Abstract

Objectives

The goal of this paper was to articulate and describe family communication patterns that give shape to four types of family caregivers: Manager, Carrier, Partner, and Loner.

Data Sources

Case studies of oncology family caregivers and hospice patients were selected from data collected as part of a larger, randomized controlled trial aimed at assessing family participation in interdisciplinary team meetings.

Conclusion

Each caregiver type demonstrates essential communication traits with nurses and team members; an ability to recognize these caregiver types will facilitate targeted interventions to decrease family oncology caregiver burden.

Implications for Nursing Practice

By becoming familiar with caregiver types, oncology nurses will be better able to address family oncology caregiver burden and the conflicts arising from family communication challenges. With an understanding of family communication patterns and its impact on caregiver burden, nurses can aid patient, family, and team to best optimize all quality of life domains for patient as well as the lead family caregiver.

Clinical communication with caregivers is considered instrumental in establishing and promoting caregiver quality of life [1]. As other articles in this special issue highlight, cancer care impacts all four dimensions of the caregiver’s quality of life. A caregiver’s quality of life is a product of overall physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being [2, 3]. Physical well-being involves the caregiver’s ability to perform caregiving tasks and includes strength, fatigue, and appetite. Psychological well-being reveals cognitive changes, such as observable depression, anxiety about being able to provide quality care, and distress from caregiving burden. Similarly, social well-being characterizes changes in roles or relationships and variation in affection or appearance. A caregiver’s spiritual well-being encompasses both religiosity or transcendence or can include feelings of hopelessness.

Family caregivers are important collaborators during cancer care because they often provide patient information (e.g., medical history, patient preferences), receive directions from the team (e.g., medication instructions, care tasks to be done), and facilitate communication between the patient, healthcare care providers, and other family members [4]. Family members look to oncology nurses for information and are more likely to receive cancer information from health care providers than patients themselves [5, 6]. Typically, conversations with caregivers about cancer focus on the medical treatment plan, the circumstances surrounding the cancer and prognosis, and psychosocial reactions [7]. A nurse’s task goals include communicating caring and ensuring that the family understands and follows recommendations [7].

Although a relational approach with caregivers has been recommended to ensure shared decision-making between clinicians, patients, and family caregivers [8], communicating with family members can be problematic. Following a cancer diagnosis, some family members avoid discussing emotional and information issues about cancer with each other [9]. As a result, nurse assessment of the caregiver’s knowledge of the disease trajectory can be difficult, as it may be different among family members within the same family, and in many cases there is a conflict in informational needs between the patient and the family [10]. Because of the variation in the type of communication valued within a family, the impact of how family members talk to each other about cancer varies as well [9]. Determining appropriate interventions for family members may be dependent upon the family system and its impact on the family caregiver.

Family Communication Patterns Theory details how family conversation and family conformity range from high to low to form specific family communication patterns [11–15]. First, families have rules that govern appropriate topics for family conversation. Family conversation can vary from free, spontaneous interaction between family members (high) to limitations on family topics and time spent communicating with each other (low) [16]. Families with high family conversation patterns talk openly about death, dying, cancer, and illness. Families with high communication prior to the disease maintain the pattern throughout the illness as the situation highlights preexisting interaction patterns [17]. On the other hand, families with low family conversation patterns do not engage in discussions about illness and are able to make decisions without talking about the disease. By avoiding talk about cancer, some family caregivers feel they are protecting the patient from sad conversations [9]. Families who have a prior history of family communication constraints are more likely to experience family conflict during cancer care [18].

The second dimension of the family communication pattern is family conformity, established by a hierarchy within the family structure. Family members with high family conformity have uniform beliefs and family values that emphasize family harmony. However, conformity in family communication does not always equate with family agreement or open communication [19]. Hierarchical roles within the family are often emphasized over conversation and disclosure. Family caregivers of lung cancer patients reported that avoiding the topic of cancer was one way of maintaining family standards, recognizing that the family’s history of communication influenced their approach to communicate about cancer [9]. In some instances, the emotional toll of the situation was considered an unacceptable display of family communication [9]. Alternatively, families with low family conformity have little emphasis on obedience to parents/elders [20]. For example, avoiding communication about cancer is a tactic used by some families to exclude certain family members from decision-making [9].

