not only are large confluent areas of LGE associated with the end-stage phase of the disease, but also lesser amounts of fibrosis seem to determine a reduction in LV systolic function at rest (albeit within the ‘normal’ ejection fraction (EF) range).15 The relationship between myocardial fibrosis and LV function during exercise remains unexplored. Since LVOT gradient during exercise is mainly related to the increase in LV contractility, we designed a hypothesis generating study to explore the relationship between MRI-assessed myocardial fibrosis and LV outflow gradient during exercise echocardiography in HCM patients with normal LV EF.

Methods

Patients

Ninety-one consecutive outpatients, evaluated at the S. Orsola-Malpighi University Hospital Bologna, Italy between January 2009 and November 2010, were considered for the study. Fifteen patients were excluded due to coexistent coronary artery disease (n=4), atrial fibrillation (n=3), previous surgical septal myectomy (n=1), LV EF <50% at rest (n=2) and general contraindications/refusal to MRI (n=5). All patients underwent contrast-enhanced cardiac MRI and bicycle exercise echocardiogram within a 1-month period. All patients fulfilled conventional criteria for HCM with LV hypertrophy ≥15 mm.17

All patients provided written informed consent for exercise echocardiography and MR. No specific ethical approval was required for this study that included only non-invasive examinations that HCM patients routinely undergo at our institution.

Exercise echocardiography protocol

Having suspended β-blockers and/or calcium antagonist and disopiramide for at least five half-lives, patients performed a symptom-limited bicycle exercise stress test in semisupine position on an exercise echo-tilting table (stress echo supine ergometer, Ergoselect 1200 EL, Ergoline GmbH, Bitz, Germany). The workload was increased by 25 W every 2 min. Blood pressure and 12-lead ECG were recorded every minute. Echocardiographic images were assessed at baseline and at peak exercise using a Philips Sonos 5500 Ultrasound System (Philips Ultrasound, Andover, Massachusetts, USA) equipped with a harmonic fusion imaging probe (s3) and off-line cineloop analysis software. All images were recorded digitally and analysed off-line and each parameter was measured on an average of three consecutive beats both at rest and during exercise. LV volumes and EF were calculated using the Simpson method from the apical four-chamber and two-chamber view. LV volumes were normalised to the body surface area. Mitral regurgitation was quantified with the colour-area method. Continuous wave Doppler was used to measure LV outflow gradient from the apical four-chamber view. The early filling (E) and late filling (A) velocities, as well as the deceleration time of early filling, were measured from the transmitral flow. Tissue Doppler velocities were recorded from the medial (septal) and lateral mitral annulus as previously reported18 and averaged; the ratio of early mitral diastolic inflow velocity to early diastolic mitral annular velocity (E/E′) was calculated.

MRI technique

MRI was performed on a 1.5 T scanner (Signa Twin Speed Excite, General Electric, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) with surface coils and prospective ECG triggering. LV end-systolic and end-diastolic diameters as well as maximal (end-diastolic) wall thickness were traced and recorded from the short-axis and long-axis views (8 mm slice thickness, no gap) of the standard ECG-gated steady state-free precession cine sequence. Image parameters were: repetition time 3.5 ms, echo time 1.6 ms, temporal resolution 40 ms, matrix 224×160, flip angle 45°, bandwidth 125 kHz, views per segment 8–16. LV volumes, mass and EF were measured from a stack of sequential 8 mm short axis slices (no gap) from the atrio-ventricular ring to the apex, through analysis with a commercially available software (Mass Analysis Plus, Medis, Leiden, the Netherlands) and were indexed to body surface in m². LGE images for detection of delayed hyperenhancement were acquired 10–15 min after intravenous administration of Gadopentate dimeglumine (0.2 mmol/kg) (Magnevist; Schering, Berlin, Germany) using a breath-hold segmented inversion recovery fast gradient echo sequence in the short-axis and in long-axis planes of the LV, with 9 mm slice thickness and no gap. Image parameters were: repetition time of 5.3 ms, echo time 1.3 ms, flip angle 20°, matrix 256×160, NEX 2 and field of view 320 mm. Optimal inversion time to null normal myocardial signal was determined for each patient and ranged from 220 to 320 ms. After visual inspection of all short-axis LV slices to identify areas of completely nulled myocardium (normal myocardium), the mean signal intensity of normal myocardial tissue was calculated and a threshold ≥2 SDs exceeding the mean was used to identify LGE areas. This limit was deemed acceptable to discriminate LGE from healthy myocardium without reducing sensibility. LGE areas were outlined manually and the total volume (expressed in grams) was quantified using specific software (ReportCard, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) and expressed as a percentage of LV mass. LGE analysis was performed by one experienced reader (LL, >8 years of MRI experience) and reviewed by a second reader (RF, >10 years of MRI experience).

