Abstract

The objective of this study was to examine the associations between attendance at childbirth education classes and maternal characteristics (age, income, educational level, single parent status), maternal psychological states (fear of birth, anxiety), rates of obstetric interventions, and breastfeeding initiation. Between women’s 35th and 39th weeks of gestation, we collected survey data about their childbirth fear, anxiety, attendance at childbirth education classes, choice of health-care provider, and expectations for interventions; we then linked women’s responses (n = 624) to their intrapartum records obtained through Perinatal Services British Columbia. Older, more educated, and nulliparous women were more likely to attend childbirth education classes than younger, less educated, and multiparous women. Attending prenatal education classes was associated with higher rates of vaginal births among women in the study sample. Rates of labor induction and augmentation and use of epidural anesthesia were not significantly associated with attendance at childbirth education classes. Future studies might explore the effect of specialized education programs on rates of interventions during labor and mode of birth.

Keywords: childbirth education, prenatal classes, obstetric interventions, low-risk pregnant women

Historically, the purpose of prenatal education classes was to prepare childbearing women for birth and to teach them pain management techniques during labor. The scope of prenatal education has expanded over the years and now includes preparation for pregnancy, labor and birth, care of the newborn, and adjustment to family life with a baby (Chalmers & Kingston, 2009; Nichols & Humenick, 2000).

Prenatal education classes in British Columbia, Canada, are offered by health-care professionals and childbirth educators. Classes differ in length, content, and affiliations. Some are associated with particular hospitals, and others are offered through community-based organizations. For example, BC Women’s Hospital in British Columbia has the largest volume of births in the province and offers two types of prenatal classes: a 1-day intensive (7 hr) course or a 6-week course (16 hr of instruction). Both formats include education about psychological and physical changes associated with late pregnancy, how to know when labor has started, events in labor and birth and their variations, characteristics of the newborn in the first hours, breastfeeding promotion, a tour of the maternity ward, and an optional 2-hr breastfeeding class (BC Women’s Hospital, 2011).

Some community-based childbirth education providers explicitly state their childbirth philosophies. For example, Douglas College in New Westminster, British Columbia, offers a curriculum centered on Lamaze International’s (2012) approach to birth and provides childbirth education classes in the Greater Vancouver Regional District. Their 6-week program and 1-day intensive course both include components on communication with maternity care providers and informed decision making during pregnancy and birth (Douglas College, 2011).

Benefits of prenatal education classes have included increased confidence for labor and birth among women who attended prenatal classes, higher likelihood of breastfeeding, improved communication between childbearing women and their maternity care providers, decreased need for analgesic medication in labor, and increased satisfaction with birth (Chalmers & Kingston, 2009; Enkin et al., 2000).

Notwithstanding, a literature review of the effectiveness of childbirth education revealed inconclusive findings and the propensity of authors to view childbirth education as a single intervention without taking into consideration confounding factors. In addition, existing studies measured numerous different outcomes, which makes it difficult to compare these studies and draw valid conclusions about the benefits of childbirth education (Koehn, 2002). When comparing specific models of childbirth education (CenteringPregnancy) to standard prenatal care using random assignment of women, CenteringPregnancy is associated with better outcomes. In a randomized controlled trial of 1,047 pregnant women aged 14–25 years old, women who attended the 10-week CenteringPregnancy program had a 33% reduction in preterm births and higher rates of breastfeeding initiation, reported a higher level of readiness for labor and birth, and felt more satisfied with their care (Ickovics et al., 2007).

In a large representative survey of childbearing women in Canada (n = 6,421), about one third (32.7%, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 31.7–33.7) of women reported attending childbirth education classes (Chalmers & Kingston, 2009). Nulliparas attended classes more frequently (65.6%) than multiparas (6.0%). Women between the ages of 15 and 19 years old were more likely to attend classes compared to all other age groups. Women with low incomes were significantly less likely to attend classes, compared with women with a family income above the low-income cutoff. Of the women who attended childbirth education classes, 35% attended classes at a hospital, 25% at a health clinic, 21% at a community center, 12% in private settings, and 6% at unspecified locations (Chalmers & Kingston, 2009).

