Summary

Background and objectives

Altered levels of atherogenic lipoproteins have been shown to be common in mild kidney dysfunction. This study sought to determine the associations between plasma lipids (including LDL particle distribution) and subclinical atherosclerosis measured by the common carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) across levels of estimated GFR (eGFR) and to assess whether inflammation modifies these associations.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Cross-sectional analyses of 6572 participants in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis enrolled from 2000 to 2002 were performed.

Results

CKD, defined as eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, was present in 853 individuals (13.0%). Associations of total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) with IMT were J shaped, particularly among participants with CKD (P value for interaction, P=0.01). HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) and small-dense LDL-C were consistently and linearly associated with IMT across levels of eGFR. The results showed differences in IMT of −21.41 (95% confidence interval, −41.00, −1.57) in eGFR ≥60 and −58.49 (−126.61, 9.63) in eGFR <60 per unit difference in log-transformed HDL-C, and 4.83 (3.16, 6.50) in eGFR ≥60 and 7.48 (1.45, 13.50) in eGFR <60 per 100 nmol/L difference in small-dense LDL. Among participants with CKD, inflammation significantly modified the associations of total cholesterol and LDL-C with IMT (P values for interaction, P<0.01 and P<0.001, respectively).

Conclusions

Compared with total cholesterol and LDL-C, abnormalities in HDL-C and small-dense LDL-C are more strongly and consistently associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in CKD. Inflammation modifies the association between total cholesterol and LDL-C with IMT.

Introduction

CKD affects >26 million adults, or approximately 13% of the adult US population (1). Atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk factors are highly prevalent in CKD patients and their relationships to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease parallel those of the general population (2,3). The association between plasma lipids and cardiovascular risk in CKD, however, has been difficult to establish. A lipid profile with often normal levels of total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), U-shaped relationships between lipids and coronary heart disease (CHD), and heterogeneous results of clinical trials testing lipid-lowering therapies in CKD (4–6) have contributed to this difficulty.

Patients with CKD typically have high concentrations of triglycerides and low concentrations of HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), often with normal total cholesterol (7,8). Recent evidence demonstrates that individuals with CKD have increased concentrations of the highly atherogenic small-dense LDL-C particles, and intermediate density lipoprotein (IDL) particles (9,10). It is not known whether elevated concentrations of these lipoprotein particles in patients with CKD are associated with an increased risk of CHD.

Studies assessing the association between lipids and cardiovascular disease in individuals with severe CKD and ESRD have consistently found J-shaped relationships (11,12). These findings may be explained by the high prevalence of inflammation and malnutrition present in individuals with low lipid levels and severe CKD and ESRD (12,13). Less is known about the prevalence of inflammation and its role in modifying the association between plasma lipids and cardiovascular outcomes at higher estimated GFR (eGFR) values (moderate CKD).

We used data collected at the first examination of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) to investigate the associations of an extended lipid panel (including lipoprotein particle concentrations) with common carotid intima-media thickness (IMT), across different levels of kidney function, and to determine whether the presence of inflammation modifies these associations.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

MESA is a population-based prospective cohort study designed to investigate the prevalence and progression of subclinical cardiovascular disease. Its design has been described previously (14). For these analyses, we excluded participants without a measurement of serum creatinine (n=29), participants in whom the urinary albumin/creatinine ratio (UACR) was >3000 mg/g (nephrotic proteinuria) (n=33), participants with missing values of any of the assessed lipid components (n=99), and those who did not have carotid ultrasound measurements (n=81).

Measurements

Plasma Lipids and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Lipoprotein Measurements.

The concentrations of total cholesterol, HDL-C, and triglycerides were measured in EDTA plasma using a cholesterol oxidase method (for total cholesterol and HDL-C) and a triglyceride (GB) reagent. LDL-C was calculated using the Friedewald equation (15). In 86 individuals, triglyceride levels were >400 mg/dl. In these individuals, the concentration LDL-C could not be estimated and were excluded from the analysis.

Lipoprotein particle concentrations were measured by proton nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (16,17). This method quantifies particle concentrations of lipoproteins of different size by measuring their distinctive signals emanating from lipoprotein subclasses based on their terminal methyl group. We used the following concentrations in nanomoles per liter of the following subclasses according to their size: small-dense LDL (18.0–20.5 nm), large LDL (20.6–23 nm), and IDL (24–27 nm).

IMT.

High-resolution B-mode carotid ultrasonography was performed in the entire cohort at baseline. The mean (average IMT) of four measurements of the maximum common carotid artery IMT was used: the near and far walls in the common carotid artery on both the left and right sides. At each field center, trained technicians used the Logiq 700 ultrasound device to record images. An ultrasound-reading center at the Department of Radiology of Tufts–New England Medical Center performed the IMT readings.

Kidney Function.

The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation, based on a centrally calibrated serum creatinine assay, was used to estimate GFR. The validity of this formula in estimating measured GFR has been shown elsewhere (18). GFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was defined as CKD. Serum creatinine was measured by rate reflectance spectrophotometry at a central laboratory with a coefficient of variation of 2.2%.

Inflammation.

