Abstract

Chordoma is a rare bone tumor that originates from the remnants of the notochord. These tumors have axial distribution particularly at the upper and lower ends of the vertebral column. This paper reports a rare occurrence of a chordoma in the posterior elements of the L5 vertebra. A differential diagnosis of a benign tumor (giant cell tumor, aneurysmal bone cyst or osteoblastoma) was made initially. Other differential diagnoses included plasmacytoma and metastasis. The tumor was removed enbloc. Histopathological examination revealed the tumor mass to be chordoma. There were no clinical or radiological signs of recurrence at 21 months follow-up. Chordomas are tumors of the axial skeleton. However, they may occur in unusual sites in ectopic notochordal tissue. The case is being presented for its unusual site of occurrence.

Keywords: Chordoma, Physaliphorous cells, Lumbar spine, Bone tumors, Vertebrae spinous process

Introduction

Chordomas are low-grade malignant lesions of the axial spine that occur in the remnants of notochordal elements. They constitute 1% of primary bone tumors [11]. They are almost exclusively tumors of the spine, with 60% lesions occurring in the sacrum, 25% in the base of the skull and approximately 15% in the vertebral segments [15]. The most common vertebral segment is cervical followed by lumbar (4%) and thoracic (3%) [15]. Rarely have other sites been reported including scapula and transverse process of L3 [13].

Case report

A 35-year-old male presented with a history of intermittent, dull, poorly localized back pain for 1 year. The patient had received symptomatic treatment elsewhere with no relief. There was no history of weakness, numbness or incontinence. There was no history of any constitutional symptoms such as fever, cough, haemoptysis, anorexia, weight loss, malena etc.

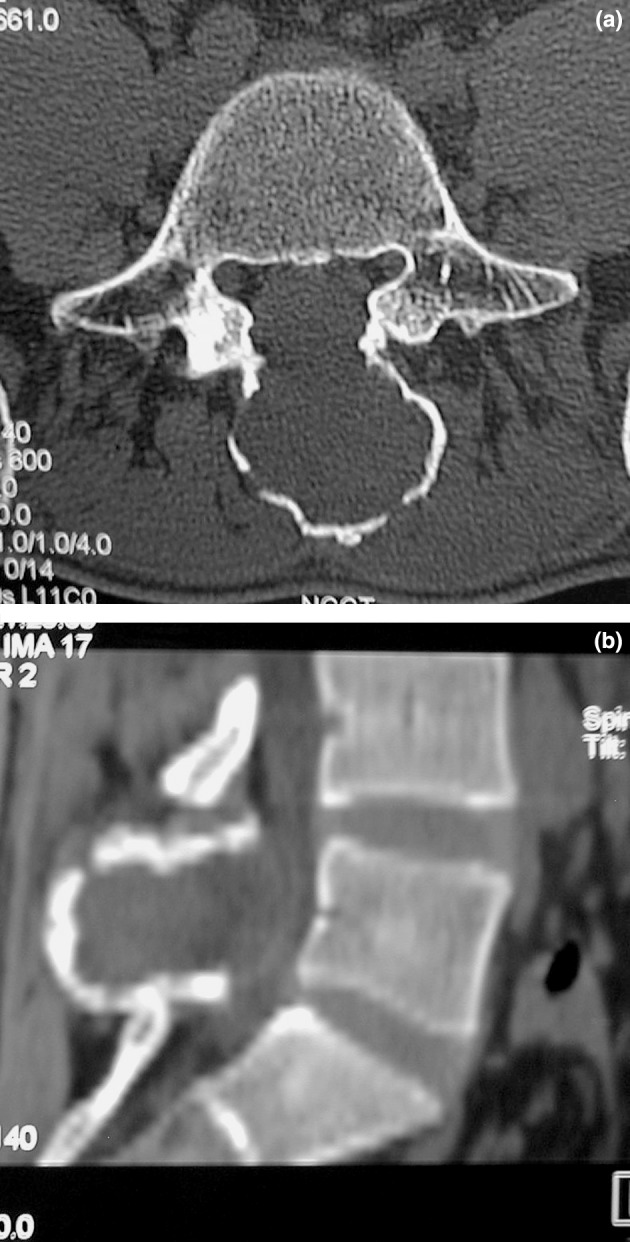

On examination, the spinous process of L5 was prominent but no localized spinal tenderness was elicited. Neurological examination confirmed no deficit. Subsequent radiological evaluation revealed an expansile osteolytic lesion of L5 spinous process and lamina. Computed tomogram of the affected vertebrae confirmed the above findings with the confines of tumor limited to the posterior elements of L5 and no obvious pathological fracture (Fig. 1a, b). CT-guided fine needle aspiration cytology was attempted but was inconclusive. Routine laboratory tests including hematological, blood biochemical and urine analysis were all normal. Clinicoradiological differential diagnosis included benign tumors such as giant cell tumor, aneurysmal bone cyst, or osteoblastoma. Since the tumor was located in a resectable region and since there was a possibility that it may be a locally aggressive benign lesion such as a giant cell tumor with a potential for reoccurrence and neurological deterioration, the patient was taken up for enbloc excision to prevent contamination by spillage.

