Abstract

Objectives. We examined population-based smoking trends in Minnesota between 1980 and 2009.

Methods. The Minnesota Heart Survey (MHS) is a population-based, serial, cross-sectional study of cardiovascular risk factor trends among Minneapolis–Saint Paul metropolitan residents. The MHS recently completed its sixth survey (1980–1982 [n = 3799], 1985–1987 [n = 4641], 1990–1992 [n = 5159], 1995–1997 [n = 6690], 2000–2002 [n = 3281], and 2007–2009 [n = 3179]). We used MHS data to examine smoking trends among adults aged 25 to 74 years by means of age-adjusted generalized linear mixed models.

Results. Between 1980 and 2009, the prevalence of current smoking decreased from 32.8% to 15.5% for men and from 32.7% to 12.2% for women (P < .001 for each). Greater decreases occurred among those with higher income and those with more education. Among currently smoking men, the number of cigarettes smoked per day decreased from 26.0 in the 1980–1982 survey to 16.0 in the 2007–2009 survey (P < .001). Similar trends were observed among women.

Conclusions. Although the prevalence of smoking and cigarette consumption decreased from the 1980–1982 period to the 2007–2009 period, interventions specifically designed for those of lower socioeconomic status are needed.

The harmful cardiovascular effects of cigarette smoking are well established, and many interventions have been implemented to reduce the prevalence of smoking. These interventions include those that target individuals, such as the development of new behavioral approaches and smoking-cessation drugs,1–3 as well as population-level interventions, including taxation on cigarettes, stricter advertising laws, increased education, and restricted smoking in public.4–7 Although these interventions have been associated with decreased prevalence of smoking, a substantial subset of the population continues to smoke, and cigarette smoking continues to be an important public health issue. Changes in smoking practices and the identification of those most likely to smoke have important clinical and public health implications. This information is also essential for the design of future smoking-cessation interventions.

Our primary objective was to describe population trends in smoking and smoking practices, such as the quantity of cigarettes smoked and the reported age at smoking initiation, using population-based data from the Minnesota Heart Survey (MHS). Our secondary objective was to examine whether smoking trends varied among those with different demographic characteristics, including age, gender, race, and socioeconomic status (SES).

METHODS

The MHS has been described in detail elsewhere.8–11 Briefly, it is a population-based, serial, cross-sectional study designed to examine trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors. The MHS recently completed its sixth survey (1980–1982, 1985–1987, 1990–1992, 1995–1997, 2000–2002, and 2007–2009) of adults aged 25 to 74 years living in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul Twin Cities metropolitan area.

All MHS surveys used a 2-stage sampling procedure to identify a population-based study sample. In the first stage, the metropolitan area was divided into US Census–defined clusters of approximately 1000 households each. Forty clusters were then randomly selected for the first 3 surveys. Forty-four clusters were selected in the 1995–1997 and 2000–2002 surveys and 47 in the 2007–2009 survey to account for areas of new housing or major population growth. Households were then randomly selected in the second sampling stage. In the 1985–1987 and 1990–1992 surveys, 1 age-eligible individual was randomly selected from each selected household. In the other 4 surveys, all age-eligible individuals of selected households were invited to take part. In the 1995–1997 survey, a small number of clusters were not sampled in the second year of the survey for budgetary reasons; bootstrapping was used to account for unsampled clusters. Each survey included between 3700 and 7000 participants aged 25 to 74 years.

Data Collection

Participants first took part in a home interview where trained interviewers collected data on demographic characteristics, cardiovascular medical history, cardiovascular risk factors, knowledge regarding cardiovascular risk factors, dietary habits, physical activity levels, health insurance coverage, access to a regular physician, self-rated health, smoking practices, and use of cardiovascular medications and dietary supplements. Participants were then invited to take part in a clinic visit. Data collected during the clinic visit included physiological measures such as anthropometric measurements and blood pressures, medical and reproductive history, and detailed questionnaires regarding physical activity and smoking practices. Participants also underwent a nonfasting blood draw to assess serum cholesterol levels. In earlier surveys, smoking measures were biochemically validated with serum thiocyanate, a biomarker of the hydrogen cyanide found in cigarette smoke.12,13 There was high concordance between self-reported and biochemically validated smoking measures9; smoking measures were therefore not biochemically validated in the most recent survey. The present study was restricted to self-reported smoking data.

The proportions of individuals approached who agreed to participate in the home interview of each survey were 91% (1980–1982), 88% (1985–1987), 82% (1990–1992), 83% (1995–1997), 75% (2000–2002), and 64% (2007–2009). The proportions who participated in both the home and clinic components were 69% (1980–1982), 68% (1985–1987), 68% (1990–1992), 65% (1995–1997), 64% (2000–2002), and 56% (2007–2009). We restricted the present study to participants who completed both the home interview and the clinic visit, resulting in 3799, 4641, 5159, 6690, 3281, and 3179 participants in the 6 surveys, respectively.

Smoking Assessment

As part of the home interview, participants were asked, “Have you ever smoked cigarettes on a regular basis, that is, more than 100 cigarettes in your lifetime?” to identify ever smokers and nonsmokers. Those who answered in the affirmative then were asked, “Do you smoke cigarettes at present?” to differentiate between current and past smokers. These data were supplemented by data collected during the clinic visit, where similar questions were asked. Quantities smoked also were assessed. We excluded 39 participants from the analysis because of missing smoking data for both the home interview and the clinic visit. These excluded participants included those with missing “ever-smoking” information (n = 6), those with missing “current smoking” information (n = 18), and those who did not know if they had ever regularly smoked cigarettes (n = 15).

