Abstract

To investigate the short-term effect of elevated temperatures on carbon metabolism in growing potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers, developing tubers were exposed to a range of temperatures between 19°C and 37°C. Incorporation of [14C]glucose (Glc) into starch showed a temperature optimum at 25°C. Increasing the temperature from 23°C or 25°C up to 37°C led to decreased labeling of starch, increased labeling of sucrose (Suc) and intermediates of the respiratory pathway, and increased respiration rates. At elevated temperatures, hexose-phosphate levels were increased, whereas the levels of glycerate-3-phosphate (3PGA) and phosphoenolpyruvate were decreased. There was an increase in pyruvate and malate, and a decrease in isocitrate. The amount of adenine diphosphoglucose (ADPGlc) decreased when tubers were exposed to elevated temperatures. There was a strong correlation between the in vivo levels of 3PGA and ADPGlc in tubers incubated at different temperatures, and the decrease in ADPGlc correlated very well with the decrease in the labeling of starch. In tubers incubated at temperatures above 30°C, the overall activities of Suc synthase and ADPGlc pyrophosphorylase declined slightly, whereas soluble starch synthase and pyruvate kinase remained unchanged. Elevated temperatures led to an activation of Suc phosphate synthase involving a change in its kinetic properties. There was a strong correlation between Suc phosphate synthase activation and the in vivo level of Glc-6-phosphate. It is proposed that elevated temperatures lead to increased rates of respiration, and the resulting decline of 3PGA then inhibits ADPGlc pyrophosphorylase and starch synthesis.

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) yield is limited by high temperatures, which restricts the use of this plant in the tropics (Awan, 1964; Burton, 1986), the optimum temperature for tuber growth being around 22°C (Burton, 1986). Several factors could be responsible for this phenomenon. Elevated temperatures lead to (a) increased photorespiration and inhibition of net photosynthesis in leaves (Berry and Björkman, 1980); (b) increased respiration rates and therefore a considerable loss of photosynthate in growing sinks such as roots (Farrar and Williams, 1991); and (c) a reduction of Suc import into storage sinks such as potato tubers (Wolf et al., 1990).

However, several studies provide evidence that the reduced carbon import into potato tubers at high temperature is attributable to reduced Suc mobilization in the tuber itself, and not just to a shortage of photosynthate supply (Kraus and Marschner, 1984; Mohabir and John, 1988; Wolf et al., 1991). There are two lines of evidence. First, inhibition of potato tuber growth at elevated soil temperatures is accompanied by increased Suc levels in the tubers as well as in the leaves, indicating a block of Suc breakdown and starch synthesis in the tubers (Wolf et al., 1991; Midmore and Prange, 1992). Second, compared with other cellular processes such as respiration, which increase with temperature up to 40°C, the optimum temperature for starch synthesis is relatively low (Mohabir and John, 1988). Short-term experiments with [14C]Suc supplied to discs of growing potato tubers (Mohabir and John, 1988) demonstrated a sharp temperature optimum for starch synthesis at approximately 21.5°C. Increasing the temperature to 30°C led to a 50% reduction of starch synthesis, whereas respiration rates were increased 2-fold. This was also confirmed in long-term experiments (Kraus and Marschner, 1984). When individual tubers of a potato plant were subjected to 30°C for 6 d, incorporation of 14C-labeled assimilates into starch, as well as the starch content and the growth rate of the tubers, were significantly reduced, whereas the incorporation of 14C-labeled assimilates into the sugar fraction was not affected by high tuber temperature.

The reasons for this decrease in starch synthesis at elevated temperatures are not clear. Decreased starch synthesis at elevated temperatures could be caused by (a) a direct inhibition of starch biosynthetic enzymes in the plastid (i.e. increased heat-stress susceptibility or thermolability of enzyme activities) and/or (b) a decrease in the levels of precursors caused by increased respiration or decreased Suc mobilization. Elevated temperatures led to a decrease in AGPase activity when individual tubers of a potato plant were subjected to 30°C for 6 d (Kraus and Marschner, 1984), or to a reduction of AGPase and SuSy activities in the tubers when whole potato plants were transferred from 19/17°C to 29/27°C (day/night) for 14 d (Lafta and Lorenzen, 1995), indicating that the site responsible for this temperature-induced response is associated with AGPase or SuSy. Short-term studies, however, indicate that the temperature sensitivity of starch synthesis is caused by an interaction with processes in the cytosol because a temperature shift from 21 to 31°C perturbed starch synthesis in tissue slices but not in cell-free amyloplasts of potato tubers (Mohabir and John, 1988).

At present, interpretation of changes in respiration, starch, and Suc metabolism at elevated temperature in potato tubers is limited by a lack of detailed information about changes in the levels of metabolites and nucleotides. This information is necessary to decide at which site(s) inhibition of starch synthesis occurs and to elucidate possible regulation mechanisms. In this article, our aim was to identify the enzymatic step(s) at which fluxes are being regulated in response to a short-term increase in temperature. To do this, we incubated growing potato tubers at different temperatures from 19°C to 37°C, measured the flux of [14C]Glc to starch, Suc, or glycolysis, and investigated changes in the levels of metabolites in the pathway from Suc to starch, as well as glycolytic intermediates, organic acids, and nucleotides. To elucidate a possible regulatory mechanism, we also investigated several enzyme activities, including AGPase, soluble starch synthase, SuSy, and SPS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L., cv Desirée) plants (Saatzucht Fritz Lange, Bad Schwartau, Germany) were grown in a growth chamber (350 μmol photons m−2 s−1, 20°C, 50% RH) in 5-L pots in soil supplemented with Hakaphos grün (100 g/230 L soil; BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany) under a 14-h/10-h day/night regime. Growing tubers (about 2–4 g fresh weight) from 6- to 8-week-old daily-watered plants were used for the experiments. The tubers had high activities of SuSy, which is taken as an indicator of rapidly growing tubers (Merlo et al., 1993).