In a representative survey (n = 1,573) of American women aged 18–45 years old who gave birth to a singleton in a hospital in 2005, 25% of respondents (56% of nulliparas and 9% of multiparas) reported taking childbirth education classes (Declercq, Sakala, Corry, & Applebaum, 2006). Locations of classes varied, but 87% of women attended classes in a clinical setting (hospitals and clinics). When the American women in this survey were asked why they attended childbirth education classes, 82% reported that they wanted to learn about labor and birth, and 37% specifically indicated they were interested in achieving a natural labor and birth. In relation to the impact of their childbirth education classes, 88% of the women indicated they had become more aware of maternity care options after taking classes, 78% felt more confident in their ability to give birth, and 70% described better communication with their maternity care providers. The women in the survey reported greater trust in their hospitals (60%) and care providers (54%) and less fear about medical interventions (58%) after attending childbirth education classes. Some women reported negative effects of childbirth education classes, such as increased fear of birth (14%; Declercq et al., 2006). Although these findings support the positive impact of childbirth education classes, for some women, they raise questions about whether clinically based classes increase women’s comfort with routine hospital procedures, prepare them for medical interventions, and increase their fear about birth.

CHILDBIRTH EDUCATION AND OBSTETRIC OUTCOMES

In an Australian study, researchers interviewed 398 low-risk primiparous women about their experiences with childbirth education 3 weeks after birth and linked women’s responses to their hospital records (Bennett, Hewson, Booker, & Holliday, 1985). Most women (81%) attended childbirth education classes. The researchers created four categories to measure exposure to childbirth education: none (0 hours); low attendance (1–12 hr); medium attendance (13–19 hr); and high attendance (>20 hr). Their findings indicated that women with more hours of childbirth education (>13 hr) were older, reported higher socioeconomic status, and were more likely to have partners who attended classes compared to women with fewer hours of preparation.

The number of hours that the Australian women attended childbirth education classes was not related to rates of labor augmentation, length of labor, or mode of birth, but women who spent more hours in classes were less likely to use medication during labor and more likely to breastfeed their infants (Bennett et al., 1985). Women with more hours of childbirth education reported similar pain ratings to those of women who attended fewer hours, but women attending more hours were significantly less likely to receive epidural anesthesia and more likely to use nonpharmacological methods of pain relief.

In another study, Sturrock and Johnson (1990) reviewed records of 207 nulliparas in the United States to examine the association between attendance at childbirth education classes and labor and birth outcomes. Women who attended two to four classes were classified as attenders (55%), and women who attended zero to one class were labeled as nonattenders (45%). Attenders were significantly older and more educated than nonattenders. Although attenders had longer second stages of labor, experienced more instrumental vaginal births, and were more likely to use pain medication during labor, those associations were not significant. The authors concluded that childbirth education classes conferred no benefits in terms of reducing interventions during labor and birth.

Lumley and Brown (1993) dichotomized attendance at childbirth education classes (yes or no). The researchers sent a survey to 1,193 Australian women who had recently given birth. They reported findings for the 292 primiparous women who participated in the survey. Of those women, 83.9% attended childbirth education classes. Attenders were significantly older and more educated and reported higher incomes than nonattenders. The differences between the two groups of women on measures of pain and use of obstetric procedures, interventions, and pain relief were very small and not significant, with the exception of induction of labor. Women who did not attend classes were significantly more likely to have an induction compared to attenders (51.2% vs. 30.1%, p = 0.008). Women who attended childbirth education classes were significantly more likely to breastfeed right after birth and at 3 months postpartum, to miss fewer prenatal appointments, and to consume any alcohol during their pregnancies, but they were less likely to smoke.

The three studies summarized have in common the finding that older and more educated and affluent nulliparas are more likely to attend childbirth education classes. The association between childbirth education and labor and birth outcomes was inconclusive in that one study found no association, another detected decreased use of pain medications among attenders, and the third study found that nonattenders were significantly more likely to be induced. The three studies were published between 20 and 25 years ago. Since then, rates of cesarean surgery, induction of labor, and use of epidural anesthesia have increased in Canada (Canadian Institute of Health Information, 2010; Low, 2009), along with interest in exploring factors associated with these increases.

