Abstract

Currently, public health emergency preparedness (PHEP) is not well defined. Discussions about public health preparedness often make little progress, for lack of a shared understanding of the topic. We present a concise yet comprehensive framework describing PHEP activities. The framework, which was refined for 3 years by state and local health departments, uses terms easily recognized by the public health workforce within an information flow consistent with the National Incident Management System. To assess the framework's completeness, strengths, and weaknesses, we compare it to 4 other frameworks: the RAND Corporation's PREPARE Pandemic Influenza Quality Improvement Toolkit, the National Response Framework's Public Health and Medical Services Functional Areas, the National Health Security Strategy Capabilities List, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's PHEP Capabilities.

“All models are wrong, some models are useful.”

—George Box1

Public health emergency preparedness (PHEP) has been defined as “the capability of the public health and health care systems, communities, and individuals, to prevent, protect against, quickly respond to, and recover from health emergencies, particularly those whose scale, timing, or unpredictability threatens to overwhelm routine capabilities.”2(p24) However, compared with more traditional public health activities such as food safety inspections, outbreak investigations, community health assessments, immunization clinics, and environmental monitoring, PHEP activities are not clearly defined.2–4

We present a framework describing what public health agencies do to prepare for, respond to, and recover from public health emergencies. The framework was developed through a collaboration of state and local health departments, brought together by the Public Health Informatics Institute with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to define business processes related to PHEP.

The Common Ground Preparedness Framework (CGPF) adds to other PHEP frameworks by more explicitly capturing how public health agencies prepare for and respond to public health emergencies. Combining comprehensiveness with specificity, it is especially useful in describing PHEP to both public health agencies and their partners in emergency response. It also provides a framework for incident action plans and after-action assessments, resource distribution, information systems, and training.

COMMON GROUND PREPAREDNESS FRAMEWORK

In 2006, 6 sites representing state or local public health agencies began a collaboration. “Common Ground: Transforming Public Health Information Systems,” funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and managed by the Public Health Informatics Institute, was a 3-year initiative to help state and local public health agencies better respond to health threats by improving their use of information systems.5 The 6 grantees each provided 2 or 3 core participants, drawing from 4 state and 4 local health agencies, and occasionally brought in additional experts on subject matter. Most sites had at least 1 participant who was consistently involved throughout the project. Advisors from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO), and the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) also participated.

The participants used the Public Health Informatics Institute's Collaborative Requirements Development Process to jointly define shared PHEP business processes.6–8 Initial meetings revealed many potential business processes of varying scope and overlapping boundaries. It became apparent that some common framework was needed for organizing the processes. Participants considered their public health experience along with several frameworks, including the disaster management cycle,9 a preparedness framework from the CDC (prevent, detect and report, investigate, control, recover, and improve),10 the National Response Plan,11 and the Incident Command System (ICS).12 The participants drafted, circulated, and refined a progression of at least 8 frameworks, ultimately agreeing on 3 phases of emergency response and several business process groups, each containing specific processes. Advisors from the CDC, ASTHO, NACCHO, and a peer review group from the leadership of 10 state and local public health departments recognized the framework's potential. At their prompting, the Common Ground collaborators developed the comprehensive framework, and at their final meeting, they achieved consensus on the version, described in the next section.

General Description

The CGPF identifies the business processes required to address an incident that threatens to overwhelm the routine capabilities of a public health system. The processes are grouped into 6 categories: prepare, monitor, investigate, intervene, manage, and recover. Each of these 6 process groups falls within 1 of 3 time periods: preincident, incident, and postincident.

Before an incident, public health organizations prepare by developing capacity for incident response. They also monitor, conducting surveillance to identify new incidents as early as possible. When an incident occurs, they investigate to identify the problem and then intervene to control the problem or its effects. Throughout the incident, public health organizations manage their activities, synthesizing current information to help direct further activities. Finally, recover processes deal with long-term effects of the incident and return operations to normal.

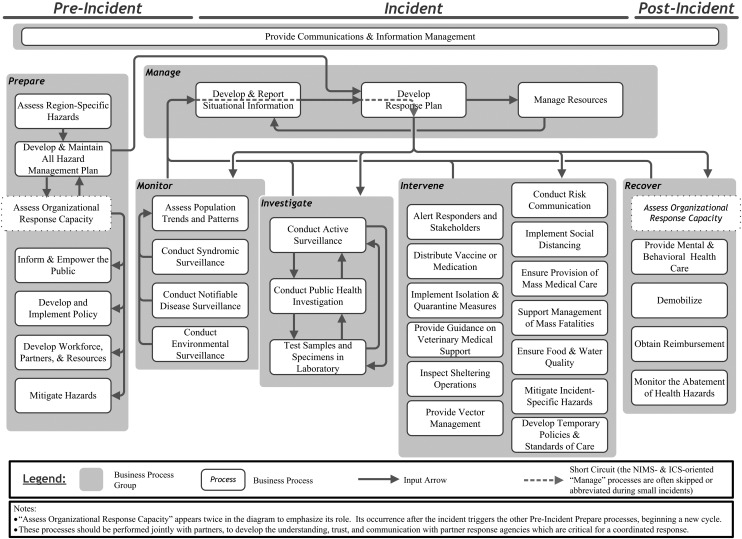

CGPF business processes are interdependent, with output from one process serving as input to another. Figure 1 depicts the framework, with arrows indicating generalized process outputs and inputs.