Concentrations of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) were measured using the BNII nephelometer at a central laboratory with an intra-assay coefficient of variation range from 2.3% to 4.4% and interassay coefficient of variation from 2.1% to 5.7%; IL-6 was measured by ultrasensitive ELISA at a central laboratory with a coefficient of variation of 6.3%. Inflammation was defined as ≥90th percentile levels of either IL-6 or hsCRP, corresponding to concentrations of ≥3.0 pg/ml for IL-6 and ≥9 mg/L for hsCRP, similarly to previous analyses (12,13).

Adjustment.

All analyses were adjusted for the following: age, race, sex, hypertension (if diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg, systolic BP ≥140 mmHg, or use of antihypertensive medication), diabetes (normal if fasting glucose <110 mg/dl, impaired glucose tolerance if fasting glucose 110–125 mg/dl, untreated diabetes if fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dl and no report of oral hypoglycemic medication or insulin use, and treated diabetes if fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dl and report of insulin or oral hypoglycemic medication use), continuous body mass index (BMI), continuous UACR, current smoking, and use of lipid-lowering therapy. Analyses of LDL-C were also adjusted for triglycerides and HDL-C. For each NMR lipoprotein particle analysis, we adjusted for other NMR particles in addition to HDL-C and triglycerides. No adjustment for other lipid measurements was done for analyses of total cholesterol.

Effect modification in the association of lipids and IMT across eGFR categories was tested by the presence of diabetes or by the presence of the metabolic syndrome defined by ≥3 of the following: waist-hip circumference ratio >102 cm for women and >88 cm for men; triglyceride levels >150 mg/dl; HDL-C <40 mg/dl for women and <50 mg/dl for men; hypertension indicated by diastolic BP >85 mmHg, systolic BP >130 mmHg, or use of a BP medication; and impaired fasting glucose >110 mg/dl.

Statistical Analyses

To determine the distribution of IMT, we assessed the goodness of fit of the normal and the log-normal cumulative distribution function and probability density function of the estimated IMT by graphically comparing it with the cumulative distribution function and probability density function of the empirical IMT. The Fisher’s exact test and the Kruskal–Wallis test were used to compare categorical and continuous variables across levels of kidney function, respectively. Normal linear regression was used to model the association between plasma lipids and IMT. We specifically tested for nonlinear relationships by a graphical comparison with nonparametric models and residual analyses for all lipid components analyzed. If nonlinear associations were present, we evaluated linear spline models with different knots and second- and third-degree polynomials models and selected the best-fitting model based on the Akaike information criterion. Restricted cubic spline models were used for the graphic display of these associations. Likelihood ratio tests were used to compare models with and without interaction terms to test for heterogeneity of the association between plasma lipids and IMT by level of kidney function. Similarly, likelihood ratio tests were used to compare models by level of inflammation.

In sensitivity analyses, we used a cystatin-C–based equation to estimate GFR, excluded individuals with an eGFR ≤30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, excluded individuals on current lipid-lowering therapy (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2), and used a combined measurement of the common and internal carotid arteries. In addition, we used different definitions of inflammation, separately analyzing hsCRP and IL-6 and using a different cutoff for hsCRP (10 mg/L).

All analyses were performed with Stata software (version 11.2; StataCorp, College Station, TX) and R software (version 2.12.1; R Development Core Team).

Results

A total of 6572 individuals (96% of the cohort) met the eligibility criteria and were included in the study. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population across three levels of kidney function are shown in Table 1. Overall, 853 individuals (13.0%) had CKD (eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), with the vast majority of these (97%) having moderate CKD (eGFR 30–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Lower eGFR was associated with older age, higher proportions of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, and greater use of lipid-lowering medications.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 6572 participants in the MESA cohort by levels of kidney function

| Characteristic | eGFR ≥60 (n=5719) | eGFR 45–59 (n=709) | eGFR <45 (n=144) | P for Differencea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 2721 (48) | 311 (44) | 66 (46) | 0.17 |

| Race | <0.001 | |||

| Black | 1600 (28) | 168 (24) | 45 (32) | |

| Chinese | 689 (12) | 80 (11) | 14 (10) | |

| Hispanic | 1294 (23) | 111 (16) | 30 (21) | |

| White | 2136 (37) | 350 (49) | 55 (38) | |

| Age (yr) | 60 (53–68) | 71 (65–77) | 75 (68–79) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.5 (24.4–31.1) | 27.6 (24.7–31.2) | 28.3 (25.2–31.9) | 0.14 |

| Current smoker | 782 (14) | 45 (6) | 10 (7) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 679 (12) | 95 (13) | 35 (24) | <0.001 |

| Biguanide use | 280 (5) | 41 (6) | 4 (3) | |

| Sulfonylurea use | 297 (5) | 46 (6) | 13 (9) | |

| Hypertension | 2353 (41) | 453 (64) | 123 (85) | <0.001 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor use | 168 (3) | 41 (6) | 15 (10) | |

| β-blocker use | 447 (8) | 103 (15) | 29 (20) | |

| Use of any lipid-lowering medication | 836 (15) | 176 (25) | 41 (29) | <0.001 |

| Statin use | 771 (13) | 162 (23) | 37 (26) | |

| Lipid levels (mg/dl) | ||||

| Total cholesterol | 192 (170–215) | 192 (170–216) | 191 (169–216) | 0.95 |

| LDL-C | 116 (96–136) | 113 (95–137) | 113 (93–135) | 0.30 |

| HDL-C | 48 (41–59) | 50 (41–60) | 44 (37–57) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides | 109 (77–157) | 116 (81–162) | 122 (91–189) | <0.001 |

