Abstract

Protoplasts isolated from red-light-adapted Arabidopsis hypocotyls and incubated under red light exhibited rapid and transient shrinking within a period of 20 min in response to a blue-light pulse and following the onset of continuous blue light. Long-persisting shrinkage was also observed during continuous stimulation. Protoplasts from a hy4 mutant and the phytochrome-deficient phyA/phyB double mutant of Arabidopsis showed little response, whereas those from phyA and phyB mutants showed a partial response. It is concluded that the shrinking response itself is mediated by the HY4 gene product, cryptochrome 1, whereas the blue-light responsiveness is strictly controlled by phytochromes A and B, with a greater contribution by phytochrome B. It is shown further that the far-red-absorbing form of phytochrome (Pfr) was not required during or after, but was required before blue-light perception. Furthermore, a component that directly determines the blue-light responsiveness was generated by Pfr after a lag of 15 min over a 15-min period and decayed with similar kinetics after removal of Pfr by far-red light. The anion-channel blocker 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)-benzoic acid prevented the shrinking response. This result, together with those in the literature and the kinetic features of shrinking, suggests that anion channels are activated first, and outward-rectifying cation channels are subsequently activated, resulting in continued net effluxes of Cl− and K+. The postshrinking volume recovery is achieved by K+ and Cl− influxes, with contribution by the proton motive force. External Ca2+ has no role in shrinking and the recovery. The gradual swelling of protoplasts that prevails under background red light is shown to be a phytochrome-mediated response in which phytochrome A contributes more than phytochrome B.

Arabidopsis has been extensively used in genetic and molecular studies of photomorphogenetic responses. Although the major focus of these studies has been on the responses mediated by phytochrome (for review, see Whitelam and Devlin, 1997), it is also becoming a promising material in studies of blue-light-sensitive responses.

Inhibition of plant growth by blue light is a well-studied example of a blue-light-sensitive response (Cosgrove, 1994). Recent analyses of the hy4 mutant of Arabidopsis, which is impaired in blue-light-dependent inhibition of hypocotyl growth (Koorneef et al., 1980), have led to the discovery of the photoreceptor CRY1 (Ahmad and Cashmore, 1993; Lin et al., 1995a, 1995b). In Arabidopsis hypocotyls, Cho and Spalding (1996) were able to identify the blue-light-induced plasma membrane depolarization originally found in cucumber hypocotyls (Spalding and Cosgrove, 1989, 1992) and to demonstrate that plasma membrane anion channels are activated by blue light. Showing further that the responses in membrane potential and growth are inhibited by the anion-channel blocker NPPB, these authors concluded that the activation of anion channels contributes to the depolarization response and is a primary reaction involved in blue-light-dependent growth inhibition.

We found that the protoplasts isolated from maize coleoptiles shrink transiently in response to a pulse of blue light as well as to continuous blue light (Wang and Iino, 1997). This protoplast response is suggested to be causally related to the transient growth inhibition induced by blue light in maize coleoptiles. The present study investigated the possible occurrence of a protoplast shrinking response in Arabidopsis. We found that protoplasts from Arabidopsis hypocotyls shrink in response to blue light and extended the study to clarify its contribution to CRY1-mediated growth inhibition and to characterize the ion relationships involved.

In blue-light-dependent phototropism, the sensitivity and responsiveness to blue light are controlled by phytochrome (Liu and Iino, 1996a, 1996b; for earlier references, see Iino, 1990). The use of the phytochrome-deficient Arabidopsis mutants phyA, phyB, and phyAphyB has demonstrated that phototropic responsiveness of hypocotyls is tightly controlled by phytochrome (Hangarter, 1997; Janoudi et al., 1997; Liu and Iino, 1997). Recent studies with such Arabidopsis mutants have indicated that phytochrome is also necessary for full expression of CRY1-mediated growth inhibition (Casal and Boccalandro, 1995; Ahmad and Cashmore, 1997). In the present study we used phyA, phyB, and phyAphyB mutants to investigate possible links between phytochrome and blue-light-induced protoplast shrinking.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

The wild type and mutants of Arabidopsis used in the present study were in the Landsberg erecta background. Seeds of wild-type Arabidopsis and the mutant hy4–1 (Koorneef et al., 1980) were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Ohio State University, Columbus). Seeds of the mutants phyA-201 (Nagatani et al., 1993) and phyB-5 (Koorneef et al., 1980) and the double mutant phyA-201/phyB-5 (Reed et al., 1994) were provided by Dr. Nagatani (Tokyo University, Japan). These seeds were multiplied in our greenhouse for use in experiments.

Arabidopsis seedlings were raised as follows. Seeds were surface sterilized for 10 min with one-fifth strength of a NaOCl solution (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan), rinsed with deionized water, and mixed with 0.3% agar. The mixture of agar and seeds was pipetted onto the surface of 0.9% agar that filled a plastic tray (top area, 15.5 × 2.5 cm2; height, 3.3 cm), and a clear, plastic cover (height, 2.8 cm) was placed over it. The prepared seeds were kept at 4°C in the dark for 2 d and subsequently incubated at 25°C. They were exposed to red light (2 μmol m−2 s−1) for 2 h at the beginning of incubation (for the light source, see Wang and Iino, 1997), and then maintained in the dark for 62 h. The plants were incubated for an additional 24 h under red light (2 μmol m−2 s−1). At this stage of growth, plants had rapidly elongating hypocotyls. The average hypocotyl lengths (determined from 50 to 60 seedlings) were 8.4 mm (wild type), 8.2 mm (hy4), 8.1 mm (phyA), 9.3 mm (phyB), and 10.2 mm (phyAphyB). Hypocotyls of typical length were used to prepare protoplasts: approximately 7 to 9 mm (wild type, hy4, and phyA), 8 to 10 mm (phyA), and 9 to 11 mm (phyAphyB).

Preparation of Protoplasts

The upper third of each hypocotyl was excised with a razor blade, and immediately placed into 5 mL of an enzyme solution containing 2% (w/v) cellulase RS (Yakult, Tokyo, Japan), 0.2% (w/v) pectolyase Y-23 (Seishin Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan), 0.8% (w/v) Cellulysin (Calbiochem), 0.45 m sorbitol, 10 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 20 mm Glc, and 5 mm Mes-Tris, pH 5.5. After obtaining hypocotyl segments from about 300 plants over a period of 20 to 30 min, the enzyme solution containing the segments was vacuum infiltrated (10 min at 75 cm of Hg) and rotated on a shaker (65 rpm) for 2.5 h. The mixture was filtered through nylon mesh and centrifuged at 110g for 10 min. The pellet was washed twice by suspending in an incubation medium (5 mL) containing 0.45 m sorbitol, 10 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 20 mm Glc, and 5 mm Mes-Tris, pH 6.0, and centrifuging at 110g for 8 min. The sedimented protoplasts were suspended in a small amount of the incubation medium (200–300 μL) to obtain the final preparation (2 × 105 to 5 × 105 protoplasts mL−1). The osmolality of the incubation medium measured by a vapor pressure osmometer (model 5500, Wescor, Logan, UT) was 510 mosmol. The protoplasts from all of the Arabidopsis strains used showed more than 95% viability when determined by the method of Widholm (1972) at 0.02% (w/v) fluorescein diacetate.

Other than the time of centrifugation, during the entire period of protoplast preparation, tissues and protoplasts were continuously exposed to red light (1–3 μmol m−2 s−1). This red light also served as a working light.

Incubation and Light Treatment of Protoplasts and Measurement of Protoplast Volume

A 200-μL portion of the freshly prepared protoplast suspension was pipetted into a quartz cuvette (five sides clear, base 10 × 10 mm, height 45 mm) and incubated at 25°C ± 1°C on the sample stage of a microscope system, which consisted of an inverted microscope (IMT-2, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), a camera, a sample box made of red plate acrylic, and two actinic light sources (Kodak Ektagraphic III projectors). The cuvette was covered with a glass coverslip during incubation. Unless otherwise specified, protoplasts were exposed to red light (50 μmol m−2 s−1) throughout incubation. This red light, referred to as the background red light, was obtained by filtering the light from the microscope light source through a red interference filter (IF-BPF-640, Vacuum Optics, Tokyo, Japan) and the red acrylic layer of the sample box.

Protoplasts were treated with blue light while being incubated in the microscope system. A blue glass filter (no. 5–50, Corning, Corning, NY) was used to isolate blue light from the actinic light source. In some experiments, protoplasts were treated with red or far-red light, which was obtained by passing light from the actinic light source through a red interference filter (IF-BPF-640, Vacuum Optics) or a far-red filter (2 mm thick, Delaglass, Asahi Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan).

Time-lapse photographs of the protoplasts in a selected microscopic field were obtained during incubation. The negative protoplast images recorded on film were magnified and diameters of each protoplast in a series of photographs were determined. Protoplasts were selected for size, roundness, and clarity of the margin; the selection was otherwise random. The volume of each protoplast was calculated from its diameter.

Details not described here can be found in our previous paper (Wang and Iino, 1997).

