Abstract

We present survival, neurological function, and complications in a consecutive series of 282 patients operated for spinal metastases from January 1990 to December 2001. Our main surgical indication throughout this time period was neurological deficit rather than pain. Metastases from cancer of the prostate accounted for 40%, breast 15%, kidney 8%, and lung 7%. In 78% the level of decompression was thoracic and lumbar in 22%. Thirteen percent had a single metastases only, 64% had multiple skeletal metastases, and 23% had non-skeletal metastases also. Preoperatively 64% were non-walkers (Frankel A-C), 30% could walk with aids (Frankel D) and 8% had normal motor function (Frankel E). Posterior decompression and stabilization was applied in 212 patients, 47 had laminectomy only, and 23 had anterior decompressions and reconstruction. Complications were recorded at a level of 20%, and systemic complications were often associated with early death. The survival rate was 0.63 at 3 months, 0.47 at 6 months, 0.30 at 1 year, and 0.16 at 2 years. Twelve of 255 (5%) patients with motor deficits were worsened postoperatively, whereas 179 (70%) improved at least one Frankel grade. The ability to walk postoperatively was retained during follow-up in more than 80% of the patients. This study shows that important improvement of function can be gained by surgical treatment, but the complication rate was high and many patients died of their disease within the first months of surgery.

Keywords: Paraplegia-paraparesis, Spine surgery, Palliation, Survival, Bone metastases

Introduction

Surgical treatment, based on decompression of the spinal cord together with restoration of spinal stability, may reduce pain and reestablish function in cancer patients with spinal metastases [1, 2, 9, 10, 17]. The treatment is purely palliative and will not affect prognosis and must be weighted against other palliative treatment options [3]. There are, therefore, major problems in selecting patients for surgery. Factors of relevance when choosing between surgery and other treatment modalities include: the extent of pain, the neurological deficit, the primary tumor’s sensitivity to radio- or chemotherapy, the dissemination of the disease, and the general condition of the patient. Furthermore, spinal instability and the technical feasibility of surgical decompression and stabilization need to be taken into account.

The indication for surgery may be neurological deficit, or pain without epidural compression of the spinal cord or cauda equina. If there is major neurological deficit, only surgery will reliably and quickly restore function [11, 14]. However, if pain is the major problem, surgery is only one of several treatment options, and the cost-benefit ratio for the patient may be more dubious.

We present a consecutive series of spinal metastases patients operated on at our department during a 12-year period. Our main surgical indication throughout this time period has been neurological deficit rather than pain. This patient series differs from most other studies as regards indications for surgery, primary tumor types and survival [19, 23]. We present survival, neurological function, and complications in 282 patients with thoracic or lumbar spinal metastases.

Patients and methods

A total of 284 consecutive patients, operated from January 1990 to December 2001, for spinal metastases surgery were followed prospectively at our Department. Previously published results for the first 67 patients operated on up until 1994 were included in the present study [2]. Two foreign patients returned home 1 week after the operation, leaving 282 patients for analysis. There were 69% men and 31% women, and the median age was 66 (23–93) years.

The most common origin was cancer of the prostate in 40%, followed by breast 15%, kidney 8%, and lung 7% (Table 1). For the 243 patients who presented with a known cancer, a median interval of 2 (0.1–26) years had elapsed since the diagnosis of the primary tumor. The median interval differed among the cancer types; i.e., 0.4 year for lung cancer, 1 year for kidney cancer, 3 years for prostate cancer and 6 years for breast cancer. Forty-three (15%) patients did not have a history of cancer at the time of presentation. In ten of these the diagnosis was established preoperatively by fine needle aspiration biopsy for cytology [21]. In the remaining patients, the diagnosis was established by histopathological examination of surgical samples. Among these 43 patients, the most common origins were the prostate in 13, lung in seven and kidney in six, whereas in nine the origin remained unknown.

Table 1.