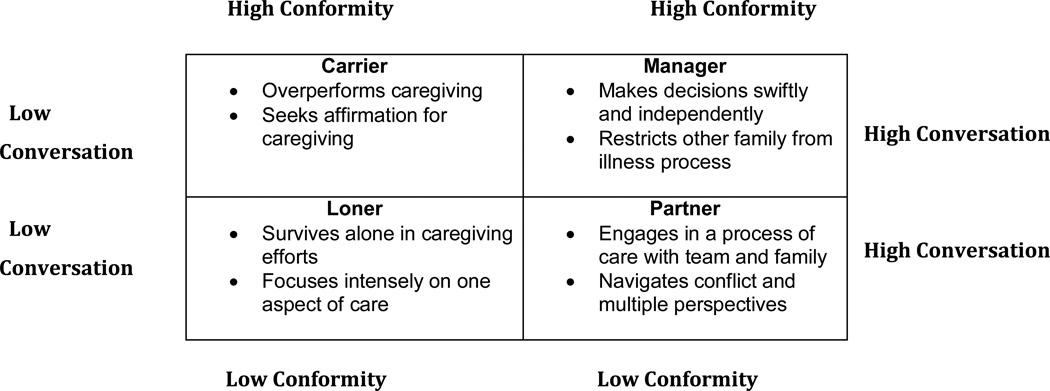

Our early work examined hospice family caregiver talk about family-related concerns during caregiving [19]. Caregiver talk revealed burden resulting from family communication patterns, advancing a typology for the ways caregivers experience caregiving responsibility within their family setting. Namely, Manager, Carrier, Partner, and Loner caregiver types emerged as a result of the burden produced by family communication patterns. The Manager is derived from a family that values high conformity of attitudes, values, and behavior, and also engages in frequent conversation. High conformity for the Manager’s family limits the range of conversational topics however. The Carrier also comes from a high conformity family, but one that is low in conversation frequency and topic variability. A Partner caregiver is part of a family that shares low conformity, or high diversity in attitudes and beliefs, and also high conversation in terms of topic diversity and frequency of interaction. A family very low in conformity as well as conversation produces the Loner caregiver [19]. Case studies depicting each caregiver type are presented to identify essential characteristics of clinical communication and distinguish interventions appropriate for each type.

Methods

Case studies presented here were selected from data collected as part of a randomized controlled trial funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (R01NR011472, Parker Oliver, PI) aimed at assessing the clinical benefits of family participation in hospice team meetings. Family caregivers, patients, and staff were recruited from a hospice agency in the Midwestern United States. The Institutional Review Board of the supporting university approved the study.

Hospice staff provided referrals to a Graduate Research Assistant (GRA) who then contacted patients and caregivers for consent. Upon consent, baseline measures were taken and caregivers randomized for the intervention were provided with a webcam (when necessary) and a password to access web-based video-conferencing software. Caregivers were invited to use video-conferencing to participate in team meetings hosted by hospice staff. The goal of the meeting was to review the patient’s plan of care and facilitate questions and answers between caregivers and staff. A random selection of videoconferences were recorded and transcribed. A grounded theory approach was used to review the transcripts [21].

Two instruments were used to measure caregiver outcomes. The Caregiver Quality of Life Index Revised (CQLI-R) was used to measure caregivers’ quality of social life, with lower scores reflecting lower quality social life [22]. A 3-item family subscale from the Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS) was used to measure primary family networks, with higher scores representing larger family networks [23]. According to the LSNS, a score of 6 or less represents fewer than 2 family members who can be counted on for support and are considered socially isolated. Caregivers reporting scores of 12 or more had 9 or more family members for support.

