Abstract

Objectives. We measured the burden of hypothermia- and hyperthermia-related health care visits, identified risk factors, and determined the health care costs associated with environmental heat or cold exposure among Medicare beneficiaries.

Methods. We obtained Medicare fee-for-service claims data of inpatient and outpatient health care visits for hypothermia and hyperthermia from 2004 to 2005. We examined the distribution and differences of visits by age, sex, race, geographic regions, and direct costs. We estimated rate ratios to determine risk factors.

Results. Hyperthermia-related visits (n = 10 007) were more frequent than hypothermia-related visits (n = 8761) for both years. However, hypothermia-related visits resulted in more deaths (359 vs 42), higher mortality rates (0.50 per 100 000 vs 0.06 per 100 000), higher inpatient rates (5.29 per 100 000 vs 1.76 per 100 000), longer hospital stays (median days = 4 vs 2), and higher total health care costs ($98 million vs $36 million).

Conclusions. This study highlighted the magnitude of these preventable conditions among older adults and disabled persons and the burden on the Medicare system. These results can help target public education and preparedness activities for extreme weather events.

Older adults (≥ 65 years) and persons with chronic diseases are at risk for heat- and cold-related mortality and morbidity during extreme ambient temperatures.1–3 Even slight changes in temperature can adversely affect these populations because of their weakened physiological adaptability and socioeconomic factors.1,4 As the growing evidence of global climate change supports anticipated increases in the intensity and frequency of heat waves and extreme cold events, older adults and those with chronic diseases will be at an increased risk for hyperthermia and hypothermia.1,5

The US Census Bureau projects that the number of older adults will rapidly increase during the 2010 to 2030 period. Accordingly, it is projected that by 2030, the older population will be 2 times greater than in 2000, growing from 35 million to 72 million, or nearly 20% of the total US population.6

Little has been published on national incidence rates, risk factors, and associated health care costs of heat- and cold-related mortality and morbidity among older adults. The purpose of this study was therefore to measure the burden of hypothermia- and hyperthermia-related health care visits, identify risk factors, and estimate the direct health care costs associated with environmental exposure to heat or cold among Medicare beneficiaries. Medicare is the nation’s largest health insurance program and covers nearly 40 million Americans aged 65 years and older and persons with eligible disabilities (e.g., persons with a debilitating physical or mental disease or end-stage renal disease).7

Findings from this study can guide preparedness planning to better target public health messaging to older Americans, disabled persons, their caregivers, and health care professionals to reduce the health effects of hot and cold weather events. In addition, we anticipate that organizations such as the Healthy Aging Research Network and the Healthy Aging Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) can use these findings to support their efforts to promote and protect the health of older adults during extreme weather events.

METHODS

Our population consisted of Medicare beneficiaries with fee-for-service claims for inpatient or outpatient medical visits for hypothermia or hyperthermia during 2004 to 2005. We obtained 2 Medicare data files from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS): the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) file for inpatient visits and the Outpatient Claims file for outpatient visits.

The MEDPAR file contained claims for all admissions to Medicare-certified inpatient hospitals and skilled nursing facilities. These inpatient visits were summarized in the MEDPAR file as a single hospital stay record.

The Outpatient Claims file captured all outpatient visits, including visits to hospital outpatient clinics, rural clinics, and emergency departments (EDs) not resulting in hospital admission. Each record represents a single claim. If an outpatient visit required hospitalization, then the outpatient visit and subsequent hospital admission were combined as 1 record and reported in the MEDPAR file.

All visits with a diagnosis under the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)8 diagnosis code 991 (effects of reduced temperature) were defined as hypothermia visits, and files with a diagnosis under the ICD-9-CM diagnosis code 992 (effects of heat and light) were defined as hyperthermia visits. We limited our inclusion criteria to the first listed primary ICD-9-CM diagnosis only because of the general incompleteness of reporting of secondary diagnoses and E-codes of submitted claims. For denominator data, we used the total number of Medicare fee-for-service enrollees as of July 1, 2006, available online from CMS.9

Demographic and service use data (i.e., ED visits, intensive care unit [ICU] stays, and health care costs) were available for each record. Covariates of interest were level and length of care, age, sex, race/ethnicity, state of residence, discharge status, and direct health care cost data.