| Lipoprotein particle concentration (nmol/L) | ||||

| Small-dense LDL | 518 (113–798) | 489 (105–776) | 563 (122–817) | 0.06 |

| Large LDL | 601 (426–764) | 596 (414–775) | 518 (380–692) | 0.03 |

| IDL | 102 (51–175) | 112 (53–175) | 117 (51–188) | 0.14 |

| High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 1.8 (0.8–4.2) | 2.1 (1.0–4.5) | 2.6 (1.3–5.7) | <0.001 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 1.2 (0.7–1.8) | 1.4 (1.0–2.1) | 1.5 (1.1–2.2) | <0.001 |

| Urinary albumin/creatinine ratio (mg/g) | 5.1 (3.3–10.1) | 6.2 (3.6–14.8) | 16.4 (4.5–107.8) | <0.001 |

| Intima-media thickness (μm) | 830 (730–960) | 910 (800–1040) | 940 (830–1060) | <0.001 |

Data are n (%) or median (interquartile range). MESA, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; eGFR, estimated GFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2); LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; IDL, intermediate density lipoprotein.

P values based on Fisher’s exact test and the Kruskal–Wallis test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Association of Lipid Levels with Kidney Function

Small differences across levels of kidney function were seen for total cholesterol and LDL-C concentrations. In contrast, lower eGFR was associated with higher levels of triglycerides and small-dense LDL, and lower levels of HDL-C and large LDL. Higher concentrations of inflammatory markers were seen in those with lower eGFR.