Chemical Treatments of Protoplasts

The following chemicals were used to treat protoplasts: vanadium oxide (Aldrich), NPPB (BIOMOL Research Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA), IDA (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto), TEA-Cl (Nacalai Tesque), and EGTA (Nacalai Tesque). Vanadate was prepared from vanadium oxide as the method described by Gallagher and Leonard (1982). NPPB was dissolved in ethanol at 20 mm, and this stock solution was used after dilution with the incubation medium. When Cl− in the incubation medium was replaced with IDA, 14 mm IDA, 10 mm KOH, and 2 mm Ca(OH)2 were used in place of 10 mm KCl and 2 mm CaCl2; when K+ was replaced by TEA+, 10 mm TEA-Cl was used instead of 10 mm KCl.

RESULTS

Size Distribution of Protoplasts

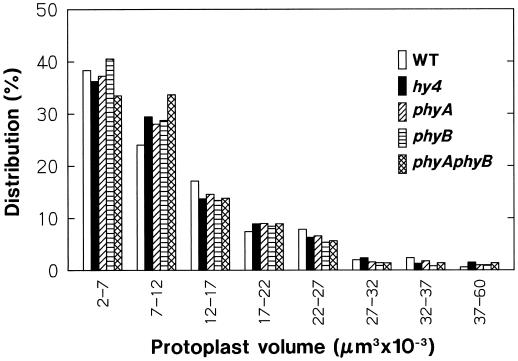

In the present study protoplasts were isolated from the upper part of the hypocotyl of wild-type and mutant seedlings that were 4 d old and adapted to red-light growth conditions. The mutants used were hy4, phyA, phyB, and phyAphyB (for mutant lines, see Methods). Figure 1 shows the volume distribution of wild-type and mutant protoplasts prepared by the standard procedure and adapted to the standard incubation conditions for 1 h. In all of the Arabidopsis strains used, a substantial proportion (65%–70%) of protoplasts occurred in the smallest range, 2 × 103 to 12 × 103 μm3, and the proportion decreased with size. Compared with wild-type protoplasts, the protoplasts from mutants (especially phyAphyB) tended to fall more into the second smallest range (7 × 103 to 12 × 103 μm3). It appeared, however, that the overall distribution pattern for each mutant was similar to that of wild-type protoplasts.

Figure 1.

Size distribution of the protoplasts from hypocotyls of wild-type Arabidopsis (Landsberg erecta) and its mutants hy4–1 (hy4), phyA-201 (phyA), phyB-5 (phyB), and phyA-201/phyB-5 (phyAphyB). Protoplasts were isolated under red light (1–3 μmol m−2 s−1) from the upper third of hypocotyls of 88-h-old seedlings that had been exposed to red light (2 μmol m−2 s−1) for the last 24 h. Freshly isolated protoplasts, washed with and suspended in a medium containing 0.45 m sorbitol, 10 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 20 mm Glc, and 5 mm Mes-Tris, pH 6.0, were added to the measurement cuvette and incubated under red light (50 μmol m−2 s−1) in the microscope system. Protoplast sizes were determined from the photographs obtained at 1 h of incubation. The proportion in each size range is given as a percentage of the number of protoplasts (460–500) examined.

In the following experiments, the protoplasts in the range from 5 × 103 to 30 × 103 μm3 were subjected to the volume analysis. In all of the plant strains used, about 75% of protoplasts occurred in this range. To investigate whether the protoplast responses to experimental treatments depend on the size of protoplasts within the range defined, the analysis was additionally conducted for protoplasts from two narrower ranges, 5 × 103 to 12 × 103 μm3 (small protoplasts) and 17 × 103 to 30 × 103 μm3 (large protoplasts).

Protoplast Swelling under Background Red Light

In our standard procedure the cuvette containing a protoplast suspension was placed on the microscope stage about 1 min after preparation of the final suspension, and the protoplasts were thereafter incubated under constant red light (50 μmol m−2 s−1). When the volume of wild-type protoplasts was monitored after 10 min of incubation (the time required for sedimentation of protoplasts to the bottom of the cuvette), it changed little for about 30 min and thereafter increased steadily for at least 1.5 h. Based on this result, we decided to allow protoplasts to stand for at least 40 min after the onset of incubation before initiating experimental monitoring of the protoplast volume.

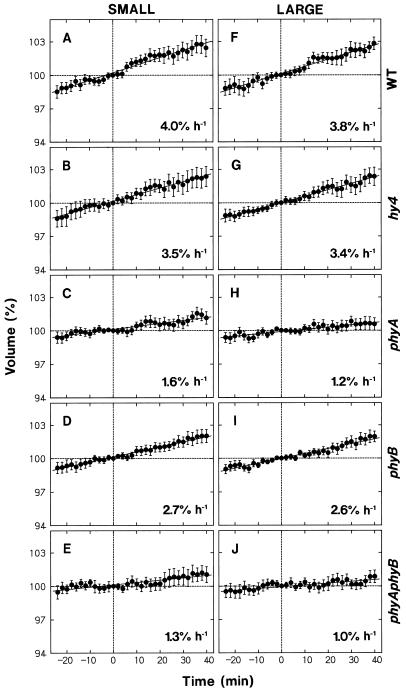

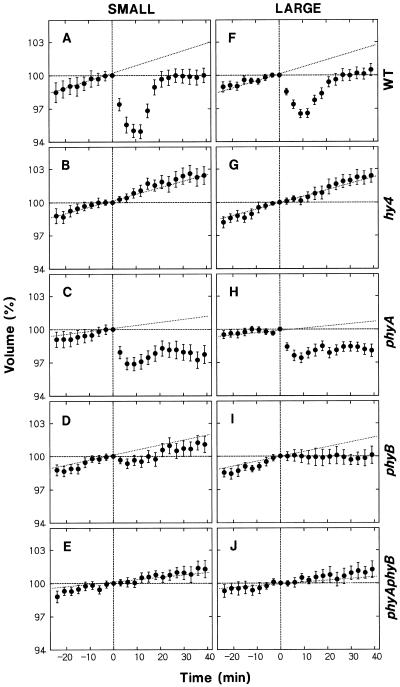

The observed swelling of protoplasts was investigated further using wild-type and mutant protoplasts. The experiments were planned so that the data would also serve as the controls for blue-light responses. The results obtained separately for small and large protoplasts are summarized in Figure 2. The measured protoplast volume at a given time was calculated as the value relative to the volume determined 65 min after the onset of incubation (time 0 in Fig. 2), which corresponded to the time at which blue-light stimulation was initiated in most of the experiments described below.

Figure 2.

Changes in the volume of protoplasts during incubation under red light. Protoplasts of the wild type (A and F, WT) and mutants (B and G, hy4; C and H, phyA; D and I, phyB; and E and J, phyAphyB) of Arabidopsis, isolated and incubated under red light as described for Figure 1, were subjected to time-lapse photography (2-min intervals). Time 0 (abscissa) was adjusted to 65 min after the onset of incubation, and corresponded to the time at which blue-light treatment was initiated in most of the following experiments. The protoplasts that fell into two volume ranges at time 0 were analyzed separately: 5 × 103 to 12 × 103 μm3 (small protoplasts, left panels) and 17 × 103 to 30 × 103 μm3 (large protoplasts, right panels). The volume of each protoplast at a given time was calculated as a percentage of the volume at time 0. The means ± se from 20 to 28 protoplasts are shown. The solid line in each panel represents the linear regression line, and the figures indicate the slope.

As shown in Figure 2, A and F, wild-type protoplasts swelled at a nearly constant rate. Small and large protoplasts showed similar swelling rates, approximately 4% h−1. The protoplasts from hy4 (Fig. 2, B and G) and phyB (Fig. 2, D and I) mutants swelled at rates comparable to or slightly lower than the rate in the wild type. The protoplasts from phyA and phyAphyB mutants also swelled but at much reduced rates.

The results indicated that the observed protoplast swelling was mediated by phytochrome. The Pfr produced by the background red light was probably responsible for the swelling. Because the swelling rate in phyB protoplasts was closer to that in wild-type protoplasts and the rate in phyA protoplasts was as low as that in phyAphyB protoplasts, phytochrome A appeared to be the major phytochrome species involved.

