Summary

Background and objectives

There is a projected shortage of kidney specialists, and retention of trainees in nephrology is important. Determining factors that result in choosing a nephrology career could inform future strategies to attract nephrology fellows.

Design, settings, participants, & measurements

An anonymous, internet-based survey was sent to members of the American Society of Nephrology in June 2009. Respondents answered questions about demographics, training background, and career choices.

Results

Of the 3399 members, 913 (23%) returned the survey. Mean age was 51.1±10.5 years, and 46.1% were academic nephrologists. In addition, 38.4% of respondents graduated between 2000 and 2009. Interest in nephrology began early in training, with the intellectual aspects of nephrology, early mentoring, and participation in nephrology electives named as the most common reasons in choosing nephrology. Academic nephrologists were more likely to have participated in research in medical school, have a master’s degree or PhD, and successfully obtained research funding during training. Academic debt was higher among nonacademic nephrologists. Research opportunities and intellectual stimulation were the main factors for academic nephrologists when choosing their first postfellowship positions, whereas geographic location and work-life balance were foremost for nonacademic nephrologists.

Conclusions

These findings highlight the importance of exposing medical students and residents to nephrology early in their careers through involvement in research, electives, and positive mentoring. Further work is needed to develop and implement effective strategies, including increasing early exposure to nephrology in preclinical and clinical years, as well as encouraging participation in research, in order to attract future nephrology trainees.

Introduction

As a worldwide epidemic of CKD continues, there is a projected future shortage of nephrology specialists in the United States (1,2) despite an 11% increase in the number of nephrology trainees between 2005 and 2011 (3,4). Moreover, the number of US medical graduates who chose to pursue nephrology has fallen by 10% over this period (5). This shortfall has been taken up by international medical graduates, but the number of applicants from abroad also fell by 42% between 1996 and 2008, with residents citing financial issues, lifestyle, and the failure to stimulate an interest in nephrology during undergraduate training as factors contributing to a lack of interest in a career in nephrology (5). These concerns are not exclusive to adult nephrology in the United States but have also been reported both abroad (6,7) and in the field of pediatric nephrology (8). In addition, the recruitment and retention of trainees into academic nephrology is of significant concern.

Previous studies have reported low physician satisfaction with nephrology careers by established community nephrologists relative to other medical subspecialists, although the reasons for this dissatisfaction have not been further elucidated (9). In 2008, the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) founded the Task Force on Increasing Interest in Nephrology Careers to try to find ways to strengthen interest in a nephrology career among internal medicine residents (2). These efforts, however, would be strengthened and focused with additional information regarding the underlying reasons why trainees chose a career in nephrology, especially an academic nephrology track. A previous study reported that a decision to pursue a career in academic medicine includes the following factors: participation in a research-oriented training program, as well as strong research mentors and role models. Conversely, because this decision is often made early during medical residency, a heavy educational debt burden appears to be a significant disincentive to choosing an academic career (10).

To our knowledge, this study is the first career survey of practicing nephrologists in the United States. The goals were to elucidate the factors that most strongly influence trainees to choose a career in nephrology, and to assess overall satisfaction with career choices. We also sought to identify important factors in the choice of an academic nephrology track. By gathering these data, we hoped to inform future strategies to attract and retain nephrology trainees. We hypothesized that initial interest in nephrology occurs relatively early in medical training, that mentorship would be a highly important factor in the ultimate choice of a career in nephrology, and that early involvement in research would predict a future academic career.

Materials and Methods

An invitation email was sent to all active ASN members with an MD or equivalent degree (n=3933), containing a link to a web-based survey (see the Supplemental Appendix for the survey questions). Participants were informed that the survey would require an estimated 25 minutes to complete. Questions included demographics, training background, and career choices. Participation was anonymous and voluntary. The initial invitation email was sent in June 2009 and two follow-up reminders were sent after 1 and 3 weeks. The survey closed after 4 weeks.

The wording of the survey was approved by the ASN council after multiple revisions. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the University of Pennsylvania Office of Regulatory Affairs. It was determined that informed consent was not required.

For statistical analyses, most of these data were stratified by the self-reported status of respondents as having academic or nonacademic careers. Basic demographics were collected, including age, sex, race, current position, and years since completion of fellowship training. Career-specific questions included factors influencing career choice, prior research and funding, and career progression. Trends over time were examined by dividing respondents into cohorts according to when training was completed by approximate decade: before 1980, 1980–1989, 1990–1999, and 2000–2009. Comparisons between groups were made using the Pearson chi-squared test with a two-tailed P value <0.05 being considered significant.

