Abstract

Description of a workshop entitled “Sharing Guidelines for Low Back Pain Between Primary Health Care Providers: Toward a Common Message in Primary Care” that was held at the Fifth International Forum on Low Back Pain in Primary Care in Canada in May 2002. Despite a considerable degree of acceptance of current evidence-based guidelines, in practice, primary health care providers still do not share a common message. The objective of the workshop was to describe the outcomes of a workshop on the sharing of guidelines in primary care. The Fifth International Forum on Low Back Pain Research in Primary Care focused on relations between stakeholders in the primary care management of back pain. Participants in this workshop contributed to an open discussion on “how and why” evidence-based guidelines about back pain do or do not work in practice. Ways to minimise the factors that inhibit implementation were discussed in the light of whether guidelines are mono-disciplinary or multidisciplinary. Examples of potential issues for debate were contained in introductory presentations. The prospects for improving implementation and reducing barriers, and the priorities for future research, were then considered by an international group of researchers. This paper summarises the conclusions of three researcher subgroups that focused on the sharing of guidelines under the headings of: (1) the content, (2) the development process, and (3) implementation. How to share the evidence and make it meaningful to practice stakeholders is the main challenge of guideline implementation. There is a need to consider the balance between the strength of evidence in multidisciplinary guidelines and the utility/feasibility of mono-disciplinary guidelines. The usefulness of both mono-disciplinary and multidisciplinary guidelines was agreed on. However, in order to achieve consistent messages, mono-disciplinary guidelines should have a multidisciplinary parent. In other words, guidelines should be developed and monitored by a multidisciplinary team, but may be transferred to practice by mono-disciplinary messengers. Despite general agreement that multi-faceted interventions are most effective for implementing guidelines, the feasibility of doing this in busy clinical settings is questioned. Research is needed from local implementation pilots and quality monitoring studies to understand how to develop and deliver the contextual understanding required. This relates to processes of care as well as outcomes, and to social factors and policymaking as well as health care interventions. We commend these considerations to all who are interested in the challenges of achieving better-integrated, evidence-based care for people with back pain.

Keywords: Back pain, Guidelines, Primary Care, Implementation

Introduction

The implementation of national guidelines has become an established principle of health care, especially when these address areas of priority, high social impact or cost [8]. Low back pain is one such high-cost condition [4]. However, implementing back pain guidelines appears to be at least as problematical as for any other health area [2, 3, 10, 11, 13, 20, 22–24], leaving a considerable gap between ‘the best practice’ and ‘usual practice’ in primary care.

It has been suggested that effective implementation operates in the same way as effective professional development, which is in a conclusive environment that promotes positive attitudes towards improving care. This should provide both the resources and time to accommodate change [16]. In practice, however, this environment can be more difficult to achieve where there are multiple stakeholders and multiple care providers. The difference in their perspectives, if not reconciled, can eliminate the benefits of evidence-based practice for patients. One important factor in doing this is thought to be the status of the guideline itself and its quality. The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE) Instrument [1], for example, provides an assessment framework for this under six quality headings. Agreed quality, however, may not necessarily be followed by acceptance and use. This may have other, more discipline-specific barriers.

The Fourth International Forum on Low Back Pain Research in Primary Care, held in Eilat, Israel in March 2000, suggested ways to narrow the gap between research results and actual practice [25]. These recommendations have considerable resonance with the literature on guideline implementation. However, so ubiquitous is back pain that many stakeholders can influence the uptake of guidelines by their acceptance or otherwise and this will be dependent on their perspectives and priorities. For example, in general practice, implementation methods have been found more likely to be effective when they operate directly on the consultation between the professional and the patient [8]. Such methods include restructuring medical records, using patient specific reminders at consultation, patient-specific feedback through an audit system and incentives in the form of gifts or credits [5, 6, 14]. Other reported important factors influencing implementation by general practitioners are clarity, absence of bias and resonance with usual practice [9, 26]. However, many general practice care decisions appear to be related to issues not differentiated in guidelines [22], a feature which is apparently in common with the physical therapy professions [7].

The Fifth International Forum on Low Back Pain Research in Primary Care, in Montreal in May 2002, addressed the reasons why evidence does not enter practice in the context of relations between stakeholders and under the theme, “How Many Does it Take to Tango?”. This included a discussion of leading researchers on “The Transfer of Research Results for Decision Making” and involved a wide range of stakeholders from patients to policymakers. The present paper reports on the findings of a workshop of primary care researchers entitled: “Interdisciplinarity in Primary Care”, which was central to the themes of the Forum and explored the pros and cons of tailoring guidelines to individual disciplines (Table 1). Its content is targeted at those involved in the development, dissemination, adaptation, implementation or use of back pain guidelines, as well as to those wishing to conduct research into the obstacles and opportunities for achieving integrated, evidence-based care.