Statistical Analysis

We used generalized linear mixed models to estimate an overall age-adjusted prevalence of current smoking for each survey. These models included the survey as a categorical variable whose fixed effects were estimated with least squares means and a random-effects term to account for clustering by US Census tract–defined neighborhood. We also examined the age-adjusted prevalence of ever smoking. We estimated age-adjusted prevalences for an age of 44.2 years, the mean age in the 1990–1992 survey, except for those of age-specific subgroups, where we used the midpoint of the subgroup. We examined trends in the prevalence of current and ever smoking by using generalized linear mixed models that included time as a continuous variable and a random-effects term to account for clustering by neighborhood. All trend analyses were age-adjusted and stratified by gender unless otherwise indicated. In secondary analyses, we stratified analyses of trends in current smoking by self-reported demographic characteristics (age, race/ethnicity, marital status), variables related to SES (income, level of education), access to medical care (having medical insurance or a regular doctor), and living with another smoker. We included interaction terms in generalized linear mixed models to determine whether trends differed by subgroup. We modeled interactions using time as a continuous variable and assessed them with 1-degree-of-freedom tests. Interactions examined included age × time interactions, representing the presence of birth cohort effects.14

In addition, we assessed trends in mean number of cigarettes smoked per day by using age-adjusted, gender-specific generalized linear mixed models. We restricted these analyses to current smokers. Because the distribution of cigarettes smoked per day was skewed, we used a natural log (ln) transformation to satisfy model assumptions. We then exponentiated survey-specific ln (cigarettes smoked per day) estimates to obtain the age-adjusted mean number of cigarettes smoked per day in each survey.

We also examined trends in smokers' reported age at which they had started smoking regularly. The distribution of age at smoking initiation also was slightly skewed. To facilitate the interpretation of results, we did not transform the dependent variable, but we conducted sensitivity analyses in which we restricted the distribution to values that were normally distributed (ages 14–22 years) as well as to values that were most likely to occur (ages 8–35 years). We also conducted sensitivity analyses that were stratified by past and current smoking status. All analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Approximately 54% of participants taking part in the 6 MHS surveys were female, and the majority of participants were White (Table 1). The median age of participants increased across surveys, from 40.4 years in the 1980–1982 survey to 48.3 years in the 2007–2009 survey. The participants were well educated, with most having at least graduated from high school; the proportion of participants graduating from college or obtaining degrees beyond college education increased across surveys. Of those who answered questions regarding access to care, more than 90% reported having health insurance, and the proportion having a regular physician ranged from 69.0% in the 1990–1992 survey to 78.6% in the 2007–2009 survey.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Population-Based Sample of Adults Aged 25–74 Years: Minnesota Heart Survey, 1980–2009

| Survey |

||||||

| Characteristic | 1980–1982 (n = 3799) | 1985–1987 (n = 4641) | 1990–1992 (n = 5159) | 1995–1997 (n = 6690)a | 2000–2002 (n = 3281) | 2007–2009 (n = 3179) |

| Men, no. (%) | 1761 (46.4) | 2220 (47.8) | 2388 (46.3) | 3071 (45.9) | 1537 (46.8) | 1467 (46.1) |

| Age | ||||||

| Median, y (IQR) | 40.4 (31.7–53.4) | 41.0 (32.5–53.3) | 41.6 (32.7–53.3) | 43.6 (34.8–54.1) | 45.0 (36.6–54.6) | 48.3 (39.5–58.2) |

| Missing, no. (%) | 1 (0.03) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 (0.3) |

| Race/ethnicity, no. (%) | ||||||

| White | 3635 (95.7) | 4450 (95.9) | 4879 (94.6) | 6268 (93.7) | 2948 (89.9) | 2849 (89.6) |

| Black | 104 (2.7) | 101 (2.2) | 150 (2.9) | 167 (2.5) | 121 (3.7) | 102 (3.2) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 17 (0.4) | 32 (0.7) | 59 (1.1) | 81 (1.2) | 73 (2.2) | 97 (3.1) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 17 (0.4) | 22 (0.5) | 20 (0.4) | 39 (0.6) | 38 (1.2) | 22 (0.7) |

| Hispanic | 13 (0.3) | 25 (0.5) | 35 (0.7) | 61 (0.9) | 57 (1.7) | 69 (2.2) |

| Other | 1 (0.03) | 11 (0.2) | 16 (0.3) | 34 (0.5) | 3 (1.7) | 35 (1.1) |

| Missing | 12 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 40 (0.6) | 39 (1.2) | 5 (0.2) |

| Marital status, no. (%) | ||||||

| Married | 2840 (74.8) | 3163 (68.2) | 3291 (63.8) | 3893 (58.2) | 2109 (64.3) | 2347 (73.8) |

| Separated | 57 (1.5) | 110 (2.4) | 125 (2.4) | 47 (0.7) | 35 (1.1) | 40 (1.3) |

| Divorced | 328 (8.6) | 522 (11.2) | 708 (13.7) | 469 (7.0) | 279 (8.5) | 300 (9.4) |

