Abstract

The odontoid process of C2 projects upward from the superior roof of the body of C2. There is a confusion about the inferior border of the odontoid. The aims of this clinical study were to describe the inferior border of the odontoid process based on the remnant of dentocentral synchondrosis in adults, and the estimation of the odontoid/body ratio in pediatric and adult ages. Sixty-six cases were included for this study. Forty-four of them were in adult ages and the remaining 22 of them were in pediatric ages. The region of occiput, C1, C2, and C3, was examined with the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in all cases. The length of the odontoid process was estimated by using radiological images of MR from the tip of the odontoid to the remnant of dentocentral synchondrosis. The portion located under the level of synchondrosis was considered as the body of C2. The average length of the odontoid was 18. 6 mm in pediatric and 21. 3 mm in adult cases. In adult females, the length of the odontoid process (19. 1 mm in length) was smaller than those of adult males (23. 6 mm in length). The average ratio of odontoid/body was two in pediatric and 1.8 in adult cases. This study demonstrated that the neck of the odontoid segment at the level of superior articulating facets is not the synchondrosis between the odontoid process and the body of C2. The synchondrosis is located well below the level of superior articulating facets. It can be demonstrated with sagittal and coronal images of MR in both of pediatric and adult individuals.

Keywords: Axis, Dentocentral synchonrosis, Odontoid process, inferior border of the odontoid process

Introduction

The upper cervical spine consists of the foramen magnum, paired occipital condyles, C1, and C2 [2, 9]. This segment serves as a transitional zone between the rigid calvarium and flexible lover cervical spine [2, 9]. C2 is the largest structure with its unique shape and function in this segment [9]. It consists of a body, paired pedicles, lateral masses (superior articulating facets, pars interarticularis, and inferior articulating facets), laminae, and bifid spinous process [2, 9].

The odontoid process of C2 projects upward from the superior roof of the body, and makes it different from the others [2, 9]. In embryological developmental stages, C2 forms from four bones separated by synchondrotical articulations and consisting of four ossifications centers (two of them are located in the neural arches bilaterally, one of them is located in the body, and one is located in the odontoid process). The borders of the odontoid process are well demarcated by these cartilaginous articulations during prenatal and postnatal development of C2 until the ending of ossification process. These cartilaginous articulations are named as dentocentral (separating odontoid from the body), and neurocentral synchondrosis (separating odontoid and body from neural arches) [4]. Synchondroses among the neural arches, body, and odontoid process fuse at 3–6 years of ages. After the ages of 6 years, odontoid process fuses with the body and the neural arches. In adult age, the remnant of the dentocentral synchondrosis can be imagined by magnetic resonance images (MRI) as a hypointense ring between the inferior end of the odontoid and the superior roof of the body of C2. This structure is located in the cancellous bone, and should be accepted as the inferior border of the odontoid process in adults. The anatomical level of dentocentral synchondrosis is well below from the superior articulating facets and the indentation of the transverse ligament to the posterior aspect of the odontoid process.

The aims of this study were to demonstrate of the remnant of the dentocentral synchondrosis in adults by using sagittal and coronal MR images, to describe the inferior border of the odontoid process based on the level of this remnant of synchondrosis, and to estimate the length of the odontoid and the body of C2 with the calculation of the odontoid/body ratio. This study, furthermore, may help to reveluate the localization of Type III odontoid fracture of Anderson and D’Alanzo.

Materials and methods

Study population consists of 44 adults (29 males aged between 18 years and 71 years, and 15 females aged between 32 years and 60 years), and 22 pediatric cases (11 males aged between 3 years and 17 years, and 11 females aged between 3 years and 13 years). Upper cervical spine of all patients was examined by using MRI. The images were not obtained as part of a research protocol, but all cases underwent cervical MRI examination because of the necessity of other causes.

Magnetic resonance images were obtained using a 1.0-tesla unit (General Electric) with a neck and/or head surface coil. The MR imaging protocol for upper cervical region included 3-mm sagittal T1-weighted (TR 600 msec, TE 20 msec) and T2-weighted turbo spin-echo (TR 2500 ms, TE 80 ms) sequences.

Lateral and anterior odontoid radiographs were obtained in all patients (Fig. 1c). Six patients also underwent Oc-C2 computerized scanning with sagittal reconstructions (Fig. 2c). Coronal MR Images were obtained in ten of the patients. Midsagittal and midcoronal MR images were scanned and converted into digital images by using 3.2 megapixel digital photo machine (Sony, Japan). All digital images were copied into a hard-disc of a computer (Vestel Asteo computer, Turkey). The images were opened with a software program of the photo analyzing (Adobe photoshop elements 2.0). Images of the upper cervical region were magnified into original sizes based on the MR scale (this scale is showing us the minimification degree of a film) imprinted on the all MR windows of the films.

