Abstract

Objective To quantify the effect of opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV transmission among people who inject drugs.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective published and unpublished observational studies.

Data sources Search of Medline, Embase, PsychINFO, and the Cochrane Library from the earliest year to 2011 without language restriction.

Review methods We selected studies that directly assessed the impact of opiate substitution treatment in relation to incidence of HIV and studies that assessed incidence of HIV in people who inject drugs and that might have collected data regarding exposure to opiate substitution treatment but not have reported it. Authors of these studies were contacted. Data were extracted by two reviewers and pooled in a meta-analysis with a random effects model.

Results Twelve published studies that examined the impact of opiate substitution treatment on HIV transmission met criteria for inclusion, and unpublished data were obtained from three additional studies. All included studies examined methadone maintenance treatment. Data from nine of these studies could be pooled, including 819 incident HIV infections over 23 608 person years of follow-up. Opiate substitution treatment was associated with a 54% reduction in risk of HIV infection among people who inject drugs (rate ratio 0.46, 95% confidence interval 0.32 to 0.67; P<0.001). There was evidence of heterogeneity between studies (I2=60%, χ2=20.12, P=0.010), which could not be explained by geographical region, site of recruitment, or the provision of incentives. There was weak evidence for greater benefit associated with longer duration of exposure to opiate substitution treatment.

Conclusion Opiate substitution treatment provided as maintenance therapy is associated with a reduction in the risk of HIV infection among people who inject drugs. These findings, however, could reflect comparatively high levels of motivation to change behaviour and reduce injecting risk behaviour among people who inject drugs who are receiving opiate substitution treatment.

Introduction

Use of injected drugs is a major risk factor for the acquisition and transmission of HIV, and about 5-10% of HIV infections are attributable to injecting drug use worldwide.1 Transmission of HIV between people who inject drugs is predominantly a result of the sharing of contaminated injecting equipment, but also sexual transmission, both of which are influenced by wider structural and environmental factors such as housing, patterns of drug use, commercial sex work, and the availability and nature of interventions aimed at reducing harm.2 3 4

Estimates of the prevalence of HIV among people who inject drugs are over 40% in many parts of the world, and around three million (range 0.8-6.6 million) of the 16 million (range 11-21 million) people who inject drugs worldwide could be HIV positive.5 6 Although HIV incidence has fallen or remains low among people who inject drugs in North America, Australasia, and parts of Western Europe,3 7 8 9 injecting drug use has driven recent outbreaks in Europe,10 as well as epidemics in cities in the United States, United Kingdom, Thailand, Russia, India, China, Vietnam, and Estonia,4 11 12 13 14 and HIV incidence is increasing in parts of Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia, where the burden of HIV among people who inject drugs is comparatively higher.5 6 15

Methadone, an opioid agonist, and buprenorphine, a partial agonist, are the main pharmacological drugs prescribed for people dependent on opiates, and they were included in the list of World Health Organization (WHO) essential medicines in 2005. They are provided in oral, film, or sublingual form and are often prescribed as opiate substitution treatments for people with established opiate dependence.16 In addition to reducing craving for, and use of, heroin or other illicit opiates, there is good evidence to suggest that opiate substitution treatment reduces drug related mortality, offending, and injection risk behaviour, and that it improves adherence to antiretroviral treatment for those with HIV.17 18 19 20 21 22 Methadone and buprenorphine can also be prescribed in tapering doses for detoxification.

Opiate substitution treatment has been implemented in 70 countries, but remains unavailable in 66, and in several countries detoxification or residential rehabilitation is the primary mode of treatment.2 23 Although coverage of opiate substitution treatment is being expanded in some countries, such as Ukraine, India, and China,24 25 26 intervention at a regional and national level remains poor in many countries, including those with a high burden of HIV among people who inject drugs.23

Previous reviews have generally concluded that reductions in the frequency of injection and sharing of injecting equipment that are associated with exposure to opiate substitution treatment translate into reductions in cases of HIV infection.21 The conclusions of these reviews, including a recent Cochrane systematic review, however, have been based on a small number of primary studies with limited sample size.19 21 27 Critically, no pooled analysis has been carried out to date, and as such, there remains no quantitative estimate of the effect of opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV transmission.

We carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished observational studies to quantify the association between opiate substitution treatment and risk of HIV transmission among people who inject drugs.

Methods

Primary and secondary objectives

Our primary objective was to assess the impact of opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV incidence among people who inject drugs. Secondary research objectives were to examine the effect of variables including mode of treatment (such as methadone or buprenorphine; continuous or interrupted treatment; detoxification treatment); duration of treatment; geographical region; study setting (such as drug treatment clinic or other setting); and characteristics of participants (such as age, sex).

Search strategies

We carried out two separate systematic searches to identify relevant studies. The first search identified studies that directly examined the impact of opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV incidence. We searched Medline, Embase, and PsycINFO from the earliest possible year to October 2011 using the Ovid platform with no limit to language and searched the Cochrane Library up to 2011. Reference lists of robust literature reviews were assessed to identify relevant studies. Briefly, terms included those relating to HIV infection or transmission; intravenous substance use, misuse, addiction, or dependence; and substitution, maintenance, methadone or buprenorphine treatment (table A in appendix 1). The search included exploded MESH terms and text words to enhance retrieval of relevant studies.

Secondly, we searched Medline, Embase, and PsycINFO up to May 2011 to identify prospective cohort studies that reported HIV incidence in people who inject drugs. These studies were examined to identify whether they reported the impact of opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV transmission in secondary analyses in the full text (but not in the title or abstract), and, if so, the studies were included. Authors of studies of HIV incidence in people who inject drugs that did not report opiate substitution treatment as a covariate were contacted in case data regarding exposure to had been collected but not yet published. The search strategy used similar terms to the first search but was limited to longitudinal or cohort studies (table A in appendix 1).

Study selection

After export of all identified studies to Reference Manager 12 and removal of duplicates, two reviewers screened titles and abstracts and disagreements were resolved by discussion. Two reviewers screened full text copies of relevant articles to determine whether they met eligibility criteria for inclusion and suitability for inclusion in the meta-analysis or for contact of study authors. Full text papers in languages other than English were translated by individuals fluent in those languages or, for one paper, by Google translate.

Data extraction and analysis

Two authors used piloted forms to extract data from studies, including details of studies (such as year of publication, country, study design); study characteristics (such as inclusion criteria, site of recruitment or study); intervention (such as methadone or buprenorphine maintenance treatment; continuous versus interrupted treatment; detoxification treatment only); and intervention effect (seroconversions, follow-up period, incidence rates, or unadjusted and adjusted measures of effect, including incidence rate ratio or hazard ratio, and confounders used in adjusted estimates).

Eligibility criteria

We included studies in this review if they were randomised controlled trials, prospective cohort studies, or case-control studies that directly examined the impact of opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV incidence in people who inject drugs; or if they prospectively examined HIV incidence in people who inject drugs but did not report data regarding the impact of opiate substitution treatment. We included studies that assessed the impact of continuous or interrupted opiate substitution treatment; current, recent, or previous opiate substitution treatment; or opiate substitution treatment at baseline. We excluded cross sectional or serial cross sectional studies and those studies identifying the outcome from retrospective analysis of routine medical records to identify outcome or exposure to opiate substitution treatment (in the latter case they were considered subject to selection bias because of different motivations and characteristics of individuals undergoing voluntary testing). We also excluded studies carried out in prisons. Studies were included only if data relating to opiate substitution treatment were reported in opiate injectors. We excluded studies that reported fewer than two seroconversions during follow-up to ensure that estimates generated were sufficiently precise. Participants of the included studies were people who inject opiates with no restriction around age, sex, ethnic group, or socioeconomic group. Duplicate papers from the same cohort study were grouped, and studies with the largest number of seroconversions or that reported adjusted and unadjusted analyses, or both, were selected.