FIGURE 1—

The Common Ground Preparedness Framework.

Most ordinary activities of public health organizations, including prevention activities, are part of the prepare process group. The monitor and investigate groups overlap because their processes interact closely. However, the monitor processes are ongoing, whereas the investigate processes are activated only when needed. Laboratory testing supports processes from both groups, but it is in the investigate group because of the central role of laboratory testing in public health investigation. The intervene group contains a wide range of processes, including communicating with response partners and the public, isolating the source of the problem, addressing the effects, and supporting those affected. Recover group processes return public health operations to a normal state and address an incident's long-term effects. One process, “assess organizational response capacity,” is shown in both the recover and prepare process groups because it ties postincident evaluations to planning for the next incident.

Consistent with the ICS,12 the manage processes can direct and coordinate other processes by setting objectives, distributing information, and allocating resources. In the absence of ICS, management activities are often informal, occurring within the brain of the person who directs the effort. As incidents escalate, more formal, ICS-based manage processes may be invoked.

An important challenge in emergency preparedness is communication and information flow among processes. CGPF includes a “provide communications and information management” process that spans process groups and incident time periods, indicating its pervasive role.

Syphilis and H1N1 Outbreaks as Framework Examples

Responses to a syphilis outbreak and the H1N1 pandemic demonstrate how the framework can be used. In these descriptions, processes from the CGPF are indicated with quotation marks.

In early 2008, the Marion County Public Health Department (MCPHD) of Indianapolis, IN, saw an increase in syphilis cases. Specifically, MCPHD's “conduct notifiable disease surveillance” and “test samples and specimens in laboratory” processes gathered information that was passed to the “assess population trends and patterns” process, where the increase was detected. The director of the sexually transmitted illness program assessed that information and then stepped up surveillance. In other words, she “developed and reported situational information” and “developed a response plan,” which was to “conduct active surveillance.” She also reviewed the response protocol developed after an earlier syphilis outbreak; an output from the “develop and maintain an all-hazard management plan” process informed the incident's “develop a response plan” process. Information from the ongoing monitor processes indicated a continued increase in cases. This led to another cycle of the “develop and report situational information” and “develop a response plan” processes. The resulting response plan initiated the “conduct public health investigation” process and the “alert responders and stakeholders” process. As the incident expanded, the agency implemented the ICS. With that, the manage processes became more formal, with periodic situation reports and planning meetings. Incident action plans were created by the “develop and report situational information,” “develop a response plan,” and “manage resources” processes. Over time, more interventions were added. The health department “conducted risk communication” to inform the affected community through outreach workers and the media. Patrons of bars and bathhouses received syphilis education and testing, increasing both the “active surveillance” and “risk communication” processes. After a few months, resources were reduced and structured for a long-term effort, through use of the “demobilize” process. Meetings held to evaluate and improve the effort exemplified the “assess organizational response capacity” process.

In its H1N1 pandemic response, the MCPHD had used many of the prepare processes long before the outbreak began. It had “developed and maintained an all-hazard-management plan” that included pandemic influenza, “assessed its organizational response capacity” through various exercises, and “developed workforce, partners, and resources” through staff training, joint planning, and memoranda of understanding with partner agencies. The MCPHD also had “developed and implemented policy” that revised isolation and quarantine ordinances as appropriate for an influenza pandemic, and “informed and empowered the public” through such means as a campaign encouraging families to store emergency supplies and develop an emergency plan. When the H1N1 outbreak began, the MCPHD held daily meetings to “develop and report situational information,” “develop a response plan,” and “manage resources” to fulfill that plan. The situation report was informed by many monitor, investigate, and intervene processes. Within the monitor process group, “conduct syndromic surveillance” produced critical information about emergency department use and laboratory results. The “assess population trends and patterns” process provided timely information about the local spread and impact of H1N1. Through case investigations, the “conduct active surveillance” and “test samples and specimens in laboratory” processes produced information for national trend analyses.