Origin of primary tumor

| Site | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Prostate | 114 | 40 |

| Breast | 41 | 15 |

| Kidney | 23 | 8 |

| Lung | 19 | 7 |

| Myeloma | 15 | 5 |

| Colon | 14 | 5 |

| Genito-urinary | 12 | 4 |

| Unknown primary | 11 | 4 |

| Melanoma | 8 | 3 |

| Sarcoma | 6 | 2 |

| Lymphoma | 3 | 1 |

| Thyroid | 2 | 1 |

| Others | 13 | 5 |

| Total | 282 | 100 |

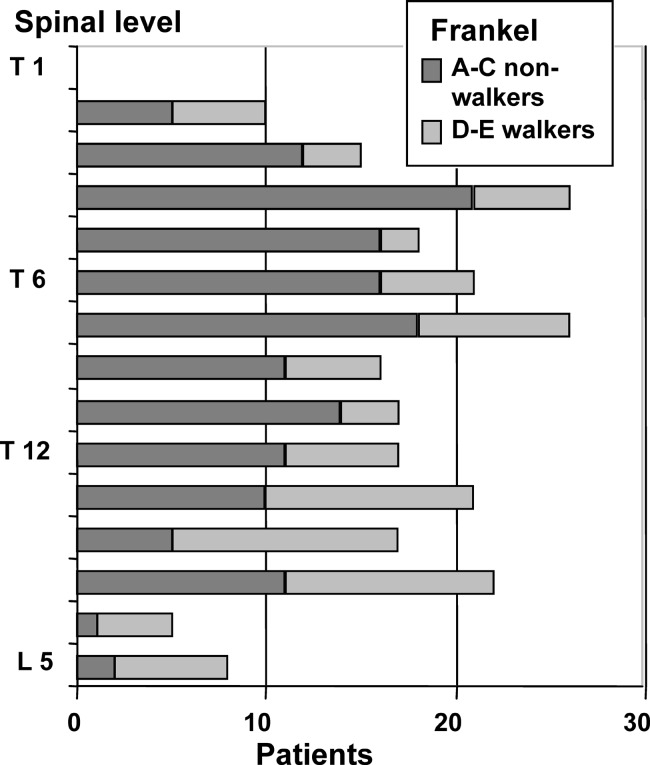

Pathological fracture was seen in 55% of the cases. In 78% the level of decompression was thoracic and lumbar in 22% (Fig. 1). As assessed upon presentation, 77% had only bone metastases and 23% had non-skeletal metastases also (lung, liver, lymph node or brain metastases). Among those with only bone metastases, 17% had a single vertebral metastasis only and 83% had two or more bone metastases to the spine or other bones.

Fig. 1.

Graph showing level of epidural compression and severity of neurological deficit in 282 patients. The midthoracic level was most common and was also associated with more severe neurological deficits, compared with the lumbar level

Neurological function was assessed by applying the Frankel classification of motor and sensory compromise [6, 8]. Preoperatively the distribution of neurological deficit was: Frankel A 3% (complete paraplegia), B 9% (no motor function), C 52% (motor function useless), D 30% (slight motor function deficit), E 8% (no motor deficit). The neurological function was assessed within 2 weeks postoperatively, and then at approximately 3-monthly intervals during the first year, and then once yearly.

Surgery

Posterior decompression and stabilization was the mainstay treatment and applied in 212 patients. In 47 patients the spinal cord or cauda equina was decompressed only, and in 23 anterior decompression with reconstruction of the vertebral body was applied. None had combined procedures, i.e., both anterior and posterior stabilization.

For posterior stabilization with rods, we used hooks only in 60%, pedicle screws in 26% and mixed in 14%. Many different types of implants were used during these 12 years; we started with CD, followed by Isola, then Synergy, and now use USS. Augmentation with methyl methacrylate was only used in 11 cases; bone grafts were not used, and we never prescribed external supports postoperatively. For anterior reconstruction we always used bone cement to replace the destroyed vertebral body, and for instrumentation Z-plates or Synergy rods.

Patients were operated during day time in 90% and at night in 10%. The median operating time was 3 h (0.5–8 h), and the median blood loss 1,500 ml (100–16,500 ml). There was no difference in blood loss or operating time between posterior and anterior stabilization.

Survival

The duration of postoperative survival was considered to be the time between the date of the operation and the latest follow-up examination (September 2003) or death. One patient moved abroad after 7 months and was lost to follow-up. Survival estimates were calculated according to the methods of Kaplan and Meier [5].

