Abstract

Spinal posture and the resultant changes during the entire pubertal growth period have not been reported previously. No cohort study has focused on the development of spinal posture during both the ascending and the descending phase of peak growth of the spine. The growth and development of a population-based cohort of 1060 children was followed up for a period of 11 years. The children were examined 5 times, at the ages of 11, 12, 13, 14 and 22 years. A total of 430 subjects participated in the final examination. Sagittal spinal profiles were determined using spinal pantography by the same physician throughout the study. Thoracic kyphosis was more prominent in males at all examinations. The increasing tendency towards thoracic kyphosis continued in men, but not in women. The degree of lumbar lordosis was constant during puberty and young adulthood. Women were more lordotic at all ages. Thoracic hyperkyphosis of ≥45° was as prevalent in boys as girls at 14 years, but significantly (P<0.0001) more prevalent in men (9.6%) than in women (0.9%) at 22 years. The degree of mean thoracic kyphosis and the prevalence of hyperkyphosis increased in men during the descending phase of peak growth of the spine, but decreased in women.

Keywords: Spinal posture, Thoracic kyphosis, Lumbar lordosis, Thoracic hyperkyphosis, Pubertal growth

Introduction

Adolescent spinal posture during the growth phase to young adulthood has not been thoroughly investigated. As part of a comprehensive population-based study programme, the opportunity was taken to focus mainly on determining predictors of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis [1,2,3,7], and spinal posture was also measured [5,6]. The children were examined 5 times, at the ages of 11, 12, 13, 14 and 22 years, using spinal pantography [7]. In the present study, we report the development of spinal posture during the ascending and descending phase of peak growth of the spine in a follow-up period of 11 years.

Materials and methods

The population of this study comprised all the fourth-grade school children of the western school district of Helsinki, Finland, in the spring of 1986. The sample, design and baseline results have been described earlier [1]. Growth and spinal pantography in 1060 children (515 girls and 545 boys) were assessed annually from the average ages of 10.8–13.8 years to discover whether some type of posture or growth profile had any value in predicting the development of thoracic hyperkyphosis.

A total of 855 children (80.7%) participated in the examination at the average age of 13.8 years. These children were invited for re-examination at the average adult age of 21.9 years. Five participants had died during the follow-up period of 11 years and 45 had no permanent address. Of the 803 adults invited, 430 (208 women and 222 men; 53.5% of those invited, 40.6% of the original cohort) accepted the invitation and were examined by one of the authors. The mean age of the 430 participants was 21.9±0.3 years (range 20.8–23.3 years).

Spinal pantographs were drawn and analysed by the same physician (M.J.N.) throughout the study [7,10]. The reliability of spinal pantography has been shown to be excellent, with an intra-observer correlation coefficient of 0.80 and an inter-observer correlation coefficient of 0.94 for thoracic kyphosis and 0.96 for lumbar lordosis [5]. The repeatability of drawing by pantograph has also been shown to be excellent [intra-class correlation for kyphosis (0.80) and for lordosis (0.70)]. The repeatability of the reading is also satisfactory for thoracic kyphosis (0.92) and for lumbar lordosis (0.86) [4]. Thoracic hyperkyphosis was defined as an angle of ≥45° on pantography [5].

This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Helsinki.

Statistical methods

Predictors of thoracic hyperkyphosis were analyzed with a logistic regression model [6]. The relative risks were expressed as adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Both confounding and effect-modifying factors were entered into the models. Thoracic kyphosis at 14 years, left-handedness [6] and change of thoracic kyphosis from 11 to 14 years of age remained in the final model.