| Widowed | 200 (5.3) | 248 (5.3) | 257 (5.0) | 178 (2.7) | 80 (2.4) | 58 (1.8) |

| Never married | 373 (9.8) | 593 (12.8) | 776 (15.0) | 498 (7.4) | 318 (9.7) | 270 (8.5) |

| Cohabiting | 0 | 0 | 0 | 227 (3.4) | 149 (4.5) | 159 (5.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.03) | 5 (0.1) | 2 (0.04) | 1378 (20.6)b | 311 (9.5)b | 5 (0.2) |

| Level of education, no. (%) | ||||||

| Did not complete high school | 473 (12.5) | 330 (7.1) | 279 (5.4) | 262 (3.9) | 119 (3.6) | 72 (2.3) |

| High school graduate | 1236 (32.5) | 1333 (28.7) | 1378 (26.7) | 1606 (24.0) | 697 (21.2) | 508 (16.0) |

| Vocation or business school | 376 (9.9) | 500 (10.8) | 569 (11.0) | 770 (11.5) | 387 (11.8) | 355 (11.2) |

| Some college but no degree | 725 (19.1) | 1013 (21.8) | 1145 (22.2) | 1368 (20.4) | 609 (18.6) | 569 (17.9) |

| College graduate | 694 (18.3) | 1062 (22.9) | 1263 (24.5) | 1906 (28.5) | 1033 (31.5) | 1102 (34.7) |

| Degree beyond college education | 294 (7.7) | 403 (8.7) | 525 (10.2) | 777 (11.6) | 431 (13.1) | 562 (17.7) |

| Missing | 1 (0.02) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) | 5 (0.2) | 11 (0.3) |

| Annual household income, $, no. (%) | ||||||

| < 20 000 | 1179 (31.0) | 913 (19.7) | 785 (15.2) | 507 (7.6) | 185 (5.6) | 149 (4.7) |

| 20 000–39 999 | 1823 (48.0) | 1801 (38.8) | 1619 (31.4) | 1506 (22.5) | 484 (14.8) | 287 (9.0) |

| 40 000–54 999 | 582 (15.3) | 1829 (39.4) | 1080 (20.9) | 1257 (18.8) | 506 (15.4) | 330 (10.4) |

| ≥ 55 000 | …c | …c | 1365 (26.5) | 3153 (47.1) | 1892 (57.7) | 593 (18.7) |

| Didn't know or refused to answer | 210 (5.5) | 97 (2.1) | 305 (5.9) | 173 (2.6) | 204 (6.2) | 1784 (56.1)d |

| Missing | 5 (0.1) | 1 (0.02) | 5 (0.1) | 94 (1.4) | 10 (0.3) | 36 (1.1) |

| Had health insurance, no. (%)e | ||||||

| Yes | … | … | 4832 (93.7) | 5059 (75.6) | 2848 (86.8) | 3003 (94.5) |

| No | … | … | 325 (6.3) | 249 (3.7) | 124 (3.8) | 175 (5.5) |

| Didn't know | … | … | 2 (0.04) | 2 (0.03) | 1 (0.03) | 0 |

| Missing | … | … | 0 | 1380 (20.6)b | 308 (9.4)b | 1 (0.03) |

| Had regular physician, no. (%)e | ||||||

| Yes | … | … | 3559 (69.0) | 3938 (58.9) | 2273 (69.3) | 2504 (78.8) |

| No | … | … | 1593 (30.9) | 1369 (20.5) | 692 (21.1) | 666 (21.0) |

| Didn't know | … | … | 6 (0.1) | 5 (0.07) | 6 (0.2) | 6 (0.2) |

| Missing | … | … | 1 (0.02) | 1378 (20.6)b | 310 (9.4)b | 4 (0.1) |

| Lived with a smoker, no. (%)e | ||||||

| Yes | … | … | … | … | 550 (16.8) | 399 (12.6) |

| No | … | … | … | … | 2414 (73.6) | 2767 (87.0) |

| Didn't know | … | … | … | … | 7 (0.2) | 7 (0.2) |

| Missing | … | … | … | … | 310 (9.4)b | 6 (0.2) |

Note. IQR = interquartile range. Ellipses indicate data not collected.

In the 1995–1997 survey, a small number of clusters were not sampled in the second year. Bootstrapping was used to account for these missing clusters.

In the 1995–1997 and 2000–2002 surveys, approximately 20% of participants were not interviewed at home but completed an abridged home interview questionnaire either by mail or at the beginning of their clinic visit. In the other 4 surveys, all participants completed the home interview. The abridged questionnaire did not include questions regarding marital status, health insurance, having a regular physician, or living with a smoker.

In the 1980–1982 and 1985–1987 surveys, the highest household income category was ≥ $50 000. Additional household income categories were included in subsequent surveys.

Among those who did not know or refused to answer the question regarding income in the 2007–2009 survey, the vast majority were well educated, with 42% having graduated from college and 24% having a degree beyond college education. We therefore presume that these were participants with high income.

Information regarding having health insurance and a regular physician was collected in the last 4 surveys. Information regarding living with a smoker was collected in the 2 most recent surveys.

