Abstract

During the past 30 years various treatment protocols for hangman’s fractures have been attempted. In order to guide the management of hangman’s fractures, different classifications have been introduced. However, opinions on operative or nonoperative treatment have not yet been solidified. To evaluate both conservative and operative management of hangman’s fractures in the published literature and to provide appropriate guidelines for treatment of hangman’s fractures, a systematic review of the literature regarding the management of hangman’s fractures was performed. An English literature search from January 1966 to January 2004 was completed with reference to treatment of hangman’s fractures. The classification for treatment guidance from the literature was also reviewed. Regarding a primary therapy for hangman’s fractures, there were 20 papers (62.5%) that advocated for a conservative treatment and 11 of the remaining 12 papers suggested that conservative treatment was suitable for some stable fractures. The classification of Effendi et al. modified by Levine and Edwards was used widely. Most hangman’s fractures could be managed successfully with traction and external immobilization, especially in Effendi Type I, Type II and Levine-Edwards Type II fractures. It is necessary for Levine-Edwards Type IIa and III fractures to be treated with rigid immobilization. Only for some stable Type I and Levine-Edwards Type II injuries, nonrigid external fixation alone was sufficient. Rigid immobilization alone was necessary for most cases. Surgical stabilization is recommended in unstable cases when there is the possibility of later instability, such as Levine-Edwards Type IIa and III fractures with significant dislocation. The classification system proposed by Effendi et al. and modified by Levine and Edwards provided a clinically reasonable guideline for successful management of hangman’s fractures.

Keywords: Hangman’s fracture, Traumatic spondylolisthesis of C2, Management, Systematic review

Introduction

Hangman’s fractures have been used to describe traumatic spondylolisthesis of C2 since it was initially noted in 1965 by Schneider et al. [31]. It is defined as fractures to the lamina, articular facets, pedicles, or pars of the axis vertebra. Hangman’s fractures are often caused by falling, diving or motor vehicle accidents. Today, the management strategies and the surgical indications for hangman’s fractures are still controversial, particularly for Type II and Type III according to Levine and Edwards [20].

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are now becoming an increasingly accepted means to achieve evidence based conclusions; and the methods can help surgeons to make rational decisions. The lack of adequate trials and publications comparing the efficacy of one way over another for the treatment of hangman’s fractures prompted us to perform an analysis of the literature on this subject. In this evidence-based review, the current literature was examined to determine if there was any significant scientific evidence to support a standard modality for the management of hangman’s fractures. Since classification system is an important tool for guiding treatment of fractures and predicting prognosis, the classification of hangman’s fractures applied and the frequency of classification in the literature were also reviewed.

Materials and methods

Search criteria

Relevant literature search was performed using the most common database of medical literature as shown below:

Medline (Through Pubmed; 1966 to January 2002)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (2004–1)

Current Contents (1996 to January 2004)

The search strings and the number of hits were given in Table 1. The search was performed with limiting factors of “human” and “English language”. Some papers were found by manual methods. Additional articles identified from these references that contained relevant supporting information were then included. The search was performed by one reviewer.

Table 1.

Search strings and number of hits

| Search strings | Medline | Current contents | Cochrane |

|---|---|---|---|

| “spinal injuries” [mh] and “axis” [mh] | 411 | 126 | 0 |

| “spinal cord injuries” [mh] and “axis” [mh] | 201 | 41 | 0 |

| “spinal fractures” [mh] and “axis” [mh] | 262 | 117 | 0 |

| “hangman’s fracture” [tiab] | 113 | 25 | 0 |

| “traumatic spondylolisthesis of C2” [tiab] | 42 | 6 | 0 |

(mh mesh heading, tiab title/abstract)

Inclusion/Exclusion criteria

After excluding identical papers, we carried out a selection of peer-reviewed articles to include. The selected articles should meet the following criteria:

The papers that focused on the treatment of hangman’s fractures were selected regardless of the number of patients.

The articles without a clear description of fracture conditions and therapy were excluded.

If the articles were reported by the same authors [16, 17] or from the same institute [10, 11, 15], the most currently reported paper with detailed and complete clinical data would be included. If an equal number of patients were reported by the same authors [10–13], the articles with the most information were selected. The information extraction of articles was done independently to minimize selection bias and errors.

All abstracts were printed and close-reading was performed by two surgeons with rich experience in spinal surgery. The different information extracted from the same article were compared and reread till the information could be agreed upon. If it was difficult for them to obtain a consensus, a third reviewer was consulted. Finally, a total of 32 papers were selected to review. Full text of each paper was found, then, careful reading and data extraction was done independently by the two surgeons mentioned above. At last, all extracted information were imported into an electronic spread sheet—Microsoft Excel.

Data extraction

In the articles we reviewed, the hangman’s fractures healed with suitable external immobilization were regarded as treated with the conservative method. The patients with combined cervical spine fractures were included in some papers; among them, if surgery was not performed because of hangman’s fractures, then the case was also regarded as managed with conservative method. In cases treated conservatively, the different immobilization was noted and divided into rigid alone, nonrigid alone and both. The number of patients in three groups above was calculated.

If the cases were treated with surgery, the number of patients underwent anterior, posterior and anterior–posterior approach was recorded, respectively.

If a kind of classification system was adopted in an article, the above data was extracted according to the fracture type at the same time. The healing rate in every fracture type was calculated, too.

Classification

Hangman’s fractures were classified based on stability or on the fracture morphology. These classification systems shown in Table 2 may provide the guidelines for treatment.

Table 2.