The GRA contacted caregivers every 15 days to repeat the measures. Additionally, the GRA conducted a bereavement interview 15 days after the patient’s death. As part of the bereavement interview, caregivers were asked to use a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being the best, to rate their overall satisfaction with the hospice team's pain management for their loved one. Demographics were also collected.

To select case studies we reviewed family caregivers of cancer patients who participated in videoconferences. At the time of manuscript preparation 10 cases were identified. Three steps were used to initially identify caregivers who could be typed as one of four caregivers: Loner, Carrier, Manager, and Partner. First, we examined LSNS scores to determine each caregiver’s primary family network. Second, we examined the caregiver’s reported quality of social life. By comparing LSNS and CLQI-R scores, we were able to gauge family networks in terms of number and frequency of contact as well as the quality of the interactions. Finally, we reviewed bereavement interviews and recorded interactions with hospice staff and considered caregiver demographics. In all cases, caregiver names have been changed to protect confidentiality.

Results

Figure 1 provides an overview of the Manager, Carrier, Partner, and Loner caregiver types discussed below.

Figure 1.

Overview of Oncology Family Caregiver Types

Case 1 – The Manager Caregiver

Mr. Bee and Mrs. Glenn are Caucasian siblings, brother (64 years) and sister (67 years), caring for their mother who resided in a nursing home. Mrs. Glenn had some college education and was retired. Mr. Bee completed a GED and was still working part-time. Both siblings were married.

Quality of Life and Family Network Measures

A total of six repeated measures using the CQOL-R and LSNS were taken. Mrs. Glenn’s first three assessments (time 1, 2, and 3) on the CQOL-R yielded an average score of 6.0 which indicated moderate quality of social life, but time 4 measure (4.0) indicated a substantially lower quality of social life. Meanwhile, Mr. Bee’s first three assessments (time 1, 2, and 3) on the CQOL-R yielded an average score of 7.6, with his time 4 assessment (8.0) depicting a much higher quality of social life than his sibling counterpart. Average assessment at time 5 and 6 demonstrated higher quality of social life for Mrs. Glenn (7.5); yet lower quality of social life for Mr. Bee (5.5). Repeated measures on the CQOL-R over the duration of the study suggest a negative correlation between the two caregivers, with Mrs. Glenn’s quality of social life improving and Mr. Bee’s quality of social life worsening.

Likewise, Mrs. Glenn’s first three assessments on the LSNS yielded an average score of 11.4 compared to Mr. Bee’s average of 10.0, depicting that she reported a slightly stronger family network than Mr. Bee. At time 4 assessment, Mrs. Glenn’s reported family network decreased to its lowest level (9.0) and her brother’s family network increased to its highest level (12.0). Average assessment scores for time 5 and 6 depicted a return to original assessment levels for Mrs. Glenn (11.5) and Mr. Bee (10.0). Although time 4 assessment showed the biggest difference between the two siblings over the duration of the study, Mrs. Glenn reported an overall stronger family network than Mr. Bee.

Clinical Communication with healthcare team

Mr. Bee and Mrs. Glenn participated together in two team meetings. During team meetings, hospice staff inquired about the patient’s quality of life domains. Questions were asked about their mother’s adjustment to a new nursing home (psychological) and signs of pain (physical), and staff also shared reports that their mother spent time in the television room (social) and that a local pastor planned to visit the patient (spiritual). However, information about Mr. Bee and Mrs. Glenn’s quality of life during hospice caregiving was limited. When asked about her mother’s transition to the nursing home, Mrs. Glenn commented: “I’m better with things. Those days I talked to you were not good for me. It wasn’t about her. It was me.” However, staff did not question her further about this reference to distress. Generally, Mr. Bee and Mrs. Glenn did not initiate concerns and only asked for clarification or provided their own updates on patient care. Mrs. Glenn positioned herself as the dominant communicator, both verbally and nonverbally, telling the team: “My brother is here with me and we have no questions.” Although Mr. Bee was present for both team meetings, he did not say anything and sat in the seat furthest from the camera and microphone, positioning his sister to speak for him.

