Abstract

The surgical management of thoracolumbar fractures presents potential benefits. However, the surgery solve the instability by fusion of mobile segments. We incorporate in our treatment algorithms, the use of restricted arthrodesis at injured levels, regardless of longer instrumentations, as well as the use of non-fused transitory stabilizations, based on the conviction that in non-fused segments without traumatic disc injury, mobility persists once the instrumentation is removed. The goals of this study were to compare the mobility of non-fused segments after hardware removal to a normal range of motion and to find prognostic pre-op imaging patterns. We reviewed 21 consecutive patients who underwent surgery with preservation of mobile segments (non-fused segments included in the construction) in order to recover mobility after removal of instrumentation, performed between 1995 and 2001. All patients were treated by indirect reduction with posterior transpedicular instrumentation. Clinical and radiological outcome was analyzed after an average follow-up of 46.6 months. Satisfactory subjective outcome results were obtained in 94.7%. The dynamic radiological follow-up study showed 75% (21 segments) with normal or decreased range of motion (ROM) and 25% (7 segments) without mobility. The non-fused segments with hardware removal before 10 months of evolution presented a normal or decreased mobility in 83.2% while the segments with hardware removal after 10 months showed 68.8% of mobility. The intervertebral disc (IVD)’s with normal initial MRI morphology preserved their mobility in 81.9%. Complications occurred in four patients: two superficial wound infections and two patients presented a late fracture of one USS Schanz. The results of this study prove that in thoracolumbar fractures, non-fused spinal segments included in pedicular instrumentation maintained mobility in a high percentage once the hardware is removed. 75% of the segments presented a normal or decreased ROM.

Keywords: Intersegmental spinal mobility, Short segment fixation, Spinal fusion, Thoracolumbar spinal fractures, Transpedicular instrumentation

Introduction

The management of thoracolumbar fractures (TLF) has experienced rapid development during the last years. The progress in imaging and the development of new stabilization systems has allowed a better understanding of injury mechanism, the degree of instability associated and has led to the creation of therapeutic algorithms [21, 22, 29, 32–34, 37, 43, 52, 53, 56].

Surgical management presents potential benefits including neural decompression, spinal anatomy restoration and inmediate stability, which improves the integral rehabilitation of patients and allows them a rapid return to work [1, 19, 27, 32, 34, 37, 38, 43, 47, 49, 52, 53]. Historically, most surgical techniques solved the problem of instability by fusion of mobile segments. This clearly restricts one of the basic functions of the spine: movement. Therefore, fusion generates controversy regarding immediate benefits and late consequences [5, 14, 30, 48]. Negative effects in spine fusion have been reported, including pseudoarthosis, spinal stenosis, spondylolysis and accelerated degeneration of non-fused segments [5, 28, 39, 44, 48]. The main argument to fuse in thoracolumbar spine fractures is the lack of correction noticed in surgeries without arthrodesis, which is mainly caused by the degeneration of intervertebral discs involved in the fracture [3, 9, 27, 30, 31, 37, 38, 43], or by the presence of capsuloligamentous disruptive injuries of the posterior column [34, 40, 55].

The evolution of reconstructive surgery has incorporated an important concept: to restrict the number of fusion segments. In 1980, Jacobs et al. [25] presented the concept of “Rod long, fuse short” for the surgical treatment of TLF with Harrington instrumentation: three segments above and three segments below the fracture were stabilized while fusion was limited, to an average of 1.4 segments. They reported a high percentage of segments with mobility and without facetary degenerative changes once the instrumentation was removed. Later, the introduction of pedicular instrumentation allowed to reduce fixation levels (short fixations) and preserve mobility of unaffected segments [5, 11, 30, 31, 32, 34, 37, 38, 52, 53]. In 1993, Lindsey and Dick [31] reported the presence of residual mobility after removal of pedicular instrumentation, observing that the segments with end plate or intervertebral disc (IVD) disruption go to ankylosis. They suggested that in those fractures affecting only the upper vertebral plate, fusion should be restricted to those segments.

There is still controversy and few studies available on clinical and imaging evolution, and on residual mobility of non-fused vertebral segments, which are temporarily included in instrumentations of TLF [5, 30, 34, 38, 46]. Recent reports observed the presence of healthy IVDs in non-fused segments once the instrumentation was removed [18, 41, 42, 45].

The experience we have gained with pedicular fixation, has led us use treatment algorithms with restricted arthrodesis at injured levels, regardless of longer instrumentations, as well as non-fused transitory stabilizations in those fractures where the stability of the segment is recovered once the fracture is consolidated (B2 AO or Chance type) [34, 37, 52]. This is based on the conviction that in non-fused segments without traumatic disc injury, the mobility persists once instrumentation is removed. It is very important to keep in mind that our affected population is generally young and the preservation of mobile segments, mainly at a lumbar level, will be beneficial for them in the future.

Objectives

To confirm mobility in non-fused and temporarily stabilized vertebral segments in the surgical management of TLF. To compare the degree of this mobility in relation to a normal range of motion (ROM).

To determine the presence of eventual pre-surgical imaging patterns that allow prognostic/factors of spinal segments or IVD involved in the fractures.

Material and methods

Medical files of 138 patients with TLF, operated between January 1995 and May 2001 were studied. Twenty-one cases met the criteria of inclusion: fractures of the thoracolumbar hinge (T11-L1) and/or lumbar spine without or partial neurological damage that were handled with a USS internal fixator and hardware removal at the time of evaluation. Patients with fractures in the upper and medium thoracic spine pathological fractures and those with full neurological damage were excluded from this study.