Results

Demographics

The survey invitation was sent to 3933 active ASN members, 913 of whom completed the survey yielding a response rate of 23.2%. The mean age of respondents was 51.1±10.5 years and an average of 17.2±11.2 years had passed since completion of nephrology training. Relatively recent fellowship graduates comprised a substantial proportion of responders: 38.4% completed training between 2000 and 2009 and 19.5% between 2005 and 2009. The demographic characteristics of the responding nephrologists were stratified according to whether they had pursued a career in academic medicine and are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Academic Nephrologists (%) | Nonacademic Nephrologists (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 71.4 | 83.3 | <0.001 |

| Age, yr (SD) | 50.4 (10.6) | 50.8 (10.5) | 0.59 |

| Time since completion of training, yr (SD) | 17.2 (11.1) | 17.2 (11.3) | 0.95 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 71.9 | 61.2 | 0.10 |

| South Asian | 10.9 | 14.9 | |

| East Asian | 8.7 | 9.9 | |

| Hispanic | 3.3 | 6.2 | |

| African American | 2.7 | 3.3 | |

| Practicing in the United States | 95.7 | 98.4 | 0.03 |

| Board certification in internal medicine | 76.7 | 91.1 | <0.001 |

| Board certification in nephrology | 85.8 | 91.1 | 0.02 |

| Current salary ($) | |||

| <100,000 | 4.6 | 2.2 | 0.001 |

| 100,000–199,999 | 53.3 | 25.9 | |

| 200,000–299,999 | 34.9 | 38.1 | |

| 300,000–399,999 | 6.1 | 16.1 | |

| ≥400,000 | 3.4 | 15.3 | |

| Year of graduation from fellowship | Overall | ||

| 2005–2009 | 19.5 | ||

| 2000–2004 | 18.9 | ||

| 1990–1999 | 25.2 | ||

| 1980–1989 | 19.7 | ||

| Pre-1980 | 16.8 | ||

Although the majority of respondents were male, we observed a trend of an increasing proportion of women nephrologists by decade over the past 30 years. Among nephrologists who completed their training before 1980, 90% were male compared with just 66% of those who completed training between 2005 and 2009 (Figure 1). As seen in other medical subspecialties, Hispanics and African Americans remain under-represented in nephrology; 4.9% of respondents were Hispanic and 3.0% were African American, compared with 16.3% and 13% of the general population, respectively (11). Reflecting the pool of current entrants into nephrology training, 52.9% of recent graduates were Caucasian compared with 80.6% of those who graduated before 2000.

Figure 1.

Sex ratios among nephrology graduates over time. The number of practicing nephrologists who are women has been increasing steadily over the last 30 years, with the proportion increasing from 10% of pre-1980 graduates to almost 40% of the most recent graduating classes.

Education and Training

Table 2 summarizes the education and training characteristics of those surveyed. During medical school, 59% of respondents completed a renal elective (60.4% of recent graduate versus 58.2% of older graduates; P=0.54). Academic nephrologists were significantly more likely to have received research funding during their training and were also more likely to have completed an additional advanced degree with the proportion of trainees who have a master’s degree or a PhD has increased over the last 20 years. Interestingly, recent graduates were more likely to have received non–National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding during training. This may reflect the increasing proportion of graduates who are international medical graduates and are therefore potentially ineligible for traditional sources of funding. Nonacademic nephrologists had more debt at the end of their training. Similarly, debt levels were substantially higher among recent graduates even accounting for inflation, with 26.6% owing >$100,000 on completion of fellowship training and 19.5% owing >$150,000.

Table 2.

