Abstract

Objectives. We examined how US cultural involvement related to suicide attempts among youths in the Dominican Republic.

Methods. We analyzed data from a nationally representative sample of youths attending high school in the Dominican Republic (n = 8446). The outcome of interest was a suicide attempt during the past year. The US cultural involvement indicators included time spent living in the United States, number of friends who had lived in the United States, English proficiency, and use of US electronic media and language.

Results. Time lived in the United States, US electronic media and language, and number of friends who had lived in the United States had robust positive relationships with suicide attempts among youths residing in the Dominican Republic.

Conclusions. Our results are consistent with previous research that found increased risk for suicide or suicide attempts among Latino youths with greater US cultural involvement. Our study adds to this research by finding similar results in a nonimmigrant Latin American sample. Our results also indicate that suicide attempts are a major public health problem among youths in the Dominican Republic.

There is growing evidence that US nativity increases risk for suicide ideation, suicide attempts, and death by suicide for Latino youths and adults. Foreign-born Latinos have lower rates of completed suicide compared with US-born Latinos across several national and regional cohorts.1–3 Moreover, rates for suicide ideation or attempts among foreign-born or less acculturated Latinos have been lower than those of their US-born counterparts.4–7

The phenomenon of immigrant Latinos having better health outcomes than US-born Latinos has been referred to by various names, including the healthy immigrant effect, the Latino paradox, and the epidemiological paradox. Moreover, this trend has been found for numerous outcomes.8 A number of models have been proposed to explain this finding including cultural protective factors associated with Latino culture,9,10 discrepancies in intergenerational values between immigrant parents and their US-born children,11 and selection bias related to immigration of healthier or more resilient individuals.12,13 Methodological constraints have unfortunately limited the ability to test determinants that could explain these differences. One constraint that has limited the ability to test the selection bias hypothesis has been the scarcity of comparable data from “feeder” nations that provide US Latino immigrant populations.

In one of the few studies that used cross-national data, Mexican youths in high schools near the US–Mexico border reported lower rates of suicide ideation than Mexican American youths in high schools on the US side of the border.14 In another study using a binational (United States and Mexico) sample of Mexicans, US-born Mexicans and Mexican-born immigrants who arrived in the United States when aged 12 years or younger had higher rates of suicide ideation than Mexicans without a history of migration to the United States or a family member living there. Mexicans with family members living in the United States and US-born Mexicans were also at higher risk for suicide attempts.15 These findings do not support the selection bias explanation for nativity differences in suicide behaviors among adults or youths of Mexican ancestry living in the United States. Although the literature suggests that Latinos share certain core panethnic cultural values such as familism and respect,16–18 the peoples of Latin America have distinct historical, social, immigration, and cultural contexts. It is therefore prudent to test, validate, or disprove explanatory mechanisms such as immigration selection bias across different Hispanic subgroups.

One variation on the approach of using data from feeder countries is to examine how US cultural involvement may relate to risk for suicidal behavior within a non–US setting via mechanisms related to “cultural globalization.” Cultural globalization parallels the process known as economic globalization and refers to the penetration of cultural influences (e.g., US cultural influence) on the lifestyles, values, norms, and retention of cultural heritage in youths around the world.19,20 The strength of this approach is that it examines the relationship between US cultural influence and suicidal behavior in a nonimmigrant Latino population.

The Dominican Republic (DR)—because of its large US-based population,21 relatively close proximity to the United States, and historical connections to the United States22,23—offers an excellent natural experiment to test whether US cultural influence relates to outcomes such as suicide risk behaviors among youths. For example, there are approximately 1.3 million Dominicans living in the United States,21 compared with a relatively modest population of approximately 10 million Dominicans living in the Dominican Republic.24 This ratio of US Dominicans to DR Dominicans makes possible several mechanisms for how cultural globalization in the Dominican Republic may occur, especially as it relates to US cultural influence. The first, circular migration, has been conceptualized and operationalized in multiple ways. We use a literal definition: leaving and then returning to a country of origin, once or repeatedly. Circular migration is often driven by immigrants’ economic circumstances, legal status, and US labor market demands.25 Another mechanism for US cultural influence in the Dominican Republic occurs through ties that Dominicans have with relatives, friends, or acquaintances who live in the United States or who have lived in the United States. The US cultural influence in the Dominican Republic also occurs indirectly via the influences of electronic media such as US-based movies, television, and music.