Fractures were classified according to the AO classifications of TLF [21, 33]. According to our criteria, we consider subsidiary of using the technique with preservation of mobile segments:

A, B1 and C AO fractures with surgery indication, with only one injured spinal segment, whether the IVD and/or the posterior ligament complex, in which the pathomorphological characteristics of the injury make a fixation and a monosegmentary fusion unsuitable. In these cases we practice a bisegmentary stabilization and a monosegmentary fusion.

TLF that are concomitant in more than one segment and adjacent, which require long stabilizations and only fusion of the levels with discal injury and/or injuries of the posterior ligament complex, we call long instrumentation-short fusion.

B2 AO type fractures, also known as Chance type fractures, which have absolute no surgical indication. However, the conservative treatment implies the use of prolonged external immobilization and, consequently, a period of rehabilitation which, for current times, we consider it be the best treatment for a working young population. For these patients, our protocol is to perform non-fused, transitory and bisegmentary stabilization.

From 29 reviewed cases, 8 of them were excluded because at the time of the evaluation, the instrumentation was not removed. 21 patients met the inclusion criteria and were requested to undergo a new clinical and imagenological evaluation for follow-up. Out of these 21 cases, 19 were evaluated (90.5%). 18 men and 1 woman, age average of 33.1 years (±11.3 SD, range 19–59) at the time of the fracture. The fractures were caused by fall from height in 12 cases (63.1%), car accidents in 6 cases (31.6%) and direct impact in 1 case (5.3%), Associated injuries were present in 13 patients (68.4%). Pre-operatively, all patients underwent conventional radiolographic and computerized topographic. In addition 84% (16 patients) had magnetic resonance (MRI).

According to the AO classification fractures were divided as A2 = 2 cases, A3 = 5 cases, B1 = 5 cases, B2 = 6 cases and C1 = 1 case. 84.6% corresponded to Frankel E (16 cases), 2 cases to Frankel D (10.26%) and one patient to Frankel C (5.13%) [37, 38]. Injured levels were: T12 (n=5, 20.8%), L1 (n=10, 41.7%), L2 (n=6. 25%), and L3 (n=3, 12.5%). Instrumented and fused spinal segments are described in table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of evaluated cases in follow-up

| Case | Age/sex | Frankel adm. | Diagnosis | Instr. L | Fus. L | Non fus. L | LBOS | Frankel foll. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 35/m | E | A3 L1/A1 L2 | T12-L2 | T12-L1 | L1-L2 (1) | 71/ E | E |

| 2 | 28/f | E | B2 T12 | T11-L1 | N | T11-L1 (2) | 70/E | E |

| 3 | 20/m | E | B2 L1/ A1 L2 | T12-L2 | N | T12-L2 (2) | 48/R | E |

| 4 | 25/m | E | B2 L1 | T12-L2 | N | T12-L2 (2) | 20/P | E |

| 5 | 27/m | E | B1T11-T12 | T11-L1 | T11-T12 | T12-L1 (1) | 71/E | E |

| 6 | 31/m | E | B1 T12-L1/ A3 L3 | T12-L3 | T12-L2 | L2-L3 (1) | 74/E | E |

| 7 | 35/m | E | A3 L1 | T12-L2 | T12-L1 | L1-L2 (1) | 75/E | E |

| 8 | 22/m | E | B2 L1 | T12-L2 | N | T12-L2 (2) | 71/E | E |

| 9 | 44/m | E | A2 L2 | L1-L3 | N | L1-L3 (2) | 75/E | E |

| 10 | 21/m | E | A3 L2 | L1-L3 | N | L1-L3 (2) | 70/E | E |

| 11 | 26/m | D | B2 T12/ A1L2 | T11-L1 | N | T12-L2 (2) | 69/E | E |

| 12 | 59/m | D | B1 T12-L1 | T12-L2 | T12-L1 | L1-L2 (1) | 67/E | E |

| 13 | 39/m | C | A3 L1/A1 L3 | T12-L4 | L2-L4 | T12-L2 (2) | 55/B | D |

| 14 | 48/m | E | C1 T11-T12 | T11-L1 | T11-T12 | T12-L1 (1) | 63/B | E |

| 15 | 49/m | E | A3 L1 | T12-L2 | T12-L1 | L1-L2 (1) | 70/E | E |

| 16 | 41/m | E | A3 L2 | L1-L3 | L1-L2 | L2-L3 (1) | 75/E | E |

| 17 | 19/m | E | B2 T12 | T11-L1 | N | T11-L1 (2) | 55/B | E |

| 18 | 23/m | E | B1 L2-L3 | L2-L4 | L2-L3 | L3-L4 (1) | 64/B | E |

| 19 | 28/m | E | A2 L1 | T12-L2 | L1-L2 | T12-L1 (1) | 60/B | E |

instr L Instrumented levels, Fus. L Fused levels, Non fus L Non fused levels

Frank Frankel admisión and follow up

LBOS Low back outcome score. Excellent, good, fair and poor.

Management

Patients were operated by a posterior approach, using a standard surgical technique, which is ventral decubitus over four pillars under general anesthesia. Pedicular instrumentation was performed with USS internal fixator (Synthes) under image instensifier guidance. Fracture reduction was obtained by indirect manipulation with pedicular Schanz (ligamentotaxis and angular reduction) of the instrumented segments. Careful dissection was carried out, preserving the articular anatomy in those non-fused segments. In some cases, transmuscular instrumentation was performed under image intensifier control in order not to injure healthy segments. In fused spinal segment, posterolateral arthrodesis beds were prepared, respecting those levels not fused, and autologous bone graft taken from the posterior iliac crest was added.

In only one patient, an external support was used (Jewett brace). Every patient was kept in a periodical ambulatory clinical and radiological follow-up, under a permanent rehabilitation program.

Ostheosynthesis material was removed in an average time of 325.6 days (±69.5 SD, range 184–445).

Evaluations

Patients were called for a physical exam, plus a clinical and radiological evaluation of the affected segment, including a dynamic study of the spine in flexion and extension.