Results

Complications

A total of 60 complications were recorded in 56 (20%) of the 282 patients. Systemic complications were seen in 13 and were often associated with early death (Table 2). Forty-nine patients had local complications (Table 3). Wound infections were seen in 34, of which nine were operated with wound revision. Two infections presented late, one after 3 years in a patient with myeloma and the other after 7 years in a patient with lymphoma. Two of 19 patients with a thoracotomy developed pleural exudates needing drainage. Two patients with epidural compression at T3 and T4, respectively, were decompressed at the wrong level, and were reoperated the following day. One remained paraplegic, the other regained normal motor function and survived 6 years.

Table 2.

Systemic complications

| Type of complication | n | Time to death |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac; infarction or congestive | 5 | 1, 2, 5, 10 and 12 days |

| Pulmonary; pneumonia | 2 | 14 and 30 days |

| Thromboembolic; deep venous trombosis, stroke | 2 1 |

3 and 15 months alive 9 years |

| Gastrointestinal; bleeding ulcer | 1 | 30 days |

| Septicemia | 2 | 14 days and 3 months |

Table 3.

Local complications

| Type of complication | n | Revised |

|---|---|---|

| Infection | 34 | 9 (2 late at 3 and 7 years) |

| Hematoma | 5 | 2 |

| Wound dehiscence | 1 | 1 |

| Dural tear | 3 | 1 |

| Pleural exudate (anterior approach) | 2 | 2 pleurascentesis |

| Wrong level decompressed | 2 | 2 |

| Misplaced screw/hook | 2 | 1 |

Long duration of surgery and high blood loss increased the rate of postoperative infection. Hence, those operated for more than 4 h had a threefold increased rate of infection and a blood loss of more than 3,000 ml had a twofold increase.

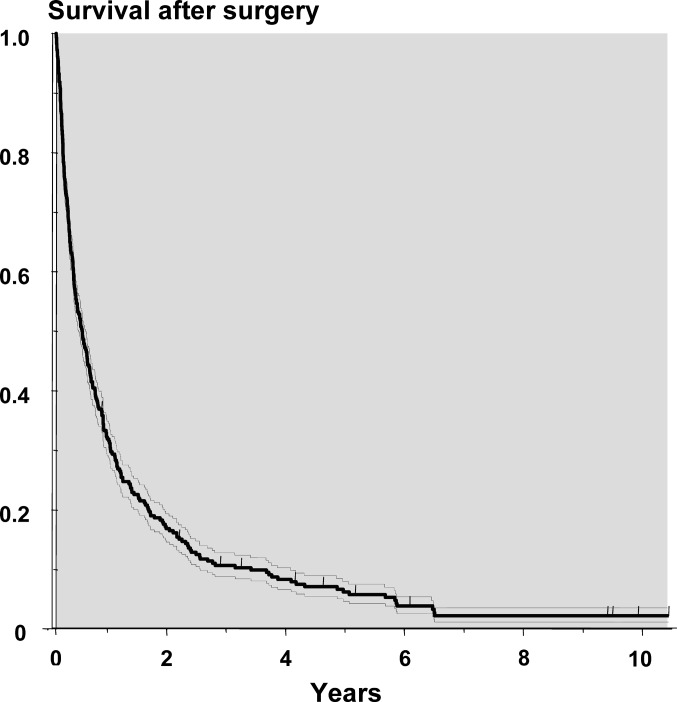

Survival

A total of 37 (13%) of the 282 patients died within 30 days of the operation. The rate of survival was 0.63 at 3 months, 0.47 at 6 months, 0.30 at 1 year, 0.16 at 2 years, and 0.05 at 5 years (Fig. 2). Neither the short nor the long-term survival has improved comparing patients operated in the first years of the study to those of the last years. The 30 days mortality rate was not related to the extent of metastatic disease, but at 3 months the survival rate was 0.50 for patients with non-skeletal metastases, compared with 0.81 for those with a solitary skeletal metastasis (Table 4). Furthermore, none of the 65 patients with non-skeletal metastases survived 2 years. The 2-year survival rate for those with multiple skeletal metastases was 0.16 compared with 0.37 with a solitary metastasis. Survival was neither related to sex nor age. The group of patients who had undergone anterior procedures had a higher survival rate at one and 2 years than those operated through a posterior approach.

