Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

The objectives of this study were to verify the degree of anxiety, respiratory distress, and health-related quality of life in a group of asthmatic patients who have experienced previous panic attacks. Additionally, we evaluated if a respiratory physiotherapy program (breathing retraining) improved both asthma and panic disorder symptoms, resulting in an improvement in the health-related quality of life of asthmatics.

METHODS:

Asthmatic individuals were assigned to a chest physiotherapy group that included a breathing retraining program held once a week for three months or a paired control group that included a Subtle Touch program. All patients were assessed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV, the Sheehan Anxiety Scale, the Quality of Life Questionnaire, and spirometry parameter measurements.

RESULTS:

Both groups had high marks for panic disorder and agoraphobia, which limited their quality of life. The Breathing Retraining Group program improved the clinical control of asthma, reduced panic symptoms and agoraphobia, decreased patient scores on the Sheehan Anxiety Scale, and improved their quality of life. Spirometry parameters were unchanged.

CONCLUSION:

Breathing retraining improves the clinical control of asthma and anxiety symptoms and the health-related quality of life in asthmatic patients.

Keywords: Asthma, Physiotherapy, Panic, Breathing Retraining, Anxiety

INTRODUCTION

The relationship between asthma and anxiety is well-established. Symptoms, such as respiratory discomfort, are highly common in both panic disorder and in asthma. There is evidence that breathing retraining helps to control the symptoms of asthma and panic attacks with consequent improvement in an asthmatic's quality of life (1)-(3). However, there is no strong evidence that a Chest Physiotherapy (CPT) program, specifically the breathing retraining technique, helps to reduce the symptoms of anxiety and improve asthma control (1).

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways in which many different types of cellular elements play roles. In susceptible individuals, this inflammation causes recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness and coughing (4). There is increasing recognition that psychological factors influence the onset and course of asthma. Furthermore, there is a significant correlation between asthma and negative emotions, particularly anxiety and depression (2).

Anxiety is a very common illness, with a prevalence estimated at up to 20% of the adult population. Anxiety has demonstrated effects on indicators of quality of life (5). Panic disorder and agoraphobia are among the many anxiety disorders. Agoraphobia is the intense fear of finding oneself in crowded places where there may be a perception of difficulty to escape.

Previous cross-sectional community-based studies have provided evidence for a relatively specific association between the prevalence of asthma and panic disorder (2),(6). Both anxiety and depression are known to influence the quality of life in asthmatics, and both put stress on the health care system (3). A previous longitudinal study showed that asthma increases the risk of panic, anxiety, and depression (6). More complex models have described asthma as an organic disease that is highly vulnerable to psychological influences (7),(8). Mood disorders were identified in 53% of asthmatic patients and in 34.9% of non-asthmatics (9).

According to the 2009 Physiotherapy Guidelines (12), breathing retraining (as part of CPT) incorporates a reduction in the respiratory rate and/or tidal volume with relaxation training, which helps to control the symptoms of asthma and is recommended as level 1++ scientific evidence (Grades A and B). Breathing retraining includes instruction in pursed-lip breathing and coordinated breathing with respiratory exercises and has the added benefit of reducing anxiety and stress (13).

Physiotherapists have advocated chest physiotherapy for the management of breathing disorders (13),(14). In a cohort of asthmatics, a randomized controlled trial of breathing retraining and relaxation led to a significant reduction in respiratory symptoms and improvement in quality of life (15). In another randomized controlled trial, asthmatic patients trained in diaphragmatic breathing had clinically relevant improvements in their quality of life, even nine months after the intervention (16). Other studies (17),(18) reported effective reductions in the number of symptoms, the frequency of attacks and degrees of depression and anxiety, and improvements in respiratory parameters.

This study aimed to assess the degree of anxiety and respiratory distress and the quality of life in a group of asthmatic patients who have previously experienced panic attacks. We also demonstrated that a respiratory physiotherapy program (breathing retraining) may improve both asthma and panic disorder symptoms, resulting in an improvement in the health-related quality of life of asthmatics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and eligibility

In this prospective study, we used specific and validated methods for the quantification of anxiety symptoms in two randomly selected samples of asthmatic patients from the Asthma Clinic of the Pneumology Department of the Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade de São Paulo. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the institution, and informed written consent was obtained from each patient. Asthmatic patients who had well-controlled symptoms and received regular inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting bronchodilators for at least one month were included in the study according to the criteria of the Global Initiative for Asthma (2). The inclusion criteria for the study were: 1. at least three symptoms of panic and agoraphobia; 2. persistent fear of public places or open areas or the need to be removed from fear situations that trigger the crisis; and 3. fulfillment of the criteria of asthma according to American Thoracic Society (ATS).