Training and education

| Academic Nephrologists (%) | Nonacademic Nephrologists (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renal elective in medical school | 62.2 | 55.4 | 0.05 |

| Medical degree | |||

| MD | 85.5 | 77.6 | <0.001 |

| Other (DO, MBBS, MBChB) | 14.5 | 22.4 | |

| Medical training in the US | 69.3 | 61.5 | 0.02 |

| Further qualifications | |||

| MD PhD | 7.5 | 1.3 | |

| Master’s degree | 22.0 | 11.8 | |

| PhD | 11.6 | 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Nephrology program type | |||

| Adult | 84.8 | 94.1 | <0.001 |

| Pediatric | 13.7 | 5.9 | |

| Training program location | |||

| Academic center | 93.8 | 84.3 | <0.001 |

| Academic-affiliated/community based | 5.5 | 12.2 | |

| Training program size (number of fellows) | |||

| 1–2 | 30.3 | 27.9 | 0.85 |

| 3–4 | 44.9 | 47.0 | |

| 4–5 | 17.1 | 16.5 | |

| ≥6 | 7.7 | 8.5 | |

| Training program length | |||

| 2-yr clinical | 30.6 | 63.6 | <0.001 |

| Clinical/research >2 yr | 59.4 | 29.9 | |

| Other | 10.0 | 6.5 | |

| Academic debt ($) | |||

| <25,000 | 65.6 | 64.8 | 0.01 |

| 25,000–100,000 | 24.5 | 17.6 | |

| >100,000 | 9.9 | 17.6 | |

| Research during training | |||

| Medical school | 59.6 | 40.4 | <0.001 |

| Residency | 48.7 | 38.2 | 0.07 |

| Fellowship | 96.7 | 88.7 | <0.001 |

| NIH funding during training | 22.9 | 10.6 | <0.001 |

| Non-NIH funding during training | 40.8 | 18.4 | <0.001 |

| NIH loan forgiveness | 6.2 | 1.8 | 0.001 |

NIH, National Institutes of Health.

Overall, 45% of respondents reported participating in research while in medical school, whereas 25% of academic nephrologists reported authoring a peer-reviewed paper during medical school compared with 17.3% of nonacademic nephrologists (P=0.01). Trainees who graduated between 2000 and 2009 were more likely to have participated in research during medical school.

Factors Influencing Career Choice

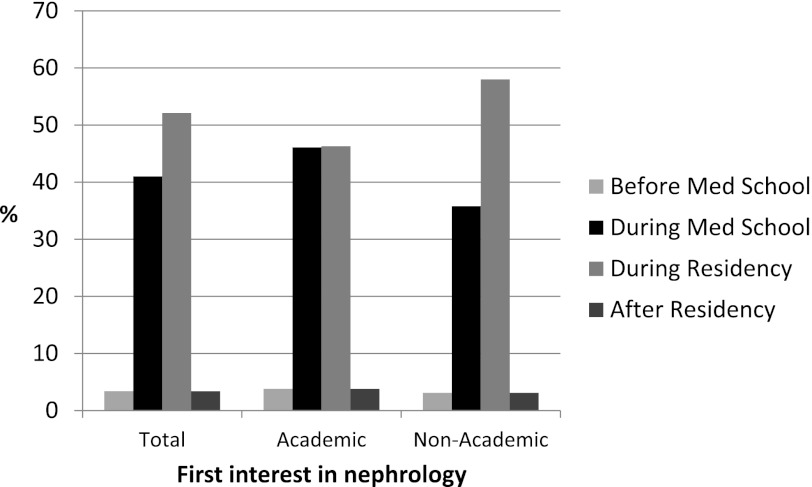

The final decision to pursue nephrology as a career was made by >70% of trainees during their residency. However, 44% of respondents reported that their initial interest in nephrology was kindled before or during medical school (Figure 2). Academic nephrologists were more likely to have become interested in nephrology earlier in their training as were more recent graduates.

Figure 2.

Initial interest in nephrology. Although overall, the majority of practicing nephrologists reported that their initial interest began in residency, more academic nephrologists reported developing an interest in nephrology before or during medical school (P=0.01).

One of the most important factors for choosing nephrology was an intellectual interest in the kidney, which was reported by 49% of respondents as the primary motivation. Furthermore, the importance of early mentoring was highlighted by the fact that 14% indicated that experience with a specific mentor during residency prompted them to choose nephrology, whereas 7.4% had reported that a relationship with a mentor during medical school was the strongest influence. Completing a residency rotation in nephrology was the most important factor for 9% of respondents. In a multivariate logistic regression model, the most important factors predicting a future career in academic nephrology were success in obtaining research funding during training (odds ratio [OR], 1.69; confidence interval [CI], 1.06–2.69), having a PhD (OR, 2.96; CI, 1.11–7.87) or a master’s degree (OR, 1.77; CI, 1.04–3.03), and completing an internal medicine residency in an academic medical center (OR, 3.05; CI, 1.85–5.05). The factors influencing career choice were not significantly different in those who graduated between 2000 and 2009 relative to those who graduated before then.