Labeling Experiments and Fractionation of 14C-Labeled Tissue Extract

Labeling experiments were carried out with intact, growing tubers taken from fully photosynthesizing plants. Immediately after harvest, tubers (approximately 2–4 g fresh weight) were incubated in wet sand at temperatures from 19°C to 37°C. In parallel experiments, the temperature was measured inside of the tubers and it could be documented that the treatment described above increased tuber temperature from 19°C to 37°C within 15 to 20 min (data not shown). After 15 min, high-specific-activity [14C]Glc (12.5 GBq/mmol) was injected into a fine borehole through the middle of the tuber as described by Geigenberger et al. (1994), and tubers were incubated for another 45 min at the appropriate temperature until a concentric cylinder (8 mm in diameter) around the borehole was harvested and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Labeled tissue was extracted with 80% (v/v) ethanol at 80°C and reextracted in two subsequent steps with 50% (v/v) ethanol, and the combined supernatants were dried under an air stream at 40°C, taken up in 1 mL of water (soluble fraction), and separated in Suc, Glc, Fru, and ionic components by TLC as described by Geigenberger et al. (1997). The insoluble material left after ethanol extraction was homogenized, taken up in 4 mL of water, and counted for starch. In growing tubers starch accounts for more than 90% of the label in the insoluble fraction (Geigenberger et al., 1994).

Metabolite Analysis

Tubers were incubated in parallel for metabolite analysis. After 45 min of incubation in wet sand at temperatures from 19°C to 37°C, tubers were harvested and cut into small discs (1–2 mm thick), which were placed into liquid N2 immediately. The sampling procedure lasted only a few seconds. The frozen material was homogenized under liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle. An aliquot of the frozen powder (approximately 0.5 g fresh weight) was extracted with TCA (Jelitto et al., 1992), and hexose phosphates, 3PGA, PEP, pyruvate, pyrophosphate, and malate were measured as described by Merlo et al. (1993); isocitrate was measured according to the method of Beutler (1985). The recovery of small, representative amounts of each metabolite through the extraction, storage, and assay procedures has been documented (Hajirezaei and Stitt, 1991; Jelitto et al., 1992). Nucleotides, including UDPGlc, ADPGlc, ATP, and ADP, were measured in TCA extracts by HPLC using a chromatograph (Kontron Instruments, Eching, Germany) fitted with a Partisil-SAX anion-exchange column as described by Geigenberger et al. (1997). Recovery of a small representative amount of ADPGlc during extraction, storage, and analysis has been documented by Geigenberger et al. (1994).

Analysis of Enzyme Activities

Aliquots of the frozen powder (see above) were extracted and spin desalted, and SPS was immediately assayed via the anthrone test as described by Geigenberger et al. (1997). Aliquots of the extract were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and assayed for SuSy, PK, and AGPase as described by Merlo et al. (1993), and for soluble starch synthase according to the method of Jenner et al. (1994).

Respiration Measurements

Immediately after being cut from a growing tuber attached to the plant, potato tuber discs (2 mm thick, 8 mm in diameter) were transferred into the temperature- controlled measuring chamber of an oxygen electrode (Hansatech, King's Lynn, Norfolk, UK) containing 1 mL of buffer solution (10 mm Mes-KOH, pH 6.5), to measure oxygen consumption at 16°C, 21°C, 25°C, 30°C, 33°C, and 37°C.

RESULTS

Elevated Temperatures Inhibit Starch Synthesis and Stimulate Respiration and Suc Resynthesis

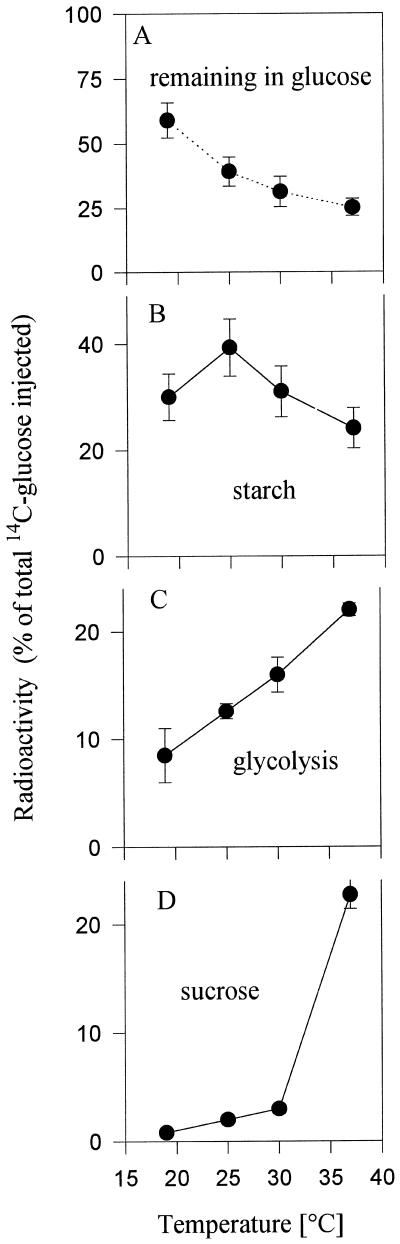

Growing tubers (2–4 g fresh weight) were taken from 6-week-old plants and incubated at 19°C, 25°C, 30°C, and 37°C in wet sand. To measure fluxes, high-specific-activity [14C]Glc was injected into the tubers for 45 min, and the incorporation of label into starch, Suc, and ionic components (cations plus anions) was analyzed. The results are expressed as percentage of the total 14C injected (Fig. 1, A–D). With increasing temperature, an increasing amount of label was metabolized (Fig. 1A). Incorporation of label into starch showed a temperature optimum at 25°C (Fig. 1B), decreasing by 25% and 38% when temperature was increased to 30°C and 37°C, respectively. Compared with this, labeling of ionic components (mainly phosphate ester and organic and amino acids), which is an estimate of flux in glycolysis and respiration, increased with temperatures up to 37°C in a linear manner (Fig. 1C). This was confirmed by an independent approach in which oxygen electrodes were used to measure oxygen consumption in freshly cut potato tuber discs at different temperatures. Oxygen consumption (measured in nmol g−1 fresh weight min−1) was 20.7 ± 1.9, 28.2 ± 1.1, 40.2 ± 3.9, 53.4 ± 1.8, 55.1 ± 1.0, and 62.7 ± 4.5 in discs incubated at 16°C, 21°C, 25°C, 30°C, 33°C, and 37°C, respectively (data are means ± se, n = 4). These data resemble those found in previous work using potato tuber discs (Mohabir and John, 1988), in which an optimum for starch synthesis at 21.5°C was observed, whereas respiration increased in a linear manner up to 30°C.

Figure 1.