Prevalence of Ever Smoking

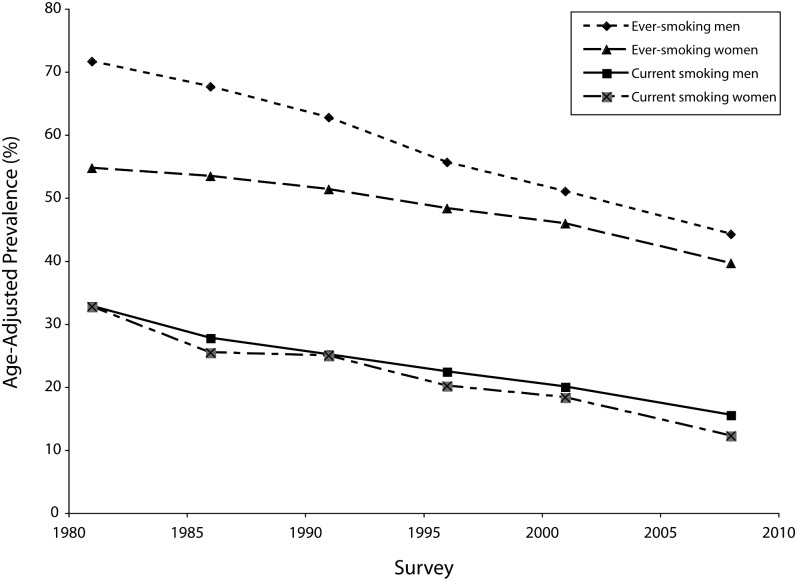

The prevalence of ever smoking decreased between 1980 and 2009 (Figure 1). In the 1980–1982 survey, the prevalence of ever smoking was 71.6% for men and 54.7% for women. By the 2007–2009 survey, the prevalence of ever smoking had decreased to 44.2% for men and 39.6% for women, representing absolute decreases of 27.4 percentage points and 15.1 percentage points across the 6 surveys, respectively (P < .001 for both).

FIGURE 1.

Age-adjusted trends in current and ever smoking: Minnesota Heart Survey, 1980–2009.

Note. All P < .001.

Within each survey, the prevalence of ever smoking increased with age for both men and women (P < .001 for both) (Appendix 1, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Among women, there was an interaction between age and time, indicating that the prevalence of ever smoking was affected by birth cohort effects (P < .001). The prevalence of ever smoking was not affected by birth cohort effects among men (P = .25).

Prevalence of Current Smoking

The overall age-adjusted prevalence of current smoking also decreased across surveys (1980–1982, 32.5%; 1985–1987, 26.4%; 1990–1992, 24.9%; 1995–1997, 21.1%; 2000–2002, 19.1%; 2007–2009, 13.8%; P < .001). Similar decreases were observed among both men and women, with the prevalence decreasing from 32.8% to 15.5% for men and from 32.7% to 12.2% for women between 1980 and 2009 (P < .001 for each) (Table 2). The prevalence of current smoking decreased in almost all subgroups. Among both male and female participants, we observed greater decreases among those who were married or cohabiting, those with more education, and those with higher household incomes. In addition, we observed greater decreases among men who were not living with a smoker and among female participants who reported having a regular physician. After further adjustment for income, we found that the differences in smoking trends among women with and without a regular physician were slightly attenuated.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of Current Smoking Among Men and Women Aged 25–74 Years: Minnesota Heart Survey, 1980–2009

| Prevalence of Characteristic, Range Across Surveys, %a | Age-Adjusted Prevalence of Current Smoking by Survey, %b |

Trend Analysis |

|||||||

| Characteristic | 1980–1982 | 1985–1987 | 1990–1992 | 1995–1997c | 2000–2002 | 2007–2009 | P for Trend | P for Time-Characteristic Interaction | |

| Male participants | |||||||||

| All men | 100 | 32.8 | 27.7 | 25.1 | 22.4 | 20.0 | 15.5 | < .001 | .2d |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White/Asian/Pacific Islander | 91.9–96.9 | 32.6 | 27.0 | 24.2 | 21.6 | 18.3 | 14.8 | < .001 | .88 |

| Other | 3.1–8.1 | 38.9 | 38.3 | 40.6 | 27.4 | 32.5 | 18.1 | .001 | |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married or cohabiting | 68.0–82.1 | 31.9 | 24.2 | 21.9 | 17.8 | 16.4 | 11.2 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Other | 17.9–32.0 | 39.7 | 38.4 | 32.4 | 34.6 | 25.2 | 30.5 | < .001 | |

| Level of education | |||||||||

| > high school graduate | 61.3–82.3 | 29.0 | 23.0 | 19.8 | 16.7 | 15.4 | 11.3 | < .001 | < .001 |

| ≤ high school graduate | 17.7–38.7 | 42.0 | 40.2 | 39.7 | 39.5 | 34.7 | 30.6 | .002 | |

| Household incomee | |||||||||

| Above survey-specific median | 55.8–60.6 | 29.0 | 23.0 | 19.5 | 17.0 | 12.5 | 17.2 | < .001 | .002 |

| Below survey-specific median | 39.4–44.2 | 37.7 | 32.0 | 30.2 | 27.6 | 27.7 | 30.2 | < .001 | |