Association of Lipid Levels with IMT across Levels of Kidney Function

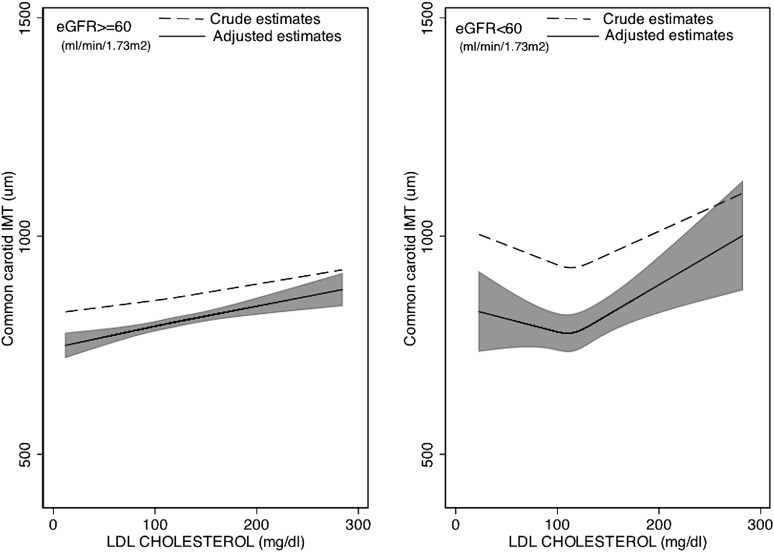

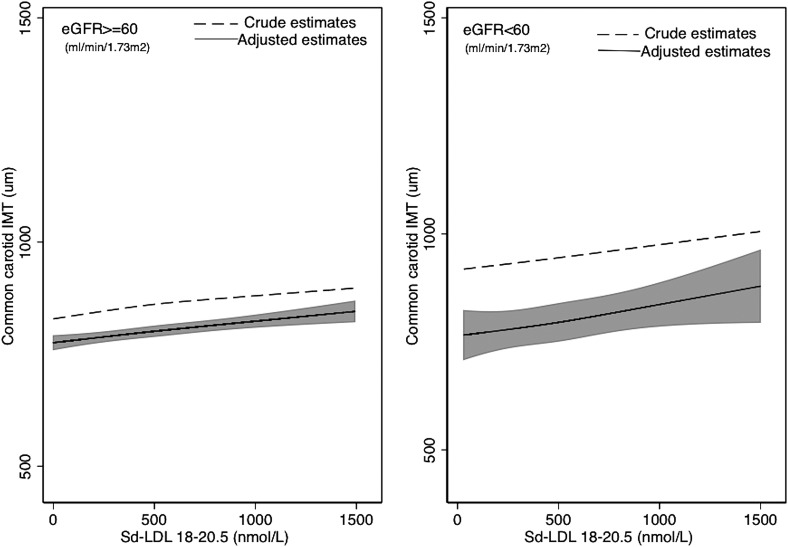

Associations of lipoproteins and NMR lipoprotein particle concentrations and IMT across two levels of kidney function (eGFR ≥60 and eGFR <60) are shown in Table 2. An extension of this table with a further stratification of those with eGFR <60 into two categories (eGFR 45–59 and eGFR <45) is presented in Supplemental Table 3. There was a statistically significant difference in the crude and adjusted associations between total cholesterol and LDL-C and IMT across levels of kidney function. Specifically, J-shaped associations were evident in CKD individuals, whereby higher lipid levels were associated with lower IMT values at total cholesterol <200 mg/dl and LDL-C concentrations <130 mg/dl, respectively, but higher lipid levels were associated with greater IMT values above these cut-offs, (Figure 1 and Table 2). Furthermore, stronger associations between HDL-C and IMT and between small-dense LDL and IMT (and Figure 2 and Table 2) were observed in those with reduced kidney function compared with those with normal kidney function. However, tests for interaction were not significant (P values for interaction, P=0.10 and P=0.12 for HDL-C and small-dense LDL, respectively). This pattern was even more pronounced when CKD was further stratified into one additional category (Supplemental Table 1) (P values for interaction, P=0.04 and P<0.01 for HDL-C and small-dense LDL, respectively). The differences in the associations of triglycerides, large LDL-C, and IDL with IMT across levels of kidney function were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Adjusted estimates and 95% confidence intervals of the difference in common carotid artery intima-media thickness (in micrometers) per specified differences in lipid particle concentrations, by level of kidney function

| Lipid Particle | eGFR ≥60 (n=5719) | eGFR <60 (n=853) | P for Interactiona |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol per 10 mg/dlb | 0.01 | ||

| <200 mg/dl | 2.97 (0.71, 5.23) | −4.89 (−12.98, 3.20) | |

| ≥200 mg/dl | 4.79 (2.40, 7.18) | 13.13 (4.82, 21.42) | |

| LDL-C per 10 mg/dlc | 0.01 | ||

| <130 mg/dl | 4.65 (2.27, 7.04) | −2.53 (−11.46, 6.09) | |

| ≥130 mg/dl | 4.76 (2.05, 7.47) | 15.91 (6.34, 25.49) | |

| Log HDL-C | −21.41 (−41.00, −1.57) | −58.49 (−126.61, 9.63) | 0.10 |

| Log triglycerides | 4.65 (−5.41, 14.72) | −2.58 (−38.97, 33.82) | 0.42 |

| NMR lipids | |||

| Small-dense LDL per 100 nmol/L | 4.83 (3.16, 6.50) | 7.48 (1.45, 13.50) | 0.12 |

| Large-dense LDL per 100 nmol/L | 6.21 (4.08, 8.34) | 12.18 (4.51, 19.86) | 0.81 |

| Log IDL | 0.53 (−3.59, 4.65) | 2.99 (−12.88, 18.86) | 0.78 |

Adjusted for age (years), sex, race/ethnicity, lipid-lowering medication use, presence of diabetes mellitus, presence of hypertension, log-transformed body mass index, log-transformed urinary albumin/creatinine ratio, smoking status (current, former, never smoker), log-transformed high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and log-transformed IL-6. eGFR, estimated GFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2); LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; IDL, intermediate density lipoprotein.

P values testing for the null hypothesis that all slopes across eGFR strata are identical in linear spline models.

Continuous estimates presented before and after a linear spline knot at 200 mg/dl for eGFR ≥60 (<200, n=3397; ≥200, n=2322) and for eGFR <60 (<200, n=513; ≥200, n=340).

Continuous estimates presented before and after a linear spline knot at 130 mg/dl for eGFR ≥60 (<130, n=3851; ≥130, n=1868) and for eGFR <60(<130, n=596; ≥130, n=257).

Figure 1.

Crude and adjusted estimates of the association between LDL cholesterol and IMT (in micrometers). Restricted cubic spline model with knots at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles for LDL cholesterol. The shaded area is the 95% confidence interval for the adjusted restricted cubic spline model. Adjusted for age (years), sex, race/ethnicity, lipid-lowering medication use, presence of diabetes mellitus, presence of hypertension, log-transformed body mass index, log-transformed urinary albumin/creatinine ratio, smoking status (current, former, never smoker), log-transformed triglycerides, log-transformed HDL cholesterol, log-transformed high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and log-transformed IL-6. eGFR, estimated GFR; IMT, intima-media thickness.

Figure 2.

Crude and adjusted estimates of the association between small-dense LDL and IMT (in micrometers). Restricted cubic spline model with knots at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles for small-dense LDL. The shaded area is the 95% confidence interval for the adjusted restricted cubic spline model. Adjusted for age (years), sex, race/ethnicity, lipid-lowering medication use, presence of diabetes mellitus, presence of hypertension, log-transformed body mass index, log-transformed urinary albumin/creatinine ratio, smoking status (current, former, never smoker), log-transformed triglycerides, log-transformed HDL cholesterol, large LDL, log-transformed intermediate density lipoprotein, log-transformed high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and log-transformed IL-6. eGFR, estimated GFR; IMT, intima-media thickness; Sd-LDL, small-dense LDL.

Effect Modification by Inflammation

Inflammation was found in 17.4%, 20.9%, and 24. 3% (P value for difference, P=0.01) of individuals in eGFR categories of ≥60, 45–59, and <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively. Compared with those without CKD (eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), log-transformed hsCRP, log-transformed IL-6, and the presence of inflammation were more strongly associated with IMT in participants with CKD (Supplemental Table 4). The presence of inflammation was associated with lower concentrations of total cholesterol, LDL-C, and large LDL regardless of CKD (Supplemental Table 5). This pattern, however, was not evident for HDL-C, triglycerides, and small-dense LDL, which differed only minimally across inflammation categories and levels of kidney function.