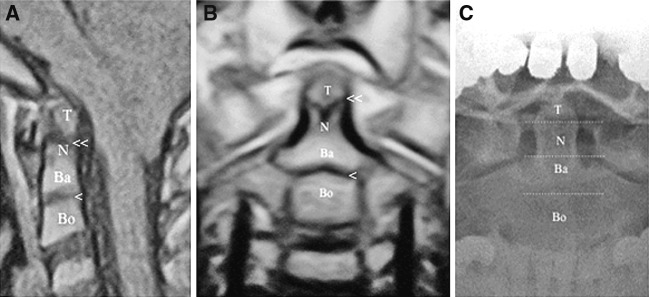

Fig. 1.

a Sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in a 3 years old pediatric individual shows the tip, neck, and base of the odontoid process (T tip of the odontoid, N the neck of the odontoid, Ba the base of the odontoid, Bo the body of C2, one arrow shows dentocentral synchondrosis, double arrow shows apicodental synchondrosis). b. Coronal T1-weighted MRI of a pediatric case shows the segments of the odontoid process (T tip of the odontoid, N the neck of the odontoid, Ba the base of the odontoid, Bo the body of C2, one arrow shows dentocentral synchondrosis, double arrow shows apicodental synchondrosis). c Segmentation of an adult odontoid process in a direct X-ray (T tip of the odontoid, N the neck of the odontoid, Ba the base of the odontoid, Bo the body of C2)

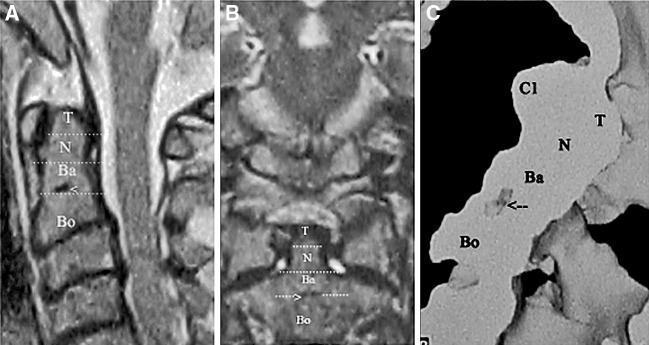

Fig. 2.

a Sagittal T1-weighted MRI in a 63 years old adult individual shows the tip, neck, and base of the odontoid process (T tip of the odontoid, N the neck of the odontoid, Ba the base of the odontoid, Bo the body of C2, arrow shows the remnant of the dentocentral synchondrosis). b Coronal T1-weighted MRI of an adult case shows the segments of the odontoid process (T tip of the odontoid, N the neck of the odontoid, Ba the base of the odontoid, Bo the body of C2, arrow shows the remnant of the dentocentral synchondrosis). c 3D reconstruction of C2 in the adult case shows the remnant of the dentocentral synchondrosis (T tip of the odontoid, N the neck of the odontoid, Ba the base of the odontoid, Bo the body of C2, arrow shows the remnant of the dentocentral synchondrosis)

The length of the odontoid process from its tip to the remnant of dentocentral synchondrosis was estimated with the estimating tool of this software program. With the same way, the length of the body from the remnant of dentocentral synchondrosis to inferior border of C2 was estimated and recorded. Chi-square test was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Sixty-six pediatric and adult cases (40 male and 26 female, aged between 3 years and 71 years) were included for this study. Twenty-two cases were in the ages and eight of them and/or six were under the ages of this year. Dentocentral synchondrosis in the pediatric age and its remnant in adult ages were demonstrated in all cases by using sagittal images of MR (Figs. 1, 2).

In the pediatric age group, the average length of odontoid was estimated as 18. 6±1. 5 mm in male and 18. 5±1. 6 mm in female. The body length was estimated as 9. 7±2.1 in male and 9. 3±0. 9 in female. The odontoid/body ratio was estimated as two in both groups. There were no statistical differences between the male and the female cases in pediatric age group.

In adults, the average length of the odontoid process was estimated as 23. 6±1. 2 mm in male and 19. 1±1. 2 mm in female. The body length was found as 12. 5±1. 2 mm in male and 11. 2±1. 2 mm in female. The odontoid/body ratios were found as 1. 8 in male and 1. 7 in female. The results were shown in Table 1. The difference of odontoid and body length between males and females was statistically significant in adult group.

Table 1.