| Had health insurancef | |||||||||

| Yes | 92.1–94.8 | … | … | 23.1 | 19.3 | 16.7 | 13.0 | < .001 | .19 |

| No | 5.2–7.9 | … | … | 47.4 | 56.6 | 48.4 | 38.9 | .16 | |

| Had regular physicianf | |||||||||

| Yes | 61.3–72.0 | … | … | 22.6 | 18.1 | 16.0 | 12.1 | < .001 | .2 |

| No | 28.0–38.7 | … | … | 29.8 | 27.3 | 23.6 | 21.6 | < .001 | |

| Lived with a smokerf | |||||||||

| Yes | 11.8–19.2 | … | … | … | … | 40.6 | 47.8 | .16 | .05 |

| No | 80.8–88.2 | … | … | … | … | 11.8 | 9.2 | .045 | |

| Female participants | |||||||||

| All women | 100 | 32.7 | 25.4 | 24.9 | 20.1 | 18.3 | 12.2 | < .001 | .2d |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White/Asian/Pacific Islander | 92.5–96.3 | 32.4 | 24.7 | 24.2 | 19.1 | 17.2 | 11.9 | < .001 | .42 |

| Other | 3.9–7.5 | 33.7 | 32.4 | 29.3 | 29.5 | 24.0 | 11.2 | < .001 | |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married or cohabiting | 60.2–76.2 | 30.3 | 20.7 | 20.4 | 15.8 | 14.6 | 9.9 | < .001 | .05 |

| Other | 23.8–39.8 | 39.7 | 33.3 | 30.8 | 27.0 | 24.7 | 18.0 | < .001 | |

| Level of education | |||||||||

| > High school graduate | 49.6–81.1 | 28.4 | 20.5 | 19.9 | 15.9 | 14.8 | 9.8 | < .001 | .001 |

| ≤ High school graduate | 18.9–50.4 | 38.7 | 34.9 | 35.9 | 32.0 | 28.9 | 23.2 | < .001 | |

| Household incomee | |||||||||

| Above survey-specific median | 43.6–53.8 | 30.6 | 21.4 | 18.9 | 14.6 | 11.9 | 13.0 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Below survey-specific median | 46.2–56.4 | 35.3 | 28.3 | 29.1 | 25.3 | 23.1 | 19.6 | < .001 | |

| Had health insurancef | |||||||||

| Yes | 95.1–96.7 | … | … | 23.6 | 18.3 | 17.2 | 11.9 | < .001 | .32 |

| No | 3.3–4.9 | … | … | 44.1 | 33.7 | 37.8 | 17.3 | < .001 | |

| Had regular physicianf | |||||||||

| Yes | 75.8–85.1 | … | … | 24.6 | 17.9 | 16.5 | 10.7 | < .001 | .002 |

| No | 14.9–24.2 | … | … | 25.5 | 24.6 | 25.6 | 18.8 | .07 | |

| Lived with a smokerf | |||||||||

| Yes | 13.3–17.9 | … | … | … | … | 40.5 | 36.7 | .41 | .3 |

| No | 82.1–86.7 | … | … | … | … | 11.8 | 7.6 | < .001 | |

Note. Ellipses indicate data not collected.

Excludes those with missing data.

All age-adjusted analyses were adjusted to the mean age on the 1990–1992 survey (44.2 y).

In the 1995–1997 survey, a small no. of clusters were not sampled in the second y. Bootstrapping was used to account for these missing clusters.

This analysis was conducted with all participants. All other interactions were examined in gender-specific analyses. Interactions were modeled using product terms, with time as a continuous variable, and were assessed with 1 df tests.

In the 1980–1982 and 1985–1987 surveys, the highest household income category was ≥ $50 000. Additional household income categories were included in subsequent surveys. Data were dichotomized at the survey-specific median category. Because categories were used, the prevalence may exceed 50%.

Information regarding having health insurance and a regular physician was collected in the last 4 surveys. Information regarding living with a smoker was collected in the 2 most recent surveys.

In all surveys, the prevalence of current smoking decreased with increasing age for both men and women (P < .001 for each; Appendix 2, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). There was no evidence of birth cohort effects for men (P = .55) or women (P = .63).

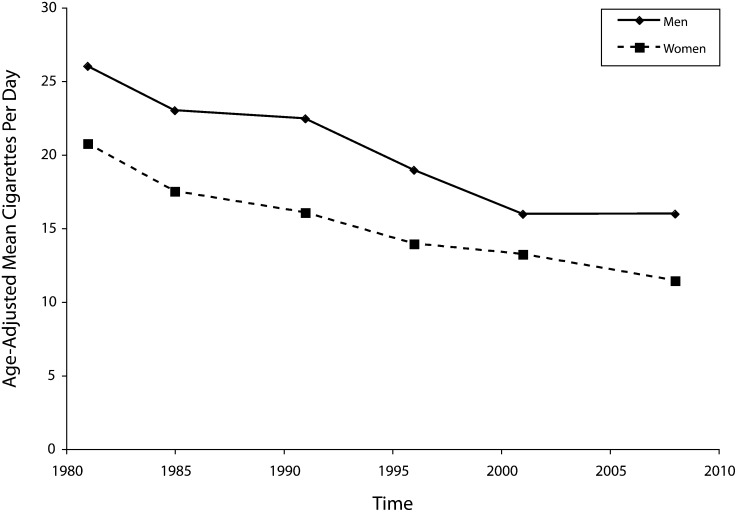

Cigarettes Smoked per Day

Among current smokers, the reported number of cigarettes smoked per day decreased substantially across the 6 surveys (Figure 2). In the 1980–1982 survey, the age-adjusted number of cigarettes smoked per day was 26.0 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 23.2, 29.2) among men and 20.8 (95% CI = 18.7, 23.0) among women. By the 2007–2009 survey, this figure had dropped to 16.0 (95% CI = 13.9, 18.4) and 11.4 (95% CI = 10.0, 13.1) cigarettes smoked per day, respectively (P < .001 for both).