Many intervene processes were also employed. Early in the outbreak, school closings were used to “implement social distancing.” The MCPHD public relations department “conducted risk communication,” encouraging the public to take appropriate precautions, including the “implementation of isolation and quarantine measures.” Several communication systems were used to “alert responders and stakeholders” about evolving treatment recommendations. The MCPHD led local hospitals to “develop temporary policies and standards of care,” including hospital visitor policies and the use of air filtration masks, and to create plans to “ensure the provision of mass medical care” in case the pandemic began to overwhelm local health care resources. As vaccine became available, a huge effort to “distribute vaccine or medication” began, employing many other CGPF processes, such as using the “provide communications and information management” process to manage vaccination records.

When the local epidemic faded, H1N1 workers were “demobilized” and reassigned to their routine work. Surveys were conducted and key participants were interviewed to “assess organizational response capacity,” thereby improving the MCPHD's response to future epidemics. Finally, the MCPHD's administration and finance department used information gathered in the “manage resources” process to “obtain reimbursement.”

COMPARISON OF FRAMEWORKS

Besides the CGPF, there are 4 major PHEP frameworks (Table 1): the National Health Security Strategy (NHSS),13 Emergency Support Function 8 (ESF#8)14 of the National Response Framework (NRF),11 the CDC's Preparedness and Emergency Response Capabilities (PHEP-C),15 and the RAND Corporation's PREPARE for Pandemic Influenza Quality Improvement Toolkit (PPI).16 We compare these with the CGPF to assess its completeness.

TABLE 1—

Preparedness and Emergency Response Frameworks

| Framework (Year Released) | Background | Relevant Content | Strengths |

| NRF (2008) | Replaced the National Response Plan. Presents an overarching framework for all-hazards response in the United States, across all disciplines.11 | Emergency Support Function 8 (ESF#8), “Public Health and Medical Services,” describes 17 core functional areas for public health agencies and health care providers, such as health surveillance, vector control, and patient care.14 | Clarifies which agency or other entity is responsible for what response activities. Provides a common management framework, including the ICS, to improve integration of response operations across different entities. |

| NHSS (2009) | Presents a comprehensive strategy focusing on protecting people's health in an emergency. Public health agencies need proficiency in most of the 50 capabilities defined in the strategy. | Eight capability categories: incident management, community resilience and recovery, infrastructure, health care services, population safety and health, disease containment and mitigation, situational awareness, and quality improvement and accountability.13 | Provides strategic objectives and related capabilities needed by private, community, and government organizations involved in health-related incident response. |

| CDC's PHEP Capabilities (PHEP-C) (2011) | Defined PHEP capabilities for public health departments’ PHEP cooperative agreement proposals and strategic planning. | Lists 15 capabilities in 6 categories: biosurveillance, community resilience, countermeasures and mitigation, incident management, information management, and surge management.15 | Translates relevant NHSS capabilities into public health terms, and identifies tools, skills, and response plan elements needed by health departments for those capabilities. |

| PPI (2008) | The PPI evolved from several RAND Corporation projects that described public health preparedness activities.2,17 The PPI refines this work. | Includes a framework with 6 PHEP process domains (surveillance, command and control, case reporting and investigation, risk communication, disease control, and disease treatment) and supporting factors such as “strong leadership.”16 | Provides a clear methodology for evaluating and improving PHEP. Provides specifics about some public health response processes. |

| CGPF (2011) | Enumerates public health agency PHEP business processes and the information flow between processes. | Contains 6 process groups (prepare, monitor, investigate, intervene, manage, and recover) and 35 PHEP business processes. | For public health agency PHEP, the comprehensiveness and specificity is useful for planning, after-action evaluation, and describing the agency's role in incident response. |

Note. CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CGPF = Common Ground Preparedness Framework; ICS = Incident Command System; NHSS = National Health Security Strategy; NRF = National Response Framework; PHEP = public health emergency preparedness; PPI = PREPARE for Pandemic Influenza Quality Improvement Toolkit.

Scope Comparisons

There are significant differences in scope between these frameworks. The NHSS and the NRF's ESF#8 encompass a broad view of health-related emergency management that includes public health as one of many entities. The PHEP-C synthesizes 21 NHSS capabilities into 15 capabilities, each containing several functions and many tasks specific to public health. Rather than focusing on capabilities, the CGPF and PPI focus on processes and activities. The CGPF is more comprehensive than the PPI with regard to PHEP activities, whereas the PPI has more focus on evaluation and includes contextual factors that influence emergency response outcomes.

Completeness Comparisons

To assess the completeness of the CGPF, Table 2 lists the public health–related functional areas or capabilities of the 4 comparison frameworks, and indicates whether the CGPF business processes address each functional area or capability. The following differences were found.