All patients underwent a clinical exam and were evaluated with the DSM-IV-R to establish panic and agoraphobia symptoms, the Sheehan Anxiety Scale, the Quality of Life questionnaire, forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced expiratory flow 25-75% (FEF 25-75%), and FEV1/FVC ratio (FEV1/FVC). Patients were evaluated at the beginning of the study (Table 1 and Table 2) and twelve weeks later [twice during the study (T = 0 and T = 12)].

Table 1.

Preliminary patient demographic and spirometry data for both the Breathing Retraining Group (BRG) and the Subtle Touches group (STG). Eighty percent of the BRG patients and 72.2% of the STG patients had moderate/severe asthma. The BRG patients had a higher frequency of previous smoking. Both groups had high scores for panic disorder and agoraphobia, as indicated by the appropriate scales. The BRG and the STG had the same Daily Symptom Diary median scores. Subject characteristics

| Physiotherapy (BRG) N = 20 | Control (STG) N = 18 | |

| Age, yr, | ||

| Mean±SD | 44.5 ±11.5 | 41.5±12.1 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 03 | 03 |

| Female | 17 | 15 |

| FEV1 % predicted | 68.8±21.5 | 66.5±22.0 |

| Mild asthma | 20% (04/20) | 27.8% (05/18) |

| Moderate asthma | 50% (10/20) | 50% (09/18) |

| Severe asthma | 30% (06/20) | 22.2% (04/18) |

| Current smoker | 0 | 0 |

| Past smoker | 15% (3/20) | 5.5% (1/18) |

| PD*) | 5.00 (4.00 – 6.00) | 4.00 (3.00 – 4.00) |

| Sheehan | 0.20±0.16 | 0.27±0.16 |

| AG** | 4.00 (3.00 – 4.00) | 3.00 (3.00 – 4.00) |

| DSS*** | 10.90±6.30 | 10.90±6.30 |

PD = Panic disorder (median). ** AG = Agoraphobia (median). *** DSS = Daily Symptom Scale (median)

Table 2.

The evolution of parameters expressed as median values (25%-75%). At the start of the study, both groups presented with equally compromised health-related quality of life scores and the same levels of panic and asthma symptoms. Final measurements indicated improvements in all domains.Variations in the domains of quality of life and symptoms in asthmatic patients.

| Group | Physiotherapy (BRG) (Before) Median [25%-75%] | Physiotherapy (BRG) (After) Median [25%-75%] | Control (STG) (Before) Median [25%-75%] | Control (STG) (After) Median [25%-75%] | p-value |

| VDAT | 66.0 [99.8-48.9] | 99.9 [99.9-4.1] | 84.0 [99.8-48.6] | 83.9 [99.8-66.0] | *0.05 |

| VDSF | 6.7 [7.8-5.4] | 3.7 [6.0-3.4] | 6.6 [7.6-3.8] | 4.5 [6.5-3.2] | *0.012 |

| VDPL | 48.5 [52.0- 30.6] | 18.0 [26.9-10.4] | 49.6 [58.0-30.9] | 26.3 [36.3-12.3] | *0.001 |

| VDP | 36.0 [54.2-24.6] | 54.9 [73.8-36.0] | 35.9 [49.0-25.0] | 48.9[62.0-36.0] | *0.01 |

| VDSE | 49.9 [66.0-37.0] | 75.3 [82.9-51.0] | 49.9 [66.0-49.9] | 49.7 [82.7-49.7] | *0.01 |

| PD | 5.0 [6.0-4.2] | 3.7 [5.0-1.1] | 4.0 [4.0-3.2] | 3.7 [4.0-3.0] | *0.027 |

VDAT - Variation of the domain: adherence to treatment between groups; VDSF - Variation of the domain: severity/frequency between groups; VDPL - Variation of the domain: physical limitation; VDP - Variation of the domain: psychosocial; VDSE - Variation of the domain: social-economic; VRS - range of symptoms; PD - panic disorder. * Comparing the beginning of the experiments to the end of the protocol.