We examined how US cultural involvement indicators relate to suicide attempts among a nationally representative sample of public high school students in the Dominican Republic. We focused on suicide behavior because it has been identified as a growing worldwide public health concern for youths and young adults.26,27 Moreover, suicide attempts are associated with hospitalization, future attempts,28 and future death by suicide.29,30 Despite prevalent concern about adolescent suicide attempts, little is known about the epidemiology of suicide behaviors in the Dominican Republic.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to publish data on suicide attempts among DR youths that used a nationally representative sample. However, in one unpublished report that used data from a national sample of DR youths attending public school in 1997, as many as 7.9% of the youths reported a suicide attempt during the past year.31 This rate is on par with the 7.7% of youths who reported a suicide attempt during that same year in the United States, but lower than the 10.7% of US Hispanics who reported a suicide attempt in 1997.32 These rates for suicide behavior represent a public health problem among youths in the Dominican Republic. This study will add to the literature by publishing results related to suicide attempts among DR youths in a nationally representative sample and by increasing knowledge regarding the healthy immigrant effect pertaining to suicide attempts. On the basis of the robust associations found between suicide behaviors and US involvement among US Latino and Mexican populations, we hypothesized that greater US cultural involvement would increase risks for suicide attempts among DR youths.

METHODS

We used a stratified cluster sample of public high schools in the Dominican Republic. The strata consisted of 18 national educational regions. The primary sampling units or clusters were DR public high schools. We selected 80 schools for a total of 8446 youths. We randomly selected schools from each educational region in proportion to their numbers nationally; that is, if a region had 10% of the schools in the nation, then approximately 10% of the total schools in the sample came from that region. No region had fewer than 2 schools in the sample. Data were collected by the DR Department of Education via self-administered anonymous surveys in the spring of 2009. In each grade level at each school, an intact classroom of students in a required course was randomly selected to receive the survey. All students present on the day of data collection were eligible. Student participation in the study was voluntary. No school that was selected to participate in the study refused to participate. We created sample weights with population-level data from the DR Department of Education. These data included the total number of current public high school students in the Dominican Republic by grade level, gender, and educational region. The sample weights adjusted results to allow generalization of the results to the population of public high-school students in the Dominican Republic by grade level, gender, and educational region.

Measures

Our outcomes and demographic measures included items from the 2009 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS),33 the Spanish version of the non-Hispanic domain of the Bidimensional Acculturation Scale (BAS),34 and a number of items designed to examine US cultural involvement, family structure, and socioeconomic status. A workgroup of DR- and US-based translators ensured equivalence of meaning between the English and Spanish versions of questions as well as understandability of survey items by DR youths.

US cultural involvement.

We used 4 sets of indicators for US cultural involvement: (1) time lived in the United States, (2) number of friends who have lived in the United States, (3) English proficiency, and (4) use of US electronic media and language.

For time lived in the United States, we created 2 categorical variables: those who had lived in the United States for less than 1 year and those who had lived in the United States for 1 year or longer. The reference group was DR youths who had never lived in or visited the United States.

For number of friends who had ever lived in the United States, we used 1 month as a minimal residence cutoff. The first several response options were actual number of friends from 0 to 4. The last response option was 5 or more.

To measure English proficiency, we used a latent factor with 6 items taken from the BAS that asked about language comprehension. Examples of these items included “How well do you speak English?” and “How well do you read English?” The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) model fit for these 6 items was good (comparative fit index = 0.99; Tucker-Lewis Index = 0.98), with factor loadings ranging from 0.74 to 0.90. Cronbach's α was 0.90. We chose a latent factor strategy rather than creating an index variable to reduce measurement bias and error.35

We used a second latent factor with 6 additional items from the BAS to measure use of US electronic media and language. Examples of these items included “How often do you watch television in English?” and “How often do you speak in English with your friends?” We conceptualized these items as measuring use of US electronic media and language because English-language media in the Dominican Republic comes almost exclusively from US sources (e.g., US cable television). The EFA conducted on these items for our sample supported combining the items into a single factor. The EFA model fit was good (comparative fit index = 0.96; Tucker-Lewis Index = 0.95), with factor loadings ranging from 0.67 to 0.86. Cronbach's α was 0.82.

Control variables.