Classification of hangman’s fracture

| Authors | Year of publication | Basis of classification | Type of hangman’s fracture | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Williams [44] | 1975 | Mechanism of injury | Type one (true hangman’s fractures) | Caused by extension and distraction |

| Type two (axis pedicle fractures) | Caused by extension and compression | |||

| Seljeskog and Chou [32] | 1976 | X-ray studies | Type one | Isolated C2 laminar-pedicle fractures |

| Type two | Typical hangman’s fracture-dislocation without subluxation | |||

| Type three | Typical hangman’s fracture-dislocation With subluxation (Minimal: less than 4 mm; Moderate: more than 4 mm) | |||

| Pepin and Hawkin [27] | 1981 | X-ray Evaluation | Type one (nondisplaced fracture) | Only involved the posterior part |

| Type two (displaced fracture) | The posterior element and the body of C2 were included | |||

| Francis and Fielding [13] | 1981 | Displacement,agulation, and ligamentous in stability | Francis Grade | C2-C3 Displacement C2-C3 Angulations (°) |

| I | < 3.5 <11 | |||

| II | < 3.5 >11 | |||

| III | >3.5 < 0.5 (vertebral width) <11 |

|||

| IV | >3.5 < 0.5 (vertebral width) >11 |

|||

| V | Disc disruption | |||

| Effendi et al. [11] | 1981 | Radiographic signs and the clinical course | Type I | Single hairline fractures of the pedicle of axis |

| Type II | Displacement of the anterior fragment with an abnormal disc below the axis (flexion, extension, spondylolisthesis) | |||

| Type III | Displacement of the anterior element with the body of the axis in the flexed position and the facet joints at C2-3 are dislocated and locked | |||

| Levine and Edwards [20] | 1985 | Mechanism of fractures | Type I | Axial loading and hyperextension |

| Type II | Hyperextension-axial loading force associated with severe flexion | |||

| Type IIa | Flexion-distraction, mild or no displacement but very severe angulation | |||

| Type III | Flexion-compression | |||

| Levine [19] | 1998 | Type Ia | Minimal translation and little or no angulation elongation of the C2 body | |

| Levine and Rhyne [21] | 1991 | Subtypes of Type III | Bipedicular fractures with bilateral facet dislocation Unilateral facet injuries or dislocations bound to a contralateral neural arch fracture Bilateral facet dislocation combined with bilaminar factures of C2 |

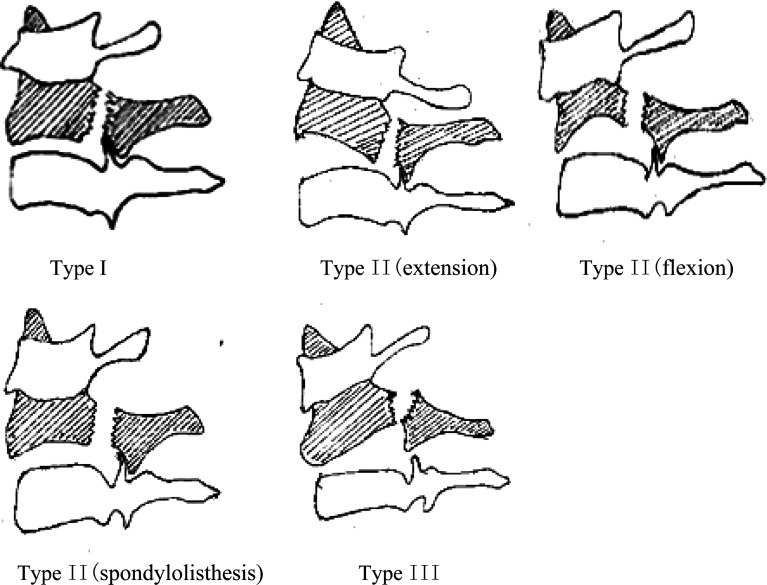

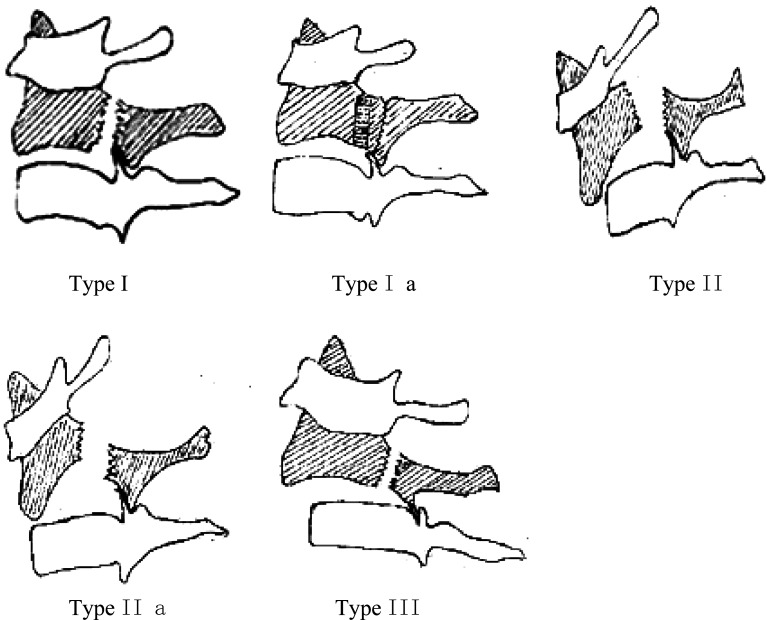

In the current study, the classification systems proposed by Effendi et al. [11] (Fig. 1) and Levine and Edwards [20] (Fig. 2) were used to evaluate the percentage of nonoperative and operative treatment of hangman’s fractures and outcomes.

