Abstract

Objective

To present a case report detailing the use of an enhanced form of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). The treatment was provided to an adolescent with an eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) diagnosis, and included a focus on the additional maintaining mechanisms of mood intolerance and interpersonal problems.

Case

This case began as an unsuccessful attempt at family therapy, where the underlying dysfunction exacerbated symptoms and demoralized the family. The therapist subsequently chose to utilize an enhanced version of CBT to simultaneously address the patient's symptoms and try to effect change across multiple domains. A description of the patient's eating disorder pathology, the 29-session treatment, and outcome, are provided.

Conclusion

This case study illustrates that it is possible to successfully use enhanced CBT with developmentally appropriate adaptations in the treatment of a young patient with an EDNOS diagnosis, as suggested by Cooper and Stewart (2008).

Keywords: cognitive behavioral therapy, eating disorder not otherwise specified, purging disorder, adolescents

Introduction

The 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; APA; 1994) includes two eating disorders diagnoses: anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN), and a residual category of eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS). Most adults presenting for eating disorder treatment are not classified into the DSM-IV categories of AN or BN (e.g., Fairburn et al., 2007; Ricca et al., 2001; Turner & Bryant-Waugh, 2004), and similarly, most treatment-seeking adolescents are diagnosed with an EDNOS (e.g., Eddy et al., 2008; Nicholls, Chater, & Lask, 2000). For younger populations, the increased prevalence of EDNOS may be related to developmental differences in symptom presentation between adults and adolescents, or the more recent onset of illness for adolescent patients (Workgroup for Classification of Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents, 2007).

Evidence from randomized controlled trials for adults with BN indicate that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is effective, and consistently superior to pharmacological therapy and other forms of psychotherapy, at least in the short-term (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004; Wilson, Grilo, & Vitousek, 2007). Controlled data are limited for adolescents with BN, but a study by Schmidt and colleagues (2007) found cognitive-behavioral self-help to be effective in reducing binge eating and vomiting symptoms. However, improvements to CBT are needed, as post-treatment abstinence rates for binge eating and purging are only 30-50% (Wilson, 1996; Wilson & Fairburn, 2007). Fairburn and colleagues (2003) proposed an enhanced form of CBT (CBT-E), derived from earlier forms of CBT for BN (Fairburn, Marcus, & Wilson, 1993), but intended to be applied to all outpatients with eating disorders regardless of DSM-IV diagnosis. This enhanced form of CBT also includes the potential for tailoring treatment to an individual patient by adding modules to target other maintaining mechanisms, such as interpersonal functioning, mood intolerance, core low self-esteem, or clinical perfectionism (Fairburn et al., 2003). Early behavior therapy included a similar focus on broader maintaining mechanisms (e.g., interpersonal conflicts; e.g., Lazarus, 1971), although as behavioral treatments evolved to incorporate cognitive components, the majority of CBT applications developed disorder-specific manuals (e.g., Fairburn, Marcus, & Wilson, 1993; Pike et al., 2003).

The enhanced CBT, as manualized by Fairburn (2008), is a 20-40-session treatment emphasizing the core psychopathology of overvaluation of body weight, shape, and their control. Briefly, for individuals who are not significantly underweight, the first phase of CBT-E includes twice-weekly appointments in response to data showing the importance of early response to treatment in CBT (Fairburn, Agras, Walsh, Wilson, & Stice, 2004; Wilson, Fairburn, Agras, Walsh, & Kraemer, 2002), over a four week period. In addition to developing a therapeutic relationship and creating a personalized formulation for treatment, the first phase of CBT-E focuses on helping patients to develop a regular pattern of eating and weighing. The second phase of treatment, which occurs during the fifth and sixth weeks (eighth and ninth sessions) is intended as a brief stage where the therapist and patient review progress to date, note any barriers to change, adapt the treatment formulation, and plan for the next CBT-E sessions (Fairburn, 2008). From the tenth to seventeenth weeks (seventh-fourteenth sessions), patients are involved in the third phase of treatment, with the primary aim of addressing factors that maintain the eating disorder. In the “focused” version of CBT-E (CBT-Ef), this portion of treatment addresses reducing eating disorder psychopathology, whereas the “broad” version (CBT-Eb) includes modules to address other factors that may be maintaining the eating disorder (interpersonal functioning, core low self-esteem, or clinical perfectionism). The final phase consists of three sessions over the last six weeks of treatment, and serves as a means for maintaining changes and relapse prevention (Fairburn, 2008).