Assessment of risk of bias

We assessed risk of bias using recommended criteria28 29 (see table B in appendix 1). Studies were judged to be at low, high, or unclear risk of bias on the basis of what was reported in the study for each of these domains. Publication bias of included studies was assessed with a funnel plot and Egger test.30 31

Summary measures and synthesis of results

We used Poisson regression to obtain incidence rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals from raw data in unpublished datasets provided (A Judd, 2012, and S Deren, 2012) and where information regarding seroconversion and person years of follow-up was provided in published studies. When only effect estimates were reported, we directly extracted unadjusted and adjusted estimates if they were reported as odds ratio, incidence rate ratio, or hazard ratio with 95% confidence intervals. As the incidence of HIV in included studies was low (<10/100 person years), effect estimates that were reported as odds ratios were extracted directly as it was assumed that the odds ratio was a reasonable approximate of the relative risk.32

Studies that reported data relating to exposure to opiate substitution treatment and HIV seroconversion were pooled for meta-analysis if data were provided regarding HIV seroconversions, person years of follow-up, and exposure to opiate substitution treatment; or an effect estimate of the impact of opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV incidence with 95% confidence intervals. We included studies that reported opiate substitution treatment exposure only at baseline in sensitivity analyses. We excluded studies that examined methadone maintenance treatment compared with methadone detoxification treatment from the primary meta-analysis but included them in separate subgroup analyses.

As we expected heterogeneity between studies, we used a random effects meta-analysis for the primary analyses, allowing for heterogeneity between and within studies. Adjusted and unadjusted effect estimates were pooled in separate meta-analyses. We examined heterogeneity with the I2 statistic and χ2test and explored reasons for heterogeneity using univariable random effects meta-regression (using the “metareg” command)33 to compare subgroups by geographical region of study; the provision of monetary incentives; site of recruitment; the examined duration of exposure to opiate substitution treatment; and the percentage of female participants or individuals from ethnic minorities.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to include studies that assessed the impact of exposure to methadone maintenance treatment at baseline only; the impact of inclusion only of studies at lower risk of bias (that is, scoring as low risk across three or fewer domains with the risk of bias tool); including only studies that measured an incidence rate ratio; and the impact of excluding those that did not adjust for confounders.

All analyses were carried out with STATA version 11.

Results

Study selection

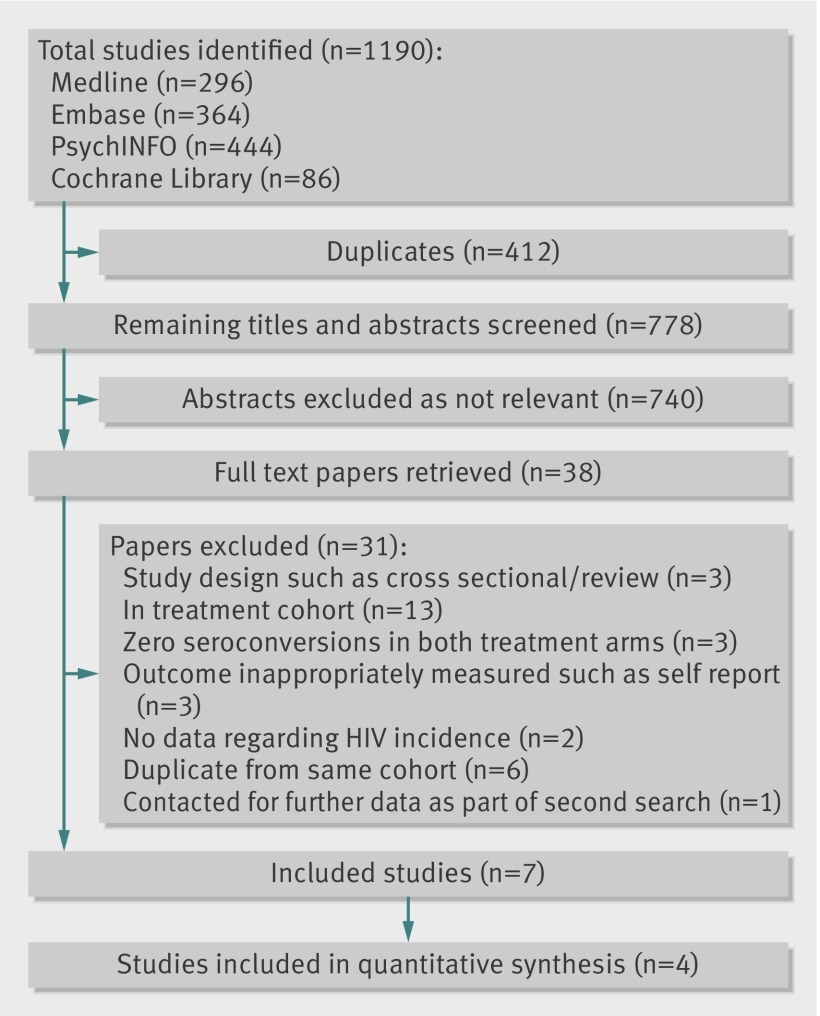

Figures 1 and 2 show the number of studies identified, reviewed, and selected and the reasons for exclusion. The first search enabled the identification of seven eligible studies, four of which included data that could be included in the quantitative synthesis (fig 1). Three studies were excluded on the basis that no HIV seroconversions were identified in either treatment arm.34 35 36

Fig 1 Selection of studies directly investigating impact of opiate substitution treatment on HIV transmission

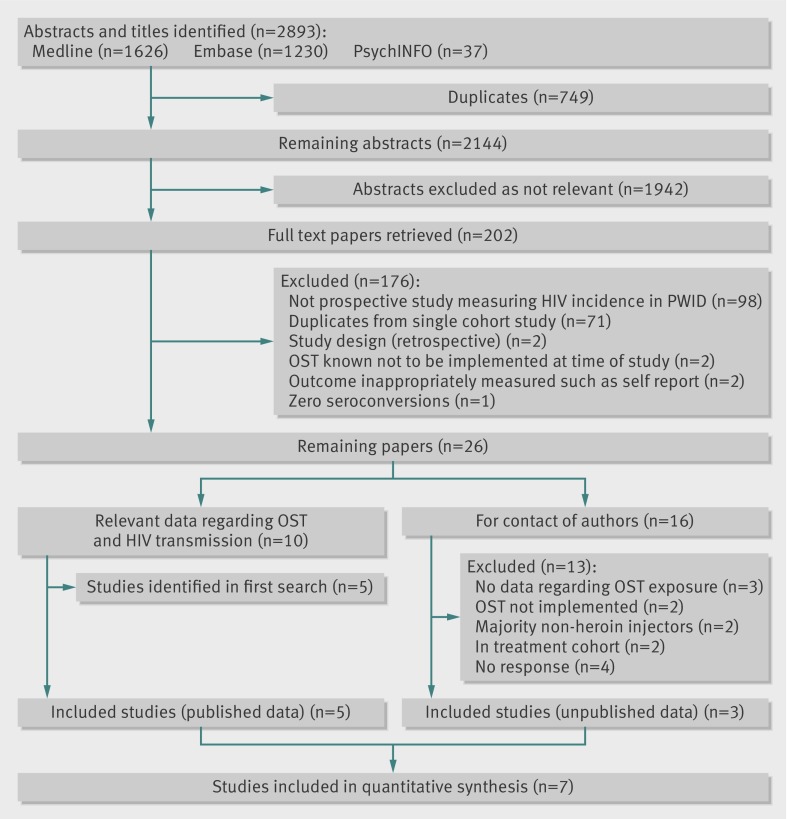

Fig 2 Selection of prospective cohort studies relating to HIV incidence in people who inject drugs. Of seven identified, two were included in sensitivity or subgroup analyses only

The second search (fig 2) enabled identification and inclusion of 10 eligible papers that included data directly relating to the impact of exposure to opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV transmission, of which five were newly identified studies not identified in the first search.8 11 37 38 39 In addition, we identified 16 eligible prospective studies that measured HIV incidence among people who inject drugs and contacted authors of these articles. Of these, unpublished data were obtained from cohort studies in London, UK (A Judd, personal communication, 2012); Montreal, Canada (J Bruneau, personal communication, 2012); and a dual site study of Puerto Rican injecting drug users in Bayamon, Puerto Rico, and East Harlem, New York City (S Deren, personal communication, 2012). Overall, eight studies were included from this search, seven of which could be included in the quantitative synthesis (fig 2).