STUDY OBJECTIVES

The objectives of this study were to examine the associations between attendance at childbirth education classes and the following factors: (a) maternal characteristics (age, income, educational level, single parent status); (b) maternal psychological states (fear of birth, anxiety) and type of maternity care received; and (c) prenatal expectations for obstetric interventions, actual rates of obstetric interventions (induction and augmentation of labor, use of epidural anesthesia, instrumental vaginal birth, and cesarean surgery), and breastfeeding initiation in a sample of 624 childbearing women from British Columbia, Canada, at low risk for complications.

METHODS

This study was a secondary analysis of survey data that were collected prenatally and then linked to participants’ obstetric records. The primary aim of the survey was to assess relationships between fear of birth, anxiety, fatigue, sleep deprivation, and maternal characteristics in pregnant women. Results from that analysis are published elsewhere (Hall et al., 2009).

A sample size calculation determined that at least 150 respondents were needed for power in excess of .85, assuming medium effect sizes and alpha = .05, for all analyses (see Hall et al., 2009). The convenience sample included pregnant women who were between 35 and 39 weeks of gestation, resided in British Columbia at the time of data collection, could speak and read English, and had no medical complications during pregnancy (e.g., bleeding, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and gestational diabetes).

Women were recruited via study advertisements from various clinical settings (care providers’ offices) and nonclinical settings (community centers, laboratories, baby fairs) to participate in a paper-based survey about psychological states during pregnancy. Women who were interested in participating in this study were invited to contact the study coordinator who sent out the survey along with a self-addressed stamped envelope to eligible women. Data were collected between May 2005 and July 2007.

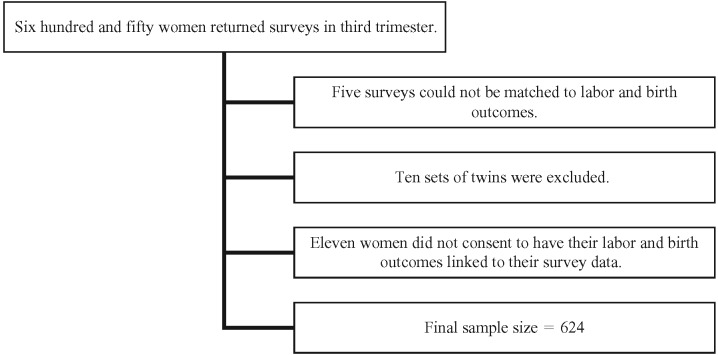

Following the collection and analysis of survey data, maternal and newborn data were obtained from Perinatal Services British Columbia using the personal health numbers of women who consented to have their maternal and newborn records linked to their survey data. Perinatal Services British Columbia collects clinical data for the province of British Columbia, which are abstracted from maternal and newborn records. Twins (n = 10 sets) were excluded from our analysis and five cases could not be matched, reducing the sample size to 635 women. Eleven of the 635 women were excluded from the analysis because they did not consent to have their records linked to the survey data (final n = 624; see Figure 1). This study was reviewed and approved by the University of British Columbia Behavioural Ethics Review Board and BC Women’s and Children’s Hospital Ethics Committee.

FIGURE 1.

Cases excluded from analysis.

Measures

In the prenatal questionnaire, demographic information was obtained on numerous variables, including the following: maternal age, relationship status, self-identified ethnicity, number of previous pregnancies, education level, family income, type of primary maternity care provider, intention to request cesarean surgery, expectations for other obstetric interventions, and attendance at childbirth education classes. Women were not asked about the type or number of childbirth education classes they had attended; they were asked whether they did or did not attend any classes.

Respondents were also asked to complete several standardized measurement tools including the Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire-A (W-DEQ) and the Spielberger’s State Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S). The 33-item W-DEQ is used to measure women’s fear of childbirth. Scores on the W-DEQ range from 0 to 165, with scores over 66 indicating high fear of childbirth (Wijma, Wijma, & Zar, 1998). The STAI-S is a widely used, 20-item measure of subjective current feelings of anxiety. Scores on the STAI-S range from 20 to 80, with scores above the median (40) indicating heightened anxiety (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983). Both tools had excellent interitem correlations when applied to the study sample (Cronbach’s alpha = .92 for W-DEQ and .93 for the STAI-S).