Control variables were gender, age, urban residence, parental education, dual-parent household, and living in a household with a corrugated zinc roof. Gender was categorized as female or male, and age was coded in years. The DR Department of Education coded schools as urban or not based on local area population density. There were multiple categories for maternal and paternal education, and we recoded these into 2 categorical variables: (1) at least 1 parent who had completed high school, and (2) at least 1 parent who had completed college. Our reference group for parental education was parents who did not complete high school. We defined a dual-parent household as one where there was a mother or mother figure (i.e., grandmother or aunt) and a father or father figure (i.e., grandfather or uncle) residing in the household. Corrugated zinc roofs served as a proxy for poverty. Zinc roofs are seen predominantly on small, inexpensive homes of improvised construction, often located in high-poverty areas in the Dominican Republic.

Outcome variable.

Suicide attempt was measured by the YRBS item “During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” The original response options were 0 (0), 1 (1), 2 (2 or 3), 3 (4 or 5), and 4 (6 or more). We recoded these options to be dichotomous: 0 for no suicide attempt and 1 for any suicide attempt during the past year.

Statistical Analysis

We used Mplus version 5.2 (Muthen and Muthen, Los Angeles, CA) to conduct the analyses. We used the “Type = Complex” command to account for the study's complex survey design. We adjusted all analyses by using sample weights to ensure generalizability to youths in the Dominican Republic attending public high school by gender, grade level, and region of the country.

We conducted our analysis in a stepwise fashion with logistic models. First, we estimated the unadjusted rates for suicide attempt for each of the US cultural involvement indicators by using propensity scores from simple logistic models. We used these same models to estimate unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) for suicide attempt for each indicator of US cultural involvement. Next, we combined all 4 of our US cultural involvement indicators in a single logistic model to estimate the independent relationship of each of our indicators to suicide attempt after adjusting for each other. Our final model took into account the 4 US cultural involvement indicators as well as all of our control variables. To avoid experiment-wise error from multiple group comparisons, we used the Holm–Bonferroni or Holm adjustment.36 We handled missing data with a maximum likelihood approach, thus eliminating or reducing biases associated with missing data.37 There were no violations of the assumptions of logistic regression in any of the models.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows that our sample was predominantly female (57.0%), with a mean age of 16 years. The majority of youths lived in urban areas (67.7%), came from a 2-parent household (56.1%), and never lived in the United States (90.9%). Approximately half lived in an impoverished household as indicated by the presence of a corrugated zinc roof on their homes, about half did not have any friends who have lived in the United States, and 45.8% had parents who had never completed high school. An estimated 8.7% of the population reported having made a suicide attempt during the past year.

TABLE 1—

Sample Characteristics: Public High School Students, Dominican Republic, 2009

| Variable | Weighted % | Unweighted Frequency |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 57.0 | 5205 |

| Male | 43.0 | 3241 |

| Region | ||

| Urban | 67.7 | 5718 |

| Nonurban | 32.3 | 2728 |

| Family structure | ||

| Dual-parent household | 56.1 | 4759 |

| Non–dual-parent household | 43.9 | 3687 |

| Parental education—highest completed | ||

| No parent completed high school | 45.8 | 3834 |

| A parent completed high school | 30.9 | 2601 |

| A parent completed college | 23.3 | 1979 |

| Roof material | ||

| Zinc roof | 49.0 | 3999 |

| Nonzinc roof | 51.0 | 4283 |

| Lived in United States | ||

| Never | 90.9 | 7642 |

| < 1 y | 6.2 | 510 |

| ≥ 1 y | 2.9 | 231 |

| No. of friends lived in United States | ||

| 0 | 49.0 | 4104 |

| 1 | 16.1 | 1337 |

| 2 | 9.4 | 798 |

| 3 | 5.9 | 500 |

| 4 | 2.0 | 175 |

| ≥ 5 | 17.6 | 1457 |

| Suicide attempt during past y | 8.7 | 738 |

Note. The weighted mean age was 16 (SD = 1.5) years. The sample size was n = 8446.

