Abstract

Very few studies have investigated the effects or costs of rehabilitation regimens following lumbar spinal fusion. The effectiveness of in-hospital rehabilitation regimens has substantial impact on patients’ demands in the primary health care sector. The aim of this study was to investigate patient-articulated demands to the primary health care sector following lumbar spinal fusion and three different in-hospital rehabilitation regimens in a prospective, randomized study with a 2-year follow-up. Ninety patients were randomized 3 months post lumbar spinal fusion to either a ‘video’ group (one-time oral instruction by a physiotherapist and patients were then issued a video for home exercise), or a ‘café’ group (video regimen with the addition of three café meetings with other fusion-operated patients) or a ‘training’ group (exercise therapy; physiotherapist-guided; two times a week for 8 weeks). Register data of service utilization in the primary health care sector were collected from the time of randomization through 24 months postsurgery. Costs of in-hospital protocols were estimated and the service utilization in the primary health care sector and its cost were analyzed. A significant difference (P=0.023) in number of contacts was found among groups at 2-year follow-up. Within the periods of 3–6 months and 7–12 months postoperatively, the experimental groups required less than half the amount of care within the primary health care sector as compared to the video group (P=0.001 and P=0.008). The incremental costs of the café regimen respectively, the training regimen were compensated by cost savings in the primary health care sector, at ratios of 4.70 (95% CI 4.64; 4.77) and 1.70 (95% CI 1.68; 1.72). This study concludes that a low-cost biopsychosocial rehabilitation regimen significantly reduces service utilization in the primary health care sector as compared to the usual regimen and a training exercise regimen. The results stress the importance of a cognitive element of coping in a rehabilitation program.

Keywords: Lumbar spinal fusion, Rehabilitation, Primary care, Costs and cost analysis

Introduction

Very few studies have investigated the effects or costs of rehabilitation regimens following lumbar spinal fusion. This is despite the fact that evidence of different surgical interventions continues to grow [1–5, 14, 15]. Focusing on lumbar disc surgery, a recent review by Ostelo et al. [17] concludes that there is convincing evidence for implementing exercise programs 4–6 weeks postoperatively but that the exact content of a rehabilitation program is unclear and needs investigation. In a recent study, we found a significantly improved outcome in patients randomized to a low-cost rehabilitation protocol which incorporates a behavioral element of coping strategies in comparison to patients randomized to the video instruction or repetitive exercise therapy after lumbar spinal fusion [3]. A crucial issue is whether this outcome demonstrated by the low-cost regimen is at the expense of an increased incidence of contacts in the primary health care sector.

The aim of the present study is to investigate patients’ demands to the primary health care sector via the evaluation of three in-hospital rehabilitation programs. We hypothesize that a comprehensive in-hospital rehabilitation regimen provides cost savings within the primary health care sector, which exceed the incremental cost of providing such a regimen.