FIGURE 2.

Age-adjusted trends in cigarettes smoked per day among current smokers: Minnesota Heart Survey, 1980–2009.

Note. All P < .001.

Age at Smoking Initiation

Across surveys, male ever smokers reported that they had started smoking regularly when aged approximately 17.7 years (change per 5 years of calendar time = −0.02; 95% CI = −0.10, 0.06; Appendix 3, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). We obtained similar results for both current and past male smokers (data not shown). By contrast, the age at which female ever smokers had started smoking regularly decreased across surveys. In the 1980–1982 survey, the mean age at which women had started smoking was 19.4 years (95% CI = 18.9, 19.8). By the 2007–2009 survey, however, women's reported age at smoking initiation had decreased to 17.7 years (95% CI = 17.3, 18.0), representing a decrease of 0.38 years (95% CI = −0.47, −0.30) per 5 years of calendar time. We obtained similar results for both current and past smokers, although trends were slightly attenuated among female past smokers (change per 5 years of calendar time = −0.26; 95% CI = −0.40, −0.11). In addition, although there were differences by gender in earlier surveys, ever-smoking men and women had started smoking at similar ages in the most recent survey.

Reported age at smoking initiation also varied with participants' age. Among ever-smoking women, older participants reported an older age at initiation than their younger counterparts (P < .001). Among ever-smoking men, this age effect was present (P = .06) but not clinically important (Appendix 3).

We conducted sensitivity analyses that were restricted to participants who had started smoking between the ages of (1) 8 and 35 years and (2) 14 and 22 years. Trends for the age at which male and female ever smokers started smoking regularly were consistent with those in our primary, unrestricted analyses (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our study was designed to describe population-based trends in cigarette smoking and smoking-related behaviors among adults aged 25 to 74 years. We found that between 1980 and 2009 there was a substantial decrease in the prevalence of ever and current smoking. The prevalence of current smoking decreased among both men and women and in most subgroups. However, these trends were attenuated among those of lower education and lower income, 2 markers of lower SES; these participants also had higher smoking prevalences in each of the 6 surveys.

Our results suggest that interventions implemented during the last 3 decades have been effective at decreasing the prevalence of smoking, by increasing both the proportion of participants who have never smoked and the proportion of those who smoked regularly at one time but no longer do so. These interventions include the development of smoking-cessation drugs (such as nicotine replacement therapies, bupropion, and varenicline) and improved behavioral smoking-cessation therapies. In addition, broad societal interventions have been implemented during the last 30 years, including increased taxation at both the state15 and federal levels,16 legislation limiting smoking in public places such as Minnesota's Freedom to Breathe Act,17 and the development of antismoking programs specific to Minnesota that were funded as part of the Tobacco Settlement. ClearWay Minnesota is a nonprofit tobacco control organization that has increased public awareness of the harmful effects of cigarettes through advertising, funded research, and community development grants; ClearWay Minnesota has also provided smoking-cessation services (e.g., counseling, medication, workplace support) free of charge to Minnesotans.18,19 At the same time, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota used part of their settlement funds to establish Prevention Minnesota, whose goals are to decrease tobacco use, heart disease, and preventable cancers through individual and community health interventions.20

These implemented interventions also likely contributed to the observed 40% decrease in age-adjusted cigarette consumption among those who continued to smoke. It is possible that the participants with high levels of nicotine dependence have reduced their consumption rather than quitting or that this reduction represents the first step in the quitting process. It also is possible that smokers believe that decreasing their consumption may reduce the harmful effects of smoking or that smokers are maximizing their exposure by fully smoking cigarettes. Further research is required to definitively explain the observed reduction in cigarette consumption.

Interventions implemented during the study period may not be as effective among all participants. For example, Niederdeppe et al. compared the effectiveness of smoking-cessation media campaigns by income level and level of education.21 They found that “keep trying to quit” campaigns were less effective among less-educated participants but that the effectiveness of these campaigns was not affected by income. These results for education were consistent with our finding of an attenuated decrease in smoking among less-educated participants. These results are also consistent with the work of Frohlich and Potvin, who argue that socially disadvantaged populations are less likely to adopt population-based interventions.22

Our finding that the age at which female participants had started smoking regularly decreased across surveys is of public health importance. Between 1980 and 2009, the mean age at which female participants started smoking decreased by approximately 2 years. This decrease is likely explained, at least in part, by advertising directed at youths. This advertising, which was greatly restricted in Minnesota by the Minnesota Tobacco Settlement5 and in 46 states by the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement between the National Association of Attorneys General and the tobacco industry,23 has been described in detail elsewhere.24 Recently, Pierce et al. used data from a national cohort of 1036 adolescents to examine cigarette-advertising campaigns targeting teenagers.25 Male participants' favorite brand of cigarettes remained stable across the 5 telephone surveys (2003–2008); however, female participants' favorite brand changed dramatically after the Camel No. 9 advertising campaign, a fashion-themed campaign that took place in 2007.