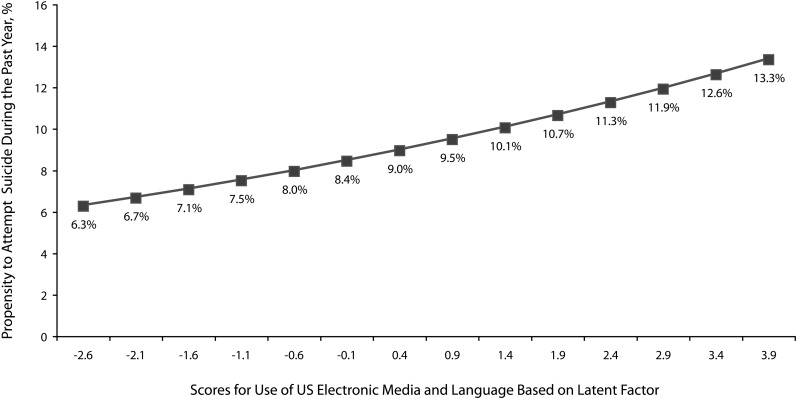

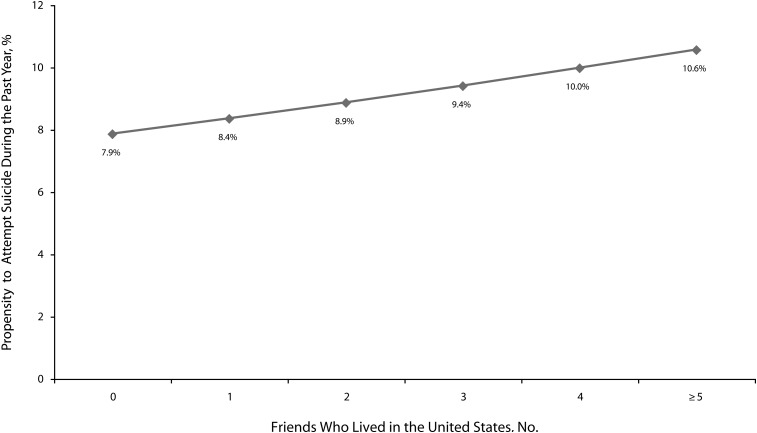

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between use of US electronic media and language and the propensity to attempt suicide. Because we used a latent factor to examine involvement with US electronic media and language, the mean score was 0, with a range of scores between −2.6 and 3.9. There was a significant relationship between use of US electronic media and language and the propensity to attempt suicide, ranging from 6.3% for those at the lowest end of the scale to 13.3% for those at the highest end of the scale. The unadjusted OR from the bivariate logistic regression was 1.14 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.07, 1.21); for every unit increase in the latent factor use of US electronic media and language, the propensity to attempt suicide increased by a factor of 1.14. We found a similar bivariate relationship for the latent factor English proficiency (OR = 1.05; 95% CI = 1.02, 1.09). The bivariate relationship between suicide attempt and number of friends who had lived in the United States was also robust. The propensity to attempt suicide was 7.86% for youths with no friends who had lived in the United States compared with 10.56% for those who had 5 or more friends who had lived in the United States (Figure 2). The unadjusted OR was 1.07 (95% CI = 1.03, 1.11); for every additional friend having lived in the United States, the propensity to attempt suicide increased by a factor of 1.07. The largest differences for the propensity to attempt suicide were found for youths who had never lived in the United States (8.1%) compared with those who had lived in or visited the United States for less than a year (12.6%) and those who had lived in the United States for 1 year or longer (18.2%). The unadjusted ORs comparing youths who had never lived in the United States with those who had lived in the United States for less than a year and those who had lived in the United States for 1 year or longer were 1.65 (95% CI = 1.19, 2.77) and 2.54 (95% CI = 1.67, 3.87), respectively.

FIGURE 1—

Propensity to attempt suicide by use of US electronic media and language: public high school students, Dominican Republic, 2009.

FIGURE 2—

Propensity to attempt suicide by number of friends who have lived in the United States: public high school students, Dominican Republic, 2009.

In the first multivariate model, use of US electronic media and language remained significantly related to suicide behavior after we adjusted for all other US cultural involvement indicators. The same was true for the indicators of time lived in the United States and number of friends who had ever lived in the United States. English proficiency was the only indicator of US cultural involvement that became nonsignificant in this model when adjusted for the other 3 indicators (OR = 0.97; 95% CI = 0.90, 1.04; Table 2).

TABLE 2—

Factors Associated With Suicide Attempt During Past Year: Public High School Students, Dominican Republic, 2009

| Simple Logistic Regression, OR (95% CI) | Multiple Logistic Regression |

||

| Model 1, OR (95% CI) | Model 2, OR (95% CI) | ||

| Lived in United States ≥ 1 ya | 2.54*** (1.67, 3.87) | 2.26*** (1.47, 3.49) | 2.07** (1.32, 3.25) |

| Lived in United States < 1 ya | 1.65*** (1.19, 2.27) | 1.51** (1.09, 2.09) | 1.53** (1.10, 2.11) |