Current Position

Overall, 42.8% of respondents reported that they were still in their first job after training and 43.4% were currently working in an academic center. Of those presently at an academic institution, 46.7% were following a clinician-educator track, whereas 34.2% were on a physician-scientist track. Senior nephrologists appear to be over-represented in our sample, with 49.7% full professors and 27.8% division or department chiefs. For respondents currently in private practice, 66% were in single-specialty groups. More than half continued to be affiliated with a teaching hospital. Nephrologists in private practice reported spending a greater proportion of their time in direct patient care compared with academic nephrologists (75.7% versus 41.3%; P<0.001).

Table 3 lists the major factors determining why the respondents chose their initial and current positions. The availability of research opportunities was the most important factor for the majority of academic nephrologists. For nonacademic nephrologists, location, salary, and work-life balance took precedence for their initial choice of position.

Table 3.

Factors most important in choosing position

| Position | Factor | Academic Nephrologists (%) | Nonacademic Nephrologists (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| First position | Research opportunities | 31.3 | 10.8 |

| Intellectual stimulation | 11.0 | 5.7 | |

| Specific fellowship mentor | 10.4 | 7.6 | |

| Location | 10.4 | 22.7 | |

| Work-life balance | 7.6 | 16.0 | |

| Current position | Salary | 22.5 | 24.0 |

| Leadership opportunities | 19.1 | 4.6 | |

| Specific fellowship mentor | 11.0 | 5.3 | |

| Prestige | 9.3 | 17.7 | |

| Other career opportunities | 8.7 | 4.6 |

Career satisfaction results are summarized in Table 4. Overall, both academic and nonacademic nephrologists expressed high levels of satisfaction with their careers and very few respondents were unhappy that they chose nephrology as a career. Academic nephrologists were more likely to express dissatisfaction at their level of remuneration. Nonacademic nephrologists were more likely to feel that an academic career was incompatible with having a family and that there was too much pressure to publish. Recent graduates were more likely to say that they regretted their choice of nephrology as a career (13.9% versus 8.3%; P=0.02).

Table 4.

Career satisfaction

| Academic Nephrologists (% Agree or Strongly Agree) | Nonacademic Nephrologists (% Agree or Strongly Agree) | |

|---|---|---|

| Satisfied with my career trajectory | 84.0 | 79.4 |

| I have work-life balance | 66.9 | 62.7 |

| Satisfied with work environment | 78.3 | 72.4 |

| Satisfied with salary | 53.2 | 66.2 |

| Current job is stressful | 68.7 | 62.0 |

| Enjoy patient care | 93.2 | 93.3 |

| Intend to leave job next 12 mo | 12.7 | 15.0 |

| Perform at highest potential | 73.6 | 80.2 |

| Salary reflects achievements | 38.3 | 50.5 |

| Regret choosing nephrology | 6.7 | 18.4 |

| High degree of autonomy | 82.7 | 83.5 |

| Too much pressure to get grants/research/publications in academic medicine | 42.1 | 60.2 |

| Academic career compatible with having a family | 72.2 | 59.1 |

| Adequate administrative support | 40.4 | 55.2 |

| Working with chronic patients in nephrology is appealing | 73.7 | 71.9 |

| Wide variety of job opportunities for nephrologists | 75.7 | 61.8 |

Discussion

The population of patients with CKD is expanding and the current growth in the number of nephrologists is not sufficient (1,2). One key concern is the documented declining interest in nephrology among US medical graduates (5), with the proportion of international medical graduates in nephrology fellowship positions increasing from 41% to 56% in the past 5 years (3,4). Furthermore, despite the fact that >50% of medical school graduates are now female, nephrology training remains male dominated, although there has been a trend toward increased female participation in renal medicine over the past 10 years as previously reported (4) and observed in this study. The under-representation of minorities in nephrology fellowships is also of significant concern. African Americans comprise 13% of the US population and 32% of patients with ESRD and yet only 3.8% of nephrology trainees in 2008 were African American (12).