Fig. 1.

The classification systems of Effendi et al.

Fig. 2.

The classification systems of Levine and Edwards

Stability

The definition of the stability of fractures could provide indications for the management. The criterion of the stability in hangman’s fractures was uncertain. In general, stability was evaluated by the signs of angulation of C2–C3, anterior translation, displacement or diastasis of the fracture on initial lateral films and variations on flexion-extension films. Therefore, the opinions on this topic in the publications we reviewed were also reviewed.

Results

After a screening of abstracts, 32 articles underwent further analysis. There were six reports published before 1980, eight papers published between 1981 and 1989, and nine papers in the 1990s and the 2000s each. The detailed data was listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Data of publication of the management of hangman’s fractures

| Authors No. of patients |

Year of publication | No. of death | Classification | Primary therapy | No. of conservative therapy | Anterior approach | No.of surgery Anterior + posterior | Posterior approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schneider et al.[31] | 1965 | 0 | No | Traction | Minerva jacket (3) | 1 | ||

| 8 | + external immobilization | Cervical brace (2) | ||||||

| Collar (1) | ||||||||

| Halter traction (1) | ||||||||

| Cornish [7] | 1968 | 1 | No | Splint or traction in 3 | Splint (3) | 10 | ||

| 14 | Surgery in 10 | |||||||

| Norrell et al. [26] | 1970 | 0 | Stable | Unstable fracture were | no mentioned therapy | 5 | ||

| 12 | Unstable | treated with operation | ||||||

| Termansen [38] | 1974 | 1 | No | Traction or | Traction +bed rest (10) | 2 | ||

| 19 | external fixation | Plaster caster (5) | ||||||

| Collar (1) | ||||||||

| Brashear et al. [3] | 1975 | 0 | No | Traction + | Rigid immobilization (22) | 1 | C1-3 (3) | |

| 29 | external fixation | Thomas collar (1) | C0-C3 (1) | |||||

| or operated (if large | C2-C3 (1) | |||||||

| displacement remained) | ||||||||

| Seljeskog et al. [32] | 1976 | 3 | A: single fracture of | Traction + | Traction + cervical brace (15) | 1 | ||

| 26 | laminar-pedicle (8) | immobilizatiom | Cervical brace (5) | |||||

| B: true hangman’s | Traction + halo caster + | |||||||

| fracture (18) | Cervical brace (2) | |||||||

| including | ||||||||

| no subluxation (3) | ||||||||

| minimal < 4mm (9) | ||||||||

| moderate (6) | ||||||||

| Franscis et al. [13] | 1981 | 0 | Grade I: 19 | Traction + rigid support (88) | 117 | 4 | C1-3 (2) | |

| 123 | II: 9 | Rigid support (35) | ||||||

| III: 46 | ||||||||

| IV: 42 | ||||||||

| V: 7 | ||||||||

| Effendi et al. [11] | 1981 | 9 | Type I: 85 | Type I: splint | Brace (Type I: 62; II: 17; III: 1) | Type I: 5 | Type I: 17 | |

| 131 | II: 37 | II: immobilization | II: 4 | II: 11 | ||||

| III: 9 | III: if reduced, then | III: 1 | III: 4 | |||||

| immobilized firstly | ||||||||

| Pepin et al. [27] | 1981 | 4 | Type I: 15 | Type I: cervical collar | Brace or collar (38) | |||

| 42 | II: 27 | or brace | ||||||

| II: brace or halo | ||||||||

| Borne et al. [2] | 1984 | 0 | A: stable without | A (rigid collar) | Rigid collar (1) | C1-3 wiring (4) | ||

| 18 | displacement | B (reduction + | ||||||

| B: | immobilization) | |||||||

| stable: with little | ||||||||

| displacement (< 2mm) | ||||||||

| unstable: with mild | ||||||||

| larger displacement | ||||||||

| Roda et al. [29] | 1984 | 0 | Complete dislocation | Reduction + immobilization | Halo cast (1) | |||

| 1 | ||||||||

| Levine and Edwards | 1985 | 5 | Type I: 15 (2 died) | All treated | Type I: | Type III: | ||

| [20] | II: 29 (3 died) | conservatively | Philadelphia collar (6) | C2-3 wiring (3) | ||||

| 52 | IIa: 3 | halo (7) | ||||||

| III: 5 | II: Philadelphia collar (4) | |||||||

| halo (22) | ||||||||

| IIa: halo (3) | ||||||||

| III: halo (2) | ||||||||

| Govender and Charles | 0 | Stable: 32 | Stable: halter traction + | Halo or SOMI (39) | ||||

| [14] | 1987 | Unstable: 7 | collar or SOMI brace | |||||

| 39 | Unstable: skull tong reduction + | |||||||

| collar or SOMI brace | ||||||||

| Bucholz et al. [4] | 1989 | 0 | No | Halo | Halo (12) | |||

| 12 | ||||||||

| Barros [1] | 1990 | 0 | Francis Grade V | Reduction | Halo traction + Minerva cast | |||

| 1 | + immobilization | |||||||

| Rockswold et al. [28] | 0 | No | Halo | Halo failure (7%) | ||||

| 15 | 1990 | |||||||

| Tan et al. [37] | 1992 | 0 | Effendi Type I: 21, | Traction for | Effendi Type I: | |||

