Abstract

Urticaria is a heterogeneous group of disorders, especially acute urticaria and angiooedema can be a medical emergency. This paper summarizes the EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guidelines, the most recent international guidelines from 2009. Patients with urticaria are often not diagnosed and treated appropriately and the guidelines state that clinicians should always aim to provide complete symptom relief. The mainstay of urticaria treatment is the use of modern nonsedating antihistamines, if required up to 4-fold of standard doses.

Keywords: urticaria, acute urticaria, guidelines, nonsedating antihistamines

This article was originally published online on 13 January 2012

Urticaria is a common, heterogeneous group of disorders with a large variety of underlying causes. It is characterized by the appearance of fleeting wheals, which each last 1-24 hours and/or angioedema lasting up to 72 hours. This paper summarizes the EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guidelines from 2009[1, 2] for an outline of the diagnosis and treatment of the disease. Currently, these are the only international guidelines available. These guidelines are the result of a consensus reached during a panel discussion at the 3rd International Consensus Meeting on Urticaria, Urticaria 2008, a joint initiative of the Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), the EU-funded network of excellence, the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN), the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), and the World Allergy Organization (WAO).

Classification of Urticaria on the Basis of its Duration, Frequency, and Causes

The spectrum of clinical manifestations of different urticaria subtypes is very wide. Additionally, 2 or more different subtypes of urticaria can coexist in any given patient. Table 1 presents a classification for clinical use.

Table 1.

Assessment of Disease Activity in Urticaria Patients

| Score | Wheals | Pruritus |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | None | None |

| 1 | Mild (<20 wheals/24 hours) | Mild (present but not annoying or troublesome) |

| 2 | Moderate (20-50 wheals/24 hours) | Moderate (troublesome but does not interfere with normal daily activity or sleep |

| 3 | Intense (>50 wheals/24 hours or large confluent areas of wheals) | Intense (severe pruritus, which is sufficiently troublesome to interfere with normal daily activity or sleep) |

Sum of score: 0-6.

Another important factor the new guidelines point out is assessing disease activity. Where physical triggers are implicated an exact measurement of the intensity of the eliciting factor can be made, for example, the temperature and duration of application in cold urticaria or pressure, and the duration of application until provocation of lesions in delayed pressure urticaria. For nonphysical acute and chronic urticaria, assessing disease activity is more complex. The guidelines propose using scales from 0 to 3. This simple scoring system (Table 1) is based on the assessment of key urticaria symptoms (wheals and pruritus). It is also suitable for evaluation of disease activity by urticaria patients and their treating physicians and it has been validated[3].

As urticaria symptoms frequently change in intensity during the course of a day, overall disease activity is best measured by advising patients to document 24-hour self-evaluation scores for several days.

Diagnosis of Urticaria

Because of the heterogeneity of urticaria and its many subtypes, guidelines for diagnosis might start with a routine patient evaluation, which should comprise a thorough history and physical examination, and the ruling out of severe systemic disease by basic laboratory tests. Specific provocation and laboratory tests should be carried out on an individualized basis on the basis of the suspected cause.

Of all the diagnostic procedures, the most important is to obtain a thorough history including all possible eliciting factors and significant aspects of the nature of the urticaria. Questions suggested by the guidelines are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Suggested Questions

| Number | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | Time of onset of disease |

| 2 | Frequency and duration of wheals |

| 3 | Diurnal variation |

| 4 | Occurrence in relation to weekends, holidays, and foreign travel |

| 5 | Shape, size, and distribution of wheals |

| 6 | Associated angioedema |

| 7 | Associated subjective symptoms of lesion, e.g. itch, pain |

| 8 | Family and personal history regarding urticaria, atopy |

| 9 | Previous or current allergies, infections, internal diseases, or other possible causes |

| 10 | Psychosomatic and psychiatric diseases |

| 11 | Surgical implantations and events during surgery |

| 12 | Gastric/intestinal problems (stool, flatulence) |

| 13 | Induction by physical agents or exercise |

| 14 | Use of drugs (NSAIDs, injections, immunizations, hormones, laxatives, suppositories, ear and eye drops, and alternative remedies) |