Study design and statistical analysis

In order to explore a possible relation between myocardial fibrosis and LV outflow obstruction during exercise the following analyses were planned:

Linear regression analysis between the extent of fibrosis and maximum LVOT gradient during exercise.

Linear regression analysis between the extent of fibrosis and changes in LVOT gradient during exercise (in the overall population and in the patients with an obstructive form at rest, defined as LV gradient ≥30 mm Hg).

Comparison of fibrosis extent between patients with maximum gradient ≥ or <50 mm Hg, and between patients with an increase in exercise gradient ≥ or <50 mm Hg.

Comparison of fibrosis extent between patients with a gradient increase above or below the median value in our population, and among different quartiles of gradient increase.

Categorical variables are expressed as total numbers and percentages. Continuous variables are expressed as median values (IQR). Comparison of categorical variables was performed with the χ2 test and continuous variables were analysed with the Mann–Whitney U test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate. A p value of 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Regarding echocardiographic measurements, intraobserver variability was assessed in two different blind evaluations 30 days apart, whereas interobserver variability was assessed by two different observers (GR and EB). Both assessments were made on 15 patients’ sample. Data processing and statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS V.15.0 statistical program (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

LGE was present in 54 patients (71%), involving a percentage of LV mass ranging from 0.2% to 32.4%. Fibrosis consisted of small, diffuse areas in 32 patients (59%) and was confluent into a smaller number of larger areas in 22 patients (41%). Table 1 reports the clinical, resting echocardiographic and MRI characteristics of the study population. Regarding echocardiographic measurements, mean intraobserver variability for end-diastolic and for end-systolic volume were 4±1 ml/m² and 3±1 ml/m², respectively. Mean interobserver variability for end-diastolic and for end-systolic volume were 5±1 and 4±1 ml/m², respectively. Mean intraobserver and interobserver variability of Doppler indexes of LV filling were as follows: E wave 0.08±2.36 and 1.20±4.30 cm/s; A wave 0.12±1.96 and 0.64±4.54 cm/s.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical, echocardiographic and MR characteristics

| Clinical | |

|---|---|

| Number of patients, n (%) | 76 |

| Males, n (%) | 51 (67) |

| Age (years) | 48 (41–61) |

| Family history of HCM, n (%) | 34 (45) |

| Family history of SD, n (%) | 10 (13) |

| NYHA functional class I, n (%) | 61 (80) |

| NYHA functional class II, n (%) | 14 (18) |

| Unexplained syncope, n (%) | 12 (16) |

| NSVT on Holter monitor, n (%) | 21 (28) |

| Echocardiography | |

| LV gradient ≥30 mm Hg at rest, n (%) | 20 (26) |

| Maximum WT (mm) | 20 (17–23) |

| Maximum WT ≥30 mm, n (%) | 3 (4) |

| Left atrium diameter (mm) | 43 (39–48) |

| MRI | |

| LV mass (g/m²) | 155 (124–196) |

| LV mass/end-diastolic volume (g/ml) | 1.09 (0.92–1.46) |

| LGE % of LV mass (%) | 2.4 (0–6) |

Continuous variables are expressed as median values (IQR).

HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LV, left ventricle; NSVT, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SD, sudden death; WT, wall thickness.