In the second search (fig 2), we excluded one study because no HIV seroconversions occurred among participants,40 and two studies that constructed a retrospective cohort based on clinical records of voluntary testing for hepatitis C virus and HIV.41 42 Seventy one studies were duplicates from the same cohort (particularly the Amsterdam Cohort Study; Vancouver Injection Drug User Study; and AIDS Linked to Intravenous Experience (ALIVE) cohort study).

We therefore included 12 published studies8 11 17 37 38 39 43 44 45 46 47 48 and the three unpublished studies, comprising 1016 incident HIV infections and over 26 738 person years of follow-up.

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the 15 included studies undertaken in the US (including unpublished data from S Deren, 2012),8 39 43 44 46 Canada (including unpublished data from J Bruneau, 2012),37 UK (unpublished data from A Judd, 2012), the Netherlands,45 Austria,47 Italy,48 Thailand,11 17 Puerto Rico (unpublished data from S Deren), and China.38 All of the included studies reported the impact of methadone maintenance treatment. The included studies were variable in terms of sample size (range 80-2546), method of recruitment (drug treatment clinic (six studies); community settings and outreach (six studies); drug treatment clinics and community settings (three studies); duration of follow-up (range 1-20 years), and year of publication (1992-2009).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies of opiate substitution treatment (OST) and impact on HIV transmission

| Study | Follow-up | Study type | Recruitment site/method | Inclusion criteria | Sample size* | HIV incidence (95% CI)† | Intervention | Impact of treatment on HIV seroconversion | Confounders included in adjusted analyses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect measure | Effect estimate (95% CI) | |||||||||

| Studies included in meta-analysis | ||||||||||

| Bruneau, 2012 (unpublished)‡ Montreal Canada | 1992-2008 | Cohort | Street, word of mouth, community programmes | Age >18; injected for past 6 months | 1374 | 2.57 (2.0 to 3.2) | MMT in previous 6 months (yes/no) | HR | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.7), adjusted 0.3 (0.1 to 1.3) | Age, sex, housing, cocaine use, heroin use, sharing, booting, having sex with person known to be HIV positive, period of recruitment |

| Chitwood, 1995, Miami, US39 | 1988-91 | Nested case-control | Drug treatment programme; street | Cases: participants testing positive for HIV infection 1988-1991. Control: participants testing negative for HIV infection within 2 week period before date of first positive test of case | 97 | 2.1 | Methadone treatment in year before seroconversion or last negative test date (yes/no) | OR | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.9), adjusted 0.7 (0.2 to 2.8) | Age, sex, ethnicity |

| Deren, 2012 (unpublished), Bayamon, Puerto Rico | 1998-2002 | Cohort | Targeted sampling based on ethnographic mapping | Age ≥18, injected drugs in previous 30 days, use of heroin in previous 48 hours, self identification as Puerto Rican | 143 | 3.7 (2.3 to 6.1) | MMT at baseline (yes/no) | IRR | 0.2 (0.0 to 3.5) | |

| Deren, 2012 (unpublished), New York City, US | As above | As above | As above | 154 | 0.83 (0.3 to 2.2) | MMT at baseline (yes/no) | IRR | 0.3 (0.0 to 2.4) | ||

| Judd, 2012 (unpublished), London, UK | 2001-02 | Cohort | Community, such as needle and syringe exchange programmes or street settings | Age <30; injecting ≤6 years; injected previous 4 weeks; address for follow-up | 272 | 2.9 | OST for ≥6 months in last year (yes/no) | IRR | 0.8 (0.2 to 3.2), adjusted 0.8 (0.2 to 3.2) | Crack injection, homelessness |

| Kerr, 2006, Vancouver, Canada37 | 1996-2002 | Cohort | Street outreach; self referral | Injected drugs in past month; resident in Vancouver region | 1013 | 3.2 (2.6 to 3.7) | Methadone treatment in previous 6 months (yes/no) | RH | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.1), adjusted 0.8 (0.5 to 1.4) | Sex, aboriginal ethnicity, frequent cocaine injection, frequent heroin injection, requiring help injecting, binge drug use, having HIV positive sexual partner‡ |

| Metzger, 1993, Philadelphia44 | 1989-91 | Cohort | Outpatient methadone programme; community outreach | MMT: methadone programme participation; no MMT: >18 years; history of intravenous opiate use (≥3/week); no drug treatment in previous 10 months | 185 | 3.0 in treatment; 10.7 out of treatment | MMT over 18 month period (yes/no) | OR | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.5), adjusted 0.2 (0.1 to 0.6) | Age, sex, ethnicity, needle sharing |

| Nelson, 2002, Baltimore, US8 | 1988-98 | Cohort | Community outreach | Αge ≥18; free from AIDS at baseline; injected drugs in past 10 years | 1846 | 3.1 (2.8 to 3.5) | MMT in previous 6 mo (yes/no) | IRR | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.9) | |

| Suntharasamai, 2009, Bangkok, Thailand17 | 1999-2003 | Nested cohort in RCT | Drug treatment clinics and community | HIV negative; history of injected drug use in previous year; age 20-60; informed consent | 2546 | 3.4 (3.0 to 3.9) | MMT in previous 6 months (yes/no) | HR | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.0), adjusted 0.60 (0.4 to 0.8) | Incarceration, injecting drugs, injecting daily, sharing injecting equipment, participation in methadone detoxification programme§ |

| Van den Berg, 2007 Amsterdam, Netherlands45 | 1985-2005 | Cohort | Drug treatment clinics and self referral | History of ever injecting drugs; negative for HIV and/or HCV negative at study entry or at start of injecting drug use | 710 | 1.65 | Any dose of MMT daily in previous 6mo (yes/no) | IRR | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.5) | |

| Vanichseni, 2001, Bangkok, Thailand11 | 1995-98 | Cohort | Drug treatment clinic | History of injected drug use; age 18-50; attendance at Bangkok Metropolitan Administration drug treatment clinics; not known to be HIV seropositive | 1124 | 5.8 (4.8 to 6.8) | MMT or detoxification in previous 4 months (yes/no) | IRR | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) | |

| Williams, 1992, New Haven, US46 | 1992-98 | Cohort | Methadone maintenance programme | History of injected drug use; past/current client of MMT programme; age ≥18 and one of three additional criteria** | 98 | 2.8 | Continuous MMT v interrupted MMT during follow-up | IRR | 0.2 (0.0 to 1.3) | |

| Studies not included in meta-analysis | ||||||||||

| Moss, 1994 San Francisco, US43 | 1985-90 | Cohort | Methadone maintenance/ detoxification programmes; hospital | HIV negative heterosexual people who inject drugs tested at least twice | 681 | 1.9 | ≤12 lifetime months in MMT (yes/no) | HR | 5.1, adjusted 4.0 | Age, sex, ethnicity |

| Ruan, 2007, Xichang City, China38 | 2002-05 | Cohort | Community outreach and peer referral | HIV seronegative; age ≥18; injected of drugs in previous 3 months; willing to provide informed consent | 229 | 2.3 (1.1 to 3.5) | MMT in previous 6 months (yes/no) | — | MMT: 0 sc No MMT: incidence 2.9/100 person years | |

| Serpelloni, 1994, Verona, Italy48 | 1985-91 | Nested case-control | Drug dependency unit | HIV seronegative injecting drug users | 80 | — | No of cycles of MMT; daily dose; time out of treatment (previous 12 months) | — | See footnote†† | |

| Zangerle, 1992, Innsbruck, Austria47 | 1985-90 | Cohort | Drug dependency or AIDS clinic | Injecting drug users attending drug dependency or AIDS clinic of University of Innsbruck | 102 | 5.8 | MMT for ≥2 months duration (yes/no) | — | MMT: 0/43 sc over mean 1.6 year; No MMT: 10/59 sc over mean 1.76 years (incidence 9.6/100 person years) | |

sc=seroconversions; MMT=methadone maintenance treatment; IRR=incidence rate ratio; RH=relative hazard; HR=hazard ratio; OR=odds ratio.