| No. of friends who lived in the United States | 1.07*** (1.03, 1.11) | 1.04* (1.01, 1.08) | 1.05*** (1.01, 1.09) |

| US media and language | 1.14*** (1.07, 1.21) | 1.15* (1.01, 1.33) | 1.17* (1.02, 1.35) |

| English proficiency | 1.05** (1.02, 1.09) | 0.97 (0.90, 1.04) | 0.96 (0.89, 1.03) |

| Age | 0.98 (0.92, 1.05) | ||

| Female | 1.57*** (1.31, 1.88) | ||

| Zinc roof | 0.90 (0.75, 1.09) | ||

| A parent completed high schoolb | 1.00 (0.83, 1.19) | ||

| A parent completed collegeb | 0.89 (0.71, 1.11) | ||

| Dual-parent household | 0.76*** (0.64, 0.91) | ||

| Urban area | 0.79* (0.63, 0.99) | ||

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio. The sample size was n = 8446.

Never lived in the United States is the reference group.

No parent completed high school is the reference group.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

In the final model, we entered the 4 US cultural involvement variables along with the covariates gender, age, parental education, zinc roof, urban residency, and family structure. As with the previous model, all US cultural involvement indicators remained significant except English proficiency. There was also little to modest change in the magnitudes of the ORs across our 3 models, with the exception of English proficiency. Female gender (OR = 1.57; 95% CI = 1.31, 1.88), dual-parent household (OR = 0.76; 95% CI = 0.64, 0.91), and living in an urban area (OR = 0.79; 95% CI = 0.63, 0.99) were also significantly related to suicide attempt in our final model.

DISCUSSION

We found a relation between suicide attempts and US cultural involvement among a national sample of youths attending public high school in the Dominican Republic. Greater number of friends who had lived in the United States, time lived in the United States, and use of US electronic media and language were all independently related to the propensity for a suicide attempt, even when they were all in the same regression model and after we controlled for gender, age, socioeconomic indicators, and family structure. The increases in the propensity to attempt suicide for DR youths across these US cultural involvement indicators were both robust and large. For example, the propensity to attempt suicide ranged from 6.3% for those at the lowest end of the range of use of US electronic media and language to 13.3% for those at the highest end of the range of use of US electronic media and language. This central finding is congruent with the lower suicide or suicide attempt rates found for first-generation or less acculturated Latinos across multiple national and regional cohorts of Latinos.1–7 These findings add to previous research by using a non–US-based sample of youths and examining whether US cultural involvement indicators are associated with suicide attempts.

Our novel methodological framework does not support selection bias related to immigration as the sole explanation for the relationship between US cultural involvement indicators and suicide behavior among Latino youths. However, our findings also do not rule out selection processes related to immigration as a contributing factor for suicide behavior or other outcomes among newly arrived immigrants. Nonetheless, our results are consistent with previously proposed explanatory mechanisms that relate to protective cultural factors in traditional Latino culture or intergenerational discrepancies in cultural values between youths and their parents.

Durkheim wrote more than a century ago about the lower rates of suicide in Catholic versus Protestant countries and how cultural contexts that promote stronger social and familial bonds protect against suicide behavior.38 Values associated with Latino culture such as familism, respect, and affiliative obedience may lead to stronger social and familial bonds between youths and adults.39–41 Moreover, characteristics of traditional Latino culture that promote social control (e.g., parenting behaviors) may help reduce externalizing risk factors associated with suicide attempts, such as substance use, family conflict, and violence. This potential mechanism is consistent with a study that found that the increased risk for suicide attempts among US-born Latino adolescents was mediated by their increased use of illicit substances.7 Another study reported higher levels of risk-taking impulsivity among US-born Latino parents, and this was related to the development of future alcohol dependence in their children.42 Furthermore, Latinos have been found to have greater moral objection to suicide and a greater sense of responsibility to family than non-Latinos, potential mediators that reduce the risk for suicide ideation.43

More research is needed to test how Latino cultural factors relate to suicide behaviors and to known protective and risk factors for suicide behaviors. Studies also are needed to examine whether there are aspects of American culture that give rise to behavioral risk factors associated with suicide behavior. Concepts such as alienation, anomie, or risk-taking impulsivity may be promising risk factors to examine among more Americanized youths.42,44