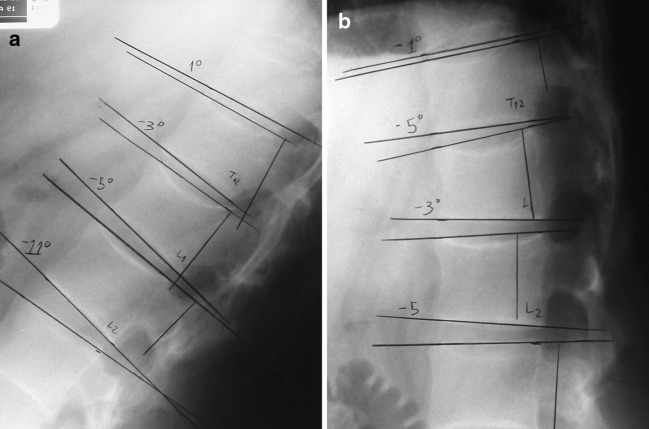

Radiological measurements

Monosegmentary discal height: defined as the discal height average of the anterior and posterior edge of each segment (IVD) in every instrumented level (fused or non-fused) and adjacent levels to the instrumentation [38].

Spinal mobility levels: the technique described by Tanz [38, 50] was used to evaluate the residual mobility of the non-fused, fused and adjacent spinal segments by means of lateral dynamic radiographyes in maximum voluntary flexion and extension.

Radiographic measurements were carried out before and after surgery, prior to the removal of instrumentation, and at the moment of late follow-up, with the exception of intervertebral mobility, which was measured only in late follow-up (Figs. 1–7).

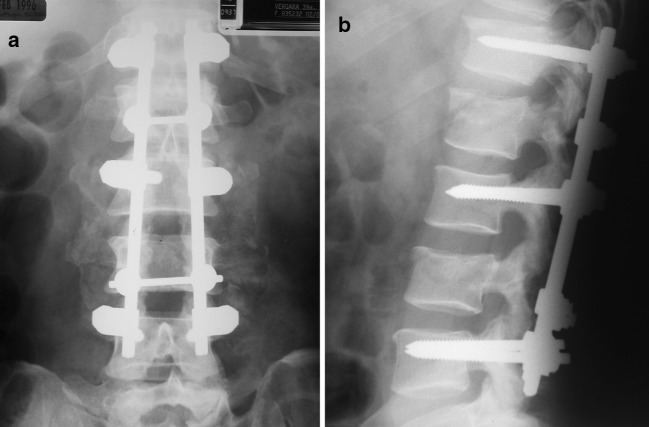

Fig. 2.

a AP and b lateral post-operative radiographs

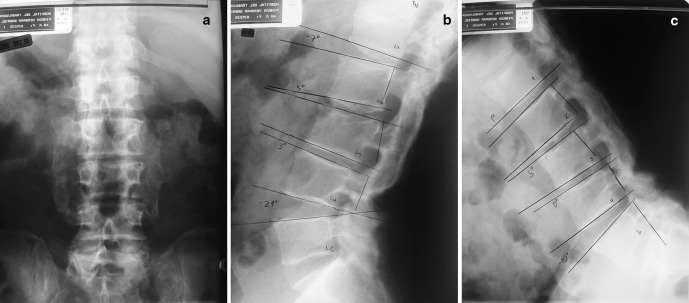

Fig. 3.

a AP, b extension and c flexion radiographs (73 months)

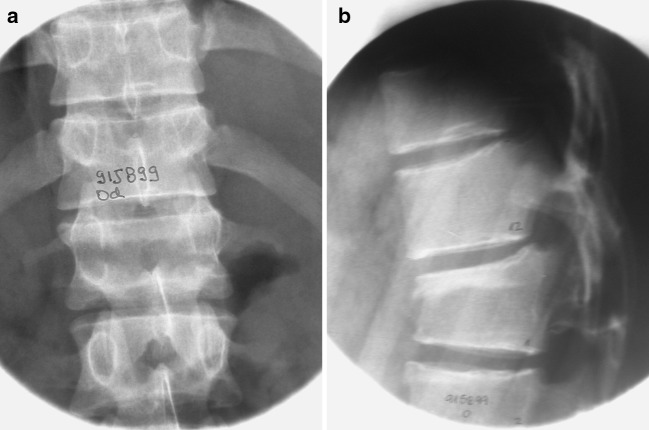

Fig. 4.

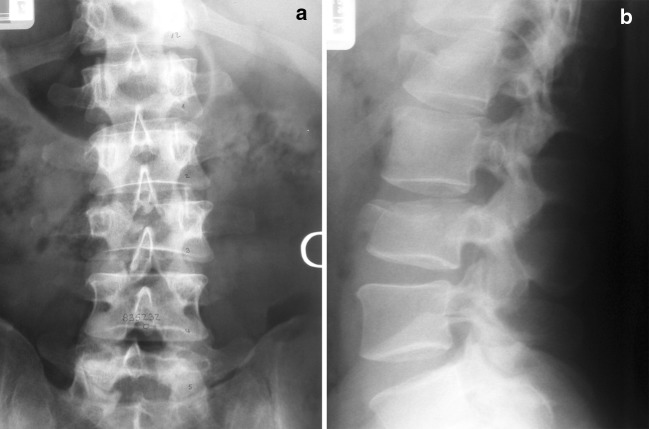

a Anteroposterior (AP) and b lateral radiographs B2 L1 fractures

Fig. 5.

