Abstract

Blossoms are important sites of infection for Erwinia amylovora, the causal agent of fire blight of rosaceous plants. Before entering the tissue, the pathogen colonizes the stigmatic surface and has to compete for space and nutrient resources within the epiphytic community. Several epiphytes are capable of synthesizing antibiotics with which they antagonize phytopathogenic bacteria. Here, we report that a multidrug efflux transporter, designated NorM, of E. amylovora confers tolerance to the toxin(s) produced by epiphytic bacteria cocolonizing plant blossoms. According to sequence comparisons, the single-component efflux pump NorM is a member of the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion protein family. The corresponding gene is widely distributed among E. amylovora strains and related plant-associated bacteria. NorM mediated resistance to the hydrophobic cationic compounds norfloxacin, ethidium bromide, and berberine. A norM mutant was constructed and exhibited full virulence on apple rootstock MM 106. However, it was susceptible to antibiotics produced by epiphytes isolated from apple and quince blossoms. The epiphytes were identified as Pantoea agglomerans by 16S rRNA analysis and were isolated from one-third of all trees examined. The promoter activity of norM was twofold greater at 18°C than at 28°C. The lower temperature seems to be beneficial for host infection because of the availability of moisture necessary for movement of the pathogen to the infection sites. Thus, E. amylovora might employ NorM for successful competition with other epiphytic microbes to reach high population densities, particularly at a lower temperature.

Fire blight, caused by the enterobacterium Erwinia amylovora (Burrill) Winslow et al., is a necrotrophic disease of members of the Rosaceae, and it has economic importance in the cultivation of apples and pears (10). The initial symptom of fire blight is water soaking, which is followed by wilting and rapid necrosis that leaves infected tissue with a scorched, blackened appearance. Migration of the pathogen through cortical parenchyma and the xylem vessels into all parts of the plant can lead to loss of entire trees (52).

E. amylovora uses blossoms as the main route of infection; however, other natural openings or wounds also provide entry into a plant (11). The pathogen multiplies primarily on stigmas, which have a moist and nutrient-rich surface. It can reach population densities of 106 to 107 CFU per healthy flower (47). The establishment of such large epiphytic populations is a precondition for dissemination from colonized blossoms to noncolonized blossoms by rain or pollinating insects and for successful infection of a host plant. The pathogen does not infect a stigma or style directly but invades the host tissue through nectarthodes located in the hypanthium at the base of the pistil (57, 58). Principally rain or heavy dew washes bacterial cells from the stigma into the floral cup and allows migration to the natural openings.

During the course of infection, the pathogen is exposed to plant-borne antimicrobial compounds termed phytoalexins, and a study of this has recently been conducted in our laboratory (6). Additionally, establishment of an E. amylovora population on the stigmatic surface is influenced by other epiphytic microorganisms. In such a microbial community the competition for space and nutrient resources and the production of antibiotics are considered to be the principal mechanisms used by indigenous microbes to antagonize each other.

Biological control of fire blight has been focused on the interaction between antagonistic epiphytes and E. amylovora on stigmatic and hypanthial surfaces of pear or apple blossoms (22). In particular, the bacterial species Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pantoea agglomerans have been investigated for the ability to prevent an increase in E. amylovora population size and subsequent floral infection (23, 24, 36, 53, 59). Both of these epiphytes are found frequently on apple and pear flowers. A microscopy study of the interaction between P. agglomerans and E. amylovora demonstrated that these two species occupy the same sites on the stigmas of apple flowers (17). Moreover, P. agglomerans strains synthesize antibiotics which inhibit growth of E. amylovora in vitro (12, 60). This antibiosis may be the reason for the competitive superiority of P. agglomerans in the interaction with the fire blight pathogen. However, not all antibiotic-producing strains of P. agglomerans are efficient antagonists that prevent colonization and infection of a host plant by E. amylovora. In response to the antibiotic metabolites of epiphytes, the pathogen may have developed resistance mechanisms.

Bacteria use various strategies to combat antibiotics, such as enzymatic inactivation, alteration of the target structure, and reduced uptake (54). Another mechanism involves membrane-bound efflux pumps capable of transporting toxins. In contrast to specific resistance mechanisms, a large number of so-called multidrug efflux transporters have been found to recognize and expel a broad range of structurally unrelated compounds from the cell (4, 51).

In bacteria, multidrug efflux is mostly mediated by secondary transporters which utilize the transmembrane electrochemical gradient, typically the proton motive force, for this process. Four cytoplasmic membrane transport protein families that include multidrug efflux systems of bacteria have been described: the major facilitator superfamily (38, 43), the resistance-nodulation-cell division superfamily (50), the small multidrug resistance family (39), and the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family (5). In phytopathogenic and plant-associated bacteria only a small number of multidrug efflux pumps, classified in the major facilitator and resistance-nodulation-cell division superfamilies, have been characterized so far.

Recently, the AcrAB multidrug efflux system of E. amylovora was investigated in detail in our laboratory and was found to confer tolerance to plant-borne phytoalexins, such as phloretin, and to be required for virulence of the pathogen in apples (6). In the present study, we identified and characterized the first multidrug efflux transporter belonging to the MATE family in a plant-pathogenic bacterium. Here we describe cloning of the norM gene from E. amylovora, which codes for a protein significantly homologous to NorM of Escherichia coli and Vibrio parahaemolyticus (33, 34). It has been demonstrated that this transporter confers resistance to several hydrophobic cationic antibiotics. Mutation of norM in E. amylovora significantly reduced tolerance to toxins produced by epiphytic P. agglomerans strains isolated from apple and quince blossoms. Because temperature affects epiphytic growth and infection of a host plant by E. amylovora, the promoter activity of norM was analyzed by using a transcriptional fusion with the reporter gene uidA in vitro at 18 and 28°C.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2 (also see Tables 4 and 5). E. amylovora strains and strains of related plant-associated bacteria were cultured at 28°C on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or asparagine minimal medium 2 (AMM2). AMM2 contained (per liter of demineralized water) 10 g of fructose, 4 g of l-asparagine, 12.8 g of Na2HPO4 · 7H2O, 3 g of K2HPO4, 3 g of NaCl, 0.2 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.25 g of nicotinic acid, and 200 μg of thiamine. Where indicated below, antibiotics were added to the media. E. coli strains DH5α and KAM3 (33) were used as cloning hosts. KAM3, a derivative of E. coli TG1 with a deletion in the chromosomal acrAB genes, was also used for drug susceptibility testing. E. coli cells were routinely maintained at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg of ampicillin per ml, 25 μg of chloramphenicol per ml, and 25 μg of kanamycin per ml if necessary. Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm.

TABLE 1.

E. coli and E. amylovora strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80 lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 44 |

| TG1 | subE hsdΔ5 thi Δ(lac-proAB) F′[traD36 proAB+lacIqlacZΔM15] | 44 |

| KAM3 | AcrAB mutant of TG1 | 33 |

| S17-1 | thi pro hsdR−hsdM+recA RP4 2−Tc::MU-Km::Tn7(Tetr/Smr) | 56 |

| S17-1 λ-pir | λ-pir lysogen of S17-1 | 56 |

| E. amylovora strains | ||

| Ea1189 | Wild type | GSPBa |

| Ea225 | Spr, norM mutant carrying mini-Tn5 in the norM gene | C. Goyer |

| Ea1189-34 | Kmr, norM mutant carrying chloramphenical resistance cassette in the norM gene | This study |

GSPB, Göttinger Sammlung phytopathogener Bakterien, Göttingen, Germany.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pBluescript II SK(+) | Apr, ColE1 origin | Stratagene |

| pBBR1MCS | Cmr, ColE1 origin | 26 |

| pBBR1MCS-2 | Kmr, ColE1 origin | 27 |

| pCAM140 | Smr Spr Apr, R6K origin, mTn5SSgusA40 | 56 |

| pCAM140-MCS | Apr, R6K origin, pCAM140 derivative without mini-Tn5, contains the multiple cloning site of pBluescript II SK(+) | This study |

| pfd4 | Cmr Kmr, fd origin | 13 |

| pBBR.nor6 | Cmr, contains a 4.4-kb PstI fragment carrying norM region of E. amylovora cloned in pBBR1MCS | This study |

| pBBR.norM | Cmr, contains a 3.2-kb ClaI fragment derived from pBBR.nor6 in pBBR1MCS | This study |

| pBBR2.norM | Kmr, contains a 3.2-kb ClaI fragment derived from pBBR.nor6 in pBBR1MCS-2 | This study |

| pMEC2 | Apr, contains a 2.5-kb SspI-SphI fragment carrying the norM region of E. coli cloned in pBR322 | 33 |

| pBBR.norM.Ec | Cmr, contains a 2.4-kb HindIII-XbaI fragment derived from pMEC2 in pBBR1MCS | This study |

| pBlue.norM | Apr, contains a 3.2-kb ClaI-PstI fragment derived from pBBR.nor6 in pBluescript II SK(+) | This study |

| pBlue.norM-Cm | Apr Cmr, insertion of Cmr cassette in EcoRV site of norM in pBlue.norM | This study |

| pCAM.acr-Km | Apr Kmr, contains a 5.3-kb SpeI-BamHI fragment derived from pBlue.norM-Cm in pCAM140-MCS | This study |

TABLE 4.