From Perinatal Services British Columbia, we obtained data on women’s parity, labor and delivery outcomes, including epidural anesthesia, any type of anesthesia, instrumental birth (forceps or vacuum extraction), mode of birth (cesarean surgery or vaginal birth), type of cesarean surgery (emergent, scheduled), infant macrosomia, and rates of exclusive breastfeeding.

Data Analysis

Associations between childbirth education and maternal characteristics and labor and birth outcomes were measured using the chi-square test (df = 1). Because this was an exploratory study, p values of less than .05 were deemed statistically significant. Using logistic regression modeling, attendance at childbirth education classes was examined as an independent predictor of cesarean surgery among nulliparas, controlling for maternal age, education, prenatal requests for cesarean surgery, and infant macrosomia. Attendance at childbirth education classes (yes or no) was entered in the first step of the model, followed by the control variables in Step 2. PASW Statistics version 18 (IBM) was used to perform all analyses.

RESULTS

Of the 624 women who were included in the analysis, 55% attended childbirth education classes. Of those women, 83.6% were nulliparas and 12.7% were multiparas. One in five nulliparas and one in three multiparas were older than the age of 35 years, and most of the entire study sample was partnered (see Table 1). Overall, the sample were well educated, and most reported to have family incomes above the low-income cutoff for British Columbia. Uptake of midwifery services was higher among multiparas than nulliparas.

TABLE 1. Maternal Characteristics Stratified by Parity and Attendance at Childbirth Education Classes (n = 624).

| Nulliparas | χ2 | p | Multiparas | χ2 | p | |||

| No Classes | Classes | No Classes | Classes | |||||

| (n = 61) | (n = 311) | (n = 220) | (n = 32) | |||||

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |||||

| Age > 35 years old | 13.1 (8) | 14.5 (45) | 0.077 | .782 | 28.2 (62) | 50.0 (16) | 6.223 | .013 |

| Family income < BC average income | 34.4 (21) | 23.5 (73) | 3.240 | .072 | 35.9 (79) | 37.5 (12) | 0.031 | .861 |

| Education | ||||||||

| No university | 63.9 (39) | 40.8 (127) | 11.011 | .001 | 49.5 (109) | 50.0 (16) | 0.002 | .962 |

| University degree | 36.1 (22) | 59.2 (184) | 50.5 (111) | 50.0 (16) | ||||

| Lone parent | 1.6 (1) | 1.9 (6) | 0.023 | .879 | 0.9 (2) | 6.3 (2) | 5.101 | .024 |

Note. Numbers highlighted in bold represent significant findings. BC = British Columbia.

Factors Associated With Childbirth Education Among Nulliparas and Multiparas

Multiparous women who were older than age 35 years and lone parents were significantly more likely to attend childbirth education classes compared to younger multiparous women and those with a partner (see Table 1 for chi-square and p values). Nulliparas who attended classes were significantly more likely to be university educated (59.2%) than those who did not attend classes (36.1%). About a quarter of women reported moderate-to-high fear of birth. Self-reported anxiety was higher among multiparous women than nulliparas, but anxiety and childbirth fear scores did not differ among attenders and nonattenders (see Table 2 for chi-square and p values). No significant differences in attendance were noted among women who received maternity care from midwives, family physicians, or obstetricians.

TABLE 2. Prenatal Fear and Anxiety and Type of Maternity Care Stratified by Parity and Attendance at Childbirth Education Classes (n = 624).

| Nulliparas | χ2 | p | Multiparas | χ2 | p | |||

| No Classes | Classes | No Classes | Classes | |||||

| (n = 61) | (n = 311) | (n = 220) | (n = 32) | |||||

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |||||

| High fear of birth | 23.0 (14) | 25.5 (79) | 0.174 | .676 | 25.9 (57) | 25.0 (8) | 0.012 | .913 |

| High anxiety | 24.6 (15) | 25.1 (78) | 0.007 | .936 | 34.5 (76) | 37.5 (12) | 0.107 | .743 |

| Maternity care provider: midwife | 19.7 (12) | 24.4 (76) | 0.641 | .423 | 25.5 (56) | 34.4 (11) | 1.139 | .286 |

| Maternity care provider: family doctor | 39.3 (24) | 42.4 (132) | 0.201 | .654 | 37.3 (82) | 28.1 (9) | 1.013 | .314 |

| Maternity care provider: obstetrician | 41.0 (25) | 33.1 (103) | 1.398 | .237 | 37.3 (82) | 37.5 (12) | 0.001 | .980 |