Protoplast Shrinking Induced by a Pulse of Blue Light

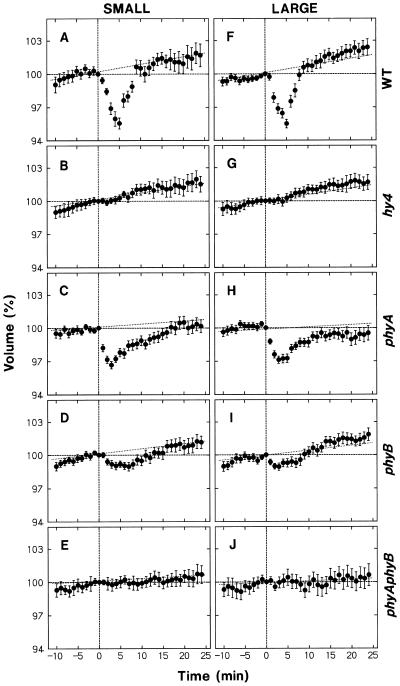

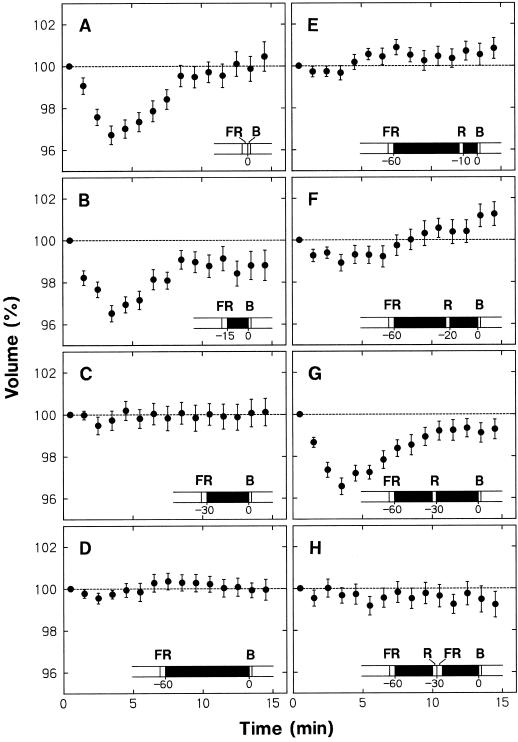

The effect of blue light on protoplast volume was investigated by exposing the protoplasts to a 30-s pulse. This blue-light pulse was given in addition to the background red light and provided a fluence of 3.5 mmol m−2, found to be sufficient to saturate the shrinking response of maize protoplasts (Wang and Iino, 1997). Figure 3 shows the results obtained for small and large protoplasts from wild-type Arabidopsis and mutants. Time 0 denotes the onset of the blue-light pulse.

Figure 3.

Protoplast shrinking induced by a blue-light pulse. Protoplasts of the wild type (A and F, WT) and mutants (B and G, hy4; C and H, phyA; D and I, phyB; and E and J, phyAphyB) of Arabidopsis, isolated and incubated under red light as described for Figure 1, were subjected to time-lapse photography (1-min intervals). Protoplasts were exposed to a 30-s pulse of blue light (fluence: 3.5 mmol m−2) immediately after obtaining the photograph at time 0, which was 65 min after the onset of incubation. The volume of small protoplasts (left panels) and large protoplasts (right panels) was analyzed as described for Figure 2. The means ± se from 18 to 40 protoplasts are shown. Dotted lines reproduce the regression lines of Figure 2.

Small and large protoplasts from wild-type Arabidopsis showed similar transient shrinkage in response to blue light (Fig. 3, A and F). The volume decreased immediately following blue-light stimulation and reached a minimum (about 95% of the initial volume) at about 5 min. After this point, the protoplasts swelled and recovered their volume over a period of about 5 min, eventually reaching the control level (dotted lines).

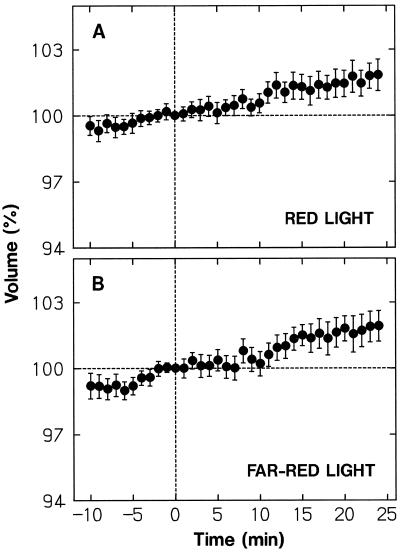

Although the blue-light pulse was given while protoplasts were continuously exposed to background red light, it would transiently affect the level of Pfr. To investigate whether the observed protoplast shrinkage was induced by a change in Pfr level, we treated protoplasts with a high-fluence pulse of red light (7.6 mmol m−2) or far-red light (9.0 mmol m−2). Figure 4 shows the results obtained by analyzing protoplasts in the volume range from 5 × 103 to 30 × 103 μm3. No appreciable change in volume was induced by either red light (Fig. 4A) or far-red light (Fig. 4B). No change was detected even if small and large protoplasts were separately analyzed (not shown). The results demonstrated that the protoplast shrinking response to blue light was not mediated by phytochrome.

Figure 4.

Effects of a pulse of red light or far-red light on the volume of protoplasts. While being incubated under background red light the wild-type protoplasts were exposed to a 30-s pulse of red light (7.6 mmol m−2) (A) or far-red light (9.0 mmol m−2) (B) immediately after time 0. To obtain the required fluence of far-red light, two projector light sources were used. The protoplasts that were in the volume range from 5 × 103 μm3 to 30 × 103 μm3 at time 0 were analyzed. The means ± se from 30 to 32 protoplasts are shown. Other details are as described in Figure 3.

The protoplasts from hy4 (Fig. 3, B and G) and phyAphyB (Fig. 3, E and J) mutants failed to show any detectable shrinking in response to blue light. Because phytochrome is not the photoreceptor for the blue-light response, it is concluded that blue light is perceived by the photoreceptor CRY1, the product of the HY4 gene (see the introduction), whereas the responsiveness to blue light depends on the presence of phytochromes A and B. The protoplasts from the phyA mutant showed a shrinking response that was about 60% of that in wild-type protoplasts (Fig. 3, C and H). The phyB protoplasts showed a shrinking response (Fig. 3, D and I), but the response was much less than in wild-type and phyA protoplasts. The results indicated that phytochrome B contributes more than phytochrome A to blue-light responsiveness.

Protoplast Shrinking Induced by Continuous Blue Light

The effect of continuous blue light was next investigated. The fluence rate was fixed at 70 μmol m−2 s−1, which was sufficient to saturate the shrinking response in maize protoplasts (Wang and Iino, 1997). The results obtained using small and large protoplasts from wild-type Arabidopsis and mutants are shown in Figure 5. Time 0 denotes the time at which blue-light stimulation commenced.

Figure 5.

Protoplast shrinking induced by continuous blue light. Protoplasts from the wild type (A and F) and mutants (B and G, hy4; C and H, phyA; D and I, phyB; and E and J, phyAphyB) of Arabidopsis, isolated and incubated under red light as described for Figure 1, were subjected to time-lapse photography (3-min intervals). Protoplasts were exposed to blue light (70 μmol m−2 s−1) continuously from time 0, which was 65 min after the onset of incubation. The volume of small protoplasts (left panels) and large protoplasts (right panels) was analyzed as described for Figure 2. The means ± se from 18 to 29 protoplasts are shown. Dotted lines reproduce the regression lines of Figure 2.

The wild-type protoplasts shrank immediately following the onset of stimulation; after establishing a minimum at about 10 min, the protoplasts swelled and recovered their volume over a period of about 10 min (Fig. 5, A and F). Small and large protoplasts showed similar shrinking and recovery kinetics, although the relative extent of shrinking was somewhat smaller in large than in small protoplasts.

The time-course data described above indicated that, as in the case of maize protoplasts (Wang and Iino, 1997), the response to continuous stimulation is transient. Unlike maize protoplasts, however, Arabidopsis protoplasts did not recover their volume to the control level (Fig. 5, A and F). It is unlikely that this difference was due to the continuous swelling that progressed in the control protoplasts, because maize protoplasts recovered to the volume of the control protoplasts, which swelled similarly under background red light. Furthermore, when stimulated with a blue-light pulse, Arabidopsis protoplasts recovered to the control level (Fig. 3, A and F) as did maize protoplasts (Wang and Iino, 1997), indicating that the volume can return to the control level when the effect of blue light disappears. We conclude that the response of Arabidopsis protoplasts to continuous stimulation includes a long-persisting response in addition to a transient one.

In agreement with the results obtained with pulse stimulation, the protoplasts from hy4 (Fig. 5, B and G) and phyAphyB (Fig. 5, E and J) mutants did not show any detectable response, and the protoplasts from phyA (Fig. 5, C and H) and phyB (Fig. 5, D and I) mutants showed a partial response. In further agreement, the response was smaller in phyB than in phyA protoplasts. Therefore, the conclusions about the mediating photoreceptor and the phytochrome regulation of blue-light responsiveness obtained with pulse stimulation are all applicable to the response to continuous stimulation.

The transient response in phyA protoplasts was about one-half of that in wild-type protoplasts, whereas the long-persisting response was the same in both (Fig. 5; compare C and H with A and F). It is suggested that the transient response, but not the long-persisting response, is impaired by phyA mutation. In phyB protoplasts the transient response was not apparent, and the long-persisting response was smaller than in wild-type protoplasts (Fig. 5, D and I). Thus, both responses are impaired by the phyB mutation. However, the transient response appeared to be impaired to a greater extent than the long-persisting one.

There was no fundamental difference between small and large protoplasts in swelling under background red light (Fig. 2) and the blue-light-induced shrinking (Figs. 3 and 5) if the protoplast volume is expressed as a percentage of the initial volume. In the following experiments we continued to analyze small and large protoplasts separately. However, since the results were similar, we present only those data obtained for the full range (5 × 103 to 30 × 103 μm3).