Patients recorded daily symptoms/signs and rescue salbutamol use in their diaries. The peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) was monitored with a portable device (Mini – Wright, Clement Clark International, Harlow, Essex, England) once a week for three months. Patient diaries detailing symptoms and rescue salbutamol use were collected at three months.

The Sheehan Disability Scale (19) is a three-item self-reported scale that measures the severity of the disability in the areas of work and family life, home responsibilities, and social activities or hobbies. Each of these three areas is scored on a Likert scale of ten points (a score of 0 is “not at all impaired,” 5 is “moderately impaired” and 10 is “very severely impaired”). The scale provides a measurement of total functional disability (range 0-30) and has been shown to have appropriate internal reliability and validity (20). It has previously been used in studies of panic disorder (21).

The Quality of Life questionnaire assesses an individual's well-being, complements traditional health and clinical measures, and captures the wider impact that asthma has on physical, psychological, and social life. The specific instrument we used for the determination of quality of life has been validated for use in clinical trials (22). It assesses four domains: activity limitation, symptoms, emotional function, and environmental stimuli (22). The Quality of Life questionnaire assesses physical limitation, the severity and frequency of symptoms, adherence to treatment, and psychological factors.

Experimental groups

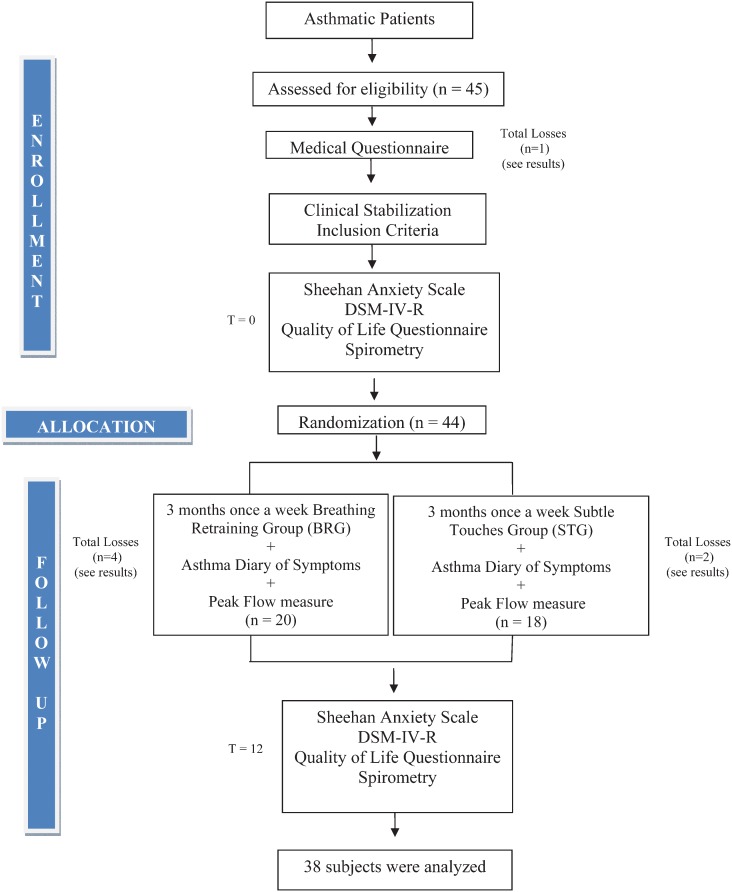

Thirty-eight asthmatic patients with a history of panic symptoms entered this case-controlled study and were randomly assigned (1:1 for two groups) to a breathing retraining group (BRG, n = 20) or a control group that received Subtle Touch (STG) (n = 18). The Subtle Touch technique controls for the presence and the action of the physiotherapist as potential confounding factors (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design.

Exercise protocol

The same physiotherapist performed all of the physical therapy maneuvers. The subjects were seen individually, once a week, in an outpatient setting in which each patient underwent a total of 30 minutes of Subtle Touch or breathing retraining.

Breathing retraining consists of six repetitions of each the following physiotherapeutic exercises: 1. pursed-lip breathing associated with a lying relaxed posture; 2. manual expiratory passive therapy maneuvers; 3. diaphragmatic breathing; 4. hiccup inspiratory maneuvers; 5. postural orientation; and 6. twenty repetitions of Pompage (maneuvers performed for the muscle fascia).