The variation of echocardiographic characteristics from rest to exercise is reported in table 2. HCM patients performed a maximum workload of 100 W (IQR 75–125) with a median heart rate increase from 73 (IQR 66–84) to 128 (IQR 112–142) bpm. Median LV outflow gradient increased from 11 (IQR 7–31) to 27 (IQR 16–98) mm Hg on exercise; 15 patients (20%) without obstruction at rest developed a gradient ≥30 mm Hg on exercise and 18 (24%) had an increase in outflow gradient ≥50 mm Hg. In 28 patients (37%) EF did not increase or decreased with exercise.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic data at rest and during exercise

| Rest | Exercise | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum workload (W) | 100 (75, 125) | ||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 73 (66, 84) | 128 (112, 142) | <0.001 |

| Left ventricle outflow gradient (mm Hg) | 11 (7, 31) | 27 (16, 98) | <0.001 |

| Δ Left ventricle outflow gradient (mm Hg) | 14 (8, 46) | ||

| Mitral regurgitation jet area (cm²) | 1.2 (0.1, 3.1) | 3.0 (0.6, 7.1) | <0.001 |

| Δ Mitral regurgitation jet area (cm²) | 0.6 (0, 3.6) | ||

| End-diastolic volume (ml/m²) | 35 (28, 45) | 29 (20, 40) | <0.001 |

| Δ End-diastolic volume (ml/m²) | −6 (−12, −2) | ||

| End-systolic volume (ml/m²) | 8 (5, 12) | 5 (3, 7) | <0.001 |

| Δ End-systolic volume (ml/m²) | −3 (−5, 0) | ||

| Stroke volume (ml/m²) | 28 (22, 37) | 23 (17, 32) | <0.001 |

| Δ Stroke volume (ml/m²) | −4 (−9, 1) | ||

| Ejection fraction (%) | 78 (71, 84) | 83 (75, 88) | <0.001 |

| Δ Ejection fraction (%) | 5 (−2, 11) | ||

| E wave (cm/s) | 71 (59, 89) | 97 (83, 121) | <0.001 |

| Δ E wave (cm/s) | 25 (8, 44) | ||

| A wave (cm/s) | 73 (60, 91) | 104 (84, 125) | <0.001 |

| Δ A wave (cm/s) | 27 (8, 45) | ||

| Deceleration time (ms) | 185 (160, 250) | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| S wave (cm/s) | 7.5 (6.1, 9.0) | 9.4 (7.6, 11.9) | <0.001 |