Dependence of Blue-Light-Induced Protoplast Shrinking on Phytochrome

We conducted a series of experiments with wild-type protoplasts to investigate further the phytochrome regulation of the blue-light responsiveness. The data shown in Figure 6, A to D, were obtained to resolve the effect of dark pretreatment on the protoplast shrinking response. In these experiments protoplasts were first incubated under background red light. After 20 min of incubation, red-light irradiation was terminated, and protoplasts were exposed to far-red light for 3 min to transform Pfr to Pr. The fluence of far-red light was 27 mmol m−2, which is generally sufficient to saturate the phototransformation. The protoplasts were subsequently incubated in the dark for different periods and then stimulated with a 30-s pulse of blue light. After this pulse, the background irradiation with red light was resumed, and the protoplasts were subjected to time-lapse photography. Time 0 denotes the onset of the blue-light pulse.

Figure 6.

Dependence on phytochrome of the blue-light-induced shrinking in wild-type protoplasts. The background red light was terminated at 20 min of incubation (see Fig. 1), and the protoplasts were subjected to various treatments (A–H described below; also illustrated), which included a dark period, a far-red-light pulse (3 min, 27 mmol m−2), and a red-light pulse (90 s, 4.5 mmol m−2). The protoplasts were then stimulated with a blue-light pulse (30 s, 3.45 mmol m−2), and background irradiation with red light was resumed. Time 0 represents the onset of blue-light stimulation. The volume of each protoplast at a given time was calculated as a percentage of the volume measured immediately after blue-light stimulation. The protoplasts that were initially in the volume range from 5 × 103 to 30 × 103 μm3 were analyzed. A through D, Protoplasts were stimulated with a blue-light pulse after pretreatments with a pulse of far-red light and a subsequent period of darkness; dark periods between the far-red-light and the blue-light pulse were 0 (A), 15 (B), 30 (C), and 60 (D) min. E through G, Protoplasts were stimulated with a blue-light pulse after pretreatments with a far-red-light pulse and a subsequent 60-min dark period interrupted with a red-light pulse. The dark intervals between the red-light and the blue-light pulse were 10 (E), 20 (F), and 30 (G) min. H, Protoplasts were treated with a red-light pulse as in G, but a pulse of far-red light was given immediately after the red-light pulse. The means ± se from 20 to 39 protoplasts are shown.

When the blue light was given after the far-red light without a delay (Fig. 6A) or with a 15-min dark interval (Fig. 6B), a normal shrinking response took place (compare with Fig. 3, A and F). No such response was apparent, however, when the dark interval was 30 min (Fig. 6C) or 60 min (Fig. 6D). The results indicated (a) that the protoplasts lose their ability to respond to blue light when Pfr has been absent for a period longer than 30 min, and (b) that the disappearance of blue-light responsiveness progresses in a narrow time range from 15 to 30 min after the conversion of Pfr to Pr. The loss of shrinking response (Fig. 6, C and D) was observed even though the protoplasts were continuously exposed to red light after blue-light stimulation. Clearly, Pfr produced after the blue-light stimulation was without an effect.

In the next experiments (Fig. 6, E–G), the dark interval before blue-light stimulation was fixed at 60 min; during this interval, the protoplasts were treated with red light for 90 s (fluence, 4.5 mmol m−2). No shrinking was detected when this red-light pulse was given 10 min before blue-light stimulation (Fig. 6E), but normal shrinking followed when it was given 30 min before blue-light stimulation (Fig. 6G). Slight shrinking was detected when the red light was given 20 min before blue-light stimulation (Fig. 6F). These results indicated (a) that the dark-treated protoplasts begin to respond to blue light again when Pfr is produced in advance, (b) that the production of Pfr does not result in immediate establishment of blue-light responsiveness (a period of at least 10 min is required before the responsiveness begins to be established), and (c) that the responsiveness is fully established 30 min after Pfr is produced. It is apparent that the establishment of blue-light responsiveness progressed in a narrow time range from about 15 to 30 min after the appearance of Pfr.

The effect of the red-light pulse in establishing the blue-light responsiveness (Fig. 6G) was canceled by the far-red-light pulse given immediately after the red light (Fig. 6H), providing additional evidence for the phytochrome control of blue-light responsiveness.

Important conclusions emerge from the results presented above. The active form of Pfr does not directly interact with the blue-light receptor or any other component involved in the blue-light response. The blue-light responsiveness depends on components generated by the action of Pfr. The kinetic data indicate that the immediate component required for blue-light responsiveness, referred to as X, begins to be produced about 15 min after the appearance of Pfr and is sufficiently established within the next approximately 15 min. (This interpretation also takes into consideration the fact that the lag between blue-light perception and the occurrence of shrinking response is very short, within 1 min.) Component X also begins to disappear about 15 min after the removal of Pfr and is lost within the next 15 min.

Under the conditions in which the blue-light-induced shrinking response was eliminated by dark pretreatment, protoplast swelling was also undetectable (Fig. 6, C and D). Therefore, it appeared that the protoplast swelling shown to be mediated by phytochrome was in fact induced by the background red light.

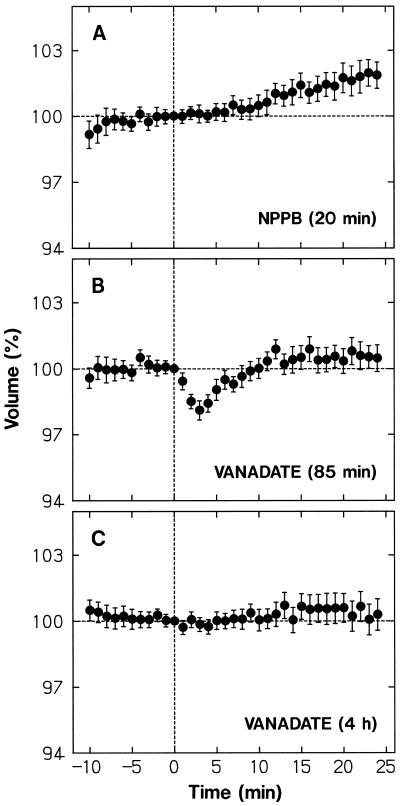

Effects of NPPB and Vanadate

The anion-channel blocker NPPB (Marten et al., 1992) effectively inhibited the protoplast shrinking response of maize coleoptile protoplasts (Wang and Iino, 1997), supporting the conclusion of Cho and Spalding (1996; see the introduction). We conducted similar experiments with the protoplasts from wild-type Arabidopsis. As shown in Figure 7A, the shrinking response to a blue-light pulse was inhibited almost entirely by 15 μm NPPB added to the incubation medium 20 min before blue-light stimulation.

Figure 7.

Effects of NPPB and vanadate on blue-light-induced protoplast shrinking. The wild-type protoplasts treated with NPPB or vanadate as described below were stimulated with a blue-light pulse immediately after time 0. A, NPPB (15 μm) was added to the incubation medium 20 min before stimulation. B, Vanadate (500 μm) was added to the medium used to wash protoplasts and to obtain the final protoplast suspension (about an 85-min treatment before stimulation). C, Vanadate (500 μm) was added to the enzyme solution used to obtain protoplasts and to the incubation medium as in B (a total of about 4 h treatment before stimulation). The protoplasts that were in the volume range from 5 × 103 to 30 × 103 μm3 at time 0 were analyzed. The means ± se from 20 to 31 protoplasts are shown. Other details are as described in Figure 3.

We also examined the effect of vanadate, an inhibitor of plasma membrane H+-pumps (H+-ATPase). When vanadate (500 μm) was added to the incubation medium from the step of protoplast washing, the blue-light response was partially inhibited (Fig. 7B). In this experiment, protoplasts were in contact with vanadate for about 85 min before blue-light stimulation. When vanadate was also added to the enzyme solution, the response was inhibited almost entirely (Fig. 7C). Tissues and protoplasts were in contact with vanadate before blue-light stimulation for a total period of about 4 h. The results indicated that the blue-light response cannot take place when the H+-pump is inhibited in advance. The long pretreatment required for complete inhibition probably represents the low permeability of plasma membranes to vanadate (Amodeo et al., 1992).

The data additionally indicated that the swelling under background red light took place normally in NPPB-treated protoplasts (Fig. 7A), whereas it was substantially suppressed by vanadate (Fig. 7C). Therefore, the swelling appeared to depend on the H+-pump activity, but not on the anion-channel activity.

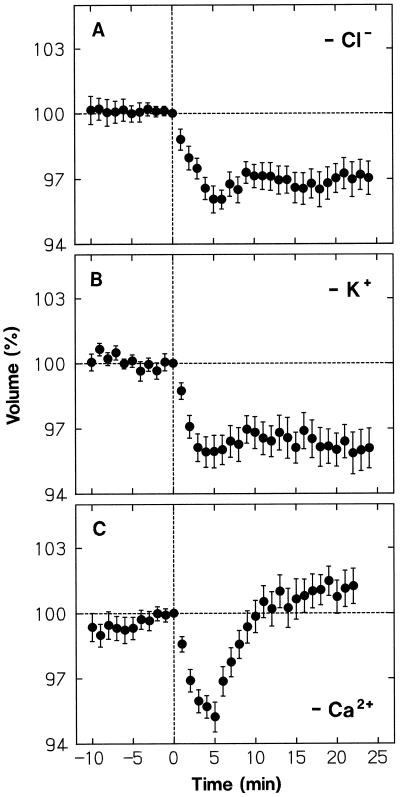

Dependence on Ion Composition and pH of the Bathing Medium

The wild-type protoplasts were suspended in modified incubation medium to investigate the contribution made by each component of the standard medium in the blue-light response. A modified incubation medium was used, unless otherwise specified, from the step of protoplast washing, thus bathing the protoplasts in the medium for about 85 min before blue-light stimulation.