Intergenerational discrepancies in cultural values and norms may be another mechanism related to increased risk for youths. According to this model, the incongruence in cultural values and norms between Americanized adolescents and their more traditional Latino parents leads to weakening of family bonds, family conflict, role reversal, and adolescent behavior problems and distress. This model has been described by Phinney et al. as intergenerational value discrepancies,11 by Szapocznik and Williams as intercultural/intergenerational conflict,45 and by Portes and Rumbaut as dissonant acculturation.46 There is evidence supporting this model of intergenerational cultural conflict as a factor associated with risk behaviors among Latino youths.47–50 Future research should test the applicability of this model to suicide behavior among Latino youths and identify the role played by shifting cultural values for both parent and child within the family context. For example, parent–child discrepancies in cultural beliefs about family obligations, proper conduct, gender norms, and social role expectations may create conflict within the family environment, but so may greater US cultural involvement among Latino parents.47 Methodological approaches that disentangle the relative effects of intergenerational value discrepancies and shifting cultural norms that may promote or inhibit conflict within family settings may be particularly illuminating.

The results of this study also contain noteworthy public health findings for the youths of the Dominican Republic. To our knowledge, this study is the first to document in the scientific literature that suicide attempts among DR youths are a national public health problem, with 8.7% of the public high-school population reporting a suicide attempt during the past year. Within the US context, similar levels of suicide attempts among high-school students (6.3% in 200933) have been identified as a public health priority and have received private and governmental resources for prevention efforts for years.51,52 The lack of attention to or knowledge of this problem in the Dominican Republic is especially troubling because of its status as a developing country with fewer resources than the United States. An important initial step in addressing this issue would be the creation of a national surveillance system similar to the US Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1991 that can be used to draw attention to and monitor this public health problem. The World Health Organization has started promoting school-based surveillance systems in certain developing nations with their Global School Health Initiative. As of this writing, this initiative has yet to be established in the Dominican Republic.53

Besides surveillance, crucial next steps include creating national health objectives and developing prevention strategies using universal, selective, and indicated approaches, such as those discussed in the report “Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative”54 but that also fit within the DR context. These prevention efforts should also take into account populations with higher or lower risk for suicide attempts. Within this study female gender was associated with higher risk for suicide attempt, a finding consistent with previous research in other nations.26,55–57 Living in an urban environment and residing in a 2-parent household were associated with lower risk for suicide attempt. These results suggest that future prevention efforts within the DR context should take into account the elevated risk for suicide attempt among females, youths living in rural environments, and youths living in single-parent households. For example, one strategy may be to create prevention programs that promote protective factors or reduce risk factors associated with suicide attempts, especially among segments of the population with elevated risk for suicide behavior, such as females. Research is needed to identify what these protective or risk factors may be for youths in the DR context.

Last, this study raises important questions with potential global implications for youths in many nations, including the Dominican Republic and the United States. Is a similar phenomenon occurring in other nations that send large numbers of immigrants to the United States? If US cultural involvement increases risk as shown by our study, will suicide behaviors become an ever-increasing public health problem as globalization increases variety and intensity of exposures to US cultural influences in the Dominican Republic and other developing nations? Moreover, what prevention efforts are needed to reduce suicide behavior among youths in non–US settings that are subject to pervasive US cultural influence? In moving forward with these questions, we emphasize the need to understand how US cultural involvement relates to underlying protective and risk mechanisms that create greater risk among Latino youths in US and non–US settings. We think important mechanisms to explore include those related to negative peer influences, attitudes and norms surrounding behaviors such as suicide attempt, differential gender socialization, social bonds, social control, and family environment. We also stress the need to incorporate into and study the use of cultural values in prevention efforts for Latino youths. For example, culturally sensitive family-based approaches have shown promising results for improving bonding, reducing conflict, and preventing risk in Latino families and adolescents.58–60

Limitations

Our study used self-reported measures that may not be accurate despite previous research suggesting that such items have produced valid responses.61,62 Although youths attending public school in the Dominican Republic represent a significant proportion of the overall adolescent population, results from this study may not generalize to youths who do not attend school or who attend private schools. Moreover, because of issues related to the circular migration patterns between the United States and Dominican Republic, a reverse selection process may be an alternative explanation for our findings. However, use of US electronic media and language was related to suicide risk independent of time lived in the United States, number of friends who have lived in the United States, and English proficiency. We would not expect this finding if the results were solely attributable to high-risk youths returning from the United States.