TABLE 2—

Comparison of the Common Ground Preparedness Framework With Other Selected Frameworks

| CGPF Group | CGPF Business Process | Other Framework | Item From Other Framework |

| Prepare | All “prepare” processes | CDC | Community preparedness |

| Assess region-specific hazards | NHSS | Risk assessment and risk management | |

| Develop and maintain all hazard management plan | NHSS NHSS | Integrated support from nongovernmental organizations Risk assessment and risk management | |

| NHSS | Risk assessment and risk management | ||

| NHSS | Access to health care and social services | ||

| NHSS | Use of capability-based performance measures | ||

| NHSS | Use of quality improvement methods | ||

| Assess organizational response capacity | NHSS | Reconstitution of the public health, medical, and behavioral health infrastructure | |

| NHSS | Sufficient, culturally competent, and proficient public health, health care, and emergency management workforce | ||

| NHSS | Interoperable and resilient communications systems | ||

| NHSS | Use of capability-based performance measures | ||

| NHSS | Use of quality improvement methods | ||

| Inform and empower the public | NHSS | Public education to inform and prepare individuals and communities | |

| NHSS | Public engagement in local decision-making | ||

| NHSS | Local social networks for preparedness and resiliencea | ||

| NHSS | Use of quality improvement methods | ||

| Develop and implement policy | NHSS | Sufficient, culturally competent, and proficient public health, health care, and emergency management workforce | |

| NHSS | Legal protections and authorities | ||

| NHSS | Access to health care and social services | ||

| NHSS | Use of quality improvement methods | ||

| Develop workforce, partners, and resources | NHSS | Local social networks for preparedness and resiliencea | |

| NHSS | Integrated support from nongovernmental organizations | ||

| NHSS | Sufficient, culturally competent, and proficient public health, health care, and emergency management workforce | ||

| NHSS | Volunteer recruitment and management | ||

| NHSS | Use of quality improvement methods | ||

| Mitigate hazards | NHSS | Mitigated hazards to health and public health facilities and systems | |

| NHSS | Risk assessment and risk management | ||

| NHSS | Environmental health | ||

| NHSS | Use of quality improvement methods | ||

| Monitor | All “monitor” processes | CDC | Public health surveillance and epidemiological investigation |

| PPI | Surveillance | ||

| ESF | Health surveillance | ||

| NHSS | Risk assessment and risk management | ||

| ESF | All-hazard public health and medical consultation, technical assistance, and support | ||

| NHSS | Epidemiological surveillance and investigation | ||

| NHSS | Near-real-time systems for capture and analysis of health security-related data | ||

| Conduct environmental surveillance | ESF | Food safety and security | |

| ESF | Public health aspects of potable water, wastewater, and solid waste disposalb | ||

| NHSS | Agriculture surveillance and food safety | ||

| NHSS | Chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosives (CBRNE) detection and mitigation | ||

| NHSS | Environmental health | ||

| NHSS | Potable water, wastewater, and solid waste disposal | ||

| Assess population trends and patterns | NHSS | Case management support or individual assistancec | |

| NHSS | Information gathering and recognition of indicators and warning | ||

| Investigate | All “investigate” processes | CDC | Public health surveillance and epidemiological investigation |

| PPI | Case reporting and investigation | ||

| ESF | Health surveillance | ||

| ESF | All-hazard public health and medical consultation, technical assistance, and support | ||

| ESF | Vector control | ||

| NHSS | Epidemiological surveillance and investigation | ||

| NHSS | Agriculture surveillance and food safety | ||

| Conduct public health investigation | ESF | Public health aspects of potable water, wastewater, and solid waste disposalb | |

| NHSS | Animal disease surveillance and investigationa | ||

| NHSS | Potable water, wastewater, and solid waste disposal | ||

| Test samples and specimens in laboratory | CDC | Public health laboratory testing | |

| ESF | Public health aspects of potable water, wastewater, and solid waste disposalb | ||

| NHSS | Animal disease surveillance and investigationa | ||

| NHSS | Laboratory testing | ||

| NHSS | Potable water, wastewater, and solid waste disposal | ||

| Intervene | Several “intervene” processes | CDC | Nonpharmaceutical interventions |

| Alert responders and stakeholders | NHSS | Emergency public information and warning | |

| NHSS | Epidemiological surveillance and investigation | ||

| NHSS | Chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosives (CBRNE) detection and mitigation | ||

| NHSS | Communications among responders | ||

| Conduct risk communication | CDC, NHSS | Emergency public information and warning | |

| PPI | Risk communication | ||

| ESF | Public health and medical information | ||

| NHSS | Epidemiological surveillance and investigation | ||

| NHSS | Community interventions for disease control | ||

| NHSS | Individual evacuation and shelter in place | ||

| Distribute vaccine or medication | CDC | Medical countermeasure dispensing | |

| PPI | Disease control | ||

| PPI | Disease treatment | ||

| ESF | Patient carea,c | ||

| NHSS | Epidemiological surveillance and investigation | ||

| NHSS | Chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosives (CBRNE) detection and mitigation | ||