Growth inhibition of the E. amylovora wild type and norM mutant caused by different P. agglomerans strains

| P. agglomerans strain or antibiotic | Host | Source | Diam of inhibition zone (mm)a

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ea1189

|

Ea1189-34 (pBBR1MCS-2)

|

Ea1189-34 (pBBR2.norM)b

|

||||||

| 18°C | 28°C | 18°C | 28°C | 18°C | 28°C | |||

| Bel2/7 | Apple | Eisenroth | 0 | (25)c | (23) | 26 | 0 | 0 |

| Bel3/1 | Apple | Eisenroth | 0 | (25) | 14 (22) | 26 | 0 | 0 |

| MR4/1 | Apple | Marburg | 0 | (24) | 14 (22) | 26 | 0 | 0 |

| MR5/1 | Apple | Marburg | 0 | (25) | 16 (22) | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| QT2/5 | Quince | Marburg | 0 | (25) | 16 (24) | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Spectinomycin (5 mg/ml) | 20 | 28 | 18 | 27 | 18 | 27 | ||

Fifty-microliter portions of supernatants of MM1 cultures of P. agglomerans strains were tested by using the agar plate diffusion assay.

Carries the norM region of E. amylovora.

Parentheses indicate partial inhibition.

TABLE 5.

PCR and Southern blot screening for norM alleles in E. amylovora strains and related plant-associated species

| Strain | PCR | Southern bloting | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erwinia amylovora strains | |||

| GSPB 1189 | + | + | GSPBa |

| GSPB 1190, GSPB 1263, GSPB 1654, GSPB 1655, GSPB 1656, GSPB 1657, GSPB 1658, GSPB 1659, and GSPB 1839 | + | NDb | GSPB |

| Ea0, Ea1, Ea1/79, Ea8, Ea11, Ea266, PD576, PD579, and IL6 | + | ND | K. Geider |

| Erwinia pyrifoliae Ep1/96 | − | + | K. Geider |

| Erwinia rhapontici strains | |||

| DSM 4484 | − | + | F. Boernke |

| GSPB 454 | − | + | GSPB |

| Erwinia persicina strains | |||

| CFBP 3622 | − | + | K. Geider |

| GSPB 2443 | − | + | GSPB |

| Erwinia mallotivora CFBP 2503 | − | + | K. Geider |

| Erwinia psidii CFBP 3627 | − | + | K. Geider |

| Erwinia herbicola pv. gypsophilae 824-1 | − | + | I. Barash |

| Pantoea agglomerans Bel2/7 and QT2/5 | − | + | This study |

| Pantoea stewartii SW2 and SS104 | − | + | D. L. Coplin |

| Pectobacterium chrysanthemi AC 4150 and 3937 | − | + | A. Collmer |

| Pectobacterium carotovorum pv. carotovora 90 | − | + | B. Völksch |

| Brenneria quercina CFBP 3617 | − | + | K. Geider |

| Brenneria salicis CFBP 802 | − | + | K. Geider |

GSPB, Göttinger Sammlung phytopathogener Bakterien, Göttingen, Germany.

ND, not determined.

Fluorometric GUS assay.

E. amylovora mutant Ea225 contains the promoterless, β-glucuronidase (GUS)-encoding uidA gene on a mini-Tn5 transposable element (56) within the norM gene. This mutant was used to measure norM promoter activity in cis. Bacteria were cultivated in AMM2 supplemented with spectinomycin (25 μg/ml). To determine alterations of promoter activity in batch culture at 18 and 28°C, cells were harvested at different growth stages. The promoter activity was quantified by fluorometric analysis of GUS activity as described by Xiao et al. (62) by using a Fluorolite-100 microplate reader (Dynatech, Denkendorf, Germany) and 96-well microtiter plates.

Standard genetic procedures.

Restriction digestion, agarose gel electrophoresis, purification of DNA fragments from agarose gels, electroporation, PCR, and small-scale plasmid DNA preparation were performed by standard techniques (44). Cloning was done in pBBR1MCS, pBBR1MCS-2 (26, 27), and pBluescript II SK(+) (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany). Large-scale preparation of plasmid DNA from E. coli was performed by alkaline lysis, and the DNA was purified with Qiagen tip 100 columns (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Southern blot hybridizations were carried out with a digoxigenin DNA labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) by following the manufacturer's recommendations. The oligonucleotide primers specific for PCR amplification of norM in E. amylovora were 5′-GGCAGCAGCAGGTTTGTC (norM_Ea_fwd) and 5′-GTACGCCAGGCCTACTGG (norM_Ea_rev).

Comparative 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis.

PCR-mediated amplification of the 16S rRNA gene from nucleotide positions 28 to 1491 (nucleotide numbering according to the International Union of Biochemistry nomenclature for E. coli 16S rRNA) was carried out as described by Heyer et al. (19). The 16S ribosomal DNA PCR products were purified with a MiniElute PCR purification kit (Qiagen), and about 75 ng of PCR product was used for the nucleotide sequencing reaction with an ABI Big Dye Terminator kit (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany). Excess primers and dye terminators were removed with Autoseq G-50 columns (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany), and sequencing was performed with an ABI 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer) used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The closest phylogenetic neighbors were identified with a BLAST search (1).

Cloning and sequencing of the norM region of E. amylovora.

Cloning of the norM region of E. amylovora Ea1189 was performed by functional complementation of hypersensitive E. coli strain KAM3 as described below. Genomic DNA was isolated from Ea1189 based on the established method of Wilson (55) and was subsequently digested with restriction enzyme PstI. By using a shotgun cloning approach, DNA fragments of various sizes were ligated into vector pBBR1MCS. Competent KAM3 cells were transformed with the ligation products and spread on LB agar plates supplemented with chloramphenicol and norfloxacin (0.05 μg/ml). The latter antibiotic was used for selection of the norM region based on the results of Morita et al. (33) which indicated that norfloxacin is a substrate of the NorM efflux pump in E. coli. This led to isolation of pBBR.nor6, which potentially carried putative drug transporter open reading frames for norfloxacin resistance. To determine the nucleotide sequence of the complete 4.4-kb DNA insert, pBBR.nor6 was digested with BamHI, FspI, and BstXI. DNA fragments of the appropriate size were ligated into pBluescript II SK(+). Recombinant plasmids were used as templates for subsequent nucleotide sequencing, which was performed commercially (MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany). The single-strand nucleotide sequence data obtained were aligned and processed with the Lasergene sequence analysis software (version 5.0; DNASTAR Inc., Madison, Wis.) and Vector NTI Suite 8 (InforMax Inc., North Bethesda, Md.). DNA and protein sequence similarity searches of the EMBL, GenBank, PDBSTR, PIR, PRF, and SwissProt databases were performed with programs based on the BLAST algorithm (1) provided by the Bioinformatics Center of the Institute for Chemical Research, Kyoto University. Prediction of topology and localization of α-helices in transmembrane proteins were performed with the program TMHMM, which was provided by the Center for Biological Sequence Analysis at the Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark.