Conclusions

This study was innovative in its use of a national sample of DR youths to test the relationship between suicide attempt and US cultural involvement. Unlike the majority of studies that have examined this relationship with US-based samples that are subject to selection processes related to migration, this study found a robust relationship between US cultural involvement and suicide attempt in a national sample of youths living in a Latin American country. Future research is needed to replicate findings in the Dominican Republic and other nations and to test potential mechanisms that lead to increased risk for suicide behavior, such as those that suggest that US cultural involvement may erode protective factors in Latino culture or increase intergenerational conflict because of cultural value discrepancies between youths and their parents. To our knowledge, our study is also the first to use a nationally representative sample of students to document that suicide attempt is a public health problem in the Dominican Republic.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant 1R03MH085203-01A1), with additional support from the Center for Latino Family Research at Washington University's Brown School.

Human Participant Protection

Informed consent was obtained from the participants before data collection. All study procedures received institutional review board approval from Washington University's Human Research Protection Office.

References

- 1.Sorenson SB, Shen H. Mortality among young immigrants to California: injury compared to disease deaths. J Immigr Health. 1999;1(1):41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sorenson SB, Shen H. Youth suicide trends in California: an examination of immigrant and ethnic group risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1996;26(2):143–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh GK, Hiatt RA. Trends and disparities in socioeconomic and behavioural characteristics, life expectancy, and cause-specific mortality of native-born and foreign-born populations in the United States, 1979–2003. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):903–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fortuna LR, Perez DJ, Canino G, Sribney W, Alegria M. Prevalence and correlates of lifetime suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Latino subgroups in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(4):572–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vega WA, Gil A, Warheit G, Apospori E, Zimmerman R. The relationship of drug use to suicide ideation and attempts among African American, Hispanic, and White non-Hispanic male adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1993;23(2):110–119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorenson SB, Golding JM. Prevalence of suicide attempts in a Mexican-American population: prevention implications of immigration and cultural issues. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1988;18(4):322–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peña JB, Wyman PA, Brown CHet al. Immigration generation status and its association with suicide attempts, substance use, and depressive symptoms among Latino adolescents in the USA. Prev Sci. 2008;9(4):299–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flores G, Brotanek J. The healthy immigrant effect: a greater understanding might help us improve the health of all children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(3):295–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canino G, Roberts RE. Suicidal behavior among Latino youth. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31(suppl):122–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Range LM, Leach MM, McIntyre Det al. Multicultural perspectives on suicide. Aggression Violent Behav. 1999;4(4):413–430 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phinney JS, Ong A, Madden T. Cultural values and intergenerational value discrepancies in immigrant and non-immigrant families. Child Dev. 2000;71(2):528–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraído-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(10):1543–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pablos-Méndez A. Mortality among Hispanics. JAMA. 1994;271(16):1237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swanson JW, Linskey AO, Quintero-Salinas R, Pumariega AJ, Holzer CE., III A binational school survey of depressive symptoms, drug use, and suicidal ideation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31(4):669–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borges G, Breslau J, Su M, Miller M, Medina-Mora ME, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Immigration and suicidal behavior among Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):728–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villarreal R, Blozis SA, Widaman KF. Factorial invariance of a pan-Hispanic familism scale. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2005;27(4):409–425 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guarnaccia PJ, Martinez I, Acosta H. Mental health in the Hispanic immigrant community: an overview. J Immigr Refug Stud. 2005;3(1/2):21–26 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leidy MS, Guerra NG, Toro RI. A review of family-based programs to prevent youth violence among Latinos. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2010;32(1):5–36 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blum RW, Nelson-Mmari K. The health of young people in a global context. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(5):402–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larson RW. Globalization, societal change, and new technologies: what they mean for the future of adolescence. : Larson R, Brown B, Mortimor J, Adolescents’ Preparation for the Future: Perils and Promise. Ann Arbor, MI: Society for Research on Adolescence; 2002:1–30 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pew Hispanic Center Statistical Portrait of Hispanics in the United States, 2008. Available at: http://pewhispanic.org/files/factsheets/hispanics2008/Table%206.pdf. Accessed January 3, 2011

- 22.Aponte S, CUNY Dominican Studies Institute Dominican Migration to the United States, 1970–1997: An Annotated Bibliography. New York, NY: CUNY Dominican Studies Institute; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pons FM. The Dominican Republic: A National History. 3rd ed Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishing Inc; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Bank, World Development Indicators Dominican Republic Data, 2010. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/country/dominican-republic. Accessed January 31, 2011

- 25.Newland K. United Nations Development Program Human Development Reports: Circular Migration and Human Development, 2009. Available at: http://www.migrationpolicy.org/pubs/newland_HDRP_2009.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2011