*Size of sample of HIV negative participants in analysis of impact of opiate substitution treatment on HIV incidence.

†As rate per 100 person years. Incidence relates to entire study period when such an estimate was provided in study.

‡Effect estimate adjusted for all variables significantly associated with time to HIV infection in univariate analyses at P≤0.1, as listed. Variables refer to preceding 6 months

§Effect estimate adjusted for all variables significantly associated with incident HIV infection at P≤0.1 in bivariate analysis, as listed.Variables refer to preceding 6 months.

¶Study participants with “no dependence” were excluded from analysis to calculate this estimate from reported data.

**Additional criteria for study entry included: had participated in 1982-83 study of hepatitis and had identifiable serum sample from that study in serum bank of researchers; had been in methadone programme consistently since 1982; or entered methadone programme between October 1985, and July 1988. Entry into 1982-83 hepatitis study required mild increases in transaminase activity without serological evidence of active hepatitis B infection at time of study (1982-83).

††Lower dose and more time out of treatment associated with increased risk of HIV infection in univariate but not multivariate analyses. Number of cycles of MMT not significantly associated with risk of HIV infection.

Most studies reported the impact of methadone maintenance treatment as one of a range of factors assessed in relation to the risk of HIV infection and most reported an associated lower risk of HIV infection (unpublished data from S Deren and J Bruneau, 2012).8 38 39 45 47 48 Four studies could not be included in the meta-analyses because of the comparisons made or the nature of the data presented (table 1).38 43 47 48 Among these studies, Moss and colleagues reported a lower incidence or risk of HIV among people who inject drugs with more than 12 lifetime months of methadone maintenance treatment compared with those with less than 12 months, and a lower seroconversion rate among those recruited from methadone maintenance treatment programmes compared with those recruited from detoxification programmes or hospital.43 Serpelloni and colleagues reported a lower risk of seroconversion associated with methadone dose and cycles of treatment in univariate but not multivariate analyses.48 Two studies38 47 reported HIV seroconversions among people who inject drugs out of treatment but not among those receiving treatment over follow-up (table 1).

All of the included studies were judged to be at high risk of selection bias and low risk of performance bias and most were at low risk of ascertainment bias. A few studies, however, were at high risk of attrition bias (table 2 and table C in appendix 1) and few adjusted for confounders.

Table 2.

Risk of bias in included studies assessed with criteria drawn from Newcastle-Ottawa scale and EPOC group, adapted for assessment of randomised controlled trials, case-control trials, and prospective observational studies according to criteria recommended by Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Review Group28 29

| Study | Selection bias | Performance bias* | Detection bias† | Attrition bias‡ | Other bias | Ascertainment bias¶ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Comparability of cohorts§ | Selection of non-exposed | Contamination | |||||

| Bruneau et al, unpublished | High | High | Low | Low | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Chitwood, 199539 | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Deren et al, unpublished | High | High | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Judd et al, unpublished | High | High | Low | Low | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Kerr, 200637 | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Metzger, 199344 | High | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Moss, 199443 | High | High | Low | Low | High | High | High | High | High |

| Nelson, 20028 | High | High | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Ruan, 200738 | High | High | Low | Low | High | High | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Serpelloni, 199448 | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Suntharasamai, 200917 | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Van den Berg, 200745 | High | High | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Vanichseni, 200111 | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Williams, 199246 | High | High | Low | Unclear | High | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Zangerle, 199247 | High | High | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Unclear | Low |

*Outcome unlikely to be biased by lacking of blinding.

†Objective outcomes, record linkage.

‡Incomplete outcome data.

§Studies deemed at high risk if there was no matching or no adjustment for most important confounding factors.

¶Ascertainment of exposure.

Primary meta-analysis

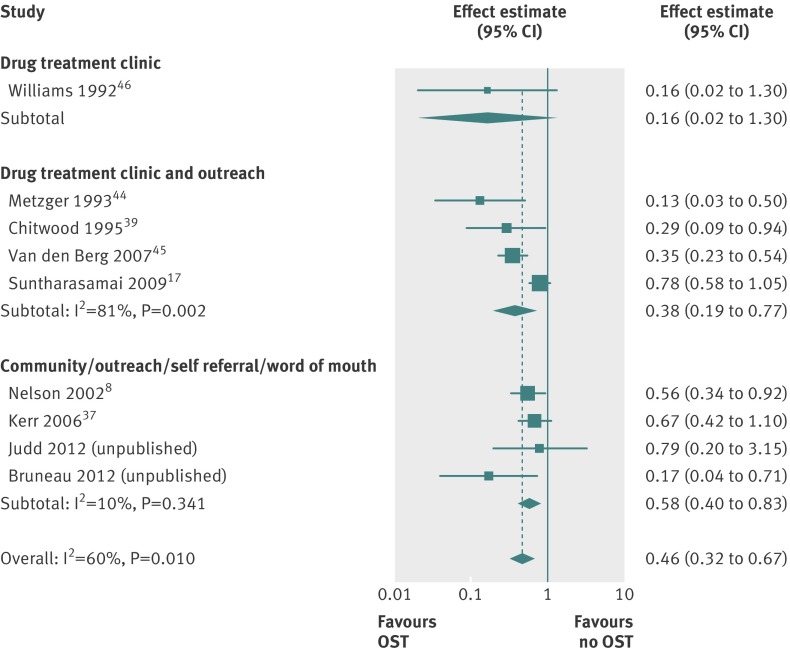

Of the 15 included studies, we were able to pool data from nine to assess the impact of opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV transmission (unpublished data from A Judd and J Bruneau, 2012),8 17 37 39 44 45 46 (two additional studies (unpublished data from S Deren, 2012, and Vanichseni and colleagues11) were included only in sensitivity or subgroup analyses). The nine studies predominantly included men (range among studies 61-93%), with median age ranging from 26 to 39, and the proportion of participants from an ethnic minority group ranging from 15% to 92%. The sample included 819 incident HIV infections over 23 608 person years of follow-up.

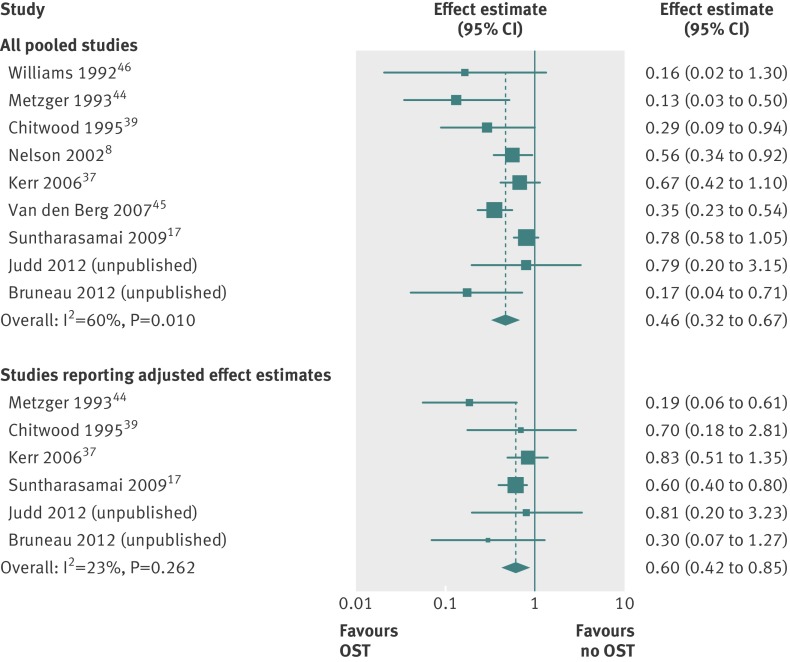

Random effects meta-analysis showed strong evidence that opiate substitution treatment was associated with a 54% reduction in the risk of HIV infection (rate ratio 0.46, 95% confidence interval 0.32 to 0.67; P<0.001), though there was heterogeneity between studies (I2=60%, χ2=20.12; P=0.010) (fig 3). Inclusion of unpublished data regarding the impact of methadone maintenance treatment at baseline (S Deren, 2012) gave a similar estimate of effect (0.45, 0.32 to 0.65; P<0.001; test for heterogeneity I2=52.5%, χ2=21.06; P=0.021; fig A in appendix 2).