Fig. 1.

a, b Computed tomogram, transverse section and reconstructed sagital view through L5 demonstrating tumor mass confined to L5 posterior elements (spinous process and lamina).

The posterior elements involved with the tumor were removed enbloc, and the excised specimen sent for histopathology (Fig. 2). Since facets joints were left intact, no fusion or instrumentation was performed. Histology sections revealed the lesion to be a chordoma with cartilage cells (Fig. 3). Surgical margins after resection were reported free of tumor. When last seen at 21 months postoperatively, the patient was painfree and there were no clinical or radiological signs suggestive of recurrence or instability.

Fig. 2.

Image of the specimen after enbloc excision.

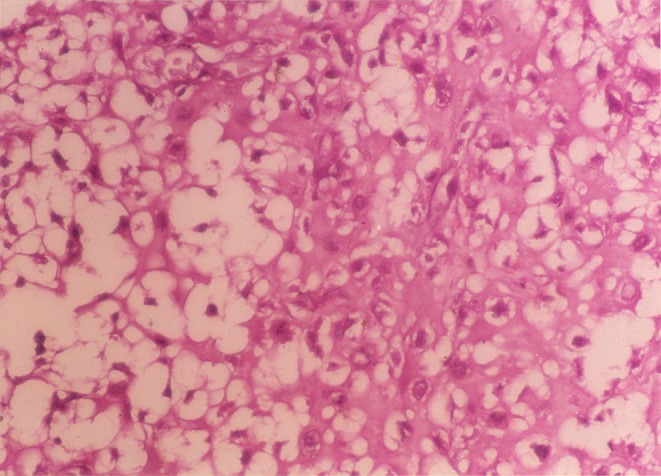

Fig. 3.

Chordoma L5 posterior elements; (H&E, 400) physaliphorous cells with vacuolated cytoplasm and prominent vesicular nucleus.

Discussion

The common benign tumors of the posterior elements of the spine are osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma, neurofibroma, giant cell tumor and aneurysmal bone cyst [8]. Non-tumorous conditions like tuberculosis sometimes cause erosion or destruction of pedicle but usually a large paravertebral abscess is associated. In the malignant group metastasis, solitary plasmacytomas and multiple myeloma involve pedicles early [8, 14]. Other rare possibilities in mobile spine are chondroblastoma, chordomas, or chondrosarcomas [5].

The incidence of chordoma is stated to be 0.5 per million [7]. They originate from notochordal remnants represented in adults mostly as nucleus pulposus. They form 1–4% of all primary bone tumors and 6% of all malignant bone tumors [7]. They predominate in men (2:1) and most patients are between 30 years and 70 years of age [15]. The tumor involves the axial regions of body at the sacrum level (60%), intracranial regions of skull (25%) and spine (15%) [15]. In the vertebral bodies, C2 is a relatively common site [15]. In men in their fifth decade of life, the lesion appears to have a predilection for the L4 and L3, whereas L3 is favored in the seventh decade of life [1, 3, 10, 14].

Vertebral chordomas when small are confined to the body with extension of tumor posteriorly to compress the spinal cord. In more advanced cases, lesions may spread along the posterior longitudinal ligament or by direct extension through the intervertebral disc. The posterior element involvement in chordoma is usually after involvement of the spinal canal [15]. This case of chordoma was confined to a lumbar spinous process, a primary site which to our best of knowledge has never been reported in the literature. It is not clear how the chordoma would arise at a site distant from the notochordal column. Its unusual localization suggests its origin in an ectopic cordal focus as suggested by Kamal [13]. He described chordoma of the L3 transverse process arising from ectopic cordal focus, as no evidence of attachment of tumor mass to the vertebral body could be found during surgery in his case [13]. He cites instances of aberrant chordal tissue within the vertebral body and vertebral surfaces but gives no specific reason for the chordoma occuring at sites away from the focus of origin of the notochord in the vertebral column [13]. Similar observations were made by Higinbotham et al. (1967) who reported primary scapular chordoma [13]. We did not find any filamentous attachments of the tumor to an origin within a vertebral body intraoperatively ruling out any origin from vertebral body.

Histologically, the tumor showed lobules separated by fibrous bands. Cells were arranged in syncytial nests and cords lying in pink mucinous stroma. Typical physaliphorous cells were seen (Fig. 3). Nuclear pleomorphism was minimal. Few multinucleated tumor cells were present. No areas of soft tissue infiltration were seen. In areas of cartilaginous differentiation, the tumor cells were located in lacunae separated from each other by abundant hyaline substance. These chondroid areas merged imperceptibly with the typical chordoid areas.