Metabolism of [14C]Glc injected into tubers incubated at 19°C, 25°C, 30°C, and 37°C. Growing tubers (2–4 g fresh weight) were taken from 6-week-old plants that had just started to flower, and were incubated immediately in wet sand at different temperatures. After 15 min of preincubation at the temperatures indicated, [14C]Glc was injected into a fine borehole in the middle of the tuber, and tubers were sampled after another 45 min to analyze label remaining in Glc (A), and incorporation of label into starch (B), anions plus cations (glycolysis) (C), and Suc (D). In parallel experiments, the temperature was measured inside the tubers and it could be documented that the above treatment increased tuber temperature from 19°C to 37°C between 15 and 20 min (data not shown). Data are means ± se of four individual tubers.

In potato tubers net Suc degradation is regulated by a cycle of Suc degradation and resynthesis (Geigenberger and Stitt, 1993). To investigate the rate of Suc resynthesis, incorporation of label into Suc was measured (Fig. 1D). Incorporation was low (about 0.8% of total) at 19°C, increased when temperature was increased to 25°C and 30°C, and showed an overproportional increase when tubers were incubated at 37°C. An overproportional increase in the flux back to Suc is indicative of an induction of Suc cycling and reduced net Suc degradation.

Changes of Metabolites

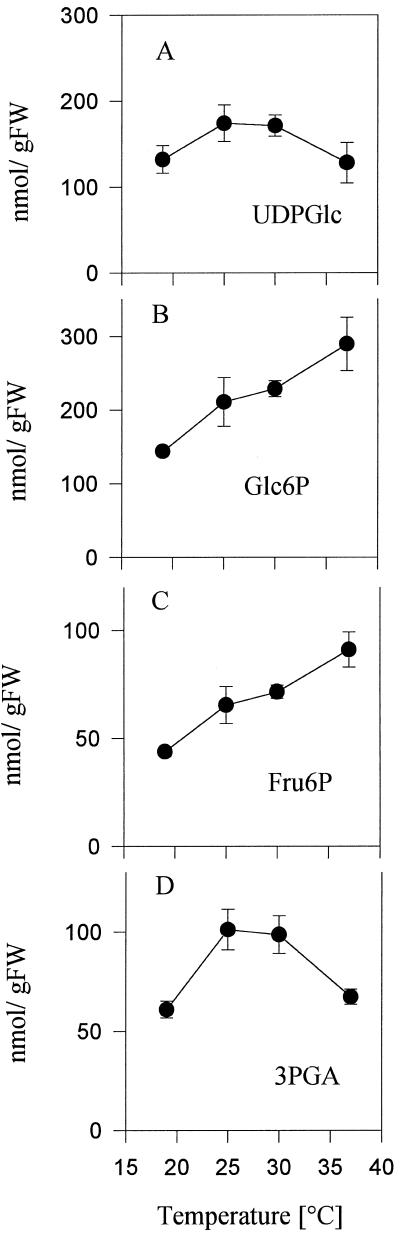

To identify potential sites for regulation, metabolites were measured in tubers of the same experiment (see Fig. 1) incubated in parallel. As the temperature was increased from 19°C to 37°C, Glc-6-P levels increased progressively from 140 to 290 nmol g−1 fresh weight (Fig. 2B). 3PGA levels were low at 19°C, peaked at 25°C, and decreased again in tubers incubated at 37°C (Fig. 2D). The decrease in starch synthesis at elevated temperatures was therefore accompanied by an increase of hexose phosphates and by a decrease of 3PGA (compare Fig. 1B with Fig. 2, B and D). Hexose phosphates are the immediate substrate and 3PGA is a potent activator of potato tuber ADPGlc pyrophosphorylase (Preiss, 1988). No consistent changes were observed in the levels of ATP and ADP (Fig. 3, A and B), UDPGlc (Fig. 2A), or PPi (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Metabolite levels in tubers incubated at 19°C, 25°C, 30°C, and 37°C. Tubers incubated in parallel to those used for radiolabel analysis (see Fig. 1, A–D) were sampled after 45 min for metabolite analysis. A, UDPGlc; B, Glc-6-P; C, Fru-6-P; and D, 3PGA. Data are means ± se of four individual tubers. FW, Fresh weight.

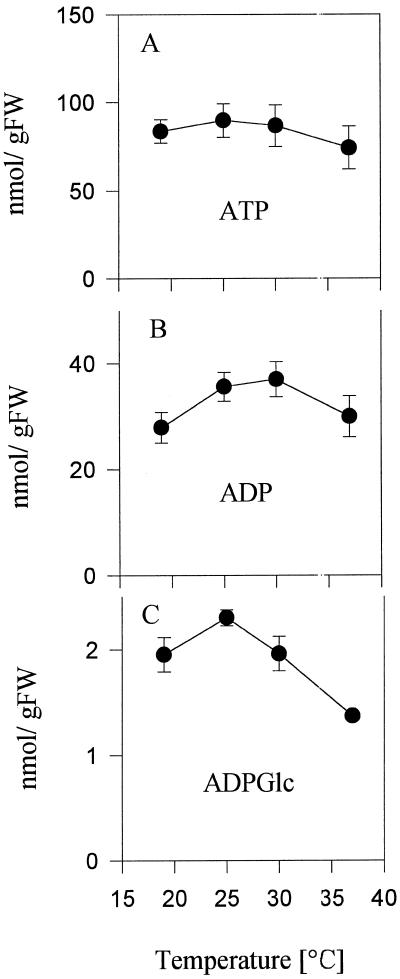

Figure 3.

Levels of adenine nucleotides in tubers incubated at 19°C, 25°C, 30°C, and 37°C. ATP (A), ADP (B), and ADPGlc (C) were measured in the same extracts as in Figure 2. Data are means ± se of four individual tubers. FW, Fresh weight.

Glycolytic and TCA-cycle intermediates were investigated in more detail in a second experiment in which tubers were incubated at 23°C, 32°C, and 37°C (Table I). Labeling data for this experiment also confirmed a decrease in the labeling of starch by 61% and 65% at 32°C and 37°C. Decreased starch synthesis was again accompanied by a 1.6-fold increase in hexose phosphates and an approximately 50% decrease in 3PGA. There was also a 30% decrease in PEP, a slight increase of pyruvate and malate, and a decrease in isocitrate from 21% to 44%. As a result, the PEP/pyruvate ratio declined by 50%. This decrease was accompanied by increased fluxes to carbon dioxide (see above). Together, these results show that there is a direct stimulation of the final respiratory reactions, leading to a drain of TCA-cycle intermediates and a stimulation of reactions converting PEP to pyruvate (PK) or malate (PEPC).