Discussion

Mrs. Glenn emerged as the dominant family figure during clinical communication with hospice staff. She served as self-appointed family spokesperson, providing decisive decision-making and limiting open family communication with Mr. Bee. With an emphasis on family structure, Mr. Bee emphasized family obligations (conformity) over conversation. His need to communicate was diminished by the preservation of existing family patterns. When asked if he was able to pose questions during team conferences, Mr. Bee reported that his “sister did most of it” and that he “was just there to kinda help her out a little bit.” Not surprisingly, Mrs. Glenn reported an overall stronger family network than Mr. Bee. She continued to use “we” language about caregiving responsibilities but was the self-appointed family spokesperson in all clinical communication with staff.

Summary of Key Points

Manager Caregivers may have other family members present but disallow their participation by dominating communication. Disparities in educational achievement between family members may influence this pattern.

As dominant family spokesperson, Manager Caregivers prioritize swift decision-making.

Staff should initiate participation of other family members present, particularly those who remain silent during clinical interactions.

Case 2 – The Carrier Caregiver

Ms. Wilson is an African-American woman in her 60s caring for her sister who was under hospice care for lung cancer with brain metastases. She had some outside employment responsibilities, had attended college, and was separated from her partner. In order to provide care to her sister, Ms. Wilson relocated her sister to her home.

Quality of Life and Family Network Measures

Two repeated measures were taken for Ms. Wilson. On her initial assessment (time 1), her average score on the CQOL-R for social quality of life was 10.0 which indicates high quality, but time 2 (9.0) was slightly lower. Repeated measures on the LSNS over the duration of the study showed no change, with her average score (10.0) depicting a moderate family network consisting of 3–4 family members.

Clinical Communication with healthcare team

Ms. Wilson participated in one team meeting with hospice staff. The focal point of the discussion was her sister’s “uncontrollable” anxiety and staff questioned Ms. Wilson about her sister’s fear of dying (psychological well-being), people she may need/want to see (social work and spiritual issues), and reviewed pain management (physical well-being). Ms. Wilson shared that her sister’s anxiety stemmed from her inability to be in her own home. Although Ms. Wilson shared that she often prays with her sister to help calm her down, the hospice team did not address Ms. Wilson’s own spiritual, psychological, physical, or social burden. In her communication with staff, Ms. Wilson tended to default to others in her decision-making or make a decision and then seek social support from the hospice team. Unlike the Manager Caregiver, she expressed concern and asked questions about her duties as a caregiver. She was also unique from other caregiver types by immediately initiating a concern rather than waiting to be asked if she had any concerns. She mainly used “I” language in describing caregiving and made it clear to the team that she needed support, as she was uncertain about her caregiving role.

Discussion

While Ms. Wilson reported a moderate family network of 3–4 people, she conveyed that she was the primary caregiver for her sister by focusing only on her role as caregiver and disclosing little about assistance from other family members. Unique to the Carrier Caregiver, her caregiving burden came from efforts to follow directions from her sister and make arrangements for her sister to visit her home. Decision-making about care was up to her sister and Ms. Wilson’s job was to carry out her sister’s wishes. As a result, most Carrier Caregivers are acutely aware of their ability to meet patient needs and seek confirmation from hospice staff assessing his or her performance. With an emphasis on preservation of family, conformity outweighed family conversation and Ms. Wilson reported that her main concern was maintaining her sister’s dignity throughout the dying process. Self-imposed pressure to do well resulted in a lower quality of life for Ms. Wilson as her sister became more ill. Ms. Wilson’s obligation to family conformity likely resulted in her position as caregiver.