Materials and methods

Subjects and design

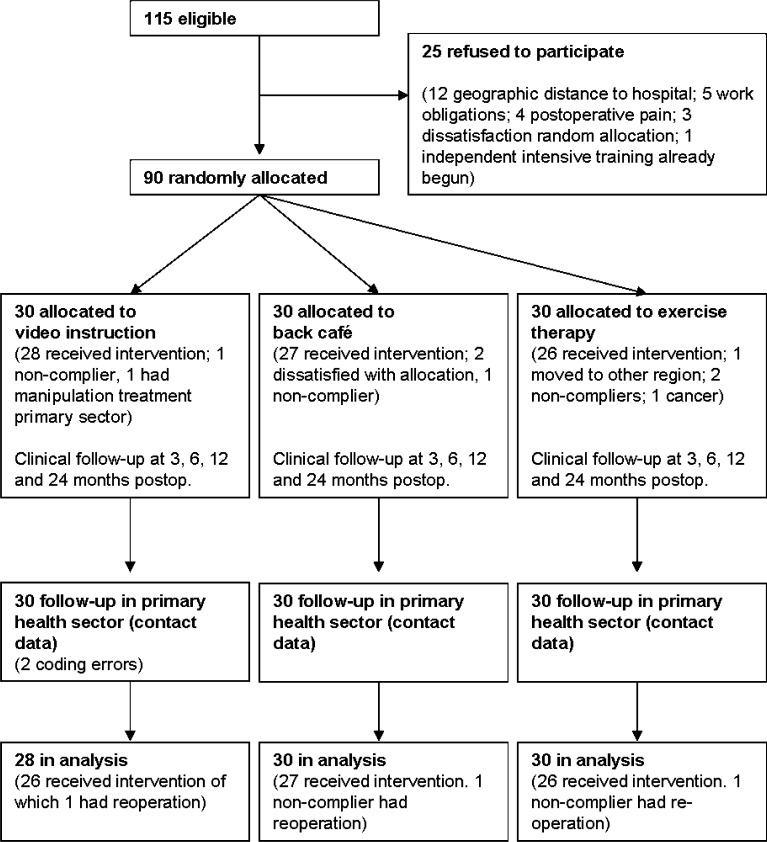

One hundred and fifteen patients who had undergone lumbar spinal fusion were invited to participate in the study. Figure 1 illustrates the flow of participants. Upon informed consent, 90 patients were included for randomization to the three rehabilitation therapy protocols via sealed envelopes. Eligibility criteria comprised preoperative, severe and chronic (persistent through 2 years) low back pain (LBP) due to localized lumbar or lumbosacral segmental instability, treated surgically by circumferential (33 patients) or posterolateral (57 patients) spinal fusion. Exclusion criteria were age outside the range of 20–65 years, one or more co-morbidities such as metabolic bone disease (including osteoporosis), clinical signs of nerve root compression postoperatively (at the time of randomization), psychosocial instability or residence outside the county. Indication for fusion was determined on the basis of symptomatic history, multiple clinical and neurologic examinations, psychosocial status (assessed qualitatively by the surgeon), plain radiography, and supplementary CT/myelography and/or MRI. Diagnoses were isthmic spondylolisthesis (32 patients), primary degeneration (31 patients) and degeneration secondary to prior fusion or accelerating degeneration after decompressive surgery (27 patients). Surgeries were performed from August 1996 to May 1999 with clinical follow-up of 3, 6, 12 and 24 months post surgery. Baseline data were collected in the course of the 3-month postoperative clinical follow-up at the outpatient clinics. Subjects were randomized from two blocks based on surgical technique (circumferential or posterolateral fusion) 1 week after the 3-month clinical follow-up. Investigation was blinded to practitioners within the primary health care sector.

Fig. 1.

Patient flow in a RCT of three rehabilitation regimens investigating service utilization in the primary health sector. Aarhus, 1996–2002

Protocol 1: video group

In a group session at the hospital, the video group participants watched an instructional video tape of exercises intended for the patients’ individual home training. As a means of support, a rehabilitation physiotherapist (RPT) orally instructed the patients in the exercises presented on the video. At the close of this introductory meeting of approximately 1.5 h, patients were issued a copy of the video tape for subsequent review at home and consequently, patients were expected to carry out the training independently at home. This regimen represents the hospital’s usual rehabilitation approach for lumbar spinal fusion patients.

Protocol 2: café group

A café group was provided the same introduction and video tape hand-out as group 1 and additionally, the patients were encouraged to participate in three meetings of approximately 1.5 h each with other fusion-operated patients during an 8-week period. The meetings were set up informally as a back-café with the participation of ten patients and a RPT per meeting to provide an opportunity for exchanging experiences of pain, functional ability, etc.

Protocol 3: training group

A training group was provided individual training therapy in the physiotherapy department of the hospital twice weekly for 8 weeks. Training was based upon individual training programs and was monitored by a RPT to augment the patients’ motivation and to gradually increase training intensity via increased repetitions and number of series in each training session. Each training session lasted approximately 1 h and included condition training, dynamic muscular endurance training and stretching exercises. Dynamic muscular endurance training was focused on the back, abdominal and leg groups and was conducted at a rhythmic tempo of seven to ten repetitions followed by short pauses. The training group was encouraged to continue their normal daily activities. They were not specifically encouraged to conduct additional training to the exercise therapy program at the hospital.

Register data

The Danish Health Insurance agency, which registers all contacts within the primary health care sector, collected the register data. The overall observation period was established as November 1996 through August 2002. Primary health care sector is defined as all authorized practitioners not employed by hospitals, in this context, primarily general practitioners (GPs), physiotherapists (PTs), psychiatrists, psychologists, chiropractors, rheumatologists and neurologists.

Outcome

Outcome was measured by the cost of in-hospital rehabilitation regimen minus the cost of contacts in the primary health care sector. The observation period was established from the time of randomization to 24 months postoperatively.