Table I.

Levels of glycolytic intermediates and organic acids, metabolism of [14C]Glc, and enzyme activities in tubers incubated at 23°C, 32°C, and 37°C

| Parameter | 23°C | 32°C | 37°C |

|---|---|---|---|

| % total 14C | |||

| Metabolism of [14C]Glc | |||

| Starch | 40.2 ± 1.9 | 15.7 ± 2.3 | 14.3 ± 1.8 |

| Glycolysis (anions plus cations) | 12.6 ± 1.1 | 20.2 ± 2.6 | 22.2 ± 3.4 |

| Suc | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 11.2 ± 3.1 | 25.6 ± 4.5 |

| nmol g−1 fresh wt | |||

| Metabolites | |||

| Phosphate ester | |||

| Glc-6-P | 130 ± 14 | 213 ± 36 | 205 ± 16 |

| Fru-6-P | 30.8 ± 5.8 | 63.7 ± 13.7 | 60.4 ± 3.1 |

| 3PGA | 80.51 ± 14.3 | 43.3 ± 7.96 | 43.5 ± 2.7 |

| PEP | 22.44 ± 3.47 | 16.6 ± 1.82 | 16.49 ± 1.16 |

| Organic acids | |||

| Pyruvate | 12.00 ± 3.46 | 14.72 ± 5.27 | 20.8 ± 4.03 |

| Malate (μmol g-1 fresh wt) | 11.90 ± 1.28 | 16.08 ± 1.83 | 13.8 ± 0.19 |

| Isocitrate | 75.4 ± 4.3 | 44.7 ± 6.5 | 59.8 ± 8.5 |

| Nucleotides | |||

| ADPGlc | 2.10 ± 0.28 | 0.45 ± 0.15 | 0.32 ± 0.10 |

| nmol g−1 fresh wt min−1 | |||

| Enzymes | |||

| SuSy | 863 ± 41 | 496 ± 148 | 535 ± 243 |

| AGPase | 547 ± 71 | 374 ± 69 | 274 ± 67 |

| Soluble starch synthase | 129 ± 18 | 105 ± 17 | 114 ± 16 |

| PK | 418 ± 33 | 303 ± 48 | 321 ± 41 |

| SPS | |||

| Vmaxa | 493 ± 18 | 401 ± 13 | 391 ± 32 |

| Vselb | 72.7 ± 13.7 | 104 ± 26 | 97.6 ± 12 |

| Vsel/Vmax (%) | 14.6 ± 2.7 | 25.5 ± 5.6 | 24.5 ± 4.1 |

Data are means ± se of four to five individual tubers.

Vmax, Saturating hexose phosphates.

Vsel, Limiting hexose phosphates and inhibitor Pi.

The observed increase in hexose phosphates (Fig. 2, B and C; Table I) indicates a block in starch synthesis. To distinguish between a block at ADPGlc pyrophosphorylase or at the final polymerizing reactions (i.e. starch synthases or branching enzyme) we measured the levels of ADPGlc (Fig. 3C). The level of ADPGlc increased slightly when the temperature was increased to 25°C. ADPGlc decreased by 23% and 45% in tubers incubated at 30°C and 37°C, respectively, which corresponds to the inhibition of starch synthesis at these temperatures (compare Figs. 3C and 1B). Similar trends were obtained in a second experiment (Table I), in which ADPGlc decreased by 78% and 85% in tubers incubated at 32°C and 37°C, respectively. Obviously, inhibition of starch synthesis is not accompanied by an accumulation of ADPGlc, which would be expected if soluble starch synthase were the regulatory site. The observed decrease of ADPGlc was paralleled by a corresponding increase in hexose phosphates, which indicates that the temperature-sensitive site is associated with AGPase.

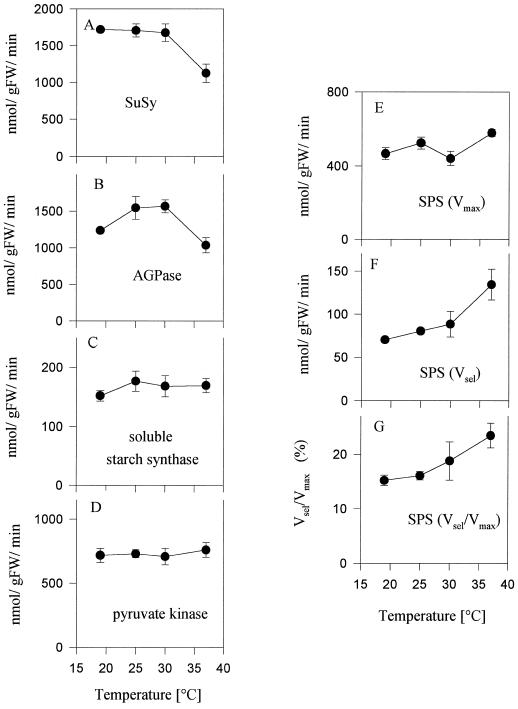

Enzyme Activities

There were no marked changes in the maximal extractable activities of SuSy, AGPase, soluble starch synthase, or PK measured in tubers incubated for 45 min at 19°C, 25°C, and 30°C (Fig. 4, A–D). At 37°C, however, a 40% decline of SuSy (Fig. 4A) and a 27% decrease of AGPase activity (Fig. 4B) were observed. These results were confirmed in a second experiment with a different set of plants (Table I), in which AGPase activity decreased by 32% to 50%, and SuSy activity decreased by 40% in tubers incubated at 32°C and 37°C, whereas soluble starch synthase and PK did not change significantly. In this experiment, tubers were used from older plants (8 weeks old) that had lower levels of enzyme activities compared with the plants from the experiment shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Enzyme activities in tubers incubated at 19°C, 25°C, 30°C, and 37°C. SuSy (A), AGPase (B), soluble starch synthase (C), PK (D), and SPS (E–G) were measured in the same tubers as in Figure 2. SPS was measured under two different assay conditions: (E) Vmax assay (12 mm Fru-6-P, 36 mm Glc-6-P, and 6 mm UDPGlc) or (F) Vsel assay (2 mm Fru-6-P, 6 mm Glc-6-P, 6 mm UDPGlc, and 5 mm Pi). G shows the ratio between the two activities. Data are means ± se of four individual tubers. FW, Fresh weight.