Nulliparas were significantly less likely to intend to request cesarean surgery prenatally if they attended childbirth education classes. Rates of labor induction and augmentation were not significantly different for women who attended childbirth education classes, compared to women who did not attend classes. Use of epidural anesthesia or any anesthetic was higher among nulliparas who did not attend classes, but this association was not significant. Use of pain medications during labor was not significantly associated with attendance at childbirth education classes for multiparas either. Attendance at classes was not associated with women’s expectations for other obstetric interventions but was associated with significantly fewer cesarean surgeries (all types) and planned cesarean surgery among first-time mothers. Multiparas who attended childbirth education classes were more than twice as likely to attempt a vaginal birth after cesarean compared to multiparous women who did not attend classes (see Table 3). Although breastfeeding initiation rates were higher among attenders, the differences between groups were not significant.

TABLE 3. Labor and Birth Outcomes, Stratified by Parity and Attendance at Childbirth Education Classes (N = 624).

| Nulliparas | χ2 | p | Multiparas | χ2 | p | |||

| No Classes | Classes | No Classes | Classes | |||||

| (n = 61) | (n = 311) | (n = 220) | (n = 32) | |||||

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |||||

| Inductiona | 36.4 (20) | 23.5 (73) | 3.757 | .053 | 11.6 (21) | 10.3 (3) | 0.039 | .843 |

| Augmentationa | 41.8 (23) | 45.2 (138) | 0.221 | .638 | 34.8 (63) | 41.4 (12) | 0.470 | .493 |

| Epidurala | 56.4 (31) | 43.9 (134) | 2.900 | .089 | 14.9 (27) | 20.7 (6) | .0629 | .428 |

| Any anesthetica | 98.2 (54) | 91.1 (278) | 3.214 | .073 | 73.5 (133) | 72.4 (21) | 0.015 | .904 |

| Cesarean surgery (all types) | 49.2 (30) | 30.2 (94) | 8.246 | .004 | 25.9 (57) | 25.0 (8) | 0.012 | .913 |

| Emergency cesarean surgery | 39.4 (24) | 28.3 (88) | 2.958 | .085 | 8.2 (18) | 15.6 (5) | 1.866 | .172 |

| Planned cesarean surgery | 9.8 (6) | 1.9 (6) | 10.213 | .001 | 17.7 (39) | 9.4 (3) | 1.403 | .236 |

| Intention to request cesarean surgeryb | 6.6 (4) | 0.6 (2) | 11.241 | .001 | 1.9 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.447 | .504 |

| Expecting obstetric interventionsb | 10.0 (6) | 16.1 (50) | 1.470 | .225 | 12.2 (19) | 13.0 (3) | 0.014 | .906 |

| Instrumental vaginal birthc | 25.8 (8) | 22.8 (49) | 0.138 | .710 | 5.6 (9) | 12.5 (3) | 1.644 | .200 |

| Vaginal birth after cesarean attempted (eligible women only) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 31.7 (20) | 66.7 (6) | 4.162 | .041 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding at birth | 73.8 (45) | 81.4 (253) | 1.839 | .175 | 76.4 (168) | 87.5 (28) | 2.005 | .157 |

Note. Numbers highlighted in bold represent significant findings.

aWomen with planned cesarean surgery excluded.

bWomen with previous cesarean surgery excluded.

cAs a proportion of all vaginal births.

Prenatal Education and Mode of Birth Among Nulliparas

The cesarean surgery rate for nulliparas who did not attend childbirth education classes was nearly 50% or more than twice the national average primary cesarean surgery rate in Canada (Canadian Institute of Health Information, 2010). Because a group of low-risk women had been surveyed, the high rate warranted further investigation. Using logistic regression analysis, attendance at classes was associated with decreased odds of having a cesarean surgery (odds ratio [OR] = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.26–0.83; p = .009) after controlling for maternal age older than 35 years, educational level, prenatal intention to request cesarean surgery, and infant macrosomia.