Generation of norM-deficient mutants of E. amylovora by marker exchange mutagenesis.

pCAM-MCS, a suicide vector for the Enterobacteriaceae, was used for generation of a gene disruption mutant of E. amylovora Ea1189. The vector was created by deleting mini-Tn5 and the transposase gene of pCAM140 (56) by SalI-EcoRI digestion and insertion of a SacI-KpnI fragment containing the multiple-cloning site of pBluescript II SK(+) by blunt end ligation. E. coli S17-1 λ-pir was used as the delivery host for pCAM-MCS derivatives.

A norM-deficient mutant of E. amylovora was generated by marker exchange mutagenesis as described below. A 3.2-kb ClaI-PstI fragment containing norM was subcloned from pBBR.nor6 into pBluescript II SK(+) to create pBlue.norM. The norM gene was mutagenized by insertion of a 2.1-kb chloramphenicol resistance cassette that was derived from plasmid pfd4 (13) into the unique EcoRV restriction site. The resulting plasmid, pBlue.norM-Cm, was digested with ClaI-SpeI, and the 5.3-kb fragment was subcloned into pCAM-MCS to generate pCAM.norM-Cm. This plasmid was transformed into electrocompetent E. amylovora cells by the standard protocol (44). Following electroporation, the bacteria were grown at 28°C for 1 h in SOC broth and plated on AMM2 containing chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml). To exclude mutants that resulted from single-crossover events, chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were transferred in parallel onto LB agar plates supplemented with chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml) and onto AMM2 agar plates supplemented with ampicillin (800 μg/ml). Chloramphenicol-resistant and ampicillin-sensitive colonies were selected and verified by PCR and Southern blot analyses.

Drug susceptibility test.

The MICs of drugs for E. coli and E. amylovora strains were determined by a broth microdilution assay performed in Mueller-Hinton broth (Becton-Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) and AMM2 broth, respectively. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of an antibiotic that completely stopped visible cell growth. All tests were done in triplicate by following the recommendations of the National Center for Clinical Laboratory Standards (35). Briefly, the MIC was determined in microtiter plates with 96 flat-bottom wells. With the exception of the wells used as controls, each well received 100 μl of a twofold dilution of an antibiotic solution in the appropriate medium. Next, each well except the wells used as sterility controls received 100 μl of a bacterial suspension (106 CFU of E. coli/ml of Mueller-Hinton broth; 2 × 106 CFU of E. amylovora per ml of AMM2 broth). Growth of E. coli and E. amylovora was examined by visual inspection after 24 h of incubation. Plates containing E. coli were incubated at 37°C. The tests with the E. amylovora strains were carried out at 18 and 28°C due to the observed temperature-dependent gene expression of norM.

Pathogenicity assay with apple plants.

Apple plants (Malus rootstock MM 106) were grown in a greenhouse at 20 to 25°C with 60% humidity and 12-h photoperiod (15,000 lx). E. amylovora norM mutant Ea1189-34 and the parent strain Ea1189, grown on LB agar plates for 48 h, were resuspended and diluted in sterile demineralized water for inoculation. Apple plants were inoculated by the prick technique described by May et al. (31). Five microliters of a bacterial suspension (102 to 106 CFU/ml) was placed onto each wound on a shoot tip. The plants were monitored daily for symptom development. Survival of bacteria in the plant tissue was determined by reisolation 1 day after inoculation. The bacterial populations were determined by cutting 1 cm of the shoot tip around the area of inoculated tissue. The shoot samples (n = 15) for each bacterial strain were pooled, homogenized in isotonic NaCl, and serially diluted, and appropriate dilutions were spread on LB agar plates. All greenhouse experiments were repeated at least three times to confirm the reproducibility and to calculate standard deviations.

Isolation of epiphytic microbes.

Apple, quince, and whitethorn blossom samples were obtained from different regions of Germany (Marburg, Eisemroth, Bauerbach, Vacha) during full bloom. Fifteen blossoms were collected from each tree and macerated in 15 ml of isotonic NaCl in a mortar. The suspension was subsequently diluted and plated on LB medium. After 48 h of incubation at 28°C, 25 to 30 typical colonies per sample were examined for growth inhibition of E. amylovora norM mutant Ea1189-34 and the parent strain by the agar plate diffusion assay. To do this, the E. amylovora strains were initially incubated for 20 h in AMM2 and diluted to obtain a concentration of 109 CFU/ml in isotonic NaCl. For preparation of the test plates (diameter, 150 mm), 50 ml of AMM2 agar was warmed to 48°C and supplemented with 500 μl of the diluted cell suspension. Blossom isolates were transferred in parallel onto the test plates supplemented with Ea1189-34 and the wild type. Zones of growth inhibition caused by the isolates were determined by visual inspection after 48 h of incubation at 28°C.

Agar plate diffusion assay.

Quantitative evaluation of antibiotic production by the P. agglomerans strains isolated from blossoms was accomplished by an agar plate diffusion assay. AMM2 agar plates with the E. amylovora norM mutant Ea1189-34 and the parent strain as test organisms were preapred as described above. The supernatants of liquid cultures of the P. agglomerans strains were used as test solutions. Wells (diameter, 10 mm) were punched in each agar plate with a cork borer, and 50 μl of test solution was pipetted into each well. On each plate, 50 μl of spectinomycin (5 mg/ml) was used as a positive control. After 24 h of incubation at 28°C and after 48 h of incubation at 18°C, the test plates were monitored for zones of growth inhibition on the bacterial lawns. For antibiotic production, the strains were incubated in MM1, which contained (per liter of demineralized water) 2 g of d-glucose, 4 g of (NH4)2SO4, 1 g of KH2PO4, 1 g of K2HPO4, 1 g of NaCl, 1 g of sodium citrate, and 0.7 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the norM gene of E. amylovora reported in this study has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AY307101.

RESULTS

Identification of a norM homologue in E. amylovora.

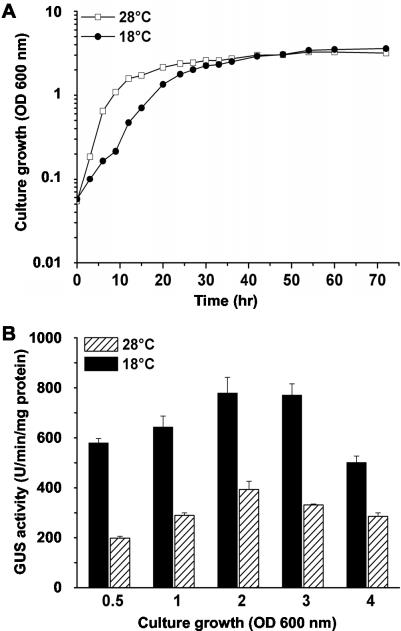

Fire blight is distributed in the temperate climate zones where temperatures of 15 to 20°C are accompanied by high relative humidity, which favors infection of a host plant by E. amylovora (3, 8, 9, 48). During screening for temperature-dependent gene expression in this pathogen, a gene was identified which presumably encodes a multidrug efflux transporter (14). The effect of temperature on the promoter activity of this gene was examined by analyzing the GUS activity in E. amylovora mutant Ea225. This mutant harbors a promoterless uidA gene inserted in the putative transporter gene. GUS activity was monitored in batch cultures of Ea225 grown at 18 and 28°C. The activity at 18°C was about twofold greater than the activity at 28°C (Fig. 1). At both temperatures, the activity remained relatively constant throughout the exponential and stationary growth phases. A slight increase in activity during the onset of the stationary phase and a slight decrease at the end of the stationary phase were observed at both 18 and 28°C.

FIG. 1.

Temperature-dependent promoter activity of norM from E. amylovora as determined by using a transcriptional fusion with the reporter gene uidA. E. amylovora mutant Ea225 carrying uidA on a mini-Tn5 transposable element inserted into the genome was used to determine expression of GUS during growth in liquid AMM2. (A) Growth kinetics of Ea255 (norM′-uidA+); (B) GUS activity of Ea225 (norM′-uidA+). OD 600 nm, optical density at 600 nm.

Cloning of norM from E. amylovora and nucleotide sequence analysis.