| 34 | II: 11, | at least 6 weeks | Philadelphia collar (21) | |||||

| III: 1 | II: Doll’s collar (10) | |||||||

| SOMI (1) | ||||||||

| III: SOMI (1) | ||||||||

| Tuite et al. -[39] | 1992 | 0 | Effendi Type II: 5 | Halo | 5 | |||

| 5 | ||||||||

| Starr and Eismont. | 0 | Levine and Edwards | Traction + halo fixation | Halo (5) | Type II: | |||

| [34] | 1993 | Type I: 2 | patients with complete | O-C3 fixation (1) | ||||

| 6 | II: 4 | quadriplegia not included | ||||||

| Coric et al. [6] | 1996 | 0 | Displacement without | A: nonrigid fixation | A: nonrigid fixation (39) | B: 1 | ||

| 49 | combined cervical | B: nonrigid and | B: nonrigid fixation (6) | |||||

| injuries | halo fixation | halo (3) | ||||||

| A: less than 6 mm (39) | ||||||||

| B: more than 6 mm (10) | ||||||||

| Choi et al. [5] | 1997 | 0 | Levine and Edwards | Reduced + halo | C2-3 plate + C1-3 fusion | |||

| 1 | Type III | |||||||

| Greene et al. [15] | 1997 | 2 | Effendi Type I: 53 | Reduction + external fixation | Halo (56) | Surgery (7) | ||

| 74 | II: 20 | SOMI (6) | no said approach | |||||

| III: 1 | Philadelphia collar (3) | |||||||

| Francis Grade I: 48 | ||||||||

| II: 12 | ||||||||

| III: 11 | ||||||||

| IV: 3 | ||||||||

| V: 0 | ||||||||

| Verheggen and | 1998 | 0 | Levine and Edwards | Operation | Transpedicle screw (16) | |||

| Jansen [41] | Type II: 5 | |||||||

| 16 | IIa: 8 | |||||||

| III: 3 | ||||||||

| Samaha et al. [30] | 2000 | 0 | Group 1–3 | Minerva: | Minerva (15) | Plate (9) | ||

| 24 | displacement < 3 mm | |||||||

| and no kyphosis or lordosis | ||||||||

| and stable on dynamic film | ||||||||

| Surgery: | ||||||||

| displacement ≥3 mm | ||||||||

| and kyphosis ≥15° | ||||||||

| or lordosis ≥5° | ||||||||

| Taller et al. [36] | 2000 | 0 | No | Halo therapy: | Halo (7) | 12 | Transpedical screw (10) | |

| 29 | no or 1–2 mm displacement | |||||||

| Anterior surgery: | ||||||||

| more than 3 mm C2-3 displacement | ||||||||

| Posterior surgery: | ||||||||

| little malposition on lateral film | ||||||||

| while more than 3 mm on CT scan | ||||||||

| Muller et al. [25] | 2000 | 0 | Effendi Type I: 10 | Type I: | Type I: | Type II | Type II | |

| 39 | II: 29 | cervical orthosis | cervical orthosis (10) | flexion subset: | Listhesis subset: (2) | listhesis subset: | ||

| II: | II: flexion subtype | anterior (1) | transpedicle screw (5) | |||||

| stable: conservative treatment | halo (7) hard collar (2) | flexion subset: | ||||||

| unstable: surgery | minerva PoP (1) | transpedicle screw (1) | ||||||

| extension subtype | ||||||||

| hard halo (2) | ||||||||

| listhesis subtype | ||||||||

| halo (8) | ||||||||

| Marton et al. [22] | 2000 | 1 | Effendi Type I: 3 | Halo except one Type I Injury | Effendi Type I: halo (2) | Effendi Type II (1) | ||

| 13 | II: 8 | with great subluxation | II: halo (5) | II (3) | ||||

| III: 2 (1 died) | III: halo (1) | |||||||

| Cosan et al. [8] | 2001 | 0 | Levine and Edwards | Levine and Edwards | Levine and Edwards | Levine and Edwards | Levine and Edwards | |

| 7 | Type I: 3 | Type I: Philadelphia collar | Type I: Philadelphia collar (3) | IIa (1) | III: O-C2 (1) | |||

| II: 2 | II: Philadelphia collar | II: Philadelphia collar (2) | III: anterior (1) | |||||

| IIa: 1 | IIa: surgery | |||||||

| III: 2 | III: Philadelphia collar (1) | |||||||

| halo-vest (1) | ||||||||

| Vieweg et al. [42] | 2001 | 0 | Effendi Type I: 3 | Effendi Type I: stiff neck | Effendi Type I: stiff collar (3) | Effendi Type III (8) | ||

| 17 | II: 6 | II: halo orthosis | II: halo orthosis (6) | |||||

| III: 8 | III: surgery | |||||||

| Moon [24] | 2001–2002 | 0 | Stable: 20 | Stable: halo traction +cervical orthosis | Cervical orthosis (20) | Unstable (16) | Unstable (6) | |

| 42 | Unstable: 22 | Unstable: surgery | (6 plated; 10 nonplated) | (transpedicle screw: 4, wiring: 2) | ||||

| Vaccaro et al. [40] | 2002 | 0 | Levine and Edwards | Type II, IIa: halo | Halo (31) | |||

| 31 | Type II: 27 | |||||||

| IIa: 4 | ||||||||

| Takahashi et al. [35] | 2002 | 0 | Effendi Type III | Reduced | 1 | |||

| 1 |

Classification

In the 1980s, several classification systems were proposed. Since the 1990s, most published articles began to adopt the practical classification proposed by Francis, Effendi, Levine and Edwards. The classification of Effendi et al. modified by Levine and Edwards was applied in 12 papers, whereas the classification of Francis was used only in 2 papers.