Fig 3 Meta-analysis of studies showing impact of opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV transmission in people who inject drugs among all pooled studies and studies reporting only adjusted effect estimates

Pooling of a subset of six studies that adjusted for confounders (including unpublished data from S Deren and J Bruneau, 2012) (see table 1) 17 37 39 44 reduced the sample to 450 incident HIV infections during over 10 064 person years of follow-up and suggested that methadone maintenance treatment was associated with a 40% reduction in risk of incident HIV infection (rate ratio 0.60, 0.42 to 0.85; P=0.004; test for heterogeneity I2=23%, χ2=6.49; P=0.26; fig 3). Furthermore, meta-analysis of a subset of five studies that excluded those at higher risk of bias (including unpublished data from J Bruneau, 2012)17 37 49 also showed effectiveness of opiate substitution treatment (0.61, 0.41 to 0.91; P=0.016 test for heterogeneity: I2=38%, χ2=6.50; P=0.165); while pooling of a subset of studies for which effect estimates were expressed only as incidence rate ratio gave a similar effect (0.53, 0.34 to 0.84; P=0.006; I2=64%, χ2=11.0; P=0.027; data not shown).

As HIV incidence rates varied substantially between the sites (from less than one to more than five cases per 100 person years), we have reported the rate reduction, rather than an absolute measure of effect (the risk difference), which would not be generalisable to other sites.

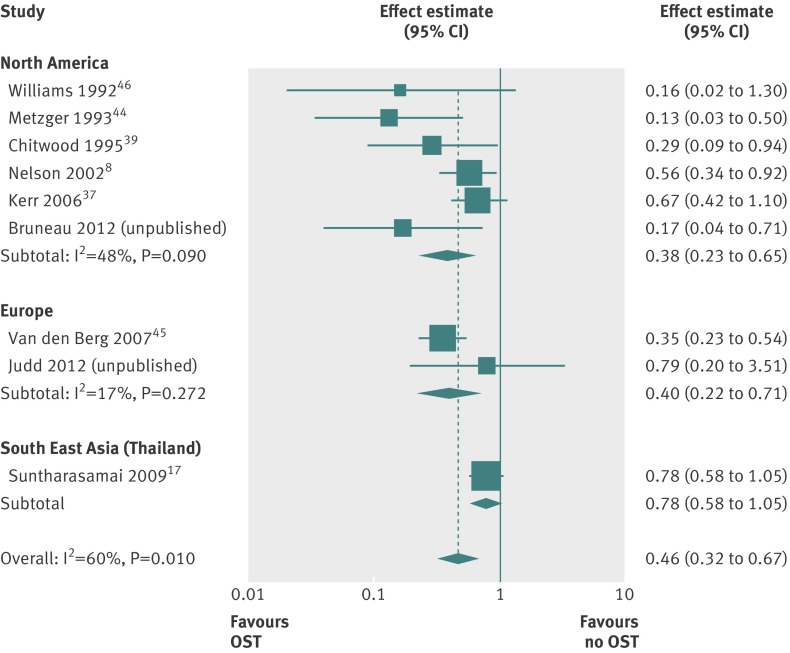

Metaregression analyses

Based on univariable metaregression analyses, we found no evidence that the effectiveness of opiate substitution treatment varied according to geographical region or by site of recruitment (P=0.47 and P=0.59, respectively) (figs 4 and 5; table D in appendix 1). We also found no evidence to suggest that the effect of opiate substitution treatment differed by the provision of incentives to participants (P=0.70; fig B in appendix 2 (top panel)). Though there was weak evidence that longer duration of exposure to opiate substitution treatment could be associated with greater benefit (P=0.18; fig B in appendix 2 (bottom panel)), the confidence intervals around the summary effect estimates were wide and few studies assessed exposure over time periods greater than six months. Lastly, our analyses did not support a differential impact by the proportion of female participants or proportion of participants from ethnic minorities (table D in appendix 1).

Fig 4 Impact of opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV incidence among people who inject drugs by geographical region

Fig 5 Impact of opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV incidence among people who inject drugs by site of recruitment of study participants

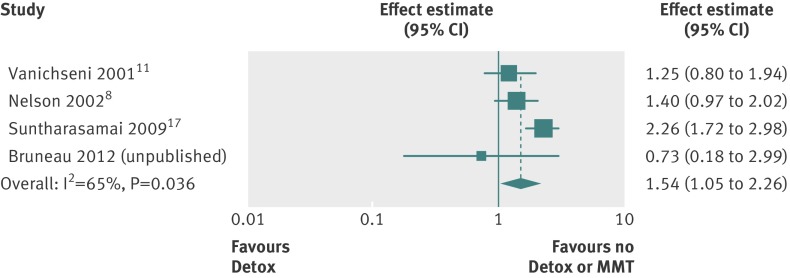

Methadone detoxification treatment

Four studies reported the impact of methadone detoxification treatment, three of which examined detoxification (in the preceding six months) compared with no treatment (unpublished data from J Bruneau, 2012)8 17 and one of which examined 45 day methadone detoxification compared with methadone maintenance treatment in the preceding four months.11 Together the four studies included 687 incident HIV infections in 20 616 person years of follow-up. HIV incidence was reported to be higher among those undergoing detoxification treatment (table 3), and our pooled analysis showed no evidence that detoxification was associated with a decreased risk of HIV infection compared with either no treatment or methadone maintenance treatment (relative risk 1.54, 1.05 to 2.26; P=0.026; n=4 studies; fig 6). The effect was similar when we pooled studies that compared detoxification with no treatment only (1.66, 1.04 to 2.66; P=0.035; n=3 studies).

Table 3.

Data regarding HIV incidence and estimate of effect of methadone detoxification treatment in relation to HIV transmission among people who inject drugs

| Exposure variable | HIV seroconversions/person years | HIV incidence per 100 py (95% CI) | Rate ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanichseni et al 200111 | 45 day detoxification in past 4 months; methadone maintenance treatment | Detox: 106/1730.6; MMT: 24/488.3 | 6.1 (5.0 to 7.4); 4.9 (3.1 to 7.3) | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.8) |

| Nelson et al 20028 | Detoxification in past 6 months (yes/no) | Yes: 33/778; No: 243/8033 | Yes: 4.24*; No: 3.03 | 1.4 (0.97 to 2.02) |

| Suntharasamai et al 200917 | 45-day methadone detoxification in past 6 months (yes/no) | Yes: 89/1666; No: 121/5130 | Yes: 5.3 (4.3-6.6); No: 2.4 (2.0-2.8) | 2.4 (1.8 to 3.3) |

| Bruneau, 2012 (unpublished) | Methadone detoxification in past 6 months (yes/no) | NA | NA | 0.73 (0.18 to 2.99) |

NA=not available.

*95% confidence intervals were not reported.

Fig 6 Meta-analysis of included studies showing impact of detoxification treatment on incident HIV infection among people who inject drugs compared with either no treatment or methadone maintenance treatment

Publication bias

We did not identify studies of small sample size that reported negative effects of opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV transmission in the published literature, although data were obtained from one small unpublished study. There was weak evidence of publication bias (Egger’s bias coefficient −1.82; P=0.052) (fig C in appendix 2).

Discussion

Principal findings

There is evidence from published and unpublished observational studies that opiate substitution treatment is associated with an average 54% reduction in the risk of new HIV infection among people who inject drugs. There is weak evidence to suggest that greater benefit might be associated with longer measured duration of exposure to opiate substitution treatment. All of the eligible studies examined the impact of methadone maintenance treatment, indicating that there are few data regarding the impact of buprenorphine or other forms of non-methadone opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV transmission. We found no evidence that methadone detoxification is associated with a reduction in the risk of HIV transmission.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

To our knowledge this is the first study that synthesises the available evidence and generates a quantitative estimate of the impact of opiate substitution treatment on incidence of HIV. A previous Cochrane systematic review concluded that “available data are limited but it appears that the reductions in risk behaviour related to drug use do translate into actual reductions in cases of HIV infection.”21 Our review identified an additional 11 studies compared with this review and provided a quantitative assessment, including data from an additional 924 HIV seroconversions in over 25 660 additional person years of follow-up. As such, our study extends and strengthens this conclusion, providing the most comprehensive quantitative measure to date of the association between opiate substitution treatment and risk of incident HIV infection.