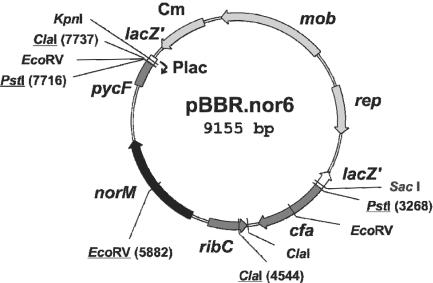

Plasmid pBBR.nor6 was obtained by restriction digestion of Ea1189 genomic DNA, ligation into pBBR1MCS, and transformation of the ligation products into E. coli KAM3 with selection on chloramphenicol and norfloxacin (Fig. 2). The sequence of the 4.4-kb PstI insert was determined, and the results revealed the presence of a complete open reading frame encoding a 457-amino-acid protein with a predicted molecular mass of 49.2 kDa. The deduced amino acid sequence was compared with protein database entries by using the BLASTP program (1). It exhibited significant similarity to transporters belonging to the MATE family (5), including NorM of E. coli (73% identity) (33), NorM of Vibrio parahaemolyticus (55% identity) (33), and VcmA of Vibrio cholerae (50% identity) (20). Based on these results, the gene identified in E. amylovora was designated norM. It is flanked upstream by a gene coding for riboflavin synthetase and downstream by gene encoding a pyruvate kinase.

FIG. 2.

Restriction map of plasmid pBBR.nor6 carrying the norM locus of E. amylovora. Restriction sites used for subcloning are underlined. Cm, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase; mob, gene region required for plasmid mobilization; rep, gene region required for plasmid replication; lacZ′, gene encoding the first 146 amino acids of β-galactosidase.

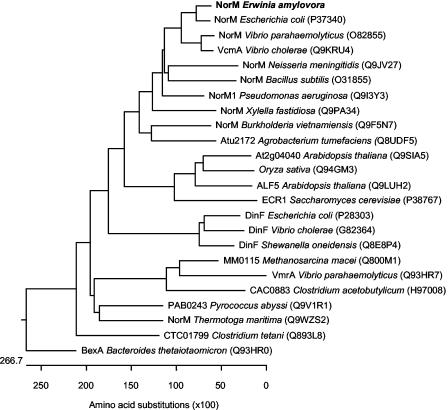

Members of the MATE family are uniquely distributed among plants and microbes. Hydropathy analysis of the deduced norM amino acid sequence with the computer program TMHMM revealed the typical topology of the MATE type of bacterial membrane proteins (i.e., 12 hydrophobic domains, presumably corresponding to the corresponding transmembrane segments) (data not shown). Brown et al. (5) divided the MATE family into three clusters on the basis of phylogenetic studies. The first and second clusters are found in prokaryotes, whereas the third cluster is composed exclusively of eukaryotic proteins from either fungi or plants. Based on sequence relatedness, we suggest that NorM of E. amylovora can be classified in the first group, which includes the multidrug efflux transporters of E. coli, V. parahaemolyticus, V. cholerae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Neisseria meningitidis and several functionally uncharacterized homologues from different bacteria (Fig. 3). These transporters are known to provide protection against structurally unrelated drugs. However, hydrophobic cationic compounds appear to be preferred substrates of these multidrug efflux proteins (20, 33, 42).

FIG. 3.

Rooted phylogenetic tree for NorM and its homologues. The dendrogram was generated with MegAlign, version 5.0 (DNASTAR Inc.), by using the ClustalW method. NorM of E. amylovora belongs to a cluster containing multidrug efflux transporters from members of the Eubacteria.

Heterologous expression of norM in E. coli KAM3.

The substrate specificity of NorM from E. amylovora was studied by examining heterologous expression of the corresponding gene in E. coli strain KAM3, which is hypersensitive to many drugs due to a deficiency of the major multidrug efflux pump AcrAB (33). The drug susceptibilities of KAM3(pBBR.norM) harboring norM from E. amylovora and of KAM3(pBBR1MCS) are shown in Table 3. Plasmid pBBR.norM was generated by subcloning a 3.2-kb ClaI fragment from pBBR.nor6 into pBBR1MCS in order to truncate ribC, which is located upstream of norM. Subsequently, a wide variety of toxic compounds were tested. Compared to the control, KAM3(pBBR.norM) exhibited elevated resistance to norfloxacin (fivefold), crystal violet (fourfold), ethidium bromide (fourfold), and berberine (fourfold). Moreover, NorM from E. amylovora conferred twofold-greater resistance to ciprofloxacin, methylene blue, ampicillin, and kanamycin. The antibiotics nalidixic acid, spectinomycin, carbenicillin, and tetracycline were not substrates for this transporter (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Susceptibilities of E. coli strains to different antimicrobial agentsa

| Compound | MIC (μg/ml) for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG1 | KAM3b | KAM3 (pBBR.norM)c | KAM3 (pBBRnorM.Ec)d | |

| Norfloxacin | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.02 | 0.006 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Ampicillin | 3.1 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| Kanamycin | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Crystal violet | 12.5 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| Methylene blue | 500 | 3.1 | 6.3 | 6.3 |

| Ethidium bromide | 125 | 4 | 15.6 | 15.6 |

| Berberine | >1,000 | 62.5 | 250 | 125 |

| Phloretin | >1,000 | 62.5 | 125 | 125 |

The MIC was determined by the microdilution assay in Mueller-Hinton broth at least three times in each case, and the consistency of each MIC was confirmed.

There was no change in the MIC for strain KAM3 when the host was transformed with the vector pBBR1MCS alone.

Carries the norM region of E. amylovora.

Carries the norM region of E. coli.

Furthermore, NorM increased the resistance to the apple phytoalexin and isoflavonoid phloretin twofold compared to the resistance of KAM3(pBBR1MCS) (Table 3). Phytoalexins are defined as low-molecular-weight antimicrobial compounds involved in plant defense. For members of the Rosaceae no evidence of phytoalexin induction in response to E. amylovora infection has been obtained so far. However, constitutive levels of isoflavonoids, which often exhibit antimicrobial activity, are widely distributed in this plant family (15, 16). Other isoflavonoids known from apple (49), such as the flavonol quercetin, the flavanone naringenin, the monomeric flavanol (+)-catechin, the hydroxycinnamic acid derivative chlorogenic acid, and the benzoic acid derivative protocatechuic acid, did not appear to be substrates of NorM in E. amylovora (data not shown).

Because NorM from E. amylovora exhibited the highest level of similarity to NorM from E. coli, the substrate profiles of the two transporters were compared. The norM gene of E. coli was obtained from pMEC2 by HindII-XbaI digestion (33), and the 2.4-kb fragment was cloned into pBBR1MCS. The resulting plasmid, pBBR.norM.Ec, was included in the analyses. NorM from E. coli exhibits substrate specificity similar to that of NorM from E. amylovora (Table 3). However, the transporter from E. coli prevented accumulation of norfloxacin and ciprofloxacin in KAM3 more efficiently than NorM from E. amylovora did.

Our results indicated that NorM of E. amylovora provides protection, particularly against hydrophobic cationic compounds corresponding to substrate profiles reported for related MATE-type multidrug efflux transporters (20, 33, 42).

Generation of norM-deficient mutants.

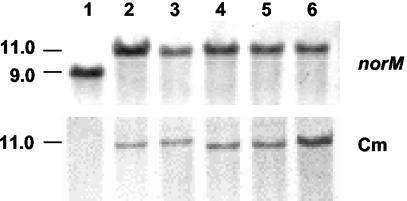

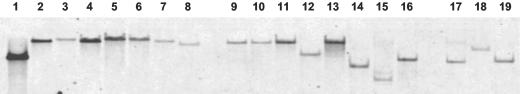

To study the physiological function of NorM from E. amylovora in the natural environment of the plant pathogen, norM-deficient mutants were generated by marker exchange mutagenesis by using the suicide plasmid pCAM.norM-Cm. PCR tests were performed to confirm integration of the chloramphenicol resistance cassette into the norM locus by homologous recombination. A 1.0-kb PCR product was detected for the wild-type gene when it was amplified with primers norM_Ea_fwd and norM_Ea_rev. PCR analysis with Aps Cmr transformants revealed a signal shifted to 3.1 kb, suggesting that the norM gene was inactivated by integration of the 2.1-kb chloramphenicol resistance cassette. The PCR results were verified by Southern blot analyses (Fig. 4). Genomic DNA of five transformants were digested with ClaI and hybridized with DNA probes containing norM, the chloramphenicol resistance cassette, and pCAM-MCS. The signal of the norM probe was shifted in samples derived from the transformants by the size of the inserted chloramphenicol resistance cassette. The chloramphenicol probe highlighted a single DNA fragment that was the same size, and the pCAM-MCS probe failed to hybridize, indicating that in the genomic DNA of the mutants the native alleles had been replaced by a double-crossover event.