Three data sets were created for analysis. The first data set contained all extracted hypothermia and hyperthermia inpatient and skilled nursing facility visits from the MEDPAR database. The second data set contained all outpatient hypothermia- and hyperthermia-related visits recorded in the outpatient database. We used these 2 data sets to measure the burden of hypothermia and hyperthermia, to identify risk factors, and to calculate associated health care cost. Our final data set included hypothermia and hyperthermia claims from the MEDPAR and outpatient databases that accessed ED services. To identify ED services in the outpatient database, we used revenue center code values 0450 to 0459 and 0981 and extracted those visits.10 In the MEDPAR database, if the ED cost variable was 0, we assumed that the hospital admission was a direct admit (admission was not preceded by an ED visit); therefore, those were excluded from the ED database. We used this ED data set to calculate annual ED incidence rates and to measure illness severity by using outcome (i.e., died, admitted, or discharged) as a proxy.

We examined the distribution and differences of visits by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and geographic region. Our referent age group was 65 to 74 years because this group would likely be the healthiest in this particular older population. We used Medicare’s 6 mutually exclusive race/ethnicity codes: White, Black, Native American, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and other or unknown. To categorize the states, we used the US Census Bureau’s 4 geographic regions. We calculated crude incidence rates and Mantel-Haenszel rate ratios (RRs) to determine potential demographic risk factors. Age adjustments could not be calculated because stratified denominator data were not available. We completed statistical analyses with SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and EPISHEET Version 2011 (developed by Rothman).11

RESULTS

During the 2-year study period, a total of 18 768 hypothermia- and hyperthermia-related health care visits were filed to Medicare. More than half (53%) of the total visits were for hyperthermia, and 47% were for hypothermia. Of the total visits, 73% were by White beneficiaries, and 68% were men.

Most (73%) of the visits were in the outpatient care setting (n = 13 717), and of these, 64% were for hyperthermia. The remaining 27% of the visits were inpatient (n = 5051), of which 63% were for hypothermia.

Hypothermia

We identified 8761 visits for hypothermia, including 359 (4%) that resulted in fatalities. The mortality rate was 0.50 per 100 000 per year. The morbidity rates for inpatient and outpatient visits were 5.29 and 6.93 per 100 000 per year, respectively (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Incidence and Rate Ratios of Hypothermia Inpatient (n = 3792) and Outpatient (n = 4969) Visits Recorded Among Medicare Enrollees: United States, 2004 and 2005

| Inpatienta Visit Rate, Visit/100 000 | RR (95% CI) | P | Outpatientb Visit Rate, Visit/100 000 | RR (95% CI) | P | |

| Annual crude rate | 5.29 | … | … | 6.93 | … | … |

| Age, y | ||||||

| < 65 | 6.19 | 2.95 (2.66, 3.28) | < .001 | 14.82 | 4.26 (3.95, 4.60) | < .001 |

| 65–74 (Ref) | 2.10 | 1.00 | 3.48 | 1.00 | ||

| 75–84 | 5.57 | 2.65 (2.41, 2.92) | < .001 | 5.92 | 1.70 (1.57, 1.85) | < .001 |

| ≥ 85 | 14.92 | 7.11 (6.46, 7.82) | < .001 | 10.24 | 2.95 (2.69, 3.22) | < .001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 5.82 | 1.20 (1.12, 1.28) | < .001 | 9.31 | 1.85 (1.75, 1.96) | < .001 |

| Female (Ref) | 4.84 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White (Ref) | 4.59 | 1.00 | 6.17 | 1.00 | ||

| Black | 12.31 | 2.68 (2.49, 2.90) | < .001 | 13.10 | 2.12 (1.97, 2.28) | < .001 |

| Asian | 1.31 | 0.29 (0.17, 0.47) | < .001 | 2.12 | 0.34 (0.23, 0.51) | < .001 |

| Hispanic | 3.09 | 0.67 (0.51, 0.90) | .006 | 5.28 | 0.85 (0.67, 1.06) | .16 |

| Native American | 10.84 | 2.36 (1.70, 3.28) | < .001 | 36.14 | 5.85 (4.88, 7.02) | < .001 |

| Other | 4.45 | 0.97 (0.74, 1.27) | .825 | 7.44 | 1.21 (0.98, 1.48) | .08 |

| Region (US) | ||||||

| Northeast | 8.19 | 1.80 (1.66, 1.95) | < .001 | 12.09 | 2.68 (2.49, 2.89) | < .001 |

| Midwest | 5.77 | 1.26 (1.16, 1.37) | < .001 | 7.61 | 1.69 (1.56, 1.82) | < .001 |

| South (Ref) | 4.56 | 1.00 | 4.51 | 1.00 | ||

| West | 3.57 | 0.78 (0.70, 0.87) | < .001 | 6.43 | 1.42 (1.30, 1.56) | < .001 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; RR = rate ratio. Denominator population represents fee-for-service hospital insurance or supplementary medical insurance only.