For further characterization of tumor immunoperoxidase staining for cytokeratin (CK), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and S-100 were performed by streptavidinbiotin peroxidase technique using universal detection kit (IMMUNOTECH) [2]. The tumor tested positive with S-100 staining. However, staining for CK and EMA was focal and mild. Chordomas usually stain positively for cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen. Cytokeratin positivity has been found to vary from 80% to 100% and epithelial membrane antigen from 20% to 80% of cases [16, 17]. Chondrosarcomas are characteristically cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen negative. Both typical chordoma and chondrosarcoma stain positive for S-100 [12]. Our case stained positively for S-100. Cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen staining was mild and focal. Despite the less intense staining for cytokeratin and EMA, the possibility of chordoma with cartilaginous differentiation is strong, as morphologically, our case had typical physaliphorous cells and cells arranged in syncytial nests [9]. On the contrary, cells are dispersed singly and form one cell layer thin cords in chondrosarcoma. Typical physaliphorous cells are never seen in chondrosarcoma.

More recently, a distinct condition described as ‘intraosseous benign notochordal cell tumors’ has been recognized [18]. They have anatomical distribution identical to that of classic chordomas. It is believed that they undergo malignant transformation to classic chordomas. However, they lack typical physaliphorous cells and intercellular myxoid matrix.

It is generally agreed that radical resection of the tumor is the only curative procedure [6]. Complete excision of the tumor according to oncologic criteria can be hampered by extension of tumor and by anatomic constraints in the mobile spine [4]. Enbloc excision of the lesion, sometimes combined with radiation therapy as an adjuvant, provides best results [4]. Radiation therapy is also used for reoccurrence [10]. Chemotherapy has no proven benefit in the treatment of chordoma. Since the tumor was localized to L5 spinous process and lamina, an enbloc excision of the posterior elements with healthy margins achieved this aim. A 21 months follow-up revealed no local or distant recurrence.

References

- 1.Abdelwahab IF, O’Leary PF, Steiner GC, Zwass A. Case report 357. Skeletal Radiol. 1986;15:242–246. doi: 10.1007/BF00354069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bancroft JD, Stevens A. Theory and practice of histopathological techniques. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996. p. 462. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bas T, Bas P, Prieto M, Romas V, Bas JL, Espinosa C. A lumbar chordoma treated with a wide resection. Eur Spine. 1994;3:115–117. doi: 10.1007/BF02221451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boriani S, Chevalley F, Weinstein JN, Biagini R, Campanacci L, De Iure F, Piccill P. Chordoma of the spine above the sacrum. Treatment and outcome in 21 cases. Spine. 1996;21(13):1569–1577. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199607010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boriani S, De lure F, Campanacci L, Gasbarrini A, Bandiera S, Biagini R, Bertoni F, Picci P. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the mobile spine: report on 41 cases. Spine. 2001;26(1):27–35. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200101010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boriani S, Weinstein JN, Biagini R. Primary bone tumors of the spine. Terminology and surgical staging. Spine. 1997;22(9):1036–1044. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199705010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosma JJD, Pigott TJD, Pennie BH, Jaffray DC. En bloc removal of the lower vertebral body for chordoma- report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:284–291. doi: 10.3171/spi.2001.94.2.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman S, Nakielny R. Aids to radiological differential diagnosis. Bangalore/London: Prism Books. WB Saunders Company; 1995. p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heffelfinger MJ, Dahin DC, MacCarty CS, Beabout JW. Chordomas and cartilaginous tumors of the base of the skull. Cancer. 1973;32:410–420. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197308)32:2<410::aid-cncr2820320219>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu KY, Zucherman JF, Mortensen N, Johnston JO, Gartland J. Follow-up evaluation of resected lumbar vertebal chordoma over 11 years. A case report. Spine. 2000;25(19):2537–2540. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200010010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huvos AG. Chordoma Bone tumors: diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1991. pp. 599–623. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jefferey PB, Biava CG, Davis RL. Chondroid chordoma A hyalinized chordoma without cartilaginous differentiation. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;103:271–277. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/103.3.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamal MF, Farah GR, Malkawi HM, Khammash HM. Tumores rari et inusitati. Chordoma in a lumbar vertebral transverse process: a case report and review of literature. Clin Oncol. 1984;10(2):167–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mc Lain RF, Weinstein JN. Solitary plasmacytomas of the spine: a review of 84 cases. J Spinal Disord. 1989;2(2):69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirra JM. Chordoma Bone tumors. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1989. pp. 648–690. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell A, Scheithauer BW, Unni KK, Forsyth PJ, Wold LE, McGivney DJ. Chordoma and chondroid neoplasms of the spheno-occiput An immunohistochemical study of 41 cases with prognostic and nosologic implications. Cancer. 1993;72:2943–2949. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931115)72:10<2943::aid-cncr2820721014>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutherford GS, Davies AG. Chordomas—ultrastructure and immunohistochemistry: A report based on the examination of six cases. Histopathol. 1987;11:775–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1987.tb01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaguchi T, Suzuki S, Ishiiwa H, Shimizu K, Ueda Y. Benign notochordal cell tumors A comparative histological study of benign notochordal cell tumors, classic chordomas, and notochordal vestiges of fetal intervertebral discs. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(6):756–761. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000126058.18669.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]