| 15 | Observed correlation to food |

| 16 | Relationship to the menstrual cycle |

| 17 | Smoking habits |

| 18 | Type of work |

| 19 | Hobbies |

| 20 | Stress (eustress and distress) |

| 21 | Quality of life related to urticaria and emotional impact |

| 22 | Previous therapy and response to therapy |

The second step is physical examination of the patient. This should include a test for dermographism. Subsequent diagnostic steps will depend on the nature of the urticaria subtype, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Recommended Diagnostic Tests in Frequent Urticaria Subtypes

| Types | Subtypes | Routine Diagnostic Tests (Recommended) | Extended Diagnostic Programme (Suggested) for Identification of Eliciting Factors and for Ruling Out Possible Differential Diagnoses if Indicated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous urticaria | Acute spontaneous urticarial | None | None |

| Chronic spontaneous urticaria | Differential blood count and ESR or CRP omission of suspected drugs(e.g. NSAID) | Test for (i) infectious diseases (e.g. Helicobacter pylon); (ii) type I allergy; (iii) functional autoantibodies; (iv) thyroid hormones and autoantibodies; (v) skin tests including physical tests; (vi) pseudoallergen-free diet for 3 weeks and tryptase, (vii) autologous serum skin test, lesional skin biopsy | |

| Physical urticarial | Cold contact urticarial | Cold provocation and threshold test (ice cube, cold water, cold wind) | Differential blood count and ESR/CRP cryoproteins rule out other diseases, especially infections |

| Delayed pressure urticaria | Pressure test (0.2-1.5 kg/cm[2] for 10 and 20 minutes) | None | |

| Heat contact urticaria | Heat provocation and threshold test (warm water) | None | |

| Solar urticaria | UV and visible light of different wave lengths | Rule out other light-induced dermatoses | |

| Demographic urticaria/urticaria factitia | Elicit demographism | Differential blood count, ESR/CRP | |

| Other urticaria types | Aquagenic urticaria | Wet cloths at body temperature applied for 20 minutes | None |

| Cholinergic urticaria | Exercise and hot bath provocation | None | |

| Contact urticaria | Prick/patch test read after 20 minutes | None | |

| Exercise-induced | According to history exercise test with/without | None | |

| anaphylaxis/urticaria | food but not after a hot bath |

ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Depending on suspected cause.

Unless strongly suggested by patient history, e.g. allergy.

As indication of severe systemic disease.

Treatment of Urticaria

Omission of Eliciting Drugs

Common drugs eliciting and aggravating chronic spontaneous urticaria include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors[1, 2]. If drugs are suspected to cause or aggravate urticaria, they should be omitted or substituted appropriately.

Avoidance of Physical and Other Stimuli in Inducible Urticaria

In patients suffering from inducible urticaria such as cholinergic urticaria, solar urticaria, or cold urticaria, the avoidance of the trigger should be attempted as much as possible.

Treatment of Infectious Agents

In some cases of chronic spontaneous urticaria eradication of infections, such as H. pylori, bowel parasites and bacterial infections of the nasopharynx, have shown to provide a benefit in the management of the disease[1, 2, 4, 5]. However, the eradication of intestinal candida is no longer believed to be of benefit. In addition chronic inflammatory processes such as gastritis, esophageal reflux disease and inflammations of the bile duct and gall bladder are now believed to be potential causative factors and should be managed accordingly[2, 6].

Dietary Modifications

If IgE-mediated food allergy has been identified as a trigger of chronic spontaneous urticaria, the specific allergen should be avoided as much as possible. This should clear the symptoms within 24 to 48 hours. Pseudoallergens can also elicit or aggravate chronic spontaneous urticaria but, in contrast to Typ-I allergens, need to be avoided for at least 3 to 6 months, to provide any benefit.