Sagittal T2 MRI

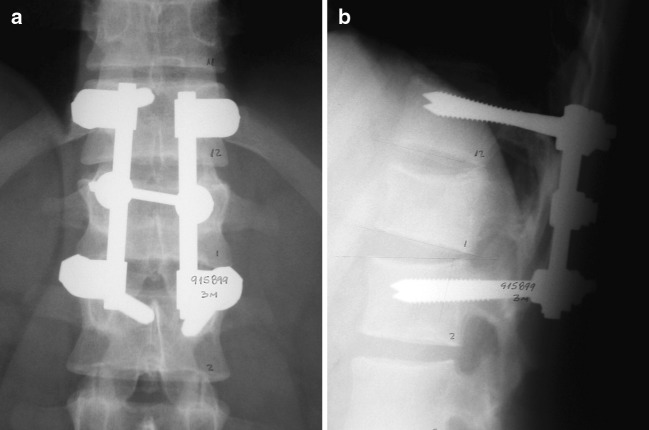

Fig. 6.

a AP and b lateral radiographs (3 months)

Fig. 1.

a Anteroposterior (AP) and b lateral radiographs A1 L1 and A3 L3 fracture

Fig. 7.

a Extension and b flexion lateral radiographs (66 months)

Residual mobility in the evaluated segments was compared to the normal ROM established by Dvorak et al. [13] (table 2). Mobility ranges are subdivided in:

Normal: values within normal ROM for each segment.

Decreased: mobility below normal ROM and above 20% of the average normal mobility for each segment.

Non-mobile: mobility below 20% of the average normal mobility for each segment.

Table 2.

Normal range of motion (ROM, in degrees), with standard deviation values (SD) in spinal segments (Dvorak et al. [13])

| Segmento | ROM | SD |

|---|---|---|

| T10-T11 | 5.0 | 2* |

| T11-T12 | 5.0 | 2* |

| T12-L1 | 8.0* | 2.2* |

| L1-L2 | 11.9 | 2.27 |

| L2-L3 | 14.5 | 2.29 |

| L3-L4 | 15.3 | 2.04 |

| L4-L5 | 8.2 | 2.99 |

* Presumed values.

Magnetic resonance evaluation

Retrospectively, the IVD’s adjacent to the fractured vertebral body (superior and inferior) were evaluated in the pre-operative MRI in T1 and T2 sagittal standardized sequences for thoracolumbar trauma. Special interest was put on those segments which were not fused.

According to the modified classification of Von Gumppenberg [18, 54] the morphological changes of the IVD’s were divided into three categories: Category 1 means no difference between the disc adjacent to the vertebral fracture and a comparable non-injured. Category 2 discs had assumed a more ellipsoid form or had small bulges into the vertebral plate. Category 3 discs were infracted into the vertebral body or herniated into the endplate.

MRI signal intensity was analyzed according to T2-weighted signal variation. Notice that this shows the level of hydrogen (mainly H2O) and its decrease might be associated with previous disc degeneration. Discs adjacent to the fracture were compared to non-injured discs below, generally L3–L4. Three categories were used: increased, normal and decreased T2-weighted signal intensity [7, 18, 51]. The data obtained should be considered as a subjective assessment, as it was not possible to quantify the signal intensity.

Clinical evaluation

The clinical evaluation consisted of a complete physical exam and the application of the Low Back Outcome Score (LBOS) questionnaire, designed by Greenough and Fraser [23]. This evaluation system consist of 13 parameters, including pain, work status, sport activities, necessary resting time and dayliving activities. The results were divided into: excellent (65–75), good (50–64), regular (30–49) and poor (0–29).

Statistical analysis

The data obtained was statistically analyzed using SPSS/PC 11.0. The ROM of the analyzed segments was compared with the ranges of normal motion. Further, the results of the LBOS were correlated with the radiological results using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

Results

The average follow-up time of the 19 evaluated cases was 46.6 months (±24.3 SD, range 6–74). According to LBOS, satisfactory results were obtained in 18 patients (94.7%) and poor results were obtained in only 1 patient (table 3).

Table 3.

Low back outcome score results

| Result | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Excellent | 12 | 63.1 |

| Good | 5 | 26.3 |

| Regular | 1 | 5.3 |

| Poor | 1 | 5.3 |

In instrumented segments (transitorily non-fused stabilized segments), an average loss of 24% (±14.7 SD) of discal height was found. In instrumented fused segments, the average of discal height loss was 56% (±18.7 SD). Instrumented segments had an average of 4.8° residual mobility (±3.26° SD) and instrumented fused levels, an average of 0.5° (±0.6° SD) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Average values (± SD) of discal height evolution and ROM: superior and inferior level to instrumentation, fused level and non-fused level

| - | Discal Height | ROM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-sur | Pre-rem | Follow up | ||

| Superior level | 100% | 93% (6.5) | 84% (9.9) | 3.84° (2.8) |

| Fused level | 100% | 87% (11.4) | 44% (18.7) | 0.5° (0.6) |

| Non-fused level | 100% | 92% (8.9) | 76% (14.7) | 4.8° (3.3) |

| Inferior level | 100% | 95% (7.9) | 91% (9.4) | 7.8° (4.1) |

28 instrumented segments were transitorily stabilized in 19 patients. 16 segments (8 cases) corresponded to transitory non-fused bisegmentary stabilizations (6 B2 fractures, 1 A2 fracture and 1 A3 fracture). The dynamic radiological follow-up study showed that 27 segments had some degree of mobility and only one level was considered as ankylosed (0°). According to the established definition, 21 segments (75%) presented normal or decreased ROM and 7 segments (25%) were considered as non-mobile (Tables 5, 6). Case 19 corresponds to a patient who haden ankylosis of the non-fused segment included in stabilization, and presented an A2 fractures of L1 fracture that involved both vertebral plates, an arthrodesis was performed in the inferior level of the fracture.

Table 5.