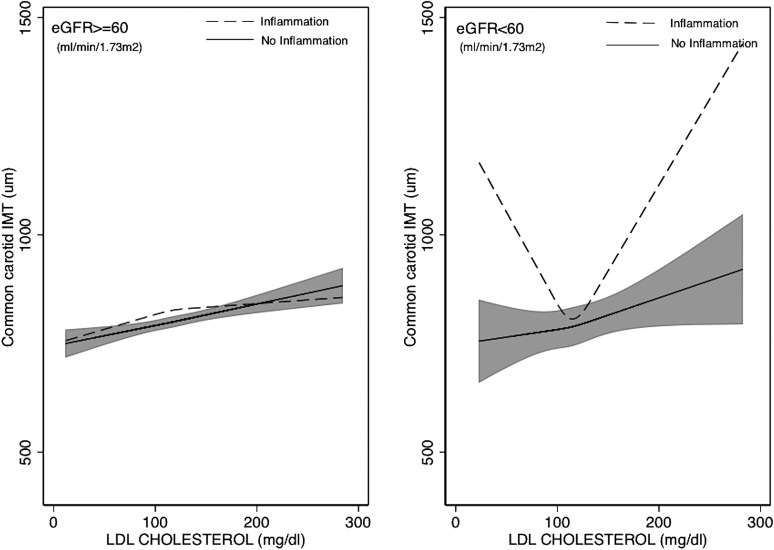

As shown in Figure 3 and Table 3, the J-shaped association of total cholesterol and LDL-C with IMT observed among individuals with CKD was limited to individuals with inflammation. Specifically, in individuals without inflammation, the association between these lipid particles and IMT was similar across levels of kidney function. In contrast, among individuals with inflammation and eGFR <60, associations were sharply U shaped and statistically significantly different from those with eGFR<60 without inflammation (P values for interaction, P=0.01 and P=0.001 for total cholesterol and LDL-C, respectively).

Figure 3.

Adjusted estimates of the association between LDL cholesterol and IMT (in micrometers) according to level of kidney function and presence of inflammation. Restricted cubic spline model with knots at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles for LDL cholesterol. The shaded area is the 95% confidence interval for the adjusted restricted cubic spline model. Adjusted for age (years), sex, race/ethnicity, lipid-lowering medication use, presence of diabetes mellitus, presence of hypertension, log-transformed body mass index, log-transformed urinary albumin/creatinine ratio, smoking status (current, former, never smoker), log-transformed triglycerides, and log-transformed HDL cholesterol. Inflammation is defined as the ≥90th percentile of either IL-6 (≥3 pg/ml) or high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (≥9 mg/L). eGFR, estimated GFR; IMT, intima-media thickness.

Table 3.

Adjusted estimates and 95% confidence intervals of the difference in common carotid artery intima-media thickness (in micrometers) per specified differences in lipid particle concentrations according to level of kidney function and presence of inflammation

| Lipid Particle | eGFR ≥60 (n=5719)a | Pb | eGFR<60 (n=853)c | Pb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Inflammation (n=4726) | Inflammation (n=993) | No Inflammation (n=670) | Inflammation (n=183) | |||

| Total cholesterol per 10 mg/dl | 0.28 | <0.01 | ||||

| <200 mg/dl | 2.51 (0.02, 5.00) | 5.71 (0.62, 10.81) | 1.88 (−6.35, 10.13) | −25.90 (−45.53, −6.48) | ||

| ≥200 mg/dl | 5.65 (3.08, 8.23) | 1.23 (−5.01, 7.48) | 8.35 (1.07, 16.60) | 38.18 (13.87, 62.49) | ||

| LDL-C per 10 mg/dl | 0.65 | <0.001 | ||||

| <130 mg/dl | 4.41 (1.77, 7.05) | 5.17 (−0.52, 10.87) | 4.52 (-4.32, 13.37) | −26.02 (−48.70, −3.35) | ||

| ≥130 mg/dl | 5.44 (2.52, 8.37) | 2.04 (−5.47, 9.56) | 10.07 (0.63, 19.51) | 42.04 (10.58, 73.50) | ||

| Log HDL-C | −14.15 (−35.90, 7.60) | −52.95 (−102.09, −3.81) | 0.20 | −45.39 (−115.92, 25.13) | −42.72 (−240.86, 155.4) | 0.96 |

| Log triglycerides | 3.02 (−7.99, 14.03) | 10.69 (−14.94, 36.31) | 0.48 | 9.70 (−27.83, 47.22) | −16.90 (−128.97, 95.19) | 0.30 |

| NMR lipids | ||||||

| Small-dense LDL per 100 nmol/L | 5.08 (3.25, 6.92) | 3.28 (−0.01, 7.39) | 0.89 | 7.62 (1.42, 13.82) | 3.10 (−14.59, 20.77) | 0.61 |

| Large LDL per 100 nmol/l | 5.85 (3.50, 8.19) | 7.45 (2.26, 12.63) | 0.89 | 16.45 (8.32, 24.58) | 0.60 (−19.86, 21.04) | 0.18 |

| Log IDL cholesterol | 0.27 (−4.13, 4.67) | 2.15 (−9.63, 13.94) | 0.66 | −4.88 (−20.91, 11.14) | 43.66 (−7.64, 94.96) | 0.38 |

Adjusted for age (years), sex, race/ethnicity, lipid-lowering medication use, presence of diabetes mellitus, presence of hypertension, log-transformed body mass index, log-transformed urinary albumin/creatinine ratio, and smoking status (current, former, never smoker). Inflammation is defined as the ≥90th percentile of either IL-6 (≥3 pg/ml) or high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (≥9 mg/L). eGFR, estimated GFR; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; IDL, intermediate density lipoprotein.