When Cl− of the medium was replaced by the impermeant anion IDA, protoplasts showed normal shrinking in response to a blue-light pulse (Fig. 8A; compare with Fig. 3, A and F). However, after establishing the minimal volume at about 5 min, the protoplasts almost retained the reduced volume. As shown in Figure 8B, a nearly identical result was obtained when K+ was replaced by the impermeant cation TEA+, which also acts as a K+-channel blocker (Brown, 1993). The results indicated that the volume recovery is achieved by uptake of Cl− and K+, both ions being required for continuation of the uptake of either ion.

Figure 8.

Dependence of the protoplast shrinking response to a blue-light pulse on K+, Cl−, and Ca2+ of the bathing medium. The wild-type protoplasts, isolated as described for Figure 1, were washed with and suspended in the modified incubation media listed below (see Fig. 1 for the basic medium composition). The protoplasts were stimulated with a blue-light pulse immediately after time 0, which was 65 min (A and B) or 50 min (C) after the onset of incubation. A, Cl− in the medium was replaced by IDA (14 mm IDA, 10 mm KOH, and 2 mm Ca[OH]2 were used instead of 10 mm KCl and 2 mm CaCl2). B, K+ in the medium was replaced by TEA+ (10 mm TEA-Cl was used instead of 10 mm KCl). C, CaCl2 in the medium was omitted and 1 mm EGTA was added to the final suspension medium. The protoplasts that were in the volume range from 5 × 103 to 30 × 103 μm3 at time 0 were analyzed. The means ± se from 19 or 20 protoplasts are shown. Other details are as described in Figure 3.

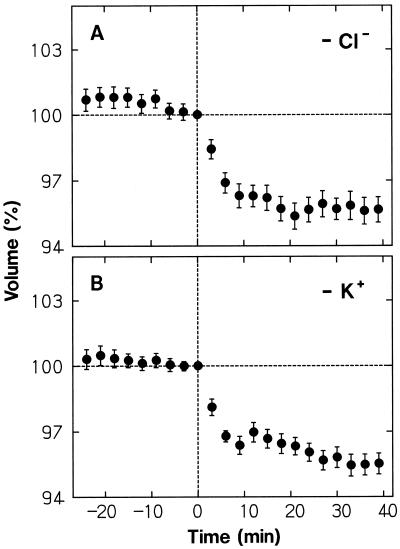

Ion replacement effects were next investigated with continuous blue-light stimulation. When Cl− was replaced by IDA (Fig. 9A) or K+ was replaced by TEA+ (Fig. 9B), the protoplasts showed a nearly normal shrinking response, but failed to recover their volume (compare with Fig. 5, A and F). Therefore, the volume recovery during continuous stimulation also appeared to be achieved by uptake of Cl− and K+, with the requirement of the presence of both ions.

Figure 9.

Dependence of the protoplast shrinking response to continuous blue light on Cl− and K+ of the bathing medium. The wild-type protoplasts, washed with and suspended in the following modified incubation media, were stimulated with blue light (70 μmol m−2 s−1) from time 0. A, Cl− in the medium was replaced by IDA. B, K+ in the medium was replaced by TEA+. The means ± se from 21 to 23 protoplasts are shown. Other details are as described in Figures 5 and 8.

The response of protoplasts to a blue-light pulse, including the volume recovery, took place normally when CaCl2 or Glc was omitted from the incubation medium (not shown). Therefore, external Ca2+ and Glc were not used as the osmotic substances for volume recovery. To resolve whether Ca2+ in the medium was entirely unnecessary for the blue-light response, we added 1 mm EGTA to the medium from which CaCl2 was omitted. Since protoplasts were broken in this Ca2+-free medium at a relatively high rate (about 20% h−1), the incubation time before blue-light stimulation was shortened from 65 to 50 min, which still allowed the minimal adaptation time of 40 min before the onset of volume monitoring, and only those protoplasts which were intact during the measurement period were analyzed. As shown in Figure 8C, the shrinking response and the subsequent volume recovery took place normally in this Ca2+-free medium.

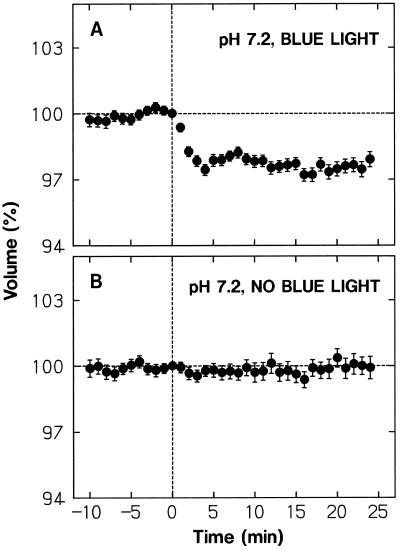

The K+ influx during the volume recovery can be driven by the inside-negative membrane potential. It is not clear, however, how Cl− influx occurs against the membrane potential and the concentration gradient. One possibility is that Cl− enters the cell via a Cl−/H+ symporter driven by the proton motive force. If this were the case, one would expect that the volume recovery cannot take place when the medium pH is close to the cytosolic pH, which is usually around 7.0. The data shown in Figure 10A were obtained using a medium adjusted to pH 7.2 (instead of pH 6.0). Clearly, the protoplasts could not recover their volume after a shrinking response (compare with Fig. 10B obtained without blue-light stimulation). The extent of shrinking was smaller than that at the standard pH (Fig. 3, A and F). Although this part of the pH effect could not be explained clearly, the data at least demonstrated that the volume does not recover at neutral pH, supporting the idea that Cl− uptake is mediated by a Cl−/H+ symporter.

Figure 10.

Blue-light-induced protoplast shrinking at neutral pH. The wild-type protoplasts, isolated as described for Figure 1, were washed with and suspended in the incubation medium adjusted to pH 7.2 with Tris. A, The protoplasts were stimulated with a blue-light pulse immediately after time 0. B, Protoplasts were not stimulated with blue light, but were otherwise treated as in A. The protoplasts that were in the volume range from 5 × 103 to 30 × 103 μm3 at time 0 were analyzed. The means ± se from 67 (A) or 38 (B) protoplasts are shown. Other details are as described in Figure 3.

Effects of medium modifications on the swelling under background red light could be evaluated from the time-course data obtained before blue-light stimulation. The swelling was not observed when Cl− and K+ were replaced by IDA and TEA+, respectively (Fig. 8, A and B; Fig. 9), but when Ca2+ (Fig. 8C) or Glc (not shown) was omitted from the medium. Therefore, it appeared that, as in the case of the volume recovery after blue-light-induced shrinkage, the phytochrome-mediated swelling is achieved by uptake of Cl− and K+. Furthermore, the swelling did not take place at neutral pH (Fig. 10B), suggesting that the proton motive force is also essential for this ion uptake.

DISCUSSION

Protoplast Shrinking Response and Its Relationship to Growth

We have demonstrated that protoplasts isolated from Arabidopsis hypocotyls shrink in response to blue light. The extent and kinetics of the response induced by either a blue-light pulse (Fig. 3, A and F) or continuous blue light (Fig. 5, A and F) were similar to those found in maize coleoptile protoplasts (Wang and Iino, 1997). Also, most of the isolated protoplasts were responsive, as in maize. More importantly, the blue-light-induced shrinking of Arabidopsis protoplasts did not occur in hy4 and phyAphyB mutants (Figs. 3 and 5). These results, together with those obtained using red- and far-red light treatments (Figs. 4 and 6), demonstrate that the blue-light response itself is mediated by the photoreceptor CRY1 (Ahmad and Cashmore, 1993; Lin et al., 1995a, 1995b), whereas the blue-light responsiveness is controlled by phytochrome.

When stimulated with continuous blue light, maize protoplasts shrank rapidly, but stopped shrinking at 6 to 10 min of stimulation and subsequently swelled, recovering their volume to near the control level (Wang and Iino, 1997). This transient nature of the response to continuous stimulation was also evident in Arabidopsis, although the recovery of the volume was obviously incomplete (Fig. 5, A and F). This incomplete recovery has indicated that the response of Arabidopsis protoplasts includes a long-persisting response in addition to a transient one. This conclusion does not imply that the two responses are based on distinct photosystems. In fact, both responses appear to be mediated by CRY1, because hy4 protoplasts did not show any detectable response over the period of stimulation in which the transient and long-persisting responses could be identified.

Analyses with maize protoplasts have provided evidence for the participation of photosensory adaptation in the shrinking response to continuous blue light (Wang and Iino, 1997). It is probable that the transience of the response is based on this adaptation mechanism and that the long-persisting response represents the steady-state response level established after adaptation. Perhaps the steady-state response at a given fluence rate of blue light is much greater in Arabidopsis than in maize.

Some lines of evidence have indicated that the shrinking response of maize protoplasts represents a mechanism that is involved in the blue-light-dependent inhibition of coleoptile growth rather than blue-light-dependent coleoptile phototropism (Wang and Iino, 1997). The present results obtained with the hy4 mutant (see above) have further substantiated the causal relationship between the protoplast shrinking response and the blue-light-dependent growth inhibition.