Table 1.

Specific aims of the workshop

| Identify advantages and disadvantages of mono-disciplinary and multidisciplinary guidelines |

| Formulate recommendations regarding when mono-disciplinary and when multidisciplinary guidelines should be developed |

| Identify priorities for future research in this area |

Methods

The workshops took place over 2 days. The group was multinational (Canada, Denmark, Netherlands, Sweden, UK and US) and multidisciplinary (chiropractic, general practice, osteopathy, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, psychology, public health research and rheumatology). All were active researchers. Participants were asked to respond to statements about whether primary care providers could, or should, share the same guidelines. Three presentations were given under the headings of: (1) “The content of guidelines”, (2) “Guideline development”, and (3) “Implementation”. Three subgroups of five to eight participants each met to debate these topics, initially by responding to several pre-prepared statements which were designed to stimulate discussion (but did not represent the opinions of the presenters) (Table 2). The group then focussed on the aims of the workshop (Table 1). Subgroup chairmen summarised their findings on flip charts and presented them to the combined group. The workshop chairman then summarised the findings at a subsequent plenary session of the Forum.

Table 2.

Workshop subgroups’ assigned considerations

| Subgroup A—content of guidelines: |

| Mono-disciplinary guidelines are more detailed than multidisciplinary guidelines |

| Mono-disciplinary guidelines are more innovative than multidisciplinary guidelines |

| Multidisciplinary guidelines are a tower of Babel |

| Multidisciplinary guidelines are more likely to deviate from ‘the norm’ or from ‘routine care’ of separate health care professions |

| Mono-disciplinary guidelines reflect the interests of the discipline concerned even if they are evidence-based |

| Subgroup B—process of guidelines development: |

| Multidisciplinary peer-review of mono-disciplinary guidelines is the best option |

| Multidisciplinary guidelines should be the ‘gold standard’ from which mono-disciplinary guidelines may derive |

| Mono-disciplinary guidelines should always precede multidisciplinary guidelines |

| Subgroup C—implementation of guidelines: |

| Multidisciplinary guidelines are more widely supported |

| Multidisciplinary guidelines are the only way to stop the overload of guidelines |

| Multidisciplinary guidelines stand a greater chance of unifying practice |

| The implementation of multidisciplinary guidelines required additional contextual explanation |

| The multi-faceted interventions required to get multidisciplinary guidelines implemented are too onerous |

Results

Content

There was strong agreement that back pain guidelines should be evidence-based. Mono-disciplinary guidelines were thought to be more likely to be consensus-based as well as biased—especially in areas where evidence is weak and discipline self-interest is strong (Table 3). However, there have been calls for mono-disciplinary guidelines from within professions. The evidence should, therefore, be as strong as possible in order to avoid the need for frequent amendments.

Table 3.

Summary of workshop results: mono-disciplinary or multidisciplinary guidelines?

| Content |

| Mono-disciplinary guidelines are more likely to be biased if evidence is weak |

| Mono-disciplinary guidelines should have a multidisciplinary parent |

| Consistent messages between mono-disciplinary guidelines are essential |

| Development |

| The type of guideline is mainly determined by the feasibility of multidisciplinary recommendations for individual groups |

| Parent guideline development should involve all relevant stakeholders |

| Offspring mono-disciplinary guidelines need to be subjected to multidisciplinary peer-review |

| Development should focus on lines of behaviour and interventions and not access to care |

| Implementation |

| The influence of commercial interests on clinical practice needs to be acknowledged |

| Implementation should include public education and practitioner guidance |

| Mono-disciplinary guidelines are easier to implement, while multidisciplinary guidelines have a greater chance of unifying practice |

| Resources should be available for providing contextual information for multidisciplinary guidelines |

| Implementation strategies should target public policymakers at least as much as providers and (preferably) include national messages |