Cost analysis

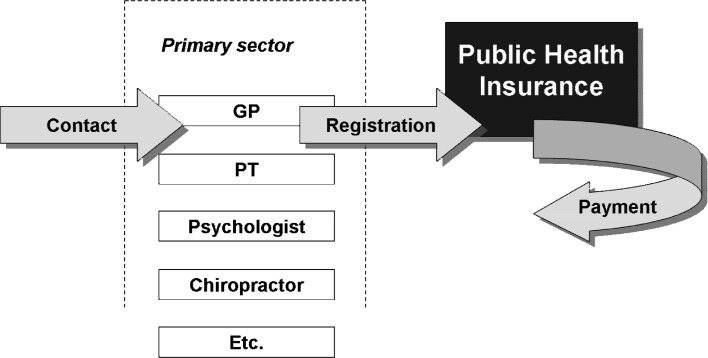

The health care sector’s viewpoint was adapted. In-hospital therapy protocols and logs provided measurement of rehabilitation regimen and monetary value was calculated bottom-up. Each contact to the primary health care sector is uniquely and prospectively registered by the Danish Health Insurance with a code indicating practitioner, type of treatment, date, cost and social security number. This process is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Prospective registration of contacts in the Danish primary health care sector. The universal health insurance requires full registration prior to payment. Price index is negotiated every second year by practitioner’s societies

A prefixed, contractual price index is adapted from the Danish Health Insurance and practitioners’ national societies. Cost variations in the course of time are implemented from index regulations every second year. For example, the marginal cost (year 2000) of a consultation at a GP was EUR 12.03 1. All costs are converted from Danish Crowns (DKK) into Euro (EUR) using the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) provided by the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) [16, 19].

Clinical study

Clinical outcome was assessed in terms of functional outcome, pain and satisfaction and has been previously reported by Christensen et al. [3]. Subsets from these data have been merged with register data to form background data. Background data comprises social security number, random code, age, gender, diagnosis, back pain, leg pain, occupational status and patient-perceived life quality.

Dropouts

Flow of participants and patient-reported reasons for drop out is illustrated in Fig. 1. In the course of collecting register data, two subjects had to be excluded as their social security numbers appeared invalid, possibly due to coding error while requesting extracts from the register database. Intention-to-treat analysis was performed (n=88). Further, the impact on conclusions of analysis per protocol (n=79) were investigated by parallel analysis of patient’s demands to the primary health care sector.

Calculation and statistical evaluation

Register data were restructured, controlled for logic errors and, by means of the statistical software SPSS, validated statistically into an observation set of date, practitioner/field, type of contact/treatment code, marginal cost and social security number. Observations irrelevant to the investigation at hand (e.g., dental services) were excluded on the basis of a programmed SPSS syntax identifying type of contact derived from practitioner-coding and treatment-coding. Three observation intervals (3–6 months, 7–12 months and 13–24 months) reflecting the regimens of clinical follow-up were introduced. Finally, an observation set was aggregated from contact level (n=4,935) to patient level (n=88) and merged with clinical data keyed by social security number.

Nonparametric statistics of Kruskal Wallis and Mann–Whitney U tests (Wilcoxon) were applied in order to analyze for differences among groups by means of the statistical software SPSS. The 5% two-tailed limit of statistical significance was used for all tests.

The Ethical Committee of Aarhus approved this study on 28 February 1996. Permission for the collection and analysis of register data was granted by the Danish Data Protection Agency on 16 February 2000.

Results

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the randomization groups. To our surprise, the random variation produced a relatively skewed distribution of females among groups (video 82%, café 50% and training 67%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 88 lumbar spinal fusion patients by the time of randomization for different rehabilitation regimens. Aarhus, 1996–2000. Values are number of patients unless otherwise stated

| Video group (n=28) | Café group (n=30) | Training group (n=30) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Median years | 45 | 47 | 48 |

| Gender | Females | 23 | 15 | 20 |

| Diagnosis | Isthmic spondylolisthesis | 9 | 14 | 9 |

| Primary degeneration | 9 | 8 | 12 | |

| Secondary degenerationa | 10 | 8 | 9 | |

| Back pain [0; 10] | Median within last 14 days (range) | 4.0 (0–8) | 4.0 (0–7) | 2.0 (0–8) |

| Leg pain [0; 10] | Median within last 14 days (range) | 1.0 (0–10) | 2.0 (0–8) | 1.0 (0–7) |

| Occupational status | Related to labour market | 8 | 15 | 10 |

| Life quality [0; 5] | Median (range) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) | 1 (1–5) |

aSecondary to previous surgery

Incremental costs of providing rehabilitation regimens to 30 patients were calculated; video amounted to EUR 1,585 2 (baseline), café amounted to EUR 2,749 3 and training amounted to EUR 7,355 4.