The CRY1-mediated inhibition of Arabidopsis hypocotyl growth has so far been identified by measuring growth after long-term blue-light stimulation (Koorneef et al., 1980; Ahmad and Cashmore, 1997). The long-persisting component of the protoplast shrinking response can explain this growth inhibition. In maize coleoptiles the growth was rapidly inhibited following the onset of continuous blue light and, after several minutes of inhibition, the growth rate increased to approach the control level, showing an essential agreement with the transient protoplast response (Wang and Iino, 1997). Whether the transient phase of the protoplast shrinking response in Arabidopsis results in a corresponding inhibition of hypocotyl growth remains to be investigated.

Growth of dark-adapted cucumber hypocotyls (Cosgrove, 1981) and red-light-grown (Laskoswki and Briggs, 1989) and dark-adapted (Kigel and Cosgrove, 1991) pea internodes was rapidly inhibited after the onset of continuous blue light, but remained fully inhibited over a period of stimulation that exceeds the transient phase of the protoplast shrinking response identified in our studies. In fact, the transient phase of growth inhibition has so far been found only with maize coleoptiles. It is perhaps worthwhile to note that the transient phase of the protoplast shrinking response was less evident when either phytochrome A (Fig. 5, C and H) or B (Fig. 5, D and I) was unable to function. Clear occurrence of the transient phase of growth inhibition may depend on the level of Pfr before and/or during blue-light stimulation and hence on the light conditions used: e.g. whether plants were adapted to red light or to darkness, or, in the latter case, whether green working lights were used. Furthermore, the transient phase of the protoplast shrinking response could not be identified when K+ or Cl− was not available in the bathing medium (Fig. 9). It is possible that clear occurrence of the transient growth inhibition also depends on the nutritional conditions of plants. These possibilities warrant further studies.

Cellular Mechanisms of Blue-Light-Induced Protoplast Shrinking

Using the cell-attached mode of the patch-clamp technique, Cho and Spalding (1996) provided evidence that plasma membrane anion channels (Cl− channels) of Arabidopsis hypocotyls are activated by blue light. Furthermore, the blue-light-induced plasma membrane depolarization could be attributed to Cl− efflux through the activated channels because NPPB inhibited the depolarization.

The blue-light-induced shrinking of maize (Wang and Iino, 1997) and Arabidopsis (Fig. 7A) protoplasts is effectively inhibited by NPPB. Therefore, the shrinking response can also be attributed to the anion-channel activation. How, then, do protoplasts shrink in response to anion-channel activation? On this question, it is perhaps significant to realize that the depolarization response is more transient than the shrinking response. In cucumber hypocotyls the plasma membrane was maximally depolarized about 1 min after the onset of continuous blue light and repolarized near to the original level within the next 2 min (Spalding and Cosgrove, 1989). In Arabidopsis hypocotyls a similar transient depolarization followed a blue-light pulse (Cho and Spalding, 1996; Lewis et al., 1997). It is apparent that the plasma membrane is already in the repolarizing and fully repolarized phases when the protoplasts undergo a major part of the shrinking (Figs. 3 and 5, A and F).

A contribution of K+ efflux has been implicated for the repolarization phase of the action potential in Nitella axilliformis (Shimmen and Tazawa, 1983). By analogy to this model, we hypothesize that certain outward-rectifying K+ channels (Schroeder et al., 1987; Hosoi et al., 1988; Roberts and Tester, 1995) are activated after the anion-channel activation, allowing facilitated K+ efflux and membrane repolarization, and that enhanced effluxes of both Cl− and K+ continue, allowing protoplasts to shrink under the repolarized condition. The K+ channels may be activated in response to membrane depolarization (Hosoi et al., 1988; Roberts and Tester, 1995). However, to explain the nearly complete repolarization (Spalding and Cosgrove, 1989; Cho and Spalding, 1996) and the effluxes of Cl− and K+ assumed to continue under the repolarized condition, some additional mechanism may have to be considered for the K+-channel activation.

The replacement of the medium K+ by TEA+, a K+-channel blocker, little affected the rate or the extent of shrinking (Figs. 8B and 9B). This result raises a question about the involvement of outward-rectifying K+ channels in the shrinking response (for the effect of TEA+ in the bathing medium, see Roberts and Tester, 1995). A TEA+-insensitive outward-rectifying cation channel has been identified in endosperm cells of Heamanthus and Clivia fruits (Stoeckel and Takeda, 1989). This channel is characterized by low selectivity among monovalent cations and Ca2+-dependent activation. A similar cation channel having a relatively weak outward-rectifying property was identified in epidermal cells of pea leaves (Elzenga and Volkenburgh, 1994). Such TEA+-insensitive cation channels may be responsible for the suggested K+ efflux.

The plasma membrane anion channels so far characterized appear to require a rise in cytosolic Ca2+ for their full activity (Schroeder and Hagiwara, 1989; Hedrich et al., 1990; Okihara et al., 1991), which raises the possibility that blue light might activate anion channels by elevating cytosolic Ca2+. However, Lewis et al. (1997) have recently demonstrated that the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in Arabidopsis hypocotyls does not change after blue-light stimulation. We found a normal protoplast response in the absence of external Ca2+ (Fig. 8C). This result supports the conclusion of Lewis et al. (1997) and indicates that control of Ca2+ influx is not included in the entire process leading to protoplast shrinking, and also not in the process of volume recovery discussed below.

Inhibition of the plasma membrane H+-pump activity might be a primary reaction that follows blue-light perception. Consistent with this idea is the effects of vanadate in preventing blue-light-induced membrane depolarization (Spalding and Cosgrove, 1992) and protoplast shrinking (Fig. 7, B and C). However, Cho and Spalding (1992) showed that a substantial portion of blue-light-induced depolarization can be inhibited by NPPB, which probably does not affect the H+-pump activity. When the protoplast volume was monitored for 3 h after vanadate addition, it did not significantly decrease below the initial value, although the swelling under background red light was inhibited considerably (data not shown). This result indicated that the net ion efflux cannot be enhanced by depolarization alone to the extent caused by blue-light treatment. Furthermore, if the blue-light-induced changes in membrane potential reflect the H+-pump activity, it follows that protoplasts continue to shrink (i.e. the net ion efflux is kept enhanced) even after the membrane is repolarized (i.e. the H+ pump is reactivated). It would be difficult to conceive of such a relationship between pump activity and ion flux. Perhaps the observed effects of vanadate are indirect ones resulting from the vanadate-induced membrane depolarization. It is possible that Cl− efflux through the activated channels, a primary reaction that follows blue-light stimulation, cannot effectively take place when the membrane is depolarized (i.e. when the driving force for Cl− efflux is reduced) and that the activation of outward-rectifying K+ channels, which is somehow linked to anion-channel activation, cannot follow.

The osmolality inside the protoplast is maintained at a value nearly identical to that of the bathing medium. Therefore, on the basis of the volume change data, the extent and the rate of net ion flux can be quantitatively evaluated. The maximal volume reduction achieved by blue-light stimulation was about 5% (Figs. 3 and 5, A and F). If it is assumed that the protoplast shrinks by extruding equal amounts of K+ and Cl−, the amount of either ion needed to achieve this volume reduction is 14 mm at the initial protoplast volume (calculated without considering intracellular compartmentation and using the osmotic coefficient of 0.9). Plant cells typically contain 100 to 200 mm K+ (Wyn Jones et al., 1979). Perhaps the protoplasts used in the present study contain K+ sufficient to achieve the 5% volume reduction. The cellular concentration of Cl− is generally lower than that of K+ and can be as low as 20 mm (Wyn Jones et al., 1979). The protoplasts may lose a substantial portion of their Cl− content when responding to blue light, or other anions may also be extruded substantially for volume reduction. The rates of net ion efflux can be estimated from the slope of volume reduction. The maximal rate of volume reduction, which was recorded after pulse stimulation (Fig. 3, A and F), was about 1.4% min−1 for either small or large protoplasts (calculated from three points between 1 and 3 min). The estimated efflux rate per protoplast surface area of either K+ or Cl− was 0.27 μmol m−2 s−1 when the protoplast volume was 8 × 103 μm−3, which represents the small protoplast. The value was 0.38 μmol m−2 s−1 when the protoplast volume was 23 × 103 μm−3, which represents the large protoplast.

Taking all available results into consideration, we propose the following transduction sequence for the protoplast shrinking response: (a) blue light is perceived by the photoreceptor CRY1, (b) anion channels are activated, (c) Cl− is extruded through the activated channels and the plasma membrane is depolarized, (d) outward-rectifying cation channels are activated, (e) K+ is extruded through the activated channels and the plasma membrane is repolarized, and (f) Cl− (and possibly other anions) and K+ continue to leak through the channels, resulting in the observed decrease in protoplast volume.