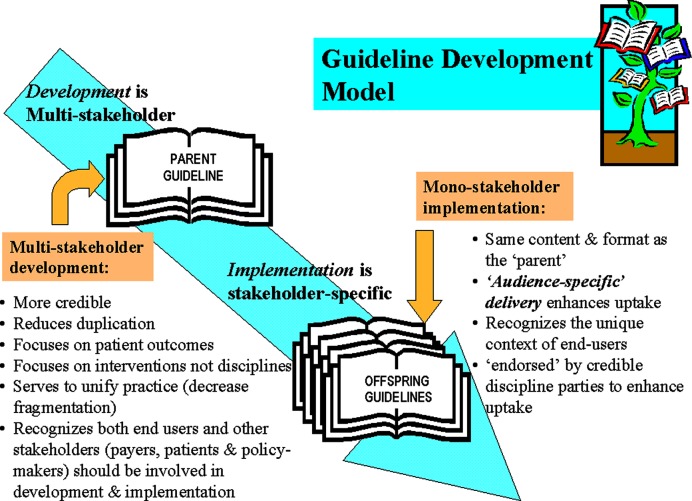

Multidisciplinary guidelines generally contain recommendations linked to strong evidence, rather than from the interests and perspectives of intended users where there may be little or no evidence upon which to base guidance. In order to achieve consistent messages, therefore, mono-disciplinary guidelines should have a multidisciplinary parent and be developed, and monitored, by a multidisciplinary team. The actual transfer of guidelines to practice can be overseen by discipline-specific messengers which might facilitate uptake. Mono-disciplinary guidelines should be fashioned in the same language and format as the multidisciplinary parent guideline (i.e. refer to the same patient outcomes, evidence and interventions). However, they should not be over-structured or over-standardised. They will inevitably contain recommendations about interventions that do not apply to all care providers. Even though the content is audience-specific, the message carried by each mono-disciplinary guideline should be consistent with every other. This enhances the consensus about which roles are shared and which are exclusive, breaks down “silos”, builds cross-disciplinary collaboration and avoids potentially confusing multiple messages to carers.

Guidelines development

Some kind of formulation is needed of the preferred circumstances and prerequisites for choosing to develop either mono-disciplinary or multidisciplinary guidelines. Close to the core of this issue is the feasibility of the recommendation for its recipient, whose practice behaviour may be strongly influenced from within a professional group. It can be argued that disciplines that have low interest in a multidisciplinary perspective may be better served by a mono-disciplinary guideline. However, there is poor agreement between guideline developers about the relevance of behaviour change by patients and care providers, as opposed to the evidence itself.

Multidisciplinary guidelines may reduce the guidelines overload and by their very nature achieve wider support. They may also be a basis for mono-disciplinary offsprings. If so, the parent guideline development should involve all relevant stakeholders (providers, consumers, payers, policy makers) in a multidisciplinary team. However, the offspring mono-disciplinary guideline still needs to be subjected to multidisciplinary peer-review, by a team carefully chosen in order to retain the balance between evidence and professional relevance. Guidelines should give advice about behaviour and interventions, and recommendations about access to care should not be included (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Guideline development model

Implementation

Primary care back pain guidelines are meant to help clinicians in caring for patients in the wider context of health (the biopsychosocial model), without neglecting the need to adequately investigate underlying disease where necessary. However, implementation seems full of uncertainty. Disseminating a guideline may be dependent on the politics of the day and the implementation of evidence-based recommendations can be overridden by, for example, reimbursement systems. The influence of commercial interests on clinical practice needs to be acknowledged. Implementation can also be seriously influenced by the workloads of the practitioners, therefore, adequate efforts also need to go to education of the public at large. However, the main challenge of guideline implementation is how to share the evidence in the first place and make it meaningful to stakeholders.

A good mono-disciplinary guideline will be easier to implement, but multidisciplinary guidelines were felt to have a greater chance of unifying practice (especially for general practice and professions allied to medicine). If successfully implemented, these should help reduce fragmentation in care by achieving consistency across professions and delivering common messages. However, there is a danger that they can be seen as being directed at general practitioners and of lesser relevance to other professionals. Multidisciplinary guidelines need more contextual information than mono-disciplinary guidelines to avoid this. Inevitably this requires more effort and resources.

The most widely accepted implementation strategies centre around multi-faceted initiatives, targeting different barriers [18]. However, this can be prohibitively expensive. It is also important to target policymakers as well as care providers. Competing initiatives and priorities have been implicated in failed implementation resulting in wasted effort and missed opportunities [12]. National messages are needed to have best effect and should have multidisciplinary emphases. Whether multidisciplinary or mono-disciplinary, where there is consensus about a guideline it should be easier to implement. Funding for implementation interventions was also a major concern. The lack of governmental funding and the lack of time for the different professions to actually read the guideline and take part in different interventions to facilitate guideline use were also identified as barriers. These issues have to be solved in order to achieve successful implementation.