Source. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of Information Services: data from the 100% Denominator File.

Data from Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) database includes inpatient, emergency department (ED) admits, and skilled nursing facilities.

Includes clinic visits and ED visits not resulting in admission.

Age-group differences were seen among the visit types. Compared with the referent age group (65–74 years), the oldest beneficiaries (≥ 85 years) had significantly higher rates of inpatient visits (14.92 per 100 000; RR = 7.11; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 6.46, 7.82; Table 1). By contrast, outpatient visit rates were significantly higher (14.82 per 100 000) for the youngest age group (< 65 years) compared with all age groups. For both visit types, men had significantly higher rates than women, although their outpatient rate was nearly double their inpatient rate (9.31 per 100 000 vs 5.82 per 100 000; Table 1). Significant racial differences also were observed among Black and Native American beneficiaries compared with White beneficiaries, with RRs greater than 2 for both inpatient and outpatient visits (Table 1).

Geographically, the highest rates and RRs were seen in the Northeast and Midwest for inpatient visits (RR = 1.80; 95% CI = 1.66, 1.95 and RR = 1.26; 95% CI = 1.16, 1.37, respectively) as well as outpatient visits (RR = 2.68; 95% CI = 2.49, 2.89 and RR = 1.69; 95% CI = 1.56, 1.82, respectively). The states with the highest annual rates of hypothermia-related visits per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries were Alaska (36.1), Maine (31.3), and Montana (30.4).

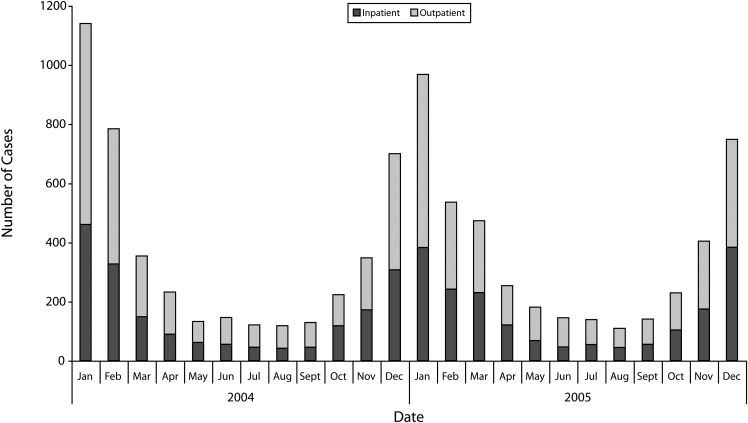

More than half (56%) of the hypothermia-related visits occurred during the winter months (December–February) with January having the highest frequency of visits recorded (Figure 1). Reports of hypothermia-related visits, however, continued year-round, and approximately 100 visits occurred per month, with 14% of the total hypothermia-related visits occurring during May through September.

FIGURE 1—

Frequency of hypothermia-related inpatient and outpatient visits recorded among Medicare enrollees, 2004 and 2005.

The most common diagnosis for hypothermia-related visits was “hypothermia (accidental), excluding hypothermia not associated with low environmental temperature,” ICD-9-CM code 991.6. The second most common diagnosis was frostbite of an extremity, ICD-9-CM codes 991.0 to 991.2.

Hyperthermia

A total of 10 007 visits were for hyperthermia, and of these, 42 (0.42%) resulted in death, corresponding to a mortality rate of 0.06 per 100 000 per year. The hyperthermia outpatient rate was approximately 6 times the rate of inpatient visits (12.20 per 100 000 vs 1.76 per 100 000; Table 2). Rates of visit types also varied by age group, with a significantly higher inpatient rate in the oldest beneficiaries (≥ 85 years) compared with the referent age group (Table 2). An opposite trend was observed for outpatient visits; beneficiaries younger than 65 years had an outpatient visit rate of 21.29 per 100 000 per year, nearly double that for all other age categories (Table 2). The inpatient and outpatient visit rate among men was about 2 times that among women (Table 2). Black beneficiaries had significantly higher RRs for inpatient visits (RR = 1.80; 95% CI = 1.55, 2.09), and Black and Native American patients had significantly higher RRs for outpatient visits (RR = 1.59; 95% CI = 1.50, 1.69 and RR = 2.15; 95% CI = 1.73, 2.67, respectively; Table 2).