Table 2 illustrates patients’ service utilization in the primary health care sector. A total of 4,932 contacts to the primary health care sector were registered during the follow-up period: 52.6% within the video group, 22.6% within the café group and 24.8% within the training group. A significant difference was evident when comparing the three randomization groups (P=0.023). At intervals of 3–6 months and 7–12 months post surgery, the difference among the groups was highly significant (P=0.001 and P=0.008) whereas the interval of 13–24 months post surgery did not exhibit significant differences among the groups, although the café group demonstrated a tendency to demand less service when compared to both the video and training groups.

Table 2.

Lumbar spinal fusion patients’ contacts in the primary health care sector following three in-hospital rehabilitation regimens (intention-to-treat, n=88). Aarhus, 1996–2000

| 3–6 | 7–12 | 13–24 | Cumulative period | Contact count | Percent | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | SEmean (mean) | Median | SEmean (mean) | Median | SEmean (mean) | Median | SEmean (mean) | |||

| Video | 8.0 | 5.0 (19) | 15.0 | 7.4 (30) | 19.5 | 12.0 (44) | 50.5 | 22.7 (93) | 2593 | 52.6 |

| Café | 3.0 | 1.0 (4) | 7.0 | 3.2 (12) | 16.0 | 4.0 (21) | 30.0 | 6.6 (37) | 1114 | 22.6 |

| Training | 1.5 | 1.1 (4) | 5.5 | 4.9 (14) | 16.0 | 4.1 (23) | 24.0 | 8.6 (41) | 1225 | 24.8 |

| Total | 3.0 | 1.8 (9) | 8.0 | 3.2 (18) | 17.5 | 4.4 (29) | 31.5 | 8.4 (56) | 4932 | 100.0 |

| P valuea | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.278 | 0.023 | ||||||

Contacts are distributed in intervals of follow-up (months post surgery)

aKruskal Wallis test

Table 3 illustrates the effect of dropouts in relation to the analyzed demand presented in Table 2. The nine subjects (10.2%), who did not comply with protocols accounted for 1,228 contacts (24.8%) to the primary health care sector, which suggests that dropouts are characterized by a heavy demand for therapy and treatment. However, the findings presented in Table 2 persist when conducting per protocol analysis: significantly different patient-demands among groups in the first two intervals of follow-up (P=0.005 and P=0.029) and further, of cumulative follow-up period (P=0.06).

Table 3.

Per protocol analysis (n=79) of patient’ contacts in the primary health sector following three in-hospital rehabilitation regimens. Aarhus, 1996–2000.

| 3–6 | 7–12 | 13–24 | Cumulative period | Contact count | Percent | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | SEmean (mean) | Median | SEmean (mean) | Median | SEmean (mean) | Median | SEmean (mean) | |||

| Video | 8.0 | 4.0 (15) | 13.5 | 5.9 (23) | 17.5 | 5.6 (29) | 38.5 | 13.5 (66) | 1723 | 45.3 |

| Café | 3.0 | 1.1 (5) | 7.0 | 3.5 (12) | 15.0 | 4.4 (21) | 29.0 | 7.2 (38) | 1028 | 27.0 |

| Training | 1.5 | 1.2 (4) | 5.0 | 5.7 (15) | 12.0 | 4.5 (22) | 20.5 | 9.7 (41) | 1053 | 27.7 |

| Total | 3.0 | 1.8 (9) | 8.0 | 3.2 (18) | 17.5 | 4.4 (29) | 31.5 | 8.4 (56) | 3804 | 100.0 |

| P valuea | 0.005 | 0.029 | 0.477 | 0.060 | ||||||

Contacts are distributed in intervals of follow-up (months post surgery)

aKruskal Wallis test

Table 4 presents the distribution of the demand within primary health care sector. Comparison of randomization groups did not suggest significant difference (P>0.128) in relation to neither ratio of contact toward fields of specialization within primary health care sector nor with regard to distribution relative to cumulative demand within each interval. Thus, randomization groups presented are aggregated. Patient’s demands to GPs accounted for approximately half of all contacts throughout the cumulative period: from 52% of all contacts in the first interval, 47% in the second to 53% in the third. Additionally, demands toward PTs accounted for 44% of contacts in the first interval, 50% in the second and 42% within the third interval of follow-up. Other contacts, for example, to psychologists, rheumatologists and physiologists, accounted for less than 5% in the cumulative follow-up period. Dropouts were characterized by relatively heavier demand for physiotherapy in all intervals of follow-up. Thus, excluding dropouts influenced distribution among fields of specialization by increasing the proportion of contacts to GPs while decreasing demands to physiotherapy.

Table 4.