Summary of Key Points

Evidence of over-performance of the caregiver role is highlighted by Carrier Caregivers who work to demonstrate excellent caregiver performance.

Carrier Caregivers focus almost exclusively on support needs as they attempt to meet the requests of the patient.

Staff should provide accolades and reassurance about the quality of caregiving being provided by the caregiver. Respite care and the provision of care resources, including family mediation, will be important for the Carrier Caregiver who attempts to meet every patient care goal alone.

Case 3 – The Partner Caregiver

Mrs. Terry is a Caucasian woman in her late 50s caring for her mother who resided in a nursing home following a diagnosis of advanced OVCA with metastases to the lung. Mrs. Terry had a graduate degree, was married, and retired.

Quality of Life and Family Network Measures

Only one measure of the CQOL-R and LSNS were taken for Mrs. Terry. On the CQOL-R she reported high quality of social life (9.0 out of 10.0) and high family network of 5–8 family members (11.0 out of 15.0).

Clinical Communication with healthcare team

Mrs. Terry participated in one team meeting with hospice staff. Happiness with her transition to a new place of care (psychological well-being), increased comfort with more frequent attention from health care professionals (social and spiritual well-being), and attention to her disinterest in drinking, inability to swallow pain medication in pill form, diminishing strength, and effects of disease progression (physical well-being) were among the topics shared about her mother. Mrs. Terry inferred that even though she had child care responsibilities for her grandchildren, she had arranged a daily visit to her mother and this was very positively affirmed by various team members—and in so doing Mrs. Terry’s psychological and social well-being as caregiver was included in this meeting. Similarly, Mrs. Terry’s conflict with her brother, Tom, was integrated in the team meeting by the chaplain, providing Mrs. Terry further opportunity to share family conflicts about choosing a hospice agency with the team (social well-being). She presented developments and concerns, but initiated few questions.

Discussion

Mrs. Terry was positioned as a teammate with the hospice staff and reported the highest family network of all other caregiver types. She considered challenges and decisions with the team, and included the perspectives—even if divergent—of family members not present. The Partner Caregiver holds perspective in pursuit of the best patient care possible, knowing that this is not something that can be sought or achieved without the entire family and health care team. This caregiver type becomes a partner not only within her own family, but also with the team. Mrs. Terry used a variety of names and pronouns in describing her mother, her family, and herself. Their identities were not usurped into that of the caregiver, as they are in the Manager Caregiver type, or excluded from the cause, as they are with the Carrier. Her father’s painful cancer death 17 years earlier, plus family interaction patterns which supported high conversation and low conformity, allowed Mrs. Terry to experience the least burdensome type of caregiving.

Summary of Key Points

Partner caregivers engage in processes of problem-solving with other family members and health care team members.

Partner caregivers use “I”"we”, as well as specific name identifiers as they acknowledge and see the burdens that family and team are distributing to achieve optimal patient care.

Staff should focus on including the caregiver in care planning, engaging in dialogue about decision-making, rather than providing information. The opportunity to be part of the care team compliments the Partner Caregiver’s family communication pattern.

Case 4 – The Loner Caregiver

Mrs. Salley is a Caucasian woman in her 70s overseeing care for her husband who lived in a nursing home. She had an undergraduate college degree and was retired.

Quality of Life and Family Network Measures

Two repeated measures were taken for Mrs. Salley. At initial assessment (time 1) on the CQOL-R, Mrs. Salley reported a 3.0, indicating low quality of social life, which was only slightly higher at the time 2 assessment (4.0). Similarly, her average score on the LSNS at time 1 produced a 6, which indicates fewer than 2 family members in her family social network. While this initial score suggests social isolation, Mrs. Salley’s time 2 assessment did increase (8.0).