TABLE 2—

Incidence and Rate Ratios of Hyperthermia Inpatient (n = 1259) and Outpatient (n = 8748) Visits Recorded Among Medicare Enrollees: United States, 2004 and 2005

| Inpatienta Visit Rate, Visit/100 000 | RR (95% CI) | P | Outpatientb Visit Rate, Visit/100 000 | RR (95% CI) | P | |

| Annual crude rate | 1.76 | … | … | 12.20 | … | … |

| Age, y | ||||||

| < 65 | 1.86 | 1.61 (1.36, 1.90) | < .001 | 21.29 | 2.37 (2.25, 2.50) | < .001 |

| 65–74 (Ref) | 1.16 | 1.00 | 8.96 | 1.00 | ||

| 75–84 | 2.03 | 1.75 (1.52, 2.02) | < .001 | 11.73 | 1.31 (1.24, 1.40) | < .001 |

| ≥ 85 | 3.12 | 2.70 (2.30, 3.17) | < .001 | 11.60 | 1.30 (1.21, 1.40) | < .001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 2.44 | 2.03 (1.81, 2.27) | < .001 | 16.46 | 1.87 (1.79, 1.95) | < .001 |

| Female (Ref) | 1.20 | 1.00 | 8.75 | 1.00 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White (Ref) | 1.64 | 1.00 | 11.62 | 1.00 | ||

| Black | 2.94 | 1.80 (1.55, 2.09) | < .001 | 18.46 | 1.59 (1.50, 1.69) | < .001 |

| Asian | 0.65 | 0.40 (0.20, 0.80) | .01 | 4.09 | 0.35 (0.27, 0.46) | < .001 |

| Hispanic | 1.80 | 1.10 (0.76, 1.60) | .61 | 9.85 | 0.85 (0.72, 0.99) | .04 |

| Native American | 2.71 | 1.66 (0.86, 3.20) | .13 | 25.00 | 2.15 (1.73, 2.67) | < .001 |

| Other | 1.62 | 0.99 (0.64, 1.54) | .96 | 12.38 | 1.07 (0.91, 1.25) | .44 |

| Region (US) | ||||||

| Northeast | 1.42 | 1.00 | 12.56 | 1.00 | ||

| Midwest | 0.77 | 0.55 (0.44, 0.68) | < .001 | 6.64 | 0.53 (0.50, 0.56) | < .001 |

| South (Ref) | 2.84 | 2.00 (1.71, 2.34) | < .001 | 17.86 | 1.42 (1.35, 1.50) | < .001 |

| West | 1.29 | 0.91 (0.73, 1.22) | .372 | 8.34 | 0.66 (0.61, 0.72) | < .001 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; RR = rate ratio. Denominator population represents fee-for-service hospital insurance or supplementary medical insurance only.

Source. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of Information Services: data from the 100% Denominator File.

Data from Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) database includes inpatient, emergency department (ED) admits, and skilled nursing facilities.

Includes clinic visits and ED visits not resulting in admission.

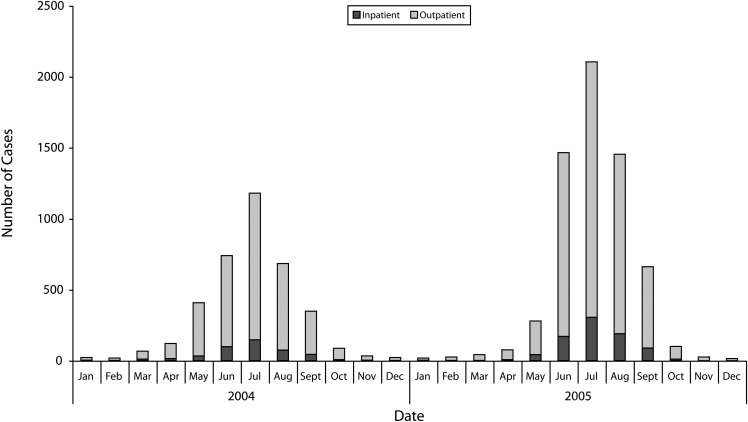

Geographically, the Southern region represented nearly 60% of the total number of hyperthermia-related visits and had the highest rates for both inpatient and outpatient visits (Table 2). The Northeast region rates were elevated, especially for outpatient visits (12.56 per 100 000) compared with the West and Midwest rates (8.34 per 100 000 and 6.64 per 100 000, respectively). The states with the highest annual rates of hyperthermia-related visits per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries were Mississippi (38.2), Louisiana (29.5), and Oklahoma (29.3). Hyperthermia-related visits were highest during the summer months (June–August) for both years, with the number of visits doubling in 2005 (n = 5025) compared with 2004 (n = 2607). During the study period, the peak month for hyperthermia-related visits was July (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2—

Frequency of hyperthermia-related inpatient and outpatient visits recorded among Medicare enrollees, 2004 and 2005.