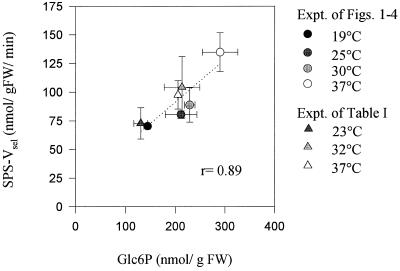

To investigate whether the enhanced resynthesis of Suc was caused by stimulation of SPS, we also determined SPS activity. Activity was measured in two different assay conditions: (a) with saturating hexose phosphates (termed Vmax) to determine changes in maximal activities, and (b) with limiting hexose phosphates and inhibitor Pi (termed Vsel) to determine whether the activation state of the enzyme is modified by covalent modification (Siegl et al., 1990; Huber et al., 1992). Incubation of tubers at elevated temperatures did not have any consistent effect on SPS activity when it was assayed in the presence of saturating hexose-phosphate concentrations (termed the Vmax assay, with 12 mm Fru-6-P, 36 mm Glc-6-P, and 6 mm UDPGlc; Fig. 4E and Table I). However, increasing the temperature up to 37°C led to a 1.5- to 2-fold increase of activity when SPS was assayed in the presence of limiting substrates (termed the Vsel assay, with 2 mm Fru-6-P, 6 mm Glc-6-P, 6 mm UDPGlc, and 5 mm phosphate [Pi]; Fig. 4F and Table I). The increase in Vsel activity was especially marked in tubers exposed to 37°D, and coincided with the stimulation of Suc synthesis and the increase in hexose-phosphate levels (compare Figs. 4F, 1D, and 2B). The Vsel-to-Vmax ratio increased by 1.5- to 1.8-fold (Fig. 4G).

DISCUSSION

In short-term experiments, increasing the temperature from 23°C or 25°C up to 37°C leads to increased respiration, decreased starch synthesis, and increased resynthesis of Suc in growing potato tubers. Similar changes of fluxes in response to elevated temperature were also seen in previous studies on potato tuber discs (Mohabir and John, 1988), but these earlier studies did not provide in vivo information about the changes of metabolites to allow the reasons for the inhibition of starch synthesis to be identified.

Elevated Temperatures Lead to Increased Respiration, with the Resulting Decline in 3PGA Leading to Inhibition of AGPase and Starch Synthesis

The increase in respiration at high temperatures was accompanied by a 30% to 50% decrease of PEP and 3PGA, and a 50% decrease in the PEP-to-pyruvate ratio (Fig. 2; Table I). The increased rate of glycolysis can therefore be attributed to activation of PK and/or PEPC. Similar results have been obtained when respiration increased in response to other factors, including increased carbohydrate levels (Geigenberger and Stitt 1991a; Hatzfeld and Stitt, 1991; Geiger et al., 1998), addition of Gln or ammonia (Geigenberger and Stitt, 1991b), or addition of uncouplers (Hatzfeld and Stitt, 1991).

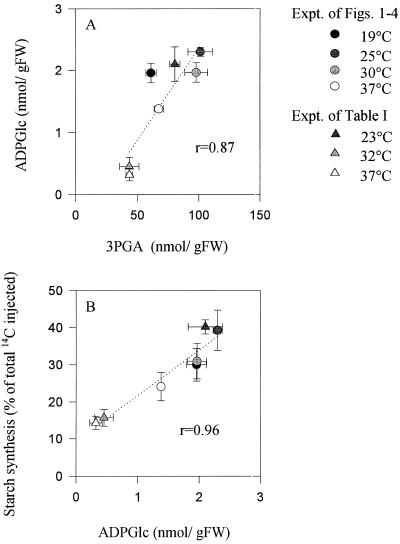

Potato tuber AGPase is allosterically activated by 3PGA (Sowokinos, 1981; Sowokinos and Preiss, 1982). The decrease in the level of 3PGA should therefore lead to an inhibition of AGPase. In agreement, the decrease in 3PGA at high temperature led to a decrease in ADPGlc and to an inhibition of starch synthesis (Fig. 5, A and B). We conclude that after activation of glycolysis caused by increased respiration, a decrease of 3PGA leads to inhibition of AGPase, and restricts the rate of starch synthesis. It must be noted, however, that the reported 3PGA levels are overall levels present in both the cytoplasm and the amyloplasts. Direct measurements of subcellular metabolite levels will be needed to confirm our interpretation.

Figure 5.

Relation between 3PGA and ADPGlc (A) and ADPGlc and starch synthesis (B) in tubers exposed to different temperatures. Data are taken from Figures 1–3 and Table I, and are means ± se of four individual tubers. FW, Fresh weight; Expt., experiment.

Hexose phosphates increased at elevated temperatures (Fig. 2; Table I), demonstrating that the inhibition of starch synthesis is caused by a direct inhibition of AGPase, rather than to a shortage of a substrate (i.e. via a block in Suc degradation). The decline of PEP and 3PGA (see above) would be expected to activate phosphofructokinase (Dennis and Greyson, 1987) and Fru-6-P2-kinase, leading to increased Fru-2,6-bisP and activation of PFP (Stitt, 1990), and this should stimulate the entry of hexose phosphates into glycolysis. The finding that hexose phosphates increase implies that the regulatory loop leading to the stimulation of phosphofructokinase and PFP is not strong enough to lead to a decrease in hexose-phosphate levels when respiration and glycolysis is stimulated by increasing temperature. A similar result was obtained when respiration and glycolysis increased in response to an increased supply of carbohydrates (Geigenberger and Stitt, 1991a; Hatzfeld and Stitt, 1991; Geiger et al., 1998), addition of Gln or ammonia (Geigenberger and Stitt, 1991b), or addition of uncouplers (Hatzfeld and Stitt, 1991). An alternative explanation for the increased hexose-phosphate levels would be that starch degradation is stimulated in response to high temperatures. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of starch turnover in the regulation of starch synthesis in potato tubers.

Our results do not reveal the reasons for the stimulation of respiration at high temperatures. When temperature is increased, a general increase in the velocity of enzyme activities or chemical reactions is to be expected and could lead to increased flux into the respiratory pathways (Lambers, 1985). On the other hand, elevated temperatures will lead to increased membrane permeability, which impairs transport processes and increases energy costs to maintain membrane gradients. However, there were no consistent changes in the overall levels of ATP or ADP in the tubers in response to temperature that could be indicative of a stimulation of respiration attributable to an increased demand for ATP (Fig. 3). Increased respiration led to decreased isocitrate levels in the mitochondria (Table I), indicating a drain in TCA cycle intermediates caused by stimulation of the final oxidation process at the mitochondrial membrane in response to high temperatures. This was accompanied by activation of PK and/or PEPC and increased supply of substrates for the TCA cycle. Accumulation of pyruvate and malate could also indicate that transport of substrates into the mitochondria is a limiting factor at elevated temperatures.