Subtle Touch, also called Calatonia, is a Jungian method (23) that was developed by Petho Sandor, who demonstrated that continued treatment with Subtle Touch promotes the reduction of anxiety and depression and leads to a stable mood. In this study, we used only the physical aspects of Subtle Touch. This technique uses both hands simultaneously on both sides of the thorax. The Subtle Touch technique is performed in three steps: 1. a gentle pressure is imposed on the skin with hands or fingertips for three breaths, with a slow decompression after the last one; 2. soft touches are performed during the next three breaths; and 3. hands or fingertips maintain only slight contact with the skin and remain still for three more respiratory cycles.

Due to the limited sample size, a confidence interval of 95% and a maximum estimate error of 20% were used. A control group (STG) was used to reduce sample limitations.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Sigma Stat software (Jandel Corp, San Rafael, CA). The data are presented as means and standard deviations (SD) for age, FEV1, and the Daily Symptom Scale. The scores for panic disorder (PD), agoraphobia (AG), and Sheehan's Disability Scale are expressed as medians and ranges. The distribution of asthma severity and the frequency of smoking are expressed as percentages. All data were analyzed intra-group and inter-group and were compared to the values at the beginning and end of the study. A paired Student's t-test was used to compare the initial and final intra-group values. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare the experimental groups before and after experimental exercise. Values of beta-2 agonist use, spirometry parameters and peak flow were compared using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the clinical and demographic data of 38 patients who completed the study. Forty-five patients were initially recruited. Seven patients did not complete the study; one died before randomization. Of the six remaining patients who did not complete the study, four were in the BRG. Three of these four patients did not attend all the physiotherapy sessions, and one suffered an asthma exacerbation. Two patients in the STG did not complete the study. One of these two patients suffered an asthma exacerbation, and the second patient did not attend all the scheduled sessions (Figure 1).

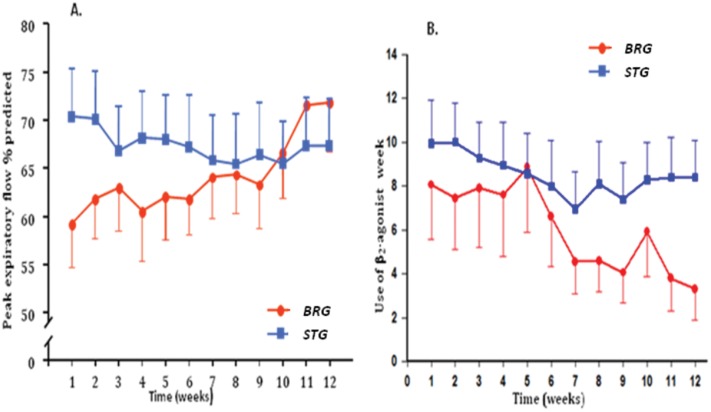

The spirometry data from the beginning of the trial revealed that, in both groups, the patients had values indicative of moderate or severe asthma (Table 1). There were no significant differences in spirometry measurements (FVC, FEV1, FEF25-75%, FEV1/FVC) between the two groups throughout the study. Interestingly, the peak flow rate was significantly different between both groups.

We observed a progressive and significant increase in the peak flow rate in the BRG (p≤0.05); it remained stable with a slight downward trend in the STG (Figure 3A). The use of a β2 agonist (salbutamol) as a relief medication (Figure 3B) decreased over time after the sixth week of the study, which was significant for the BRG (p≤0.05).

Figure 3.

Weekly peak flow rate measurements (3A) and daily use of β2 agonist (3B) were monitored over three months. Peak flow rate progressively and significantly increased in the BRG (p<0.05) but remained stable in the STG (Figure 3A). In the BRG, the use of β2 agonist (salbutamol) as a relief medication (Figure 3B) decreased over time, particularly after the sixth week (p<0.05).

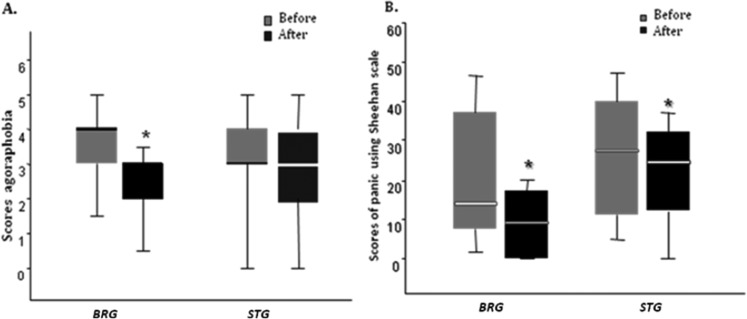

Patients from both groups had high levels of agoraphobia and panic disorder at the start of the study. Statistically significant reductions in panic disorder symptoms (according to the DSM-IV-R) (p≤0.05) and agoraphobia (p≤0.05) were observed only in the BRG (Figure 2A). There was no difference in the same parameters when multiple analyses were performed comparing the BRG with the STG. Panic scores, according to the Sheehan scale, exhibited significant decreases for both the BRG and the STG (p≤0.05) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

