Abstract

Spinal angiolipomas are extremely rare benign tumors composed of mature lipomatous and angiomatous elements. Most are symptomatic due to progressive spinal cord or root compression. This article describes the case of a 60-year-old woman who presented with a 6-month history of low back pain radiating to her right leg. The pain was multisegmental. The condition had worsened with time. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging revealed a dorsal epidural mass at L5 and erosion of the lamina of the L5 vertebra. Laminectomy was performed, and an extradural tumor was totally excised. Neuropathologic examination identified it as a lumbar spinal angiolipoma. There was no evidence of recurrence in follow-up 12 months later. This rare clinical entity must be considered in the differential diagnosis for any spinal epidural lesion.

Keywords: Angiolipoma, Spinal tumor

Introduction

Spinal angiolipomas are very unusual benign extradural neoplasms. It is reported that these lesions account for 0.04–1.2% of all spinal axis tumors and 2–3% of all extradural spinal tumors [1, 16]. Most spinal angiolipomas arise in the thoracic epidural space; lumbar occurrence is extremely rare [9]. Lumbar spinal angiolipoma was first reported by Kasper and Cowan [3] in 1929. Since then, only 12 such cases have been documented [2, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 15]. In this paper, we present another case of lumbar spinal angiolipoma and discuss the relevant literature.

Case report

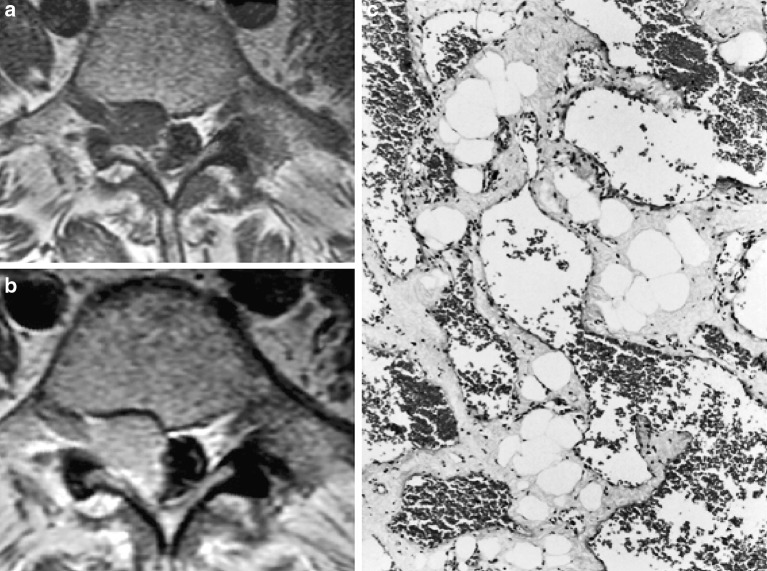

A 60-year-old woman presented to our outpatient clinic with a 6-month history of low back pain radiating to her right leg. The pain reflected from right below the kneecap to the base of the right foot. Apart from this pain, all physical examination findings on admission were normal. The only abnormality on neurological examination was a hypoactive right Achilles. The results of routine laboratory tests were unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an extradural mass and erosion of the lamina of the L5 vertebra. The mass was hypointense to neural tissue on T1-weighted images (Fig. 1a) and hyperintense on T2-weighted images, it also showed marked enhancement after contrast administration (Fig. 1b). Surgery was performed, and L5 laminectomy revealed a highly vascularized extradural tumor. The mass was totally excised. When the patient awoke from surgery, she was no longer in pain. Histopathological examination of the surgical specimen showed a neoplasm composed of mature adipose tissue and blood vessels (Fig. 1c). The diagnosis was spinal angiolipoma. The patient was discharged on the fourth day postoperative with no pain and no other neurologic deficits. There was no evidence of recurrence in follow-up 12 months later.