| Δ S wave (cm/s) | 2.1 (0.7, 3.3) | ||

| E′ wave (cm/s) | 7.5 (5.9, 9.0) | 9.7 (7.4, 13.8) | <0.001 |

| Δ E′ wave (cm/s) | 3.1 (0.9, 5.0) | ||

| A′ wave (cm/s) | 8.4 (6.5, 11.1) | 11.1 (9.3, 15.5) | <0.001 |

| Δ A′ wave (cm/s) | 2.5 (0.9, 5.1) | ||

| E/E′ | 9.9 (7.0, 14.2) | 9.2 (7.1, 12.8) | 0.270 |

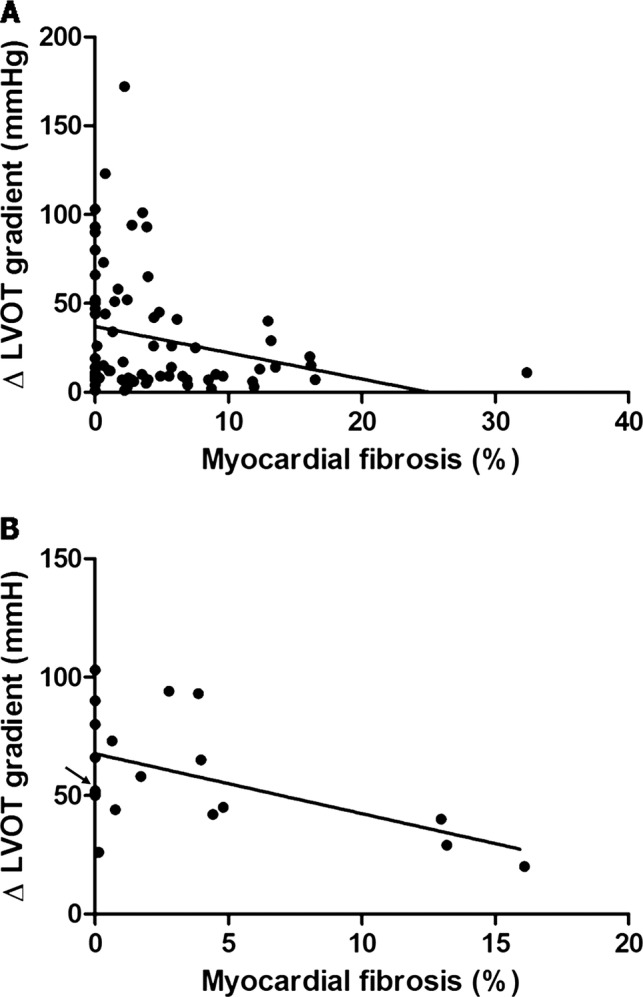

There was no correlation between the extent of fibrosis and maximum LVOT gradient during exercise (r=−0.197, p=0.087). Considering the variation in LVOT gradient during exercise, there was a weak correlation with the extent of fibrosis in the overall population (r=−0.243, p=0.034) and a stronger correlation in patients with an obstructive form of the disease at rest (r=−0.524, p=0.021; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Linear regression analysis between extent of fibrosis and changes in left ventricular (LV) outflow tract gradient during exercise. (A) In the overall population and (B) in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy at rest. Note: the mark indicated by the arrow represents four patients who showed no late-gadolinium enhancement and an increase in LV outflow tract gradient during exercise of 50, 50, 51 and 52 mm Hg, respectively.

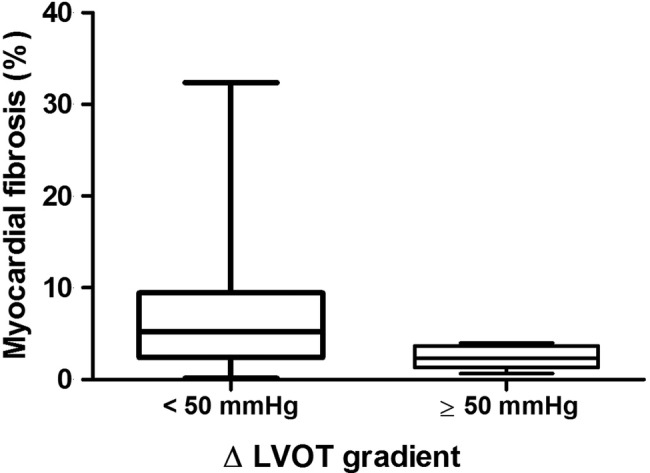

Patients with a maximum gradient during exercise ≥50 mm Hg tended to have a lesser amount of fibrosis than those with a maximum gradient <50 mm Hg; the difference however did not reach significance (1.1% (IQR 0–3.9) vs 4.1% (IQR 0.5–8.2), p=0.089). Patients with an increase in LVOT gradient ≥50 mm Hg had a significantly lesser extent of fibrosis than those with an increase <50 mm Hg (0.7% (IQR 0–2.4) vs 3.2% (IQR 0.2–7.4), p=0.006; figure 2). There was no difference in terms of fibrosis extent between patients with an increase in LVOT gradient ≥ or < than the median value (14 mm Hg) (1.7% (IQR 0–4.6) vs 2.8% (IQR 0–7.0), p=0.330). When dividing the population into quartiles according to LVOT gradient increase during exercise the extent of fibrosis was significantly different: in patients with an increase <8 mm Hg the median value of fibrosis was 3.4% (IQR 2.2–8.6), in patients with an increase between 8 and 13 mm Hg was 1.1% (IQR 0.0–6.6), in patients with an increase between 14 and 46 mm Hg was 4.4% (IQR 0.7–11.6) and in patients with an increase ≥ 47 mm Hg median value of fibrosis was 0.6% (IQR 0.0–2.4, p=0.009).

Figure 2.

Fibrosis extent (expressed as median and IQR) in patients with an increase in exercise gradient < or ≥50 mm Hg.