No inflammation (<200, n=2775; ≥200, n=1951) and inflammation (<200, n=622; ≥200, n=371) for total cholesterol; no inflammation (<130, n=3142; ≥130, n=1584) and inflammation (<130, n=709; ≥130, n=284) for LDL-C.

P values are for interaction.

No inflammation (<200, n=391; ≥200, n=279) and inflammation (<200, n=122; ≥200, n=61) for total cholesterol; no inflammation (<130, n=462; ≥130, n=208) and inflammation (<130, n=134; ≥130, n=49) for LDL-C.

Results of sensitivity analyses were consistent with the main findings.

Discussion

In this study, we found that reduced kidney function is associated with higher concentrations of the highly atherogenic small-dense LDL and triglycerides, lower concentrations of large LDL-C particles, and lower concentrations of HDL-C. Moreover, estimates of the association of small-dense LDL-C and HDL-C with IMT were stronger with lower eGFR. In contrast, associations of total cholesterol and LDL-C with IMT were J shaped, with inverse associations at low lipid concentrations in individuals with CKD. These J-shaped associations were limited to individuals with CKD and inflammation.

We believe that this study contributes to the knowledge of the mechanisms of atherogenesis in CKD. We show that atherogenic lipids other than LDL-C (which is not elevated in CKD) are more consistently associated with atherosclerosis, and that the presence of inflammation (which is prevalent at early CKD stages) is closely linked with the distribution of lipids and with their association with subclinical atherosclerosis in CKD.

The finding of a stronger relationship of small-dense LDL and HDL-C with IMT in the presence of lower kidney function builds upon previous research (9,10) that showed significantly higher concentrations of these particles in individuals with mildly impaired kidney function despite normal concentrations of total cholesterol and LDL-C. The fact that the associations of these lipid particles with IMT are stronger with lower eGFR suggests that the measurement of these particles may prove useful in explaining at least in part the increased atherosclerotic cardiovascular burden in individuals with CKD. Alternatively, apo-B, which is highly correlated with small-dense LDL (19), or the ratio of apo-B to apo-A1 may be a better marker of cardiovascular risk than total cholesterol and LDL-C, especially in individuals with normal and low LDL-C concentrations (20,21).

The J-shaped associations that were found relating total cholesterol and LDL-C with IMT are consistent with previous studies that have shown similar associations between severe CKD and ESRD and clinical cardiovascular disease endpoints (11–13,22). J-shaped relationships between lipid levels and cardiovascular outcomes have been shown to exist in physiologic processes such as aging and in chronic pathologic states such as malignancies and congestive heart failure (23–28). The high prevalence of inflammation and malnutrition in these conditions is among the potential explanations for these paradoxical relationships (29–31). In our study of largely asymptomatic individuals without clinical cardiovascular disease and with very low rates of underweight individuals with a BMI <18.5 present in 0.87% (n=57) and 0.82% (n=7) of those with eGFR ≥60 and <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively, we were able to show these J-shaped associations and demonstrate the high prevalence of inflammation in early CKD stages, its association with IMT, as well as its role in modifying the association of total cholesterol and LDL-C with IMT.

Results of randomized controlled clinical trials assessing the effects of LDL-C–lowering therapies on CKD and ESRD have been inconsistent. Trials conducted exclusively in ESRD patients receiving renal replacement therapy have shown a lack of benefit of statin therapy on cardiovascular outcomes (4–6). Recently, however, the Study of Heart and Renal Protection (SHARP) observed a significant reduction in major atherosclerotic events in patients with moderate and severe CKD receiving a combination of simvastatin and ezetimibe (32).

Our findings do not conflict with the benefit that was shown in the SHARP trial of lowering LDL-C in individuals with CKD. First, in the SHARP trial, the effectiveness of the combined treatment was markedly reduced in individuals with total cholesterol and LDL-C concentrations of <212 and 117 mg/dl, respectively, which are the usual values observed in individuals with CKD (22) and ESRD (12). Second, the fact that a combination therapy (simvastatin and ezetimibe)—rather than monotherapy with a statin—was used as the active treatment may have been more effective in targeting non-LDL-C–related pathways, such as a greater increase in HDL-C (33). As we have shown here, the negative association between HDL-C and IMT becomes stronger with a reduction in kidney function. However, the benefit derived from the LDL-C–lowering effect from ezetimibe compared with other therapies is controversial (34,35). Finally, the inverse association of total cholesterol and LDL-C with IMT may not represent a benefit from higher lipid concentrations, but rather reflect increased severity of CKD. In our study, individuals with J-shaped associations had higher concentrations of clinically significant inflammation, which is known to significantly increase the cardiovascular disease risk (36). Thus, targeting these individuals for aggressive treatment of modifiable risk factors may prove beneficial in CKD.