In June 2010, the Food and Drug Administration implemented a new rule titled “Regulations Restricting the Sale and Distribution of Cigarettes and Smokeless Tobacco to Protect Children and Adolescents” that further restricts the sale and promotion of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco to minors.7 Nonetheless, the results of the study by Pierce et al. and our findings highlight the need for continued vigilance regarding advertising directed at youths as well as additional research into why young women are smoking regularly at an increasingly younger age.

Our results also highlight the important effects of age and birth cohorts on the prevalence of smoking. The prevalence of current smoking decreases with increasing age across all surveys, an observation that is likely attributable to a combination of true age effects and selective mortality among smokers. These results, combined with our finding that the reported age at which women started to smoke decreased across surveys, underscore the importance of targeting younger smokers in future smoking abstinence campaigns. In contrast, ever smoking among women was affected by birth cohort. Older women in earlier surveys had a substantially lower prevalence of ever smoking than men of a similar age, presumably because of differing social norms present during the early part of the 20th century. These gender differences were not present in more recent birth cohorts.

The prevalence and trends of smoking in the United States have been examined previously.26,27 Using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Health Interview Survey, Schoenborn and Adams reported that the age-adjusted prevalence of current smoking among US adults was 20.4% between 2005 and 2007, with men more likely to smoke than women (23.0% vs 18.0%).26 The prevalence and trends of smoking were also examined in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS),27 a population-based telephone surveillance system. BRFSS data suggest that the prevalence of smoking decreased steadily between 1995 and 2008 both in Minnesota (17.4% smoked every day in 1995 vs 12.1% in 2008) and the United States as a whole (19.9% vs 13.4%). Our estimated prevalences are lower than those reported by Schoenborn and Adams, probably because of their inclusion of adults aged 18 to 24 years, the age group in whom the prevalence was the greatest,26 and lower prevalence of current smoking in Minnesota than in the rest of the United States. Possible sources of variability between MHS and BRFSS smoking prevalences include variations in the response rates and questions posed and the limitations of telephone-based surveys.28

The decreasing trends in cigarettes smoked per day in Minnesota are consistent with previously reported trends.5,29–33 Using 1976–2003 data from the Nurses' Health Study, Sarna et al.32 found that the mean number of cigarettes smoked per day was greatest in 1986 and declined by 4 to 5 cigarettes per day between 1986 and the period 2002 to 2003. Similarly, Al-Delaimy et al. used data from the Tobacco Use Supplements of the Current Population Survey to examine cigarettes smoked per day among non-Hispanic White daily smokers in California, New York–New Jersey, and tobacco-growing states.29 They found a decline in mean number of cigarettes smoked per day between 1992 and 2002 in all groups of states; this decline was present in all age groups except those aged 50 to 64 years living in tobacco-growing states. Using the California Tobacco Survey, Gilpin et al. obtained similar results.33

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has a number of strengths. First, our population-based sample provides a representative picture of smoking practices among adults aged 25 to 74 years living in the Twin Cities metropolitan area. Second, similar sampling and measurement methods were used throughout the 6 surveys; this consistency ensures that the observed trends reflect true shifts in smoking practices during the study period.

There also are some potential limitations. First, we excluded individuals aged 18 to 24 years from the present study because of the itinerant nature of this population and the complexity of sampling university residences. Second, although this study involved a population-based sample of the Minneapolis–Saint Paul Twin Cities metropolitan area, the generalizability of its results to other metropolitan areas or rural areas is unknown. Third, the response rate decreased with each survey, and data suggest that older individuals were more likely to participate in the more recent surveys than were their younger counterparts. The median age of participants increased by 6.7 years between the 1990–1992 and 2007–2009 surveys. During this time, the median age in Minnesota increased by only 4.9 years.34,35 Our analyses were adjusted by age to account for potential confounding. Nonetheless, differential participation remains a potential limitation.

Fourth, smokers were less likely to attend clinic visits than nonsmokers.9 However, restricting the study to those who attended clinic visits provided more conservative estimates of smoking trends. Finally, we relied on self-reported smoking habits, and it is possible that some participants may have underreported smoking for reasons of social desirability. We believe that participants in a population-based survey are less likely to underreport smoking than participants in smoking-cessation clinical trials, who are under greater pressure to be abstinent. Furthermore, data from earlier surveys9 showed high concordance between self-reported and biochemically validated smoking measures, suggesting that our use of self-reported smoking status is a valid approach.

Conclusions

The prevalence of current cigarette smoking decreased dramatically between 1980 and 2009. This decrease was observed among both men and women and in almost all subgroups examined. However, the downward trend was less pronounced among participants with lower SES as defined by household income and level of education attained. The decreased prevalence of smoking was accompanied by an approximately 40% reduction in the number of cigarettes smoked among those who continued smoking. Although the combined interventions implemented during the study period in our region are associated with decreased overall prevalence of smoking and cigarette consumption, interventions specifically designed for those of lower SES are needed.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute titled “Minnesota Heart Survey—Renewal” (grant R01-HL023727). K. B. Filion is supported in part by postdoctoral fellowships from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and Les Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (Quebec Foundation for Health Research).

We thank Summer Zhou for her programming support.

Human Participant Protection

The Minnesota Heart Survey was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Minnesota. All participants provided informed consent.