Stability

There are several criteria in the literature included in the current study. The definition of stability or instability was listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Criteria of stability or instability in the literature reviewed

| Author | Stability or instability | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Cornish [7] (1968) | Stability | Little in the way of local pain, muscle spasm or referred pain, relatively little movement was shown in the lateral radiographs take in flexion and extension |

| Norrell [26] (1970) | Instability | Dynamic films indicated that the probability of the damage of disc was between C2 and C3 |

| White and Panjabi [43] (1978) | Stability | Less than 3.5 mm anterior displacement of C2 over C3 or less than 11° angulation between C2 and C3 |

| Govender and Charies [14] (1987) | Stability | More than 6 mm anterior displacement and greater than 2 mm movement on flexion/extension radiographs |

| Coric et al. [6] (1996) | Instability | More than 6 mm anterior displacement and greater than 2 mm movement on flexion/extension radiographs |

| Verheggen and Jansen [41] (1998) | Stability of the craniovertebral junction | No transposition on lateral dynamic films, had little Relation to the occurrence of osseous union |

| Marton [22] (2000) | Instability of Type II fractures | The integrity of the disc-ligament entity, and the angulation of dens between 20° and 35° would suggest the tearing of the posterior ligamentous system and the lesion of the posterior part of the disc |

| Moon [24] (2001–2002) | Instability | Abnormal enlargement or rotation of the body and arch of axis combined with a displacement of C2 upon C3 or the full breakage of annular ligament followed with the pedicle injuries |

Management indication

Twenty of 30 (62.5%) publications advocated that the primary therapy for all hangman’s fractures should be conservative. Eleven publications suggested that conservative treatment was suitable to some stable fractures. Only Verheggen and Jansen [41] claimed that surgery might be the primary method to Levine-Edwards Type II, IIa and III fractures.