| NHSS | Administration of medical countermeasures | ||

| Implement social distancing | PPI | Disease control | |

| NHSS | Community interventions for disease control | ||

| Implement isolation and quarantine measures | PPI | Disease control | |

| ESF | Patient carea,c | ||

| NHSS | Community interventions for disease control | ||

| Ensure provision of mass patient care | CDC, NHSS | Medical surge | |

| PPI | Disease treatment | ||

| NHSS | Access to health care and social services | ||

| NHSS | Use of remote medical care technology | ||

| NHSS | Emergency triage and prehospital treatmentc | ||

| NHSS | Patient transportc | ||

| NHSS | Palliative care education for stakeholdersa,c | ||

| Provide guidance on veterinary support | ESF | All-hazard public health and medical consultation, technical assistance, and support | |

| ESF | Veterinary medical supporta,b | ||

| NHSS | Animal disease surveillance and investigationa | ||

| Support management of mass fatalities | CDC, NHSS | Fatality management | |

| ESF | Mass fatality management, victim identification, and decontaminating remains | ||

| Inspect sheltering operations | CDC, NHSS | Mass care (sheltering, feeding, and related services)a,c | |

| Ensure food and water quality | ESF | Food safety and security | |

| ESF | Public health aspects of potable water, wastewater, and solid waste disposalb | ||

| NHSS | Reconstitution of the public health, medical, and behavioral health infrastructure | ||

| NHSS | Agriculture surveillance and food safety | ||

| NHSS | Potable water, wastewater, and solid waste disposal | ||

| Provide vector management | ESF | Vector control | |

| NHSS | Reconstitution of the public health, medical, and behavioral health infrastructure | ||

| NHSS | Animal disease surveillance and investigationa | ||

| NHSS | Environmental health | ||

| Mitigate incident-specific hazards | NHSS | Reconstitution of the public health, medical, and behavioral health infrastructure | |

| NHSS | Chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosives (CBRNE) detection and mitigation | ||

| NHSS | Environmental health | ||

| Recover | All “recover” processes | CDC | Community recovery |

| NHSS | Reconstitution of the public health, medical, and behavioral health infrastructure | ||

| Provide mental and behavioral health care | ESF | Behavioral health carea,c | |

| NHSS | Case management support or individual assistancec | ||

| NHSS | Access to health care and social services | ||

| NHSS | Evidence-based behavioral health prevention and treatment services | ||

| NHSS | Monitoring of physical and behavioral health outcomes | ||

| Demobilize | NHSS | Critical resource monitoring, logistics and distribution | |

| Obtain reimbursement | NHSS | Critical resource monitoring, logistics and distribution | |

| Monitor the abatement of health hazards | NHSS | Chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosives (CBRNE) detection and mitigation | |

| NHSS | Monitoring of physical and behavioral health outcomes | ||

| NHSS | Environmental health | ||

| Manage | All “manage” processes | CDC | Emergency operations coordination |

| PPI | Command and control | ||

| ESF | Assessment of public health and medical needs | ||

| ESF | Health, medical, and veterinary equipment and supplies | ||

| ESF | Medical care personnel | ||

| ESF | Patient carea,c | ||

| ESF | All-hazard public health and medical consultation, technical assistance, and support | ||

| NHSS | Monitoring of available health care resources | ||

| NHSS | On-site incident management and multiagency coordination | ||

| Develop and report situational information | NHSS | Coordination with US and international partnersa | |

| NHSS | Critical resource monitoring, logistics and distribution | ||

| Manage resources | CDC | Medical materiel management and distribution | |

| CDC | Volunteer management | ||

| CDC, NHSS | Medical surge | ||

| CDC, NHSS | Responder safety and health | ||

| PPI | Disease treatment | ||

| NHSS | Reconstitution of the public health, medical, and behavioral health infrastructure | ||

| NHSS | Volunteer recruitment and management | ||

| NHSS | Critical resource monitoring, logistics and distribution | ||

| NHSS | Research, development, and procurement of medical countermeasuresa | ||

| NHSS | Management and distribution of medical countermeasures | ||

| NHSS | Medical equipment and supplies monitoring, management, and distribution | ||

| NHSS | Monitoring of physical and behavioral health outcomes | ||

| Provide communications and information | CDC | Information sharing | |

| management | NHSS | Interoperable and resilient communications systems | |

| NHSS | Near-real-time systems for capture and analysis of health security-related data | ||

| NHSS | Information gathering and recognition of indicators and warning | ||

| NHSS | Communications among responders | ||

| NHSS | Medical equipment and supplies monitoring, management, and distribution | ||