Although CBT-E is a treatment for adults, adaptations for adolescents are also suggested by Cooper and Stewart (2008). Justification for the application of CBT-E to younger patients, include: (1) similarities in clinical features between adults and adolescents and clinical experience, (2) data suggesting the efficacy of CBT for youth with other disorders, (3) the pertinence of the issue of “control” among younger patients, which is a focus of CBT-E, (4) the importance of increasing motivation when treating adolescents, a topic explicitly addressed in CBT-E, and (5) the fact that this form of treatment is appropriate for all eating disorders (Cooper & Stewart, 2008).

A number of principles underlie modifications to CBT-E for adolescents, and Cooper and Stewart (2008) identify the need to enhance autonomy and personal responsibility on the basis of adolescents' developmental stage and cognitive development, the importance of considering enhancing motivation to change, addressing peer relationships, involving schools, appreciating possible medical complications, and involving others in treatment (e.g., family, multidisciplinary team), as important considerations for younger patients. Although CBT-E for adolescents includes the same phases of treatment and general content as for adults, specific adaptations are suggested by Cooper & Stewart (2008) to address the principles described above. For example, Cooper & Stewart (2008) encourage joint meetings with the patient, parents, and therapist such that the adolescent can receive assistance with some of the more challenging aspects of treatment (e.g., purchasing avoided foods). In addition, they emphasize the importance of engaging adolescents in treatment, the need to collaborate on the development of the treatment formulation, and considering developmental adaptations to the usual elements of CBT-E such as self-monitoring, weekly weighing, and regular eating (Cooper & Stewart, 2008).

A recent study reported the results of a trial comparing patients with eating disorders randomized to a wait-list or one of two forms of the 20-session CBT-E described above: (1) focused CBT-E addressing only eating disorder psychopathology (CBT-Ef), or (2) broad CBT-E with a focus on additional maintaining mechanisms (CBT-Eb; Fairburn et al., 2009). Individuals in the CBT-Eb and CBT-Ef groups improved significantly in comparison to those patients assigned to the waiting-list, who showed little improvement. No significant differences were observed between the groups receiving CBT-Eb and CBT-Ef at the end of treatment. Thus, initial data from the Fairburn et al. (2009) suggest the efficacy of treating normal-weight patients with EDNOS or individuals with BN using CBT-E. As the Fairburn et al. (2009) study included only individuals who were 18 or older, this study does not provide information about applying CBT-E to younger populations.

This case report describes the use of enhanced CBT including a focus on additional maintaining mechanisms (CBT-Eb) with an adolescent presenting for treatment with EDNOS and comorbid attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). This case began as an unsuccessful attempt at family therapy, where the underlying dysfunction exacerbated symptoms and demoralized the family. As described below, CBT-Eb allowed for dealing with specific vulnerabilities related to the eating disorder that ultimately improved family functioning.

Patient Characteristics

Kaitlin1 was a Russian-born 16 year old female living at home with her younger brother (age 13) and biological parents. At intake, Kaitlin's percentile for body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) based on age and gender was 19 (Kuczmarski et al., 2002), indicating that her weight was not consistent with AN. Records obtained from her pediatrician indicated that her BMI was consistently between the 10th and 20th percentile throughout her development. By clinical interview, Kaitlin reported loss of control over eating approximately 24 times per week and 35 episodes of purging per week. Kaitlin experienced a sense of loss of control while eating a single item of food when the food was unplanned or contained a large proportion of carbohydrates. Her purging episodes would follow these subjective binge episodes (SBEs), but also occurred when her mood was particularly low, or she generally felt ‘out of control’ of some other aspect of her life. She denied any laxative or diet pill use. Her exercise was infrequent, but when it occurred, it was compulsive in nature. In addition, Kaitlin reported notable body image disturbances, believing that she was fat and that her appearance was “appalling” to others. As is common among patients with eating disorders, she alternated between weighing herself multiple times per day and avoiding the scale altogether.