Most of the hyperthermia-related visits were diagnosed as “heat exhaustion, unspecified,” ICD-9-CM code 992.5. Nearly half of the inpatient admissions were diagnosed as “heat exhaustion, unspecified,” and 38% were diagnosed as “heatstroke and sun stroke,” ICD-9-CM code 992.0.

Emergency Department Hypothermia and Hyperthermia Visits

Of the 18 768 visits in our study, 78% (n = 14 572) involved care in an ED. During 2004 to 2005, 6000 visits were made to the ED for hypothermia, representing a rate of 8.37 per 100 000 per year. Of the hypothermia-related visits to the ED, 55% resulted in inpatient admission. Of these hypothermia-related admissions, 31% were among those older than 85 years, whereas almost half (42%) of the discharged patients were appreciably younger (< 65 years). During 2004 to 2005, 8572 ED visits were made for hyperthermia, representing a rate of 11.96 per 100 000 per year. Of the hyperthermia-related visits to the ED, 11% resulted in inpatient care, whereas 89% were discharged.

Medicare Costs for Hypothermia- and Hyperthermia-Related Visits

Charges submitted to Medicare for direct costs and resource use associated with hypothermia- and hyperthermia-related visits for the study period totaled $134 million. Total annual costs were higher for hypothermia-related visits (nearly $98 million) than for hyperthermia-related visits ($36 million). However, total costs for hyperthermia-related visits more than doubled from $11 million in 2004 to $25 million in 2005.

ICU costs represented 13% to 14% of the total hypothermia cost. The median length of hypothermia hospital stays was nearly 4 days (range = 1–91 days); however, the median length of skilled nursing facility stays was approximately 3 weeks (range = 1–212 days). For hyperthermia visits, the 2005 ICU costs were higher (9% of total costs) than the 2004 ICU costs (6% of total costs). The median length of hyperthermia hospital stays increased from 2 days in 2004 to 3 days in 2005. The median length of hyperthermia-related skilled nursing facility stays also increased in 2005 by 4.5 days (13 days to 17.5 days).

DISCUSSION

Of the nearly 19 000 visits attributed to effects of heat and cold from an environmental etiology, we found more hyperthermia-related visits (n = 10 007) than hypothermia-related visits (n = 8761). A larger proportion of hyperthermia-to-hypothermia burden was recorded in the CDC’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–All Injury Program (NEISS-AIP), a nationally representative sample of 66 hospital EDs. A NEISS-AIP study of visits associated with adverse environmental conditions (e.g., extreme cold or heat, natural disasters) found more ED visits related to heat exposure (78%) than to cold exposure (12%).12 Although our results were in a similar direction, they were not as disparate.

In July 2006, approximately 7 million people younger than 65 years were in the Medicare system. Of these, 6.8 million were disabled without end-stage renal disease, and nearly half were 55 to 64 years old.13 Despite constituting only about 16% of the Medicare population, this age group had the highest rate of outpatient visits for both outcomes. Compared with other beneficiaries, this population (age < 65) had more vulnerabilities including comorbidities (e.g., cognitive or mental impairment), lower income, and less education.14,15

When comparing hypothermia and hyperthermia, our study’s hypothermia-related visits were attributed to more deaths (359 vs 42), higher mortality rates (0.50 per 100 000 vs 0.06 per 100 000), higher inpatient admission rates (5.29 per 100 000 vs 1.76 per 100 000), longer hospital stays (median days = 4 vs 2), and higher health care costs ($98 million vs $36 million).

Hypothermia Discussion

Clearly, these findings of hypothermia being associated with more deaths, higher mortality rates, and more inpatient care compared with hyperthermia indicate the seriousness of cold exposure in older adults. A previous 7-year study of excessive heat and cold in adults older than 60 years that used National Center for Health Statistics data also showed more deaths associated with cold than with heat exposure.2 Our annual hypothermia mortality rate of 0.5 per 100 000 was slightly higher than the rate published by the CDC (0.2–0.4 per 100 000), most likely because our study examined an at-risk subset of the US population, whereas the CDC rates included the entire US population.16,17 The need for specialized health care resources (e.g., ICU) and extended hospital stays (e.g., 4–21 days) led to appreciably higher direct health care costs to Medicare for hypothermia-related visits compared with visits for hyperthermia. These results are consistent with a 1995 to 2004 ED-based study of hypothermia visits from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS).18 These researchers found that older adults with an ED diagnosis of hypothermia were at significantly increased risk for hospitalization (risk ratio = 2.8; 95% CI = 1.8, 4.1) and for the use of an ICU (risk ratio = 6.8; 95% CI = 1.8, 25.0) when compared with all other ED diagnoses assigned to their study population.18