Symptomatic Treatment

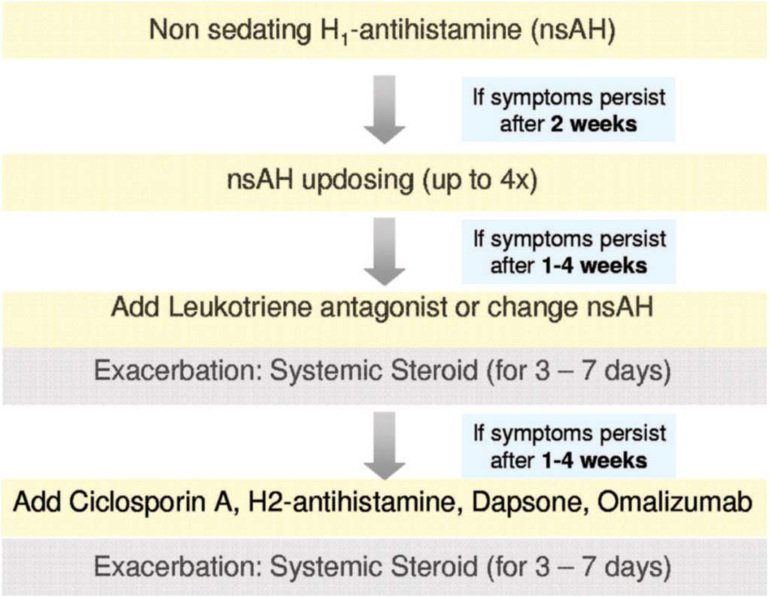

The aim of the symptomatic therapy is to provide complete symptom relief. In general a stepwise approach is followed as illustrated in Figure 1[2].

Figure 1.

Taken from EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline: Management of Urticaria.

Nonsedating antihistamines have a very good evidence for efficacy, a very good safety profile and are low in cost. Increasing the dose of the second generation antihistamines is recommended because of a good safety profile, good evidence of efficacy, and low cost. Although the third treatment step is supported by the benefit of a good safety profile and low to medium-low cost, there is no or insufficient evidence for its efficacy in high quality RCTs. Corticosteroids should only be used in the treatment of acute urticaria or acute flares of chronic spontaneous urticaria. Their long-term use should be avoided outside specialist clinics. In patients with severe urticaria refractory to any of the above measures, ciclosporin can be used as it has an effect on mast-cell mediator release and prevents basophil histamin release. However, because of its medium-high costs, moderate safety, and moderate level of evidence of efficacy, its benefits need to be carefully balanced against the disadvantages. Another option is the use of Omalizumab (anti-IgE) in some cases of chronic spontaneous urticaria, cholinergic-, cold-, or solar urticaria. Its high cost and low level of evidence of efficacy should be carefully considered before introducing the medication. Furthermore, many other treatments have been proposed like dapsone, sulfasalazine, methotrexat, IVIG, interferon, and plasmapharesis but only been tested in uncontrolled trials or case studies and further studies are required to evaluate their effects. Table 4 illustrates the evidence for commonly used drugs.

Table 4.

Modified From EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline: Management of Urticaria

| Urticaria Subtype | Treatment | Quality of Evidence | Strength of Recommendation for Use of Intervention | Alternatives (for Patients Who Do Not Respond to Other Interventions) | Quality of Evidence | Strength of Recommendation for Use of Alternativeintervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. Acute spontaneous urticaria | ns sg H1-AH: l | Low | Strong | Prednisolone, 2 × 20 mg/d* for 4 days | Low | Weak |

| Prednisolone, 50 mg/d* for 3 days | Very low | |||||

| H2-blocker, single dose for 5 days | Very low | |||||

| b. Chronic spontaneous urticarial | ns sg H1-AH | High | Strong | ns sg H1-AH and ciclosporin | High | All weak |

| ns sg H1 and H2-AH cimetidine | Very low | |||||

| - Increase dosage if necessary up to fourfold | Low | Weak | Monotherapy: | |||

| Tricyclic antidepressants (doxepin) | Low | |||||

| Ketotifen | Low | |||||

| Hydroxychloroquine | Very low | |||||

| Dapsone | Very low | |||||

| Sulfasalazine | Very low | |||||

| Methotrexate | Very low | |||||

| Corticosteroids | Very low | |||||

| Other treatment options | ||||||

| Combination therapy: | ||||||

| ns sg H1-AH and stanazolol | Low | |||||

| ns sg H1-AH and zafirlukast | Very low | |||||

| ns sg H1-AH and mycophenolate mofetil | Very low | |||||

| ns sg H1-AH and narrowband UV-B | Very low | |||||

| ns sg H1-AH and omalizumab | Very low | |||||

| Monotherapy: | ||||||

| Oxatomide | Very low | |||||

| Nifedipine | Very low | |||||

| Warfarin | Very low | |||||

| Interferon | Very low | |||||

| Plasmapheresis | Very low | |||||

| Immunoglobulins | Very low | |||||

| Autologous whole blood injection | Very low | |||||

| (ASST positive only) | ||||||

| c. Physical urticaria | In generel for physical urticarias: | High | Strong | Very low | ||