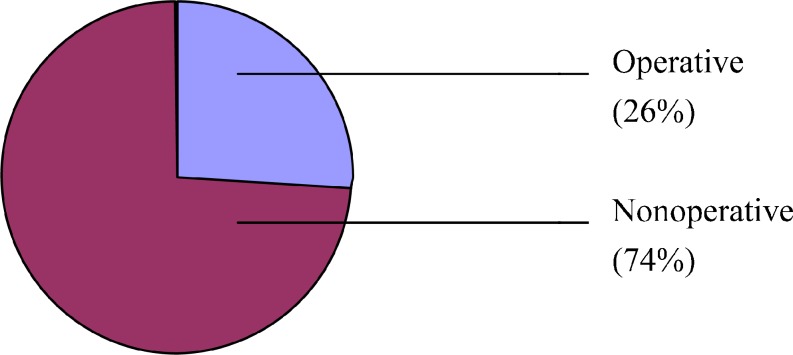

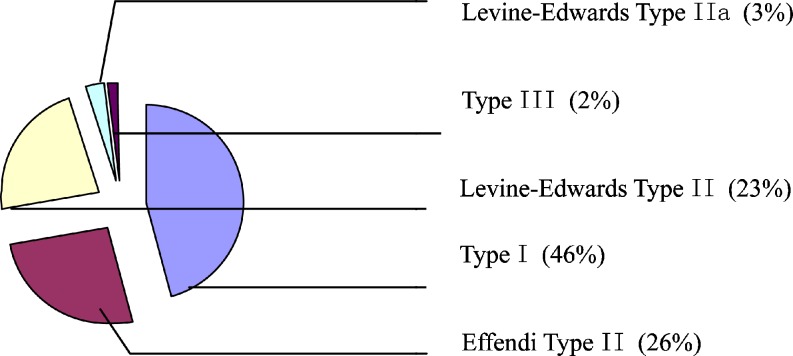

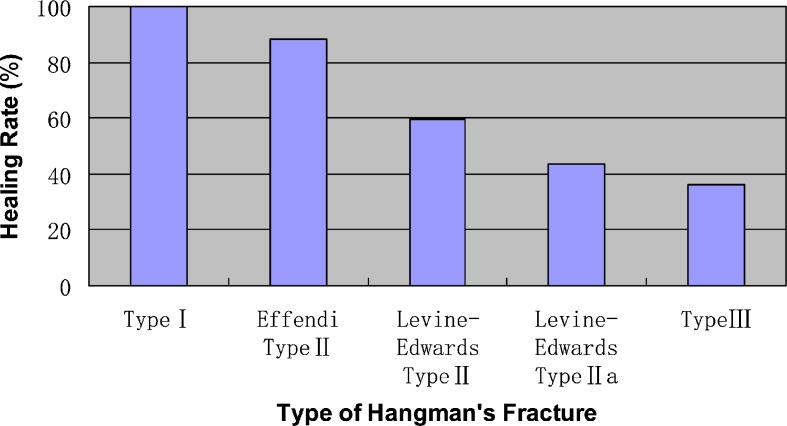

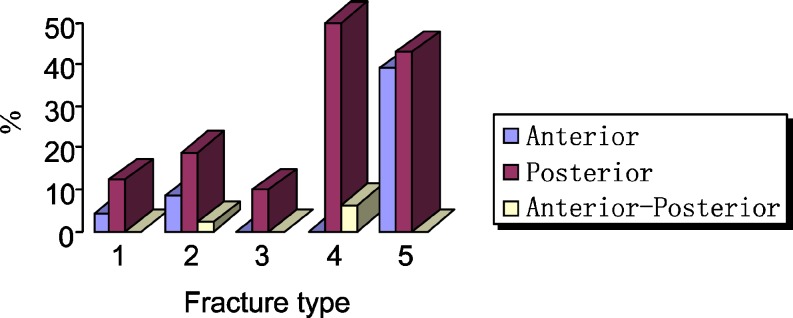

We reviewed and calculated the number of operative and nonoperative patients of each type according to Effendi et al. and Levine and Edwards (Table 5), the proportion of patients treated nonoperatively and operatively was shown in Fig. 3. As shown in Table 5, most patients with Type I, Effendi Type II and Levine-Edwards Type II fractures were treated conservatively, whereas the proportion of nonoperative patients in Levine-Edwards Type IIa and Type III fractures were much smaller (Fig. 4).

Table 5.

Number of patients treated nonoperatively and operatively

| Operative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Total | Nonoperative | Anterior approach | Operative Posterior Approach | Anterior + Posterior approach |

| Type I | 154 | 116 | 6 | 17 | 0 |

| Effendi Type II | 95 | 67 | 8 | 18 | 2 |

| Levine-Edwards Type II | 64 | 58 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Levine-Edwards Type IIa | 16 | 7 | 0 | 8 | 1 |

| Type III | 28 | 5 | 11 | 12 | 0 |

Fig. 3.

Distribution of the nonoperative and operative patients

Fig. 4.

Distribution of fracture type in nonoperative patients

The healing rate of conservative management with regard to fracture type was presented in Fig. 5. The fracture healing was evaluated by radiological appearance in fracture site. The healing rate of patients with conservative treatment decreased sequentially from Type I to III fractures. All Type I fractures treated conservatively achieved successful healing, but the healing rates of both Levine-Edwards Type IIa and III fractures were below 50%.

Fig. 5.

Healing rate of hangman’s fracture in nonoperative patients

Rigid and nonrigid immobilizations were used as the method of conservative treatment in the papers we reviewed. The frequencies of immobilization type were presented in Table 6. All seven case series favoring conservative treatment of Levine-Edwards Type IIa and III fractures used rigid immobilizations alone although different immobilization choices were taken for Type I, Effendi Type II and Levine-Edwards Type II fractures.

Table 6.

Number of publication with regard to different immobilization

| Classification | Rigid alone | Nonrigid alone | Both methods | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | 4 | 3 | 1 | 8 |

| Effendi Type II | 4 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| Levine-Edwards Type II | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Levine-Edwards Type IIa | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Type III | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

As for operative treatment, fusion and stabilization were predominately achieved with use of a posterior approach in patients with all types of hangman’s fractures except Type III fractures (Fig. 6). When Type III fractures were operatively treated, anterior approach was used as often as posterior approach.

Fig. 6.

Distribution of surgical approach in operative patients. 1. Type I; 2. Effendi Type II; 3. Levine-Effendi Type II; 4. Levine-Effendi Type IIa; 5. Type III

Discussion

The viewpoints of management of hangman’s fractures are still controversial. The evidence-based work has not been done yet, which would be highly valuable. From the current study, it was suggested that the classification system proposed by Effendi et al. and modified by Levine and Edwards might be more suitable as a guide for the management of hangman’s fractures.

Conservative treatment

Conservative treatment was usually effective for stable and neurologically normal patients when treated with appropriate immobilization at extended position [38]. The results of this study indicated that surgical intervention is not necessary in most of Type I, Effendi Type II and Levine-Edwards Type II fractures. According to postmortem examination, the fractures are usually located through the superior facet joint, which was full of well vascularized spongy cancellous bone [33]. The narrowing of disc space with osteophytes was often observed in the film of hangman’s fractures for the combined damage to disk and ligaments, and this usually led to spontaneous fusion in severe cases [4]. Clinical practices have identified that it was usual to see the spontaneous union of hangman’s fractures which couldn’t have been influenced by the initial displacement or angulation [3]. Healing in a malunion position with anterior displacement was common and it may be not harmful [5, 13, 20]. According to the analysis of reviewed articles, 20 papers (62.5%) advocated that the primary therapy of all hangman’s fractures should be conservative, and 11 of the rest suggested that conservative treatment was suitable to some stable fractures. Conservative treatment was adopted over 70% in Type I, Effendi Type II and Levine-Edwards Type II fractures, and the healing rate of each type of fracture was 100% in Type I, close to 90% in Effendi Type II and 60% in Levine-Edwards Type II fractures among patients with conservative management. According to our analysis presented in Fig. 5, where conservative treatment was used as the primary therapy of Type I injuries and the healing rate of nonoperative treatment was 100%. This suggests that the indications for conservative treatment of Type I injuries proposed by some authors may be too strict, and conservative management might, in fact, achieve success for all Type I fractures.

As for the methods of conservative treatment, in most of the published articles, tong traction was used in the earliest stage. The fracture could be reduced with tong traction and the stability of the fracture site could be attained after 3–6 weeks traction. Tong traction was safe and comfortable for a long period of time and was especially useful when associated injuries existed. As shown in Table 6, rigid immobilization was strongly recommended in Levine-Edwards Type IIa and III fractures. Nonrigid external fixation was only used in some Type I and Levine-Edwards Type II fractures, often supplemented with rigid immobilization. It is concluded from the results of this study that rigid immobilization might be necessary for most hangman’s fractures. Only in few stable Type I, Effendi Type II and Levine-Edwards Type II fractures, nonrigid immobilization combined with or without rigid immobilization could be an alternative choice when careful inspection is carry out.