Advanced age, male gender, and Black race/ethnicity are well-documented risk factors for hypothermia-related morbidity and mortality in older adults, and those older than 70 years are most at risk.16–24 Our oldest Medicare beneficiaries (> 85 years) had the highest RR for inpatient visits or admissions associated with hypothermia, which highlights the importance of stratifying age beyond 65 years to better elucidate differences in older adults. Minorities identified as Black and Native American had significantly higher RRs for hypothermia-related inpatient and outpatient visits. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has found such a strong association of risk for environmental hypothermia exposure among Black and Native American older adults.

As in other studies, hypothermia-related visits occurred throughout the year, even in June through August. More than 40% of the cases in NHAMCS study occurred between April and August, and in Ireland, a 6-year study found that 27% of all hypothermia-related hospital admissions and deaths were in April through June.18,24 To better understand why hypothermia occurs throughout the year, future research examining differences between indoor and outdoor hypothermia events in terms of risk factors is warranted. A few studies found that older adults were more likely to be located indoors (e.g., residential facilities, home) than outdoors while becoming hypothermic.25–28 Indoor patients’ risks included sepsis, psychiatric disorders, and living alone. These cases resulted in worse outcomes than did those with outdoor exposure, even in mild climates.25–28 Hypothermia of noninfectious etiology during the summer months could be related to sudden changes of the ambient temperature, exposure to cold water temperatures, and the decreased ability of older or disabled patients to thermoregulate and perceive temperature.26,27 It is important to understand why these events are occurring to develop targeted prevention strategies.

Hyperthermia Discussion

The number of hyperthermia-related visits was greater than the number of hypothermia-related visits, yet because most visits required only outpatient care and were by younger beneficiaries, less severe health outcomes and lower health care costs were found. Beneficiaries younger than 65 years had nearly double the rate of outpatient visits compared with all other age groups. In the aforementioned NEISS-AIP study, persons aged 15 to 44 years recorded the highest hyperthermia-related ED rates.12 However, being an older adult (> 65 years) is a well-established risk factor for heat-related hospitalizations and death.29–31 Other known risk factors are male gender and Black race/ethnicity.29–31 From 1999 to 2003, 40% of heat-related deaths in the United States were among those older than 65 years.32

An update of this analysis with 2004–2005 data found increases in the age-specific crude deaths rates for Blacks and older age groups especially among those > 85 years (CDC, unpublished data, 2008).

Health care use studies of the heat waves in California (2006), Chicago, Illinois (1995), and Missouri (1980) found increases in heat-related ED visits and admissions, especially among older adults.30,33,34 Historically, heat-related studies defined older adults as those older than 65 years, but we further age-stratified up to 85 years and found that those older than 85 years were the most vulnerable age group requiring inpatient care. Minorities, especially Black individuals, were most at risk for hyperthermia visits, which was consistent with results of other heat-related studies.30,34

Interestingly, the number of hyperthermia-related visits and associated health care costs nearly doubled from 2004 to 2005. The likely reason for this finding was that in 2005, above-average warm temperatures were recorded throughout the United States. Specifically, in July 2005, the average temperature throughout the United States was 1.5°F higher than the historical mean, and only 6 states recorded near-average mean temperatures.35 More than 200 cities broke daily high temperature records in 2005. For example, in Denver, Colorado, recorded daily mean temperatures were higher than 105°F in July 2005, equaling an 1878 record.35 The number of beneficiaries who accessed care in 2005 did increase by 500 000, but the access rate per 1000 enrollees remained constant.36 Although we cannot directly associate the July 2005 hyperthermia-related visits with the temperature increases in that month, our data afford us an interesting temporal comparison of visits during a month with “average temperatures” and a month with “extreme temperatures,” which are noticeably different.

Limitations

This study had several important limitations. The denominators used were obtained from the CMS online Medicare and Medicaid Statistical Supplement and lacked the demographic distributions required to calculate adjustments for incidence and risk factors (i.e., age and race).