Lumbar spinal fusion patients’ contacts in the primary health sector (n=88) following in-hospital rehabilitation. Aarhus, 1996–2000

| 3–6 | 7–12 | 13–24 | Cumulative period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| General practitioners | 412 (377) | 52.0 (61.6) | 753 (671) | 46.9 (51.7) | 1349 (1139) | 53.2 (60.1) | 2514 (2187) | 51.0 (57.7) |

| Physiotherapists | 348 (210) | 43.9 (34.3) | 796 (571) | 49.6 (44.0) | 1069 (667) | 42.2 (35.2) | 2213 (1448) | 44.9 (38.1) |

| Psychiatrics or psychologists | 7 (7) | 0.9 (1.1) | 14 (14) | 0.9 (1.1) | 26 (2) | 1.0 (0.1) | 47 (23) | 1.0 (0.6) |

| Rheumatologists or physiologists | 7 (-) | 0.9 (-) | 18 (18) | 1.1 (1.4) | 16 (13) | 0.6 (0.7) | 41 (31) | 0.8 (0.8) |

| Chiropractors | 1 (1) | 0.1 (0.2) | 13 (11) | 0.8 (0.8) | 16 (16) | 0.6 (0.8) | 30 (28) | 0.6 (0.7) |

| Others | 17 (17) | 2.1 (2.8) | 12 (12) | 0.7 (0.9) | 58 (58) | 2.3 (3.1) | 87 (87) | 1.8 (2.3) |

| Total | 792 (612) | 100.0 (100.0) | 1,606 (1,297) | 100.0 (100.0) | 2,534 (1,895) | 100.0 (100.0) | 4,932 (3,804) | 100.0 (100.0) |

Contacts are distributed in intervals of follow-up (months post surgery). In bracket, per protocol analysis (n=79)

Table 5 illustrates the total costs of investigated demands to the primary health care sector. The grand total costs are EUR 24,029 for the video group, EUR 11,101 for the café group and EUR 11,537 for the training group. Thus, the attachment of monetary values to number of contacts (Table 1) does not significantly alter the findings and tendencies previously concluded; greater demands are found within the video group both cumulatively (P=0.045) and within the first two intervals of 3–6 months and 7–12 months post surgery (P=0.006 and P=0.018).

Table 5.

Costs of lumbar spinal fusion patients’ contacts in the primary health sector following three in-hospital rehabilitation regimens (EUR). Aarhus, 1996–2000

| 3–6 | 7–12 | 13–24 | Cumulative 3–24 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum | Median | SEmean (mean) | Sum | Median | SEmean (mean) | Sum | Median | SEmean (mean) | Sum | Median | SE mean (mean) | |

| Video (n=28) | 4,560 | 53 | 52 (163) | 7,933 | 98 | 79 (283) | 11,536 | 149 | 136 (412) | 24,029 | 400 | 243 (858) |

| Café (n=30) | 1,338 | 16 | 16 (45) | 3,192 | 39 | 31 (106) | 6,572 | 98 | 77 (219) | 11,101 | 213 | 104 (370) |

| Training (n=30) | 1,365 | 12 | 19 (46) | 3,416 | 37 | 38 (114) | 6,756 | 111 | 50 (225) | 11,537 | 203 | 80 (385) |

| Total | 7,263 | 18 | 19 (83) | 14,541 | 50 | 31 (165) | 24,864 | 127 | 54 (283) | 46,667 | 239 | 92 (530) |

| P valuea | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.306 | 0.045 | ||||||||

Costs are distributed in intervals of follow-up (months post surgery)

aKruskal Wallis test

The influence of dropouts was analyzed in relation to the grand total of costs. In the video group, significantly different cost profiles were detected when dropouts were compared to compliers. The two patients who were dropouts in the video group (7% of 28 subjects) accounted for a total cost of EUR 9,696 (40% of total video group cost). In the other two groups, the dropouts’ cost profile did not differ significantly from the compliers’ cost profile. Hence, excluding dropouts affected the overall difference between randomization groups within all intervals of follow-up: the 3–6 months interval was still significant (P=0.026), the interval of 7–12 exhibited a clear tendency (P=0.068), whereas the overall period of follow-up proved not to be significantly different among the groups (P=0.131).