There was a 28% to 50% decrease in AGPase and a 40% to 50% decrease in SuSy activity measured under optimal conditions in extracts from tubers exposed to high temperatures (Fig. 4; Table I). Similar results were also obtained in previous experiments with potato tubers (Kraus and Marschner, 1984; Lafta and Lorenzen, 1995). It is very unlikely that the 50% decrease in the amount of AGPase or SuSy activities is responsible for the short-term inhibition of starch synthesis, since a similar decrease in enzyme activity in tubers with reduced expression of AGPase (Müller-Röber et al., 1992) or SuSy (Zrenner et al., 1995) due to antisense did not alter starch accumulation. However, changes in the amount of enzymes could amplify the effect of fine control mechanisms acting in parallel, leading to a higher degree of metabolic control. More studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms leading to the high-temperature-induced decrease in enzyme activity and to determine if they lead to a further inhibition of starch synthesis during a more prolonged exposure to high temperatures.

Inhibition of Starch Synthesis Is Accompanied by a Stimulation of Suc Synthesis Caused by Increased Hexose-Phosphate Levels and Activation of SPS

The inhibition of starch synthesis was accompanied by an accumulation of hexose phosphates (Fig. 2, B and C; Table I) and an overproportional increase of Suc resynthesis (Fig. 1D). Two factors could be responsible for the stimulation of Suc synthesis. First, potato tuber SPS is subject to allosteric activation by Glc-6-P and inhibition by Pi (Reimholz et al., 1994). Second, elevated temperatures led to increased activation of SPS, which is expressed as a change in its kinetic properties, which allows higher SPS activity in the presence of limiting substrate concentrations (Fig. 4, F and G). This resembles the effect of increased rates of photosynthesis on leaf SPS phosphorylation (Huber and Huber, 1996). In the leaf system SPS is activated by dephosphorylation and SPS kinase is shown to be inhibited by hexose phosphates (McMichael et al., 1995). As shown in Figure 6, the increase in SPS activity assayed under selective conditions correlates with increased Glc-6-P levels in potato tubers incubated at different temperatures. Accumulation of hexose phosphates in response to decreased starch synthesis was also observed in tubers with reduced expression of AGPase via antisense (R.N. Trethewey, P. Geigenberger, A. Hennig, H. Notter-Fleisch, and L. Willmitzer, unpublished results). Also in this case, a 2-fold increase in hexose phosphates was accompanied by a 2-fold increase in SPS activation (Geigenberger et al., 1995; P. Geigenberger, unpublished results). In potato tubers Suc mobilization is regulated by a cycle of Suc synthesis and degradation (Geigenberger and Stitt, 1993; Geigenberger et al., 1995, 1997). The overproportional increase of Suc resynthesis at 37°C (Fig. 1D; Table I) is indicative of an induction of Suc cycling and reduced net Suc degradation. This was paralleled by a 40% decrease in SuSy activity measured in tubers incubated at 37°C (Fig. 4A; Table 1).

Figure 6.

Relation between the Glc-6-P level and the activity of SPS measured in the Vsel assay with limiting substrates and phosphate. Data are taken from Figures 2A and 4F and Table I, and are means ± se of four individual tubers. FW, Fresh weight; Expt., experiment.

Role of AGPase in the Control of Starch Synthesis in Potato Tubers

In potato tubers an 80% to 95% reduction of AGPase expression led to decreased rates of starch accumulation (Müller-Röber et al., 1992), whereas recent studies indicate that reducing soluble starch synthase to 20% of the wild-type level has no effect on starch accumulation (Marshall et al., 1996). This indicates the importance of AGPase, rather than soluble starch synthase, in controlling the rate of starch synthesis under normal growth conditions in potato tubers. Under extreme water stress, the effect of starch synthases on the flux to starch increases, which is indicated by changes in ADPGlc levels (Geigenberger et al., 1997). This, however, does not seem to be the case at high temperatures in tubers (see above).

Our data indicate the importance of metabolic fine control of AGPase for the regulation of starch synthesis in potato tubers. A similar interaction of 3PGA with AGPase activity and starch synthesis is found in transgenic potato tubers with decreased expression of PFP (Hajirezaei et al., 1994) or of NAD-malic enzyme (H.L. Jenner, B.M. Winning, C.J. Leaver, and S.A. Hill, unpublished data), and in wild-type tubers in response to moderate water stress (Geigenberger et al., 1997), or in leaves in response to water stress (Quick et al., 1989) or a decreased availability of fixed carbon (Stitt, 1990). This confirms previous studies on potato tubers overexpressing native and mutated Escherichia coli AGPase (Stark et al., 1992), demonstrating the significance of the allosteric properties of AGPase for the rate of starch accumulation.

The Effect of High Temperature on Starch Accumulation in Cereals

High temperature during the grain-filling process is also yield limiting in cereals, leading to a reduction in starch deposition and grain size (Chowdhury and Wardlaw, 1978) caused by an impaired conversion of Suc to starch (Bhullar and Jenner, 1986; MacLeod and Duffus, 1988). The reasons for this adverse effect of temperature on starch synthesis have been extensively studied in wheat endosperm.

In short-term experiments, isolated grains were heated at temperatures up to 40°C for 1 to 4 h (Jenner et al., 1993) or 3 h (Keeling et al., 1993) to analyze enzyme activities and the flux of [14C]Suc or Glc to starch. In the study by Jenner et al. (1993), a sharp decline of soluble starch synthase was observed after 30 min of exposure to 35°C, and a further but smaller reduction occurred after 2 and 4 h. After 2 h at 35°C a significant but smaller reduction of AGPase was also observed, whereas SuSy activity remained unchanged. A similar decrease of soluble starch synthase was also observed by Keeling et al. (1993), although in this study no significant changes in AGPase, SuSy, or UGPase were observed in the 3-h incubation period. In both of these studies, the decrease of extracted soluble starch synthase observed at elevated temperatures was highly correlated with the decrease in the rate of starch synthesis (Jenner et al., 1993; Keeling et al., 1993). High temperatures also led to a marked change in the kinetic properties of starch synthase extracted from wheat endosperm, leading to a loss of cooperativity between glucans and ADPGlc (Jenner et al., 1995).