Katlin also reported significant mood swings, varying from happy and easy going to angry and depressed, but although she endorsed these symptoms, Kaitlin did not meet full criteria for any specific DSM-IV mood disorder. Her parents also described regular angry outbursts. Kaitlin's sleeping pattern was irregular, as she would often wake in the middle of the night to binge and/or purge, which resulted in only an average of 3-4 hours of continuous sleep per night and approximately 7 hours total. Katlin was diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in 1st grade and since that time, she had been treated primarily with medication (e.g. methylphenidate). When she presented for treatment, she was prescribed 40 mg/day of Straterra (atomoxetine).

Family Dynamics

At the onset of her eating disorder, Kaitlin's parents were not overly concerned by her symptoms, and some behaviors were even viewed positively by her family as attempts to “get healthy.” For example, Kaitlin's parents addressed her irregular but compulsive exercise by offering to provide her with a personal trainer for more consistency in her physical activity, and responded to her out of control eating by suggesting a consultation with a nutritionist to help Kaitlin eat more healthy foods. However, as her eating disorder continued, her symptoms exacerbated problems within the family.

Kaitlin's father was the primary advocate for adopting more “healthy” behaviors, and a number of his suggestions supported the maintenance of Kaitlin's eating disorder, which was a source of frustration for Kaitlin. Kaitlin's father would point out inconsistencies in her eating and exercise as a means of motivating his daughter to change, but she would experience these comments as painful and shaming, become upset, and verbal conflicts would often ensue. Her mother typically mediated these arguments, and believed that if Kaitlin were just able to lose “a few pounds,” she would be happy and her problematic behaviors and the fighting with her father would subsequently decrease. Different responses to Kaitlin's eating disorder also reflected divergent parenting styles, with her father acting as a motivating and energizing force with a focus on achievement in the family, and her mother providing a calming presence, support, and nurturance. At the start of treatment, the family was particularly destabilized due to the frequency of fighting between Kaitlin and her father, and her mother and brother were unable to successfully work to mediate the conflicts.

Rationale for Utilizing CBT-E

The ability to simultaneously address Kaitlin's symptoms and other maintaining mechanisms using an evidence based treatment (CBT-Eb) provided a distinct advantage in treatment planning and execution. Kaitlin's weight was not consistent with a diagnosis of DSM-IV AN, and she described binge eating episodes where she did not consume “an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during a similar period of time and under similar circumstances” (APA, 1994), which meant that she also did not meet criteria for a diagnosis of DSM-IV BN. Thus, she was assigned a diagnosis of an EDNOS; however, her symptoms were consistent with a syndrome labeled “purging disorder” (Keel, 2007; Keel, Haedt, & Edler, 2005). Although the definition of this syndrome varies (Keel, 2007), it is typically characterized by recurrent episodes of purging either with or without SBEs. The clinician (TBH) decided to use CBT-Eb with Kaitlin as this type of treatment is efficacious for patients with BN and normal-weight EDNOS, and purging disorder shares an important behavioral target with BN (purging).

Treatment Course

Kaitlin attended 29 sessions of treatment over 9 months. When Kaitlin and her family first presented, they began a course of Maudsley family therapy (MFT), an empirically-supported treatment for adolescents with BN (le Grange, Crosby, Rathouz, & Leventhal, 2007). Consistent with this approach as described for adolescents with BN (le Grange & Lock, 2007), the first session following an intake assessment primarily involves raising the anxiety of the parents and placing them in charge of regulating their child's eating. However, it was very difficult to complete the session. Kaitlin and her parents frequently argued, about the eating symptoms and other unrelated issues, which was indicative of a significant degree of expressed emotion (Hooley, 2007), typically in the form of parental criticism (Eisler, Dare, Hodes, Russel, Dodge, & Le Grange, 2000). By the end of the first session of MFT, both Kaitlin and her father were very angry and refused to participate in the treatment as designed.