Fig. 2.

Survival curve based on all 282 patients operated. Dotted lines denote standard errors, tick-marks censored patients

Table 4.

Survival

| Patients | 3 months | 1 year | 2 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 282 | 0.63 | 0.28 | 0.16 |

| Extent of metastases | ||||

| Single skeletal | 37 | 0.81 | 0.45 | 0.36 |

| Multiple skeletal | 180 | 0.63 | 0.31 | 0.16 |

| Non-skeletal metastases | 65 | 0.53 | 0.11 | 0.04 |

| Type of surgery | ||||

| Laminectomy | 47 | 0.57 | 0.28 | 0.20 |

| Posterior stabilization | 212 | 0.63 | 0.26 | 0.13 |

| Anterior stabilization | 23 | 0.78 | 0.48 | 0.30 |

| Origin of primary tumor | ||||

| Prostate, previously undiagnosed | 13 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.62 |

| known cancer | 101 | 0.63 | 0.26 | 0.10 |

| Breast | 41 | 0.73 | 0.41 | 0.30 |

| Lung | 19 | 0.33 | 0.06 | 0 |

| Myeloma/lymphoma | 18 | 0.83 | 0.56 | 0.39 |

| Kidney | 23 | 0.60 | 0.23 | 0.09 |

| Function preoperatively | ||||

| Non-walkers (Frankel A-C) | 172 | 0.58 | 0.25 | 0.15 |

| Walkers (Frankel D-E) | 110 | 0.70 | 0.33 | 0.18 |

| Patological fracture | ||||

| Yes | 157 | 0.62 | 0.28 | 0.12 |

| No | 124 | 0.64 | 0.29 | 0.20 |

| History of known cancer | ||||

| Yes | 239 | 0.61 | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| No | 43 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 0.37 |

The postoperative survival was not related to the preoperative neurological function. Hence, the 1-year survival rate was 0.33 for patients who could ambulate preoperatively (Frankel D–E) compared with 0.26 for those who could not (Frankel A–C).

Neurological function

The neurological function postoperatively could be assessed in 278 of the 282 patients (Table 5). Among the 23 patients who had normal motor function preoperatively (Frankel E), all retained this function postoperatively. Twelve out of 255 patients with motor deficits were worsened postoperatively, whereas 179 improved at least one Frankel Grade. Among the 144 patients who were non-walkers but retained some motor function (Frankel C), 100 could walk at discharge (Frankel D–E). Even ten of 26 patients who had no motor function (Frankel A–B) regained sufficient neurological function to walk during follow-up.

Table 5.

Pre- and postoperative neurological function graded according to Frankel. Patients graded D or E have sufficient function to walk. Postoperative function not assessed in five patients due to early death

| Postoperative grade | Preoperative grade | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | Total | |

| A Complete paraplegia | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 9 (3%) |

| B No motor function | 0 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 9 (3%) |

| C Motor function useless | 2 | 9 | 36 | 3 | 0 | 50 (18%) |

| D Slight motor deficit | 1 | 4 | 87 | 18 | 0 | 110 (40%) |

| E No motor deficit | 0 | 0 | 12 | 64 | 23 | 99 (36%) |

| Total | 8 (3%) | 18 (7%) | 142 (51%) | 86 (31%) | 23 (8%) | 277 |

During the first 6 months postoperatively approximately 80% could walk, and this ability was retained at 1 and 2 years of follow-up (Table 6). Eleven patients are still alive 5 (2–10) years after surgery and ten of these are walkers.

Table 6.