| NHSS | Use of remote medical care technology | ||

| Not in CGPF | Not in CGPF | ESF | Patient evacuationc |

| ESF | Safety and security of drugs, biologics, and medical devicesc | ||

| ESF | Blood and blood productsc | ||

| ESF | Agriculture safety and securityb | ||

| ESF | Worker safety and healthb | ||

| NHSS | Postincident social network reengagement | ||

| NHSS | Support services network for long-term recovery | ||

| NHSS | Application of clinical practice guidelinesc | ||

| NHSS | Emergency public safety and security |

Note. CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Preparedness and Emergency Response Capabilities; CGPF = Common Ground Preparedness Framework; ESF = Emergency Support Function 8 [ESF#8] Core Functional Area; NHSS = National Health Security Strategy Capability; PPI = RAND Corporation's PREPARE for Pandemic Influenza Quality Improvement Toolkit Activity. Five CGPF processes had no specific matching items from the other frameworks: “conduct syndromic surveillance,” “conduct notifiable disease surveillance,” “conduct active surveillance,” “develop temporary policies and standards of care,” and “develop response plan.”

CGPF provides only minimal coverage.

Public health agencies usually play a supporting rather than lead role.

Primarily a Clinical Care System responsibility.

National Response Framework and Emergency Support Function 8 core functional areas.

The NRF groups emergency response activities into 15 emergency support functions (ESFs). ESF#8 is triggered “on notification of an actual or potential public health or medical emergency,”14 so the preincident prepare business processes of the CGPF are beyond the scope of ESF#8. As indicated in the last row of Table 2, ESF#8 core functions that are not covered by the CGPF are those that usually fall to other government agencies or to the clinical care system.

National Health Security Strategy capabilities.

The NHSS encompasses many interrelated systems, including public health, that contribute to national health security. The NHSS capabilities are analogous to CGPF business processes.13 Most of the NHSS capabilities are accounted for in the CGPF, and vice versa. However, the NHSS Community Resilience and Recovery area has a broader scope than the CGPF “recover” business processes. Most NHSS capability names are more general than CGPF process names; CGPF processes are more specific to public health agencies. Unlike the CGPF, the NHSS does not show interdependences between its components. In general, the CGPF may be regarded as a more specific, structured depiction of the public health system preparedness work described in the NHSS.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Public Health Emergency Preparedness Capabilities.

The PHEP-C and CGPF present fairly distinct aspects of PHEP. The PHEP-C enumerates 65 distinct functions, more than 200 distinct tasks, and many resources, whereas the CGPF has more emphasis on processes and connections between processes. The PHEP-C is useful as a checklist, whereas the CGPF is more useful as a description of operations. Both cover similar content, although the PHEP-C has relatively greater emphasis on direct clinical care activities and resource management, and less on the other CGPF areas.

RAND Corporation's PREPARE for Pandemic Influenza Quality Improvement Toolkit.

The PPI includes 6 domains, similar to CGPF business process groups, and 6 supporting factors necessary to achieve desired outcomes.16 A notable difference in scope is that the PPI omits processes related to preparing for and recovering from an incident. The PPI includes supporting and contextual factors, such as “robust supply chain” and “strong leadership,” not directly addressed in the CGPF.

REMARKS

The CGPF comprehensively describes PHEP activities. Its organization, information flow, and level of detail are sufficient to provide good descriptions of a health department's response to ordinary and extraordinary public health emergencies.

Compared with the broad preparedness framework of the NRF, the CGPF more precisely defines the work of public health within emergency preparedness and response, and presents it in terms familiar to public health practitioners. The NHSS capabilities list is at a level of detail and comprehensiveness similar to that of the CGPF, but the CGPF uses terms that better describe public health tasks, and shows the roles and relationships of processes as incident response unfolds. However, the CGPF might be improved by expanding its recovery process group with content from the NHSS. The CGPF and PHEP-C are similar in scope, but differ in emphasis and approach. Compared with the PPI, the CGPF provides substantially more detail and includes processes beyond the PPI's scope. However, the CGPF does not address important contextual, supporting capabilities such as leadership and community support.

Uses of the Common Ground Preparedness Framework

Preparedness planning, coordination, and quality improvement.

Because it is comprehensive and process oriented, the CGPF can organize system development, response planning, and evaluation. The CGPF structure supports comprehensive planning and after-action assessments, resource coordination, and development of incident action plans. For instance, Ohio's Department of Health used the framework to help organize their response to the nH1N1 pandemic (R. Campbell, deputy director, Center for Public Health Statistics and Informatics, Ohio Department of Health, written communication, September 7, 2011). During a multiagency incident response, the CGPF may clarify which operations might be best addressed with public health agency resources.

Systems development.

Because the CGPF is understandable to program staff yet uses a format familiar to system developers, it can help bridge the gap in understanding that often exists between program and technical groups. For instance, an earlier draft of the CGPF was included in public health recommendations for syndromic surveillance reporting requirements,18 so that vendors seeking Meaningful Use certification19 for their electronic health record software could understand how syndromic surveillance interacts with other public health processes. It was also used by the Common Ground collaborators to prioritize PHEP processes for detailed analysis and redesign; the results are available on the Public Health Informatics Institute's Web site.20

Training.