FIG. 4.

Southern blot analysis of E. amylovora insertion mutants. ClaI-digested genomic DNA was hybridized with a 1.0-kb digoxigenin-labeled norM probe and a 2.1-kb digoxigenin-labeled probe containing the chloramphenicol resistance cassette. Lane 1, Ea1189 (wild type); lane 2, Ea1189-14; lane 3, Ea1189-22; lane 4, Ea1189-23; lane 5, Ea1189-29; lane 6, Ea1189-34. The hybridization patterns indicated that in the mutants the chloramphenicol resistance cassette was inserted into norM by double crossover.

Phenotypic analysis of the norM mutants was performed by comparing the susceptibilities of the mutants and the parent strain to the antibiotics and dyes used for determination of the MICs for the E. coli strains described above. Surprisingly, the norM mutants were as resistant as the wild type to all compounds previously examined in MIC assays. This result suggested that NorM performs different functions in E. coli and E. amylovora despite the fact that norM of E. amylovora could render E. coli KAM3 resistant to various drugs described above.

Contribution of the multidrug efflux transporter NorM to the virulence of E. amylovora.

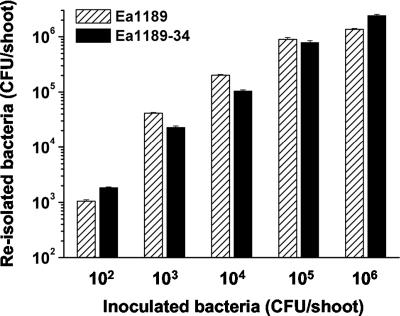

The impact of NorM on the virulence of the fire blight pathogen was evaluated by studying development of disease symptoms and by monitoring the establishment of a bacterial population 24 h after inoculation in apple rootstock MM 106. The shoot tips were inoculated by the prick technique (31), which mimics the natural infection process, in which pathogens often enter the plant through open wounds. An advantage of this method is that defined numbers of bacterial cells can be inoculated onto the pin-pricked wounds. Both E. amylovora mutant Ea1189-34 and the parent strain were inoculated simultaneously on one plant but on different shoots, which resulted in identical growth conditions.

To assess the development of fire blight symptoms, 15 apple shoots were inoculated with the mutant and 15 apple shoots were inoculated with the wild type. After 3 weeks of incubation, both the mutant and the wild type caused typical fire blight symptoms, such as ooze formation, necrosis, and the shepherd's crook-like bending of the shoot tip on 9 of 15 shoots. Furthermore, the mutant was capable of establishing a population density 24 h after inoculation comparable to that of the wild type (Fig. 5). The virulence of Ea1189-34 was not diminished on apple plants, and we assume that the NorM transporter is not involved in the interaction of the fire blight pathogen with this host.

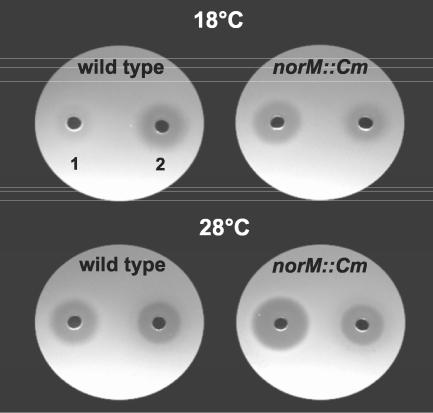

FIG. 5.

Growth inhibition of the E. amylovora wild type and mutant Ea1189-34 (norM::Cm) caused by the supernatant of P. agglomerans Bel2/7. The antimicrobial activity of strain Bel2/7 was determined by agar plate diffusion assays carried out at 18 and 28°C. Well 1, supernatant of MM1 culture of strain Bel2/7; well 2, spectinomycin (5 μg/ml).

This observation was substantiated by comparing the susceptibilities of Ea1189-34 and the parent strain to six different isoflavanoids which are known as phytoalexins from apple and which were used previously for determination of the MIC for E. coli strains. The norM mutant appeared to be as resistant as the wild type against all the compounds examined in MIC assays (data not shown).

Isolation of blossom-colonizing microbes.

During its infection cycle, E. amylovora is exposed not only to toxic compounds involved in plant defense but also to antibiotics produced by microbes cocolonizing the plant surface. The fire blight pathogen has to circumvent the toxic effects of these compounds. Therefore, the role of the multidrug efflux protein NorM from E. amylovora was investigated in terms of interactions with other microbes isolated from blossoms of host plants.

Epiphytic bacteria were isolated from blossom samples which were obtained in the middle of the full bloom period of 14 apple trees, two quince trees, and two whitethorn shrubs in different regions of Germany. The production of antimicrobial compounds by more than 500 isolates was examined on agar plates by using Ea1189-34 and the parent strain as test organisms. Bacteria isolated from the blossoms of four apple trees and one quince tree significantly inhibited the growth of the norM mutant but not the growth of the wild type. Isolates which inhibited both the growth of the mutant and the growth of the wild type were obtained from blossoms of only one apple tree.

All bacterial isolates that caused differential growth inhibition of Ea1189-34 formed yellow-pigmented, mucoid colonies whose shapes were similar. Therefore, we speculated that these isolates might belong to one species. To corroborate this hypothesis, one isolate from each tree was selected for genomic DNA purification and subsequent PCR-mediated amplification of the 16S rRNA gene. Comparison of the nucleic acid sequences of the PCR products with database entries by using the BLASTX program (1) clearly indicated that the five strains analyzed were affiliated with the species P. agglomerans (data not shown).

Susceptibility to antibiotics from P. agglomerans.

The P. agglomerans strains isolated from blossoms were cultivated in liquid MM1 to screen for the production of antibiotics. The activities of the antibiotics in the supernatants were examined by performing agar plate diffusion assays with Ea1189-34 and its parent strain as test organisms. The assays were carried out at 18 and 28°C because transcription of norM was shown to be induced at the lower temperature.

At 18°C the supernatants of all P. agglomerans strains tested inhibited growth of the norM mutant but did not interfere with growth of the wild type (Table 4). At 28°C the wild type was also inhibited; however, only partial inhibition zones were observed (Fig. 6). These results indicated that growth of the norM mutant was inhibited more efficiently at 28°C than at 18°C. Interestingly, these results are in line with the results described above for the temperature-dependent expression pattern of norM.

FIG. 6.

Virulence assay with apple rootstock MM 106. The E. amylovora wild type and mutant Ea1189-34 (norM::Cm) were inoculated by the prick technique in shoot tips. The establishment of a population was determined by reisolating the bacteria 24 h after inoculation.

Furthermore, complementation of Ea1189-34 with pBBR2.norM harboring norM completely restored resistance to the P. agglomerans antibiotics (Table 4). The plasmid was generated by subcloning a 3.2-kb ClaI-PstI fragment containing norM from pBBR.nor6 into pBBR1MCS-2 to create pBBR2.norM. In contrast to the inhibition of the wild type at 28°C, the growth of the complemented mutant was not affected at this temperature, suggesting that there was a plasmid copy number effect. Interestingly, norM from E. coli which was subsequently also expressed in Ea1189-34 also conferred resistance to the antimicrobial metabolites from P. agglomerans at both temperatures (data not shown).

Most of the antibiotics synthesized by P. agglomerans are known to interfere with amino acid biosynthetic pathways (12, 60). Consequently, we tested whether the inhibition of Ea1189-34 growth by P. agglomerans isolates could be abolished in the presence of l-histidine. This was indeed the case (data not shown), demonstrating that the antimicrobial compounds from P. agglomerans might interfere with amino acid biosynthetic pathways in E. amylovora. In summary, NorM of E. amylovora appears to play an important role in the interaction of the pathogen with epiphytic bacteria and thus in the epiphytic fitness of the pathogen.