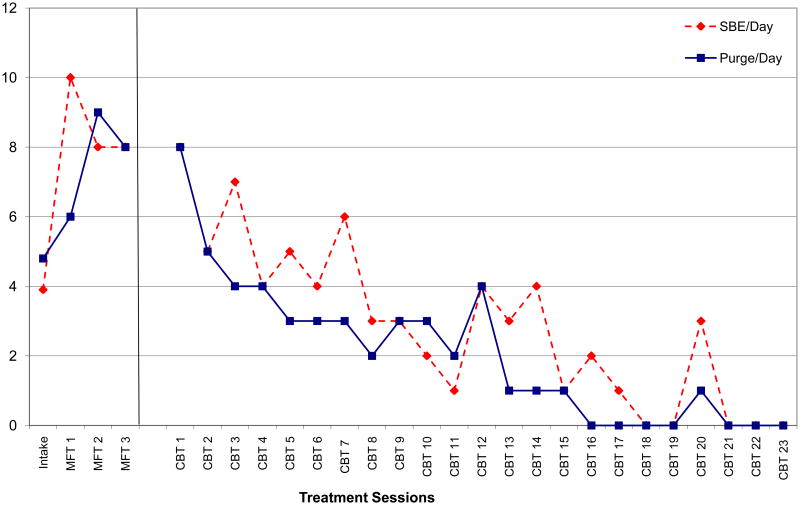

As outlined in the MFT manual (le Grange & Lock, 2007), a decision was made to proceed in split format whereby the therapist would meet with Kaitlin and her family separately, each of whom would be allotted half of the session. Over the course of 3 split sessions of MFT, Kaitlin's rate of vomiting accelerated, from 3-5 times per day to 6-8 times per day (see Figure 1). Kaitlin believed the increase in vomiting was related to conflicts with her parents that occurred multiple times per day. Based on existing evidence from empirical studies of MFT (Eisler et al., 2000), the degree of expressed emotion among the family was deemed detrimental to continuing with this form of therapy. The therapist recommended a course of individual CBT-E, and despite the problems during MFT, Kaitlin was motivated to eliminate her eating disorder symptoms and agreed to try this type of treatment.

Figure 1. Change in Frequency of Daily Subjective Bulimic Episodes (SBE) and Purging Over the Course of Family Therapy (MFT) and Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT).

Phase I of treatment (sessions 1-7, weeks 1-4)

The transition to CBT-E began with a formal agreement on a case formulation between Katlin and her therapist, which was developed from observations over the initial MFT treatment sessions and assessment. At this point, Kaitlin indicated that she believed the therapist understood her eating disorder and many of the proximal triggers for her eating disordered behavior. In both CBT for BN (Fairburn, et al., 1993) and CBT-E (Fairburn, 2008), self-monitoring is initiated in the first session. Kaitlin's problems related to remembering tasks and general inattention exacerbated her difficulties with keeping food records. To help keep this therapy assignment present in her mind, Kaitlin and her therapist created several environmental “triggers” for self-monitoring. First, Kaitlin created a phrase that reminded her of the assignment and entered it as her cell phone “name” such that every time she checked her cell phone she would be reminded to self-monitor. Second, between-session phone check-ins were instituted as a means to problem-solve around self-monitoring. Phone contact occurred daily for the first week, but transitioned from therapist-initiated phone calls, to messages left by Kaitlin on the therapist's voicemail noting her progress with self-monitoring. Between-session contacts were intended to reinforce any self-monitoring attempts, normalize difficulties with monitoring, and continue to support the assignment of monitoring after every eating and purging episode. Thirdly, Kaitlin's mother was recruited to help with her assignments. Kaitlin and her mother had previously agreed on a system of rewards for schoolwork whereby Kaitlin received a small reward if she finished all of her work for the week. Rewards usually consisted of money for a manicure, to download music, or to go to the movies. Kaitlin and her mother decided to include assignments from therapy into this established reward system. The goal was to provide parental involvement in the CBT-E while maintaining a developmentally appropriate degree of autonomy for Kaitlin, similar to that described by Cooper and Stewart (2008).