- 26.World Health Organization Suicide huge but preventable public health problem, says WHO. 2004. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2004/pr61/en/index.html. Accessed December 19, 2010

- 27.World Health Organization World Health Report 2001-Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfeffer CR, Klerman GL, Hurt SW, Kakuma T, Peskin JR, Siefker CA. Suicidal children grow up: rates and psychosocial risk factors for suicide attempts during follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(1):106–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostamo A, Lönnqvist J. Excess mortality of suicide attempters. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36(1):29–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suokas J, Suominen K, Isometsa E, Ostamo A, Lonnqvist J. Long-term risk factors for suicide mortality after attempted suicide—findings of a 14-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104(2):117–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Westhoff WW. Youth Risk Behaviors. Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: Ministry of Education; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kann L, Kinchen SA, Williams BIet al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 1997. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1998;47(3):1–89 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen Set al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2010;59(5):1–142 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marin G, Gamba RJ. A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: the Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (BAS). Hisp J Behav Sci. 1996;18(3):297–316 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muthen BO. Latent variable modeling in epidemiology. Alcohol Health Res World. 1992;16(4):286 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aickin M, Gensler H. Adjusting for multiple testing when reporting research results: the Bonferroni vs Holm methods. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(5):726–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collins LM, Schafer JL, Kam CM. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychol Methods. 2001;6(4):330–351 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Durkheim E. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. London, UK: Routledge; 1952 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zinn MB. Familism among Chicanos: a theoretical review. Humboldt J Soc Relat. 1982;10(1):224–238 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alegria M, Sribney W, Woo M, Torres M, Guarnaccia P. Looking beyond nativity: the relation of age of immigration, length of residence, and birth cohorts to the risk of onset of psychiatric disorders for Latinos. Res Hum Dev. 2007;4(1):19–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Díaz-Guerrero R. A. Mexican psychology. Am Psychol. 1977;32(11):934–944 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vega WA, Sribney W. Parental risk factors and social assimilation in alcohol dependence of Mexican Americans. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(2):167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oquendo MA, Dragatsi D, Harkavy-Friedman Jet al. Protective factors against suicidal behavior in Latinos. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193(7):438–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Messner SF, Rosenfeld R. The present and future of institutional-anomie theory. : Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevins KR, Taking Stock: The Status of Criminological Theory. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 2006:127–148 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szapocznik J, Williams RA. Brief Strategic Family Therapy: twenty-five years of interplay among theory, research and practice in adolescent behavior problems and drug abuse. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2000;3(2):117–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2001: 44–69 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smokowski PR, Bacallao ML. Acculturation and aggression in Latino adolescents: a structural model focusing on cultural risk factors and assets. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2006;34(5):659–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Parent–child acculturation discrepancies as a risk factor for substance use among Hispanic adolescents in Southern California. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(3):149–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martinez CR., Jr Effects of differential family acculturation on Latino adolescent substance use. Fam Relations. 2006;55(3):306–317 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Félix-Ortiz M, Fernandez A, Newcomb MD. The role of intergenerational discrepancy of cultural orientation in drug use among Latina adolescents. Subst Use Misuse. 1998;33(4):967–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Act of 2004, Pub L No. 108-355, 118 Stat 404.

- 52.US Public Health Service National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.World Health Organization Global School Health Initiative. Available at: http://www.who.int/school_youth_health/gshi/en. Accessed February 2, 2011

- 54.Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE. Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJet al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):98–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cash SJ, Bridge JA. Epidemiology of youth suicide and suicidal behavior. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(5):613–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(3–4):372–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smokowski PR, Bacallao M. Entre dos mundos/between two worlds: youth violence prevention for acculturating Latino families. Res Soc Work Pract. 2009;19(2):165 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gonzales NA, Dumka LE, Mauricio AM, Germán M. Building bridges: strategies to promote academic and psychological resilience for adolescents of Mexican origin. : Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K, Bornstein M, Immigrant Families in Contemporary Society. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007:268–286 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pantin H, Coatsworth JD, Feaster DJet al. Familias Unidas: the efficacy of an intervention to promote parental investment in Hispanic immigrant families. Prev Sci. 2003;4(3):189–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brener ND, Billy JO, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: evidence from the scientific literature. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(6):436–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flisher AJ, Evans J, Muller M, Lombard C. Brief report: test–retest reliability of self-reported adolescent risk behaviour. J Adolesc. 2004;27(2):207–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]