The CGPF is also useful for explaining PHEP to new public health staff and to external partners. The prepare, monitor, investigate, intervene, and recover process groups provide a sensible framework for audiences that are not familiar with public health operations. The framework illustrates the breadth of preparedness activities, and supporting materials20 can then provide additional detail for processes of interest.

Resource prioritization.

By providing a systematic view of PHEP, the CGPF may help identify high-consequence failure points or, conversely, opportunities for investments that will support multiple processes. Aligning resource allocations against the CGPF can highlight gaps or imbalances. This is especially useful when explaining how new resources may be optimally applied. For instance, a grant application that explains how enhancements will improve related processes and strengthen the agency's overall preparedness may be more successful than applications lacking a systems-oriented justification.

Incident Command System.

Since 2006, public health agencies receiving federal preparedness funding have been required to adopt ICS for emergency response.21 It has been difficult for many in public health to integrate the formal, compartmentalized ICS management methods into their work.22 The CGPF places familiar public health activities into a flow that includes ICS processes. Public health managers already routinely, though usually informally, assess situations, develop informal action plans, and allocate resources. The CGPF explicitly includes these processes in the manage process group, clarifying how ICS may be integrated with traditional pubic health operations.

Future Work

The CGPF and supporting documents are currently available through the Public Health Informatics Institute.20,23,24 The framework continues to be presented to public health practitioners at meetings and conferences. NACCHO, ASTHO, and the National Association for Chronic Disease Directors have distributed the framework to their members and continue to host links to the Public Health Informatics Institute's Web site. Materials for emergency responders are being prepared to aid their understanding of public health's role in emergency response. However, we expect refinement of the CGPF will continue.

The CGPF might be enhanced by adding information about contextual factors, such as leadership or community support, although that would make the framework more complex. Additions to the recovery process group, modeled on NHSS community resilience and recovery capabilities, might also enhance the CGPF. The processes listed at the end of Table 2 might be included in jurisdictions where public health is responsible for those activities.

Evaluating how specific scenarios flow through the framework may identify gaps and areas for improvement. The framework's robustness might best be tested by using it to describe incidents that vary with respect to threat (biological vs chemical), occurrence (natural vs intentional), and scope (local vs national).

PHEP frameworks such as the CGPF must allow for the evolution of public health threats and interventions. Although specific processes may change over time, however, we believe that the CGPF structure will remain robust.

The CGPF will only be valuable if it is used, and wide adoption of something new depends more on successful use by early adopters and opinion leaders than on publication in a journal.25 Most public health authority in the United States resides in state and local agencies, so a rollout strategy must rely heavily on a partnership with those agencies. Toward that end, the Public Health Informatics Institute continues to work with associations of those agencies, as well as with federal partners, to gain endorsement for the framework and to integrate it into public health training.

CONCLUSIONS

The CGPF concisely yet comprehensively captures the emergency preparedness activities of public health agencies. It uses processes and information flows familiar to public health workers, helping them recognize how their daily work fits within emergency preparedness. The level of specificity is also useful in planning, training, system development, quality improvement, and explaining public health's role to emergency response partners. It reflects the cohesiveness and flexibility of PHEP, with interdependent, linked business processes that can be selectively invoked and scaled in response to the specifics of an incident.

The CGPF is consistent with the frameworks used by other emergency response entities, but it uses terms and concepts familiar to public health workers. Ultimately, adoption of CGPF will reduce confusion over public health's role in emergency response and move us toward a clearer common vision of public health emergency preparedness.

Acknowledgments

The Common Ground Preparedness Framework was created and refined throughout the 3-year Common Ground preparedness collaborative. Although the 3 authors prepared the article, the framework itself is substantially the work of the entire group of Common Ground Preparedness grantees, including representatives of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Cambridge (MA) Department of Public Health, Children's Hospital Boston, the Marion County (IN) Public Health Department, the New York State Department of Health, the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the Metro Public Health Department of Nashville–Davidson County (TN), the Spokane (WA) Regional Health District, and the Washington State Department of Health.

We are grateful to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for funding the collaborative, to the Public Health Informatics Institute for their excellent management of the project, and to our peers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, the National Association of County and City Health Officials, and other health departments whose critiques helped us refine the framework.

We especially recognize our great friend and collaborative member, Don Ward, who passed away shortly before this manuscript was completed. This reflects just a small piece of his life of contributions to public health.

Human Participant Protection

Because this article did not use human participant research, institutional review board approval was not needed.