After the initiation of self-monitoring, Kaitlin was assigned the task of regular eating, or consuming three planned meals and two snacks per day, with no more than four hours between meals/snacks. Regular eating was particularly difficult for Kaitlin at school because her friends generally skipped lunch, and she was very sensitive to appearing different from her friends. On the weekends, Kaitlin ate a mid-day meal without a problem. To address this obstacle, Kaitlin agreed to conduct a behavioral experiment of eating lunch with one of her friends on the weekend and evaluating her friend's response. She agreed to use this experience to subsequently make another hypothesis about how her friends would respond to her decision to eat lunch at school. This pattern set the stage for a number of behavioral experiments targeting obstacles to regular eating and eventually the incorporation of forbidden foods.

To address her vomiting episodes, the therapist reviewed Kaitlin's self-monitoring records to identify triggers, most of which involved eating foods that she tried to exclude from her diet (forbidden foods), or a sensation of fullness/fatness after eating. Other triggers included mood swings, early waking, and interpersonal conflict with her parents or friends. Self-monitoring alone reduced her purging episodes; however, the primary intervention was to delay the use of purging as a coping mechanism. Kaitlin's mother was again recruited to provide rewards for any delays in her purging. Delays became progressively longer from session to session, with the goal of reaching 1 hour between the trigger and purging. Simultaneously, Kaitlin began utilizing alternatives to purging, which were introduced as a form of ‘self-care’. In some cases these activities were preventative (i.e., planning to do a yoga tape if she awoke early in the morning) or instituted at the onset of the trigger (i.e., listening to a song from her favorite band).

The therapist also instituted regular weighing in the initial phase of CBT-E

Initially, Kaitlin was weighed in session after her parents removed the scale from her bathroom, but she could not tolerate seeing her weight at this time, particularly after having experienced an increase in SBEs during the initial course of family therapy. Psychoeducation about weight was provided, but this information did little to reduce Kaitlin's anxiety about the possibility of weight gain. Kaitlin was asked to step on the scale in session without looking at the weight and remain on the scale until her anxiety decreased. This process was repeated at each session, and the amount of exposure was gradually increased until the end of phase I, when Kaitlin could weigh herself in session and tolerate seeing her weight.

Phase II (sessions 8-9, week 5-6)

The significant decrease in both Kaitlin's binge eating and purging episodes during the first phase of CBT-E is illustrated in Figure 1. As outlined in the CBT-E manual (Fairburn, 2008), after the first phase of treatment, the focus of the sessions shifted to reformulating Kaitlin's eating disorder based on the progress she had made to that point. A separate visit was also held with her parents to discuss the changes in Kaitlin's symptoms during the prior six weeks and to incorporate their impressions of the maintaining mechanisms for her remaining symptoms into the treatment plan. In the reformulation process, two major obstacles that prevented Kaitlin from achieving abstinence from her eating disorder were identified by Kaitlin's parents and her own observations. She continued to fight frequently with her family and feared being disliked by her friends. Furthermore, her mood swings complicated her interpersonal relationships with both family and friends and reflected a general difficulty tolerating affective states. Based on this re-formulation, the choice was made to implement CBT-Eb including a focus on mood-related changes in eating and interpersonal functioning. The mood intolerance component of CBT-Eb and the symptoms. interpersonal module were selected because these areas significantly impacted Kaitlin's ability to achieve abstinence from her eating disorder symptoms.

Phase III (sessions 10-24, weeks 7-21)

In practice, once additional maintaining mechanisms and modules are chosen in CBT-Eb, half of the session is allotted for addressing ongoing bulimic behaviors, and half for a modular treatment (Fairburn, 2008). This format was also used when addressing mood intolerance, and Kaitlin continued to build upon the progress she made in the initial phases of treatment. A series of assignments were developed for dealing with mood intolerance, including: alternative behaviors (e.g., brushing her dog when she felt sad), slowing down and observing emotions (e.g., distancing herself from her negative mood and observing how long it lasted), and making the choice to behave in a manner that was the opposite of what she felt at the moment (e.g., reaching out to a friend when she felt like withdrawing from social contact). Reinforcement from the therapist via phone check-ins was available to Kaitlin during this time as a form of shaping behavior, but only prior to a binge eating or purging episode. When the patient called after an episode, the call was not returned until the next day and then was only limited to a risk assessment. Kaitlin's mother continued to provide small reinforcements for completing therapy assignments, but solely for finishing assignments and rewards were not contingent on whether the assignments had an appreciable impact on symptoms.