Discussion

This study shows that myocardial fibrosis (detected as LGE on MRI) may influence the development of LVOT gradient during exercise in patients with HCM and normal EF: patients with higher exercise-induced gradients show a lesser degree of myocardial fibrosis and vice versa (figure 3). This negative association is more evident in patients with an obstructive form at rest.

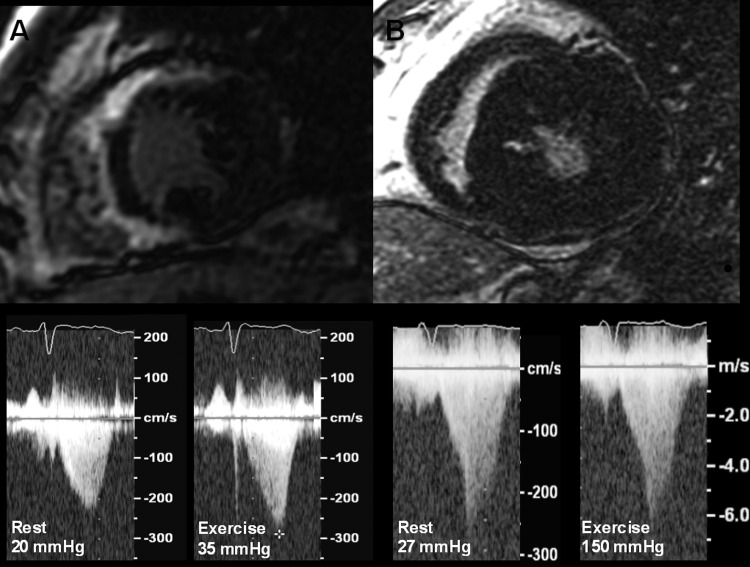

Figure 3.

Myocardial fibrosis and changes in left ventricular (LV) outflow tract gradient during exercise. (A) Patient with a large amount of myocardial fibrosis and modest increase in LV outflow tract gradient. (B) Patient with a limited amount of fibrosis and relevant increase in LV outflow tract gradient during exercise.

In recent years, myocardial fibrosis has been emerging as an important factor in the complex pathophysiology of HCM. It has been suggested that impairment in collagen turnover could be a component of the disease phenotype and that it appears as an early manifestation of sarcomere gene mutations, before the development of overt LV hypertrophy.19 20 When hypertrophy develops, increasing amounts of interstitial fibrosis can be detected non-invasively by gadolinium-enhanced cardiac MRI.6–8 The exact mechanism leading to fibrosis remains unknown but it has been hypothesised that the main triggers for the fibrotic process include molecular factors at the cellular level (induced by sarcomeric mutations), haemodynamic factors (overall ventricular afterload resulting from the sum of LV outflow obstruction and systolic blood pressure), and ischaemia (mainly related to small intramural coronary vessel disease).8 Myocardial fibrosis in HCM has been associated with the risk of life-threatening arrhythmias and with a wide spectrum of systolic dysfunction, ranging from a mild LV EF reduction to the end-stage phase.9–14 The present study confirmed the association between myocardial fibrosis and contractility, assuming that LV systolic function is one of the major determinants of the LVOT gradient increase during effort. The prevalence of myocardial fibrosis (71%) in our study is comparable with that of the largest published series;12 14 in most cases, however, LGE was modest and presented a patchy distribution. Our results therefore support the concept of a continuum of haemodynamic effect of myocardial fibrosis on LV function. Large ‘scar-like’ areas of fibrosis are a determinant of the end-stage evolution, lesser degrees of fibrosis are associated with slight EF reduction,14 15 while even lesser degrees of fibrosis, while not influencing EF at rest, seem to result in a lesser contractility recruitment during exercise, leading to a lower LV outflow gradient. Notably, the effects of myocardial fibrosis were particularly evident among patients with LV outflow gradient already present at rest. Indeed LV contractility is not the only determinant of LV outflow obstruction; excessive length of the anterior mitral leaflet, abnormalities in the subvalvular apparatus and load conditions also play a role.21 In patients with no LV outflow obstruction at rest (related eg, to the large anatomical size of LVOT and/or a non-redundant mitral valve), the increase in contractility could fail to generate a significant LV gradient increase regardless of the amount of myocardial fibrosis.