This was achieved partly by identifying studies that measured HIV incidence among people who inject drugs and that reported the impact of opiate substitution treatment in secondary analyses (and hence did not report the data in the title or abstract), and also by identifying studies that might have collected data relating to opiate substitution treatment but not yet have published the analyses. Three of 16 authors contacted were able to provide unpublished data for inclusion in our study, and nine of the 13 other studies were ineligible for inclusion (because opiate substitution treatment was unavailable when the study was conducted, data regarding exposure to opiate substitution treatment were not collected, all participants received treatment, or the participants were mostly stimulant injectors), while four authors did not respond (table E in appendix 1). We consider it unlikely that obtaining additional data from this small number of additional potential studies would affect our results.

Limitations

Nevertheless, our review has several limitations. All of the studies included were observational studies subject to bias, particularly selection and attrition bias. Randomised controlled trials to assess effectiveness of opiate substitution treatment in relation to HIV transmission are no longer ethical, however, given the range of benefits of this treatment,17 19 20 21 22 so meta-analysis of observational analyses, as conducted here, is required. Nonetheless, the extent to which the studies were representative of all people who inject drugs and are receiving opiate substitution treatment is unclear. The proportion of participants who stopped injecting during opiate substitution treatment might have varied between cohorts. In addition, it is possible that cohorts might under-represent short term injectors and those who have stopped injecting or individuals who have considerably reduced the frequency of injection during opiate substitution treatment. For example, such individuals might be under-sampled in studies of injectors recruited in the community at needle exchanges or other venues for active injectors,50 and they might be at decreased risk of HIV infection.11 45 51 If this is the case, our synthesis would underestimate the reduction in risk of HIV infection associated with opiate substitution treatment. Equally, individuals that enter treatment might be more motivated and more likely to change behaviour, thereby reducing injecting frequency or the sharing of equipment, or both, which might overestimate the effect of opiate substitution treatment on risk of HIV infection.

Our finding regarding methadone detoxification treatment might also reflect selection bias if individuals who enter detoxification are less likely to permanently reduce injecting drug use compared with those entering opiate substitution treatment. In some countries, detoxification treatment might be compulsory or be a requirement before entry to opiate substitution treatment (as in Thailand, where opiate substitution treatment is provided only after several unsuccessful attempts at 45 day methadone detoxification).17 Outcomes of treatment might therefore differ among those who self initiate treatment with higher motivation to change compared with those for whom treatment is compulsory. Additionally, high rates of relapse have been reported after detoxification,52 53 54 which might put these individuals at greater risk of HIV infection. Therefore, if individuals with less motivation to reduce injecting drug use and higher relapse rates were more likely to receive methadone detoxification, the potential impact of detoxification treatment could be underestimated.

We could not compare the association between type of opiate substitution treatment and HIV transmission as studies on non-methadone treatment, such as buprenorphine maintenance treatment, did not meet eligibility criteria (see table F in appendix 1). Although this limits generalisability of our findings, systematic reviews report that several other treatment outcomes—such as retention—are found to be similar for buprenorphine and methadone.55 Most studies also used self reported binary measures of methadone maintenance treatment, which precluded us from exploring the relation between methadone dose and risk of HIV infection. Evidence suggests that doses of at least 60 mg are required with an extended duration of treatment,45 48 50 and lower doses could be associated with intermittent injecting during treatment. Despite this possibility, we found strong evidence of an association between opiate substitution treatment and reduced risk of HIV seroconversion, suggesting that the observed associations might be conservative estimates of the true association between active engagement with opiate substitution treatment and HIV transmission.

The control of confounders was limited and inconsistent between studies, and in those studies that did incorporate confounders (unpublished data from A Judd and J Bruneau, 2012)17 37 39 the intervention effect of opiate substitution treatment was diluted, although still consistent with a strong protective effect. Although we identified heterogeneity between studies, in meta-regression analyses, we found no evidence that this was explained by geographical region, site of recruitment, or the provision of incentives, although there was weak evidence to suggest that there could be greater benefit associated with longer recorded duration of treatment. Published studies provided insufficient data for exploration of further differences in study design and reasons for heterogeneity.

We also cannot discount the possibility that part of the impact of opiate substitution treatment is attributable to the provision of additional interventions such as attendance at needle and syringe exchange programmes, psychosocial interventions, practical support, or supervised injection facilities, which might additionally reduce the risk of injecting if they are combined with opiate substitution treatment.19 56 Individual characteristics such as motivation, social networks, and the extent of engagement in HIV risk behaviours could also play a role.2 Unfortunately the extent to which additional harm reduction services were accessed by participants receiving methadone maintenance treatment could not be deciphered from the data presented in individual studies; and the use of additional drug treatment or other support services was included in multivariable analyses in only one study, which adjusted for detoxification treatment.17

Finally, our search strategy targeted opiate substitution treatment, and our findings on opioid detoxification therefore need to be treated cautiously as other forms of detoxification were not included. The risks and benefits of detoxification should be examined further in future studies, though our findings are consistent with several studies reporting high rates of HIV infection among people exposed to detoxification treatment and in countries where maintenance treatment is unavailable.23 57 58 59 60 61

Implications

The search strategy we used enabled us to identify several relevant articles not included in previous narrative or systematic reviews. In this way, our study suggests that that more widespread registration of such cohort studies and/or publication of characteristics of cohort studies and the variables measured62 could play a role in strengthening future systematic reviews while also limiting publication bias.

Our findings further support and highlight the importance of opiate substitution treatment in the prevention of HIV among people who inject (opiate) drugs. The incidence of HIV in people who inject drugs continues to rise in many parts of the world5 6 15 and HIV infection in such people has been shown to increase the probability of death almost sixfold (range 3.5-10.1) before long term cessation of injection, in the absence of antiretroviral treatment.63 There is good evidence showing that opiate substitution treatment is associated with reductions in the frequency of injecting, the sharing of injection equipment, and drug related HIV risk scores,19 21 and it is likely that the association between treatment and reduced risk of HIV infection is mediated by these changes in behaviour. Involvement in such treatment, as part of a package of interventions, might also increase engagement with health services and access to care and services focused on HIV prevention. Opiate substitution treatment for people who inject drugs and have HIV improves adherence and the virological response to antiretroviral treatment, which might therefore reduce the likelihood of onward transmission.19 64 65

Despite this, the coverage of opiate substitution treatment is variable worldwide, with recent estimates indicating that only 6-12% of people who inject drugs receive it.23 Critically, provision of this treatment is minimal in many of the countries with highest prevalence of HIV in people who inject drugs,66 67 and treatment for opiate dependence with methadone remains illegal in Russia.58 Increased coverage in many of these countries,15 24 25 however, is a welcome advance.

Most studies included in our review examined the impact of opiate substitution treatment alone in relation to HIV transmission and only one study examined opiate substitution treatment alone and in combination with needle and syringe exchange programmes.45 Emerging evidence indicates that adequate coverage with opiate substitution treatment and needle and syringe exchange programmes reduces the risk of transmission of HIV (and hepatitis C virus) to a greater extent than either intervention alone,45 50 68 and modelling studies suggest additional benefits in reducing HIV incidence if people who inject drugs who have HIV receive antiretroviral therapy (ART) at the same time as opiate substitution treatment and needle and syringe exchange programmes.69 Further studies are needed to assess the impact of “comprehensive,” or combinations of, interventions including opiate substitution treatment, in a range of settings,19 including prison.70 71 Notably, we identified few studies carried out in low or middle income countries, and further evidence of the effectiveness of harm reduction approaches is required in these settings.