Surgery

As far as surgical treatment was concerned, the indications remain debated. In a retrospective series of 131 patients with hangman’s fractures presented by Effendi et al. [11], 42 patients were treated operatively. Francis et al. [13] believed that surgical intervention is needed only for chronic instability secondary to hangman’s fractures. In their series of 123 fractures, only seven patients underwent anterior or posterior fusion. Levine and Edwards [30] suggested that Type-III injuries required surgical stabilization for gross instability.

Patients with Levine-Edwards Type IIa and III fractures should be the candidates. Samaha et al. [30] acclaimed that surgery should be carried out in patients with severe lesions of the mobile segment of C2-C3 with displacement with more than 3 mm of anterior translation and a local kyphosis greater than 15° or a lordosis of more than 5°. As shown in Table 4, more than 50% patients with Levine-Edwards Type IIa and III fractures underwent surgical treatment, we conclude that patients with Levine-Edwards Type IIa and III fractures might be the candidates for surgical stabilization and fusion.

Surgical procedures are divided into anterior, posterior and anterior–posterior approaches. As noted in Table 4, posterior approach was used more frequently than other approaches. In the articles we reviewed, transpedicle screw was used in recently published five papers, whereas wiring and plate were used more widely before. Posterior approach could correct a local kyphosis and prevent flexion deformity. Levine-Edwards Type II, IIa and III fractures were most likely to fail in flexion due to disruption of the C2–3 disc space and the posterior longitudinal ligament and were therefore best treated with posterior stabilization. In Type III fractures, posterior fixation and fusion of the second and third cervical vertebrae were recommended because the only residual stabilizing structure could be reserved [20]. According to Dussault, et al. [10], the Type III lesion must be explored and reduced surgically using a posterior approach, while anterior approach was indicated for those later instability following Type III fractures. Anterior approach can avoid incorporation of the atlas and thus preserve some rotation movement by sparing the atlanto-axial articulation [13]. Taller et al. [36] advocated that an anterior approach was indicated in cases with a C2/C3 dislocation larger than 3 mm initially or on flexion/extension radiographs. Verheggen and Jansen [41] advocated an anterior C2–3 discectomy and fusion in cases with traumatic disk herniation compromising the spinal cord.

From the current study, the healing rate of Type III fractures treated via posterior approach (39.29%) was similar to that via anterior approach (42.86%). So it is suggested both posterior and anterior approach might be indicated for patients with Levine-Edwards Type IIa and Type III fractures.

Limitations of the study

The most appropriate form of the treatment of hangman’s fractures should be decided based upon the statistical evidence. Direct comparisons between management methods of different type of fractures will facilitate the understanding of clinical decision-making. The randomized controlled trials can provide convincible evidence-based conclusions. While it is a drawback that there are not enough reports based on nonrandomized data, it is also true that such studies are not widely available in orthopaedic literature. The standardization for summaries of clinical data in orthopedic surgery should be enhanced as early as possible [40]. Most of the included papers for this systematic review were retrospective studies and only one article was a prospective study [14]. The criteria for evaluating the effect of management were not defined consistently, some articles included only several patients [6, 10, 12, 20, 22, 25, 40], and it is expected that these facts might limit the level of analysis. In the literature included in this study, there was a lack of enough data of Class I medical evidence addressing the issue of treatment of hangman’s fractures. So, it was difficult for us to compare different treatment with each other through clinical spectrum, especially after a long follow-up period. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have a tendency to make system errors, and are easily influenced by other confounding elements [23]. Publication bias was frequently experienced in systematic reviews [9]. If a relevant report was not included, conclusions may be biased. The possibility of missing data might result in system error in the research.

Conclusion

In summary, treatment of the majority of hangman’s fractures achieved a satisfactory outcome with reasonable external immobilization. Treatment options were recommended in regard to the stability of hangman’s fractures. Classification systems especially proposed by Effendi, Levine and Edwards provided guidelines for the treatment of hangman’s fractures. In stable injuries without neurological deficit and signs of later instability, such as Type I, Effendi Type II and Levine-Edwards Type II fractures, it is sufficient to immobilize the cervical spine for a certain period of time. Rigid immobilization alone was necessary for most cases. Surgical stabilization is recommended in unstable cases when there is the possibility of later instability, such as Levine-Edwards Type IIa and III fractures with significant dislocation.