Fig. 1.

a (left upper): A T1-weighted axial magnetic resonance image shows the hypointense epidural mass. b (left lower): An axial magnetic resonance image after contrast injection shows marked enhancement of the lesion. c (right): The lesion contained a mix of mature adipocytes and large, branching, blood-filled cavernous vascular channels (H&E, ×100)

Discussion

Spinal angiolipomas are categorized as one of two types: “non-infiltrating” and “infiltrating.” The majority of these tumors are non-infiltrating and do not involve the vertebra or other surrounding tissues [3, 5, 8, 10, 14, 16]. This form is most often seen in young adults, and multiple tumors are common. The “infiltrating” type of spinal angiolipoma is encapsulated and contains areas with a dominant vascular component [12]. The infiltrating form tends to arise in ventral locations within the thoracic and lumbar portion of the spinal column, and these lesions typically invade vertebral bodies and pedicles [2, 7, 13, 15].

Angiolipomas are benign mesenchymal neoplasms composed of mature adipose tissue and abnormal blood vessels. The vessel caliber ranges from capillary size to arterial size. These lesions are considered a subgroup of lipomas [2–4, 14]. Spinal angiolipomas differ from spinal lipomas in several ways. The former usually appear in adults, are almost always located in the epidural space, and are not associated with congenital myelovertebral malformations. In contrast, the latter typically arise in childhood and are usually located in epi- and intradural spaces; most are associated with congenital myelovertebral malformations. There is no consensus on the pathogenesis of spinal angiolipoma [6, 9, 12, 14, 16].

We conducted a detailed review on the literature of the 12 previous cases of lumbar spinal angiolipoma that have been reported (Table 1) [2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 15]. Seven (58%) of these patients were female and five (42%) were male, and the age range was 6–85 years (median, 44 years). This tumor type/location appears to be uncorrelated with age or sex. Nine (75%) of the affected patients had non-infiltrating lumbar angiolipomas and three (25%) had the infiltrating form. These 12 cases indicate that the non-infiltrating form of spinal angiolipoma is much more common than the infiltrating type. Our patient also had a non-infiltrating lumbar angiolipoma.

Table 1.

Summary of the non-infiltrating and infiltrating lumbar spinal angiolipomas that have been reported to date and current case

| References | Sex/Age (years) | Site | Duration of symptoms | Treatment | Result | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kasper and Cowan [3] | M/6 | L3–S2 | 4 days | No Surgery | Necsropsy | Non-infiltrating |

| Gonzales-Crussi et al. [2] | F/21 | L3 body + lamina | 3 years | Surgery and RT | Recovery | Infiltrating |

| Lo Re and Michelacci [5] | M/16 | Caudal | Unknown | Surgery | Recovery | Non-infiltrating |

| Lo Re and Michelacci [5] | F/35 | Lumbar | Unknown | Surgery | Recovery | Non-infiltrating |

| Scanarini and Carteri [14] | M/46 | Lumbar | Unknown | Surgery | Recovery | Non-infiltrating |

| Schiffer et al. [15] | F/48 | L1 body | 3 years | Surgery | Recovery | Infiltrating |

| Pagni and Canavero [7] | F/56 | L3 body + Pedicle | 12 years | Surgery | Recovery | Infiltrating |

| Pagni and Canavero [7] | F/59 | L4–L5 | 27 years | Surgery | Unknown | Non-infiltrating |

| Provenzale and McLendon [10] | F/38 | Lumbar | 3 years | Surgery | Unknown | Non-infiltrating |

| Pinto-Rafael et al. [8] | M/85 | L1–L2 | 1 day | Surgery | Recovery | Non-infiltrating |

| Rocchi et al. [12] | M/60 | L3–L4 | 2 years | Surgery | Recovery | Non-infiltrating |

| Rocchi et al. [12] | F/54 | L3 | 1 year | Surgery | Recovery | Non-infiltrating |

| Current case | F/60 | L5 | 6 months | Surgery | Recovery | Non-infiltrating |

Clinically, most individuals with spinal angiolipoma present with symptoms related to spinal cord and root compression. Sudden onset or worsening of neurological symptoms occurs when there is a rapid increase in tumor size due to intratumoral thrombosis, hemorrhage, or a steal phenomenon [6, 8]. Our patient exhibited symptoms of a root compression syndrome.