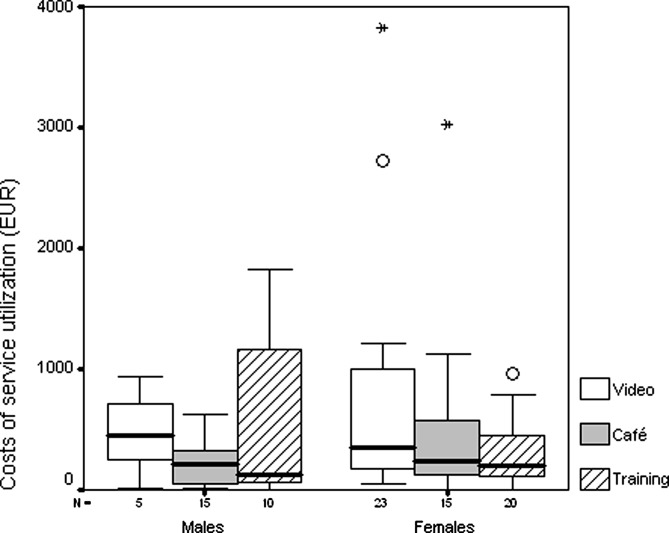

Table 6 shows a secondary analysis of cumulative costs per gender, diagnosis and reoperation versus no reoperation. The distribution of total costs per gender demonstrates a possible difference between males and females (P=0.113). Figure 3 shows the distribution of costs per gender within the three groups. It is evident that outliers and extremes are females and that service utilization is indeed characterized by great variation.

Table 6.

Costs of patient’s demands to primary health sector (following lumbar spinal fusion) stratified in gender, diagnosis and reoperation. Aarhus, 1996–2000

| Median cost per patientc EUR (mean/SEmean) [range] | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female (n=58) | 247 (622/132) | 0.113d |

| Male (n=30) | 213 (353/80) | ||

| Diagnosis | Isthmic spondylolisthesis (n=32) | 274 (469/96) | 0.647e |

| Primary degeneration (n=29) | 206 (324/59) | ||

| Secondary degenerationa (n=27) | 204 (824/263) | ||

| Reoperationb | Yes (n=3) | 334 [203;403] | Not relevant |

| No (n=85) | 245 [0;5,875] |

aSecondary to previous surgery

bWithin period of time from spinal fusion through 24 months follow-up

cCumulative costs at 24 months postoperative

d Mann-Whitney U test

eKruskal-Wallis test

Fig. 3.

Costs (EUR) of patient’s demands to the primary health sector after lumbar spinal fusion (horisontal line is median, boxes are 25- and 75-percentiles and whiskers are interquartiles). Aarhus, 1996–2002

Our population suffered three reoperations distributed with one in each intervention group. In the café group one patient had the posterior instrumentation removed and was re-fused by a circumferential approach 420 days after index surgery. In each of the the video and the training groups, one patient had the instrumentation removed and was re-fused by an uninstrumented approach (in the video group 234 days after index surgery and in the training group 608 days after index surgery). From Table 6, no evident difference in these three patients’ service utilization compared to those not suffering reoperation in the follow-up period is seen. According to the present case-mix system implemented in the blinded hospital sector, the 2004 costs of such reoperations would amount to EUR 11,248 (instrumented fusion) and EUR 7,538 (uninstrumented fusion) for the hospital admission and operation alone [21]. An admission for an uninstrumented spinal fusion equals approximately 500 visits to a general practitioner or 350 standard treatments at a physiotherapist [22].

Conclusively, the findings confirm the introduced hypothesis that both the café and training approaches generate cost savings in the primary health care sector to a level which exceeds the incremental cost of providing these regimens (compared to video). The café approach provided a cost ratio of 4.70 (95% CI 4.64; 4.77) and the training approach provided a cost ratio of 1.70 (95% CI 1.68; 1.72).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge our previously reported study is the first RCT investigating the effect of different rehabilitation regimens following lumbar spinal fusion [3]. We found that the café approach significantly improves outcome in comparison to training exercise. These findings stand in the light of a relatively simple concept consisting of initial instruction and three meetings with other patients, which raised the question as to whether the more impressive performance is at the expense of increased service utilization in the primary health care sector. In the present study, we found that this superior performance of the café group in no way imposes heavier demands on the primary health care sector. Hence, our findings suggest a significant effect from the incorporation of even a limited behavioral element. This comply with findings in chronic LBP patients treated conservatively [6, 10, 23, 24]. On the other hand, a recent review of 12 RCTs by Guzman et al. [8] concluded the existence of evidence for an intensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation but did not find evidence for a light multidisciplinary approach.

This study was conducted as a cost analysis from a health care sector’s viewpoint. The point of reference was a dominant intervention from a hospital’s perspective as the café approach demonstrated superior performance at less expense compared to training. Thus, a cost analysis covering the primary sector seemed a relevant method to investigate patient’s extra-hospital service utilization [7, 9]. It should be mentioned that, from a socioeconomic point of view, the far greatest impact is caused by loss of health-related life quality and the ability to contribute to production. These cost categories exceed health care costs multiple times [12, 13].