Distribution of norM among E. amylovora strains and related plant-associated bacteria.

Multidrug efflux proteins are ubiquitously distributed among prokaryotes. E. amylovora belongs to the Enterobacteriaceae. Previously, norM-like genes were identified in human-pathogenic members of this family (i.e., in the genera Enterobacter, Escherichia, Klebsiella, Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia) (40). To determine if norM is also present in different plant-pathogenic enterobacteria, PCR and Southern blot analyses were carried out. The norM-specific primers norM_Ea_fwd and norM_Ea_rev were used to amplify a PCR product from genomic DNA of 19 E. amylovora strains. All strains tested provided a 1.0-kb signal regardless of their geographic origin (Table 5). PCR with samples of representative strains from related plant-associated species did not result in any detectable amplification, possibly due to the specificity of the PCR method. In contrast, Southern blot analysis at low stringency (50°C) revealed the occurrence of norM homologues in strains of all six Erwinia species tested (Table 5 and Fig. 7). Furthermore, the norM probe hybridized with genomic DNA from nine strains belonging to the genera Pantoea, Pectobacterium, and Brenneria, which are phylogenetically related to Erwinia (18). These results suggest that the NorM transport protein is widely distributed in human- and plant-pathogenic enterobacteria.

FIG. 7.

Distribution of norM-like genes among plant-associated enterobacteria. Southern blot analysis was performed by using total chromosomal DNA digested with ClaI and probed with a digoxigenin-labeled 1.0-kb PCR product of the norM gene from E. amylovora. Hybridization was carried out at 50°C. Lane 1, E. amylovora GSPB 1189; lane 2, Erwinia pyrifoliae Ep1/96; lane 3, Erwinia rhapontici GSPB 454; lane 4, Erwinia rhapontici DSM 4484; lane 5, Erwinia persicina CFBP 3622; lane 6, Erwinia persicina GSPB 2443; lane 7, Erwinia mallotivora CFBP 2503; lane 8, Erwinia psidii CFBP 3627; lane 9, Erwinia herbicola pv. gypsophilae 824-1; lane 10, P. agglomerans 2b/89; lane 11, P. agglomerans 52c/90; lane 12, Pantoea stewartii SW2; lane 13, Pantoea stewartii SS104; lane 14, Pectobacterium chrysanthemi AC4150; lane 15, Pectobacterium chrysanthemi 3937; lane 16, Pectobacterium carotovorum pv. carotovora 90; lane 17, Brenneria quercina CFBP 3617; lane 18, Brenneria salicis CFBP 802; lane 19, E. coli TG1.

DISCUSSION

To successfully infect a host plant, the fire blight pathogen E. amylovora has to circumvent an extensive arsenal of plant defense mechanisms. In a recent study, we identified a multidrug efflux system, AcrAB, which mediates resistance against some phytoalexins, such as phloretin, in E. amylovora cells (6). However, E. amylovora also has to compete for space and nutrient resources with other microorganisms during the epiphytic stage in its infection cycle. On plant surfaces, indigenous microbial communities are capable of altering the outcome of plant-pathogen interactions before infection occurs and thus protect a plant from disease. On the one hand, fitness and survival of microorganisms in this habitat can be favored by the production of antibiotics that inhibit the growth of competing microbes. On the other hand, the ability to resist such toxic effects obviously is a prerequisite to survive in the habitat. The major novel finding described in this report is that plant-pathogenic bacteria can use a multidrug efflux system(s) to resist antibiotics synthesized by epiphytes.

In the fire blight pathogen E. amylovora, a putative multidrug efflux protein was identified in the course of screening for temperature-dependent gene expression (14). Based on reporter gene analysis, the promoter of the corresponding gene exhibited twofold-greater activity at 18°C than at 28°C. So far, temperature-regulated transcription of a gene encoding a multidrug efflux protein has been described only in human-pathogenic bacteria. In Yersinia species, for example, Bengoechea and Skurnik (2) reported increased expression of the rosAB locus at 37°C. The RosA/RosB transport system protects bacteria against cationic antimicrobial peptides. In this case, the inducing temperature is associated with the nature of the warm-blooded host (i.e., humans or animals). For E. amylovora, low temperatures might represent typical environmental conditions during epiphytic growth in blossoms and during the infection process. Whether compounds synthesized by epiphytic antagonists of E. amylovora investigated in this study are produced preferably at low temperatures will be investigated in detail once the nature of such compounds has been investigated in more detail.

Sequence analysis revealed that the temperature-regulated gene in E. amylovora codes for a protein with significant similarity to multidrug efflux transporters belonging to the MATE family. NorM of E. amylovora is the first member of this family characterized from a phytopathogenic bacterium. The norM gene was found to be flanked by genes encoding a riboflavin synthetase and a pyruvate kinase. It can be assumed that norM is monocistronically transcribed and promotes efflux as a single-component transporter into the periplasmic space. In contrast, multicomponent efflux pumps allow, in concert with a periplasmic linker protein and an outer membrane channel, extrusion of substrates directly into the external medium, bypassing the periplasm and the outer membrane (63). The MATE-type transporters NorM of E. coli and VcmA of V. parahaemolyticus, as well as VmrA of V. cholerae, mediate transport via Na+-drug antiport (7, 20, 34). In E. amylovora, the driving force of the drug efflux remains to be elucidated.

We identified hydrophobic cationic compounds as substrates for NorM of E. amylovora, which corresponds to the substrate profiles reported for homologous transporters of E. coli, V. parahaemolyticus (7, 33), V. colerae (20), N. gonorrhoeae, and N. meningitidis (42). Rouquette-Loughlin et al. (42) reported that the cationic moiety of the substrates is important for drug recognition by the NorM-like proteins in N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis.

Surprisingly, the E. amylovora mutant lacking norM was not susceptible to compounds for which the acrAB mutant KAM3 of E. coli overexpressing norM showed resistance. However, this phenomenon has been observed previously (45) and may be attributed to several potential scenarios. One possible explanation is that the effect of the deletion could have been masked by other transporters which have overlapping substrate profiles. In fact, in E. coli, the contribution of the transporters EmrAB (46) and NorM (7) to multidrug resistance could not be determined until a deletion in acrAB was generated. Moreover, a report by Lee et al. (28) indicated that simultaneous expression of a single-component transporter and a multicomponent transporter resulted in much greater resistance to drugs than the resistance mediated by each of the transporters expressed separately. This may also be true for NorM since a homologue of the multicomponent pump from E. coli, AcrAB, was identified in E. amylovora (6). Interestingly, the AcrAB homologue in E. amylovora has a substrate spectrum which includes substances also transported by NorM.

Based on the fact that efflux pumps are often poorly expressed, another explanation might be that a required inducer is not present under the assay conditions used. Such inducers have been identified frequently in the natural habitat of an microorganism. For example, the environment of enteric bacteria is enriched in bile salts and fatty acids. The acrAB operon of E. coli is induced by the fatty acid decanonate (30), and the mtrCDE operon of N. gonorrhoeae is induced by the detergent Triton X-100, which resembles hydrophobic agents that naturally occur in the intestine (41). In an Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain colonizing alfalfa roots, different isoflavonoids exuded from the legume roots increased expression of the ifeAB operon (37). A third possible scenario is that the E. amylovora NorM protein folds differently in E. coli than in its host organism, thereby altering its substrate recognition site(s). Neither of these possible scenarios can be excluded at this time and will be tested in future studies.

In members of the plant family Rosaceae a wide variety of constitutively occurring isoflavonoids, which frequently act as phytoalexins in plant defense, have been identified (15, 16, 25). However, in contrast to our findings for the AcrAB system of E. amylovora (6), it appeared that NorM is not involved in resistance of E. amylovora to apple isoflavonoids (32, 49). Virulence assays with the apple rootstock MM 106 revealed that the norM mutant caused symptoms and established population densities in the plant tissue comparable to those observed with the wild type, suggesting that NorM does not contribute to the virulence of E. amylovora.