ROM degrees and mobility classification of the 28 transitorily and instrumented non-fused segments

| Level | Mobility | Classif. Mob. |

|---|---|---|

| L1-L2 | 6° | decrease |

| T11-T12 | 1° | decrease |

| T12-L1 | 5° | decrease |

| T12-L1 | 2° | decrease |

| L1-L2 | 2° | NM |

| T12-L1 | 5° | decrease |

| L1-L2 | 7° | decrease |

| T12-L1 | 2° | decrease |

| L2-L3 | 2° | NM |

| L1-L2 | 1° | NM |

| T12-L1 | 7° | N |

| L1-L2 | 6° | decrease |

| L1-L2 | 11° | N |

| L2-L3 | 11° | decrease |

| L1-L2 | 5° | decrease |

| L2-L3 | 2° | NM |

| T11-T12 | 3° | N |

| T12-L1 | 7° | N |

| L1-L2 | 1° | NM |

| T12-L1 | 4° | decrease |

| L1-L2 | 6° | decrease |

| T12-L1 | 4° | decrease |

| L1-L2 | 1° | NM |

| L2-L3 | 6° | Decrease |

| T11-T12 | 4° | N |

| T12-L1 | 6° | N |

| L3-L4 | 13° | N |

| T12-L1 | 0° | NM |

Table 6.

ROM summary non-fused segments

| N° | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 7 | 25 |

| Decreased | 14 | 50 |

| Non-mobile | 7 | 25 |

ROM’s of instrumented segments can be separated into two groups. (table 7) Group 1: 16 levels with transitory and non-fused bisegmentary stabilizations, in which 87.5% of mobile levels were found with an average discal height of 81.2%. Group 2: 12 non-fused levels, included in long instrumentations with short arthrodesis, in which a 58.4% of mobile levels were found with an average discal height of 63.8%.

Table 7.

ROM according to surgical technique. Group 1: non-fused bisegmentary instrumentation. Group 2: long instrumentation-short fused

| N° | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | ||

| Normal | 6 | 37.5 |

| Decreased | 8 | 50 |

| Non-mobile | 2 | 12.5 |

| Group 2 | ||

| Normal | 1 | 8.4 |

| Decreased | 6 | 50 |

| Non-mobile | 5 | 41.6 |

The instrumented segments, in which the ostheosynthesis material was removed before 10 months of evolution, presented a normal (41.6%) or decreased (41.6%) mobility in an 83.2%. However, the segments which were instrumented for more than 10 months were considered to have 68.8% mobility (Table 8).

Table 8.

ROM according to instrumentation removal time

| N° | % | |

|---|---|---|

| <10 months | ||

| ,Normal | 5 | 41.6 |

| Decreased | 5 | 41.6 |

| Non-mobile | 2 | 16.8 |

| >10 months | ||

| Normal | 2 | 12.5 |

| Decreased | 9 | 56.3 |

| Non-mobile | 5 | 31.2 |

In 19 instrumented segments, a correlation between morphology and intensity of signal in pre surgical MRI was made with respect to its residual mobility. (Table 9).

Table 9.

ROM summary according to morphology and signal intensity of IVD’s involved in pre-surgical MRI

| Normal | Decreased | Non-mobile | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discal morphology | |||

| Type 1 | 27.3% (3) | 54.6% (6) | 18.1% (2) |

| Type 2 | 42.9% (3) | 14.2 (1) | 42.9% (3) |

| Type 3 | 100% (1) | ||

| Signal intensity | |||

| Increased | 30% (3) | 50% (5) | 20% (2) |

| Normal | 37.5% (3) | 37.5% (3) | 25% (2) |

| Decreased | 100% (1) | ||

Discal morphology: Type 1 (11 IVD, 58% of all investigated discs): 81.9% presented mobility (3 normal and 6 decreased). 18.1% were considered as non-mobile (2 segments). Type 2 (7 IVD): 57.1% presented mobility (3 normal and 1 decreased). 42.9% were considered as non-mobile (3 segments). Type 3 (1 IVD): there was only one IVD with this morphology in the evaluated segments, which had decreased mobility.

Signal intensity: Increased (10 IVD): 80% IVD were mobile (3 normal and 5 decreased). 20% were considered as non-mobile (2 cases). Normal (8 IVD): 75% mobile segments (3 normal and 5 decreased). 25% (2 segments) were non-mobile. Decreased (1 IVD): only one IVD presented these characteristics and in the evaluation, the segment was non-mobile.

No statistical significance in the correlation of ROM versus LBOS was observed. No statistical correlation was found between ROM and morphologic characteristics and intensity of evaluated segments since the sample was too small.

The average time out of work was 129.2 days (±51.6 SD, range 45–230) in the first surgery. In all 8 patients with non-fused transitory stabilizations, the time out of work was 104.5 days (±32.7 SD, range 45–165), and in patients with long instrumentation and short arthrodesis, the time out of work time was 147.1 days (±56.6 SD, range 59–230). The average time out of work after the instrument removal surgery was 26.1 days (±9.5 SD, range 11–54).

Complications occurred in four patients. Two of them with a superficial infection (10.5%), which was successfully managed with oral antibiotics. These two patients corresponded to the group of long instrumentation and short arthrodesis. At the moment the instruments were removed, two patients presented a late fracture of one USS Schanz.

Discussion

Thoracolumbar fractures are caused by high-energy mechanisms, which generate different degrees of instability and vertebral injuries. Controversy still arises regarding the best treatment and the surgical indications of these fractures, specially when we deal with patients without neurological damage [3, 27, 43, 46, 47, 49, 52, 53]. However, the indirect reduction and transpedicular posterior instrumentation is often regarded as the best procedure, since it offers great advantages and less health costs, better quality of life in the rehabilitation process, and a faster social and work reintegration [1, 3, 15, 19, 34, 37, 38, 47, 52, 53].