| Avoidance of stimuli | ||||||

| Symptomatic dermographism/Urticaria factitia | ns sg H1-AH: | Low | Weak | Ketotifen (see also chronic urticaria) narrowband UV-B therapy | Very low | All weak |

| Delayed pressure | ns sg H1-AH: cetirizine | Low | All weak | Combination therapy: | All weak | |

| urticaria | ||||||

| Montelukast and ns H1-AH (loratadine) | Very low | |||||

| High dose ns H1-AH | Very low | Monotherapy: | ||||

| Very low | Prednisolone 40-20 mg* | Very low | ||||

| Other treatment options | ||||||

| Combination therapy: | ||||||

| Ketotifen and nimesulide | Very low | |||||

| Monotherapy:Topical clobetasol propionate. | Very low | |||||

| Sulfasalazine | Very low | |||||

| Cold urticaria | ns sg H1-AH | High | Strong | Trial with penicillin i.m./p.o. | Very low | All weak |

| Trial with doxycyline p.o. | Very low | |||||

| Increase dose up to fourfold | Induction of physical tolerance | |||||

| Other treatment options | ||||||

| Cyproheptadine | Very low | |||||

| Ketotifen | Low | |||||

| Montelukast | Very low | |||||

| Solar urticaria | ns H1-AH | Very low | Weak | Induction of physical tolerance | Very low | All weak |

| Other treatment options | ||||||

| Plasmapheresis + PUVA | Very low | |||||

| Photopheresis | Very low | |||||

| Plasma exchange | Very low | |||||

| IVIGs | Very low | |||||

| Omalizumab | Very low | |||||

| d. Special types of inducible urticaria | ||||||

| Cholinergic urticaria | ns H1-AH | Low | Weak | "Exercise tolerance" | Very low | All weak |

| Other treatment options | ||||||

| - Increase dosage if necessary, up to fourfold | Low | Ketotifen, danazol | Very low | |||

| Omalizumab | Very low | |||||

Summary

The new guidelines for urticaria give clear recommendations, on diagnosis and treatment. Further RCTs are required to provide the best possible treatment to patients, who do not respond to first-or second line-treatments.

Acknowledgements

The contents of this article were presented as an invited World Allergy Organization Lecture at the First Middle East Asia Allergy Asthma and Immunology Congress (MEAAAIC) in Dubai, UAE, March 26-29, 2009, as part of the symposium, "Current Concepts in Allergic Rhinitis, Rhinosinusitis and New Developments in Histamine-mediated Diseases."

Schering-Plough provided an educational grant for the symposium.

The authors of the international guidelines are: Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, Canonica GW, Church MK, Giménez-Arnau AM, Grattan CEH, Kapp A, Maurer M, Merk HF, Rogala B, Saini S, Sánchez-Borges M, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Schünemann H, Staubach P, Vena GA, and Wedi B.

References

- 1.Zuberbier T., Bindslev-Jensen C., Canonica G., Church M.K., Gimenez-Arnau A.M., et al. EAACI/GALEN/EDF/WAO guideline: definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1417–1426. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuberbier T., Asero R., Bindslev-Jensen C., Canonica G., Church M.K., et al. EAACI/GALEN/EDF/WAO guideline: management of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1427–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mlynek A, Magerl M, Hanna M, Lhachimi S, Baiardini I, et al. The German version of the chronic urticaria quality-of-life-questionnaire (CUQ2oL): validation and initial clinical findings. Allergy. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Abdou A.G., El Elshayeb, Farag A.G., Elnaidany N.F. Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with chronic urticaria: correlation with pathologic findings in gastric biopsies. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:464–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wedi B., Kapp A. Helicobacter pylori infection in skin diseases: a critical appraisal. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:273–282. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200203040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wedi B., Raap U., Kapp A. Chronic urticaria and infections. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4:387–396. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200410000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]