References

- 1.Barros TE, Bohlman HH, Capen DA, Cotler J, Dons K, Biering-Sorensen F, Marchesi DG, Zigler JE. Traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis: analysis of management. Spinal Cord. 1999;37:166–171. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borne GM, Bedou GL, Pinaudeau M. Treatment of pedicular fractures of the axis: a clinical study and screw fixation technique. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:88–93. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.1.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brashear R, Jr, Venters G, Preston ET. Fractures of the neural arch of the axis: a report of twenty-nine cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:879–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bucholz RD, Cheung KC. Halo vest versus spinal fusion for cervical injury: evidence from an outcome study. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:884–892. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.70.6.0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi WG, Vishteh AG, Baskin JJ, Marciano FF, Dickman CA. Completely dislocated hangman’s fracture with a locked C2-3 facet: case report. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:757–760. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.5.0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coric D, Wilson JA, Kelly DL., Jr Treatment of traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis with nonrigid immobilization: a review of 64 cases. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:550–554. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.4.0550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornish BL. Traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1968;50:31–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cosan TE, Tel E, Arslantas A, Vural M, Guner AI. Indications of Philadelphia collar in the treatment of upper cervical injuries. Eur J Emerg Med. 2001;8:33–37. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200103000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniels CE, Montori VM, Dupras DM. Effect of publication bias on retrieval bias. Acad Med. 2002;77:266. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200203000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dussault RG, Effendi B, Roy D, Cornish B, Laurin CA. Locked facets with fracture of the neural arch of the axis. Spine. 1983;8:365–367. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198305000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Effendi B, Roy D, Cornish B, Dussault RG, Laurin CA. Fractures of the ring of the axis: a classification based on the analysis of 131 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63:319–327. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.63B3.7263741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francis WR, Fielding JW. Traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1978;9:1011–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francis WR, Fielding JW, Hawkins RJ, Pepin J, Hensinger R. Traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63:313–318. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.63B3.7263740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Govender S, Charles RW. Traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis. Injury. 1987;18:333–335. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(87)90055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greene KA, Dickman CA, Marciano FF, Drabier JB, Hadley MN, Sonntag VKH. Acute axis fractures: analysis of management and outcome in 340 consecutive cases. Spine. 1997;22:1843–1852. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199708150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadley MN, Browner C, Sonntag VK. Axis fractures: a comprehensive review of management and treatment in 107 cases. Neurosurgery. 1985;17:281–290. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198508000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadley MN, Dickman CA, Browner CM, Sonntag VK. Acute axis fractures: a review of 229 cases. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:642–647. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.71.5.0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johner R, Wruhs O. Classification of tibial shaft fractures and correlation with results after rigid internal fixation. Clin Orthop. 1983;178:7–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levine AM. Traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis: hangman’s fracture. In: Clark CR, Ducker TB, Dvorak J, Garfin SF, Herkowitz HN, Levine AM, Pizzutillo PD, Ullrich CG, Zeidman SM, editors. The cervical spine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. pp. 429–448. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine AM, Edwards CC. The management of traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:217–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine AM, Rhyne AL. Traumatic spondilolisthesis of the axis. Semin Spine Surg. 1991;3:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marton E, Billeci D, Carteri A. Therapeutic indications in upper cervical spine instability: considerations on 58 cases. J Neurosurg Sci. 2000;44:192–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montori VM, Swiontkowski MF, Cook DJ. Methodologic issues in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Clin Orthop. 2003;413:43–54. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000079322.41006.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moon MS, Moon JL, Moon YW, Sun DH, Choi WT. Traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis: 42 cases. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2001;60:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller EJ, Wick M, Muhr G. Traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis: treatment rationale based on the stability of the different fracture types. Eur Spine J. 2000;9:123–128. doi: 10.1007/s005860050222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norrell H, Wilson CB. Early anterior fusion for injuries of the cervical portion of the spine. JAMA. 1970;19(214):525–530. doi: 10.1001/jama.214.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pepin JW, Hawkins RJ. Traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis: hangman’s fracture. Clin Orthop. 1981;157:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, Ford SE. Halo immobilization and surgical fusion: relative indications and effectiveness in the treatment of 140 cervical spine injuries. J Trauma. 1990;30:893–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roda JM, Castro A, Blazquez MG. Hangman’s fracture with complete dislocation of C-2 on C-3: case report. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:633–635. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.3.0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samaha C, Lazennec JY, Laporte C, Saillant G. Hangman’s fracture: the relationship between asymmetry and instability. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:1046–1052. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.82B7.10408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider RC, Livingston KE, Cave AJ, Hamilton G. “Hangman’s fracture” of the cervical spine. J Neurosurg. 1965;22:141–154. doi: 10.3171/jns.1965.22.2.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seljeskog EL, Chou SN. Spectrum of the hangman’s fracture. J Neurosurg. 1976;45:3–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.1976.45.1.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherk HH, Howard T. Clinical and pathologic correlations in traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis. Clin Orthop. 1983;174:122–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Starr JK, Eismont FJ. Atypical hangman’s fractures. Spine. 1993;18:1954–1957. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199310001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahashi T, Tominaga T, Ezura M, Sato K, Yoshimoto T. Intraoperative angiography to prevent vertebral artery injury during reduction of a dislocated hangman fracture: case report. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(Spine 3):355–358. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.97.3.0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taller S, Suchomel P, Lukas R, Beran J. CT-guided internal fixation of a hangman’s fracture. Eur Spine J. 2000;9:393–397. doi: 10.1007/s005860000159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan ES, Balachandran N. Hangman’s fracture in Singapore (1975–1988) Paraplegia. 1992;30:160–164. doi: 10.1038/sc.1992.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Termansen NB. Hangman’s fracture. Acta Orthop Scand. 1974;5:529–539. doi: 10.3109/17453677408989176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tuite GF, Papadopoulos SM, Sonntag VK. Caspar plate fixation for the treatment of complex hangman’s fractures. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:761–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaccaro AR, Madigan L, Bauerle WB, Blescia A, Cotler JM. Early halo immobilization of displaced traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis. Spine. 2002;27:2229–2233. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200210150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verheggen R, Jansen J. Hangman’s fracture: arguments in favor of surgical therapy for type II and III according to Edwards and Levine. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:253–262. doi: 10.1016/S0090-3019(97)00300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vieweg U, Schultheiss R. A review of halo vest treatment of upper cervical spine injuries. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121:50–55. doi: 10.1007/s004020000182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White AA, Panjabi MM. Clinical biomechanics of the spine. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams TG. Hangman’s fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1975;57:82–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]