Efforts are being made to increase interest in a nephrology career among internal medicine residents through the establishment of an ASN Workforce Committee, which was initially established as the Task Force on Increasing Interest in Nephrology Careers. The committee has been collecting survey data to evaluate the level of interest and factors in subsequently choice of a career in nephrology among residents (2). Our survey data suggest that these efforts should be focused more on medical students. With the trend toward increasing subspecialization in medicine in general, there is a sense that trainees are being required to make career decisions earlier and positive experiences during medical school influence future decisions. Anecdotally, nephrology may suffer from the perception that the patients are sicker than other specialties with an element of hopelessness (5). This may be because exposure to renal patients in medical school is largely restricted to acute care of chronic dialysis patients with limited exposure to ambulatory care and transplantation (5).

Furthermore, medical students may feel that renal pathophysiology courses are too complex and uninteresting (5). One challenge may be to develop nephrology curricula that are broad and relevant while emphasizing the diversity of opportunities that exist in a nephrology career, including interventional nephrology, transplantation, recent advances in the understanding of the pathophysiology of renal disease, and improvements in the delivery of dialysis. Importantly, half of those surveyed reported that their primary reason for choosing nephrology was an intellectual interest in the subject. We must find ways to best channel this enthusiasm toward potential nephrology trainees. One potential approach would be to formally identify medical students with an interest in nephrology earlier in their training. Faculty with an interest in promoting nephrology careers could be encouraged to mentor these students and nephrology electives could be better structured to include a broad mix of inpatient and outpatient care, thus exposing students to the broad range of paths that exist within a nephrology career (13).

Previous studies have shown that factors such as the presence of research-oriented programs, mentors, previous involvement in research, and debt were important in predicting whether a trainee would pursue a career in academic medicine, and this was reflected in our survey (10). Academic debt is a growing problem and may be a significant disincentive to entry into a career in academic medicine in particular where salaries are generally lower. A small proportion of respondents received NIH loan forgiveness and consideration could be given to expanding this program. In the current political environment, it is unlikely that there will be a substantial increase in government funding of research; as a result, foundation and industry funding is increasingly important. This is particularly the case in nephrology, where the large number of non-US medical graduates is potentially excluded from many traditional forms of research funding. As a result, the proportion of foreign medical graduates who practice academic nephrology is lower than their US-trained colleagues. There may be a place for providing funding aimed specifically at these trainees to encourage their participation in research.

In other medical specialties, a growing number of academic physicians are in nontenure tracks with hospitalists making up a significant proportion of the total. There is disproportionate burnout in this group due in part to a lack of a clear path toward advancement (14). However, there is a trend toward diversifying the number of paths to tenured positions in academic medicine with the traditional model of a university professor who spends 80% of his or her time in research being joined by clinician educators and pure clinicians who provide valuable clinical, education, and revenue services to hospitals. This diversity of academic roles could be better adapted in the field of nephrology. Consequently, emphasizing the array of options to trainees early in their careers could help retain a higher proportion in academic medicine who may not otherwise have realized that there was a clear path to advancement outside the traditional model of majority research (15).

Formal training in research methodology is also important, and this has been shown to increase retention of trainees in clinical research careers (16). Nephrology joined the national resident matching program in 2009 and most programs now match applicants using this process. This has incentivized nephrology applicants to interview at a larger number of institutions and may allow for more appropriate placement of applicants on career paths that better fit their goals, ultimately leading to high rates of long-term retention of trainees in clinical and academic nephrology (17).

There are a number of important limitations to our study. Although the survey was sent to all active ASN members, relatively senior faculty members were over-represented and therefore it may not be representative of the entire membership. The group that is primarily of interest is the recent graduates because their experience would be most comparable with current trainees. In this study, 38% of respondents graduated between 2000 and 2009 and 19.5% graduated since 2005. There have been substantial changes both in the demographics of trainees entering nephrology and the overall structure of training programs (in part due to changes in work hours mandated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education). A recent paper examining the experience of trainees who graduated between 2005 and 2009, which primarily examined procedural and clinical competence, has provided important information about nephrology education as well (18). The primary focus of this study was to determine the factors that lead to a career in academic nephrology, and potential future directions for study include comparisons of training experiences and career trajectories of recent trainees with those of earlier graduates. Respondents were generally happy with their career choices and less satisfied members may not have been inclined to complete this study. The overall response rate of 23% would not be atypical for an online survey tool but there was almost certainly some nonresponse bias. The length of time required to complete the survey may have discouraged potential respondents. Unfortunately, the ASN does not have summary demographic data for the entire membership that would enable us to formally evaluate how different the respondents were compared with the overall group. Similarly, it is uncertain how representative the ASN membership is of nephrologists in general because all US-based nephrologists are not ASN members. Surveys were not complete for all respondents; as a result, there were some missing data that may have biased our results. Along with understanding why the respondents chose a nephrology career, it would also be useful to understand the reasons why internal medicine trainees do not choose nephrology, which we cannot assess with this study. This is a potential focus for further research.