Cellular Mechanisms of Volume Recovery

The results shown in Figures 8 and 9 and other data not shown (see Results) have demonstrated that the recovery of protoplast volume after blue-light-induced shrinkage is achieved by uptake of K+ and Cl−. Cl− ions have to be taken up against the membrane potential and the concentration gradient. Uptake of Cl− via an electrogenic Cl−/H+ symporter, which translocates one Cl− with two H+, has been suggested in Chara corallina (Beilby and Walker, 1981) and Sinapis alba root-hair cells (Felle, 1994). In support of the possible contribution of such a symporter, the protoplasts could not recover their volume when incubated in a medium adjusted to neutral pH (Fig. 10).

The ion uptake during the volume recovery probably represents the uptake mechanisms that normally function in the steady-state conditions before blue-light stimulation. The uptake rates for K+ and Cl− are expected to be greater in the recovery phase than those in the steady state because of the lower intracellular concentrations of K+ and Cl−. It is possible, however, that the uptake is facilitated further by activation of channels and/or symporters (note that the rate of volume change during the recovery phase can be as fast as the rate during the shrinking phase; Fig. 3, A and F). If Cl− uptake is mediated by a symporter and if the H+-pump activity is not significantly enhanced, net influxes of K+ and Cl− representing the volume recovery should result in membrane depolarization. This has not been demonstrated.

It has become clear that ion uptake cannot continue when Cl− in the bathing medium is replaced by IDA (Figs. 8A and 9A) or when K+ is replaced by TEA+ (Figs. 8B and 9B). Therefore, K+ and Cl− influxes are mutually dependent. The exact mechanism for this mutual regulation is not clear. To understand this regulation, it would be important to clarify whether Cl− uptake is actually mediated by a Cl−/H+ symporter or by a different transport mechanism.

During the response induced by a blue-light pulse, the primary photochemical reaction and subsequent cellular reactions would decay with time. This can explain the transition from the shrinking to the recovery phase. For the corresponding transition during continuous stimulation, however, some additional mechanism must be considered. In theory, the volume recovery can be achieved by enhancement of the ion uptake activity without a change in the ion efflux property. In this case, it is expected that protoplasts continue to shrink for a longer period when ion uptake is inhibited. The data shown in Figure 9 indicated that protoplasts stop shrinking similarly to the controls even if ion uptake cannot take place. Therefore, it seems that the volume recovery during continuous stimulation is not caused by enhanced activity of ion uptake but rather by cessation of the blue-light-induced ion efflux. This agrees with the view that the volume recovery represents a sensory adaptation mechanism that resides within or close to the photoreceptor system (Wang and Iino, 1997).

Roles of Phytochrome

The results obtained using phyA, phyB, and phyAphyB mutants (Figs. 3 and 5) have substantiated the conclusion that Pfr is required for the full expression of CRY1-mediated responses (Casal and Boccaladro 1995; Ahmad and Cashmore, 1997). The results shown in Figure 6 have demonstrated for the first time, to our knowledge, that Pfr is required in advance of blue-light perception. As far as the protoplast shrinking response to pulse stimulation is concerned, the presence of Pfr during and after blue-light perception is not required for blue-light responsiveness. It has also become apparent that phytochrome species other than phytochromes A and B (Mathews and Scharrock, 1997) do not make any significant contribution.

The phytochrome requirement for the CRY1-mediated growth inhibition has been shown by providing a red-light pulse (or a far-red-light pulse as a control) after blue-light treatment (Casal and Boccaladro, 1995; Ahmad and Cashmore, 1997). In contrast to our data and conclusions, it has been implied that Pfr is required after the step of blue-light perception. The previous data, however, do not necessarily demonstrate this. In the experiments of Ahmad and Cashmore (1997), the blue-light pulse and the immediately subsequent pulse of red light were provided hourly. Therefore, it is probable that the Pfr produced by the red light given after a blue-light pulse brought about the responsiveness to the next blue-light pulse. Casal and Boccaladro (1995) repeated light treatments daily. The stable Pfr (perhaps Pfr of phytochrome B) produced by the preceding red-light pulse could possibly persist, at least to some extent, during the long, dark interval to permit some responsiveness to the next blue-light treatment. Furthermore, because the duration of each blue-light treatment was relatively long (3 h), the Pfr (perhaps Pfr of phytochrome A) produced by blue light itself could probably act to bring about some blue-light responsiveness during the blue-light treatment.

Based on the data shown in Figure 6, it has been deduced that the hypothetical component X, an immediate component necessary for the blue-light responsiveness, is produced in a relatively short period (about 15 min) after a lag of about 15 min from the occurrence of Pfr. Such kinetics may suggest an involvement of Pfr-induced gene expression for the production of X. It has been indicated further that X disappears with a similar lag and over a similar time period. These kinetics imply that X and the intermediate components produced by Pfr have relatively short lifetimes. It is expected that the half-life of X is not longer than several minutes. Ahmad and Cashmore (1997) found a normal level of CRY1 protein in a phyAphyB mutant. Therefore, it seems unlikely that X is the photoreceptor itself. It is not excluded, however, that X is a component, such as a chromophore, that attaches to CRY1 for its completion as a photoreceptor.

An increasing body of evidence now indicates that the occurrence of blue-light-dependent phototropism of higher plants is strictly under phytochrome regulation. In maize coleoptiles the time-dependent phototropism requires the presence of Pfr before it becomes inducible with blue light (Liu and Iino, 1997). Use of phyA and phyB mutants and phytochrome A- and B-overexpressing transgenic strains of Arabidopsis have shown that the phototropic fluence-response relationship is greatly modified by the level of either phytochrome A or B (Janoudi et al., 1997). Furthermore, the first pulse-induced positive phototropism and time-dependent phototropism identified in classical ways (Iino, 1990) could not be potentialized at all by red-light pretreatment in the phyAphyB mutant of Arabidopsis (Liu and Iino, 1997), although this mutant may show a slight phototropic response to continuous blue light (Hangarter, 1997). Therefore, Arabidopsis appears to require the presence of Pfr, or a component generated by Pfr, before it can respond to blue light to express phototropism.

It is interesting that both phototropism and blue-light-dependent growth inhibition show a similar dependence on phytochrome. Physiological and genetic evidence have indicated that the two responses are mediated by distinct photoreceptors (Iino, 1990; Liscum et al., 1992; Cosgrove, 1994; Liscum and Briggs, 1995). It is tempting to speculate that, although these photoreceptors are encoded by different genes, they share the same chromophore(s) and that the biosynthesis of this chromophore is under phytochrome control.

Phytochrome-mediated swelling of protoplasts has been described for protoplasts from cereal leaves (Blakeley et al., 1987; Bossen et al., 1988; Chung et al., 1988) and mung bean hypocotyls (Long et al., 1995). The swelling of Arabidopsis protoplasts observed under background red light was greatly impaired by phyAphyB mutations (Fig. 2, E and J), providing further evidence for the occurrence of such a phytochrome-mediated swelling response. As in the case of the volume recovery after the blue-light-induced shrinkage, Arabidopsis protoplasts appeared to swell by taking up K+ and Cl− from the bathing medium with a contribution of the proton motive force. The data shown in Figure 8C suggested that Arabidopsis protoplasts swell in the absence of external Ca2+. This observation should be clarified by further study, because previous results (Bossen et al., 1988) indicated that external Ca2+ is required for the response. Since a slight swelling was observed in phyAphyB protoplasts (Fig. 2, E and J), a contribution of phytochrome species other than phytochrome A and B to the swelling response is not ruled out.

It was indicated that phytochrome B contributes more than phytochrome A for the establishment of blue-light responsiveness. This is to be expected because we adapted the plants and protoplasts to continuous red light, under which most of phytochrome A would be lost. It was surprising to find that phytochrome A contributed more than phytochrome B to the swelling response. A very small amount of phytochrome A, probably present in the red-light-adapted plants (Abe et al., 1985), must be responsible for this response. It is interesting that phytochromes A and B show different effectiveness in two responses within the same cell.

Concluding Remarks

The fact that the majority of the protoplasts from maize coleoptiles (Wang and Iino, 1997) and Arabidopsis hypocotyls (present study) shrink in response to blue light suggests that the turgor of the most cells constituting these organs is reduced by blue light. Efforts made to date have not uncovered such a blue-light-induced turgor decrease (Cosgrove, 1994). Our results should, however, warrant further attempts.

Even if the turgor decreases in response to blue light, this cannot be a direct cause of the growth inhibition, which requires changes in the mechanical property of the cell wall. It remains to be investigated how the activation of anion channels (and possibly also of outward-rectifying cation channels) results in growth inhibition. We have obtained evidence that Cl− is taken up by a Cl−/H+ symporter during recovery of the protoplast volume. Alkalization of the cell wall expected to occur during such Cl− uptake may be responsible for the growth inhibition (Cho and Spalding, 1996). At the moment, however, this explanation seems unlikely, because growth is maximally inhibited by blue light before the time at which the volume recovery was found to begin (for growth data, see Cosgrove, 1994; Wang and Iino, 1997). The plant cell may sense a turgor decrease for the induction of growth inhibition. This possibility does not receive straightforward support, because the growth of Arabidopsis hypocotyls is inhibited by red light (Koorneef et al., 1980) although their protoplasts swell in response to red light.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Akira Nagatani for providing the seeds of Arabidopsis mutants phyA-201, phyB-5, and phyA-201/phyB-5, and Dr. Yoshiji Okazaki for the measurement of the osmolality of our incubation medium. We also thank Drs. Yutaka Tarui, Chiyomi Uematsu, Yujun Liu, and Y. Okazaki for discussion and encouragement during the course of this study.