Here, we clearly demonstrated that NorM of E. amylovora provides protection against antibiotics produced by epiphytic P. agglomerans strains. Thus, the multidrug efflux transporter may be important for epiphytic fitness of the plant pathogen. It is widely accepted that E. amylovora survives poorly on plant surfaces except for the stigmatic areas of pistils (47, 57). The occurrence of high population densities of the fire blight pathogen seems to be required for efficient dissemination from flower to flower by rain or insects, and more importantly, it favors the successful infection of the host plant. In different regions of Germany, blossoms were collected from potential plant hosts of E. amylovora. The epiphytic microbes isolated were examined for the ability to produce antibiotics directed against E. amylovora. One-third of all blossoms examined were colonized by epiphytes which inhibited the growth of the norM mutant compared to the growth of the wild type. Thus, NorM appears to be an important mechanism of resistance against frequently occurring antibiotic-producing epiphytes. On the basis of 16S rRNA analyses, the growth-inhibiting isolates were identified as P. agglomerans. This bacterial species has been investigated widely for its ability to suppress floral infection by E. amylovora and for its use as a commercially available biological control agent (22, 23, 24, 36, 53). Our findings might be important for use of P. agglomerans in biological control since the fire blight pathogen obviously employs resistance mechanisms to combat antibiotics from this epiphyte.

The growth-inhibitory effects were assayed at 18 and 28°C, because the expression of norM appeared to be induced twofold at the lower temperature. At 18°C, the growth of the norM mutant was significantly inhibited, whereas the growth of the wild type was not affected. At 28°C, the growth of the wild type was also inhibited, but the inhibition was clearly weaker than the obvious growth inhibition of the mutant. The intrinsic resistance of the E. amylovora wild type to P. agglomerans antibiotics at 18°C may be attributed to increased norM expression at this temperature. It is tempting to speculate that low temperatures may be important for the infectivity of E. amylovora because they might increase the availability of moisture necessary for movement of the bacteria from the stigmas to natural openings in the floral cup. Thus, the plant pathogen needs to compete successfully with other microbes for space and nutrient resources to reach a high population density at this temperature. Since P. agglomerans and E. amylovora strains colonize similar habitats on the stigmatic surface (17), the pathogen might recruit multidrug efflux mechanisms for resistance to antibiotics produced by P. agglomerans epiphytes.

Recently, Llama-Palacios et al. (29) reported that the lack of the putative ABC transporter YbiT in the soft-rot pathogen Pantoea chrysanthemi resulted in a reduced ability of P. chrysanthemi to compete in planta against a saprophytic Pseudomonas putida strain. YbiT exhibits sequence similarity to a transporter in Streptomyces spp. that confers resistance to macrolide antibiotics. However, the substrate of YbiT has not been identified. The substance class(es) of the antibiotics produced by P. agglomerans which inhibit the growth of the E. amylovora norM mutant remains to be elucidated. Generally, antibiotics of P. agglomerans can be divided into different groups based on the amino acids that reverse the activity of these toxins (12, 60). The growth inhibition of the E. amylovora norM mutant by all P. agglomerans strains tested could be abolished by addition of l-histidine. Although most strains of P. agglomerans produce l-histidine-reversible antibiotics (12, 60), only a few of the antibiotics were examined in detail, like MccEh252 produced by P. agglomerans strain Eh252 (53), pantocin A produced by strain Eh318 (61), and herbicolin O produced by strain C9-1 (21). None of these compounds has been structurally characterized so far. MccEh252 has been proposed to be a peptide due to its protease sensitivity (53). Wright et al. (61) assumed that pantocin A is also a peptide based on the physicochemical properties of this compound. Moreover, Southern blot analyses revealed homologous genes involved in antibiotic biosynthesis in P. agglomerans strains Eh252, Eh318, and C9-1, suggesting that all three antibiotics may fall into a family of structurally related compounds (61). Whether the antibiotic of P. agglomerans that is inhibitory to the norM mutant of E. amylovora is also a peptide will be the subject of further experiments in our laboratory. In these experiments we will try to identify the antagonistic principle(s) secreted by the P. agglomerans strain tested and relate this information to known peptide toxins formed by this epiphyte (53, 60, 61). In addition, in planta studies will be conducted to highlight the ecological importance of NorM. In these studies, P. agglomerans and E. amylovora wild-type and norM mutant cells will be inoculated into apple blossoms in different combinations, and survival rates will be determined under various environmental conditions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Max Planck Society.

We thank P. Dunfield for carrying out the comparative 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. We thank T. Tsuchiya and Y. Morita for providing E. coli strain KAM3. Furthermore, we are grateful to C. Goyer for providing E. amylovora mutant Ea225 and to I. Barash, F. Boernke, A. Collmer, D. L. Coplin, K. Geider, K. Rudolph, and B. Völksch for providing strains of E. amylovora and related plant-associated bacteria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bengoechea, J. A., and M. Skurnik. 2000. Temperature-regulated efflux pump/potassium antiporter system mediates resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides in Yersinia. Mol. Microbiol. 37:67-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billing, E. 1980. Fireblight (Erwinia amylovora) and weather: a comparison of warning systems. Ann. Appl. Biol. 95:365-377. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackmore, C. G., P. A. McNaughton, and H. W. van Veen. 2001. Multi-drug transporters in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells: physiological functions and transport mechanisms. Mol. Membr. Biol. 18:97-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, M. H., I. T. Paulsen, and R. A. Skurray. 1999. The multi-drug efflux protein NorM is a prototype of a new family of transporters. Mol. Microbiol. 31:394-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burse, A., H. Weingart, and M. S. Ullrich. 2004. The phytoalexine-inducible multi-drug efflux pump, AcrAB, contributes to virulence in the fire blight pathogen, Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 17:43-54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Chen, J., Y. Morita, M. N. Huda, T. Kuroda, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 2002. VmrA, a member of a novel class of Na+-coupled multidrug efflux pumps from Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Bacteriol. 184:572-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colhoun, J. 1973. Effects of environmental factors on plant disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 11:343-364. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deckers, T. 1996. Fire blight control under temperate zone climatology. Acta Hortic. (The Hague) 411:417-426. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eastgate, J. A. 2000. Erwinia amylovora: the molecular basis of fire blight disease. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 1:325-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eden-Green, S. J., and E. Billing. 1974. Fireblight. Rev. Plant Pathol. 46:594-599. [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Gorani, M. A., F. M. Hassanein, and A. A. Shoeib. 1992. Antibacterial and antifungal spectra of antibiotics produced by different strains of Erwinia herbicola (= Pantoea agglomerans). J. Phytopathol. 136:335-339. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geider, K., C. Hohmeyer, R. Haas, and T. F. Meyer. 1985. A plasmid cloning system utilizing replication and packaging functions of filamentous bacteriophage fd. Gene 33:341-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goyer, C., and M. S. Ullrich. 1999. Thermoregulation of virulence gene expression in the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora. Acta Hortic. (The Hague) 489:321-326. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grayer, R. J., and T. Kokubun. 2001. Plant-fungal interactions: the search for phytoalexins and other antifungal compounds from higher plants. Phytochemistry 56:253-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harborne, J. B. 1999. The comparative biochemistry of phytoalexin induction in plants. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 27:335-367. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hattingh, M. J., S. V. Beer, and E. W. Lawson. 1986. Scanning electron microscopy of apple blossoms colonized by Erwinia amylovora and E. herbicola. Phytopathology 76:900-904. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hauben, L., E. R. B. Moore, L. Vauterin, M. Steenackers, J. Mergaert, L. Verdonck, and J. Swings. 1998. Phylogenetic position of phytopathogens within the Enterobacteriaceae. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21:384-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heyer, J., V. F. Galchenko, and P. F. Dunfield. 2002. Molecular phylogeny of type II methane-oxidizing bacteria isolated from various environments. Microbiology 148:2831-2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huda, M. N., Y. Morita, T. Kurodo, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 2001. Na+-driven multi-drug efflux pump VcmA from Vibrio cholerae non-01, a non-halophilic bacterium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 203:235-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishimaru, C. A., E. J. Klos, and R. R. Brubaker. 1988. Multiple antibiotic production by Erwinia herbicola. Phytopathology 78:746-750. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson, K. B., and V. O. Stockwell. 2000. Biological control of fire blight, p. 319-337. In J. L. Vanneste (ed.), Fire blight: the disease and its causative agent, Erwinia amylovora. CABI Publishing, Oxon, United Kingdom.