Medicare race/ethnicity codes for use in statistical analyses are usually limited to Black and White beneficiaries because of the inaccuracies of the other race/ethnicity codes.37,38 A Medicare race/ethnicity validation study compared 900 000 beneficiaries’ self-reported race with their assigned race in the Medicare system and found high sensitivity and agreement for the White and Black participants.37 However, the race coding for Native American beneficiaries had very low sensitivity (35.7%) and agreement (0.45 κ).37 We used data from the Eicheldinger and Bonito37 study in an attempt to correct the Native American race misclassification with a statistical modeling technique called “matrix method” to provide race data estimates; however, this was unsuccessful because of the unstable, sometimes negative estimates reflecting the high proportion of Native American race misclassification in the Medicare data (data not shown). Because of the race misclassification bias in the Medicare data, Native Americans were most likely misrepresented in our data sets, and any important differences found may be erroneous.

Finally, we used only the first primary diagnosis to identify these visits and did not include visits with secondary diagnoses of heat- or cold-related illnesses. We likely underestimated the true burden.

Conclusions

Hypothermia and hyperthermia from environmental exposure are important causes of mortality and morbidity among Medicare beneficiaries and are preventable. We identified 2 vulnerable age groups within the Medicare population—persons younger than 65 years and those older than 85 years—for whom more targeted prevention efforts should be considered. This is a particular concern because of the aging of the US population, the health disparities experienced by the disabled population, and the potential increase in extreme hot and cold weather events associated with climate change. Despite the lower incidence, hypothermia-related visits were more costly in terms of both health effects and health care resources. This finding has implications for caregivers, providers, public health departments, and aging and disability service agencies providing and developing prevention interventions. Health disparities for Black and Native American beneficiaries were found, but for Native American patients, this may have been a result of misclassification bias in our data set.

Further research to better elucidate the circumstances among Medicare beneficiaries, such as risks associated with lack of access to air conditioning or cooling stations, social isolation, exposure to indoor and outdoor cold and hot temperatures, restricted mobility, and comorbidities, should be considered.4,25,28 In conclusion, our findings support the need for public health preparedness agencies to engage their community’s aging and disability services when developing extreme weather response policies to effectively protect the health of these vulnerable populations.39,40

Acknowledgments

Funding support for this study was provided by the National Center for Environmental Health, Division of Environmental Hazards and Health Effects.

We thank Dana Flanders for his valuable contribution to the research and A. Bonito and C. Eicheldinger for providing Medicare race information for the matrix modeling technique. We are grateful to Fuyuen Yip and William Bower for their review of and suggestions on early versions of this article. In addition, we are indebted to Richard Goodman and Margaret J. Moore for their careful review of the article and encouragement to submit this research article to this journal. We would like to distinguish Eduardo Azziz-Baumgartner as the originator of the study design and protocol. We also thank the 3 anonymous reviewers for their constructive critiques.

Human Participant Protection

This study was granted exemption from institutional review board approval at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention because this was an analysis of de-identified, previously collected data.

References

- 1.O’Neill MS, Ebi KL. Temperature extremes and health: impacts of climate variability and change in the United States. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51:13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macey SM, Schneider DF. Deaths from excessive heat and excessive cold among the elderly. Gerontologist. 1993;33:497–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jurkovich GJ. Environmental cold-induced injury. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:247–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajat S, O’Conner M, Kosatsky T. Health effects of hot weather: from awareness of risk factors to effective health protection. Lancet. 2010;375:856–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Confalonieri U, Menne B, Akhtar R . Human health: climate change 2007: impacts, adaption and vulnerability. In: Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, Van der Linden PJ, Hanson CE, eds. Contributions of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007:391–431. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan H, Sengupta M, Velkoff VA, DeBarros KA. Population Reports, 65+ in the United States: 2005. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2005. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2006pubs/p23-209.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2010.

- 7.Social Security Administration. Medicare, 2011. SSA publication 05-10043ICN 460000. Available at: http://www.ssa.gov/pubs/10043.pdf. Accessed September 16, 2011.

- 8. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1980. DHHS publication PHS 80–1260.

- 9.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Statistical Supplement—2007 Edition. Table 2.2b Medicare Enrollment: Hospital Insurance and/or Supplementary Medical Insurance Programs for Total, Fee-for-Service and Managed Care Enrollees, by Demographic Characteristics as of July 1, 2006. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MedicareMedicaidStatSupp/12_2007.asp#TopOfPage. Accessed January 10, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Research Data Assistance Center. How to Identify Emergency Room Services in the Medicare Claims Data. Available at: http://www.resdac.org/Tools/TBs/TN-003_EmergencyRoominClaims_508.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2008.