Study limitations

When interpreting our findings one must consider the low absolute number of patients as well as the fact that the results derived from the analysis of multiple subgroups, even though these were identified with a solid pathophysiological rationale.

The lack of direct haemodynamic measurement of LV pressures limits the pathophysiological interpretation of our data which are essentially based on the behaviour of LV outflow gradient and indexes of ventricular and myocardial function. Also, our study did not include a detailed analysis of the behaviour of LV volumes during exercise and of their correlation with other variables. Indeed, the small absolute values of LV end-systolic volume in this disease during exercise (often below the repeatability threshold) make echocardiography an unreliable technique for this purpose.

Conclusions

In patients with HCM and normal EF at rest, myocardial fibrosis—detected by MRI—is associated with a lower increase in LVOT gradient during exercise, probably due to a lesser degree of myocardial contractility recruitment. This negative association is more evident in patients with an obstructive form at rest.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Contributors: GR, LL, FL, SR, CP, FP, MLBR and RF have substantially contributed to the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; EB, ML and IO drafted the article or critical revision and CR is associated with final approval of the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Maron BJ, Maron MS, Wigle ED, et al. The 50-year history, controversy, and clinical implications of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:191–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott P, McKenna WJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet 2004;363:1881–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maron MS, Olivotto I, Zenovich AG, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is predominantly a disease of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Circulation 2006;114:2232–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah JS, Esteban MTT, Thaman R, et al. Prevalence of exercise-induced left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in symptomatic patients with non-obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart 2008;4:1288–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Autore C, Bernabò P, Barillà CS, et al. The prognostic importance of left ventricular outflow obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy varies in relation to the severity of symptoms. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:1076–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choudhury L, Mahrholdt H, Wagner A, et al. Myocardial scarring in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:2156–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moon JC, McKenna WJ, McCrohon JA, et al. Toward clinical risk assessment in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with gadolinium cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1561–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moon JC, Reed E, Sheppard MN, et al. The histologic basis of late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:2260–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon DH, Smedira NG, Rodriguez ER, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance detection of myocardial scarring in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy correlation with histopathology and prevalence of ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:242–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adabag AS, Maron BJ, Appelbaum E, et al. Occurrence and frequency of arrhythmias in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in relation to delayed enhancement on cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1369–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon DH, Setser RM, Popovic ZB, et al. Association of myocardial fibrosis, electrocardiography and ventricular tachyarrhythmia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a delayed contrast enhanced MRI study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2008;24:617–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Hanlon R, Grasso A, Roughton M, et al. Prognostic significance of myocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:867–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruder O, Wagner A, Jensen CJ, et al. Myocardial scar visualized by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging predicts major adverse events in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:875–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubinshtein R, Glockner JF, Ommen SR, et al. Characteristics and clinical significance of late gadolinium enhancement by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:51–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olivotto I, Maron BJ, Appelbaum E, et al. Spectrum and clinical significance of systolic function and myocardial fibrosis assessed by cardiovascular magnetic resonance in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2010;106:261–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris KM, Spirito P, Maron MS, et al. Prevalence, clinical profile, and significance of left ventricular remodeling in the end-stage phase of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2006;114:216–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spirito P, Bellone P, Harris KM, et al. Magnitude of left ventricular hypertrophy and risk of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1778–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia MJ, Rodriguez L, Ares M, et al. Myocardial wall velocity assessment by pulsed Doppler tissue imaging: characteristic findings in normal subjects. Am Heart J 1996;132:648–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho CY, López B, Coelho-Filho OR, et al. Myocardial fibrosis as an early manifestation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2010;363:552–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lombardi R, Betocchi S, Losi MA, et al. Myocardial collagen turnover in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2003;108:1455–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yacoub MH, El-Hamamsy I, Said K, et al. The left ventricular outflow in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: from structure to function. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2009;2:510–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.