At the end of the study, the scores for agoraphobia and panic disorder symptoms (Figure 2A) were significantly reduced only in the BRG group (p<0.05). According to the Sheehan scale, panic scores (Figure 2B), were significantly decreased for both the BRG and the STG (p<0.05). There were no differences in the same parameters when multiple analyses were performed comparing the BRG with the STG.

Initially, the asthmatic patients who participated in this study had substantial limitations in their quality of life, despite receiving notably good clinical treatment and being considered stable. The variability in the Quality of Life questionnaire occurred throughout the four domains (Table 2). Over the course of multiple analyses, there were statistically significant decreases in the values for the “physical limitation” domain (p≤0.05) and the “gravity/frequency” domain (p≤0.05). There was also an improvement in the psycho-social factors domain for the two groups, although this improvement was not statistically significant (p<0.01). At the end of the protocol, only the BRG showed significant differences in the “adherence to treatment” (p≤0.05) and “social economic” (p≤0.05) domains.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the three-month chest physiotherapy program improved the clinical control of asthma and the quality of life and decreased the symptoms of panic and agoraphobia in a group of asthmatics with high anxiety scores at baseline. Spirometry parameters remained unchanged, the daily peak flow values increased and consumption of salbutamol decreased. The Subtle Touch technique also led to improvements in these parameters, but not to the same extent as breathing retraining.

Subjectively, the authors noted in their clinical experience that episodes of breathlessness caused quality of life changes in asthmatics, including a high attention deficit and a sense of hopelessness regarding their disease prognosis. Additionally, patients could learn about conscious control over breathing to overcome psychological aspects. A review of the literature and some existing publications on chest physiotherapy, anxiety, and asthma revealed that there was a theoretical basis for a more organized treatment approach.

Patients enrolled in this study had symptoms of asthma for more than twenty years; 76.3% had histories of hospitalization during these years, and 34.2% had been in an intensive care unit. All of the patients had high scores for panic and agoraphobia. As was observed by other authors, these data suggest that asthma severity can be associated with anxiety and vice versa (24).

Some authors have sought to understand and clarify the relationships between the respiratory system, mental state, and personality (25),(26). There are many reports and studies linking anxiety disorders and depression to respiratory dysfunction (5),(26),(27) and respiratory disorders in anxious patients without lung disease (2),(16).

A high level of psychiatric comorbidities was shown in patients with severe asthma or difficult-to-control asthma (28). Panic and fear are established risk factors for worse asthma-related morbidity, independent of objective measures of pulmonary function (29). Generalized panic or fear may affect the self-management of asthma by influencing decisions about the use of rescue medication and the avoidance of activities. The general tendency to respond with anxiety to perceived threats in the environment (trait anxiety) might lead patients to treat their emotional distress with short-acting β2-agonists, particularly if they confuse respiratory symptoms of anxiety for asthma (30). However, excessive use of short-acting β2-agonists might also contribute to greater levels of anxiety because of the side-effects of these medications, such as tachycardia and tremor (31),(32). The association between generalized panic or fear and avoidance of activities due to asthma may reflect agoraphobic anticipation and may extend well beyond adaptive aversion to asthma triggers (33).

This behavior may manifest as a greater demand for health care, higher numbers of missed work and school days, and increased morbidity and mortality rates. This behavior can also result in the unnecessary use of medications.

There are few reports that use chest physiotherapy and relaxation techniques to control respiratory disease and anxiety in asthmatics. The relationship between respiratory and psychological disorders remains unclear.

A systematic review concluded that chest physiotherapy may have some potential benefits (34). Two separate randomized controlled trials of patients with asthma demonstrated that chest physiotherapy and relaxation significantly improved health-related quality of life and identified significant reductions in asthma symptoms (15),(35). These results also call for further studies to demonstrate the efficacy of breathing retraining on asthma (36). In accordance with the literature, these new concepts in asthma management should help reduce hospitalizations and emergency room visits, increase adherence to treatment and improve patient quality of life (37).