This decrease in starch synthase activity was also seen in long-term experiments. When wheat ears were exposed to 35°C for 1 to 9 d, soluble starch synthase activity was reduced by more than 50% and AGPase was decreased by about 26% (Hawker and Jenner, 1993). In a previous study (Jenner, 1991), metabolite levels were analyzed in wheat ears exposed to elevated temperatures for up to 7 d to identify temperature-sensitive steps in the conversion of Suc to starch. Increasing the temperature from 16°C/21°C to 25°C/35°C (night/day) resulted in a decrease in the levels of metabolites (hexose phosphates, UDPGlc, and ADPGlc), whereas the Suc content of the endosperm was either not affected or increased (Jenner, 1991). Hexose phosphates declined by 50% after 1 d and remained at a constant low level for the next 6 d. UDPGlc and ADPGlc decreased more gradually during the entire time interval, being significantly reduced by 28% and 13%, respectively, compared with the low-temperature control. The overall decrease in metabolite levels in wheat during long-term exposure to heat indicates that there may be additional factors besides an inhibition of starch synthase that contribute to the small increase in starch deposition with increasing temperature.

In potato tubers elevated temperatures lead to a decrease in the extracted amounts of SuSy and AGPase, and to inhibition of AGPase due to decreased levels of 3PGA (see above), both mechanisms acting in concert and leading to an inhibition of starch synthesis. In wheat, however, inhibition of starch synthesis at elevated temperatures is associated with a decrease in the extracted amount of soluble starch synthase (see above). This might reflect different roles of AGPase and starch synthases in controlling flux to starch in cereals such as wheat or barley compared with potato (Jenner and Hawker, 1993). In wheat or barley endosperm, for example, AGPase is less sensitive to 3PGA activation than in potato tubers (Jenner and Hawker, 1993; Kleczkowski et al., 1993), and at least for barley it could be shown that a considerable part of the AGPase activity is located outside of the plastid (Thorbjornsen et al., 1996).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to Steven Hill (Oxford, UK) for discussions and for making unpublished data available.

Abbreviations:

- ADPGlc

adenine diphosphoglucose

- AGPase

adenine diphosphoglucose pyrophosphorylase

- PEPC

PEP carboxylase

- PFP

pyrophosphate:Fru-6-P phosphotransferase

- 3PGA

glycerate-3-phosphate

- PK

pyruvate kinase

- SPS

Suc phosphate synthase

- SuSy

Suc synthase

- UDPGlc

uridine diphosphoglucose

- UGPase

uridine diphosphoglucose pyrophosphorylase

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 199).

LITERATURE CITED

- Awan AB. Influence of mulch on soil moisture, soil temperature and yield of potatoes. Am Potato J. 1964;41:337–339. [Google Scholar]

- Berry J, Björkman O. Photosynthetic response and adaptation to temperature in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1980;31:491–543. [Google Scholar]

- Beutler HO (1985) Isocitrate. In H Bergmeyer, ed, Methods of Enzymatic Analysis, Ed 3, Vol 7. Verlag Chemie, Weinheim, Germany, pp 13–19

- Bhullar SS, Jenner CF. Effects of temperature on the conversion of sucrose to starch in the developing wheat endosperm. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1986;13:605–615. [Google Scholar]

- Burton W (1986) The Potato, Ed 3. Longman Scientific and Technical, Harlow, UK

- Chowdhury SI, Wardlaw IF. The effect of temperature on kernel development in cereals. Aust J Agric Res. 1978;29:205–223. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis DT, Greyson M. Fructose-6-phosphate metabolism in plants. Physiol Plant. 1987;69:395–404. [Google Scholar]

- Farrar JF, Williams JM. The effects of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide and temperature on carbon partitioning, sink-source relations and partitioning. Plant Cell Environ. 1991;14:813–830. [Google Scholar]

- Geigenberger P, Krause K-P, Hill LM, Reimholz R, MacRae E, Quick P, Sonnewald U, Stitt M (1995) The regulation of sucrose synthesis in the leaves and tubers of potato plants. In HG Pontis, GL Salerno, EJ Echeverria, eds, Sucrose Metabolism, Biochemistry, Physiology and Molecular Biology, Vol 14. American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville, MD, pp 14–24

- Geigenberger P, Merlo L, Reimholz R, Stitt M. When growing potato tubers are detached from their mother plant there is a rapid inhibition of starch synthesis, involving inhibition of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Planta. 1994;193:486–493. [Google Scholar]

- Geigenberger P, Reimholz R, Geiger M, Merlo L, Canale V, Stitt M. Regulation of sucrose and starch metabolism in potato tubers in response to short-term water deficit. Planta. 1997;201:502–518. [Google Scholar]

- Geigenberger P, Stitt M. A “futile” cycle of sucrose synthesis and degradation is involved in regulating partitioning between sucrose, starch and respiration in cotyledons of germinating Ricinus communis L. seedlings when phloem transport is inhibited. Planta. 1991a;185:81–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00194518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geigenberger P, Stitt M. Regulation of carbon partitioning between sucrose and nitrogen assimilation in cotyledons of germinating Ricinus communis L. seedlings. Planta. 1991b;185:563–568. doi: 10.1007/BF00202967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geigenberger P, Stitt M. Sucrose synthase catalyses a readily reversible reaction in vivo in developing potato tubers and other plant tissues. Planta. 1993;189:329–339. doi: 10.1007/BF00194429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger M, Stitt M, Geigenberger P (1998) Metabolism in potato tuber slices responds differently after addition of sucrose and glucose. Planta (in press)

- Hajirezaei M, Sonnewald U, Viola R, Carlisle S, Dennis D, Stitt M. Transgenic potato plants with strongly decreased expression of pyrophosphate:fructose-6-phosphate phosphotransferase show no visible phenotype and only minor changes in metabolic fluxes in their tubers. Planta. 1994;192:16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hajirezaei MR, Stitt M. Contrasting roles for pyrophosphate:fructose-6-phosphate phosphotransferase during aging of tissues from potato tubers and carrot storage tissues. Plant Sci. 1991;77:177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzfeld W-D, Stitt M. Regulation of glycolysis in heterotrophic cell suspension cultures of Chenopodium rubrum in response to proton fluxes at the plasmalemma. Physiol Plant. 1991;81:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hawker JS, Jenner CF. High temperature affects the activity of enzymes in the committed pathway of starch synthesis in developing wheat endosperm. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1993;20:197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Huber SC, Huber JL. Role and regulation of sucrose phosphate synthase in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:431–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber SC, Huber JLA, McMichael RW (1992) The regulation of sucrose synthesis in leaves. In CJ Pollock, JF Farrar, AJ Gordon, eds, Carbon Partitioning within and between Organisms. BIOS Scientific Publishers, Oxford, UK, pp 1–26