Results

Posture and growth

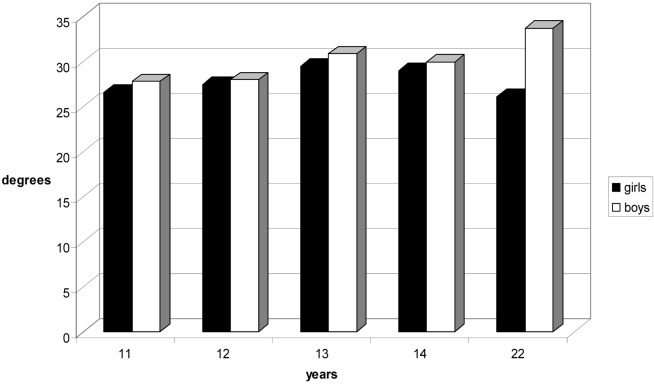

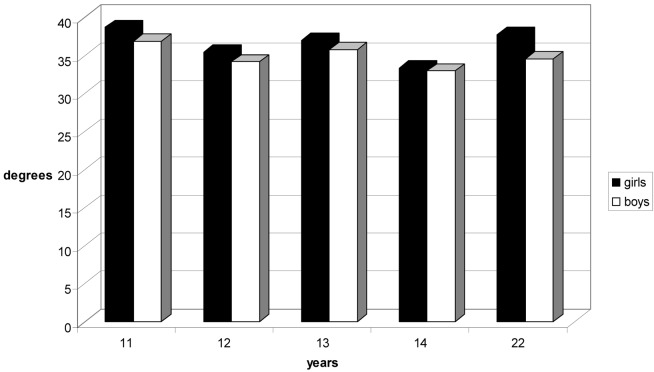

The means, ranges and standard deviations of thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis are shown in Table 1. Mean thoracic kyphosis was more pronounced in boys than girls at all examinations. Male mean thoracic kyphosis was statistically significantly more pronounced at the ages of 11, 13 and 22 years (Fig. 1.). Mean lumbar lordosis was more pronounced in girls than boys at all examinations. Female mean lumbar lordosis was statistically significantly more pronounced at the ages of 11, 12, 13 and 22 years (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Ranges of thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis (degrees) during growth from 11 to 22 years

| Measure | Girls | Boys | Difference between sexes | ||||||

| Age | n | Mean | Range | SD | n | Mean | Range | SD | P-value |

| Thoracic kyphosis | |||||||||

| 11 | 514 | 26.6 | 5–57 | 8.9 | 545 | 27.8 | 4–58 | 8.5 | 0.03 |

| 12 | 476 | 27.5 | 6–61 | 9.6 | 498 | 28.0 | 5–56 | 9.4 | 0.41 |

| 13 | 428 | 29.5 | 2–63 | 9.8 | 473 | 30.9 | 5–61 | 10.4 | 0.04 |

| 14 | 393 | 29.0 | 7–57 | 9.0 | 454 | 30.0 | 6–69 | 9.7 | 0.12 |

| 22 | 208 | 26.1 | 8–57 | 8.9 | 222 | 33.7 | 9–61 | 9.6 | 0.001 |

| Lumbar lordosis | |||||||||

| 11 | 514 | 38.7 | 17–75 | 8.8 | 545 | 36.9 | 11–64 | 8.4 | <0.001 |

| 12 | 476 | 35.5 | 16–61 | 8.3 | 498 | 34.2 | 16–61 | 7.7 | 0.01 |

| 13 | 428 | 37.0 | 3–66 | 8.7 | 473 | 35.8 | 17–58 | 8.0 | 0.03 |

| 14 | 393 | 33.4 | 18–55 | 7.4 | 454 | 33.0 | 15–56 | 7.0 | 0.42 |

| 22 | 208 | 37.8 | 18–72 | 8.1 | 222 | 34.6 | 11–58 | 8.6 | 0.001 |

Fig. 1.

Mean thoracic kyphosis during pubertal growth (girls black columns, boys white columns)

Fig. 2.

Mean lumbar lordosis during pubertal growth (girls black columns, boys white columns)

The increasing tendency of male mean thoracic kyphosis continued during growth from adolescence to young adulthood. The opposite trend was found in women, in whom mean thoracic kyphosis decreased during growth.

The decreasing tendency of mean lumbar lordosis ceased during growth from adolescence to young adulthood in both sexes, but mean lumbar lordosis was most pronounced at the age of 11 years (Fig. 1).

Thoracic hyperkyphosis

The prevalence of thoracic hyperkyphosis of ≥45° was as prevalent in boys as in girls at the age of 14 years, but significantly (P<0.001) more prevalent in men (9.6%) than in women (0.9%) at the age of 22 years.

Predictors of thoracic hyperkyphosis

In men, the degree of thracic kyphosis at 14 years significantly predicted the development of thoracic hyperkyphosis. The odds ratio was 1.09 (95% confidence interval, 1.01–1.17) per increment of thoracic kyphosis at 14 years by a standard deviation (8.9°). Changes in thoracic kyphosis from 11 to 14 years of age or left-handedness were not statistically significant predictors (Table 2).