Conclusions

HIV/AIDS account for nearly a fifth of the burden of disease among people who use illicit drugs,72 and increases in HIV incidence have recently been reported among people who inject drugs in several different countries across geographical regions. Our study provides strong quantitative evidence of an association between opiate substitution treatment and reduced risk of HIV transmission among people who inject drugs. These data further support studies showing a range of benefits of opiate substitution treatment, and support calls for the global increase of harm reduction interventions to reduce the transmission of HIV between people who inject drugs and between people who inject drugs and the wider community.

What is already known on this topic

Opiate substitution treatment is effective for heroin and other opioid dependence and might reduce HIV transmission among people who inject drugs, primarily by reducing the frequency of unsafe injections

What this study adds

Pooling of published and unpublished observational studies showed that opiate substitution treatment is associated with a substantial reduction in risk of HIV infection among people who inject drugs

Though we did not find evidence of an association between detoxification and risk of HIV infection, the findings might reflect comparatively high levels of motivation to change behaviour among individuals exposed to opiate substitution treatment

Findings could also reflect the additional benefit of other interventions provided alongside such treatment, such as needle and syringe exchange programmes, psychosocial interventions, practical support, or supervised injection facilities

We thank Jonathan Sterne for helpful advice regarding data analyses and Ali Judd for providing unpublished data for our analyses regarding HIV incidence and exposure to opiate substitution treatment among people who inject drugs.

Contributors: MH was responsible for conception of study; MH and GJM were responsible for design of the study; GJM for literature searching and data analyses. SM, NM, PV and MH contributed to the screening and data extraction. SD and JB contributed unpublished data for the study. GJM wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to interpretation of data and critical revision of the article for intellectual content. MH is guarantor.

Funding: GJM is funded by the South West Public Health Training Scheme; PV is funded by an MRC New Investigators Award (G0701627); MH is supported by the Nationally Integrated Quantitative Understanding of Addiction Harm (NIQUAD) MRC addiction research cluster. The work was undertaken with the support of The Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer), a UKCRC Public Health Research: Centre of Excellence. Funding from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council (RES-590-28-0005), Medical Research Council, the Welsh Assembly Government and the Wellcome Trust (WT087640MA), under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged. The funders had no role in the design, execution, and writing up of the study.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: JB has received funding from Merck to attend a scientific meeting unrelated to this study; LD has received two educational grants from Reckitt Benckiser (they had no role in any aspect of study design, conduct, analysis, interpretation, or publication and have no knowledge of this current study). LD has received payment to deliver a presentation at a conference organized by Pfizer; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e5945

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix 1: Supplementary tables A-F

Appendix 2: Supplementary figures A-C

References

- 1.UNAIDS, Health Canada, Open Society Institute, Canadian International Development Agency. The Warsaw declaration: a framework for effective action on HIV/AIDS and injecting drug use. Second international policy dialogue on HIV/AIDS. 2003. [PubMed]

- 2.Strathdee SA, Hallett TB, Bobrova N, Rhodes T, Booth R, Abdool R, et al. HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: the past, present, and future. Lancet 2010;376:268-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruneau J, Daniel M, Abrahamowicz M, Zang G, Lamothe F, Vincelette J. Trends in human immunodeficiency virus incidence and risk behavior among injection drug users in Montreal, Canada: A 16-year longitudinal study. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:1049-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhodes T, Ball A, Stimson GV, Kobyshcha Y, Fitch C, Pokrovsky V, et al. HIV infection associated with drug injecting in the newly independent states, eastern Europe: the social and economic context of epidemics. Addiction 1999;94:1323-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee SA, et al. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet 2008;372:1733-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiessing L, van de Laar MJ, Donoghoe MC, Guarita B, Klempova D, Griffiths P. HIV among injecting drug users in Europe: increasing trends in the East. Euro Surveill 2008;13:19067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiessing L, Likatavicius G, Hedrich D, Guarita B, van den Laar MJ, Vicente J. Trends in HIV and hepatitis c virus infections among injecting drug users in Europe, 2005-2010. Euro Surveill 2011;16:20031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson KE, Galai N, Safaeian M, Strathdee SA, Celentano DD, Vlahov D. Temporal trends in the incidence of human immunodeficiency virus infection and risk behavior among injection drug users in Baltimore, Maryland, 1988-1998. Am Epidemiol 2002;156:641-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Des Jarlais DC, Marmor M, Friedmann P, Titus S, Aviles E, Deren S, et al. HIV incidence among injection drug users in New York City, 1992-1997: evidence for a declining epidemic. Am J Pub Health 2000;90: 352-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.European Centre for Monitoring of Drugs and Drug Addiction, European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Joint EMCDDA and ECDC rapid risk assessment: HIV in injecting drug users in EU/EEA, following a reported increase of cases in Greece and Romania. 2012. EMCDDA and ECDC.

- 11.Vanichseni S, Kitayaporn D, Mastro TD, Mock PA, Raktham S, Des Jarlais DC, et al. Continued high HIV-1 incidence in a vaccine trial preparatory cohort of injection drug users in Bangkok, Thailand. AIDS 2001;15:397-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhodes T, Lowndes C, Judd A, Mikhailova LA, Sarang A, Rylkov A, et al. Explosive spread and high prevalence of HIV infection among injecting drug users in Togliatti City, Russia. AIDS 2002;16:F25-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skidmore CA, Robertson JR, Savage G. Mortality and increasing drug use in Edinburgh: implications for HIV epidemic. Scott Med J 1990;35:100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uuskula A, McNutt L, Dehovitz J, Fischer K, Heimer R. High prevalence of blood-borne virus infections and high-risk behaviour among injecting drug users in Tallinn, Estonia. Int J STD AIDS 2007;18:41-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma M, Oppenheimer E, Saidel T, Loo V, Garg R. A situation update on HIV epidemics among people who inject drugs and national responses in South-East Asia Region. AIDS 2009;23:1405-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrell M, Wodak A, Gowing L. Maintenance drugs to treat opioid dependence. BMJ 2012;344:e2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suntharasamai P, Martin M, Vanichseni S, Van GF, Mock PA, Pitisuttithum P, et al. Factors associated with incarceration and incident human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among injection drug users participating in an HIV vaccine trial in Bangkok, Thailand, 1999-2003. Addiction 2009;104:235-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malta M, Strathdee SA, Magnanini MMF, Bastos FI. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome among drug users: A systematic review. Addiction 2008;103:1242-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tilson H, Aramrattana A, Bozzette SA, Celentano DD, Falco M, Hammett TM, et al. Preventing HIV infection among injecting drug users in high-risk countries: an assessment of the evidence. Institute of Medicine, 2007.

- 20.Cornish R, Macleod J, Strang J, Vickerman P, Hickman M. Risk of death before and after opiate substitution treatment in primary care: prospective observational study in UK general practice research database. BMJ 2010;341:c5475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gowing L, Farrell MF, Bornemann R, Sullivan LE, Ali R. Oral substitution treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;8:CD004145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Mathers B, Briegleb C, Hammad A, Hickman M. Mortality among regular or dependent users of heroin and other opioids: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction 2010;106:32-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Ali H, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Mattick RP, et al. HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global, regional, and national coverage. Lancet 2010;375:1014-028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaub M, Subata E, Chtenguelov V, Weiler G, Uchtenhagen A. Feasibility of buprenorphine maintenance therapy programs in the Ukraine: first promising treatment outcomes. Eur Addict Res 2009;15:157-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yin W, Hao Y, Sun X, Gong X, Li F, Li J, et al. Scaling up the national methadone maintenance treatment program in China: achievements and challenges. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:ii37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar MS, Agrawal A. Scale up of opioid substitution therapy in India: opportunities and challenges. Int J Drug Pol 2012;23:169-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorensen JL, Copeland AL. Drug abuse treatment as an HIV prevention strategy: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2000;59:17-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley, 2011. www.cochrane-handbook.org/.

- 29.Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group. Suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2009.