The remaining sessions addressed binge eating and purging and interpersonal problems. Reductions in parental conflict, particularly with her father, had already occurred as a result of Kaitlin's work on mood tolerance. As Kaitlin learned different ways to deal with her moods, her father began to adopt some similar strategies, which allowed the sessions to focus on residual interpersonal deficits. Two specific behaviors often led to interpersonal conflict. The first was Katilin's tendency to be very critical, particularly about the shape and/or weight of her friends. While she felt that her friends exhibited similar standards and said she “preferred the honesty” of her friends about this topic, the practice usually only resulted in hurt feelings, gossiping, and interpersonal threats (e.g., ignoring friends, recruiting friends to shame other friends, and public humiliation). Together, Kaitlin and her therapist discussed strategies for eliminating these behaviors and replacing them with more pro-social behaviors. In some instances, role plays were used to rehearse specific responses to criticism and others' interpersonal threats. These interventions had the unintended effect of improving Katlin's relationship with her father. While his interactions with her could still be distressing, her responses limited the degree of conflict and ultimately improved the relationship. Over the course of this module, Kaitlin identified two friendships that she felt were particularly problematic and most of the work targeted these relationships. As individual treatment with Kaitlin had been successful in helping to increase stability within the family to this point, the work on interpersonal relationships was primarily patient-oriented, and switching to a more traditional family therapy was not considered.

By the end of this phase of treatment, Kaitlin's purging had ceased and she no longer reported experiencing a sense of loss of control around food. However, Kaitlin had body image concerns that persisted, and while she was able to tolerate this disturbance, she would still criticize her appearance and generally believed herself to be fat. She rationalized these cognitions using the idea that most people had similar thoughts, and she was not going to let the thoughts interfere with her life. The interventions for body image described in CBT-Eb involve reducing checking and avoidance behaviors and diversifying self-evaluation beyond shape and weight. These interventions were not used explicitly during this course of treatment, although Kaitlin had made some improvements in this area through changes in her other symptoms. As she spent less time engaged in her eating disorder, many of these changes occurred naturally.

Phase IV (sessions 25-29, weeks 22-36)

The final phase of treatment included a transition from weekly to bimonthly sessions, and Kaitlin practiced becoming her own therapist. As a reward for her work on her eating disorder during the prior 21 weeks, Kaitlin was given permission to attend summer camp, an opportunity she was excited about since a childhood friend was also planning to attend to the same camp. During this phase, Kaitlin began initiating her own goals for treatment and reporting them to her therapist. She created a system to provide her own reminders about the skills she needed to employ, using her cell phone to help her remain mindful of certain interventions. For example, she created a system called ‘random acts of kindness’ where she would engage in some form of a ‘good deed’ independent of her mood. This good deed could be as simple as telling her mother that she loved her, or sending a friend a complementary text message.

The final few sessions focused on relapse prevention while reviewing progress made during treatment, and specific plans were designed to handle lapses in symptoms and thresholds for seeking help. A written relapse prevention plan was developed in collaboration with Kaitlin, and once a final version agreed upon by therapist and patient, a copy was given to both the patient and her parents. If any episodes of binge eating or purging occurred, the plan involved re-initiating self-monitoring, seeking helpful alternatives, and asking others (e.g., her mother) for help. Kaitlin only had one lapse during this phase, triggered by a friend calling her fat. Although some residual concerns about shape and weight in combination with similar interpersonal situations might have increased Kaitlin's likelihood for relapse, she was able to utilize this plan without assistance from her therapist and described the experience as a success at her final session, and the treatment was concluded.