DISCUSSION

Women in the study sample were on average 1.3 years older when compared to the overall childbearing population in British Columbia between 2005 and 2007, and women who used midwifery services were overrepresented in the study sample (British Columbia Perinatal Health Program, 2010). This study supports earlier findings that nulliparas, older parturient women (older than 35 years), and women who are more educated are more likely to attend childbirth education classes (Bennett et al., 1985; Lumley & Brown, 1993; Nichols, 1995; Sturrock & Johnson, 1990). However, the findings stand in contrast to those of a national survey of Canadian women that found highest participation rates among young women aged 15–19 years old (Chalmers & Kingston, 2009).

When stratifying women by parity, attendance at childbirth education classes was associated with a significantly lower cesarean surgery rate. Nonattendance at childbirth education classes was a significant independent predictor of having cesarean surgery among nulliparas, after controlling for prenatal intent to have cesarean surgery, infant macrosomia, maternal age, and education. The significant difference in the cesarean surgery rate among attenders and nonattenders was nearly 20% among nulliparous women. Among multiparous women, more than twice as many women attempted a vaginal birth after cesarean if they attended childbirth education classes. These findings demonstrate a positive relationship between childbirth education and frequency of vaginal birth and are supported by an earlier study by Hetherington (1990) who reported that rates of spontaneous vaginal birth were significantly higher among women who attended childbirth education classes (79% vs. 51%).

The absence of differences in fear of childbirth and anxiety scores between attenders and nonattenders suggests that these prenatal psychological states are unrelated to women’s attendance at prenatal education classes. A limitation of this study is the lack of assessment of whether participation in childbirth education classes per se increased or decreased fear of birth and anxiety.

In this study, exclusive breastfeeding rates did not differ significantly among attenders and nonattenders. Handfield and Bell (1995) also reported in their study that decisions about breastfeeding are minimally affected by childbirth education classes.

The lack of significant associations in this study between childbirth education classes and interventions such as induction, labor augmentation, and epidural use suggest that these interventions are not influenced by current content received by women in childbirth education classes in British Columbia. Longer exposure to childbirth education was associated with decreased use of epidural anesthesia and increased use of nonpharmacological pain relief in a study by Bennett et al. (1985). Other authors have found no evidence of a positive association between attendance at childbirth education and increased knowledge of common obstetric interventions (Lothian, 2007). Lothian (2007) used data from the Listening to Mothers II survey to examine whether women’s awareness of complications associated with induction of labor and cesarean surgery was increased among women who attended childbirth education classes. Despite 97% of participants reporting that they wanted to be informed about the potential risks of induction and cesarean surgery, most women, regardless of attendance at childbirth education classes, did not identify complications associated with these particular interventions.

Women in this study who attended childbirth education classes were less likely to have cesarean surgery. It is possible that the childbirth education classes attracted more women who were interested in vaginal birth than those interested in cesarean surgery, or it may be that class content about risks associated with cesarean surgery discouraged women from having cesarean surgery. Women had been asked prenatally in the survey study whether they intended to request cesarean surgery; this intention was controlled for when examining the impact of childbirth education on mode of birth among nulliparas.

In addition to childbirth education classes, another important source of information about pregnancy and birth and a potential influence on care choices is the type of maternity care received. Based on findings from the Maternity Care Experience survey (Kingston & Chalmers, 2009), Canadian women rated their maternity care providers as the most important source of pregnancy-related information (32.2%), followed by books, previous pregnancies, family and friends, the Internet, prenatal education classes (approximately 7%), and other (unspecified) sources. Compared to nulliparous women, multiparas reported their health-care providers as more useful and childbirth education classes as less useful. Interprofessional variations in attitudes toward birth among Canadian maternity care providers may be transferred to parturient women, possibly normalizing elective obstetric interventions or discouraging women from seeking them (Klein et al., 2009). The women in our study who attended classes did not differ in terms of their selection of care providers. This finding suggests that women in this study may have been encouraged by all care providers to attend childbirth education classes or may have regarded content from classes as an important supplement to information provided by their care providers.