- Jellito T, Sonnewald U, Willmitzer L, Hajirezaei MR, Stitt M. Inorganic pyrophosphate content and metabolites in leaves and tubers of potato and tobacco plants expressing E. coli pyrophosphatase in their cytosol. Planta. 1992;188:238–244. doi: 10.1007/BF00216819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner CF. Effects of exposure of wheat ears to high temperature on dry matter accumulation and carbohydrate metabolism in the grain of two cultivars. I. Immediate responses. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1991;18:165–177. [Google Scholar]

- Jenner CF, Denyer K, Guerin J. Thermal characteristics of soluble starch synthase from wheat endosperm. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1995;22:703–709. [Google Scholar]

- Jenner CF, Denyer K, Hawker JS. Caution on the use of the generally accepted methanol precipitation technique for the assay of soluble starch synthase in crude extracts of plant tissues. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1994;21:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jenner CF, Hawker JS. Sink strength: soluble starch synthase as a measure of sink strength in wheat endosperm. Plant Cell Environ. 1993;16:1023–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Jenner CF, Siwek K, Hawker JS. The synthesis of [14C]starch from [14C]sucrose in isolated wheat grains is dependent upon the activity of soluble starch synthase. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1993;20:329–335. [Google Scholar]

- Keeling PL, Bacon PJ, Holt DC. Elevated temperature reduces starch deposition in wheat endosperm by reducing the activity of soluble starch synthase. Planta. 1993;191:342–348. [Google Scholar]

- Kleczkowski LA, Villand P, Lüthi E, Olsen OD, Preiss J. Insensitivity of barley endosperm ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase to 3-phosphoglycerate and orthophosphate regulation. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:179–186. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus A, Marschner H. Growth rate and carbohydrate metabolism of potato tubers exposed to high temperatures. Potato Res. 1984;27:297–303. [Google Scholar]

- Lafta AM, Lorenzen JH. Effect of high temperature on plant growth and carbohydrate metabolism in potato. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:637–643. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.2.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambers H. Respiration in intact plants and tissues. In: Douce R, Day DA, editors. Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology, Vol 18. Berlin: Springer; 1985. pp. 418–473. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod LC, Duffus CM. Reduced starch content and sucrose synthase activity in developing endosperm of barley plants grown at elevated temperatures. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1988;15:367–375. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J, Sidebottom C, Debet M, Martin C, Smith A, Edwards A. Identification of the major soluble starch synthase in the soluble fraction of potato tubers. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1121–1135. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMichael RW, Jr, Bachmann M, Huber SC. Spinach leaf sucrose-phosphate synthase and nitrate reductase are phosphor-ylated and inactivated by multiple protein kinases in vitro. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:1077–1082. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.3.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlo L, Geigenberger P, Hajirezaei MR, Stitt M. Changes of carbohydrates, metabolites and enzyme activities in potato tubers during development, and within a single tuber along a stolon-apex gradient. J Plant Physiol. 1993;142:392–402. [Google Scholar]

- Midmore DJ, Prange RK. Growth responses of two Solanum species to contrasting temperatures and irradiance levels. Ann Bot. 1992;69:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mohabir G, John P. Effect of temperature on starch synthesis in potato tuber tissue and in amyloplasts. Plant Physiol. 1988;88:1222–1228. doi: 10.1104/pp.88.4.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Röber BT, Sonnewald U, Willmitzer L . Inhibition of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase leads to sugar storing tubers and influences tuber formation and expression of tuber storage protein genes. EMBO J. 1992;11:1229–1238. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preiss J. Biosynthesis of starch and its regulation. In: Preiss J, editor. The Biochemistry of Plants, Vol 14. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 181–254. [Google Scholar]

- Quick P, Siegl G, Neuhaus HE, Feil R, Stitt M. Short-term water stress leads to a stimulation of sucrose synthesis by activating sucrose phosphate-synthase. Planta. 1989;177:536–546. doi: 10.1007/BF00392622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimholz R, Geigenberger P, Stitt M. Sucrose-phosphate synthase is regulated via metabolites and protein phosphorylation in potato tubers, in a manner analogous to the enzyme in leaves. Planta. 1994;192:480–488. [Google Scholar]

- Siegl G, MacKintosh C, Stitt M. Sucrose-phosphate synthase is dephosphorylated by protein phosphatase 2A in spinach leaves: evidence from the effects of okadaic acid and microcystin. FEBS Lett. 1990;270:198–202. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81267-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowokinos JR. Pyrophosphorylases in Solanum tuberosum. II. Catalytic properties and regulation of ADP-glucose and UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase activities in potatoes. Plant Physiol. 1981;68:924–929. doi: 10.1104/pp.68.4.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowokinos JR, Preiss J. Pyrophosphorylases in Solanum tuberosum. III. Purification, physical, and catalytic properties of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in potatoes. Plant Physiol. 1982;69:1459–1466. doi: 10.1104/pp.69.6.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark DM, Timmermann KP, Barry GF, Preiss J, Kishore GM. Regulation of the amount of starch in plant tissues by ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Science. 1992;258:287–292. doi: 10.1126/science.258.5080.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M. Fructose-2,6-bisphosphate as a regulatory molecule in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1990;41:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Thorbjornsen T, Villand P, Denyer K, Olsen OA, Smith AM. Distinct isoforms of ADPglucose pyrophosphorylase occur inside and outside the amyloplast in barley endosperm. Plant J. 1996;10:243–250. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S, Marani A, Rudich J. Effect of temperature and photoperiod on assimilate partitioning in potato plants. Ann Bot. 1990;64:241–247. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S, Marani A, Rudich J. Effect of temperature on carbohydrate metabolism in potato plants. J Exp Bot. 1991;42:619–625. [Google Scholar]

- Zrenner R, Salanoubat M, Willmitzer L, Sonnewald U. Evidence of the crucial role of sucrose synthase for sink strength using transgenic potato plants. Plant J. 1995;7:97–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.07010097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]