Abbreviations:

- CRY1

chryptochrome 1

- IDA

iminodiacetic acid

- NPPB

5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)-benzoic acid

- TEA

tetraethylammonium

Footnotes

This work was supported by a Monbusho's grant-in-aid for the Japan Society for Promotion of Science (JSPS) fellows. X.W. was the recipient of a JSPS postdoctoral fellowship.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abe H, Yamamoto KT, Nagatani A, Furuya M. Characterization of green tissue-specific phytochrome isolated immunochemically from pea seedlings. Plant Cell Physiol. 1985;26:1387–1399. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M, Cashmore AR. HY4 gene of A. thaliana encodes a protein with characteristics of a blue-light photoreceptor. Nature. 1993;366:162–166. doi: 10.1038/366162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M, Cashmore AR. The blue-light receptor cryptochrome 1 shows functional dependence on phytochrome A or phytochrome B in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1997;11:421–427. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.11030421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodeo G, Srivastava A, Zeiger E. Vanadate inhibits blue light-stimulated swelling of Vicia guard cell protoplasts. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:1567–1570. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.3.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilby MJ, Walker NA. Chloride transport in Chara. I. Kinetics and current-voltage curves for a probable proton symport. J Exp Bot. 1981;32:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Blakeley SD, Thomas B, Hall JL. The role of microsomal ATPase activity in light-induced protoplast swelling in wheat. J Plant Physiol. 1987;127:187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Bossen ME, Dassen HHA, Kendrick RE, Vredenberg WJ. The role of calcium ions in phytochrome-controlled swelling of etiolated wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) protoplasts. Planta. 1988;174:94–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00394879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AM. Functional bases for interpreting amino acid sequences of voltage-dependent K+ channels. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1993;22:173–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.22.060193.001133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casal JJ, Boccalandro H. Co-action between phytochrome B and HY4 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 1995;197:213–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00202639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho MH, Spalding EP. An anion channel in Arabidopsis hypocotyls activated by blue light. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8134–8138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.8134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CH, Lim S-U, Song P-S, Berlin JD, Goodin JR. Swelling of etiolated oat protoplasts induced by phytochrome, cAMP and gibberellic acid: a kinetic study. Plant Cell Physiol. 1988;29:855–860. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Rapid suppression of growth by blue light. Occurrence, time course, and general characteristics. Plant Physiol. 1981;67:584–590. doi: 10.1104/pp.67.3.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Photomodulation of growth. In: Kendrick RE, Kronenberg GHM, editors. Photomorphogenesis in Plants. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1994. pp. 631–658. [Google Scholar]

- Elzenga JTM, Van Volkenburgh E. Characterization of ion channels in plasma membrane of epidermal cells of expanding pea (Pisum sativum arg) leaves. J Membr Biol. 1994;137:227–235. doi: 10.1007/BF00232591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felle HH. The H+/Cl− symporter in root-hair cells of Sinapis alba. An electrophysiological study using ion-selective microelectrodes. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1131–1136. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.3.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher SR, Leonard RT. Effect of vanadate, molybdate, and azide on membrane-associated ATPase and soluble phosphatase activities of corn roots. Plant Physiol. 1982;70:1335–1340. doi: 10.1104/pp.70.5.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangarter RP. Gravity, light and plant form. Plant Cell Environ. 1997;20:796–800. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1997.d01-124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich R, Busch H, Raschke K. Ca2+ and nucleotide dependent regulation of voltage dependent anion channels in the plasma membrane of guard cells. EMBO J. 1990;9:3889–3892. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoi S, Iino M, Shimazaki K. Outward-rectifying K+ channels in stomatal guard cell protoplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1988;29:907–911. [Google Scholar]

- Iino M. Phototropism: mechanisms and ecological implications. Plant Cell Environ. 1990;13:633–650. [Google Scholar]

- Janoudi A, Gordon WR, Wagner D, Quail P, Poff KL. Multiple phytochromes are involved in red-light-induced en-hancement of first-positive phototropism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:975–979. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.3.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kigel J, Cosgrove DJ. Photoinhibition of stem elongation by blue and red light. Effects on hydraulic and cell wall properties. Plant Physiol. 1991;95:1049–1056. doi: 10.1104/pp.95.4.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M, Rolff E, Spruit JP. Genetic control of light-inhibited hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Z Pflanzenphysiol. 1980;100:147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski MJ, Briggs WR. Regulation of pea epicotyl elongation by blue light. Fluence-response relationships and growth distribution. Plant Physiol. 1988;89:293–298. doi: 10.1104/pp.89.1.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BD, Karlin-Neumann G, Davis RW, Spalding EP. Ca2+-activated anion channels and membrane depolarization induced by blue light and cold in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:1327–1334. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.4.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Ahmad M, Gordon D, Cashmore AR. Expression of an Arabidopsis cryptochrome gene in transgenic tobacco results in hypersensitivity to blue, UV-A, and green light. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995a;92:8423–8427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Robertson DE, Ahmad M, Raibekas AA, Jorns MS, Dutton PL, Cashmore AR. Association of flavin adenine dinucleotide with the Arabidopsis blue light receptor CRY1. Science. 1995b;269:968–970. doi: 10.1126/science.7638620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liscum E, Briggs WR. Mutations in the NPH1 locus of Arabidopsis disrupt the perception of phototropic stimuli. Plant Cell. 1995;7:473–485. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.4.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liscum E, Young JC, Poff KL, Hangarter RP. Genetic separation of phototropism and blue light inhibition of stem elongation. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:267–271. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.1.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YJ, Iino M. Effect of red light on the fluence-response relationship for pulse-induced phototropism of maize coleoptiles. Plant Cell Environ. 1996a;19:609–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1996.tb00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YJ, Iino M. Phytochrome is required for the occurrence of time-dependent phototropism in maize coleoptiles. Plant Cell Environ. 1996b;19:1379–1388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1996.tb00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YJ, Iino M. Dependence on phytochromes A and B of phototropic responsiveness in Arabidopsis hypocotyls (abstract no. 1462) Plant Physiol. 1997;114:S-281. [Google Scholar]

- Long C, Wang X, Pan R. The role of calcium ions in red light-induced swelling of mung bean protoplasts. Chinese Sci Bull. 1995;40:248–250. [Google Scholar]

- Marten I, Zeilinger C, Redhead C, Landry DW, Al-Awqati Q, Hedrich R. Identification and modulation of a voltage-dependent anion channel in the plasma membrane of guard cells by high-affinity ligands. EMBO J. 1992;11:3569–3575. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews S, Sharrock RA. Phytochrome gene diversity. Plant Cell Environ. 1997;20:666–671. [Google Scholar]

- Nagatani A, Reed JW, Chory J. Isolation and initial characterization of Arabidopsis mutants that are deficient in phytochrome A. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:269–277. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.1.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okihara K, Ohkawa T, Tsutsui I, Kasai M. A Ca2+- and voltage-dependent Cl−-sensitive anion channel in the Chara plasmalemma: a patch-clamp study. Plant Cell Physiol. 1991;32:593–601. [Google Scholar]

- Reed JW, Nagatani A, Elich TD, Fagan M, Chory J. Phytochrome A and phytochrome B have overlapping but distinct function in Arabidopsis development. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:1139–1149. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.4.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SK, Tester M. Inward and outward K+-selective currents in the plasma membrane of protoplasts from maize root cortex and stele. Plant J. 1995;8:811–825. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Hagiwara S. Cytosolic calcium regulates ion channels in the plasma membrane of Vicia faba guard cells. Nature. 1989;338:427–430. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Raschke K, Neher E. Voltage dependence of K+ channels in guard cell protoplasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4108–4112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimmen T, Tazawa M. Activation of K+-channel in membrane excitation of Nitella axilliformis. Plant Cell Physiol. 1983;24:1511–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Spalding EP, Cosgrove DJ. Large plasma-membrane depolarization precedes rapid blue-light-induced growth inhibition in cucumber. Planta. 1989;178:407–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalding EP, Cosgrove DJ. Mechanism of blue-light-induced plasma-membrane depolarization in etiolated cucumber hypocotyls. Planta. 1992;188:199–205. doi: 10.1007/BF00216814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckel H, Takeda K. Calcium-activated, voltage-dependent, non-selective cation currents in endosperm plasma membrane from higher plants. Proc Royal Soc London B. 1989;237:213–231. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Iino M. Blue light-induced shrinking of protoplasts from maize coleoptiles and its relationship to coleoptile growth. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:1009–1020. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.3.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelam GC, Devlin PF. Roles of different phytochromes in Arabidopsis photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell Environ. 1997;20:752–758. [Google Scholar]

- Widholm JM. The use of fluorescein diacetate and phenosafaranine for determining viability of cultured plant cells. Stain Technol. 1972;47:189–194. doi: 10.3109/10520297209116483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyn Jones RG, Brady CJ, Speirs J (1979) Ionic and osmotic relationships in plant cells. In DL Laidman, RG Wyn Jones, eds, Recent Advances in the Biochemistry of Cereals. Academic Press, New York, pp 63–103