References

- 1.Box GEP. Robustness in the strategy of scientific model building. : Launer RL, Wilkinson GN, Robustness in Statistics: Proceedings of a Workshop. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1979. Available at: http://stinet.dtic.mil/oai/oai?&verb=getRecord&metadataPrefix=html&identifier=ADA070213. Accessed April 22, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson C, Lurie N, Wasserman J, Zakowski S, Leuschner KJ. Conceptualizing and defining public health emergency preparedness. RAND Health; 2008. Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WR543. Accessed April 16, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asch SM, Stoto M, Mendes Met al. A review of instruments assessing public health preparedness. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(5):532–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson C, Lurie N, Wasserman J. Assessing public health emergency preparedness: concepts, tools, and challenges. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28(1):1–18 Available at: http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144054?select23=Choose&journalCode=publhealth. Accessed April 16, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Public Health Informatics Institute RWJF Common Ground. Available at: http://www.phii.org/programs/CommonGround.asp. Accessed April 13, 2011

- 6.Taking Care of Business: A Collaboration to Define Local Health Department Business Processes. Decatur, GA: Public Health Informatics Institute; 2006:79 Available at: http://www.phii.org/resources/doc/Taking_Care_of_Business.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinman AR, Mann MY, Singh RH. Newborn dried bloodspot screening: mapping the clinical and public health components and activities. Genet Med. 2009;11(6):418–424 Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.proxy.medlib.iupui.edu/pubmed/19369886. Accessed September 13, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams W, Lyalin D, Wingo PA. Systems thinking: what business modeling can do for public health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2005;11(6):550–553 Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.proxy.medlib.iupui.edu/pubmed/16224291. Accessed September 13, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Settle AK. Financing disaster mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. Public Adm Rev. 1985;45:101–106 Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3135004. Accessed August 9, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public health preparedness: mobilizing state by state. CDC public health preparedness report—background. 2007. Available at: http://www.bt.cdc.gov/publications/feb08phprep/background.asp. Accessed April 23, 2010

- 11.US Dept of Homeland Security National response plan. 2004. Available at: http://www.dhs.gov/files/programs/editorial_0566.shtm. Accessed August 9, 2011

- 12.US Dept of Homeland Security NIMS Resource Center—Federal Emergency Management Agency. Available at: http://www.fema.gov/emergency/nims. Accessed May 24, 2010

- 13.US Dept of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response National Health Security Strategy of the United States of America. 2009. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/aspr/opsp/nhss/nhss0912.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2010

- 14.US Dept of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency Emergency support function #8—public health and medical services annex. Available at: http://www.fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nrf/nrf-esf-08.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2010

- 15.Kahn AS, Kosmos C, Singleton C-Met al. Public health preparedness capabilities: national standards for state and local planning. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/capabilities. Accessed August 9, 2011

- 16.Lotstein D, Leuschner KJ, Ricci KA, Ringel JS, Lurie N. PREPARE for Pandemic Influenza: A Quality Improvement Toolkit. RAND Health; 2008:217 Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR598. Accessed April 22, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lotstein D, Ricci KA, Stern Set al. Enhancing public health preparedness: exercises, exemplary practices, and lessons learned, phase III: task B2: final report: promoting emergency preparedness and readiness for pandemic influenza (PREPARE for PI): pilot quality improvement learning collaborative. RAND Health; 2007:57 Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WR491. Accessed April 22, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Society for Disease Surveillance Final recommendation: core processes and EHR requirements for public health syndromic surveillance. 2011:69 Available at: http://www.syndromic.org/projects/meaningful-use. Accessed April 9, 2011

- 19.Dept of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Meaningful use EHR incentive programs. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/EHRIncentivePrograms/30_Meaningful_Use.asp. Accessed April 9, 2011

- 20.Common Ground Preparedness Workgroup Common Ground: Public Health Preparedness Toolkit. Decatur, GA: Public Health Informatics Institute; 2011:77 Available at: http://www.phii.org/resources/doc_details.asp?id=161. Accessed April 8, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Dept of Homeland Security Homeland Security Presidential Directive 5: Management of Domestic Incidents. 2003. Available at: http://www.dhs.gov/xabout/laws/gc_1214592333605.shtm. Accessed April 9, 2011

- 22.Lurie N, Wasserman J, Nelson CD. Public health preparedness: evolution or revolution? Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25(4):935–945 Available at: http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/25/4/935.abstract. Accessed April 13, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Common Ground Preparedness Workgroup Requirements for Public Health Preparedness Information Systems. Decatur, GA: Public Health Informatics Institute; 2010:85 Available at: http://www.phii.org/resources/doc_details.asp?id=158. Accessed August 26, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Public Health Informatics Institute A product of the Common Ground Project supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Common Ground Preparedness Framework animated walk-through. 2011. Available at: http://www.phii.org/resources/doc_details.asp?id=165. Accessed August 26, 2011

- 25.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 4th ed. New York, NY: Free Press; 1995 [Google Scholar]