- 23.Johnson, K. B., V. O. Stockwell, R. J. McLaughlin, D. Sugar, J. E. Loper, and R. G. Roberts. 1993. Effect of bacterial antagonists on establishment of honey bee-dispersed Erwinia amylovora in pear blossoms and on fire blight control. Phytopathology 83:995-1002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerns, L. P., and C. N. Hale. 1993. Biological control of fire blight by Erwinia herbicola: survival of applied bacteria in orchard and glasshouse trials. Acta Hortic. (The Hague) 338:333-337. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kokubun, T., and J. B. Harborne. 1995. Phytoalexin induction in the sapwood of plants of the Maloideae (Rosaceae): biphenyls or dibenzofurans. Phytochemistry 40:1649-1654. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kovach, M. E., P. H. Elzer, D. S. Hill, G. T. Robertson, M. A. Farris, R. M. Roop 2nd, and K. M. Peterson. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovach, M. E., R. W. Phillips, P. H. Elzer, R. M. Roop 2nd, and K. M. Peterson. 1994. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host-range cloning vector. BioTechniques 16:800-802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, A., W. Mao, M. S. Warren, A. Mistry, K. Hoshino, R. Okumura, H. Ishida, and O. Lomovskaya. 2000. Interplay between efflux pumps may provide either additive or multiplicative effects on drug resistance. J. Bacteriol. 182:3142-3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Llama-Palacios, A., E. Lopez-Solanilla, and P. Rodriguez-Palenzuela. 2002. The ybiT gene of Erwinia chrysanthemi codes for a putative ABC transporter and is involved in competitiveness against endophytic bacteria during infection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1624-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma, D., D. N. Cook, M. Alberti, N. G. Pon, H. Nikaido, and J. E. Hearst. 1995. Genes acrA and acrB encode a stress-induced efflux system in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 16:45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.May, R., B. Völksch, and G. Kampmann. 1997. Antagonistic activities of epiphytic bacteria from soybean leaves against Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea in vitro and in planta. Microb. Ecol. 34:118-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayr, U., D. Treutter, C. Santos-Buelga, H. Bauer, and W. Feucht. 1995. Developmental changes in the phenol concentrations of Golden Delicious apple fruits and leaves. Phytochemistry 38:1151-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morita, Y., A. Kataoka, S. Shiota, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 2000. NorM of Vibrio parahaemolyticusis, a Na+-driven multidrug efflux pump. J. Bacteriol. 182:6694-6697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morita, Y., K. Kodama, S. Shiota, T. Mine, A. Kataoka, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 1998. NorM, a putative multidrug efflux protein, of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and its homolog in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1778-1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards.2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard,thed. NCCLS document M07-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 36.Nuclo, R. L., K. B. Johnson, V. O. Stockwell, and D. Sugar. 1998. Secondary colonization of pear blossoms by two bacterial antagonists of the fire blight pathogen. Plant Dis. 82:661-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palumbo, J. D., C. I. Kado, and D. A. Phillips. 1998. An isoflavonoid-inducible efflux pump in Agrobacterium tumefaciens is involved in competitive colonization of roots. J. Bacteriol. 180:3107-3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pao, S. S., I. T. Paulsen, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1998. Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paulsen, I. T., M. H. Brown, and R. A. Scurray. 1996. Proton-dependent multidrug efflux systems. Microbiol. Rev. 60:575-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paulsen, I. T., J. Cen, K. E. Nelson, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 2001. Comparative genomics of microbial drug efflux systems. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 3:145-150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rouquette, C., J. B. Harmon, and W. M. Shafer. 1999. Induction of the mtrCDE-encoded efflux pump system of Neisseria gonorrhoeae requires MtrA, an AraC-like protein. Mol. Microbiol. 33:651-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rouquette-Loughlin, C., S. A. Dunham, M. Kuhn, J. T. Balthazar, and W. M. Shafer. 2003. The NorM efflux pump of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis recognizes antimicrobial cationic compounds. J. Bacteriol. 185:1101-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saier, M. H., Jr., J. T Beatty, A. Goffeau, K. T. Harley, W. H. Heijne, S. C. Huang, D. L. Jack, P. S. Jahn, K. Lew, J. Liu, S. S. Pao, I. T. Paulsen, T. T. Tseng, and P. S. Virk. 1999. The major facilitator superfamily. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1:257-279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russel.2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 45.Sulavik, M. C., C. Houseweart, C. Cramer, N. Jiwani, N. Murgolo, J. Greene, B. DiDomenico, K. J. Shaw, G. H. Miller, R. Hare, G. and Shimer. 2001. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Escherichia coli strains lacking multidrug efflux pump genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1126-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thanassi, D. G., L. W. Cheng, and H. Nikaido. 1997. Active efflux of bile salts by Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:2512-2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomson, S. V. 1986. The role of the stigma in fire blight infections. Phytopathology 76:476-482. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomson, S. V., M. N. Schroth, W. J. Moller, and W. O. Reil. 1975. Occurrence of fire blight of pears in relation to weather and epiphytic populations of Erwinia amylovora. Phytopathology 65:353-358. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Treutter, D. 2001. Biosynthesis of phenolic compounds and its regulation in apple. Plant Growth Regul. 34:71-89. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tseng, T. T., K. S. Gratwick, J. Kollman, D. Park, D. H. Nies, A. Goffeau, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1999. The RND permease superfamily: an ancient, ubiquitous and diverse family that includes human disease and development proteins. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1:107-125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Bambeke, F., E. Balzi, and P. M. Tulkens,. 2000. Antibiotic efflux pumps. Biochem. Pharmacol. 60:457-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vanneste, J. L., and S. Eden-Green. 2000. Migration of Erwinia amylovora in host plant tissue, p. 9-36. In J. L. Vanneste (ed.), Fire blight: the disease and its causative agent, Erwinia amylovora. CABI Publishing, Oxon, United Kingdom.

- 53.Vanneste, J. L., J. Yu, and S. V. Beer. 1992. Role of antibiotic production by Erwinia herbicola Eh252 in biological control of Erwinia amylovora. J. Bacteriol. 174:2785-2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walsh, C. 2000. Molecular mechanisms that confer antibacterial drug resistance. Nature 406:775-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson, K. 1994. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria, p. 2.4.1-2.4.5. In R. Ausubel, R. E. Brent, D. D. Kingston, J. G. Moore, J. Seidman, A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Wilson, K. J., A. Sessitsch, J. C. Corbo, K. E. Giller, A. D. L. Akkermans, and R. A. Jefferson. 1995. Glucuronidase (GUS) transposons for ecological and genetic studies of rhizobia and other Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology 141:1691-1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilson, M., H. A. S. Epton, and D. C. Sigee. 1989. Erwinia amylovora infection of hawthorn blossom. II. The stigma. J. Phytopathol. 127:15-28. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson, M., H. A. S. Epton, and D. C. Sigee. 1990. Erwinia amylovora infection of hawthorn blossom. III. The nectary. J. Phytopathol. 128:62-74. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson, M., and S. E. Lindow. 1993. Interactions between the biological control agent Pseudomonas fluorescens A506 and Erwinia amylovora in pear blossoms. Phytopathology 83:117-123. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wodzinski, R. S., and J. P. Paulin. 1994. Frequency and diversity of antibiotic production by putative Erwinia herbicola strains. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 76:603-607. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wright, S. A., C. H. Zumoff, L. Schneider, and S. V. Beer. 2001. Pantoea agglomerans strain EH318 produces two antibiotics that inhibit Erwinia amylovora in vitro. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:284-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xiao, Y., Y. Lu, S. Heu, and S. W. Hutcheson. 1992. Organization and environmental regulation of the Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae 61 hrp cluster. J. Bacteriol. 174:1734-1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zgurskaya, H. I., and H. Nikaido. 2000. Multi-drug resistance mechanisms: drug efflux across two membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 37:219-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]