Postoperative neurological function during follow-up

| Frankel grade | Follow-up after surgical treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months (%) | 6 months (%) | 1 year (%) | 2 years (%) | |

| A Complete paraplegia | 5 (3) | 4 (3) | 3 (4) | 2 (5) |

| B No motor function | 6 (3) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) |

| C Motor function useless | 23 (14) | 15 (12) | 5 (7) | 3 (7) |

| D Slight motor deficit | 44 (27) | 27 (22) | 15 (21) | 8 (19) |

| E No motor deficit | 88 (53) | 76 (61) | 47 (67) | 29 (67) |

| Number of patients alive | 166 | 125 | 71 | 43 |

Reoperations

A total of 29 patients were reoperated during follow-up, 17 at the same level and 12 at a new spinal level. The median time to reoperation for the 17 patients reoperated due to local progression of disease at the previously decompressed site and/or failure of the stabilization was 3 (0.4–9) years. Four of these patients were non-walkers (Frankel A–C) at the reoperation, all improved and became walkers and none were worsened by surgery. However, two patients eventually lost their walking ability during follow-up. The median survival after reoperation was 0.6 years and six out of 17 patients survived one year.

The 12 patients with epidural compression at a new spinal level were reoperated after only 0.7 (0.3–10) years. Seven of these were non-walkers and only one regained walking ability after the reoperation. Five were walkers and retained this function after the reoperation, but three of these later became paraplegic. The median survival was 0.3 years and only one of 12 patients survived 1 year.

Discussion

The indications for surgical treatment in spinal metastases at our institution appears quite different from many published series [15, 23]. Our most important surgical indication has been neurological deficit due to epidural compression. In our view, other modalities such as radiotherapy and advanced pain management will relieve pain in the vast majority of patients, and we have not considered pain as a sole indication for surgery. Furthermore, we consider all surgery for metastatic disease as palliative and will not significantly influence survival.

Only 8% of our patients had normal motor function compared with around 50% in many other series [15, 23]. In fact, two-thirds of our patients could not walk. Our series was dominated by prostate cancer (40%) and we had only a few patients with lymphomas or myelomas. Our patients were also older than in other series and most had extensive metastatic disease, with multiple skeletal metastases in 64% and non-skeletal metastases as well in 23%. These features lead to the poor survival reported here, with only 26% surviving 1 year, whereas others report 50–75% 1-year survival [15, 20, 23]. Interestingly, in a population-based study of surgery for spinal metastases from Canada the postoperative survival rate was similar to ours [6]. The most decisive proof that we have only operated patients with severe loss of function is the fact that the survival curve of patients operated on for spinal metastases is exactly the same as those operated in our department for pathological fracture of long bones [3].

Our series is comparable to non-operated patients with metastatic bone disease. In two large randomized studies of radiotherapy from The Netherlands and Great Britain, respectively, median age, distributions of primary tumors, and presence of non-skeletal metastases were similar to our series [4, 16]. Not surprisingly the 1-year survival was also similar to our series. We have not selected patients for surgery with an inherent good prognosis, and our series is thus more representative of cancer patients with extensive disease and a great need for palliative care. In the randomized studies cited, only 2 and 4% of the patients treated with radiotherapy subsequently developed symptoms of spinal cord compression. Therefore, spinal cord compression remains uncommon, and it is questionable whether there is an indication for surgical treatment to prevent epidural compression in patients with normal neurological function.

A major problem in selecting patients for surgery is to avoid operating on those that will die very soon after surgery. Even a pain-free survival of only a couple of weeks after surgery for pathological fracture of the hip is in our opinion good palliative care. We are not sure that this is the case for patients with severe neurological deficit due to spinal metastases. Although many patients improved considerably (at least one Frankel grade), a survival of at least 2 months will in most cases be necessary for the patient to have real benefit of the procedure, taking into account the postoperative pain, surgical complications and sometimes slow neurological recovery. We consider several features that help us to identify those with a good prospect for survival of more than 1 year [3, 19, 20], but we still have problems in identifying those that will die early. In this respect other clinical features well established in palliative care medicine, such as weight loss and low hemoglobin, may help us in excluding patients that are unlikely to live long enough to benefit from surgery for paraplegia [12].

The complication rate after palliative spinal surgery remains high [7, 13, 18, 23]. These cancer patients have several increased risk factors for local and systemic complications. Both their disease and treatment makes them immunodeficient, malnutrition and radiotherapy increases the risk of wound breakage and infection, and there is also increased risk of thromboembolic disease. We have not been able to reduce the wound infection rate despite reduced operating time, from a median of 3 h in 1990–1994 to 2 h in 1998–2001 (P<0.001).