The cost of reoperations and rehospitalizations were not included. This activity, if occurring, does of course represent significant costs to the hospital sector and thus, the true costs of the postoperative regimen might be underestimated. In this particular sample of patients, inclusion of the costs of reoperations would not affect conclusions as the three reoperations occurring were distributed by one in each intervention group.

Randomization and inclusion in this study were blinded to practitioners in the primary health care sector and selection of patients was conducted by a surgeon in agreement with eligibility criteria identical to those implemented in every-day practice. Still, of course neither the physiotherapist performing the therapy or being present at the café meetings nor the patients were blinded. We do however believe this has not biased the findings significantly as neither the physiotherapist nor the patients knew about the cost analysis or the collection of data from the primary health care sector.

Twenty-five patients refused to participate due to known reasons. Of these, four (3.5%) reported postoperative pain as the reason and three (2.6%) objected to the principles of random allocation. The rest (15.7%) reported various reasons regarded as irrelevant to outcome evaluation. It would indeed be of particular interest in a future study to investigate the service utilization of patients who refuse to participate.

A crucial point of the study was the statistically skewed distribution of females among groups although randomly allocated (video 82%, café 50% and training 67%). Other studies have found females and males to respond differently to light and intensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation [20] and to rehabilitation in general [18]. In the present study, there was a nonsignificant tendency for the postoperative primary care costs to be lower for men. Further, females are known to visit their GPs more often than males regardless of back disease [11]. The skewed distribution of males and females in each group after randomization (predominance of men in café group) might have contributed to a slight overestimation of the effect of the back café approach; this issue may require further investigation.

Nine patients did not comply with protocols due to known reasons. The dropouts’ total demands were within the range of the demand shown by those patients who complied with the protocols of the café and training groups. Interestingly, the dropouts in the video group expressed a significantly greater demand than those complying with the protocol. These subjects represented 10.2% of the randomization group, whereas they accounted for 24.8% of the total demand. However, the conclusion in favor of the café group remained significant despite exclusion of dropouts from our analysis.

Analysis of sensitivity was conducted in order to visualize validity of findings: a 25% under-reporting of the demand to the primary health care sector would, if undifferentiated among the three groups, support these findings. A differentiated under-reporting of 25% in favor of the video approach would return alternative cost ratios of 3.69 (café group) and 1.31 (training group). Questioning the cost estimates of therapy protocols would also have limited effect; a differentiated increase of 25% in favor of the video approach would return cost ratios of 3.37 (café group) and 1.30 (training group). Combining the above worst-case scenarios would return cost ratios of 2.65 (café group) and 1.00 (training group) which obviously still emphasize a highly significant conclusion.

Another evident issue for discussion is the length of follow-up. We have chosen a period reflecting our regimen of clinical follow-up, which is 2 years postsurgery. In accordance with this prerequisite, the differences among the groups seem to decline in the course of a 13–24 months post surgery interval why the period of follow-up seems sufficient.

In our previous study we found the video group to perform worse than the other two groups in relation to function ability [3]. In the present study, we found the video group to hold the greatest service utilization in the primary health sector at the same time. Despite the greatest service utilization, the video group performs worse. Did the video group seek this extra service because they were symtomatically worse off or did any treatment offered not alleviate their symtoms? Should the video group not have received this extra service compared to the other groups, the group might have been even worse off and hence, we might have underestimated the effect of the other regimens.

This study has shown that a low-cost biopsychosocial rehabilitation regimen reduces service utilization in the primary health care sector compared to a training regimen. To our knowledge, this is the first rehabilitation study in LBP, approached surgically, that investigates extra-hospital service utilization in a relevant scientific setting. It would indeed be interesting for future studies to supplement outcome evaluation by such an approach, if not a full-scale cost-effectiveness analysis.

Footnotes

Approximately two thirds of the GP’s invoicing basis is activity-based; one third is fixed

Video tape EUR 185, personnel EUR 773, overhead costs EUR 627=EUR 1,585

Personnel and variable costs EUR 348, overhead costs EUR 2,401=EUR 2,749.

Personnel and variable costs EUR 3,441, overhead costs EUR 5,499—cost of video regimen EUR 1,585=EUR 7,355.