Strengths and Challenges to an Individual CBT-Eb Treatment Approach with an Adolescent

This case study illustrates that it is possible to successfully use CBT-Eb with developmentally appropriate adaptations in the treatment of a young patient with an EDNOS diagnosis, as suggested by Cooper and Stewart (2008). Kaitlin's treatment was similar to the adapted approach described by Cooper and Stewart (2008) by involving the patient's mother from the beginning of treatment through brief conjoint meetings, the creation of a treatment formulation, regular consultation with the patient's medical providers, the use of real-time self-monitoring, in-session weighting, age appropriate psychoeducation regarding eating and weight problems, and regular eating. The treatment was longer than described by Cooper and Stewart (2008) for adolescents who are not significantly underweight, but the additional sessions were considered necessary for material focused on mood intolerance and interpersonal functioning to be implemented in a manner appropriate for Kaitlin's developmental stage. In addition, the therapist focused less on engaging the patient in treatment and motivation to change than might be expected with other adolescents receiving CBT-E. Kaitlin entered treatment highly motivated to eliminate her symptoms, and continued to respond to the behavioral reinforcements throughout the course of therapy. Finally, the therapist employed between-session phone check-ins for reinforcement and shaping, and to accommodate some of Kaitlin's ADHD symptoms, and used a form of exposure to decrease her anxiety related to in-session weighing.

At this time, the lack of data for adolescents beyond a single case is a significant challenge to evaluating the utility of enhanced cognitive behavioral approaches for younger patients, or purging disorder in particular. Similarly, limited information is available to inform the treatment of adults with an EDNOS. However, the positive results of this case study are consistent with those reported by Fairburn and colleagues (2009) in a sample of normal-weight adults with an EDNOS, and a study by Schmidt and colleagues (2007) using a guided self-help form of CBT for adolescents with BN or EDNOS, which included normal-weight individuals who reported inappropriate compensatory behaviors without binge eating. For future research, possible strengths of CBT-E for youth include: the ability to treat patients with EDNOS, including adolescents, given their overwhelming presence in clinical populations, and the possibility of increasing the ease of disseminating an empirically-supported treatments for eating disorders, because training in only one manual would be required.

This case introduces some interesting clinical questions related to the family system, in particular, the primary involvement of Kaitlin's mother in the monitoring and reinforcement process, and the effect of the choice to discontinue, and not resume, family therapy. There were potential disadvantages to only involving Kaitlin's mother in CBT-Eb. It was possible that because of her more primary role in the treatment, Kaitlin's mother would feel overburdened by an increase in her responsibilities within the family, and there was a risk for more miscommunication between Kaitlin and her father due to his limited involvement in the treatment. Kaitlin's father could have continued to reinforce her eating disorder symptoms because he did not participate in developing therapy assignments, or might have even undermined contingencies agreed upon by Kaitlin and her mother. Among the advantages to primarily involving Kaitlin's mother were reducing stress within the family due to fewer conflicts between Kaitlin and her father, and allowing Kaitlin greater autonomy to manage and change her eating disorder symptoms.

Either MFT or a traditional form of family therapy could have been delivered conjointly or resumed following Kaitlin's individual treatment. It is not possible to know whether augmenting or sequencing family therapy would have amplified the gains Kaitlin experienced from CBT-Eb. However, traditional family therapy could have addressed issues such as the disparate parenting styles between Kaitlin's mother and father, or helped in identifying her symptoms as a means for communicating basic needs to her parents. The initial sessions of MFT also helped to externalize Kaitlin's symptoms, and reduced the tendency for the family to blame her for the eating disorder, gains that might have continued with additional MFT. One potential concern with utilizing conjoint MFT is the focus on empowering both parents to assist with symptom control, which could have increased the pressure on Kaitlin's mother to manage both the parenting style of Kaitlin's father's and Kaitlin's reactions to family conflicts. It is possible that once Kaitlin had experienced some relief from her eating disorder, she may have been better equipped to handle this approach, but the use of individual therapy alone produced a clinically meaningful change in her symptoms.