In the first years of this series we operated on patients with significant neurological compromise as quickly as possible, often at night. We have changed this policy and now operate only in the daytime, within 24 h of admittance. We believe that daytime surgery with experienced staff and better perioperative resources leads to a lower rate of complications and better surgery. The possible risk of neurological deterioration during the waiting time at night, reduced by giving high-dose steroids, is outweighed by the benefits of daytime surgery.

Posterior decompression and stabilization has been our main surgical technique. Laminectomy only was reserved mostly for patients without pathological fracture and especially for those with epidural compression posteriorly from metastasis to the spinous process. We have not tried to attain bony fusion by using bone grafts. Our rationale is that radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy and the patients often catabolic status makes the likelihood for fusion small. We have also not prescribed external support postoperatively, as these are extremely difficult for the patients to withstand. Instead we have relied on the instrumentation to prevent further spinal collapse.

Anterior decompression and reconstruction of the vertebral body with bone cement was mostly applied during the last years of the study. We selected patients in good general health, with limited cancer disease and with only few spinal segments affected. With this selection both short- and long-term survival was better than for posterior procedures. We cannot draw any conclusions from this study whether there is a difference in outcome between anterior or posterior procedures as regards pain and neurological function.

Reoperations for recurrence of epidural compression at the previously operated level was only performed in 17 (6%) of the 282 patients. However, 14 of these reoperations occurred more than 1 year after the initial procedure and the risk of local failure for those surviving 1 year was 20%. In this group of patients, greater efforts to achieve local control of the metastatic growth may lead to lower reoperation rates. On the other hand, among those operated for epidural compression at a new level most occurred early after the first operation. The results both as regards survival and neurological restoration was poor probably due to the inherent aggressiveness of the tumors.

Patients who were non-walkers preoperatively had only slightly lower survival rates than walkers. If we had operated on more patients without neurological deficits, as in other series, there would probably have been a larger difference in survival. The most challenging clinical situation is the patient who is completely paraplegic at presentation. Generally, such patients were not operated on, irrespective of the duration of the paraplegia. However, Harrington has reported that even completely paraplegic patients can become walkers after anterior decompression and stabilization [9]. Hence, in singular cases surgical intervention may be indicated in even completely paraplegic patients. These are patients with limited disease, with a very good chance of surviving at least a year; for example, patients presenting with undiagnosed prostate cancer, myeloma or lymphoma. Ten out of 26 patients with complete paraplegia (Frankel A–B) became walkers, but the neurological restoration sometimes took several months. Furthermore, in patients with a good prognosis for long-term survival, the cost is small compared with the benefit of any neurological improvement that surgery can offer. For example, we had a 36-year-old patient who became suddenly paraplegic (Frankel A) when abroad, 5 days before he was admitted to our department. He had no history of cancer, and was operated with posterior decompression at Th 5 without instrumentation. Histology proved myeloma. He regained some motor function during the first weeks, and could walk with supports 4 months later. He is still alive 9 years later but has now neurologically deteriorated to Frankel C without epidural compression and can only stand for a couple of minutes.

There are several limitations with this study, mostly that it is a case series running over a long period of time, and we cannot completely account for patient selection. Ideally, we would like to randomize for radiotherapy or surgery, and also for the type of surgical intervention. If one chooses to operate on patients without neurological deficit one should randomize. Recently, a randomized study of surgery versus radiotherapy in cancer patients with neurological symptoms was closed prematurely because of the better results obtained with surgery [14]. Therefore, in our practice, where almost all patients have serious neurological deficits, randomization is impossible to justify. Instead we are now registering and follow not only operated patients but also those we decline surgery because of too little or too serious neurological symptoms or those who we believe have too extensive disease.

Conclusions

This study of 282 patients with spinal metastases shows that important improvement of function can be gained by surgical treatment. However, the complication rate was high and 27% of the patients died of their disease within 2 months of surgery. Comparing patients from the early and late periods, we have not improved our ability to identify those who will die early. Hence between 10 and 20% of the patients did not benefit from the surgical treatment, and some of these will in fact have been worsened due to complications and increased pain.