- 30.Sterne JAC, Harbord RM. Funnel plots in meta-analysis. STATA J 2004;4:127-41. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger M, Davey-Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA 1998;280:1690-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harbord RM, Higgins JPT. Meta-regression in STATA. STATA J 2008;8:493-519. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhoades HM, Creson D, Elk R, Schmitz J, Grabowski J. Retention, HIV risk, and illicit drug use during treatment: Methadone dose and visit frequency. Am J Public Health 1998;88:34-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters AD, Reid MM. Methadone treatment in the Scottish context: outcomes of a community-based service for drug users in Lothian. Drug Alcohol Depend 1998;50:47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McFarland W, Kellogg TA, Louie B, Murrill C, Katz MH. Low estimates of HIV seroconversions among clients of a drug treatment clinic in San Francisco, 1995 to 1998. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2000;23:426-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerr T, Stoltz J-A, Strathdee S, Li K, Hogg RS, Montaner JS, et al. The impact of sex partners’ HIV status on HIV seroconversion in a prospective cohort of injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;41:119-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruan Y, Qin G, Yin L, Chen K, Qian H-Z, Hao C, et al. Incidence of HIV, hepatitis C and hepatitis B viruses among injection drug users in southwestern China: a 3-year follow-up study. AIDS 2007;21(suppl 8): S39-46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Chitwood DD, Griffin DK, Comerford M, Page JB, Trapido EJ, Lai S, et al. Risk factors for HIV-1 seroconversion among injection drug users: a case-control study. Am J Public Health 1995;85:1538-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bruandet A, Lucidarme D, Decoster A, Ilef D, Harbonnier J, Jacob C, et al. Incidence and risk factors of hcv infection in a cohort of intravenous drug users in the north and east of france. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 2006;54:1S15-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smyth BP, O’Connor JJ, Barry J, Keenan E. Retrospective cohort study examining incidence of HIV and hepatitis C infection among injecting drug users in Dublin. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:310-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Beek I, Dwyer R, Dore GJ, Luo K, Kaldor JM. Infection with HIV and hepatitis C virus among injecting drug users in a prevention setting: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 1998;317:433-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moss AR, Vranizan K, Gorter R, Bacchetti P, Watters J, Osmond D. HIV seroconversion in intravenous drug users in San Francisco, 1985-1990. AIDS 1994;8:223-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Metzger DS, Woody GE, McLellan AT, O’Brien CP, Druley P, Navaline H, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among intravenous drug users in- and out-of-treatment: an 18-month prospective follow-up. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1993;6:1049-56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van den Berg C, Smit C, Van BG, Coutinho R, Prins M, Amsterdam C. Full participation in harm reduction programmes is associated with decreased risk for human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus: evidence from the Amsterdam Cohort Studies among drug users. Addiction 2007;102:1454-462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams AB, McNelly EA, Williams AE, D’Aquila RT. Methadone maintenance treatment and HIV type 1 seroconversion among injecting drug users. AIDS Care 1992;4:35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zangerle R, Fuchs D, Rossler H, Reibnegger G, Riemer Y, Weiss SH, et al. Trends in HIV infection among intravenous drug users in Innsbruck, Austria. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1992;5:865-71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Serpelloni G, Carrieri MP, Rezza G, Morganti S, Gomma M, Binkin N. Methadone treatment as a determinant of HIV risk reduction among injecting drug users: a nested case-control study. AIDS Care 1994;6:215-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Judd A, Hickman M, Jones S, McDonald T, Parry JV, Stimson GV, et al. Incidence of hepatitis C virus and HIV among new injecting drug users in London: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2005;330:24-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turner K, Hutchinson S, Vickerman P, Hope V, Craine N, Palmateer N, et al. The impact of needle and syringe provision and opiate substitution therapy on the incidence of Hepatitis C virus in injecting drug users: pooling of UK evidence. Addiction 2011;106:1978-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deren S, Kang SY, Colon HM, Andia JF, Robles RR. HIV incidence among high-risk Puerto Rican drug users: a comparison of East Harlem, New York, and Bayamon, Puerto Rico. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004;36:1067-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gandhi DH, Jaffe JH, McNary S, Kavanagh GJ, Hayes M, Currens M. Short-term outcomes after brief ambulatory opioid detoxification with buprenorphine in young heroin users. Addiction 2002;98:453-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teesson M, Ross J, Darke S, Lynskey M, Ali R, Ritter A, et al. One year outcomes for heroin dependence: findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS). Drug Alcohol Depend 2006;83:174-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu H, Grusky O, Zhu Y, Li X. Do drug users in China who frequently receive detoxification treatment change their risky drug use practices and sexual behavior? Drug Alcohol Depend 2006;84:114-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;3:CD002207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palmateer N, Kimber J, Hickman M, Hutchinson S, Rhodes T, Goldberg D. Evidence for the effectiveness of sterile injecting equipment provision in preventing hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus transmission among injecting drug users: a review of reviews. Addiction 2010;105:844-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kitayaporn D, Uneklabh C, Weniger BG, Lohsomboon P, Kaewkungwal J, Morgan WM, et al. HIV-1 incidence determined retrospectively among drug users in Bangkok, Thailand. AIDS 1994;8:1443-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rhodes T, Sarang A, Vickerman P, Hickman M. Why Russia must legalise methadone. BMJ 2010;341:129-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Celentano DD, Hodge MJ, Razak MH, Beyrer C, Kawichai S, Cegielski JP, et al. HIV-1 incidence among opiate users in northern Thailand. Am J Epidemiol 1999;149:15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rhodes T, Platt L, Maximova S, Koshkina E, Latishevskaya N, Hickman M, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis C and syphilis among injecting drug users in Russia: a multi-city study. Addiction 2006;101:252-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stachowiak JA, Tishkova FK, Strathdee SA, Stibich MA, Latypov A, Mogilnii V, et al. Marked ethnic differences in HIV prevalence and risk behaviors among injection drug users in Dushanbe, Tajikistan. Drug Alcohol Depend 2004;82(suppl 1):S7-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marmot M, Brunner E. Cohort profile: the Whitehall II study. Int J Epidemiol 2004;34:251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kimber J, Copeland L, Hickman M, Macleod J, McKenzie J, De AD, et al. Survival and cessation in injecting drug users: prospective observational study of outcomes and effect of opiate substitution treatment. BMJ 2010;341:c3172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roux P, Carrieri MP, Villes V, Dellamonica P, Poizot-Martin I, Ravaux I, et al. The impact of methadone or buprenorphine treatment and ongoing injection on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) adherence: Evidence from the MANIF2000 cohort study. Addiction 2008;103:1828-36.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Joy R, Kerr T, Wood E, Press N, et al. Antiretroviral adherence and HIV treatment outcomes among HIV/HCV co-infected injection drug users: the role of methadone maintenance therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006;84:188-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sharma M, Burrows D, Bluthenthal R. Coverage of HIV prevention programmes for injection drug users: confusions, aspirations, definitions and ways forward. Int J Drug Pol 2007;18:92-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wiessing L, Likatavicius G, Klempová D, Hedrich D, Nardone A, et al. Associations between availability and coverage of HIV-prevention measures and subsequent incidence of diagnosed HIV infection among injection drug users. Am J Public Health 2009;99:1049-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vickerman P, Martin N, Turner K, Hickman M. Can needle and syringe programmes and opiate substitution therapy achieve substantial reductions in HCV prevalence? Model projections for different epidemic settings. Addiction 2012;May 7;10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Degenhardt L, Mathers B, Vickerman P, Rhodes T, Latkin C, Hickman M. Prevention of HIV infection for people who inject drugs: Why individual, structural, and combination approaches are needed. Lancet 2010;376:285-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Larney S. Does opioid substitution treatment in prisons reduce injecting-related HIV risk behaviours? A systematic review. Addiction 2010;105:216-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hedrich D, Alves P, Farrell M, Stover H, Moller L, Mayet S. The effectiveness of opioid maintenance treatment in prison settings: a systematic review. Addiction 2011;107:501-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Degenhardt L, Hall W. Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet 2012;379:55-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Supplementary tables A-F

Appendix 2: Supplementary figures A-C