Important limitations of this study include its cross-sectional nature. With this design, temporal relationships between variables cannot be assessed. Nonetheless, even for a longitudinal study with serial measures of eGFR, plasma lipids, and IMT, establishing temporal relationships for these variables may prove challenging given the possibility of bi-directional associations. In addition, IMT is a surrogate marker of CHD and although it has been shown to be an independent predictor of clinical cardiovascular outcomes (37–39), inferences derived from surrogate markers may not apply to clinical events. Thus, our results should be confirmed using clinical cardiovascular outcomes. However, the main aim of this study was to assess the association of plasma lipids and inflammation with atherosclerosis in CKD. Finally, there were very few individuals with severe CKD (eGFR <30) and very high lipid measurements (total cholesterol >300 and LDL-C >200), and thus the external validity of our findings with regard to these population groups is limited.

In summary, our findings suggest that in individuals with moderate CKD and free of clinical cardiovascular disease, lipid abnormalities other than total cholesterol and LDL-C are highly prevalent and strongly associated with subclinical atherosclerosis. The relationship of total cholesterol and LDL-C with IMT appeared to be modified by the high prevalence of inflammation in individuals with moderate CKD. Future studies should examine whether incorporation of these lipid measurements helps to explain the increased clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular burden in CKD.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff and participants of the MESA study for their contributions.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.02090212/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 298: 2038–2047, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muntner P, Hamm LL, Kusek JW, Chen J, Whelton PK, He J: The prevalence of nontraditional risk factors for coronary heart disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 140: 9–17, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muntner P, He J, Astor BC, Folsom AR, Coresh J: Traditional and nontraditional risk factors predict coronary heart disease in chronic kidney disease: Results from the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 529–538, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fellström BC, Jardine AG, Schmieder RE, Holdaas H, Bannister K, Beutler J, Chae DW, Chevaile A, Cobbe SM, Grönhagen-Riska C, De Lima JJ, Lins R, Mayer G, McMahon AW, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Samuelsson O, Sonkodi S, Sci D, Süleymanlar G, Tsakiris D, Tesar V, Todorov V, Wiecek A, Wüthrich RP, Gottlow M, Johnsson E, Zannad F, AURORA Study Group : Rosuvastatin and cardiovascular events in patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 360: 1395–1407, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wanner C, Krane V, März W, Olschewski M, Mann JF, Ruf G, Ritz E, German Diabetes and Dialysis Study Investigators : Atorvastatin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 353: 238–248, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holdaas H, Fellström B, Jardine AG, Holme I, Nyberg G, Fauchald P, Grönhagen-Riska C, Madsen S, Neumayer HH, Cole E, Maes B, Ambühl P, Olsson AG, Hartmann A, Solbu DO, Pedersen TR, Assessment of LEscol in Renal Transplantation (ALERT) Study Investigators : Effect of fluvastatin on cardiac outcomes in renal transplant recipients: A multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 361: 2024–2031, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagdade J, Casaretto A, Albers J: Effects of chronic uremia, hemodialysis, and renal transplantation on plasma lipids and lipoproteins in man. J Lab Clin Med 87: 38–48, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagdade JD, Porte D. JrBierman EL: Hypertriglyceridemia. A metabolic consequence of chronic renal failure. N Engl J Med 279: 181–185, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Boer IH, Astor BC, Kramer H, Palmas W, Seliger SL, Shlipak MG, Siscovick DS, Tsai MY, Kestenbaum B: Lipoprotein abnormalities associated with mild impairment of kidney function in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 125–132, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Boer IH, Astor BC, Kramer H, Palmas W, Rudser K, Seliger SL, Shlipak MG, Siscovick DS, Tsai MY, Kestenbaum B: Mild elevations of urine albumin excretion are associated with atherogenic lipoprotein abnormalities in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Atherosclerosis 197: 407–414, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovesdy CP, Anderson JE, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Inverse association between lipid levels and mortality in men with chronic kidney disease who are not yet on dialysis: Effects of case mix and the malnutrition-inflammation-cachexia syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 304–311, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Coresh J, Eustace JA, Longenecker JC, Jaar B, Fink NE, Tracy RP, Powe NR, Klag MJ: Association between cholesterol level and mortality in dialysis patients: Role of inflammation and malnutrition. JAMA 291: 451–459, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Contreras G, Hu B, Astor BC, Greene T, Erlinger T, Kusek JW, Lipkowitz M, Lewis JA, Randall OS, Hebert L, Wright JT, Jr, Kendrick CA, Gassman J, Bakris G, Kopple JD, Appel LJ, African-American Study of Kidney Disease, and Hypertension Study Group : Malnutrition-inflammation modifies the relationship of cholesterol with cardiovascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 2131–2142, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR, Jr, Kronmal R, Liu K, Nelson JC, O’Leary D, Saad MF, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP: Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: Objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol 156: 871–881, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS: Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 18: 499–502, 1972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mora S, Szklo M, Otvos JD, Greenland P, Psaty BM, Goff DC, Jr, O’Leary DH, Saad MF, Tsai MY, Sharrett AR: LDL particle subclasses, LDL particle size, and carotid atherosclerosis in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Atherosclerosis 