Several studies of radiological follow-up showed some degree of loss in reduction and sagittal alignment achieved with posterior instrumentations [3, 15, 16, 19, 27, 36, 37, 38, 43, 47, 52, 53]. Due to its biomechanical characteristics, pedicular fixation maintains better reduction than the classic fixation and reduction in three points of the Harrington rods [1, 19, 32, 35, 37, 52, 53, 56]. Specifically, the USS internal fixator has proven to be an efficient system for reduction and maintenance of sagittal alignment [1, 34, 37, 52, 53]. There are variable reports of up to 50% of instrumental failure and early progression of kyphotic deformity [3, 16, 27, 36, 37, 47], many due to an insufficiency of anterior compression column not evaluated or underestimated. However, in this study, only two cases of Schanz fractures were observed not affecting the results. Just as the results reported by Sanderson et al.[46] and others, no proof of a statistically significant correlation between late clinical results (LBOS) and the evolution in time of radiological parameters was demonstrated.

Currently, the concept of saving mobile segments by limiting the number of segments included in the fusion has been incorporated as one of the fundamental principles of reconstructive surgery in spine trauma. In 1974, Armstrong and Johnston [4] introduced the concept of treating TLF with two Harrington rods in distraction without arthrodesis, expecting to remove the instrumentation once the fracture was consolidated. This would allow to recover some physiological mobility in the spinal segments included in the construction. Nevertheless, in the 1980’s, Jacobs et al. [25] introduced the concept of “Rod long, fuse short”, with three levels above and under the injury in order to limit the fusion only to the injured level; to maintain the biomechanical advantages in the reduction of a Harrington rod with a greater lever-arm, and in to recover mobility in non-fused segments when removing the instrumentation. There are different studies [2, 4, 10, 12, 20], in the 1990s that report a high incidence of mobility maintenance in segments that were transitorily stabilized with Harrington, using Jacob’s concepts, which in turn, offered good clinical results. In 20 patients with a non-fused Harrington instrumentation, Gardner and Armstrong [20] reported no spontaneous fusion or radiological evidence of arthrosis, with a high incidence of conserved articular space, which is then in 95% of the cases. 64% of the facets were considered to be normal, which was granted to a careful surgical dissection with no damage to the facets and to an early removal of the instrumentation. In 1993, Dekutoski et al. [10] reported an average mobility of 9° (60% normal range) in non-fused segments of the low lumbar spine, included in constructions with Harrington instruments. Akbarnia et al. [2] evaluated 88 non-fused and stabilized facets (44 levels) with dynamic radiological studies and oblique projections, finding that 43 segments presented physiological mobility and only two facets progressed into spontaneous fusion. Some reports state that the potential return to mobility of non-fused and stabilized vertebrae is highly controversial [6]. Kahanovitz et al. [26] reported histological changes in dog facets after stabilizations without fusion. In a study of residual mobility in dogs, Wood et al. [57] observed a considerable reduction of mobility and cicatrization of soft tissue after a later approach. Residual mobility can help IVDs to regenerate, since movement is essential for cartilage nutrition [24]. In 1993, Lindsey et al. [31] reported the presence of significant mobility in the non-fused segments (lower level of fracture) included in stabilizations with an internal fixator, and mobility comparable to the upper level of the instrumentation. However, this reveals that those segments with disc injury or with an endplate injury evolve to ankylosis, due to which the fusion of these segments is recommended.

In this study, we observed that 75% of the instrumented segments maintained a level of mobility considered normal or decreased, while 25% of the spinal levels were considered as non-mobile compared to normal segments at time of late follow up. However, only one of these was ankylosed. The evaluation of the case that evolved to ankylosis of the non-fused segment shows that there was a bad evaluation of the disc injury and of the involved endplate, since this patient was not eligible for a technique with economy of mobile segments. A considerable difference was found between the residual mobility of the non-fused segments when distinguishing mobility in non-fused bisegmentary instrumentations from mobility in non-fused segments with long instrumentations and short arthrodesis; 87.6% of mobile levels in the first group of patients respect to a 63.8% in patients with short arthrodesis. These figures are consistent with the ones presented by Müller et al. [38], who in 20 bisegmental instrumentations with monosegmental fusion of the transitorily stabilized segments, observed auto-fusion in 9 patients, a decreased mobility in 6 cases, and normal residual mobility in 5 patients, suggesting, just as Lindsey et al. [31], that if the lower segment is severely injured, it must be included in the fusion.

Recent studies with MRI have allowed the evaluation of the degree of injury of the traumatized IVD’s and their evolution through time [18, 41, 42, 45]. In a study with MRI of IVD’s adjacent to TLF, Oner et al. [41] observed different changes in morphology and intensity of post-traumatic discal sign, with a good intra- and inter-observer variability, stating that some disc types were associated to progressive kyphosis in patients treated in a conservative manner. On the other hand, in surgically managed patients, recurrent kyphosis was the result of disc sliding in the central depression of the vertebral plate, and not because of disc degeneration. Many of the IVD’s adjacent to the fracture stay biologically and morphologically intact [18, 41]. Correlation studies between MRI and anatomic sections of experimental fractures in corpses show that MRI is capable of detecting, in an early phase, macroscopic injuries in the IVD, which would justify the use of MRI to study the acute discal damage associated with TLF [42].

This study shows that there is a higher percentage of spinal segments with residual mobility (81.9%) in those IVD’s with a morphology considered as normal in the initial MRI. The evolution of these non-fused segments with respect to the intensity of the initial discal sign is variable and non-conclusive. In a follow-up study of 40 IVD’s adjacent to TLF, included in the instrumentations, Fürderer et al. [18] found 92% healthy discs after the removal of the disc instrumentation with morphology and intensity in post-instrumentation MRI. In the case of intact morphology, the intensity of disc signal may vary, but it has no influence in the morphologic course, due to which fusion is not recommended in these cases. In cases with evident morphological alterations and especially in combination with a severe or partial reduction of the disc signal intensity in T2, fusion would be relatively advisable.