Clinical Communication with healthcare team

Based on her bereavement interview, we know that Mrs. Salley participated in at least two team meetings. While reflecting on her own communication and presence in team meetings, this caregiver remained fixed on the physical well being of her dying spouse. Concerns about a port, CT scan results, steroids, and brand of pain medication prompted extensive question and answer periods with various team members during her husband’s care. In describing her husband’s level of peace upon dying (spiritual and psychological well being), she noted an 8 out of 10---the lowest number provided by any of our caregiver types during bereavement interviews. She described bringing a specific complaint and question to the team, depicting the team “doing things” and explaining that she worked to “have a say” in these actions. This communication suggests that Mrs. Salley interacted with the team as a disempowered person, awaiting deliberations over her anxious concerns. Mrs. Salley employed descriptions of her family that revealed their separateness from her in caregiving and loss (i.e."they got some answers to questions they were asking”).

Discussion

Mrs. Salley’s initial report of two or less family members and a consistently low quality of social life in relation to the family network is consonant with her lack of disclosure about any caregiver support provided by other family during the illness experience. Distinctive to this caregiver is the inability to identify as part of a team with family or healthcare professionals. The Loner Caregiver primarily experiences care as one acute crisis moment after another; this dynamic is heightened by their perceived isolation. The burden for this caregiver is redoubled because of her inability to enter into ongoing discussion about multiple care matters, as there is a proclivity to fixate on one quality of life domain at the expense of others, as well as the caregiver’s own quality of life. There is no demonstrated effort placed on family conversation or conformity, as the Loner views these variables as unreliable or simply not present in his or her family system. As a result, Mrs. Salley performed exclusively as the caregiver, according to her descriptions upon bereavement.

Summary of Key Points

Loner Caregiver questions care surrounding one quality of life dimension rather than initiating their own problem-solving processes about holistic care.

Family members are identified as separates in caregiver descriptions (i.e."they”).

Staff should consistently engage this caregiver in one-on-one interactions to integrate quality of life domains for patient and caregiver, increasing health literacy.

Research implications and future needs

Family caregivers interact regularly with the healthcare team, providing and receiving information from healthcare providers, delivering daily care, and influencing treatment decisions [5]. Some family caregivers report avoiding talk about cancer because they feel that they cannot do it well and lack self-efficacy to have a family conversation about cancer [9]. Avoiding the topic of cancer is often the caregiver’s attempt to reduce psychological distress and prohibit uncomfortable discussions with the patient or other family members [24]. Family caregivers also struggle with the competing needs of open communication and avoidance within the family, with the communication divide possible between the patient and family or among family members [9]. These complexities can seem impenetrable for nurses and health care teams pursuing the best care and goal planning for oncology patients.

During cancer care, several barriers exist that prohibit discussions about transitions in care. For example, nurses must decide which team member should initiate conversations, when it is appropriate to suggest a transition in care, whether or not the patient is eligible for transition, and consider treatment options that may prolong aggressive treatments [25]. Nurses have a unique clinical role that makes them the most accessible care provider on the care team, privy to family conversations and ongoing family communication throughout the care trajectory. Recognizing the indicators of a specific family caregiver type, or communication pattern within a family, enables early identification of at-risk caregivers in need of multiple interventions. Identifying a specific caregiver type should help nurses and their teams most appropriately target interventions that will support family oncology caregivers.

The four caregiver types (Manager, Carrier, Partner, and Loner) explicated here should be further studied to assess impact on nursing and team goal planning as well as caregiver burden. As these cases reveal, every caregiver type faces some of the most taxing stressors of life during cancer care for a loved one. No type of caregiver escapes these stressors. But our work in this area and the much longer history of Family Communication Patterns Theory indicates that families with less strict conformity patterns and high conversation are more adaptable and flexible. Likewise, the Partner caregiver (low conformity/high conversation) emerges from families better able to distribute stressors and process decisions and changes along the cancer trajectory.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Award Number R01NR011472 from the National Institute of Nursing Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Elaine Wittenberg-Lyles, University of Kentucky, Markey Cancer Center and Department of Communication, 741 S. Limestone, B357 BBSRB, Lexington, KY 40506-0509.