- 11.Rothman KJ. EPISHEET: spreadsheets for the analysis of epidemiologic data. May 11, 2011. Available at: http://www.epidemiolog.net/studymat. Accessed June 1, 2010

- 12.Sanchez CA, Thomas KE, Malilay J, Annest JL. Nonfatal natural and environmental injuries treated in emergency departments, United States, 2001-2004. Fam Community Health. 2010;33:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Statistical Supplement—2007 Edition. Table 2.3b Hospital Insurance and/or Supplementary Medical Insurance Enrollees, by Demographic Characteristics, Type of Entitlement, Buy-in Status, and Residence, as of July 1, 2006. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MedicareMedicaidStatSupp/12_2007.asp#TopOfPage. Accessed September 14, 2011. [PubMed]

- 14.Cubanski J, Nueman P. Medicare doesn’t work as well for younger, disabled beneficiaries as it does for older enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1725–1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy J, Tuleu IB. Working age Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities: population characteristics and policy considerations. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2007;30:268–291 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Hypothermia-related deaths—Montana, 1999–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:367–368 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Hypothermia-related deaths—United States, 2003–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:173–175 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baumgartner EA, Belson M, Rubin C, Patel M. Hypothermia and other cold-related morbidity emergency department visits: United States, 1995–2004. Wilderness Environ Med. 2008;19:233–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rango N. Exposure-related hypothermia mortality in the United States, 1970-79. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:1159–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spitalnic SJ, Jagminas L, Cox J. An association between snowfall and ED presentation of cardiac arrest. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:572–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Hypothermia-related deaths—Philadelphia, 2001, and United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:86–87 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorjanc ML, Flanders WD, VanDerslice J, Hersh J, Malilay J. Effects of temperature and snowfall on mortality in Pennsylvania. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:1152–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Hypothermia-related deaths—United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:172–173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herity B, Daly L, Bourke GJ, Horgan JM. Hypothermia and mortality and morbidity: an epidemiologic analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1991;45:19–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mégarbane B, Axler O, Chary I, Pompier R, Brivet FG. Hypothermia with indoor exposure is associated with a worse outcome. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1843–1849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor AJ, McGwin G, Davis GG, Brissie RM, Holley TD, Rue LW. Hypothermia deaths in Jefferson County, Alabama. Inj Prev. 2001;7:141–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kempainen RR, Brunette DD. The evaluation and management of accidental hypothermia. Respir Care. 2004;49:192–205 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hajat S, Kovats RS, Lachowycz K. Heat-related and cold-related deaths in England and Wales: who is at risk? Occup Environ Med. 2007;64:93–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basu R. High ambient temperatures and mortality: a review of the epidemiologic studies from 2001 to 2008. Environ Health. 2009;8:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knowlton K, Rotkin-Ellman M, King Get al. The 2006 California heat wave: impacts on hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:61–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Semenza JC, Rubin CH, Falter KHet al. Heat-related deaths during the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Heat-related deaths—United States, 1999–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:796–798 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Semenza JC, McCullough JE, Flanders WD, McGeehin MA, Lumpkin JR. Excess hospital admissions during the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16:269–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones TS, Liang AP, Kilbourne EMet al. Morbidity and mortality associated with the July 1980 heat wave in St. Louis and Kansas City, MO. JAMA. 1982;247:3327–3331 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Climatic Data Center. Climate of 2005: July in Historical Perspective. August 15, 2005. Available at: http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/research/2005/jul/jul05.html. Accessed May 14, 2009.

- 36.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Statistical Supplement—2007 Edition. Table 2.2a Medicare Enrollment: Hospital Insurance and/or Supplementary Medical Insurance Programs for Total, Fee-for-Service and Managed Care Enrollees, by Demographic Characteristics as of July 1, 2005. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MedicareMedicaidStatSupp/12_2007.asp#TopOfPage. Accessed January 10, 2008.

- 37.Eicheldinger C, Bonito A. More accurate racial and ethnic codes for Medicare administrative data. Health Care Financ Rev. 2008;29(3):27–42 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waldo DR. Accuracy and bias of race/ethnicity codes in the Medicare enrollment database. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/HealthCareFinancingReview/downloads/04-05winterpg61.pdf. Accessed September 2, 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Environmental Protection Agency. Excessive Heat Events Guidebook. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/heatisland/about/heatguidebook.html. Accessed February 2, 2009.

- 40.National Organization on Disability. Emergency Preparedness Initiative Guide on the Functional Needs of People With Disabilities—A Guide for Emergency Managers, Planners, and Responders. 2009 ed. Available at: http://www.nod.org/assets/downloads/Guide-Emergency-Planners.pdf. Accessed September 21, 2011.