Research agenda

Future research in the implementation of primary care back pain guidance should prioritise: (1) the piloting of implementation strategies at local levels, (2) barriers to guideline implementation, and (3) the process and clinical outcomes of implementation. This would include the understanding, beliefs and attitudes of stakeholders, including policymakers. For carers, it could be aimed at explaining clinical behaviour and allow the generation and piloting of cost-effective implementation strategies. Outcomes of these strategies should be carefully monitored for their effects on both the process and the clinical outcomes for patient care.

The piloting of implementation strategies at local levels

There is little research to inform the contextual information needed to assist in the implementation of multidisciplinary guidelines. How and when to deliver this contextual information and where to target the resources are questions still outstanding. Small local pilots of the implementation of national guidance should give clues to this, and could helpfully inform national strategies. Despite the evidence for multi-faceted interventions [17], the resources and/or the political will for them are often lacking. Such pilots would seek to draw on the experience of the few who have attempted to develop and deliver such contextual information and increase the number of individuals with this experience.

It should be possible to monitor the results of implementation strategies that include carefully formulated, contextual information. The response of stakeholders to this, as well as the process and outcome of care, would then need to be taken into account. Successful guideline implementation at local levels might therefore be a two-stage process. By first identifying where context can be tailored to produce a shared understanding and resources targeted to action it, it might be possible to produce better implementation and, consequently, better outcomes for patients.

Investigation of barriers to implementation

There is some published evidence about what the barriers are to back pain recommendations in general practice [3, 12, 15, 22, 23], and even less for other disciplines. These perceptions may have much in common with other clinical areas, where there is research to inform the questions to ask [19]. Reasons for reluctance to change practice behaviour are thought to include financial disincentives but, as yet, there is little evidence to confirm this. For some, lack of access to the treatments recommended may be a strong disincentive, and outcomes research linked to interventions in patient subgroups is a large area awaiting clarification. Documentation is needed of patient care experiences in order to allow anticipation of the types of barriers and opportunities that can arise.

Monitoring of the process and clinical outcomes of implementation

The processes of care (e.g. clinician behaviour, care utilisation patterns, referral and adherence to the guideline) are as important to clinical outcomes as interventions themselves. The monitoring of these, along with their predictive relationships to clinical, social and cost outcomes, may reveal opportunities as well as barriers to be overcome. This monitoring could be done in the context of a well-defined quality assurance system. The construction of regional or national quality databases to monitor the processes of care and their outcomes could be part of such a quality assurance system. This would build upon the local pilots mentioned above, but would be an advance on them, being based on chosen combinations of specific evidence based implementation strategies. These should also be tested for feasibility in local target user groups.

Discussion

From this workshop, there were clear reasons for the need for multidisciplinary parent guidelines (Table 4). Multidisciplinary guidelines were considered not to be more onerous than mono-disciplinary ones, especially when the anticipated reduction in fragmentation and duplication of care is considered. If developed by a multidisciplinary team, a role for their professions is implied, and this should enhance acceptance. However, where there is no teamwork between providers, mono-disciplinary guidelines can be useful and might have networked components within multidisciplinary guidelines. Recommendations to bear in mind when implementing these are presented in Table 5.

Table 4.

Multidisciplinary parent guidelines means

| More credibility |

| Reduced duplication |

| Focus on patient outcomes |

| Focus on interventions and not disciplines |

| More uniform practice and decreased fragmentation |

| Consistent messages to patients across professions |

| Recognition that both end users and other stakeholders (payers, patients and policy-makers) should be involved in development and implementation |

Table 5.

Implementation of mono-disciplinary guidelines requires

| The same language and format as the parent |

| An audience-specific delivery to enhance uptake |

| Recognition of the unique context of the users |

| Endorsement by credible discipline parties (clinical leaders?) to enhance uptake |

Obstacles to guideline implementation in health care suggest the need to research the attitudes and beliefs of the main stakeholders themselves to changing practice [19]. These issues extend well beyond care providers since, even if universally agreed in principle, practical barriers, for example, in the workplace [21], may have to be eliminated before implementation is possible. Efforts will be needed to respond to different stakeholder concerns if the implementation of low back pain guidelines is to work. Practitioners can, for example, become engaged if guideline implementation is a part of a public awareness, educational or research program in which they already have a part (especially, if these are highly interactive).