Table 2.

Odds ratio (OR) of thoracic hyperkyphosis at the age of 22 years and its 95% confidence interval (CI), per increment of 1 SD in thoracic kyphosis at the age of 14 years and change of thoracic kyphosis between 11 and 14 years of age, and according to left-handedness, among 222 males

| Factor | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracic kyphosis at 14 years (mean 29.0, SD 8.9) | 1.09 | 1.01–1.17 |

| Left-handedness (6.5% of 222 men) | 4.14 | 0.97–17.7 |

| Change of thoracic kyphosis from 11 to 14 years (mean 2.6, SD 0.5) | 0.96 | 0.91–1.01 |

Other anthropometric factors such as body height, body mass index, growth velocity or trunk asymmetry showed no association with development or progression of thoracic kyphosis (data not shown).

Discussion

No cohort study that included both the ascending and descending phase of peak growth of the spine has been performed before. The design allowed comparisons between puberty and adulthood in the cohort representative of Finnish schoolchildren. The ultimate aim of this comprehensive study programme was to evaluate screening for idiopathic scoliosis. The agreement between the results of pantography and standing lateral radiographs has been shown to be good for thoracic kyphosis, but poor for lumbar lordosis [5]. Therefore, our results should be interpreted carefully with regard to lumbar lordosis.

The wide physiological variation of spinal posture, already evident at puberty in this cohort [5], was also found in young adults at the age of 22 years. However, thoracic kyphosis was between 20 and 44° in four out of five men and between 16 and 36° in four out of five women. We suggest these as physiological limits of thoracic kyphosis at the age of 22 years, almost in accordance with the previous literature [8].

A major limitation of this study involved the significant loss of participants during the long follow-up period of 11 years. More than half of this cohort (59.4%; 323 boys and 307 girls) did not participate in the young adult assessment. Among those lost were 15 (55%) left-handers, which may have affected the predictive value of left-handedness to thoracic hyperkyphosis, which was found to be stronger at puberty. Apart from left-handedness, none of the baseline anthropometric values of the lost 630 children differed significantly from the corresponding values of those who participated in the final examination (data not shown).

Another limitation of this study was the different phase of growth between girls and boys from 11 until 14 years of age. The mean age at peak height velocity was 12 years among girls and 14 years among boys [2]. In boys, therefore, data on the descending phase of growth were incomplete.

The prevalence of thoracic hyperkyphosis of ≥45° was found to be 10 times (9.6% versus 0.9%) more prevalent in men than women. Male gender was the most powerful determinant of thoracic hyperkyphosis at the age of 22 years. The predictive power of left-handedness as a predictor of thoracic hyperkyphosis diminished during the descending phase growth at late puberty. For ethical reasons, the subjects were not radiographed at the age of 22 years and we cannot report the prevalence of Scheuermann’s disease at this age. At puberty, only one case of progressive thoracic hyperkyphosis due to Scheuermann’s disease was diagnosed in this cohort, and successfully treated with a brace.

The increasing trend of mean thoracic hyperkyphosis during pubertal growth continued in men, but not in women. Men were more kyphotic at all examinations, in accordance with previous studies during the ascending phase of pubertal growth [9,11]. Such a difference was not observed in mean lumbar lordosis, which was rather constant and approximately 35 degrees both at puberty and in young adulthood, 22 years. Women were more lordotic at all examinations.

We conclude that during the descending phase of peak growth of the spine, the degree of mean thoracic kyphosis increases in the male, but decreases in the female. At young adulthood, consequently, thoracic hyperkyphosis is much more prevalent in men than in women.

References

- 1.Nissinen Acta Paediatr Scand. 1989;78:747. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1989.tb11137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nissinen Acta Paediatr Scand. 1993;82:77. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NissinenSpine 19931888434329 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nissinen Spine. 1994;19:1367. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199406000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nissinen Acta Pediatr. 1995;84:308. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nissinen Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:1178. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.6.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nissinen Spine. 2000;25:570. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200003010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.StagnaraSpine 198273357135066 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Widhe Eur Spine J. 2001;10:118. doi: 10.1007/s005860000230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willner J Pedatr Orthop. 1983;3:245. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willner Acta Paediatr Scand. 1983;72:873. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1983.tb09833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]