References

- 1.Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A US Public Health Service report. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):158–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg MJ, Filion KB, Yavin D, et al. Pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ. 2008;179(2):135–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mottillo S, Filion KB, Belisle P, et al. Behavioural interventions for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(6):718–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali MK, Koplan JP. Promoting health through tobacco taxation. JAMA. 2010;303(4):357–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurt RD, Ebbert JO, Muggli ME, Lockhart NJ, Robertson CR. Open doorway to truth: legacy of the Minnesota Tobacco Trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(5):446–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein EG, Forster JL, Erickson DJ, Lytle LA, Schillo B. The relationship between local clean indoor air policies and smoking behaviours in Minnesota youth. Tob Control. 2009;18(2):132–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Food and Drug Administration Regulations restricting the sale and distribution of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/ProtectingKidsfromTobacco/RegsRestrictingSale/default.htm. Accessed August 17, 2010

- 8.Arnett DK, McGovern PG, Jacobs DR, Jr, et al. Fifteen-year trends in cardiovascular risk factors (1980–1982 through 1995–1997): the Minnesota Heart Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(10):929–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duval S, Jacobs DR, Jr, Barber C, et al. Trends in cigarette smoking: the Minnesota Heart Survey, 1980–1982 through 2000–2002. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(5):827–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S, Harnack L, Jacobs DR, Jr, Steffen LM, Luepker RV, Arnett DK. Trends in diet quality for coronary heart disease prevention between 1980–1982 and 2000–2002: the Minnesota Heart Survey. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(2):213–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steffen LM, Arnett DK, Blackburn H, et al. Population trends in leisure-time physical activity: Minnesota Heart Survey, 1980–2000. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(10):1716–1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS, Snow MG. Assessing outcome in smoking cessation studies. Psychol Bull. 1992;111(1):23–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galanti LM. Specificity of salivary thiocyanate as marker of cigarette smoking is not affected by alimentary sources. Clin Chem. 1997;43(1):184–185 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs DR, Jr, Hannan PJ, Wallace D, Liu K, Williams OD, Lewis CE. Interpreting age, period and cohort effects in plasma lipids and serum insulin using repeated measures regression analysis: the CARDIA Study. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):655–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids State cigarette tax rates & rank, date of last increase, annual pack sales & revenues, and related data. Available at: http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/research/factsheets/pdf/0099.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2010

- 16.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids The erosion of federal cigarette taxes over time. Available at: http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/research/factsheets/pdf/0093.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2011

- 17.Minnesota Department of Health Freedom to breathe. Available at: http://health.state.mn.us/freedomtobreathe. Accessed October 12, 2010

- 18.ClearWay Minnesota About QUITPLAN services. Available at: http://www.clearwaymn.org/index.asp?Type=B_BASIC&SEC={4C946EB5-70AD-41F8-831E-C53E62FB3FE2}. Accessed October 14, 2010

- 19.ClearWay Minnesota Our history. Available at: http://www.clearwaymn.org/index.asp?Type=B_BASIC&SEC={203FDB04-37A3-4BFD-8E6F-39CEE840B399}. Accessed October 12, 2010

- 20.Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota Prevention Minnesota. Available at: http://www.preventionminnesota.com. Accessed December 7, 2010

- 21.Niederdeppe J, Fiore MC, Baker TB, Smith SS. Smoking-cessation media campaigns and their effectiveness among socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged populations. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(5):916–924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(2):216–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Association of Attorneys General Master settlement agreement. Available at: www.ag.ca.gov/tobacco/pdf/1msa.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2010

- 24.Lovato C, Linn G, Stead LF, Best A. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003; (4):CD003439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierce JP, Messer K, James LE, et al. Camel No. 9 cigarette-marketing campaign targeted young teenage girls. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):619–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoenborn CA, Adams PF, National Center for Health Statistics. Health behaviors of adults: United States, 2005–2007. Vital Health Stat 10. 2010;(245):1–132 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey data, 1995–2008. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.htm. Accessed April 1, 2010

- 28.Kempf AM, Remington PL. New challenges for telephone survey research in the twenty-first century. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:113–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Delaimy WK, Pierce JP, Messer K, White MM, Trinidad DR, Gilpin EA. The California Tobacco Control Program's effect on adult smokers, 2: daily cigarette consumption levels. Tob Control. 2007;16(2):91–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Faou AL, Baha M, Rodon N, Lagrue G, Menard J. Trends in the profile of smokers registered in a national database from 2001 to 2006: changes in smoking habits. Public Health. 2009;123(1):6–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monteiro CA, Cavalcante TM, Moura EC, Claro RM, Szwarcwald CL. Population-based evidence of a strong decline in the prevalence of smokers in Brazil (1989–2003). Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(7):527–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarna L, Bialous SA, Jun HJ, Wewers ME, Cooley ME, Feskanich D. Smoking trends in the Nurses' Health Study (1976–2003). Nurs Res. 2008;57(6):374–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilpin EA, Messer K, White MM, Pierce JP. What contributed to the major decline in per capita cigarette consumption during California's comprehensive tobacco control programme? Tob Control. 2006;15(4):308–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minnesota Department of Administration Census 2000: Minnesota age profile. Available at: http://www.demography.state.mn.us/Cen2000profiles/cen00profage.html. Accessed July 26, 2010

- 35.US Census Bureau GCT-T2-R. Median age of the total population. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/GCTTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-_box_head_nbr=GCT-T2-R&-ds_name=PEP_2008_EST&-format=U-40Sa. Accessed July 26, 2010