Implications for Practice

Childbirth education classes in the United States use various methods to “socialize women to comply with hospital routines and expectations” and may fulfill institutional rather than individual needs (Armstrong, 2000, p. 583). Childbirth educators can counteract this trend by facilitating informed choice for childbearing women by providing childbirth curricula that are focused on current evidence, on the physiology and normality of birth, and on medical indications, risks, and benefits associated with obstetric interventions.

There is some empirical evidence that pregnant women who received prenatal education that specifically informed them about risks associated with elective inductions had lower rates of inductions compared to women who did not receive this component of prenatal education (Simpson, Newman, & Chirino, 2010). Although these findings are hopeful, it must be acknowledged that childbirth educators face many obstacles (Lothian, 2007; Morton & Hsu, 2010). Providing pregnant women with information that idealizes the normalcy of birth and questions the use of interventions, particularly in clinical settings, may be difficult given the “reality of giving birth” in a hospital setting.

Implications for Research

It is difficult to assess the benefits of childbirth education because existing research is plagued by inconsistencies in methodology and childbirth education content (Koehn, 2002). In addition, many confounding variables need to be controlled to have confidence that associations between labor and birth outcomes and childbirth education are not spurious. Conducting a randomized controlled trial to compare the effect of different types of prenatal education programs and settings (clinical vs. community based) on labor and birth outcomes, ensuring that baseline maternal characteristics are distributed equally among groups, with adjustment for potential confounders, could advance our understanding about effects of prenatal education.

Limitations

The categorization of women into attenders and nonattenders was a deliberate decision, given the lack of information about the location, content, and length of classes. There are many different philosophies, models, and formats of childbirth education. Relationships among childbirth education and parturient women’s decisions during labor and birth may vary by the philosophy and content of childbirth education classes, the experience or style of educators, the demographics and reproductive history of women, and the maternity care system in which the classes are delivered. This study did not take these factors into account.

The study design did not include information about whether childbirth educators experienced tension between their allegiance to their facilities and childbearing women.

Pregnant women are exposed to a plethora of information about pregnancy and birth from different sources that make it difficult to assess the relative contribution of prenatal education classes (Declercq & Chalmers, 2008). In our study, the effect of all potential sources of prenatal information, such as family and friends, books, and the Internet, was not assessed.

Finally, most prenatal education classes are not designed to reduce rates of obstetric interventions; this limitation must be taken into account when drawing conclusions about any associations between childbirth education and perinatal outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Because childbirth education classes provided in several centers in British Columbia were associated with increased rates of vaginal births among women with low-risk pregnancies, they may serve as an important tool in reducing cesarean surgery rates among low-risk nulliparous women and multiparous women with a previous cesarean. The lack of significant differences in labor interventions between childbirth education class attenders and nonattenders suggests that prenatal educators could consider adding components about the risks and benefits of common elective interventions (e.g., epidural anesthesia for relief of labor pain) to facilitate informed and shared decision making for pregnant women in British Columbia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This project was funded by the Hampton Research Fund Endowment (University of British Columbia).

Biography

KATHRIN H. STOLL recently completed an interdisciplinary doctorate in midwifery, nursing, and epidemiology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

WENDY HALL is a professor in the School of Nursing at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

REFERENCES

- Armstrong E. M. (2000). Lessons in control: Prenatal education in the hospital. Social Problems, 47(4), 583–605 [Google Scholar]

- BC Women’s Hospital (2011). Welcome to the BC women’s prenatal classes online registration. Retrieved from https://edreg.cw.bc.ca/Prenatal/Default.aspx

- Bennett A., Hewson D., Booker E., Holliday S. (1985). Antenatal preparation and labor support in relation to birth outcomes. Birth, 12(l), 9–16 10.1111/j.1523-536X.1985.tb00924.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia Perinatal Health Program (2010). Perinatal health report 2008. Retrieved from http://www.perinatalservicesbc.ca/NR/rdonlyres/3DEC78D6-BDC3-4602-B09B-FB0EE1C7B7D9/0/SurveillanceAnnualReport2008.pdf

- Canadian Institute of Health Information (2010). Highlights of 2008–2009 selected indicators describing the birthing process in Canada. Retrieved from https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productSeries.htm?locale=en&pc=PCC226