192: 211–217, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otvos JD: Measurement of lipoprotein subclass profiles by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Clin Lab 48: 171–180, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J, CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kathiresan S, Otvos JD, Sullivan LM, Keyes MJ, Schaefer EJ, Wilson PWF, D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS, Robins SJ: Increased small low-density lipoprotein particle number: A prominent feature of the metabolic syndrome in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 113: 20–29, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walldius G, Jungner I, Holme I, Aastveit AH, Kolar W, Steiner E: High apolipoprotein B, low apolipoprotein A-I, and improvement in the prediction of fatal myocardial infarction (AMORIS study): A prospective study. Lancet 358: 2026–2033, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, Lisheng L, INTERHEART Study Investigators : Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet 364: 937–952, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chawla V, Greene T, Beck GJ, Kusek JW, Collins AJ, Sarnak MJ, Menon V: Hyperlipidemia and long-term outcomes in nondiabetic chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1582–1587, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP, Derose SF, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC: Racial and survival paradoxes in chronic kidney disease. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 3: 493–506, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horwich TB, Hamilton MA, Maclellan WR, Fonarow GC: Low serum total cholesterol is associated with marked increase in mortality in advanced heart failure. J Card Fail 8: 216–224, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chao FC, Efron B, Wolf P: The possible prognostic usefulness of assessing serum proteins and cholesterol in malignancy. Cancer 35: 1223–1229, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corti MC, Guralnik JM, Salive ME, Harris T, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Havlik RJ: Clarifying the direct relation between total cholesterol levels and death from coronary heart disease in older persons. Ann Intern Med 126: 753–760, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weverling-Rijnsburger AW, Blauw GJ, Lagaay AM, Knook DL, Meinders AE, Westendorp RG: Total cholesterol and risk of mortality in the oldest old. Lancet 350: 1119–1123, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Block G, Horwich T, Fonarow GC: Reverse epidemiology of conventional cardiovascular risk factors in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 43: 1439–1444, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Ikizler TA, Block G, Avram MM, Kopple JD: Malnutrition-inflammation complex syndrome in dialysis patients: Causes and consequences. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 864–881, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tonbul HZ, Demir M, Altintepe L, Güney I, Yeter E, Türk S, Yeksan M, Yildiz A: Malnutrition-inflammation-atherosclerosis (MIA) syndrome components in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. Ren Fail 28: 287–294, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akdag I, Yilmaz Y, Kahvecioglu S, Bolca N, Ercan I, Ersoy A, Gullulu M: Clinical value of the malnutrition-inflammation-atherosclerosis syndrome for long-term prediction of cardiovascular mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease: A 5-year prospective study. Nephron Clin Pract 108: c99–c105, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, Emberson J, Wheeler DC, Tomson C, Wanner C, Krane V, Cass A, Craig J, Neal B, Jiang L, Hooi LS, Levin A, Agodoa L, Gaziano M, Kasiske B, Walker R, Massy ZA, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Krairittichai U, Ophascharoensuk V, Fellström B, Holdaas H, Tesar V, Wiecek A, Grobbee D, de Zeeuw D, Grönhagen-Riska C, Dasgupta T, Lewis D, Herrington W, Mafham M, Majoni W, Wallendszus K, Grimm R, Pedersen T, Tobert J, Armitage J, Baxter A, Bray C, Chen Y, Chen Z, Hill M, Knott C, Parish S, Simpson D, Sleight P, Young A, Collins R, SHARP Investigators : The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 377: 2181–2192, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ballantyne CM, Houri J, Notarbartolo A, Melani L, Lipka LJ, Suresh R, Sun S, LeBeaut AP, Sager PT, Veltri EP, Ezetimibe Study Group : Effect of ezetimibe coadministered with atorvastatin in 628 patients with primary hypercholesterolemia: A prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Circulation 107: 2409–2415, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villines TC, Stanek EJ, Devine PJ, Turco M, Miller M, Weissman NJ, Griffen L, Taylor AJ: The ARBITER 6-HALTS Trial (Arterial Biology for the Investigation of the Treatment Effects of Reducing Cholesterol 6-HDL and LDL Treatment Strategies in Atherosclerosis): Final results and the impact of medication adherence, dose, and treatment duration. J Am Coll Cardiol 55: 2721–2726, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kastelein JJ, Akdim F, Stroes ES, Zwinderman AH, Bots ML, Stalenhoef AF, Visseren FL, Sijbrands EJ, Trip MD, Stein EA, Gaudet D, Duivenvoorden R, Veltri EP, Marais AD, de Groot E, ENHANCE Investigators : Simvastatin with or without ezetimibe in familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 358: 1431–1443, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ridker PM, Cook N: Clinical usefulness of very high and very low levels of C-reactive protein across the full range of Framingham Risk Scores. Circulation 109: 1955–1959, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, Manolio TA, Burke GL, Wolfson SK, Jr, Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group : Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. N Engl J Med 340: 14–22, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polak JF, Pencina MJ, Pencina KM, O’Donnell CJ, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Sr: Carotid-wall intima-media thickness and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 365: 213–221, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lorenz MW, Markus HS, Bots ML, Rosvall M, Sitzer M: Prediction of clinical cardiovascular events with carotid intima-media thickness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 115: 459–467, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.