This study focused on non-pharmacological interventions in addition to the recommended drug treatment for controlling asthma. A breathing retraining program led to a statistically significant effect in controlling symptoms of anxiety and airway obstruction, with improvements in peak flow rate and the use of lower amounts of salbutamol without significant changes in the FEV1 of both groups. The peak flow rate depends on the patient's effort and the strength and speed of expiratory muscle contraction. Breathing retraining promotes biomechanical reorganization and improves muscle function, which leads to a significant improvement in peak flow independent of an improvement in airway obstruction (22).

A control group (Subtle Touch) was introduced to reduce possible confounding variables, such as the impact of a therapist and the weekly contact with patients during visits. Even in the Subtle Touch group, a generalized significant improvement was observed. Subtle Touch treatment reduced scores for panic disorder and agoraphobia, although to a lesser degree than in the breathing retraining group. Assuming that all patients were under optimal drug therapy, the superior outcome observed for the BRG compared to the STG is evidence for the benefits of breathing retraining to control asthma and anxiety symptoms.

For the first time, we have demonstrated that the Subtle Touch technique reduces the psychiatric symptoms associated with asthma. These results are consistent with the hypothesis by Sandor. Subtle Touch is a deep relaxation technique that leads to the regulation of muscle tone and the promotion of physical and psychological rebalancing of the patient. Essentially, Subtle Touch therapy is performed by applying gentle stimuli in areas of the body where there are particularly high concentrations of nerve receptors. By promoting muscle relaxation, such techniques may lead to improvements in respiratory muscle function. According to the Jungian proposal, the Subtle Touch technique works by reducing anxiety.

This study noted an increase in peak flow values and a decrease in consumption of salbutamol for patients who underwent physiotherapy. These results are consistent with those of other studies (17) that show an effective reduction of symptoms, frequency of attacks, and degree of depression and anxiety with physical therapy. The benefits observed in the twelve weeks of this study required observation for a longer period of time and were consistent.

In conclusion, breathing retraining improves the clinical control of asthma symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and the health-related quality of life in asthmatics. In particular, substantial benefits were observed in severely compromised patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the following Brazilian scientific agencies: FAPESP, CNPq, PRONEX-MCT, and FFM.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.GINA. Global Initiative for Asthma Report. 1995. Workshop Report Revision 2006. Updated 2007. 1995. Available from: www.ginasthma.com.