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00586-006-1079-7

References

- 1.Christensen FB, Hansen ES, Eiskjaer SP, Hoy K, Helmig P, Neumann P, et al. Circumferential lumbar spinal fusion with Brantigan cage versus posterolateral fusion with titanium Cotrel–Dubousset instrumentation: a prospective, randomized clinical study of 146 patients. Spine. 2002;23:2674–2683. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen FB, Hansen ES, Laursen M, Thomsen K, Bunger CE. Long-term functional outcome of pedicle screw instrumentation as a support for posterolateral spinal fusion: randomized clinical study with a 5-year follow-up. Spine. 2002;12:1269–1277. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen FB, Laurberg I, Bünger CE. Importance of the back-cafe concept to rehabilitation after lumbar spinal fusion: a randomized clinical study with a 2-year follow-up. Spine. 2003;28:2561–2569. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000097890.96524.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fritzell P, Hagg O, Wessberg P, Nordwall A. 2001 Volvo Award Winner in clinical studies: Lumbar fusion versus nonsurgical treatment for chronic low back pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Spine. 2001;23:2521–2532. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200112010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fritzell P, Hagg O, Wessberg P, Nordwall A. Chronic low back pain and fusion: a comparison of three surgical techniques: a prospective multicenter randomized study from the Swedish lumbar spine study group. Spine. 2002;11:1131–1141. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goossens ME, Rutten-Van Molken MP, Kole-Snijders AM, Vlaeyen JW, Van Breukelen G, Leidl R. Health economic assessment of behavioural rehabilitation in chronic low back pain: a randomised clinical trial. Health Econ. 1998;1:39–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(199802)7:1<39::AID-HEC323>3.3.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graves N, Walker D, Raine R, Hutchings A, Roberts JA. Cost data for individual patients included in clinical studies: no amount of statistical analysis can compensate for inadequate costing methods. Health Econ. 2002;8:735–739. doi: 10.1002/hec.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guzman J, Esmail R, Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Irvin E, Bombardier C. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2001;7301:1511–1516. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7301.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jefferson T, Smith R, Yee Y, Drummond M, Pratt M, Gale R. Evaluating the BMJ guidelines for economic submissions: prospective audit of economic submissions to BMJ and the Lancet. JAMA. 1998;3:275–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kole-Snijders AM, Vlaeyen JW, Goossens ME, Rutten-Van Molken MP, Heuts PH, Van Breukelen G, et al. Chronic low-back pain: what does cognitive coping skills training add to operant behavioral treatment? Results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;6:931–944. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krasnik A, Hansen E, Keiding N, Sawitz A. Determinants of general practice utilization in Denmark. Dan Med Bull. 1997;5:542–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maetzel A, Li L. The economic burden of low back pain: a review of studies published between 1996 and 2001. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2002;1:23–30. doi: 10.1053/berh.2001.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maniadakis N, Gray A. The economic burden of back pain in the UK. Pain. 2000;1:95–103. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moller H, Hedlund R. Surgery versus conservative management in adult isthmic spondylolisthesis—a prospective randomized study: part 1. Spine. 2000;13:1711–1715. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200007010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moller H, Hedlund R. Instrumented and noninstrumented posterolateral fusion in adult spondylolisthesis—a prospective randomized study: part 2. Spine. 2000;13:1716–1721. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200007010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2002) Purchasing power parities and real expenditures—1999 Benchmark Year. OECD Report no. 7

- 17.Ostelo RW, Vet HC, Waddell G, Kerckhoffs MR, Leffers P, Tulder M. Rehabilitation following first-time lumbar disc surgery: a systematic review within the framework of the cochrane collaboration. Spine. 2003;3:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200302010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt B, Kolip P, Greitemann B. Gender-specific aspects in chronic low back pain rehabilitation. Rehabilitation (Stuttg) 2001;5:261–266. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schreyer P, Koechlin F (2002) Purchasing power parities—measurement and uses. OECD Report no. 3

- 20.Skouen JS, Grasdal AL, Haldorsen EM, Ursin H. Relative cost-effectiveness of extensive and light multidisciplinary treatment programs versus treatment as usual for patients with chronic low back pain on long-term sick leave: randomized controlled study. Spine. 2002;9:901–909. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200205010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The The Danish National Board of. 2004;Health:Casemix. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The National Health Insurance Board [Takstkortoversigt] (1-10-2002) The Danish National Health Insurance Board. The Danish National Board of Health

- 23.Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ, Morley SJ, Assendelft WJ. Behavioral treatment for chronic low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine. 2000;20:2688–2699. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200010150-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vlaeyen JW, Haazen IW, Schuerman JA, Kole-Snijders AM, Eek H. Behavioural rehabilitation of chronic low back pain: comparison of an operant treatment, an operant-cognitive treatment and an operant-respondent treatment. Br J Clin Psychol. 1995;34:95–118. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1995.tb01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]