- Chalmers B., Kingston D. (2009). Prenatal classes. In What mothers say: The Canadian Maternity Care Experience Survey (pp. 47–50) Ottawa, Canada: Public Health Agency of Canada [Google Scholar]

- Declercq E., Chalmers B. (2008). Mothers’ reports of their maternity experiences in the USA and Canada. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 26(4), 295–308 10.1080/02646830802408407 [Google Scholar]

- Declercq E. R., Sakala C., Corry M. P., Applebaum S. (2006). Listening to mothers II: Report of the second national U.S. survey of women’s childbearing experiences. New York, NY: Childbirth Connection; Retrieved from http://www.childbirthconnection.org/listeningtomothers/ [Google Scholar]

- Douglas College (2011). Prenatal class series. Retrieved from http://www.douglas.bc.ca/programs/continuing-education/programs-courses/perinatal/p_labour.html

- Enkin M., Keirse M., Neilson J., Crowther C., Duley L., Hodnett E., Hofmeyr J. (2000). A guide to effective care in pregnancy and childbirth (3rd ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Hall W. A., Hauck Y. L., Carty E. M., Hutton E. K., Fenwick J., Stoll K. (2009). Childbirth fear, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep deprivation in pregnant women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 38(5), 567–576 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handfield B., Bell R. (1995). Do childbirth classes influence decision making about labor and postpartum issues? Birth, 22(3), 153–160 10.1111/j.1523-536X.1995.tb00692.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington S. E. (1990). A controlled study of the effect of prepared childbirth classes on obstetric outcomes. Birth, 17(2), 86–90 10.1111/j.1523-536X.1990.tb00705.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics J. R., Kershaw T. S., Westdahl C., Magriples U., Massey Z., Reynolds H., Rising S. S. (2007). Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 110(2, Pt. 1), 330–339 10.1097/01.AOG.0000275284.24298.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston D., Chalmers B. (2009). Prenatal information. In What mothers say: The Canadian maternity care experience survey (pp. 51–56). Ottawa, Canada: Public Health Agency of Canada [Google Scholar]

- Klein M., Kaczororwski J., Hall W. A., Fraser W., Liston R. M., Eftekhary S., Chamberlaine A. (2009). The attitudes of Canadian maternity care practitioners towards labour and birth: Many differences but important similarities. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 31(9), 827–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehn M. L. (2002). Childbirth education outcomes: An integrative review of the literature. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 11(3), 10–19 10.1624/105812402X88795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamaze International (2012). The Lamaze approach to birth. Retrieved from http://www.lamazeinternational.org/ApproachToBirth

- Lothian J. A. (2007). Listening to mothers II: Knowledge, decision-making, and attendance at childbirth education classes. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 16(4), 62–67 10.1624/105812407X244723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low J. A. (2009). Operative delivery: Yesterday and today. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 31(2), 132–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumley J., Brown S. (1993). Attenders and nonattenders at childbirth education classes in Australia: How do they and their births differ? Birth, 20(3), 123–130 10.1111/j.1523-536X.1993.tb00435.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton C. H., Hsu C. (2010). Contemporary dilemmas in American childbirth education: Findings from a comparative ethnographic study. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 16(4), 25–37 10.1624/105812407X245614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols F. H., Humenick S. S. (2000). Childbirth education: Practice, research and theory (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders [Google Scholar]

- Nichols M. R. (1995). Adjustment to new parenthood: Attenders versus nonattenders at prenatal education classes. Birth, 22(l), 21–26 10.1111/j.1523-536X.1995.tb00549.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson K. R., Newman G., Chirino O. R. (2010). Patient education to reduce elective labor inductions. American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 35(4), 188–194 10.1097/NMC.0b013e3181d9c6d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C. D., Gorsuch R. L., Lushene R. E., Vagg P. R., Jacobs G. A. (1983). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press [Google Scholar]

- Sturrock W. A., Johnson J. A. (1990). The relationship between childbirth education classes and obstetric outcome. Birth, 17(2), 82–85 10.1111/j.1523-536X.1990.tb00704.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijma K., Wijma B., Zar M. (1998). Psychometric aspects of the W-DEQ: A new questionnaire for the measurement of fear of childbirth. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology, 19, 84–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]