In summary, this study provides an insight into the reasons why current ASN members chose to pursue a career in nephrology; as a result, these results can help inform efforts to increase interest in a nephrology career among future trainees. Our findings highlight the importance of early exposure to nephrology in medical school. Efforts should be focused at identifying potential trainees early in their training and providing positive mentoring at an early stage. Nephrology electives should be structured in such a way as to demonstrate the diversity of careers within nephrology and should not be limited to the traditional inpatient electives. In particular, interest in nephrology research should be encouraged in medical school and during residency through participation in formal research training. More generally, efforts need to be made to decrease the debt burden on US medical graduates, allowing them more opportunity to choose academic careers. Similarly, the lack of available research funding for non-US medical graduates should be addressed. This will ensure that the next generation of nephrology trainees is adequately prepared for the challenges of caring for the growing population of nephrology patients while continuing to advance the field of nephrology research.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the ASN for their support of this project. We also thank Dr. Judy Shea and Dr. Elizabeth O’Grady for execution of the web-based questionnaire, data management, and statistical analyses, as well as Tod Ibrahim and Susan Owens for their administrative support.

Funding was provided by the ASN.

Footnotes

G.M.M. and L.T. are co-first authors and contributed equally to this work.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.03250312/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Estimating workforce and training requirements for nephrologists through the year 2010. Ad Hoc Committee on Nephrology Manpower Needs. J Am Soc Nephrol 8[Suppl 9]: S9–13, i–xxii, 1–32 passim, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Parker MG, Ibrahim T, Shaffer R, Rosner MH, Molitoris BA: The future nephrology workforce: Will there be one? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1501–1506, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brotherton SE, Etzel SI: Graduate medical education, 2005-2006. JAMA 296: 1154–1169, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brotherton SE, Etzel SI: Graduate medical education, 2010-2011. JAMA 306: 1015–1030, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehrotra R, Shaffer RN, Molitoris BA: Implications of a nephrology workforce shortage for dialysis patient care. Semin Dial 24: 275–277, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lane CA, Brown MA: Nephrology: A specialty in need of resuscitation? Kidney Int 76: 594–596, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lane CA, Healy C, Ho MT, Pearson SA, Brown MA: How to attract a nephrology trainee: Quantitative questionnaire results. Nephrology (Carlton) 13: 116–123, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinstein AR, Reidy K, Norwood VF, Mahan JD: Factors influencing pediatric nephrology trainee entry into the workforce. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1770–1774, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leigh JP, Tancredi DJ, Kravitz RL: Physician career satisfaction within specialties. BMC Health Serv Res 9: 166, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borges NJ, Navarro AM, Grover A, Hoban JD: How, when, and why do physicians choose careers in academic medicine? A literature review. Acad Med 85: 680–686, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Census Bureau: State and County QuickFacts. Available at: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html Accessed August 16, 2012

- 12.Onumah C, Kimmel PL, Rosenberg ME: Race disparities in U.S. nephrology fellowship training. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 390–394, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jhaveri KD, Shah HH, Mattana J: Enhancing interest in nephrology careers during medical residency. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 350–353, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glasheen JJ, Misky GJ, Reid MB, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A: Career satisfaction and burnout in academic hospital medicine. Arch Intern Med 171: 782–785, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman MM, Richard GV: Faculty career tracks at U.S. medical schools. Acad Med 86: 932–937, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapoor K, Wu BU, Banks PA: The value of formal clinical research training in initiating a career as a clinical investigator. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 7: 810–813, 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohan DE, Rosenberg ME: Nephrology training programs and applicants: A very good match. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 242–247, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berns JS: A survey-based evaluation of self-perceived competency after nephrology fellowship training. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 490–496, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.