ROM ranges were better in patients in whom the instrumentation was removed before 10 months of evolution, which agrees with the recommendation of Jacobs et al. [25] and Gardner & Armstrong [20] of removing the instrumentation after 6–9 month of evolution. Statistical correlation between residual ROM and late clinical results (LBOS) was not observed.

Conclusions

In the management of TLF, non-fused spinal segments included in pedicular instrumentation maintain mobility in a high percentage once the instrumentation is removed. 75% of the segments presented a normal or decreased ROM.

There exists a higher percentage of non-fused mobile segments when the instrumentation is removed before 10 months of evolution.

The MRI plays an important role in the surgical management of TLF. The IVD’s with normal morphology preserve their mobility in a high percentage once the instrumentation is removed, therefore fusion should not be considered in these cases. The intensity of the signal in the IVD’s is variable in TLF and has no prognostic value on the evolution of these segments and on persistence of mobility. There is no statistical correlation between the residual ROM degree and the late clinical results (LBOS).

References

- 1.Aebi M, Etter C, Thalgott J. Stabilization of the lower thoracic and lumbar spine with the internal spinal skeletal fixation system. Indications, technique and first results of treatment. Spine. 1987;12:544–551. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198707000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akbarnia BA, Crandall DG, Burkus K, Matthewa T. Use of long rods and a short arthrodesis for burst fractures of the thoracolumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76-A:1629–1635. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199411000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alanay A, Acaroglu E, Yazici M, Oznur A, Surat A. Short-segment pedicle intrumentation of thoracolumbar burst fractures. Does transpedicular intracorporeal grafting prevent early failure? Spine. 2001;26:213–217. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200101150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong GW, Johnston DH. Stabilization of spinal injuries using Harrington instrumentation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1974;56-B:590. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bastian L, Lange U, Knop C, Tusch G, Blauth M. Evaluation of the mobility of adjacent segments after posterior thoracolumbar fixation: a biomechanical study. Eur spine J. 2001;10:295–300. doi: 10.1007/s005860100278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behrens F, Kraft E, Oegema TR. Biochemical changes in articular cartilage after joint inmobilization by casting or external fixation. J Orthop Res. 1989;7:335–343. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100070305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boos N, Boesch C. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine. Potential for investigation of water content and biochemical composition. Spine. 1995;20:2358–2365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford DS, Mc Bride GG. Surgical management of thoracolumbar spine fractures with incomplete neurologic deficits. Clin Orthop relat Res. 1987;218:201–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniaux H. Transpedikulare reposition und spongiosaplastik bei wirbelbruchen der unteren burst-und lendenwirbelsaule. Unfallchirung. 1986;89:197–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dekutosky MB, Conlan ES, Salciccioli GG. Spinal mobility and deformity after Harrington rod stabilization and limited arthrodesis of thoracolumbar fractures. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75-A:168–175. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199302000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dick W. The “fixatuer interne” as a versatile implant for spine surgery. Spine. 1987;12:882–900. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198711000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodd CA, Fergusson CM, Pearcy MJ, Houghton GR. Vertebral motion measured using biplanar radiography before and after Harrington rod removal for unstable thoracolumbar fractures of the spine. Spine. 1986;11:452. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198606000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dvorak J, Panjabi M, Chang D, Theiler R, Grob D. Functional radiographic diagnosis of the lumbar spine. Flexion-extension and lateral bending. Spine. 1991;16:562–571. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199105000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehni G. The role of spine fusion. Question 9. Spine. 1987;6:308–310. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esses S, Bostford D, Kostuik J. Evaluation of surgical treatment for burst fractures. Spine. 1990;15:667–673. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199007000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esses S, Sachs B, Dreyzin V. Complications associated with the technique of pedicle screw fixation. A select survey of ABS members. Spine. 1993;18:2231–2239. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199311000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frankel H, Hancock D, Hyslop G. The value of postural reduction in the initial paraplegia and closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia and tetraplegia. Part 1. Paraplegia. 1969;7:179–192. doi: 10.1038/sc.1969.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fürderer S, Wenda K, Thiem N, Hachenberger R, Eysel P. Traumatic intervertebral disc lesion – magnetic resonance imaging as a criterion for or against intervertebral fusion. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:154–163. doi: 10.1007/s005860000238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaines R. Currents conceps review. The use of pedicle-screw internal fixation for the operative treatment of spinal disorders. J Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82-A:1458–1476. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200010000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gardner VO, Armstrong GW. Long-term lumbar facet joint changes in spinal fracture patients treated with Harrington rods. Spine. 1990;15:479. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199006000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gertzbein SD. Clasification of thoracic and lumbar fractures. Spine. 1994;19:626–628. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199403000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goel V, Gwon J, Chen J, Weinstein J, Lim T. Biomechanics of internal fixation system. Seminars in Spine Surg. 1992;4:128–135. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenough CG, Fraser RD. The effects of compensation on recovery from low back injury. Spine. 1989;14:947–955. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198909000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holm S, Nachemson A. Variations in the nutrition of the canine intervertebral disc induced by motion. Spine. 1983;8:866–874. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198311000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs R, Asher M, Snider R. Thoracolumbar spinal injuries. A comparative study of recumbent and operative treatment in 100 patients. Spine. 1980;5:463–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kahanovitz N, Arnoczky SP, Levine DB, Otis JP. The effects of internal fixation on the articular cartilage of unfused canine facet joint cartilage. Spine. 1984;9:268–272. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198404000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knop C, Fabian H, Bastian L, Blauth M. Late results of thoracolumbar fractures after posterior instrumentation and transpedicular bone grafting. Spine. 2001;26:88–99. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200101010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee CK. Accelerated degeneration of the segmental adyacent to a lumbar fusion. Spine. 1984;13:375–377. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198803000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee H, Kim H, Kim D, Suk K, Park J, Kim N. Reliability of magnetic resonance imaging in detecting posterior ligament complex injury in thoracolumbar spinal fractures. Spine. 2000;25:2079–2084. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200008150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leferinck VJ, Nijboer JM, Zimmerman KW, et al. Thoracolumbar spinal fractures: segmental range of motion after dorsal spondylodesis in 82 patients: a prospective study. Eur spine J. 2002;11:2–7. doi: 10.1007/s005860100331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindsey R, Dick W, Nunchuck S, Zach G. Residual intersegmental spinal mobility following limited pedicle fijation of thoracolumbar spine fractures with the fixateur interne. Spine. 1993;18:474–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magerl F. Stabilization of the lower thoracic and lumbar spine with external skeletal fixation. Clin Orthop. 1984;189:125–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magerl F, Aebi M, Gertzbein D, Harms J, Nazarian S. A comprehensive classification of thoracic and lumbar injuries. Eur Spine J. 1994;3:184–201. doi: 10.1007/BF02221591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marre B, Yurac R, Garcia R, Munjin M, Urzua A, Lecaros MA, Larraguibel F. Manejo de las lesiones disruptivas en la columna toracolumbar. Revista Chil Ortop y Trauma. 2002;43:130–139. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McAffe P, Werner F W, Mech M, Glisson R. A biomechanical analysis of spinal instrumentation systems in thoracolumbar fractures. Comparison of tradicional Harrington distraction instrumentation with segmental spinal instrumentation. Spine. 1985;10:204–217. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198504000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLain R, Sparling E, Benson D. Early failure of short-segment instrumentation for thoracolumbar fractures. A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75-A:162–167. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199302000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Munjin M, Yurac R, Marre B, Urzua A, Lecaros MA, Larraguibel F. Fracturas toracolumbares por mecanismo torsional (Tipo C):Resultados del tratamiento quirúrgico por vía posterior. Revista Chil Ortop y Trauma. 2002;43:55–68. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Müller U, Berlemann U, Sledge J, Schwarzenbach O. Treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures without neurologic deficit by indirect reduction and posterior instrumentation: bisegmental stabilization with monosegmental fusion. Eur spine J. 1999;8:284–289. doi: 10.1007/s005860050175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagata H, Schendel MJ, Transfeldt EE, Lewis JL. The effects of inmobilization of long segments of the spine on the adjacent and distal facet force and lumbosacral motion. Spine. 1993;18:2471–2479. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199312000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neumann P, Wang Y, Karrholm J, Malchau H, Nordwall A. Determination of inter-spinous procees distance in the lumbar spine. Eur Spine J. 1999;8:272–278. doi: 10.1007/s005860050172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oner F, Vander Rijt R, Ramos L, Dhert W, Verbout A. Changes in the disc space after fractures of the toracolumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80-B:833–839. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.80B5.8830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oner F, Vander Rijt R, Ramos L, Groen G, DherT W, Verbout A. Correlation of MR images of disc injuries with anatomic sections in experimental thoracolumbar spine fractures. Eur Spine J. 1999;8:194–198. doi: 10.1007/s005860050156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parker J, Lane J, Karaicovic E, Gaines R. Successful short-segment instrumentation and fusion for thoracolumbar spine fractures. A consecutive 4 1/2-years series. Spine. 2000;25:1157–1169. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200005010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearcy MJ, Burrough S. Assessment of bony union after interbody fusion of the lumbar spine using a biplanar radiographic technique. J Bone Joint Surg. 1982;64-B:228–232. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.64B2.7040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rudig L, Runkel M, Kreitner KF, Degreif J. Kernspintomographische untersuchung thorakolumbaler wiberfrakturen nach fixatuer-interne-stabilisierung. Unfallchirug. 1997;100:524–530. doi: 10.1007/s001130050152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanderson P, Fraser R, Hall D, Cain CM, Osti O, Potter G. Short segment fixation of thoracolumbar burst fractures without fusion. Eur Spine J. 1999;8:495–500. doi: 10.1007/s005860050212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen WJ, Liu TJ, Shen YS. Nonoperative treatment versus posterior fixation for thoracolumbar junction burst fractures without neurologic deficit. Spine. 2001;26:1038–1045. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200105010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shono Y, Kaneda K, AbumI K, Mc Afee, Cunningham B. Stability of posterior instrumentation and its effects on adjacent motion in the lumbosacral spine. Spine. 1998;23:1550–1558. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199807150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spivak JM, Vaccaro A, Cotler J. Thoracolumbar spine trauma: II. Principles of manegement. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:353–360. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199511000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanz SS. Motion of the lumbar spine: a roentgenologic study. AJR. 1953;69:399–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tertti M, Paajanen H, Laato M, Aho M, Komu M, Kormano M. Disc degeneration in magnetic resonance imaging. A comparative biochemical, histologic, and radiologic study in cadaver spines. Spine. 1990;16:629–634. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Urzua A. Manejo quirúrgico de las fracturas toracolumbares con USS. Rev Chilena Ortop y Traum. 1997;38:61–84. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Urzua A. Puesta al día: Fracturas toracolumbares. Rev Chilena Ortop y Traum. 1997;38:127–133. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Von Gumppenberg S, Vieweg J, Claudi J, Harms J. Die primäre versorgung der frischen verletzung von brust- und lendenwibersäule. Aktuel Traumatol. 1991;21:265–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whitesides T. Traumatic kyphosis of the thoracolumbar spine. Clin Orthop. 1977;128:78–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wiltse L. History of pedicle screw fixatión of the spine. Spine, State of art reviews. 1992;6:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wood, et al. Spine. 1992;17:1180–1186. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199210000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]