Conclusions

There was consensus among the participants of this workshop that multidisciplinary guidelines have several advantages compared with mono-disciplinary guidelines regarding content, development and implementation. Research on identification of barriers and strategies to overcome them are direly needed.

References

- 1.Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) Collaborative Group Guideline Development in Europe. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2000;16(4):1039–1049. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300103101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnett AG, Underwood MR, Vickers MR. Effect of UK national guidelines on services to treat patients with acute low back pain: follow-up questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1999;318:919–920. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7188.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird C. Commissioned R & D Programmes: implementation of low back pain guidelines in North Thames. London: NHS Executive; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinical Epidemiology. 1994;review:the. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eccles M, Grimshaw J (1995) Ensuring that guidelines change clinical practice. In: The development and implementation of clinical guidelines. Report of the Clinical Guidelines Working Group. Royal College of General Practitioners, Exeter, pp 12–15

- 6.Emslie CJ, Grimshaw J, Templeton A. Do clinical guidelines improve general practice management and referral of infertile couples?. BMJ. 1993;306:1728–1731. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6894.1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans DW, Foster NE, Vogel S, Breen AC, Pincus T (2003) Implementing evidence-based practice in the UK physical therapy professions: do they want it and do they feel they need it? In: Proceedings of the 5th international forum on low back pain research in primary care. Montreal, Canada

- 8.Grimshaw J, Freemantle N, Wallace S, Russell I, Hurwitz B, Watt I, Long A, Sheldon T. Developing and implementing clinical practice guidelines. Quality Health Care. 1995;4:55–64. doi: 10.1136/qshc.4.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grol R, Dalhuijsen J, Thomas S, in’t Veld C, Rutten G, Mokkink H. Attributes of clinical guidelines that influence use of guidelines in general practice: observational study. BMJ. 1998;317:858–861. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7162.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jamison RN, Gintner L, Rogers JF, Fairchild DG. Disease management for chronic pain: barriers of program implementation with primary care physicians. Pain Med. 2002;3(2):92–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2002.02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Quality Health Care. 1998;7:149–158. doi: 10.1136/qshc.7.3.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langworthy J, Breen A (2003) Auditing the management of acute back pain in primary care: too late to preserve the momentum? In: Proceedings of the 32nd annual scientific meeting of the society for academic primary care, Manchester

- 13.Little P, Smith L, Cantrell T, Chapman J, Langridge J, Pickering R. General practitioners’ management of acute back pain: a survey of reported practice compared with clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1996;312:485–488. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7029.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonald CJ, Hui SL, Smith DM, Tierney WM, Cohen SJ, Weinberger M, McCabe GP. Reminders to physicians from an introspective computer trial. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:130–138. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-1-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McIntosh A, Shaw C. Barriers to patient information provision in primary care: patients’ and general practitioners’ experiences and expectations of information for low back pain. Health Expect. 2003;6:19–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2003.00197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Principles for best practice in clinical audit. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press Ltd; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.NHS Effective Health Care. 1999;2:getting. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes RB. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. CMAJ. 1995;153:1423–1431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pagliari Biomed II Concerted action on changing professional. 2003;practice:a. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Royal College of General Practitioners, Clinical Guidelines Working Group (1995) The development and implementation of clinical guidelines. Royal College of General Practitioners, Exeter

- 21.Scheel IB, Hagen KB, Oxman AD. Active sick leave for patients with back pain: all the players onside but still no action. Spine. 2002;27(6):654–659. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200203150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schers H, Braspenning J, Drijver R. Low back pain in general practice: reported management and reasons for not adhering to the guidelines in the Netherlands. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:640–644. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sweeney G, Stead J, Sweeney K, Greco M. Exploring the implementation and development of clinical governance in primary care within the South West Region: views from PCG Clinical Governance Leads. Exeter: NHS Executive South West Region-Research & Development Support Unit; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorsen Changing professional. 1999;practice:theory. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tulder MW, Croft PR, Splunteren P, Miedema HS, Underwood MR, Hendricks HJM, Wyatt ME, Borkan JM. Disseminating and implementing the results of back pain research. Spine. 2002;27(5):E121–E127. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200203010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watkins C, Harvey I, Langley C, Gray S, Faulkner A. General practitioners’ use of guidelines in the consultation and their attitudes to them. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49:11–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]