- 2.Goodwin RD, Pine DS. Respiratory disease and panic attacks among adults in the United States. Chest. 2002;122(2):645–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.2.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kullowatz A, Kanniess F, Dahme B, Magnussen H, Ritz T. Association of depression and anxiety with health care use and quality of life in asthma patients. Respir Med. 2007;101(3):638–44. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Upton MN, Ferrell C, Bidwell C, McConnachie A, Goodfellow J, Davey Smith G, et al. Improving the quality of spirometry in an epidemiological study: The Renfrew-Paisley (Midspan) family study. Public Health. 2000;114(5):353–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendlowicz MV, Stein MB. Quality of life in individuals with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):669–82. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodwin RD, Eaton WW. Asthma and the risk of panic attacks among adults in the community. Psychol Med. 2003;33(5):879–85. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright RJ, Rodriguez M, Cohen S. Review of psychosocial stress and asthma: an integrated biopsychosocial approach. Thorax. 1998;53(12):1066–74. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.12.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Opolski M, Wilson I. Asthma and depression: a pragmatic review of the literature and recommendations for future research. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2005;1:18. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yilmaz A, Cumurcu BE, Tasliyurt T, Sahan AG, Ustun Y, Etikan I. Role of psychiatric disorders and irritable bowel syndrome in asthma patients. Clinics. 2011;66(4):591–7. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000400012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cengage G.Chest Physical Therapy Longe JL, editor. Encyclopedia of Medicine 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 11. NIH NIOH Critical Care Therapy and Respiratory Care Section Department CcM , editor. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bott J, Blumenthal S, Buxton M, Ellum S, Falconer C, Garrod R, et al. Guidelines for the physiotherapy management of the adult, medical, spontaneously breathing patient. Thorax. 2009;64(Suppl 1):i1–51. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.110726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Innocenti DM. Chest conditions. Physiotherapy. 1969;55(5):181–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lum LC. Hyperventilation syndromes in medicine and psychiatry: a review. J R Soc Med. 1987;80(4):229–31. doi: 10.1177/014107688708000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holloway EA, West RJ. Integrated breathing and relaxation training (the Papworth method) for adults with asthma in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2007;62(12):1039–42. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.076430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas M, McKinley RK, Freeman E, Foy C, Prodger P, Price D. Breathing retraining for dysfunctional breathing in asthma: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2003;58(2):110–5. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.2.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kraft AR, Hoogduin CA. The hyperventilation syndrome. A pilot study on the effectiveness of treatment. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;145:538–42. doi: 10.1192/bjp.145.5.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grossman P, de Swart JC, Defares PB. A controlled study of a breathing therapy for treatment of hyperventilation syndrome J Psychosom Res. 1985;29(1):49–58. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sartorius N.Anxiety: A Psychobiological and Clinical Perspectives Sartorius NAV, Cassano G, Eisenberg L, Kielholz P, Pancheri P, Racagni G, editor. Washington, DC: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leon AC, Shear MK, Portera L, Klerman GL. Assessing impairment in patients with panic disorder: the Sheehan Disability Scale. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1992;27(2):78–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00788510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klerman GL. The current age of youthful melancholia. Evidence for increase in depression among adolescents and young adults. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:4–14. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliveira MA, Fernandes AL, Santos LA, Carvalho MA, Faresin SM, Santoro IL. Discriminative aspects of SF-36 and QQL-EPM related to asthma control. J Asthma. 2007;44(5):407–10. doi: 10.1080/02770900701364320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribeiro AJ, Gonçalves MI, Pereira MA, Rios AMG. A Subtle Touch, Calatonia and other somatic interventions with children and adolescents USABP Journal. 2007;6:33–47. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper CL, Parry GD, Saul C, Morice AH, Hutchcroft BJ, Moore J, et al. Anxiety and panic fear in adults with asthma: prevalence in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bolton MB, Tilley BC, Kuder J, Reeves T, Schultz LR. The cost and effectiveness of an education program for adults who have asthma. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6(5):401–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02598160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendes FA, Gonçalves RC, Nunes MP, Saraiva-Romanholo BM, Cukier A, Stelmach R, et al. Effects of aerobic training on psychosocial morbidity and symptoms in patients with asthma: a randomized clinical trial. Chest. 2010;138(2):331–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porzelius J, Vest M, Nochomovitz M. Respiratory function, cognitions, and panic in chronic obstructive pulmonary patients. Behav Res Ther. 1992;30(1):75–7. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(92)90101-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heaney LG, Conway E, Kelly C, Gamble J. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in a difficult asthma population: relationship to asthma outcome. Respir Med. 2005;99(9):1152–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dirks JF, Fross KH, Evans NW. Panic-fear in asthma: generalized personality trait vs. specific situational state. J Asthma Res. 1977;14(4):161–7. doi: 10.3109/02770907709104335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feldman JM, Siddique MI, Morales E, Kaminski B, Lu SE, Lehrer PM. Psychiatric disorders and asthma outcomes among high-risk inner-city patients. Psychosom Med. 2005. 2005;67(6):989–96. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188556.97979.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cazzola M, Matera MG, Donner CF. Inhaled beta2-adrenoceptor agonists: cardiovascular safety in patients with obstructive lung disease. Drugs. 2005;65(12):1595–610. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565120-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scalabrin DM, Solé D, Naspitz CK. Efficacy and side effects of beta 2-agonists by inhaled route in acute asthma in children: comparison of salbutamol, terbutaline, and fenoterol. J Asthma. 1996;33(6):407–15. doi: 10.3109/02770909609068185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yellowlees PM, Kalucy RS. Psychobiological aspects of asthma and the consequent research implications. Chest. 1990;97(3):628–34. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.3.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ernst E. Breathing techniques–adjunctive treatment modalities for asthma? A systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2000;15(5):969–72. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00.15596900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cowie RL, Conley DP, Underwood MF, Reader PG. A randomised controlled trial of the Buteyko technique as an adjunct to conventional management of asthma. Respir Med. 2008;102(5):726–32. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holloway E, Ram FS. Breathing exercises for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):CD001277. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001277.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cooper CL, Parry GD, Saul C, Morice AH, Hutchcroft BJ, Moore J, et al. Anxiety and panic fear in adults with asthma: prevalence in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]