The length of the odontoid, body and the Odontoid/body ratio in the pediatric and adult ages

| Groups | Odontoid (mm) | Body (mm) | Odontoid/body ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric female | 18. 5±1. 6 | 9. 3±0. 9 | 2 |

| Pediatric male | 18. 6±1. 5 | 9. 3±2. 1 | 2 |

| Adult female | 19. 1±1. 2 | 11. 2±1. 2 | 1. 7 |

| Adult male | 23. 6±1. 2 | 12. 5±1. 2 | 1. 8 |

Discussion

This clinical study demonstrated that the remnant of the dentocentral synchondrosis was located well below the superior articulating facets and can be imagined by sagittal and coronal images of magnetic resonance. This remnant can be seen in pediatric, adult, and even in the elderly ages. The localization and level of the remnant of the dentocentral synchondrosis is not only important as an anatomical detail but also it is extremely important in the aspect of clinical perspective because of the odontoid and C2 fractures. According to the localization of the dentocentral synchondrosis, the odontoid segment may be divided into three segments. The first segment is the tip of odontoid. This segment is separated from the second segment of odontoid (the neck) by the apicodental synchondrosis. The neck of odontoid process lies between the apicodental synchondrosis and the level of the superior articulating facets. The third segment connects the neck to the body of C2 via the dentocentral synchondrosis, and can be named as the base of odontoid segment. This segment also fuses with the neural arches bilaterally.

Stillerman et al. [9], in their chapter in the classical monograph of Neurosurgery, defined the line at the level of the superior articulating facets as the synchondrosis and stated that the majority of odontoid fractures involve this line where the odontoid process fuses with the body of C2. In fact, this line is just the border between the neck and the base of the odontoid segment, and the real dentocentral synchondrosis is located between the base of the odontoid and the body of C2, and more below from the neck of the odontoid.

Benzel et al. [1], described Type III odontoid process fractures of Anderson and D’Alanzo as the horizontal fractures of C2 body. According to our study, Type III odontoid fractures should be classified into the group of the odontoid fractures. Because inferior border of the odontoid ends at the level of the dentocentral synchondrosis. This level is well below the superior articulating facets as presented here.

The external surface anatomy of C2 studied and well described previously in many anatomical studies [2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 10]. But the internal anatomy of the vertebral bones, especially internal trabecular anatomy of C2 was studied by a few published articles in the aspect of biomechanical properties and the segmental anatomy [5]. Like the external anatomy, the internal anatomy and segmentation of C2 is unique among the other cervical vertebraes (Figs. 3 and 4). Heggeness et al. [5], had been studied the internal anatomy of C2 in cadaveric bones with coronally and sagittally sliced specimens by using bone saw. They described the relevance of cortical bone thickness, the prominences of its surface, and the internal trabeculation of cancellous bone with its force transmission characteristics as well as the biomechanical properties [5].

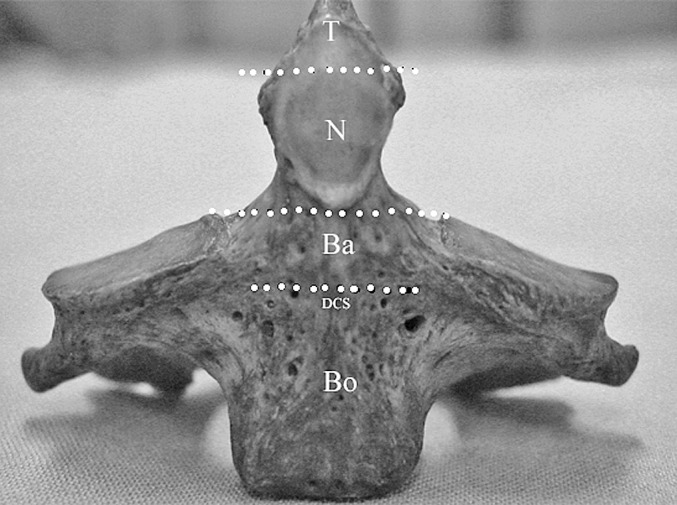

Fig. 3.

The segments of C2 were marked in a cadaveric bone (T tip of the odontoid, N the neck of the odontoid, Ba the base of the odontoid, Bo the body of C2, DCS dentocentral synchondrosis)