The results of this case highlight a few important concepts. First, assessing the degree of expressed emotion in the home environment is particularly important when a clinician is making initial decisions for how to proceed with an adolescent. Attention should be paid to the way in which individuals in the family respond to one other when they are upset or frustrated. When a high degree of expressed emotion is present, CBT-E may offer advantages over MFT. Secondly, the presence of mood intolerance and interpersonal problems can affect an adolescent's functioning independent of his or her eating disorder. For Kaitlin, mood and interpersonal issues exacerbated her eating disorder, but also caused distress independent of her eating pathology, which contributed to the difficulty in assigning specific comorbid diagnoses. CBT-Eb offers a means for targeting these other issues along with the eating disorder, which can improve the patient's bulimic symptoms, overall affect, and family or peer relationships. Finally, the application of a successful individual treatment helped create an environment that reinforced positive change within the family and greatly improved the overall quality of their relationships.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Sysko is supported, in part, by DK088532-01A1 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Dr. Hildebrandt is supported, in part, by DA024043-01 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse

Footnotes

Changes were made to identifying information in this case to protect patient confidentiality

Contributor Information

Robyn Sysko, New York State Psychiatric Institute, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University.

Tom Hildebrandt, Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Z, Stewart A. CBT-E and the younger patient. In: Fairburn CG, editor. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy KT, Celio Doyle A, Hoste RR, Herzog DB, le Grange D. Eating disorder not otherwise specified in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:156–164. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815cd9cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler I, Dare C, Hodes M, Hodes M, Russell G, Dodge E, et al. Family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa: The results of a controlled comparison of two family interventions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2000;41:727–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Agras WS, Walsh BT, Wilson GT, Stice E. Prediction of outcome in bulimia nervosa by early change in treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:2322–2324. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Bohn K, O'Connor ME, Doll HA, Palmer RL. The severity and status of eating disorder NOS: Implications for DSM-V. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:1705–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, O'Connor ME, Bohn K, Hawker DM, et al. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: A two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:311–319. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:509–528. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Marcus MD, Wilson GT. Cognitive behaviour therapy for binge eating and bulimia nervosa: A comprehensive treatment manual. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: Nature, assessment and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 361–404. [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM. Expressed emotion and relapse of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:329–352. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK. Purging disorder: Subthreshold variant or full-threshold eating disorder? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:S89–S94. doi: 10.1002/eat.20453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Haedt A, Edler C. Purging disorder: An ominous variant of bulimia nervosa? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;38:191–199. doi: 10.1002/eat.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: Methods and development. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Statistics. 2002;11:1–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus AA. Behavior Therapy and Beyond. New York: McGraw Hill; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Le Grange D, Crosby RD, Rathouz PJ, Leventhal BL. A randomized controlled comparison of family-based treatment and supportive psychotherapy for adolescent bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1049–1056. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.9.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grange D, Lock J. Treating bulimia in adolescents: A family-based approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. NICE Clinical Guideline No. 9. London: NICE; 2004. Eating Disorders—Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa and Related Eating Disorders. http://www.nice.org.uk. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls D, Chater R, Lask B. Children into DSM don't go: A comparison of classification systems for eating disorders in childhood and early adolescence. The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;28:317–324. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200011)28:3<317::aid-eat9>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike KM, Walsh BT, Vitousek K, Wilson GT, Bauer J. Cognitive behavior therapy in the posthospitalization treatment of anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:2046–2049. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricca V, Mannucci E, Mezzani B, Di Bernardo M, Zucchi T, Paionni A, et al. Psychopathological and clinical features of outpatients with an eating disorder not otherwise specified. Eating and Weight Disorders. 2001;6:157–65. doi: 10.1007/BF03339765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt U, Lee S, Beecham J, Perkins S, Treasure J, Yi I, et al. A randomized controlled trial of family therapy and cognitive behavior therapy guided self-care for adolescents with bulimia nervosa and related disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:591–598. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.4.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner H, Bryant Waugh R. Eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS): profiles of clients presenting at a community eating disorder service. European Eating Disorders Review. 2004;12:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT. Treatment of bulimia nervosa: When CBT fails. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:197–212. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Fairburn CG. Treatments for Eating Disorders. In: Nathan PE, Gorman JM, editors. Treatments That Work. 3rd. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. pp. 579–610. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS, Walsh BT, Kraemer H. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa: Time course and mechanisms of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:267–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. American Psychologist. 2007;62:199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workgroup for Classification of Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Classification of child and adolescent eating disturbances. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:S117–S122. doi: 10.1002/eat.20458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]