On computed tomography without contrast, spinal angiolipomas typically appear hypodense and can be misdiagnosed as epidural fat tissue. However, some of these lesions appear isodense, likely to be related to the extent of vascularity [1]. Magnetic resonance imaging is the most valuable radiological modality for diagnosing spinal angiolipomas. These tumors are typically hyperintense on non-contrast T1-weighted images owing to their fatty content [1, 10, 16]. Provenzela and McLendon [10] showed that large hypointense foci observed within spinal angiolipomas on non-contrast T1-weighted images are correlated with increased vascularity. Our patient’s lesion appeared hypointense on non-contrast T1-weighted images, and the surgical specimen was indeed vascular (Fig. 1). Angiography is another radiological modality that is used to diagnose and treat spinal angiolipomas. When hypointense foci are detected on non-contrast T1-weighted images, angiography can be done to investigate further and embolization can be performed. Embolization of a highly vascularized angiolipoma can facilitate surgical removal.

Gonzalez–Crussi et al. [2] treated their one case of lumbar angiolipoma with surgery and radiotherapy. However, neither adjuvant chemotherapy nor radiotherapy is recommended for these benign lesions, even when incomplete removal only is achieved. The treatment of choice for this neoplasm is surgery alone. Most non-infiltrating spinal angiolipomas are located in the dorsal portion of the epidural space, and can thus be removed via posterior laminectomy. In contrast, the reported infiltrative cases suggest that this tumor type tends to be located ventrally or ventrolaterally in the spinal canal. Such lesions have required anterior and anterolateral decompressive surgery as opposed to posterior laminectomy [7, 11, 16].

In conclusion, complete surgical excision is believed to be curative in most cases of lumbar spinal angiolipoma; no further treatment is needed. If magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography findings suggest a highly vascular tumor, angiography, and embolization can be performed before surgery to facilitate the operation.

References

- 1.Fourney DR, Tong KA, Macaulay RJ, Griebel RW. Spinal angiolipoma. Can J Neurol Sci. 2001;28:82–88. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100052628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez-Crussi F, Enneking WF, Arean VM. Infiltrating angiolipoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1966;48:1111–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasper JA, Cowan A. Extradural lipoma of the spinal canal. Arch Pathol. 1929;8:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin JJ, Lin F. Two entities in angiolipoma: a study of 459 cases of lipoma with review of literature on infiltrating angiolipoma. Cancer. 1974;34:720–727. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197409)34:3<720::aid-cncr2820340331>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo Re F, Michelacci M. Clinical and surgical findings on various lumbo-sacral abnormalities associated with angiolipoma. Arch Putti Chir Organi Mov. 1969;24:70–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oge HK, Soylemezoglu F, Rousan N, Ozcan OE. Spinal angiolipoma: case report and review of literature. J Spinal Disord. 1999;12:353–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pagni CA, Canavero S. Spinal epidural angiolipoma: rare or unreported? Neurosurgery. 1992;31:758–764. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199210000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinto-Rafael JI, Vazquez-Barquero A, Martin-Laez R, Garcia-Valtuille R, Sanz-Alonso F, Figols-Guevara FJ, et al. Spinal angiolipoma: case report. Neurocirugia. 2002;13:321–325. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1473(02)70609-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preul MC, Leblanc R, Tampieri D, Robitaille Y, Pokrupa R. Spinal angiolipomas: report of three cases. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:280–286. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.2.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Provenzale JM, McLendon RE. Spinal angiolipomas: MR features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:713–719. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabin D, Hon BA, Pelz DM, Ang LC, Lee DH, Duggal N. Infiltrating spinal angiolipoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004;17:456–461. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000109834.59382.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rocchi G, Caroli E, Frati A, Cimatti M, Savlati M. Lumbar spinal angiolipomas: report of two cases and review of the literature. Spinal Cord. 2004;42:313–316. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakaida H, Waga S, Kojima T, Kubo Y, Matsubara T, Yamamoto J. Thoracic spinal angiomyolipoma with extracanal extension to the thoracic cavity: a case report. Spine. 1998;23:391–394. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199802010-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scanarini M, Carteri A. Intrarachidian lipomas: observations on 4 cases and pathogenetic considerations. J Neurosurg Sci. 1974;18:136–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiffer J, Gilboa Y, Ariazoroff A. Epidural angiolipoma producing compression of the cauda equina. Neurochirurgia. 1980;23:117–120. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1053871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turgut M. Spinal angiolipomas: report of a case and review of the cases published since the discovery of the tumor in 1890. Br J Neurosurg. 1999;13:30–40. doi: 10.1080/02688699944159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]