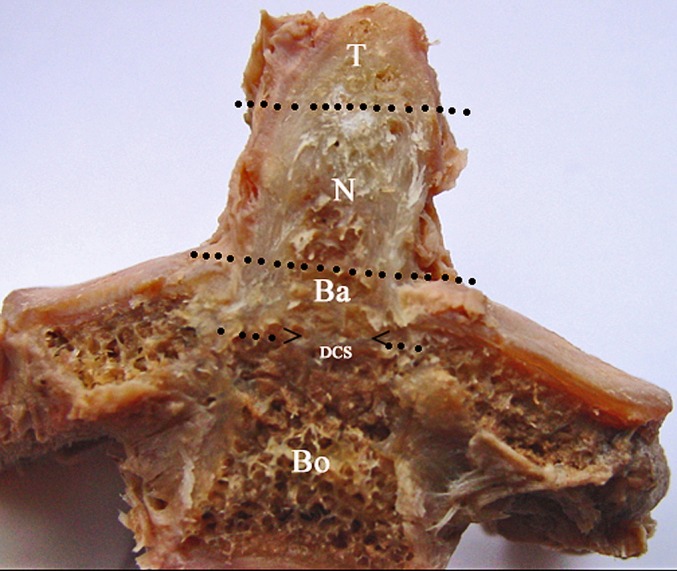

Fig. 4.

The location of dentocentral synchondrosis was shown in a cadaveric bone (T tip of the odontoid, N the neck of the odontoid, Ba the base of the odontoid, Bo the body of C2, DCS dentocentral synchondrosis, arrows show the remnant of the dentocentral synchondrosis)

MRI is a useful neuroradiological diagnostic tool in the investigation of the internal cancellous anatomy of the vertebral bones in the living subjects with different ages. Our study revealed that MRI has a high capability in the demonstrating of the remnant of dentocentral synchondrosis in both of coronal and sagittal images. CT with bone window can show the cortical bone structure in the odontoid and body segments. But it is difficult to distinguish the remnant of neurocentral synchondrotic articulations; the remnant of dentocentral synchondrosis was seen as a hypointense disc in T1-weighted images located midline between the space of odontoid and the body of C2. In T2-weighted MR images, this area was seen as a hypointense area.

This study demonstrated that the length of the odontoid process and the body of C2 in adult cases is longer than those of the pediatric cases. The difference between these two groups was statistically significant. The ratio of the lengths of the odontoid and the body was two in pediatric group and 1. 8 in adult group. This ratio was slightly higher in pediatric cases than those of adults. There were no significant differences between pediatric males and pediatric females in the aspect of the length of the odontoid and the body. But in adult group, the length of the odontoid and the body were longer in male adults than those of female adults. The difference was statistically significant.

The author’s innovative points of view in this clinical study were to demonstrate the location of the remnant of the dentocentral synchondrosis between the base of the odontoid and the body of C2, to show the location of this point is well below the level of the superior articulating facets in adult and in the pediatric individuals as seen in the images of sagittal and coronal MR, the description of the inferior border of the odontoid process using this remnant of synchondrosis, and the estimation of the lengths of the odontoid and the body of C2 as well as the estimation of the odontoid/body ratio.

Conclusion

Based on the localization of the dentocentral synchondrosis, the odontoid process of C2 may be divided into three segments as mentioned above; the tip, the neck, and the base. The base of the odontoid process begins from the level of superior articulating facets, and ends at the level of the remnant of the dentocentral synchondrosis. The level of superior articulating facets should be considered as a border inside the odontoid process separating the neck from the base of the odontoid segments.

References

- 1.Benzel EC, Hart BL, Ball PA, Baldwin NG, Orrison WW, Espinosa M. Fractures of the C-2 vertebral body. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:206–212. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.2.0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doherty BJ, Heggeness MH. Quantitative anatomy of the second cervical vertebra. Spine. 1995;20:513–517. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199503010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebraheim NA, Fow J, Xu R, Yeasting RA. The location of the pedicle and pars interarticularis in the axis. Spine. 2001;26:34–37. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200102150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garton HJL, Park P, Papadopoulos SM. Fracture dislocation of the neurocentral syncondroses of the axis. Case illustration. J Neurosurg Spine. 2002;96:350. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.96.3.0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heggeness MH, Doherty BJ. The trabecular anatomy of the axis. Spine. 1993;14:1945–1949. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199310001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koebke J. Morfological and functional studies on the odontoid process of the human axis. Anat Ebryol (Berl) 1979;155:197–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00305752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandel IM, Kambach BJ, Petersilge CA, Johnstone B, Yoo JU. Morphologic consideration of C2 isthmus dimentions for the placement of transarticular screws. Spine. 2000;25:1542–1547. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200006150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaffler MB, Alson MD, Heller JG, Garfin SR. Morfology of the dens. A quantitative study. Spine. 1992;17:738–743. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stillerman CB, Roy RS, Weiss MH. Cervical spine injuries: diagnosis and management. In: Wilkins RH, Rengachary SS, editors. Neurosurgery. 2nd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996. pp. 2875–2904. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu R, Burgar A, Ebraheim NA, Yeasting RA. The quantitative anatomy of the laminas of the spine. Spine. 1999;15:107–113. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199901150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]