References

- 1.Aebi M. Spinal metastasis in the elderly. Eur Spine J. 2003;12(Suppl 2):S202–S213. doi: 10.1007/s00586-003-0609-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer HC. Posterior decompression and stabilization for spinal metastases: analysis of sixty-seven consecutive patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:514–522. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199704000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer HCF, Wedin R. Survival after surgery for spinal and extremity metastases: prognostication in 241 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995;66:143–146. doi: 10.3109/17453679508995508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bone Pain Trial Working Party 8 Gy single fraction radiotherapy for the treatment of metastatic skeletal pain: randomised comparison with a multifraction schedule over 12 months of patient follow-up. Radiother Oncol. 1999;52:111–121. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(99)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clayton D, Hills M. Statistical models in epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis LA, Warren SA, Reid DC, Oberle K, Saboe LA, Grace MAG. Incomplete neural deficits in thoracolumbar and lumbar spine fractures. Spine. 1993;18:257–263. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199302000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkelstein JA, Zaveri G, Wai E, Vidmar M, Kreder H, Chow E. A population-based study of surgery for spinal metastases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:1045–1050. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.85B7.14201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frankel HL, Hancock DO, Hyslop G, et al. The value of postural reduction in the initial management of closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia and tetraplegia. Paraplegia. 1969;7:179–192. doi: 10.1038/sc.1969.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrington KD. Anterior decompression and stabilization of the spine as treatment for vertebral collapse and spinal cord compression from metastatic malignancy. Clin Orthop. 1988;227:103–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CK, Rosa R, Fernand R. Surgical treatment of tumors of the spine. Spine. 1986;11:201–208. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198604000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loblaw AD, Laperriere NJ. Emergency treatment of malignant extradural spinal cord compression: An evidence-based guideline. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1613–1624. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obermair A, Handisurya A, Kaider A, Sevelda P, Kolbl H, Gitsch G. The relationship of pretreatment serum hemoglobin level to the survival of epithelial ovarian carcinoma patients: a prospective review. Cancer. 1998;83:726–731. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980815)83:4<726::AID-CNCR14>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pointillart, Ravaud A, Palussière J. Vertebral metastases. Berlin Heiddberg New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Regine WF, Tibbs PA, Young A, Payne R, Saris S, Kryscio RJ, et al. Metastatic spinal cord compression: a randomized trial of direct decompressive surgical resection plus radiotherapy vs. radiotherapy alone. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57(Suppl 2):125. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rompe JD, Hopf CG, Eysel P. Outcome after palliative posterior surgery for metastatic disease of the spine-evaluation of 106 consecutive patients after decompression and stabilization with the Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1999;119:394–400. doi: 10.1007/s004020050008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steenland E, Leer J, Houwelingen H, Post WJ, Hout WB, Kievit, et al. The effect of a single fraction compared to multiple fractions on painful bone metastases: a global analyses of the Dutch Bone Metastasis Study. Radiotherapy Oncol. 1999;52:101–109. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(99)00110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundaresan N, Rothman A, Manhart K, Kelliher Surgery for solitary metastases of the spine: rationale and results of treatment. Spine. 2002;27:1802–1806. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200208150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sundaresan N, Sachdev VP, Holland JF, Moore F, Sung M, Paciucci PA, et al. Surgical treatment of spinal cord compression from epidural metastasis. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2330–2335. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.9.2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tokuhashi Y, Matsuzaki H, Toriyama S, Kawano H, Ohssaka S. Scoring system for preoperative evaluation or metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine. 1990;15:1110–1113. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199011010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomita K, Kawahara N, Kobayashi T, Yoshida A, Murakami H, Akamaru T. Surgical strategy for spinal metastases. Spine. 2001;26:298–306. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200102010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wedin R, Bauer HFC, Skoog L, Söderlund V, Tani E. Cytological diagnosis of skeletal lesions. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy in 110 tumours. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:673–678. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.82B5.9992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wenger M. Vertebroplasty for metastasis. Med Oncol. 2003;20:203–209. doi: 10.1385/MO:20:3:203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wise JJ, Fishgrund JS, Herkowitz HN, Montgomery D, Kurz LT. Complication, survival rates, and risk factors of surgery for metastatic disease of the spine. Spine. 1999;24:1943–1951. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199909150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]