Joy Goldsmith, Department of Communication, Young Harris College, Young Harris, GA.

Debra Parker Oliver, Curtis and Ann Long Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Missouri.

George Demiris, Biobehavioral Nursing and Health Systems, School of Nursing & Biomedical and Health Informatics, School of Medicine, University of Washington, BNHS-Box 357266, Seattle, WA 98195-7266.

Anna Rankin, Department of Communication, University of Kentucky.

References

- 1.Tamayo GJ, et al. Caring for the caregiver. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(1):E50–E57. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.E50-E57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitrungroter L, Cohen MZ. Quality of life of family caregivers of patients with cancer: a literature review. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33(3):625–632. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.625-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrell B. From research to practice: quality of life assessment in medical oncology. J Support Oncol. 2008;6(5):230–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li H, et al. Families and hospitalized elders: A typology of family care actions. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(1):3–16. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(200002)23:1<3::aid-nur2>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bevan JL, Pecchioni LL. Understanding the impact of family caregiver cancer literacy on patient health outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;71(3):356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koutsopoulou S, et al. A critical review of the evidence for nurses as information providers to cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19(5–6):749–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brataas HV, Thorsnes SL, Hargie O. Themes and goals in cancer outpatient-cancer nurse consultations. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2010;19(2):184–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hubbard G, et al. Treatment decision-making in cancer care: the role of the carer. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19:2023–2031. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caughlin JP, et al. Being open without talking about it: A rhetorical/normative approach to understanding topic avoidance in families after a lung cancer diagnosis. Communication Monographs. 2011;78(4):409–436. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirk I, et al. Perspectives of Vancouver Island Hospice Palliative Care Team members on barriers to communication at the end of life. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2010;12(1):59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koerner AF, Fitzpatrick MA. Family communication patterns theory: A social cognitive approach. In: Braithwaite D, Baxter L, editors. Engaging theories in family communication: Multiple perspectives. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2006. pp. 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris J, et al. Family communication during the cancer experience. J Health Commun. 2009;14(Suppl 1):76–84. doi: 10.1080/10810730902806844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritchie L, Fitzpatrick MA. Family communication patterns: Measuring interpersonal perceptions of interpersonal relationships. Communication Research. 1990;17:523–544. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzpatrick MA, Ritchie L. Communication schemata within the family: Multiple perspectives on family interaction. Human Communication Research. 1994;20:275–301. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLeod J, Chaffee S. Interpersonal approaches to communication research. American Behavioral Scientist. 1973;16:469–499. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzpatrick MA. Family Communication Patterns Theory: Observations on Its Development and Application. Journal of Family Communication. 2004;4(3/4):167–179. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Syren SM, Saveman BI, Benzein EG. Being a family in the midst of living and dying. J Palliat Care. 2006;22(1):26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer BJ, et al. Predictors of family conflict at the end of life: the experience of spouses and adult children of persons with lung cancer. Gerontologist. 50(2):215–225. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wittenberg-Lyles E, et al. The Impact of Family Communication Patterns on Hospice Family Caregivers: A New Typology. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2012;14(1):25–33. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0b013e318233114b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koerner AF, Fitzpatrick MA. Toward a Theory of Family Communication. Communication Theory (10503293) 2002;12(1):70. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Courtney K, et al. Conversion of the Caregiver Quality of Life Index to an interview instrument. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2005;14(5):463–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lubben J, Gironda M. Social Support Networks. In: Osterweil D, Brummel-Smith K, Beck J, editors. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. McGraw Hill: 2000. pp. 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang AY, Siminoff LA. Silence and cancer: why do families and patients fail to communicate? Health Commun. 2003;15(4):415–429. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1504_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill KK, Hacker ED. Helping patients with cancer prepare for hospice. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2010;14(2):180–188. doi: 10.1188/10.CJON.180-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]